The Gillian Duffy affair, the start of this People’s Decade, was fascinating on many levels. Fundamentally, it revealed the schism in values and language that separated the elites from ordinary people. To the professional middle classes who by that point — after 13 years of New Labour government — had conquered the Labour Party, people like Mrs Duffy were virtually an alien species, and places like Rochdale were almost another planet. Indeed, one small but striking thing that happened in the Duffy / Brown fallout was a correction published in the Guardian. One of that newspaper’s initial reports on the Duffy affair had said that Rochdale was “a few hundred miles” from London. Readers wrote in to point out that it is only 170 miles from London. To the chattering classes, it was clear that Rochdale was as faraway and as foreign as Italy or Germany. More so, in fact.

The linguistic chasm between Duffy and Brown spoke volumes about Labour’s turn away from its traditional working-class base. Yes, there was the word “bigot”, but, strikingly, that wasn’t the word that most offended Mrs Duffy. No, she was most horrified by Brown’s description of her as “that woman”. “The thing that upset me was the way he said ‘that woman'”, she said. “I come from the north and when you say ‘that woman’, it’s really not very nice. Why couldn’t he have just said ‘that lady’?”

One reason Brown probably didn’t say “lady” is because in the starched, aloof, technocratic world New Labour inhabited, and helped to create, the word “lady” had all but been banned as archaic and offensive in the early 2000s. Since the millennium, various public-sector bodies had made moves to prevent people from saying lady to refer to a woman. One college advised against using the word lady, as it is “no longer appropriate in the new century”. An NHS Trust instructed its workers that “lady” is “not universally accepted” and should thus be avoided. In saying “that woman”, Brown was unquestionably being dismissive — “that piece of trash” is what he really meant — but he was also speaking in the clipped, watchful, PC tones of an elite that might have only been 170 miles from Rochdale (take note, Guardian) but which was in another world entirely in terms of values, outlook, culture and language.

“I’m not ‘that woman'”, said Duffy, and in many ways this became the rebellious cry of the People’s Decade. She was pushing back against the elite’s denigration of her. Against its denigration of her identity (as a lady), of her right to express herself publicly (“it’s just ridiculous”, as Brown said of that very public encounter), and most importantly of her concerns, in particular on the issue of immigration and its relationship to the welfare state.

The Brown-Duffy stand-off at the start of the People’s Decade exposed the colossal clash of values that existed between the new political oligarchy represented by Brown, Blair and other New Labour / New Conservative machine politicians and the working-class heartlands of the country. To Duffy and millions of other people, the relationship between welfare and nationhood was of critical importance. That is fundamentally what she collared Brown about. There are “too many people now who are not vulnerable but they can claim [welfare]”, she said, before asking about immigration. Her suggestion, her focus on the issue of health, education and welfare and the question of who has access to these things and why, was a statement about citizenship, and about the role of welfare as a benefit of citizenship. But to Brown, as to virtually the entire political class, it was just bigotry. Concern about community, nationhood and the impact of immigration is just xenophobic Little Englandism in the minds of the new elites. This was the key achievement of 13 years of New Labour’s censorious, technocratic and highly middle-class rule — the reduction of fealty to the nation to a species of bigotry.

Brendan O’Neill, “The People’s Decade”, Spiked, 2019-12-27.

March 21, 2025

QotD: Gordon Brown and the “Gillian Duffy affair”

March 15, 2025

QotD: Strategy

It has become popular of late to associate strategy with a “theory of victory”. Many policy pieces and journal articles define this as a narrative explanation of why a particular strategy will work — something every strategy must contain, if only implicitly. Others go so far as to insist that a strategy is nothing more than a theory of victory. […]

Strategy itself is a slippery term, used in slightly different ways in different contexts. In everyday usage, it is simply a plan to accomplish some task, whereas formal military definitions tend to specify the particular end. The US joint doctrinal definition, for instance, is: “A prudent idea or set of ideas for employing the instruments of national power in a synchronized and integrated fashion to achieve theater, national, and/or multinational objectives”. If strategy is not quite a theory for victory, the connection between them is apparent.

There is a subtle problem with this definition, however. Victories are rarely won in precisely the way the victors anticipate. Few commanders can call their own shots, as Napoleon did in Italy or William Slim in Burma. Wars are complex and messy things, and good strategy requires constant adaptation to circumstance — a system of expedients, as Moltke put it. Even with the benefit of hindsight, the cause of a war’s outcome is not always perfectly clear, as the ongoing debate over strategic bombing bears witness.

Indeed, the very idea that strategy represents a plan is very recent. From the first adoption of the word into modern languages,1 strategy was defined more as an art: of “commanding and of skilfully employing the means [the commander] has available”, of “campaigning”, of “effectively directing masses in the theater of war”. The emphasis was decidedly on execution, not planning. As recently as 2001, the US Army’s FM 3-0 Operations defined strategy as: “the art and science of developing and employing armed forces and other instruments of national power in a synchronized fashion to secure national or multinational objectives”. Something one does, not something one thinks.

This is best understood by analogy to tactics, a realm less given to formalism and abstraction. What makes a good tactician? Devising a good plan is certainly part of it, but most tactical concepts are not especially unique — there are only so many tools in the tactical toolkit. The real challenge lies in execution: providing for comms and logistics, ensuring subordinates understand the plan, going through rehearsals, making sure that everyone is doing their job correctly, then putting oneself at the point where things are likely to go wrong and dealing with the unexpected.

Ben Duval, “Is Strategy Just a Theory of Victory? Notes on an Annoying Buzzword”, The Bazaar of War, 2024-12-01.

1. This was before Clausewitz’s inadvertent redefinition of strategy, when the term still referred to what we now call “operational art”.

February 28, 2025

Everyday Life in the Roman Empire – An Empire of Peoples

seangabb

Published 28 Aug 2024The Roman Empire had a geographical logic, but was an endlessly diverse patchwork of linguistic, ethnic and religious groups. In this lecture, Sean Gabb describes the diversity:

Geographical Logic – 00:00:00

Linguistic Diversity – 00:06:57

Italy – 00:12:46

Greece – 00:17:23

Greeks and Romans – 00:21:01

Egypt – 00:28:24

Greeks, Romans, Egyptians – 00:33:00

North Africa – 00:37:27

The Jews – 00:41:20

Greeks, Romans, Jews – 00:44:10

Gaul – 00:50:36

Britain – 00:52:26

Greeks, Romans, Britons – 00:54:58

The East – 00:59:22

Bibliography – 01:01:20

(more…)

January 16, 2025

QotD: “At promise” youth

A new law in California bans the use, in official documents, of the term “at risk” to describe youth identified by social workers, teachers, or the courts as likely to drop out of school, join a gang, or go to jail. Los Angeles assemblyman Reginald B. Jones-Sawyer, who sponsored the legislation, explained that “words matter”. By designating children as “at risk”, he says, “we automatically put them in the school-to-prison pipeline. Many of them, when labeled that, are not able to exceed above that.”

The idea that the term “at risk” assigns outcomes, rather than describes unfortunate possibilities, grants social workers deterministic authority most would be surprised to learn they possess. Contrary to Jones-Sawyer’s characterization of “at risk” as consigning kids to roles as outcasts or losers, the term originated in the 1980s as a less harsh and stigmatizing substitute for “juvenile delinquent”, to describe vulnerable children who seemed to be on the wrong path. The idea of young people at “risk” of social failure buttressed the idea that government services and support could ameliorate or hedge these risks.

Instead of calling vulnerable kids “at risk”, says Jones-Sawyer, “we’re going to call them ‘at-promise’ because they’re the promise of the future”. The replacement term — the only expression now legally permitted in California education and penal codes — has no independent meaning in English. Usually we call people about whom we’re hopeful “promising”. The language of the statute is contradictory and garbled, too. “For purposes of this article, ‘at-promise pupil’ means a pupil enrolled in high school who is at risk of dropping out of school, as indicated by at least three of the following criteria: Past record of irregular attendance … Past record of underachievement … Past record of low motivation or a disinterest in the regular school program.” In other words, “at-promise” kids are underachievers with little interest in school, who are “at risk of dropping out”. Without casting these kids as lost causes, in what sense are they “at promise”, and to what extent does designating them as “at risk” make them so?

This abuse of language is Orwellian in the truest sense, in that it seeks to alter words in order to bring about change that lies beyond the scope of nomenclature. Jones-Sawyer says that the term “at risk” is what places youth in the “school-to-prison pipeline”, as if deviance from norms and failure to thrive in school are contingent on social-service terminology. The logic is backward and obviously naive: if all it took to reform society were new names for things, then we would all be living in utopia.

Seth Barron, “Orwellian Word Games”, City Journal, 2020-02-19.

January 3, 2025

QotD: Whimsy

Whimsy is an aesthetic category for cultural artifacts that do not quite conform to, but do not fully violate, the rules of contemporary culture. Whimsy is licensed departure. It makes free with cultural conventions in a way we find charming, funny, winsome and sometimes freeing. Whimsy is chaos on a leash, departure that may not stray.

Grant McCracken, “Discontinuous innovation and the mysteries of Roger Ebert”, This Blog Sits at the, 2005-08-03.

December 17, 2024

October 17, 2024

QotD: Soldiers and warriors

We want to start with asking what the distinction is between soldiers and warriors. It is a tricky question and even the U.S. Army sometimes gets it badly wrong ([author Steven] Pressfield, I should note, draws a distinction which isn’t entirely wrong but is so wrapped up with his dodgy effort to use discredited psychology that I think it is best to start from scratch). We have a sense that while both of these words mean “combatant”, that they are not quite equivalent.

[…]

But why? The etymologies of the words can actually help push us a bit in the right direction. Warrior has a fairly obvious etymology, being related to war (itself a derivative of French guerre); as guerre becomes war, so Old French guerreieor became Middle English werreior and because that is obnoxious to say, modern English “warrior” (which is why it is warrior and not “warrer” as we might expect if it was regularly constructed). By contrast, soldier comes – it has a tortured journey which I am simplifying – from the sold/sould French root meaning “pay” which in turn comes from Latin solidus, a standard Late Roman coin. So there is clearly something about pay, or the lack of pay involved in this distinction, but clearly it isn’t just pay or the word mercenary would suit just as well.

So here is the difference: a warrior is an individual who wars, because it is their foundational vocation, an irremovable part of their identity and social position, pursued for those private ends (status, wealth, place in society). So the core of what it is to be a warrior is that it is an element of personal identity and also fundamentally individualistic (in motivation, to be clear, not in fighting style – many warriors fought with collective tactics, although I think it fair to say that operation in units is much more central to soldiering than the role of a warrior, who may well fight alone). A warrior remains a warrior when the war ends. A warrior remains a warrior whether fighting alone or for themselves.

By contrast, a soldier is an individual who soldiers (notably a different verb, which includes a sense of drudgery in war-related jobs that aren’t warring per se) as a job which they may one day leave behind, under the authority of and pursued for a larger community which directs their actions, typically through a system of regular discipline. So the core of what it is to be a soldier is that it is a not-necessarily-permanent employment and fundamentally about being both in and in service to a group. A soldier, when the war or their term of service ends, becomes a civilian (something a warrior generally does not do!). A soldier without a community stops being a soldier and starts being a mercenary.

Incidentally, this distinction is not unique to English. Speaking of the two languages I have the most experience in, both Greek and Latin have this distinction. Greek has machetes (μαχητής, lit: “battler”, a mache being a battle) and polemistes (πολεμιστής, lit: “warrior”, a polemos being a war); both are more common in poetry than prose, often used to describe mythical heroes. Interestingly the word for an individual that fights out of battle order (when there is a battle order) is a promachos (πρόμαχος, lit: “fore-fighter”), a frequent word in Homer. But the standard Greek soldier wasn’t generally called any of these things, he was either a hoplite (ὁπλίτης, “full-equipped man”, named after his equipment) or more generally a stratiotes (στρατιώτης, lit: “army-man” but properly “soldier”). That general word, stratiotes is striking, but its root is stratos (στρατός, “army”); a stratiotes, a soldier, for the ancient Greeks was defined by his membership in that larger unit, the army. One could be a machetes or a polemistes alone, but only a stratiotes in an army (stratos), commanded, presumably, by a general (strategos) in service to a community.

Latin has the same division, with similar shades of meaning. Latin has bellator (“warrior”) from bellum (“war”), but Roman soldiers are not generally bellatores (except in a poetic sense and even then only rarely), even when they are actively waging war. Instead, the soldiers of Rome are milites (sing. miles). The word is related to the Latin mille (“thousand”) from the root “mil-” which indicates a collection or combination of things. Milites are thus – like stratiotes, men put together, defined by their collective action for the community (strikingly, groups acting for individual aims in Latin are not milites but latrones, bandits – a word Roman authors also use very freely for enemy irregular fighters, much like the pejorative use of “terrorist” and “insurgent” today) Likewise, the word for groups of armed private citizens unauthorized by the state is not “militia”, but “gang”. The repeated misuse by journalists of “militia” which ought only refer to citizens-in-arms under recognized authority, drives me to madness).

(I actually think these Greek and Latin words are important for understanding the modern use of “warrior” and “soldier” even though they don’t give us either. Post-industrial militaries – of the sort most countries have – are patterned on the modern European military model, which in turn has its foundations in the Early Modern period which in turn (again) was heavily influenced by how thinkers of that period understood Greek and Roman antiquity (which was a core part of their education; this is not to say they were always good at understanding classical antiquity, mind). Consequently, the Greek and Roman understanding of the distinction probably has significant influence on our understanding, though I also suspect that we’d find distinctions in many languages along much the same lines.)

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: The Universal Warrior, Part I: Soldiers, Warriors, and …”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2021-01-29.

August 22, 2024

“Say my pronouns, peasant!”

Andrew Doyle doubts that the push for bespoke personal pronouns will have any lasting impact on the language and how it is used despite all the political capital invested to coerce people to adopt them:

For all the demands of activists that “they” and “them” should be normalised as singular pronouns, very few members of the public have adapted their speech patterns accordingly. Even when the print media started following this odd new craze after Sam Smith declared himself to be “non-binary” in September 2019, the trend simply didn’t catch on.

This is hardly surprising. For one thing, most of the articles that adhere to this creed end up being both syntactically and stylistically incoherent. Take the following excerpt from a review of Judith Butler’s latest book in The Atlantic:

In essence, Butler accuses gender-crits of “phantasmatic” anxieties. They dismiss, with that invocation of a “phantasm”, apprehension about the presence of trans women in women’s single-sex spaces…

At first glance, “they” could appear to be referring to the “gender-crits”, but in this case it refers to Butler. A reader unfamiliar with the subject will inevitably find this confusing. Throughout the article, one is forced to reset one’s reading instincts – cultivated through a lifetime of universally-shared linguistic conventions – and even though the meaning eventually becomes clear, the prose is irredeemably maladroit. In other words, those who accept these new rules must first surrender their capacity to write well.

Of course, we all know that “they” is commonly used in the singular sense in cases of unknown identity. So we might say “Someone has left their car keys here” because we cannot be sure of the sex of the stranger in question. This causes no confusion at all because the sentence automatically conveys the uncertainty. Such colloquial exceptions aside, “they” is simply not used as a singular pronoun among the general population.

While identitarian activists love to dismiss Shakespeare as an irrelevant dead white male, they are happy to invoke him to support their attempts to impose their own modifications to the English language. In almost all articles on the singular “they”, one will find a reference somewhere to Shakespeare. “For decades, transgender rights advocates have noted that literary giants Emily Dickinson, William Shakespeare, William Wordsworth, and Geoffrey Chaucer all used singular they in their writing”, states one writer. “Shakespeare used the singular they, and so should you”, claims another. In the Washington Post, a professor of English writes that “Shakespeare and Austen both used singular “they” … just as many English speakers do now”.

It’s difficult to see how this argument is in any way compelling. Nobody is claiming that language does not evolve. The point is rather that the singular “they” has not caught on in modern usage, in spite of activists’ demands that it should. Are gender identity ideologues really urging us to adopt sixteenth-century language in the name of progress? I have yet to see any of them favouring “thou” as a familiar form of address. They tend to prefer “y’all”, and if this was ever used by Shakespeare I must have missed it.

July 29, 2024

W.H. Smith attempts to rebrand their stores to “raise awareness” or something

British bookseller from time immemorial, W.H. Smith, apparently decided that the corporate branding they’d been using since the 18th century was just too boring for modern consumers, so they brainstormed a daring new design for the 21st century … that sucked.

“UK High Street” from https://www.whsmithplc.co.uk/media/media-gallery/images

When the British retailer, W.H. Smith, rebranded its logo last year, confusion and bafflement ensued.

The high street fixture, its Times New Roman logo mostly unchanged since 1792, earned its reputation by selling books, stationery, and for fleecing bleary-eyed travellers in airports. Through sheer zombie persistence, W.H. Smith remains a constant of British retail. Never mind the threadbare carpets, the general dilapidation, or the desperate staff forced to offer you a bottle of knock-off perfume with your twenty Lambert and Butler.

W.H. Smith endures because its business model concentrates on a captive audience. Go to an airport or a hospital — any place in which people cannot escape — and you’ll find a W.H. Smith reliably charging double for a Lucozade Sport. W.H. Smith will outlive Great Britain. The retailer’s existence — puzzling to the most scientific of minds — defies natural law.

Last year, creative designers attempted to play God. They sanded off the logo’s regnant edges and stripped “Smiths” altogether. The dynamic branding screamed minimalism: a plain, white “WHS” stamped on to a blue background.

I’d imagine the big revelation underwhelmed those paying for the work. “That’s interesting.” Or “It’s certainly different“.

Mockery ensued. “Baffling” said one. “It looks like the NHS logo,” observed another.

No doubt the designers plotted a revolution in design. Of course, these “creatives” — invariably young and invariably uncreative — fancied their vandalism as “forward thinking” and “dynamic”. I’ll wager at least one thought the new logo addressed the plight of some faraway progressive cause to which they subscribe. The public, unschooled in the most voguish developments in design, concluded: The new logo is shit.

W.H. Smith soon backtracked. Passive-aggressive defences of the staid new logo melted into sulky denial. It’s just a trial, they mewled.

A breathless spokesman revealed the truth. Or some addled version of the truth. The fresh signs, they revealed, were “designed to raise awareness of the products W.H. Smith sells”. What else, I wonder, is a shop sign meant to achieve?

The phrase “raising awareness” is one of a litany of linguistic evasions which say nothing. By shoehorning that ghastly phrase into a sentence, the speaker hopes to evade criticism. Reader, I’m not ploughing through a duty-free bottle of Chateau le Peuy Saincrit in the obscene Bulgarian sunshine. I’m raising awareness of the plight of southern French winemakers.

That passive-aggressive statement of the obvious — our shop sign raises awareness of our shop — you plebeian fools — crystallises the creative industry’s age problem.

Three-quarters of the creative industry is under 45. Perhaps this age gap (not the sexually consensual and fun kind) explains why so much of what we see and hear is cliché-riddled evasive hoo-hah.

When talking to anyone under 45, I mentally add a question mark to the end of their sentence. Millennials and Zoomers avoid declarative sentences. Listen. Almost every utterance sounds like a question. Further to this quirk, I note the adverbs and filler words. Young people stuff their speech with “basically”, “actually”, “literally”, and “like”. Zoomers are especially militant. They eschew capital letters. Capital letters are grammatical fascism. Full stops reveal a latent proclivity for Zyklon-B. Influencers add another tic to this repertoire of anxiety and unsurety. They crackle their voice as if a frog has lodged in their throat.

July 20, 2024

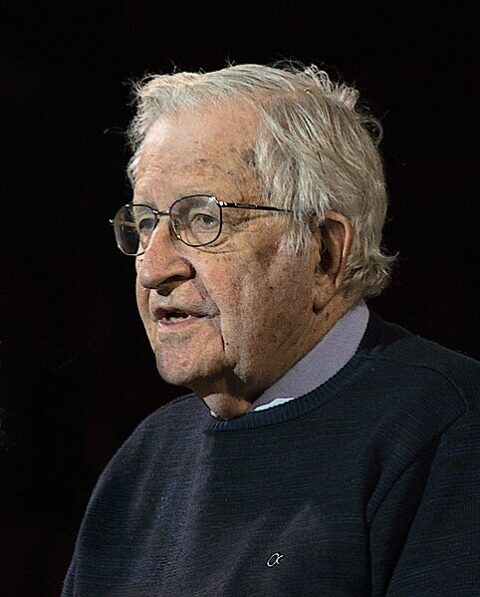

Counting citation numbers in “Chomskys”

The latest anonymous reviewer in Astral Codex Ten‘s “Your Book Review” series considers the work of Noam Chomsky, and notes just how his works dominate the field of linguistics:

Noam Chomsky speaks about humanity’s prospects for survival in Amherst, Massachusetts, United States on 13 April 2017.

Original photo by Σ, retouched by Wugapodes via Wikimedia Commons.

You may have heard of a field known as “linguistics”. Linguistics is supposedly the “scientific study of language“, but this is completely wrong. To borrow a phrase from elsewhere, linguists are those who believe Noam Chomsky is the rightful caliph. Linguistics is what linguists study.

I’m only half-joking, because Chomsky’s impact on the study of language is hard to overstate. Consider the number of times his books and papers have been cited, a crude measure of influence that we can use to get a sense of this. At the current time, his Google Scholar page says he’s been cited over 500,000 times. That’s a lot.

It isn’t atypical for a hard-working professor at a top-ranked institution to, after a career’s worth of work and many people helping them do research and write papers, have maybe 20,000 citations (= 0.04 Chomskys). Generational talents do better, but usually not by more than a factor of 5 or so. Consider a few more citation counts:

- Computer scientist Alan Turing (65,000 = 0.13 Chomskys)

- Neuro / cogsci / AI researcher Matthew Botvinick (83,000 = 0.17 Chomskys)

- Mathematician Terence Tao (96,000 = 0.19 Chomskys)

- Cognitive scientist Joshua Tenenbaum (107,000 = 0.21 Chomskys)

- Nobel-Prize-winning physicist Richard Feynman (120,000 = 0.24 Chomskys)

- Psychologist and linguist Steven Pinker (123,000 = 0.25 Chomskys)

- Two-time Nobel Prize winner Linus Pauling (128,000 = 0.26 Chomskys)

- Neuroscientist Karl Deisseroth (143,000 = 0.29 Chomskys)

- Biologist Charles Darwin (182,000 = 0.36 Chomskys)

- Theoretical physicist Ed Witten (250,000 = 0.50 Chomskys)

- AI researcher Yann LeCun (352,000 = 0.70 Chomskys)

- Historian and philosopher Hannah Arendt (359,000 = 0.72 Chomskys)

- Karl Marx (458,000 = 0.92 Chomskys)

Yes, fields vary in ways that make these comparisons not necessarily fair: fields have different numbers of people, citation practices vary, and so on. There is also probably a considerable recency bias; for example, most biologists don’t cite Darwin every time they write a paper whose content relates to evolution. But 500,000 is still a mind-bogglingly huge number.

Not many academics do better than Chomsky citation-wise. But there are a few, and you can probably guess why:

- Human-Genome-Project-associated scientist Eric Lander (685,000 = 1.37 Chomskys)

- AI researcher Yoshua Bengio (780,000 = 1.56 Chomskys)

- AI researcher Geoff Hinton (800,000 = 1.60 Chomskys)

- Philosopher and historian Michel Foucault (1,361,000 = 2.72 Chomskys)

…well, okay, maybe I don’t entirely get Foucault’s number. Every humanities person must have an altar of him by their bedside or something.

Chomsky has been called “arguably the most important intellectual alive today” in a New York Times review of one of his books, and was voted the world’s top public intellectual in a 2005 poll. He’s the kind of guy that gets long and gushing introductions before his talks (this one is nearly twenty minutes long). All of this is just to say: he’s kind of a big deal.

[…]

Since around 1957, Chomsky has dominated linguistics. And this matters because he is kind of a contrarian with weird ideas.

July 18, 2024

QotD: Culture in the late western Roman Empire

This vision of the collapse of Roman political authority in the West may seem a bit strange to readers who grew up on the popular narrative which still imagines the “Fall of Rome” as a great tide of “barbarians” sweeping over the empire destroying everything in their wake. It’s a vision that remains dominant in popular culture (indulged, for instance, in games like Total War: Attila; we’ve already talked about how strategy games in particular tend to embrace this a-historical annihilation-and-replacement model of conquest). But actually culture is one of the areas where the “change and continuity” crowd have their strongest arguments: finding evidence for continuity in late Roman culture into the early Middle Ages is almost trivially easy. The collapse of Roman authority did not mark a clean cultural break from the past, but rather another stage in a process of cultural fusion and assimilation which had been in process for some time.

The first thing to remember, as we’ve already discussed, is that the population of the Roman Empire itself was hardly uniform. Rather the Roman empire as it violently expanded, had absorbed numerous peoples – Celtiberians, Iberians, Greeks, Gauls, Syrians, Egyptians, and on and on. Centuries of subsequent Roman rule had led to a process of cultural fusion, whereby those people began to think of themselves as Romani – Romans – as they both adopted previously Roman cultural elements and their Roman counterparts adopted provincial culture elements (like trousers!).

In particular, by the fifth century, the majority of these self-described Romani, including the overwhelming majority of elites, had already adopted a provincial religion: Christianity, which had in turn become the Roman religion and a core marker of Roman identity by the fifth century. Indeed, the word paganus, increasingly used in this period to refer to the remaining non-Christian population, had a root-meaning of something like “country bumpkin”, reflecting the degree to which for Roman elites and indeed many non-elites, the last fading vestiges of the old Greek and Roman religions were seen as out of touch. Of course Christianity itself came from the fringes of the Empire – a strange mystery cult from the troubled frontier province of Judaea in the Levant which had slowly grown until it had become the dominant religion of the empire, receiving official imperial favor and preference.

The arrival of the “barbarians” didn’t wipe away that fusion culture. With the exception of the Angles, Saxons and Jutes who eventually ended up in England, the new-comers almost uniformly learned the language of the Roman west – Latin – such that their descendants living in those lands, in a sense still speak it, in its modern forms: Spanish, French, Italian, Portuguese, etc. alongside more than a dozen local regional dialects. All are derived from Latin (and not, one might note, from the Germanic languages that the Goths, Vandals, Franks and so on would have been speaking when they crossed the Roman frontier).

They also adopted the Roman religion, Christianity. I suspect sometimes the popular imagination – especially the one that comes with those extraordinarily dumb “Christian dark age” graphs – is that when the “barbarians invade” the Romans were still chilling in their Greco-Roman temples, which the “barbarians” burned down. But quite to the contrary – the Romans were the ones shutting down the old pagan temples at the behest of the now Christian Roman emperors, who busied themselves building beautiful and marvelous churches (a point The Bright Ages makes very well in its first chapter).

The “barbarians” didn’t tear down those churches – they built more of them. There was some conflict here – many of the Germanic peoples who moved into the Roman Empire had been converted to Christianity before they did so (again, the Angles and Saxons are the exception here, converting after arrival), but many of them had been converted through a bishop, Ulfilias, from Constantinople who held to a branch of Christian belief called “Arianism” which was regarded as heretical by the Roman authorities. The “barbarians” were thus, at least initially, the wrong sort of Christian and this did cause friction in the fifth century, but by the end of the sixth century nearly all of these new kingdoms created in the wake of the collapse of Roman authority were not only Christian, but had converted to the officially accepted Roman “Chalcedonian” Christianity. We’ll come back later to the idea of the Church as an institution, but for now as a cultural marker, it was adopted by the “barbarians” with aplomb.

Artwork also sees the clear impact of cultural fusion. Often this transition is, I think, misunderstood by students whose knowledge of artwork essentially “skips” Late Antiquity, instead jumping directly from the veristic Roman artwork of the late republic and the idealizing artwork of the early empire directly to the heavily stylized artwork of Carolingian period and leads some to conclude that the fall of Rome made the artists “bad”. There are two problems: the decline here isn’t in quality and moreover the change didn’t happen with the fall of the Roman Empire but quite a bit earlier. […]

Late Roman artwork shows a clear shift into stylization, the representation of objects in a simplified, conventional way. You are likely familiar with many modern, highly developed stylized art forms; the example I use with my students is anime. Anime makes no effort at direct realism – the lines and shading of characters are intentionally simplified, but also bodies are intentionally drawn at the wrong proportions, with oversized faces and eyes and sometimes exaggerated facial expressions. That doesn’t mean it is bad art – all of that stylization is purposeful and requires considerable skill – the large faces, simple lines and big expressions allow animated characters to convey more emotion (at a minimum of animation budget).

Late Roman artwork moves the same way, shifting from efforts to portray individuals as real-to-life as possible (to the point where one can recognize early emperors by their facial features in sculpture, a task I had to be able to perform in some of my art-and-archaeology graduate courses) to efforts to portray an idealized version of a figure. No longer a specific emperor – though some identifying features might remain – but the idea of an emperor. Imperial bearing rendered into a person. That trend towards stylization continues into religious art in the early Middle Ages for the same reason: the figures – Jesus, Mary, saints, and so on – represent ideas as much as they do actual people and so they are drawn in a stylized way to serve as the pure expressions of their idealized nature. Not a person, but holiness, sainthood, charity, and so on.

And it really only takes a casual glance at the artwork I’ve been sprinkling through this section to see how early medieval artwork, even out through the Carolingians (c. 800 AD) owes a lot to late Roman artwork, but also builds on that artwork, particularly by bringing in artistic themes that seem to come from the new arrivals – the decorative twisting patterns and scroll-work which often display the considerable technical skill of an artist (seriously, try drawing some of that free-hand and you suddenly realize that graceful flowing lines in clear symmetrical patterns are actually really hard to render well).

All of the cultural fusion was effectively unavoidable. While we can’t know their population with any certainty, the “barbarians” migrating into the faltering western Empire who would eventually make up the ruling class of the new kingdoms emerging from its collapse seem fairly clearly to have been minorities in the lands they settled into (with the notable exception, again, of the Angles, Saxons and Jutes – as we’re going to see this pattern again and again, Britain has an unusual and rather more traumatic path through this period than much of the rest of Roman Europe). They were, to a significant degree, as Guy Halsall (op. cit.) notes, melting into a sea of Gallo-Romans, or Italo-Romans, or Ibero-Romans.

Even Bryan Ward-Perkins, one of the most vociferous members of the decline-and-fall camp, in his explosively titled The Fall of Rome and the End of Civilization (2005) – this is a book whose arguments we will come back to in some detail – is forced to concede that “even in Britain the incomers [sic] had not dispossessed everyone” of their land, but rather “the invaders entered the empire in groups that were small enough to leave plenty to share with the locals” (66-7). No vast replacement wave this, instead the new and old ended up side by side. Indeed, Odoacer, seizing control of Italy in 476, we are told, redistributed a third of the land; it’s unclear if this meant the land itself or the tax revenue on it, but in either case clearly the majority of the land remained in the hands of the locals which, by this point in the development of the Roman countryside, will have mostly meant in the hands of the local aristocracy.

Instead, as Ralph Mathisen documents in Roman aristocrats in barbarian Gaul: strategies for survival in an age of transition (1993), most of the old Roman aristocracy seems to have adapted to their changing rulers. As we’ll discuss next week, the vibrant local government of the early Roman empire had already substantially atrophied before the “barbarians” had even arrived, so for local notables who were rich but nevertheless lived below the sort of mega-wealth that could make one a player on the imperial stage, little real voice in government was lost when they traded a distant, unaccountable imperial government for a close-by, unaccountable “barbarian” one. Instead, as Mathisen notes, some of the Gallo-Roman elite retreat into their books and estates, while more are co-opted into the administration of these new breakaway kingdoms, who after all need literate administrators beyond what the “barbarians” can provide. Mathisen notes that in other cases, Gallo-Roman aristocrats with ambitions simply transferred those ambitions from the older imperial hierarchy to the newer ecclesiastical one; we’ll talk more about the church as an institution next week. Distinct in the fifth century, by the end of the sixth century in Gaul, the two aristocracies: the barbarian warrior-aristocracy and the Gallo-Roman civic aristocracy had melded into one, intermarried and sharing the same religion, values and culture.

In this sense there really is a very strong argument to be made that the “Romans” and indeed Roman culture never left Rome’s lost western provinces – the collapse of the political order did not bring with it the collapse of the Roman linguistic or cultural sphere, even if it did fragment it.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Rome: Decline and Fall? Part I: Words”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2022-01-14.

July 17, 2024

QotD: “Orwellian”

All writers enjoying respect and popularity in their lifetimes entertain the hope that their work will outlive them. The true mark of a writer’s enduring influence is the adjectification of his (sorry, but it usually is “his”) name. An especially jolly Christmas scene is said to be “Dickensian”. A cryptically written story is “Hemingwayesque”. A corrupted legal process gives rise to a “Kafkaesque” nightmare for the falsely accused. A ruthless politician takes a “Machiavellian” approach to besting his rival.

But the greatest of these is “Orwellian”. This is a modifier that The New York Times has declared “the most widely used adjective derived from the name of a modern writer … It’s more common than ‘Kafkaesque’, ‘Hemingwayesque’ and ‘Dickensian’ put together. It even noses out the rival political reproach ‘Machiavellian’, which had a 500-year head start.”

Orwell changed the way we think about the world. For most of us, the word Orwellian is synonymous with either totalitarianism itself or the mindset that is eager to employ totalitarian methods — notably the bowdlerization or suppression of speech and freedoms — as a hedge against popular challenge to a politically correct vision of society dictated by a small cadre of elites.

Indeed, it was thanks to Orwell’s books — forbidden, acquired by stealth and owned at peril — that many freedom fighters suffering under repressive regimes, found the inspiration to carry on their struggle. In his memoir, Adiós Havana, for example, Cuban dissident Andrew J. Memoir wrote, “Books such as … George Orwell’s Animal Farm and 1984 became clandestine bestsellers, for they depicted in minute detail the communist methodology of taking over a nation. These […] books did more to open the eyes of the blind, including mine, than any other form of expression.”

Barbara Kay, “The way they teach Orwell in Canada is Orwellian”, The Post Millennial, 2019-11-29.

June 18, 2024

QotD: The peoples incorporated or “allied” to Rome in the Republic’s Italian expansion

In one way, pre-Roman Italy was quite a lot like Greece: it consisted of a bunch of independent urban communities situated on the decent farming land (that is the lowlands), with a number of less-urban tribal polities stretching over the less-farming-friendly uplands. While pre-Roman urban communities weren’t exactly like the Greek polis, they were fairly similar. Greek colonization beginning in the eighth century added actual Greek poleis to the Italian mix and frankly they fit in just fine. On the flip side, there were the Samnites, a confederation of tribal communities with some smaller towns occupying mostly rough uplands not all that dissimilar to the Greek Aetolians, a confederation of tribal communities and smaller towns occupying mostly rough uplands.

In one very important way, pre-Roman Italy was very much not like Greece: whereas in Greece all of those communities shared a single language, religion and broad cultural context, Roman Italy was a much more culturally complex place. Consequently, as the Romans slowly absorbed pre-Roman Italy into the Roman Italy of the Republic, that meant managing the truly wild variety of different peoples in their alliance system. Let’s quickly go through them all, moving from North to South.

The Romans called the region south of the Alps but north of the Rubicon River Cisalpine Gaul and while we think of it as part of Italy, the Romans did not. That said, Gallic peoples had pushed into Italy before and a branch of the Senones occupied the lands between Ariminum and Ancona. Although Gallic peoples were always a factor in Italy, the Romans don’t seem to have incorporated their communities as socii; indeed the Romans were generally at their most ruthless when it came to interactions with Gallic peoples (despite the tendency to locate the “unassimilable” people on the Eastern edge of Rome’s empire, it was in fact the Gauls that the Romans most often considered in this way, though as we will see, wrongly so). That’s not to say that there was no cultural contact, of course; the Romans ended up adopting almost all of the Gallic military equipment set, for instance. In any event, it wouldn’t be until the late first century BCE that Cisalpine Gaul was merged into Italy proper, so we won’t deal too much with the Gauls just yet. I do want to note that, when we are thinking about the diversity of the place, even to speak of “the Gauls” is to be terribly reductive, as we are really thinking of at least half a dozen different Gallic peoples (Senones, Boii, Inubres, Lingones, etc) along with the Ligures and the Veneti, who may have been blends of Gallic and Italic peoples (though we are more poorly informed about both than we’d like).

Moving south then, we first meet the Etruscans, who we’ve already discussed, their communities – independent cities joined together in defensive confederations before being converted into allies of the Romans – clustered on north-western coast of Italy. They had a language entirely unrelated to Latin – or indeed, any other known language – and their own unique religion and culture. The Romans adopted some portions of that culture (in particular the religious practices) but the Etruscans remained distinct well into the first century. While a number of Etruscan communities backed the Samnites in the Third Samnite War (298-290 BC) culminating in the Battle of Sentinum (295) as a last-ditch effort to prevent Roman hegemony over the peninsula, the Etruscans subsequently remained quite loyal to Rome, holding with the Romans in both the Second Punic and Social Wars. It is important to keep in mind that while we tend to talk about “the Etruscans” (as the Romans sometimes do) they would have thought of themselves first through their civic identity, as Perusines, Clusians, Populinians and so on (much like their Greek contemporaries).

Moving further south, we have the peoples of the Apennines (the mountain range that cuts down the center of Italy). The people of the northern Apennines were the Umbri (that is, Umbrian speakers), though this linguistic classification hides further cultural and political differences. We’ve met the Sabines – one such group, but there were also the Volsci and Marsi (the latter particularly well known for being hard fighters as allies to Rome; Appian reports that the Marsi had a saying prior to the Social War, “No Triumph against the Marsi nor without the Marsi”). Further south along the Apennines were the Oscan speakers, most notably the Samnites (who resisted the Romans most strongly) but also the Lucanians and Paelignians (the latter also get a reputation for being hard fighters, particularly in Livy). The Umbrian and Oscan language families are related (though about as different from each other as Italian from Spanish; they and Latin are not generally mutually intelligible) and there does seem to have been some cultural commonality between these two large groups, but also a lot of differences. Their religion included a number of practices and gods unknown to the Romans, some later adopted (Oscan Flosa adapted as Latin Flora, goddess of flowers) and some not (e.g. the “Sacred Spring” rite, Strabo 5.4.12).

Also Oscan speakers, the Campanians settled in Campania (surprise!) at some early point (perhaps around 1000-900 BC) and by the fifth century were living in urban communities politically more similar to Latium and Etruria (or Greece, which will make sense in a moment) than their fellow Oscan speakers in the hills above, to the point that the Campanians turned to Rome to aid them against the also-Oscan-speaking Samnites. The leading city of the Campanians was Capua, but as Fronda (op. cit.) notes, they were meaningful divisions among them; Capua’s very prominence meant that many of the other Campanians were aligned against it, a division the Romans exploited.

The Oscans struggled for territory in Southern Italy with the Greeks – told you we’d get to them. The Greeks founded colonies along the southern part of Italy, expelling or merging with the local inhabitants beginning in the seventh century. These Greek colonies have distinctive material culture (though the Italic peoples around them often adopted elements of it they found useful), their own language (Greek), and their own religion. I want to stress here that Greek religion is not equivalent to Roman religion, to the point that the Romans are sticklers about which gods are worshipped with Roman rites and which are worshipped with the ritus graecus (“Greek rites”) which, while not a point-for-point reconstruction of Greek rituals, did involve different dress, different interpretations of omens, and so on.

All of these peoples (except the Gauls) ended up in Rome’s alliance system, fighting as socii in Rome’s wars. The point of all of this is that this wasn’t an alliance between, say, the Romans and the “Italians” with the latter being really quite a lot like the Romans except not being from Rome. Rather, Rome had constructed a hegemony (an “alliance” in name only, as I hope we’ve made clear) over (::deep breath::) Latins, Romans, Etruscans, Sabines, Volsci, Marsi, Lucanians, Paelignians, Samnites, Campanians, and Greeks, along with some people we didn’t mention (the Falisci, Picenes – North and South, Opici, Aequi, Hernici, Vestini, etc.). Many of these groups can be further broken down – the Samnites consisted of five different tribes in a confederation, for instance.

In short, Roman Italy under the Republic was preposterously multicultural (in the literal meaning of that word) … and it turns out that’s why they won.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: The Queen’s Latin or Who Were the Romans, Part II: Citizens and Allies”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2021-06-25.