As for conditions on the eve of coal’s rapid rise in the late sixteenth century, they were actually even less intense. Following the Black Death, London’s population took centuries to recover, and by 1550 was still below its estimated medieval peak. Having once had over 70-80,000 souls, by 1550 it had only recovered to about 50,000. And the woodlands fuelling London were clearly still intact. Foreign visitors in the 1550s, who mostly stayed close to the city, described the English countryside as “all enclosed with hedges, oaks, and many other sorts of trees, so that in travelling you seem to be in one continued wood”, and remarked that the country had “an abundance of firewood”.1 Even in the 1570s, when London’s population had likely begun to finally push past its medieval peak, the city seems to have drawn its wood from a much smaller radius than before. Whereas in the crunch of the 1300s it seemingly needed to draw firewood from as far as 17 miles away over land, in the 1570s even a London MP, with every interest in exaggerating the city’s demands, complained that it only sometimes had to source wood from as far away as just 12 miles.2

And not far along the coast from the city were also the huge woodlands of the Weald, which stretched across the southeastern counties of Sussex, Surrey and Kent, and which did not even send much of their wood to London at all. Firewood from the Weald was not only exported to the Low Countries and the northern coast of France, but those exports more than tripled between 1490 and the early 1530s, from some 1.5 million billets per year to over 4.7 million. That level was still being reached in 1550, when not interrupted by on-and-off war with France, but by then the Weald was also meeting yet another new demand, for making iron.3

Ironmaking was extremely wood-hungry. In the 1550s Weald, making just a single ton of “pig” or cast iron, fit only for cannon or cooking pots, required almost 4 tons of charcoal, which in turn required roughly another 28 tons or so of seasoned wood. England in the early sixteenth century had imported the vast majority of its iron from Spain, but between 1530 and 1550 Wealden pig iron production increased eightfold. The expansion would have demanded, on a very conservative estimate, the sustained annual output of at least 50,000 acres of woodland — an area over sixty times the size of New York’s Central Park. Yet even this hugely understates the true scale of the expansion, as pig iron needed to be refined into bar or wrought iron in order to be fit for most uses, which required twice as much charcoal again — or in other words, a total of 86 tons of seasoned wood had to be first baked and then burned, just to make one ton of bar iron from the ore. And all this was just the beginning. By the 1590s the output of the Wealden ironworks had more than tripled again, for pig iron alone (though the efficiency of charcoal usage had also halved — a story for another time, perhaps).4

Given the rapidity of these changes, it will come as no surprise that there were complaints from the locals about how much the ironworks had increased the price of fuel for their homes. No doubt the wood being exported was having a similar effect as well. But the 1540s and 50s were also time of rapid general inflation, because of a dramatic debasement of the currency initiated by Henry VIII to pay for his wars. This not only made imports significantly more expensive, and so likely spurred much of the activity in the Weald to replace increasingly unaffordable iron from Spain, but they also made exports significantly cheaper for buyers abroad — and thus unaffordable for the English themselves.

In 1548-9, in a desperate bid to keep prices down, royal proclamations repeatedly and futilely banned the export of English wheat, malt, oats, barley, butter, cheese, bacon, beef, tallow, hides, and leather, to which the following year were added — like a game of inflation whack-a-mole — rye, peas, beans, bread, biscuits, mutton, veal, lamb, pork, ale, beer, wool, and candles. And of course charcoal and wood.5 For us to have records of the Weald exporting large quantities of wood in 1550 then, they must either have been sold through special royal licence, or have all been shipped out before the ban came in force just halfway through the year in May. Presumably a great deal more than recorded was also smuggled out. In 1555, parliament saw the need to put the ban on exporting victuals and wood into law, adding severe penalties. Transgressing merchants would lose their ship and have to pay a fine worth double the value of the contraband goods, while the ship’s mariners would see all their worldly possessions seized, and be imprisoned for at least a year without bail.6

It’s perhaps no wonder that the Weald’s ironworks continued to expand at such a rapid pace: the export ban would have freed up a great deal of woodland for their use. And ironmaking soon spread to other parts of England too, to where it did not have to compete for fuel with people’s homes. Given iron was significantly more valuable by both weight and volume than wood, it could easily bear the cost of transporting it from further away, and so could be made much further inland, away from the coasts and rivers whose woodlands served cities. In the early seventeenth century, iron ore and pig iron from the southwest of England was sometimes shipped all the way to well-wooded Ireland for smelting or refining into bar.7 In the early eighteenth century scrap iron from as far away as even the Netherlands was being recycled in the forested valleys of southwestern Scotland.8

Whenever ironmaking hit the limits of what could be sustainably grown in an area, it simply expanded into the next place where wood was cheap. And there was almost always another place. England, having had to import some three quarters of its iron from Spain in the 1530s, by the 1580s was almost entirely self-sufficient, after which the total amount of iron it produced using charcoal continued to grow, reaching its peak another two hundred years later in the 1750s.9 Had iron-making not been able to find sustainable supplies of fuel within England, it would have disappeared within just a few years rather than experiencing almost two centuries of expansion.10

And that’s just iron. The late sixteenth century also saw the rapid rise in England of a charcoal-hungry glass-making industry too. Green glass for small bottles had long been made in some of England’s forests in small quantities, but large quantities of glass for windows had had to be imported from the Low Countries and France. Just as with iron, however, the effect of debasement was to make the imports unaffordable for the English, and so French workers were enticed over in the 1550s and 60s to make window glass in the Weald. Soon afterwards, Venetian-style crystal-clear drinking glasses were being made there too.

What makes glass even more interesting than iron, however, is that its breakability meant it could not be made too far away from the cities in which it would be sold, and so had to compete directly with people’s homes for its fuel. Yet by the 1570s crystal glass was even being made even within London itself. Despite charcoal supplies being by far the largest cost of production, over the course of the late sixteenth century the price of glass in England remained stable, making it increasingly common and affordable while the price of pretty much everything else rose.11

What we have then is not evidence of a mid-sixteenth-century shortage of wood for fuel, and certainly not of those demands causing deforestation. It is instead evidence of truly unprecedented demands being generally and sustainably met.

And despite these unprecedented demands, the intensity with which under-woods were exploited for fuel seems to have actually decreased. During the medieval population peaks, the woods and hedges that supplied London had been squeezed for more fuel by simply cropping the trunks and branches more often, cutting them away every six or seven years rather than waiting for them to grow into larger poles or logs. After the Black Death killed off half the population, the cropping cycle could again lengthen to about eleven. But under-woods in the mid-sixteenth century were being cropped on average only twelve or so years — about twice as long a cycle as before the Black Death — which by the nineteenth century had lengthened still further to fourteen or fifteen.12

The lengthening of the cropping cycle can imply a number of things, and we’ll get to them all. But one possibility is that in order to meet unprecedented demands, more firewood was being collected at the expense of the other major use of trees: for timber.

Anton Howes, “The Coal Conquest”, Age of Invention, 2024-10-04.

1. Estienne Perlin, “A description of England and Scotland” [1558], in The Antiquarian Repertory, vol.1 (1775), p.231. Perlin must have visited Britain in early 1553, as he mentions the arrival of a new French ambassador, which occurred in April 1553, as well as the wedding of Lady Jane Grey, which occurred in May of that year. Also Danielo Barbaro, “Report (May 1551)” in Calendar of State Papers Relating to English Affairs in the Archives of Venice, Vol 5: 1534-1554 (Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1873). And: Paul Warde and Tom Williamson, “Fuel Supply and Agriculture in Post-Medieval England”, The Agricultural History Review 62, no. 1 (2014), p.71

2. Galloway et al., p.457 for the estimate of 17.4 miles overland as the outer limit of London’s firewood supply; Proceedings in the Parliaments of Elizabeth I, Vol I: 1558-1581, ed. T.E. Hartley (Leicester University Press, 1981), p.370: specifically, the London MP Rowland Hayward complained of the cost of firewood billets and charcoal having increased in price over the previous 30 years (which would encompass the period of debasement-induced inflation), before noting that “Sometimes the want of wood has driven the City to make provision in such places as they have been driven to carry it 12 miles by land”.

3. Mavis E. Mate, Trade and Economic Developments, 1450-1550: The Experience of Kent, Surrey and Sussex (Boydell Press, 2006), pp.83, 92, 101.

4. These statistics are derived from a combination of Peter King, “The Production and Consumption of Bar Iron in Early Modern England and Wales”, The Economic History Review 58, no. 1 (1 February 2005), pp.1–33 for the iron production estimates, and G. Hammersley, “The Charcoal Iron Industry and Its Fuel, 1540-1750”, The Economic History Review 26, no. 4 (1973), pp.593–613 for the estimates of how much charcoal, wood, and land was required at a given date to produce a given quantity of pig or bar iron.

5. Paul L. Hughes and James F. Larkin, eds., Tudor Royal Proclamations., Vol. I: The Early Tudors (1485-1553) (Yale University Press, 1964), proclamations nos. 304, 310, 318, 319, 345, 357, 361, 365, 366.

6. 1 & 2 Philip & Mary, c.5 (1555)

7. William Brereton, Travels in Holland, the United Provinces, England, Scotland and Ireland 1634-1635, ed. Edward Hawkins (The Chetham Society, 1844), p.147

8. T. C. Smout, ed., “Journal of Henry Kalmeter’s Travels in Scotland, 1719-20”, in Scottish Industrial History: A Miscellany, vol. 14, 4 (Scottish History Society, 1978), p.19

9. See King. Note that there was an interruption to this growth in the mid-seventeenth century, for reasons I mention later on.

10. There was a period in the early-to-mid seventeenth century when English ironmaking stagnated, but this was due to the growth of a competitive ironmaking industry in Sweden.

11. D. W. Crossley, “The Performance of the Glass Industry in Sixteenth-Century England”, The Economic History Review 25, no. 3 (1972), pp.421–33

12. Galloway et al. On cropping cycles in particular, see pp.454-5: they note how the average cropping of wood in their sample c.1300 was about every seven years, but by 1375-1400 — once population pressures had receded due to the Black Death — the average had increased to every eleven. See also Rackham, pp.140-1. John Worlidge, Systema agriculturæ (1675), p.96 mentions that coppice “of twelve or fifteen years are esteemed fit for the axe. But those of twenty years’ standing are better, and far advance the price. Seventeen years’ growth affords a tolerable fell”.

January 13, 2025

January 10, 2025

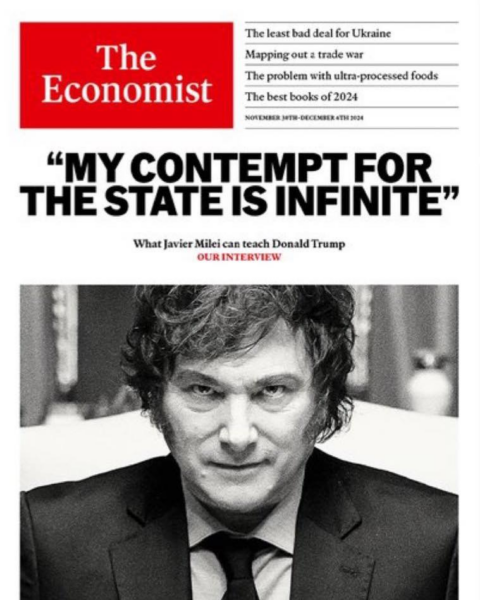

Javier Milei’s “devastation” and “social chaos” report card

In the Washington Examiner, David Harsanyi checks the current state of Argentina against the doom-and-gloom predictions from the start of Javier Milei’s term:

In the days leading up to the August 2023 presidential election in Argentina, a hundred “leading” economists from around the world, including progressive favorite Thomas Piketty, published an open letter warning that “radical right-wing economist” Javier Milei would inflict “devastation” and social chaos on his country.

However, they said it like it was a bad thing.

By the time Milei unexpectedly won the presidency, Argentina, once one of the wealthiest nations in the world, had a poverty rate of over 40% and the third-highest inflation rate in the world. After decades of Peronism, a toxic melding of fascism, socialism, and unionism, the nation bankrupted its central bank, and the peso was depreciating at warp speed. Do you think your mortgage rate is bad? Interest rates hit 118% in Argentina weeks before the election. The country was on its way to becoming another Venezuela. Milei wanted to blow it up.

After Milei’s unlikely victory, political scientist Ian Bremmer warned, “Economic collapse is coming imminently”. Felix Salmon, the chief financial correspondent at Axios, argued that Milei’s policies would plunge Argentina into “a deep recession”.

Seven months later, Argentina was out of a recession that had set in before Milei’s victory. The chainsaw-wielding economist, “el Loco” to friends, followed through on his promise of “shock therapy”, prioritizing taming inflation by cutting spending and deregulating the economy.

Almost all problems in modern Keynesian fixes are prominent features of governance in the modern West. Governments are always bragging about spending their way out of economic tribulations (tribulations they usually instigate). If a person suggests that free-market economic policy would have been more beneficial in the long term, they are forced to rely on a counterhistory. This is one reason why lots of elites are rooting against Milei, who argues that most of the West’s economic ills lie in Keynesian economics. They want him to fail.

As we all know, most panic-inducing cases of “austerity” are just minuscule reductions in the trajectory of spending growth. Not Milei’s plan, which entailed shutting down 13 government agencies and firing over 30,000 public workers — around 10% of the federal workforce. That is an unrivaled political revolution. Argentina’s federal budget was reduced by 30%. Even if the Department of Government Efficiency accomplished everything Elon Musk and Vivek Ramaswamy are talking about doing, they wouldn’t come close to 3%, much less 30%, in spending cuts. There has likely been no comparable austerity program in any Western economy.

By May 2024, Argentina recorded its first quarterly budget surplus since 2008. Inflation, still high, dropped from a debilitating 25% at the end of 2023 to 2.4% by the end of 2024. Per capita salary, having plunged, is now also recovering.

Dan Mitchell agrees that it’s easy to mock economists for their hair-on-fire reaction to Milei’s election:

Consider the supposedly prestigious left-leaning academics who asserted in 2021 that Biden’s agenda was not inflationary. At the risk of understatement, they wound up with egg on their faces.1

Today, we’re going to look at another example of leftist economists making fools of themselves.

It involves Argentina, where President Javier Milei’s libertarian agenda has yielded amazingly positive results in just one year.

- Dramatic lowering of inflation.

- Big reductions in the burden of government spending.

- Rapidly achieving a balanced budget.

- Reductions in poverty.

- Rising levels of household income.

Some of us knew that good policy would lead to good results.

Others, like the editors at Bloomberg, perhaps did not expect such a quick turnaround. But, to their credit, they just acknowledged the amazing progress in an editorial.

The U.K.-based Telegraph leans to the right, so this headline can probably be interpreted as a victory dance.

1. The bad monetary policy that led to rapidly rising prices actually began under Trump in 2020 and was continued by Biden in 2021.

January 4, 2025

November 28, 2024

How is Argentina doing after a year under Javier Milei?

I don’t normally follow South American news all that closely, as despite being in the same hemisphere, little that happens there has much importance to us here in Canada or the United States. The election of Argentinian President Javier Milei, however, has made Argentina a much more interesting place to watch as Milei valiantly attempts to turn the economy around from its near-century-long decline. Here, Dan Mitchell provides his assessment of Milei’s efforts so far:

… let’s focus today on Milei’s goal of maximizing economic liberty.

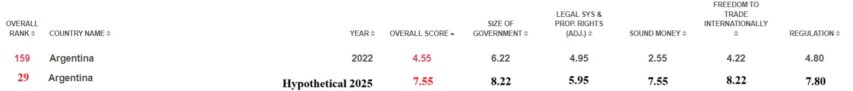

The bad news is that if he wants Argentina to become the new Hong Kong, Milei has a long journey. According to Economic Freedom of the World, Argentina ranked a lowly #159 out of 165 nations in 2022.

As you can see from the EFW rankings, Milei’s country gets especially bad scores for Sound Money, Trade and Regulation (dead last for Sound Money and in the bottom-10 percent of the world for the other two categories!).

The good news is that you don’t have to be libertarian Nirvana (or even Liberland) to make a big jump in the rankings.

You don’t even need to be Hong Kong (which used to be very good with scores above 9 but has now declined to 8.58 thanks to Beijing’s intervention).

Heck, almost every country in the western world has experienced a significant decline in economic liberty this century.

Milei actually could put Argentina in first place today merely by achieving the same level of economic liberty (8.67) that the United States had in 2004.

For what it’s worth, I think it would take several years of good reforms to climb that high.

That being said, dramatic improvements are nonetheless possible in a very short period. Here’s my back-of-the-envelope estimate of where Argentina could be by the end of next year.

November 10, 2024

The 1896 US Presidential election

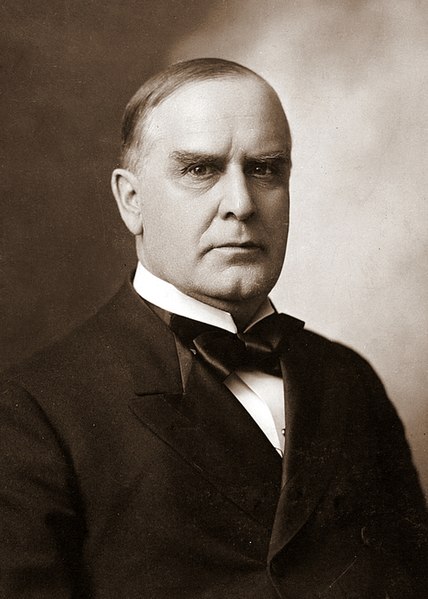

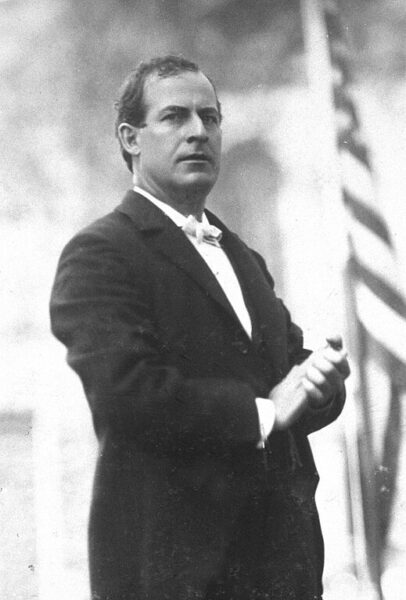

In the latest SHuSH newsletter, Ken Whyte looks back to the 1896 contest between William McKinley and William Jennings Bryan:

William Jennings Bryan, Democratic party presidential candidate, standing on stage next to American flag, 3 October 1896.

LOC photo LC-USZC2-6259 via Wikimedia Commons.

The 1880s and 1890s saw an enormous expansion in the number of newspapers in America. New printing technologies had drastically reduced barriers to entry in the newspaper field, while the emergence of consumer advertising was making the business more lucrative. By the election of 1896, there were forty-eight daily newspapers in New York (Brooklyn had several more), each vying for the attention of some portion of the city’s three million souls. The major papers routinely produced three or four editions a day, and as many as a dozen on a hot news day, making for a 24/7 news environment long before the term was coined. The individual newspapers were distinguished by their politics, ethnic, and class orientations. They advocated vigorously, often shamelessly, and occasionally dishonestly for the interests of their readers. Similar dynamics were afoot everywhere. America, in the 1890s, was noisy as hell.

Republican nominee William McKinley was the respectable candidate in 1896, heavily favoured. He had a state-of-the-art organization, buckets of money, and vast newspaper support, even among important Democratic publishers such as Joseph Pulitzer. The Democrats fielded William Jennings Bryan, who looked to be the weak link in his own campaign. He was a relatively unknown and untested ex-congressman from Nebraska, just thirty-six-years-old, a messianic populist with a mesmerizing voice and radical views. A last-minute candidate, he was selected on the convention floor over Richard P. Bland, against the protests of the party establishment.

Bryan broke all the norms of politics in 1896. At the time, it was believed that the dignified approach to campaigning was to sit on one’s porch and let party professionals speak on one’s behalf. Grover Cleveland had made eight speeches and journeyed 312 miles in his three presidential campaigns (1884, 1888, 1892). Bryan spent almost his entire campaign on the rails, holding rallies in town after town. He travelled 18,000 miles and talked to as many as five million Americans. He unabashedly championed the indigent and oppressed against Wall Street and Washington elites.

Inflation was the central issue of the 1896 campaign. The US was on the gold standard at the time, meaning that the amount of money in circulation was limited by the amount of gold held by the treasury. Gold happened to be scarce, resulting in an extended period of deflation, a central factor in the major economic depression of the early 1890s. The effects were felt disproportionately by the poor and working class. Bryan advocated the monetization of silver (in addition to gold) as a means of increasing the money supply and reflating the economy. This was viewed by the establishment as an economic heresy (not so much today). Bryan was viewed as a saviour by his followers, and that’s certainly how he saw himself.

The New York Sun heard among the Democrats “the murmur of the assailants of existing institutions, the shriek of the wild-eyed”. The New York Herald warned that Bryan’s supporters, disproportionately in the west and south, represented “populism and Communism” and “crimes against the nation” on par with secession. The New York Tribune warned that the Democrats’ “burn-down-your-cities platform” would lead to pillage and riot and “deform the human soul”. The New York Times asked, in all sincerity, “Is Mr. Bryan Crazy?” and spoke to a prominent alienist who was convinced that the election of the Democrat would put “a madman in the White House”. That Bryan’s support was especially strong among new Americans — the nation was amid an unprecedented wave of immigration — was especially disconcerting to the establishment. His followers were a “freaky”, “howling”, “aggregation of aliens”, according to the Times.

The only major New York newspaper to support the Democrats that season was Hearst’s New York Journal, a new, inexpensive, and wildly popular daily. I wrote about this in The Uncrowned King: The Sensational Rise of William Randolph Hearst. Loathed by the afore-mentioned respectable sheets, the Journal became the de facto publicity arm of the Bryan campaign and Hearst became the Elon Musk of his time.

The unobjectionable McKinley didn’t offer Democrats much of a target, but his campaign was being managed and funded by Ohio shipping and steel magnate Mark Hanna. The Journal had learned that Hanna and a syndicate of wealthy Republicans had previously bailed out McKinley from a failed business venture. Hearst’s cartoonists portrayed Hanna as a rapacious plutocratic brute (accessorized with bulging sacks of money or the white skulls of laborers) and McKinley as his trained monkey or puppet: “No one reaches the McKinley eye or speaks one word to the McKinley ear without the password of Hanna. He has McKinley in his clutch as ever did hawk have chicken … Hanna and his syndicate are breaking and buying and begging and bullying a road for McKinley to the White House. And when he’s there, Hanna and the others will shuffle him and deal him like a deck of cards.” The cartoons were criticized as cruel, distorted, and perverted. They were hugely effective.

Caught off guard by Bryan’s tactics, but unwilling to put McKinley on the road, Hanna instead arranged for 750,000 people from thirty states to visit Canton, Ohio and see McKinley speak from his front porch. He meanwhile made some of the most audacious fundraising pitches Wall Street had ever heard. Instead of asking for donations, he “levied” banks and insurers a percentage of their assets, demanding the Carnegies, Rockefellers, and Morgans pay to defend the American way from democratic monetary lunatics. Standard Oil alone coughed up $250,000 (the entire Bryan campaign spent about $350,000). Hanna printed and distributed a mind-boggling 250 million documents to a US population of about 70 million (the mails were the social media of the day), and fielded 1,400 speakers to spread the Republican gospel from town to town. All of this was unprecedented.

The Republicans generated their own conspiracy theories to counter the stories about Hanna’s controlling syndicate. Pulitzer’s New York World published a series of articles on The Great Silver Trust Conspiracy — “the richest, the most powerful and the most rapacious trust in the United States”. Bryan was said to be a puppet of this “secret silver society”, for which the World had no evidence beyond that the candidate was popular in silver mining states.

There were violent motifs throughout the campaign. The Republicans accused the Democrats of fostering division and rebellion, threatening national unity by pitting the south and the west against the east and the Mid-West. This was charged language with the Civil War still in living memory. Hanna funded a Patriotic Heroes’ Battalion comprising Union army generals who held 276 meetings in the last months of the campaign. They would ride out in full uniforms to a bugle call, advising the old soldiers who came out to see them to “vote as they shot”. Said one of their number: “The rebellion grew out of sectionalism … We cannot tolerate, will not tolerate, any man representing any party who attempts again to disregard the solemn admonitions of Washington to frown down upon any attempt to set one portion of the country against another.” Senior New York Republicans vowed that if the Democrats were elected, “we will not abide the decision”. These belligerent tactics were cheered by the majority of New York papers.

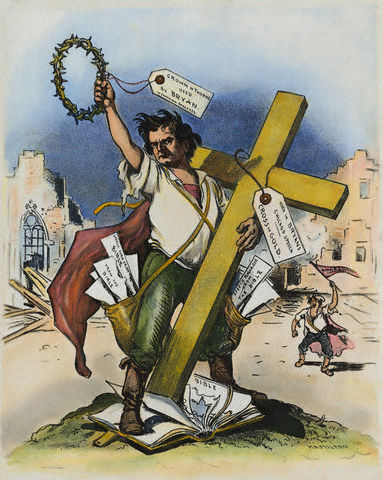

Democratic and populist leader William Jennings Bryan, climaxed his career when when he gave his famous “Cross of Gold” speech which won him the nomination at the age of 36.

Grant Hamilton cartoon for Judge magazine, 1896 via Wikimedia Commons.Bryan did nothing to cool tempers by claiming, in his famous “cross of gold” speech, that he and working-class Americans were being crucified by financial and political elites.

On it went. There were many echoes of 1896 in 2024. The polarized electorate, the last-minute candidate, record spending, unprecedented campaign tactics, populism and personal charisma, relentless ad hominem attacks, class and culture and regional warfare, inflation, immigration, racism, misinformation and conspiracy theories, comedians and plutocrats, threats of authoritarianism and violence and revolution, all of it massively amplified, and sometimes generated, by messy new media.

Of course, some of the echoes are coincidental, and there are also many contrasts. It was a different electorate. The alignment of the parties bore little resemblance to what we see today. Bryan, aside from his megalomania and zealotry, was as personally decent as Trump isn’t. And Bryan lost the campaign.

My point is I don’t think it’s an accident that the likes of Bryan and Trump — mavericks who thoroughly dominate their parties (both thrice nominated) through a direct and unshakeable bond with their followers — surface when the public sphere is most chaotic. New media environments, by their nature, are amateurish, turbulent, unsettling. There are fewer guardrails, which is a major reason outsiders and their followers gravitate to them. They see a way to change the rules and end-run established media (establishment candidates are naturally more comfortable using established channels to reach voters). New forms of political communication develop, contributing to new political norms, tactics, and strategies, and long-lasting political realignments.

For better or worse.

October 6, 2024

The rise of coal as a fuel in England

In the latest instalment of Age of Invention, Anton Howes considers the reasons for the rise of coal and refutes the frequently deployed “just so” story that it was driven by mass deforestation in England:

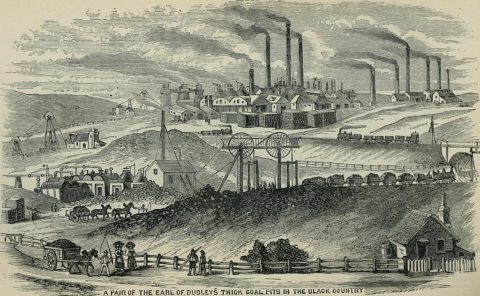

An image of coal pits in the Black Country from Griffiths’ Guide to the iron trade of Great Britain, 1873.

Image digitized by the Robarts Library of the University of Toronto via Wikimedia Commons.

It’s long bothered me as to why coal became so important in Britain. It had sat in the ground for millennia, often near the surface. Near Newcastle and Sunderland it was often even strewn out on the beaches.1 Yet coal had largely only been used for some very specific, small-scale uses. It was fired in layers with limestone to produce lime, largely used in mortar for stone and brick buildings. And it had long been popular among blacksmiths, heating iron or steel in a forge before shaping it into weapons or tools.2

Although a few places burned coal for heating homes, this was generally only done in places where the coal was an especially pure, hard, and rock-like anthracite, such as in southern Wales and in Lowlands Scotland. Anthracite coal could even be something of a luxury fuel. It was burned in the palaces of the Scottish kings.3 But otherwise, the sulphur in the more crumbly and more common coal, like that found near Newcastle, meant that the smoke reeked, reacting with the moisture of people’s eyes to form sulphurous acid, and so making them sting and burn. The very poorest of the poor might resort to it, but the smoke from sulphurous coal fires was heavy and lingering, its soot tarnishing clothes, furnishings, and even skin, whereas a wood fire could be lit in a central open hearth, its smoke simply rising through the rafters and finding its way out through the various crevices and openings of thatched and airy homes. Coal was generally the inferior fuel.

But despite this inferiority, over the course of the late sixteenth century much of the populated eastern coast of England, including the rapidly-expanding city of London, made the switch to burning the stinking, sulphurous, low-grade coal instead of wood.

By far the most common explanation you’ll hear for this dramatic shift, much of which took place over the course of just a few decades c.1570-1600, is that under the pressures of a growing population, with people requiring ever more fuel both for industry and to heat their homes, England saw dramatic deforestation. With firewood in ever shorter supply, its price rose so high as to make coal a more attractive alternative, which despite its problems was at least cheap. This deforestation story is trotted out constantly in books, on museum displays, in conversation, on social media, and often even by experts on coal and iron. I must see or hear it at least once a week, if not more. And there is a mountain of testimonies from contemporaries to back the story up. Again and again, people in the late sixteenth and the seventeenth centuries complained that the woods were disappearing, and that wood fuel prices were on the rise.

And yet the deforestation thesis simply does not work. In fact it makes no sense at all.

Not out of the Woods Yet

This should immediately be obvious from even just a purely theoretical perspective, because wood was almost never exploited for fuel as a one-off resource. It was not like coal or peat or oil, which once dug out of the ground and burned could only be replaced by finding more. It was not a matter of cutting swathes of forest down and burning every branch, stump and root, leaving the land barren and going off in search of more. Our sixteenth-century ancestors were not like Saruman, destroying Fangorn forest for fuel. Instead, acres of forest, and even just the shrubs and trees that made up the hedges separating fields, were carefully maintained to provide a steady yield. The roots of trees were left living and intact, with the wood extracted by cutting away the trunk at the stump, or even just the branches or twigs — a process known as coppicing, and for branches pollarding — so that new trunks or branches would be able to grow back. Although some trees might be left for longer to grow into longer and thicker wood fit for timber, the underwoods were more regularly cropped.4

Given forests were treated as a renewable resource, claiming that they were cut down to cause the price of firewood to rise is like claiming that if energy became more expensive today, then we’d use all the water behind a hydroelectric dam and then immediately fill in the reservoir with rubble. Or it’s like claiming that rising food prices would result in farmers harvesting a crop and then immediately concreting over their fields. What actually happens is the precise opposite: when the things people make become more valuable, they tend to expand production, not destroy it. High prices would have prompted the English to rely on forests more, not to cut them down.

When London’s medieval population peaked — first in the 1290s before a devastating famine, and again in the 1340s on the eve of the Black Death — prices of wood fuel began to rise out of all proportion to other goods. But London had plenty of nearby woodland — wood is extremely bulky compared to its value, so trees typically had to be grown as close as possible to the city, or else along the banks of the Thames running through it, or along the nearby coasts. With the rising price of fuel, however, the city did not even have to look much farther afield for its wood, and nearby coastal counties even continued to export firewood across the Channel to the Low Countries (present-day Belgium and the Netherlands) and to the northern coast of France.5 A few industries did try to shift to coal, with lime-makers and blacksmiths substituting it for wood more than before, and with brewers and dyers seemingly giving it a try. But the stinking smoke rapidly resulted in the brewers and dyers being banned from using it, and there was certainly no shift to coal being burnt in people’s homes.6

1. Ruth Goodman, The Domestic Revolution (Michael O’Mara Books, 2020), p.91

2. James A. Galloway, Derek Keene, and Margaret Murphy, “Fuelling the City: Production and Distribution of Firewood and Fuel in London’s Region, 1290-1400”, The Economic History Review 49, no. 3 (1996): pp.447–9

3. J. U. Nef, The Rise of the British Coal Industry, Vol. 1 (London: George Routledge and Sons, 1932), p.107, pp.115-8

4. Oliver Rackham, Ancient Woodland: Its History, Vegetation and Uses in England (Edward Arnold, 1980), pp.3-6 is the best and clearest summary I have seen.

5. Galloway et al.

6. John Hatcher, The History of the British Coal Industry: Volume 1: Before 1700: Towards the Age of Coal (Oxford University Press, 1993), p.25

October 2, 2024

Duelling reports on how Javier Milei’s Argentinian “shock therapy” is working

At Astral Codex Ten, Scott Alexander tries to find something approaching the truth between the pantingly enthusiastic libertarian reports and the angrily negative progressive reports:

How is Javier Milei, the new-ish libertarian president of Argentina doing?

According to right-wing sources, he’s doing amazing, inflation is vanquished, and Argentina is on the road to First World status.

According to left-wing sources, he’s devastating the country, inflation has ballooned, and Argentina is mired in unprecedented dire poverty.

I was confused enough to investigate further. Going through various topics in more depth:

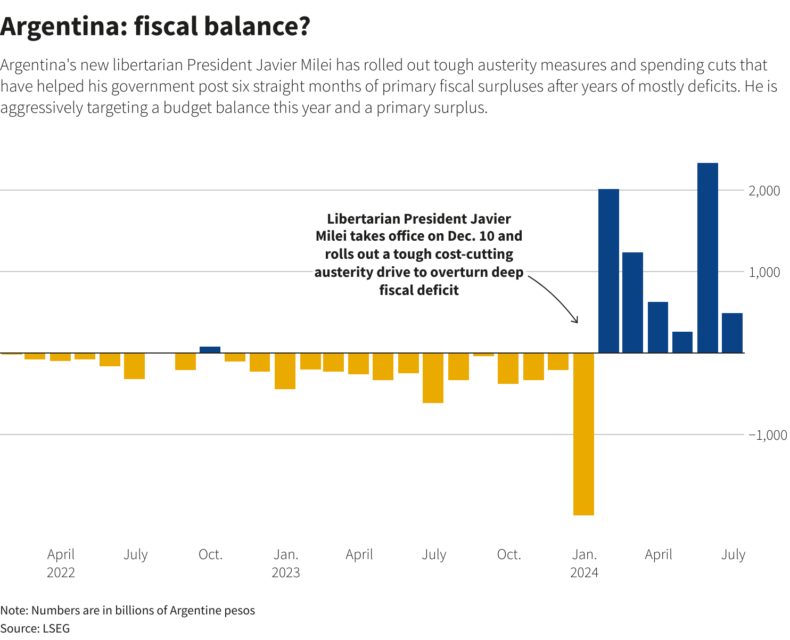

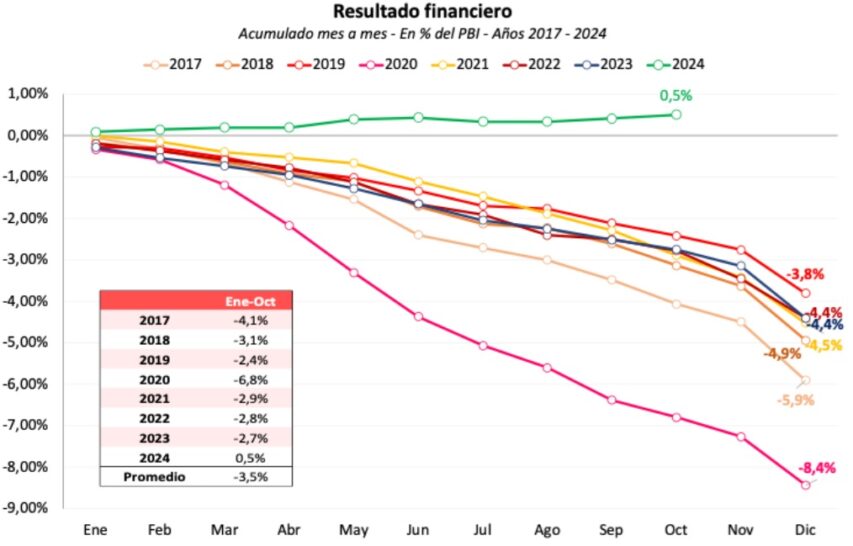

1: Government Surplus

When Milei was elected, Argentina went from constant deficits to almost unprecedented government surplus, and has continued to run a surplus for the past six months.

This wasn’t fancy macroeconomic magic. Milei just cut government spending:

- He eliminated 9 of 18 government ministries, including the Ministry of Culture and the Ministry of Women, Gender, and Diversity.

- He laid off 24,000 government workers (and hopes to increase that to 70,000).

- He cut fuel subsidies (paywalled link)

- He may have cut (or at least not increased, which given inflation levels is an effective cut) funding for universities, which now complain they have no electricity and are giving classes in the dark.

- He has changed the way inflation affects pensions in what was realistically a large budget cut.

- Et cetera.

This source says he cut the size of government by about 30% overall. Unsurprisingly, this eliminated the Argentine deficit.

[…]

6: Overall

When Javier Milei took office, he promised to do shock therapy that would short-term plunge Argentina into a recession, but long-term end its economic woes.

He has fulfilled his campaign promise to plunge Argentina into a recession. Whether this will long-term end its economic woes remains to be seen.

I think he gets credit for some purely political victories (completing the budget cuts he said he would complete), for decreasing inflation, and for improving the housing market. But in the end, history will judge him for whether his shock therapy eventually bears fruit. I don’t think that judgment can be made yet, and I don’t see many economists eager to go out on a limb and say that there are strong signs that his particular brand of shock therapy will definitely work/fail.

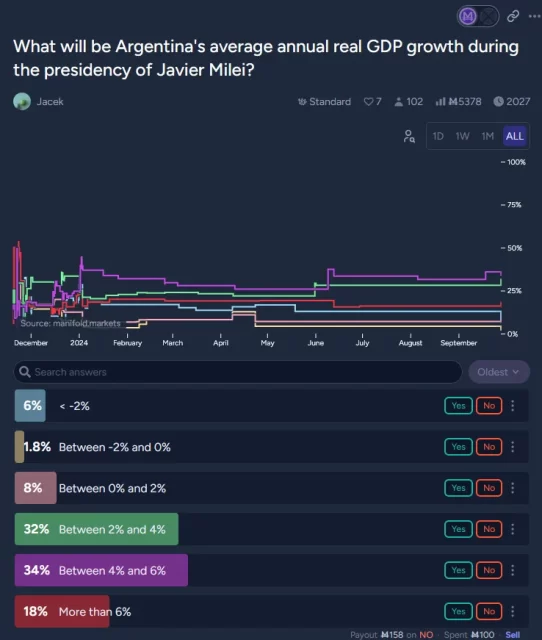

There are disappointingly few Milei prediction markets, probably because it’s hard to operationalize “he makes the economy good”. This multi-pronged mega-market has few traders, and weakly predicts a mix of good and bad things, maybe leaning a little good. But here is a more specific one:

… which compared to Argentina’s historical GDP growth rate seems — no, sorry, Argentina’s historical GDP growth rate is too weird to draw any conclusions.

And maybe the most important test:

September 29, 2024

The “Foundations” essay could apply equally to Canada’s doldrums as it does to Britain

Earlier this week, I linked to the “Foundations” essay by Ben Southwood, Samuel Hughes, and Sam Bowman and it struck me that so much of what they discuss about Britain’s stagnation applied at least as well to Canada. In the National Post, John Ivison concurs:

The “Foundations” essay pointed to moribund GDP per capita growth, among other data points, to make the argument that Britain is standing still economically. (Britain’s economy grew 0.7 per cent a year between 2002 and 2022, Canada’s increased 0.6 per cent a year in the same period, while U.S. output swelled 1.16 per cent a year.)

In relative terms, both countries are getting poorer: in 2002, Canada’s GDP per person was 81 per cent of the U.S.; in 2022, it was 72 per cent. The same figures for the U.K. against the U.S. are 78 per cent in 2002 and, 70 per cent in 2022.

The reason for Britain’s stagnation, the authors argue, is that it has effectively banned investment in transportation, energy and housing — “the foundations it needs to grow.”

Sound familiar?

“The most important economic fact about modern Britain is that it is difficult to build almost anything, anywhere. This prevents investment, increases energy costs and makes it harder for productive economic clusters to expand,” the authors write, saying the result is lower productivity, incomes and tax revenues.

They argued that Britain needs a program of reform with the scale and ambition of the liberalization of the 1980s that focused on cutting taxes, curbing union power and privatizing state-run industries.

“This time we must focus on making it easier to invest in homes, labs, railways, roads, bridges, interconnectors and nuclear reactors,” they write.

That’s a difficult proposition for politicians who are able to resist anything except the temptation to use resources for immediate electoral gratification, rather than investing for a time after they have left office.

Both Canada and Britain are laggards when it comes to investment in infrastructure. While China spent more than five per cent of its GDP on roads, bridges and other infrastructure in 2021, Canada invested just 0.5 per cent (down from 1.3 per cent in 2010) and the U.K. 0.9 per cent.

But the lack of dynamism is not simply political expediency. Rather, it is motivated by an indifference, even a hostility, toward building critical infrastructure.

The Foundations report noted that Britain has not built a reservoir for 30 years, yet faces chronic water shortages in the east of England. Its environmental agency has blocked new development on the basis that it could only be supplied with water by draining environmentally valuable chalk streams. The result is that England’s innovation hub, Cambridge, is barred from expanding, which threatens to strangle the country’s life-sciences industry.

Similar impulses are at work in Canada. Federal Environment Minister Steven Guilbeault said in February that Ottawa would stop investing in new road infrastructure — a position he later clarified to say meant the federal government would not fund large projects like a highway tunnel connecting Quebec City and Levis, Que.

That same sentiment is reflected in the federal Liberal government’s Impact Assessment Act, passed in 2019, which slowed the pace and increased the cost of major project approvals.

On the housing front, a generation of activists emerged who were intent on preventing urban sprawl yet were also opposed to building mid-rise buildings of the kind that eased housing pressures in continental Europe. Constraints on approval are a major contributor to the 3.5-million-unit housing gap because supply has not kept pace with demand.

The consequence of Canada’s regulatory sclerosis is what business veteran Paul Deegan and former clerk of the Privy Council Kevin Lynch in an FP Comment article earlier this year referred to as “an insidious stealth tax on Canadian jobs and growth“.

Taking each of the “foundations” in turn, the depth of the problem becomes clearer — but so do the solutions.

September 24, 2024

British stagnation – “at some point it becomes impossible to grow when investment is banned”

Ed West reviews a new essay by Ben Southwood, Samuel Hughes, and Sam Bowman which tries to identify the underlying reasons for British economic stagnation:

The theme running through the essay is that the British system makes it very hard to invest and extremely expensive and legally difficult to build, making housing and energy costs prohibitive.

While we all know we have fallen in status, “most popular explanations for this are misguided. The Labour manifesto blamed slow British growth on a lack of “strategy” from the Government, by which it means not enough targeted investment winner picking, and too much inequality. Some economists say that the UK’s economic model of private capital ownership is flawed, and that limits on state capital expenditure are the fundamental problem. They also point to more state spending as the solution, but ignore that this investment would face the same barriers and high costs that existing infrastructure projects face, and that deters private investment.”

The problem is that “all of these explanations take the biggest obstacles to growth for granted: at some point it becomes impossible to grow when investment is banned”.

Even before the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the industrial price of energy had tripled in under 20 years. Per capita electricity generation in Britain is only two-thirds that of France, and a third of the US, making us closer to developing countries like Brazil and South Africa than other G7 states. Transport projects are absurdly expensive, mired by planning rules, and all of this helps explain why annual real wages for the median full-time worker are 6.9 per cent lower than in 2008.

In one of the most notorious examples, the authors note that “the planning documentation for the Lower Thames Crossing, a proposed tunnel under the Thames connecting Kent and Essex, runs to 360,000 pages, and the application process alone has cost £297 million. That is more than twice as much as it cost in Norway to actually build the longest road tunnel in the world.”

Britain’s political elites have failed, they argue, because they do not understand the problems, so “they tinker ineffectually, mesmerised by the uncomprehended disaster rising up before them”.

Even “before the pandemic, Americans were 34 percent richer than us in terms of GDP per capita adjusted for purchasing power, and 17 percent more productive per hour … The gap has only widened since then: productivity growth between 2019 and 2023 was 7.6 percent in the United States, and 1.5 percent in Britain … the French and Germans are 15 percent and 18 percent more productive than us respectively.” The gap continues to widen, and on current trends, Poland will be richer than the United Kingdom by the end of the decade.

Britain began to fall behind after the War, but after decades of relative stagnation, its GDP per capita had converged with the US, Germany and France in the 1980s, and our relative wealth peaked in the early Blair years. (Personally, I wonder if one reason for the great Oasis nostalgia is simply that we were rich back then.) If Britain had continued growing in line with its 1979-2008 trends, average income today would be £41,800 instead of £33,500 — a huge difference.

France is the most natural comparison point to Britain, a country “notoriously heavily regulated and dominated by labour unions”. This is sometimes comical to British sensibilities, so that “French workers have been known to strike by kidnapping their chief executives – a practice that the public there reportedly supports – and strikes are so common that French unions have designed special barbecues that fit in tram tracks so they can grill sausages while they march.” Only in France.

It is also heavily taxed, especially in the realm of employment, and yet despite this, French workers are significantly more productive. The reason is that France “does a good job building the things that Britain blocks: housing, infrastructure and energy supply”.

With a slightly smaller population, France has 37 million homes compared to our 30 million. “Those homes are newer, and are more concentrated in the places people want to live: its prosperous cities and holiday regions. The overall geographic extent of Paris’s metropolitan area roughly tripled between 1945 and today, whereas London’s has grown only a few percent.” One quality-of-life indicator is that “800,000 British families have second homes compared to 3.4 million French families“.

They also do transport far better, with 29 tram networks compared to seven in Britain, and six underground metro systems against our three. “Since 1980, France has opened 1,740 miles of high speed rail, compared to just 67 miles in Britain. France has nearly 12,000 kilometres of motorways versus around 4,000 kilometres here … In the last 25 years alone, the French built more miles of motorway than the entire UK motorway network. They are even allowed to drive around 10 miles per hour faster on them.”

August 30, 2024

Experts are concerned that criticism of experts will weaken their role in our political system

In the National Post, Geoff Russ dares to imply that the experts are not the divinely inspired superior beings with unfailing wisdom about any and all issues:

So-called “experts” have weakened Canada’s political discourse far more than Pierre Poilievre ever has. Journalist and author Stephen Maher recently penned a column in the Globe & Mail titled, “By slamming experts, Pierre Poilievre and his staff are degrading political debate”.

Maher is an even-handed journalist, and his column should not be written off as the scribblings of a Liberal partisan. What his column misses is how the term “expert” has been abused, and the degree to which “experts” have thoroughly discredited themselves in recent years.

Poilievre’s criticisms of the “experts” would not resonate if they lived up to the title bestowed upon them.

For example, the Doug Ford government’s decision to close 10 safe injection sites after implementing a ban on such facilities located near schools and child-care centres. The closures were lamented by “experts” trotted out by the CBC as putting peoples’ lives at risk.

The safe injection sites slated to be shut down are near schools and daycares, and there is demonstrable proof that crime rises near these sites wherever they are located.

Derek Finkle recently wrote that the critiques of the closures levelled by selected “experts” failed to note how community members had been threatened with rape, arson, and murder since the injection site in his Toronto neighbourhood had been opened.

These are reasonable grounds for a government to reconsider whether they should allow drug-use, supervised or not, to proliferate in neighbourhoods where families reside.

For all their alleged expertise, many “experts” seem unwilling to actually investigate what is happening on the ground, and often give plainly bad advice altogether, and this goes back decades.

The “experts” failed to predict the 2008 financial crisis, they said the risk to Canadians from the coronavirus was low in early 2020, and they failed to prevent runaway inflation after the worst of it had subsided.

Was it not the “experts” who asserted that arming and funding of Ukraine prior to Vladimir Putin’s invasion in 2022 was a bad idea? After the invasion began, was it not the “experts” who confidently predicted Putin’s army would conquer the whole of Ukraine in a matter of days, and not be bogged down in a years-long conflict that would reshape global trade?

The truth is that we live in a worse-off world because of the advice and predictions of “experts”.

August 27, 2024

Was 1974 the worst year in British politics or just the worst year so far?

I wasn’t in the UK in 1974 (although I did spend a couple of dystopian weeks there in January 1979), so I don’t know from personal experience just how bad things were, but as Ed West considers Dominic Sandbrook’s very informative social history Seasons in the Sun, he certainly helps make a strong case for it:

One of my favourite moments from reading Fever Pitch as a teenager was the passage where Nick Hornby and a friend bunk off school to watch Arsenal play West Ham, a game which was being held on a weekday afternoon because there wasn’t enough electricity for the floodlights. Britain was enduring a three-day week due to the energy crisis, and assuming the ground would be empty, Hornby is stunned to find it packed with 60,000 people, all skiving off work, and he recalls his hypocritical juvenile disgust at the idleness of the British public.

The scene encapsulates the comic crapness of that period, one that many of us have enjoyed laughing at with the recent Rest is History series on 1974. I began reading Sandbrook’s book Seasons in the Sun afterwards, from where the material for the series was drawn; the early chapters comprise a highly entertaining account of what he described on the podcast as “the worst year in British politics”. Reassuring, perhaps, for those of us inclined towards pessimism, although to paraphrase Homer Simpson, perhaps it was only the worst year so far.

Nineteen-seventy-four saw two elections, the first of which ended in a hung parliament, with Labour as the largest party, and the second with Harold Wilson winning with a majority of 3. These were fought between parties led by exhausted leaders who had run out of ideas, with a third, the Liberals headed by Jeremy Thorpe, soon to be notorious as a dog killer. Britain had declined from the richest country on the continent to one of the poorest in western Europe, and its economy seemed to be falling apart.

During his troubled four years in office Edward Heath had called a state of emergency several times, culminating in ration cards for petrol and power restrictions. In 1973 Heath had “told his Chancellor, Anthony Barber, to go for broke”, Sandbrook writes: “It was one of the greatest economic gambles in modern history: while credit soared and the money supply boomed, Heath hoped to keep inflation down through an elaborate system of wage and price controls”. By October that year, “his hopes were unravelling at terrifying speed”.

The “Barber boom” led to “house prices surging by 25 per cent in just six months, the cost of imports rocketing and Britain’s trade balance plunging deep into the red”. Yet just a week after Heath had published details of his “Stage Three” incomes policy, “the Arab oil exporters in the OPEC cartel announced a stunning 70 per cent increase in the posted price of oil, punishing the West for its support for Israel. It was a devastating blow to the world economy, but nowhere was its impact greater than in Britain.”

The stock market lost a quarter of its value in just a month, while by January 1974 share prices had fallen by almost half in under two years. Just before Christmas, the government cut spending by 4 per cent, and Labour’s Shadow Chancellor, Denis Healey, “warned his colleagues that Britain stood on the brink of an ‘economic holocaust'”. Nine out of ten people told a Harris poll that “things are going very badly for Britain” and nearly as many foresaw no improvement in the coming year. They turned out to be correct.

Amid trouble with the National Union of Mineworkers, in November 1973 “Heath announced his fifth state of emergency in barely four years. Floodlighting and electric advertising were banned; behind the scenes, the government began printing petrol ration cards. As the railwaymen voted to join the miners in pursuit of higher pay, it seemed that Britain was sliding into darkness. Offices were ordered to turn down their thermostats, while the BBC and ITV were banned from broadcasting after 10.30 at night. On New Year’s Day, with fuel supplies running dangerously low, the entire nation went on a three-day working week.” Happy days.

August 9, 2024

Rare signs of growth in the Argentine economy

It looks as if Argentina is managing a trick that Justin Trudeau can’t manage — growing the national economy while keeping inflation down:

During his first year as president, Javier Milei has been waging a bitter but largely successful campaign against inflation.

Now, Argentines received more welcome news: their economy is growing again.

“Economic activity rose 1.3 percent from April, above the 0.1 percent median estimate from analysts in a Bloomberg survey and the first month of growth since Milei’s term began in December,” Bloomberg reported on July 18. “From a year ago, the proxy for gross domestic product grew 2.3 percent.”

The positive economic report, based on data from the Argentine government, is a surprise to many.

The 2.3 percent year-over-year increase defied expectations of a decline of similar magnitude, Bloomberg reported. As Semafor notes, the Argentine economy was projected to have the least economic growth of any country in the world in 2024, according to the International Monetary Fund.

A “Wrecking Ball”?

Argentine economists I spoke to said that the numbers are encouraging, but the country’s economy is far from being out of the woods.

As most people know, Milei inherited an economic mess decades in the making. When the self-described anarcho-capitalist assumed office in December, Argentina was suffering from the third highest inflation rate in the world — 211 percent year over year. The poverty rate was north of 40 percent, and Argentina’s economy was declining.

With his country’s economy in a full tailspin from decades of Peronism, Milei proposed a series of economic reforms dubbed “shock therapy” that consisted primarily of three components: slashing government spending, cutting bureaucracy, and devaluing the peso.

Critics warned that these measures would be disastrous, and many took it for granted that the remedies would deepen Argentina’s recession.

The former head of the International Monetary Fund’s Western Hemisphere Department, Alejandro Werner, said Milei’s strategy could tame inflation, but at great cost.

“A deep recession will also take place,” Werner wrote, “as the fiscal consolidation kicks in and as the decline in household income depresses consumption and uncertainty weighs on investment.”

Felix Salmon, the chief financial correspondent at Axios, concurred, comparing Milei’s policies to “a wrecking ball”.

“Milei’s budget cuts will cause a plunge in household income, as well as a deep recession,” wrote Salmon.

Despite these warnings, Milei delivered his “shock therapy” plan in the first few months of his presidency. Tens of thousands of state workers were cut as were more than half of government ministries, including the Ministry of Culture, as well as the Ministries of Labor, Social Development, Health, and Education (which Milei dubbed “the Ministry of Indoctrination“). Numerous government subsidies were eliminated, and the value of the peso was cut in half.

Even before Milei’s policies were given a chance to succeed, many continued to attack them.

“Shock therapy is pushing more people into poverty,” journalist Lautaro Grinspan wrote in Foreign Policy in early March. “Food prices have risen by roughly 50 percent, according to official government data.”

Yet the official government data Grinspan cited was a report from December 2023, before Milei had even assumed the presidency.

Contrary to the dire predictions, the results of Milei’s policies have been better than even many of his supporters had dared hope.

During the first half of 2024, inflation cooled for five straight months in Argentina, the Associated Press reported in July. Though consumer prices were up 4.6 percent in June from the previous month, that’s down from a 25 percent month-over-month increase in December, when monthly inflation peaked in Argentina. Meanwhile, in February the government saw its first budget surplus in more than a decade. And just days ago, an economic report was published showing a massive decline in poverty in Argentina.

Many doubted that these successes were possible, and the conventional wisdom said that wringing inflation out of the economy and slashing government spending could only be achieved at great cost: a deepening recession.

July 30, 2024

The new and improved malaise for the 21st century

Back in the 1970s, US President Jimmy Carter identified the theme of the decade as “malaise”, and now, thanks to generations of feckless politicians, burgeoning bureaucratic empires, and economic stagnation, it’s back in an even malaisier form for the Current Year:

“Kamala Harris” by Gage Skidmore is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0 .

Some time ago, I noticed that a general fatigue had taken a place alongside the malaise that was already being felt by many Americans and Canadians. The malaise stemmed from the overdue recognition that their lives were not going to get any better, and that they would have to work harder to just maintain a standard of living that they were already used to.

The fatigue came from a different, but not too distant place; the politicization of everything these past one and a half decades meant that there was no escape [from] the political. Whether sports, video gaming, or even fashion, everything had to be run by the cultural police before it could be deemed “not problematic”. The problem was (and still is) that everything to this type is “problematic”. This would not be a problem at all if this type were not empowered by the powers-that-be, but for some strange reason the cultural police quickly became ubiquitous, and their constant hectoring and lecturing ground most people down to the point where fatigue set in.

Everything became political, so therefore there was nothing that was not political. The fact that sanctions began to be placed against those who dared to buck the new trends in social mores meant that this was a totalizing form of politics. It wasn’t fascism, nor was it communism … but it was (and is) totalitarianism in a new form all its own. The rise of populism on the right in the West (as this trend is also present in Europe, but is not as thoroughly embedded there as it is in North America) is almost entirely a reaction to this. Freedom and liberty, as traditionally understood in the Anglosphere (i.e. “as long as I don’t harm others, I can do or say what I want”) took a back seat to what they call “equality”, a first step towards the more extreme demand known as “equity”.

Economic precariousness combined with the permanent presence of the Sword of Damocles above your head is a brilliant way to get people to shut up and get with the program. It is very coercive, but it is for the “greater good”, they tell us. What we already see is that it does not convince all, and that it has a negative effect on trust in governing institutions and national elites. The level of control by the managerial elite over the daily lives of its citizens is now at a micro-management one. Everyday, most people have to think carefully before speaking for fear of committing some aggression that could lead to the termination of their employment. They must mouth elite-approved social mores just in order to be able to tread water, as boat rocking is a secular sin. Why would the powers-that-be want to ever give up such a tool of mass control? The people are not to be trusted, which is why this totalizing system must remain in place. Just imagine if it were removed: the dreaded 1990s would return … or something.

Jacob Siegel has written an interesting essay on the concept known as “Whole of Society”, and how it has become a totalizing system:

To make sense of today’s form of American politics, it is necessary to understand a key term. It is not found in standard U.S. civics textbooks, but it is central to the new playbook of power: “whole of society“.

The term was popularized roughly a decade ago by the Obama administration, which liked that its bland, technocratic appearance could be used as cover to erect a mechanism for the government to control public life that can, at best, be called “Soviet-style”. Here’s the simplest definition: “Individuals, civil society and companies shape interactions in society, and their actions can harm or foster integrity in their communities. A whole-of-society approach asserts that as these actors interact with public officials and play a critical role in setting the public agenda and influencing public decisions, they also have a responsibility to promote public integrity.“

In other words, the government enacts policies and then “enlists” corporations, NGOs and even individual citizens to enforce them — creating a 360-degree police force made up of the companies you do business with, the civic organizations that you think make up your communal safety net, even your neighbors. What this looks like in practice is a small group of powerful people using public-private partnerships to silence the Constitution, censor ideas they don’t like, deny their opponents access to banking, credit, the internet, and other public accommodations in a process of continuous surveillance, constantly threatened cancellation, and social control.

The catch:

“The government” — meaning the elected officials visible to the American public who appear to enact the policies that are carried out across the whole of society — is not the ultimate boss. Joe Biden may be the president but, as is now clear, that doesn’t mean he’s in charge of the party.

Siegel writes that the “whole of society” approach arose during Obama’s shift away from the War on Terror to something called “CVE” (Countering Violent Extremism) i.e. the shift away from focusing on Islamist terror towards fighting America’s own citizens who are not with the new political, social, and cultural programs:

But the true lasting legacy of the CVE model was that it justified mass surveillance of the internet and social media platforms as a means to detect and de-radicalize potential extremists. Inherent in the very concept of the “violent extremist”, was a weaponized vagueness. A decade after 9/11, as Americans wearied of the war on terror, it became passé and politically suspicious to talk about jihadism or Islamic terrorism. Instead, the Obama national security establishment insisted that extremist violence was not the result of particular ideologies and therefore more prevalent in certain cultures than in others, but rather its own free-floating ideological contagion. Given these criticisms Obama could have tried to end the war on terror, but he chose not to. Instead, Obama’s nascent party state turned counterterrorism into a whole-of-society progressive cause by redirecting its instruments — most notably mass surveillance — against American citizens and the domestic extremists supposedly lurking in their midst.

A reflection on the 20-year anniversary of Sept. 11 written in 2021 by Nicholas Rasmussen, the former director of the U.S. National Counterterrorism Center, captures this view. “Particularly with the growing threat to public safety and security posed by domestic violent extremism, it is essential that we move beyond the post-9/11 counterterrorism strategy paradigm that placed the government at the center of most counterterrorism work.” Instead of expecting the government to deal with terrorist threats, Rasmussen advocated for “a much wider, more expansive and inclusive ‘whole-of-society’ approach” that he said should encompass “state and local governments, but also the private sector (to include technology companies), civil society in the form of both individual voices and non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and academia.”

July 19, 2024

Argentina’s decades-long struggle with inflation

At the Foundation for Economic Education, Marcos Falcone provides an update on President Javier Milei’s ongoing efforts to drag the Argentine economy back from hyperinflation:

As Javier Milei rose to power in December of last year, Argentina suffered from an annual inflation rate of over 211 percent, only behind Venezuela and Lebanon. Having risen consistently for over two decades, a combination of perpetually unbalanced budgets and investors’ distrust made money creation (and thus inflation) almost unavoidable.

In that context, Javier Milei’s first promise in his inaugural address was to avoid hyperinflation. In order to do that, his highest priority was to balance the budget so as to stop monetizing the deficit. And indeed, after just one month, the government announced in January that Argentina achieved its first financial surplus in 16 years. In successive months, the budget has been kept balanced.

Quick action seems to be causing quick effects. Indeed, inflation has plunged from 25 percent in December to an expected 4 percent in July. This is happening in a context of price readjustments, with prices like rent going down (after the government repealed rent control laws) and energy and transport prices going up (as the government is cutting subsidies). Even the IMF has admitted that inflation is falling faster than expected. In fact, inflation is coming down so fast that banks have started offering mortgages for the first time in seven years. This signals that the market expects inflation to stay down.

Milei told Argentines that the process of defeating inflation would hurt—and it has. The downside of the government’s economic plan is that the country has entered a recession which is likely to last until at least the end of the year. Amid some layoffs, the country’s industrial output is decreasing. The spending cuts that allowed the country to balance the budget have resulted in less income for provinces and specific groups like retirees.

July 4, 2024

Argentina’s inflation rate

As you may have noticed, my interest in Argentinian affairs increased a lot with the election of Javier Milei as President. His first six months in office, while turbulent, do seem to have the economic indicators moving in the right direction for ordinary Argentines:

Argentina’s inflation rate has recently dropped to its lowest point since January 2022, registering a monthly increase of 4.2 percent in May according to the National Institute of Statistics and Census (INDEC). Although annual inflation has slowed for the first time since mid-2023, it still stands at 276.4 percent, one of the highest rates globally.

When Javier Milei assumed the presidency in December 2023, monthly inflation had skyrocketed to an unprecedented 25.5 percent. Within five months, Milei’s administration managed to reduce this figure by more than 20 percentage points. Despite the persistently high annual inflation rate, the trend indicates potential stabilization of the Argentine economy.

Javier Milei’s reforms have been described as aggressive. In his inaugural speech, he emphasized the need to clean up the economy before implementing his promises to dollarize and close the central bank.

To achieve a zero deficit, Milei enacted a 35 percent reduction in public spending. He achieved this by closing half of the ministries and secretariats, suspending public works for a year, reducing subsidies for energy and transportation, canceling government advertising, and maintaining the 2023 budget for 2024 despite an inflation rate of 300 percent. Essentially, the government drastically cut its expenditures.

These measures, although unpopular, yielded results. Milei’s government not only avoided a deficit, but achieved a surplus, and most importantly, inflation began to decline.

Following the inflation story in Argentina recently brought to mind Henry Hazlitt’s famous 1978 article “Inflation in One Page“. As the title suggests, Hazlitt summarizes the causes and remedies of inflation in a brief and simple explanation. He argued that inflation is a consequence of government monetary policies, specifically excessive money printing due to unbalanced budgets caused by extravagant government spending.

Subscribe for more insights on global economics, history, and leadership!

Subscribe for more insights on global economics, history, and leadership!