SandRhoman History

Published 7 Feb 2021Everybody quarrels over the efficacy of the English longbow. Many historians, reenactors and history enthusiasts alike hold the view that arrows piercing armor is a myth. Some base this view on testing as was done for example by Tod from Tod’s workshop. Together with his team, he provided an invaluable data point for this debate. Others, such as traditionalist historians are often open to the possibility of arrows piercing armor, even though they are aware of actual testing of the longbow. In general, the efficacy of a weapon is much more complicated than its mere armor penetration value. So, in this video we’d like to shed light on the whole debate and explain why it is so hard to find common ground on this issue. This is why everybody disagrees on the efficacy of the English longbow.

Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/sandrhomanhis…

Twitter: https://twitter.com/Sandrhoman

Tod’s Video: ARROWS vs ARMOUR – Medieval Myth Busting https://youtu.be/DBxdTkddHaE

Tod’s playlist: MEDIEVAL MYTH BUSTING https://youtube.com/playlist?list=PLI…

Bibliography:

Rogers, C.J., The Efficacy of the English Longbow, 1998.

Devries, K., Medieval Military Technology, 1994.

Bane, M., “English Longbow Testing against various armor circa 1400”, 2006.

Soar, H., Gibbs, J., Jury, C., Stretton, M., Secrets of the English War Bow. Westholme, 2010, pp. 127–151.

Magier, Mariusz; Nowak, Adrian; et al., “Numerical Analysis of English Bows used in Battle of Crécy”. Problemy Techniki Uzbrojenia. 142 (2), 2017, 69–85.

February 8, 2021

Why Everybody Disagrees on the Efficacy of the English Longbow – A Video Essay

February 4, 2021

The New World: A Beautiful Mess

Atun-Shei Films

Published 3 Feb 2021A review of the Terrence Malick film The New World, a lavish and beautifully shot historical epic that nonetheless falls short in a few important ways.

Support Atun-Shei Films on Patreon ► https://www.patreon.com/atunsheifilms

Leave a Tip via Paypal ► https://www.paypal.me/atunsheifilms

Buy Merch ► teespring.com/stores/atun-shei-films

#TerrenceMalick #Jamestown #Pocahontas

Original Music by Dillon DeRosa ► http://dillonderosa.com/

Reddit ► https://www.reddit.com/r/atunsheifilms

Twitter ► https://twitter.com/atun_shei

January 26, 2021

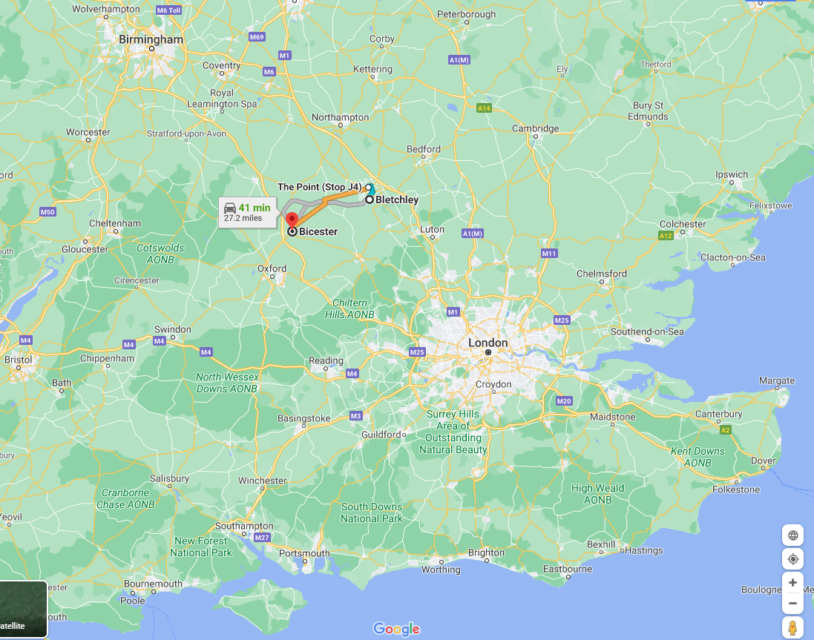

£760m to connect Bicester and Bletchley? That’s … very spendy

At the Continental Telegraph, Tim Worstall looks at the economic case for building the East-West railway line — in “reverse Beeching” style — to connect Oxford and Cambridge:

The cash from the Department of Transport will be used to lay track along a disused railway line between Bicester and Bletchley, in Buckinghamshire, with services beginning in 2025.

Excuse me? £760m to link Bicester and Bletchley? Other than the fact that that is £50m/mile, which should be the cost of rail lines made from crushed Faberge eggs and unicorn hair, how many people want to travel between Bicester and Bletchley by train? That’s roughly £10K/person in those small towns. OK,that then extends to Oxford, but that allows around 30,000 more people to go by train to Oxford. Which is not a particularly busy commuter metropolis anyway.

The aim is to complete the whole project by the end of the decade, according to the government minister overseeing it.

2 miles per year? Are they going to use canals and horses like Brunel?

[…]

Elsewhere, the new railway will shorten journey times between routes outside of London. Travellers from Oxford for example, will no longer have take a train into the capital and back out again to reach Milton Keynes, but could travel there via Bicester.

Again, what’s the demand for this? How many people want to do this, and would it be cheaper to just hire some chauffeurs to drive each passenger in a Ferrari from Bicester to where they want in Milton Keynes? I doubt it will be any quicker than a car because this only gets you to Bletchley, and then you have to get off a train to get to Milton Keynes, and then get where you want in Milton Keynes.

This used to be an active railway corridor before the Beeching cuts in the 1960s, which slashed a lot of uneconomic branch lines from British Rail’s network. If the land wasn’t sold off, then it’s just a matter of re-laying the track and ensuring that any existing bridges, embankments and drainage culverts are still capable of handling the renewed rail traffic. It seems unlikely that the mere engineering aspects of the project would require several hundred million pounds to complete, so perhaps there are some land issues that need to be re-acquired to allow the railway to become active again.

January 22, 2021

QotD: The enclosure movement, in historical fact and in Marxist imagining

Consider, for example, that the tenfold increase [in the population of London] was in the period before the expropriative parliamentary enclosures of Marxist legend, when state fiat was used to deny smaller farmers their ancient, customary rights to use the land near their villages. While the very first of these enclosure acts appeared as early as 1604, parliamentary enclosure only really got going from the mid-eighteenth century. Instead, for the period in question, enclosure happened in a piecemeal way, with the open fields gradually dissolving as farmers exchanged or sold their tiny strips of land, over time amalgamating them into larger, privately controlled plots. With ownership concentrated in fewer and fewer hands, it became relatively easy to gain the unanimity needed to suspend common rights. The process played out in myriad ways all over the country, sometimes with amicable agreement and voluntary exchange, sometimes with ruthless monopolising of the land, with the already-large owners systematically buying out their neighbours. In some cases it involved the consolidation of existing arable land, in others it meant the conversion of forest, heath, marsh, or fen — the traditional “wastes”, to which the poorer villagers might have had various customary rights to gather firewood for fuel, or to graze their cattle, or to hunt for small game — into land that could be used for farming or pasture.

How this process played out all depended on extremely specific, local conditions. But on the whole it was slow — piecemeal enclosure had been happening to varying degrees since at least the fourteenth century. It’s hard to see how such a sporadic and piecemeal process could have led to such consistently and increasingly massive numbers flocking specifically to London. Indeed, the fact that they singled out London as their target suggests that this narrative might have it back-to-front. Some economic historians argue that it was the prospect of higher wages in the ever-growing metropolis that induced farmers to leave the countryside in the first place, selling up or abandoning their plots to those they left behind. Rather than enclosure pushing peasants off the land and into the city, London’s specific pull may instead have thus created the vacuum that allowed the remaining farmers to bring about enclosure. Otherwise, why didn’t the peasants simply flock to any old urban centre? The second-tier cities like Norwich or Bristol or Exeter or Coventry or York would all have been far less dangerous.

Anton Howes, “London the Great”, Age of Invention, 2020-10-20.

January 1, 2021

The Dutch Fleet and the Raid on the Medway

The History Guy: History Deserves to Be Remembered

Published 3 Nov 2018Two of the world’s greatest sea powers compete for control of the world’s shipping lanes. At the height of the Age of Sail, the Dutch fleet makes one of the most daring naval raids in history. The History Guy remembers the raid on the Medway.

This is original content based on research by The History Guy. Images in the Public Domain are carefully selected and provide illustration. As photographs of actual events are sometimes not available, photographs of similar objects and events are used for illustration.

The episode relates events that occurred during a period of conflict. All information is provided within historical context and is intended for educational purposes. Those who do not learn from history are doomed to repeat it.

Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/TheHistoryGuy

The History Guy: History Deserves to Be Remembered is the place to find short snippets of forgotten history from five to fifteen minutes long. If you like history too, this is the channel for you.

Awesome The History Guy merchandise is available at:

teespring.com/stores/the-history-guy#worldhistory #militaryhistory #thehistoryguy

November 15, 2020

London’s wool and cloth trade fuelled massive growth in the city’s population after 1550

In the latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes traces the rise and fall of the late Medieval wool trade and its rebirth largely thanks to an influx of Dutch and Flemish clothmakers fleeing the wars in the Low Countries after 1550:

The Coat of Arms of The Worshipful Company of Woolmen — On a red background, a silver woolpack, with the addition of a crest on a wreath of red and silver bearing two gold flaxed distaffs crossed like a saltire and the wheel of a gold spinning wheel.

The Worshipful Company of Woolmen is one of the Livery Companies in the City of London. It is known to have existed in 1180, making it one of the older Livery Companies of the City. It was officially incorporated in 1522. The Company’s original members were concerned with the winding and selling of wool; presently, a connection is retained by the Company’s support of the wool industry. However, the Company is now primarily a charitable institution.

The Company ranks forty-third in the order of precedence of the Livery Companies. Its motto is Lana Spes Nostra, Latin for Wool Is Our Hope.

Wikipedia.

… it was one thing to be able to reach these new southern markets, and another thing to have something to sell in them. For the shift in the markets for wool cloth exports also required major changes in the kinds of cloth produced. In this regard, London may well have been a direct beneficiary of the 1560s-80s troubles in the Low Countries that had caused Antwerp’s fall, because thousands of skilled Flemish and Dutch clothmakers fled to England. In particular, these refugees brought with them techniques for making much lighter cloths than those generally produced by the English — the so-called “new draperies”, which could find a ready market in the much warmer Mediterranean climes than the traditional, heavy woollen broadcloths.

The introduction of the new draperies was no mere change in style, however. They were almost a completely different kind of product, involving different processes and raw materials. The traditional broadcloths were “woollens”. That is, they were made from especially fine, short, and curly wool fibres — the type that English sheep were especially famous for growing — which were then heavily greased in butter or oil in preparation for carding, whereby the fibres were straightened out and any knots removed (because of all the oil, in the Low Countries the cloths were known as the wet, or greased draperies). The oily, carded wool was then spun into yarn, and typically woven into a broad cloth about four metres wide and over thirty metres long. But it was still far from ready. The cloth had to be put in a large vat of warm water, along with some urine and a particular kind of clay, and was then trodden by foot for a few days, or else repeatedly compacted by water-powered machinery. This process, known as fulling, scoured the cloth of all the grease and shrunk it, compacting the fibres so that they began to interlock and enmesh. Any sign of the cloth being woven thus disappeared, leaving a strong, heavy, and felt-like material that was, as one textile historian puts it, “virtually indestructible”. To finish, it was then stretched with hooks on a frame, to remove any wrinkles and even it out, and then pricked with teasels — napped — to raise any loose fibres, which were then shorn off to leave it with a soft, smooth, sometimes almost silky texture. Woollens may have been made of wool, but they were no woolly jumpers. They were the sort of cloth you might use today to make a thick, heavy and luxuriant jacket, which would last for generations.

Yet this was not the sort of cloth that would sell in the much warmer south. The new draperies, introduced to England by the Flemish and Dutch clothworkers in the mid-sixteenth century, used much lower-quality, coarser, and longer wool. Later generally classed as “worsteds”, after the village of Worstead in Norfolk, they were known in the Low Countries as the dry, or light draperies. They needed no oil, and the long fibres could be combed rather than carded. Nor did they need any fulling, tentering, napping, or shearing. Once woven, the cloth was already strong enough that it could immediately be used. The end product was coarser, and much more prone to wear and tear, but it was also much lighter — just a quarter the weight of a high-quality woollen. And the fact that the weave was still visible provided an avenue for design, with beautiful diamond, lozenge, and other kinds of patterns. The new draperies, which included worsteds and various kinds of slightly heavier worsted-woollen hybrids, as well as mixes with other kinds of fibre like silk, linen, Syrian cotton, or goat hair, thus came in a dazzling number of varieties and names: from tammies or stammets, to rasses, bays, says, stuffs, grograms, hounscots, serges, mockadoes, camlets, buffins, shalloons, sagathies, frisadoes, and bombazines. To escape the charge that the new draperies were too flimsy and would not last, some varieties were even marketed as durances, or perpetuanas.

Curiously, however, while the shift from woollens to worsted saved on the costs of oiling, fulling, and finishing, it was significantly more labour-intensive when it came to spinning — even resulting in a sort of technological reversion. Given the lack of fulling, the strength of the thread mattered a lot more for the cloth’s durability, and the yarn had to be much finer if the cloth was to be light. The spinning thus had to be done with much greater care, which made it slower. Spinners typically gave up using spinning wheels, instead reverting to the old method of using a rock and distaff — a technique that has been used since time immemorial. Albeit slower, the rock and distaff gave them more control over the consistency and strength of the ever-thinner yarn. For the old, woollen drapery, processing a pack of wool into cloth in a week would employ an estimated 35 spinners. For the new, lighter worsted drapery it would take 250. As spinning was almost exclusively done by women, the new draperies provided a massive new source of income for households, as well as allowing many spinsters or widows to support themselves on their own. Indeed, an estimated 75% of all women over the age of 14 might have been employed in spinning to produce the amounts of cloth that England exported and consumed. Some historians even speculate that by allowing women to support themselves without marrying, it may have lowered the national fertility rate.

This spinning, of course, was not done in London. It was largely concentrated in Norfolk, Devon, and the West Riding of Yorkshire. But the new draperies provided employment of another, indirect kind. As a product that was saleable in warmer climes it could be exchanged for direct imports of all sorts of different luxuries, from Moroccan sugar, to Greek currants, American tobacco (imported via Spain), and Asian silks and spices (initially largely imported via the eastern Mediterranean). The English merchants who worked these luxury import trades were overwhelmingly based in London, and had often funded the voyages of exploration and embassies to establish the trades in the first place, putting them in a position to obtain monopoly privileges from the Crown so that they could restrict domestic competition and protect their profits. Unsurprisingly, as they imported everything to London, it also made sense for them to export the new draperies from London too.

Thus, despite losing the concentrating influence of nearby Antwerp, London came to be the principal beneficiary of England’s new and growing import trades, allowing it to grow still further. The city began to carve out a role for itself as Europe’s entrepôt, replacing Antwerp, and competing with Amsterdam, as the place in which all the world’s rarities could be bought (and from which they could increasingly be re-exported). Indeed, English merchants were apparently happy to sell wool cloth at below cost-price in markets like Spain or Turkey — anything to buy the luxury wares that they could monopolise back home.

November 7, 2020

History Summarized: Wales

Overly Sarcastic Productions

Published 6 Nove 2020Wale, Wale, Wale(s), what have we here? I’ll tell you! A look at the oft-forgotten history of Britain’s secret third country Wales, where the population is about 50% bards just by sheer cultural osmosis.

SOURCES & Further Reading: A Concise History of Wales by Jenkins, A History of Wales by Davies

This video was edited by Sophia Ricciardi AKA “Indigo”. https://www.sophiakricci.com/

Our content is intended for teenage audiences and up.

PATREON: https://www.Patreon.com/OSP

PODCAST: https://overlysarcasticpodcast.transi…

DISCORD: https://discord.gg/osp

MERCH LINKS: http://rdbl.co/osp

OUR WEBSITE: https://www.OverlySarcasticProductions.com

Find us on Twitter https://www.Twitter.com/OSPYouTube

Find us on Reddit https://www.Reddit.com/r/OSP/

October 29, 2020

The Legendary Scottish Infill Plane

Rex Krueger

Published 28 Oct 2020Learn about the famous infill planes of Scotland and England. Do they deliver on the hype?

More video and exclusive content: http://www.patreon.com/rexkrueger

Links from this video:

Hans Bruner’s Book on Infills (affiliate): https://amzn.to/3mlwXpj

(It’s $42.00, which is more than I remembered when I called it “reasonably priced.”)

Patrick Leach, renowned tool dealer: http://supertool.com/oldtools.htm

(READ the page and sign up for the email list to see what Patrick is selling. The list comes out on the 1st of each month. I have no affiliation with Patrick and I pay full retail for anything I get from him.)

Mortise and Tenon Magazine: https://www.mortiseandtenonmag.com/

(No affiliation.)Sign up for Fabrication First, my FREE newsletter: http://eepurl.com/gRhEVT

Wood Work for Humans Tool List (affiliate):

*Cutting*

Gyokucho Ryoba Saw: https://amzn.to/2Z5Wmda

Dewalt Panel Saw: https://amzn.to/2HJqGmO

Suizan Dozuki Handsaw: https://amzn.to/3abRyXB

(Winner of the affordable dovetail-saw shootout.)

Spear and Jackson Tenon Saw: https://amzn.to/2zykhs6

(Needs tune-up to work well.)

Crown Tenon Saw: https://amzn.to/3l89Dut

(Works out of the box)

Carving Knife: https://amzn.to/2DkbsnM

Narex True Imperial Chisels: https://amzn.to/2EX4xls

(My favorite affordable new chisels.)

Blue-Handled Marples Chisels: https://amzn.to/2tVJARY

(I use these to make the DIY specialty planes, but I also like them for general work.)*Sharpening*

Honing Guide: https://amzn.to/2TaJEZM

Norton Coarse/Fine Oil Stone: https://amzn.to/36seh2m

Natural Arkansas Fine Oil Stone: https://amzn.to/3irDQmq

Green buffing compound: https://amzn.to/2XuUBE2*Marking and Measuring*

Stockman Knife: https://amzn.to/2Pp4bWP

(For marking and the built-in awl).

Speed Square: https://amzn.to/3gSi6jK

Stanley Marking Knife: https://amzn.to/2Ewrxo3

(Excellent, inexpensive marking knife.)

Blue Kreg measuring jig: https://amzn.to/2QTnKYd

Round-head Protractor: https://amzn.to/37fJ6oz*Drilling*

Forstner Bits: https://amzn.to/3jpBgPl

Spade Bits: https://amzn.to/2U5kvML*Work-Holding*

Orange F Clamps: https://amzn.to/2u3tp4X

Screw Clamp: https://amzn.to/3gCa5i8Get my woodturning book: http://www.rexkrueger.com/book

Follow me on Instagram: @rexkrueger

October 22, 2020

When England “Londonized”

In the latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes looks at changes in urbanization in England from the Middle Ages onward and the astonishing growth of London in particular:

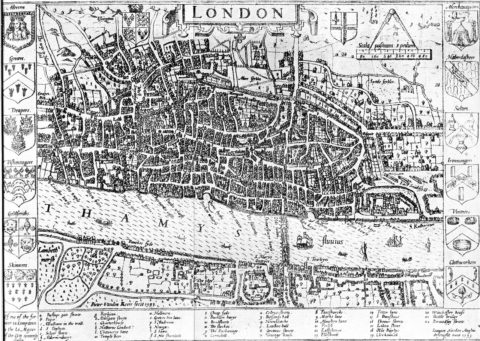

John Norden’s map of London in 1593. There is only one bridge across the Thames, but parts of Southwark on the south bank of the river have been developed.

Wikimedia Commons.

We must thus imagine pre-modern England as a land of tens of thousands of teeny tiny villages, each having no more than a couple of hundred people, which were in turn served by hundreds of slightly larger market towns of no more than a few hundred inhabitants, and with only a handful of regional centres of more than a few thousand people. By the 1550s, the country’s population had still not recovered to its pre-Black Death peak, and still only about 4% of the population lived in cities. London alone accounted for about half of that, with approximately 50-70,000 people (about five times the size of its closest rival, Norwich). So after a couple of centuries of recovery, London was only a little past its medieval peak.

But over the following century and a half, things began to change. At first glance, England’s continued population growth was unremarkable. By 1700, its overall population had finally reached and even surpassed the medieval 5 million barrier, despite the ravages of civil war. This was, perhaps, to be expected, with a little additional agricultural productivity allowing it to surpass the previous record. But the composition of that population had changed radically, largely thanks to the extraordinary growth of London. England’s overall population had not only recovered, but now 16% of them lived in cities of over 5,000 inhabitants — over two thirds of whom lived in London alone. Rather than simply urbanise, England londonised. By 1700, the city was nineteen times the size of second-place Norwich — even though Norwich’s population had more or less tripled.

London had, by 1700, thus risen from obscurity to become one of the largest cities in Europe. At an estimated 575,000 people, it was rivalled in Europe only by Paris and Constantinople, both of which had been massive for centuries. And although by modern standards it was still rather small, it could at least now be comfortably called a city — more or less on par with the populations of modern-day Glasgow or Baltimore or Milwaukee.

During that crucial century and a half then, London almost single-handedly began to urbanise the country. Its eighteenth-century growth was to consolidate its international position, such that by 1800 the city was approaching a million inhabitants, and from the 1820s through to the 1910s was the largest city in the world. In the mid-nineteenth century England also finally overtook Holland in terms of urbanisation rates, as various other cities also came into their own. But this was all just the continuation of the trend. London’s growth from 1550 to 1700 is the phenomenon that I think needs explaining — an achievement made all the more impressive considering how many of its inhabitants were dropping dead.

Throughout that period, urban death rates were so high that it required waves upon waves of newcomers from the countryside to simply keep the population level, let alone increase it. London was ridden with disease, crime, and filth. Not to mention the occasional mass death event. The city lost over 30,000 souls — almost of a fifth of its population — in the plague of 1603 (which was apparently exacerbated by many thousands of people failing to social distance for the coronation of James I), followed by the loss of a fifth again — 41,000 deaths — in the plague of 1625, and another 100,000 deaths — by now almost a quarter of the city’s population — in 1665. And yet, between 1550 and 1700 its population still managed to increase roughly tenfold.

I’ve been hard-pressed to find an earlier, similarly rapid rise to the half-a-million mark that was not just a recovery to a pre-disaster population or simply the result of an empire’s seat of government being moved. Chang’an, Constantinople, Ctesiphon, Agra, Edo, for example — all owed their initial, massive populations to an administrative change (often accompanied by a degree of forcible relocation), and all then grew fairly gradually up to or beyond half a million. As for a very long-term capital like Rome, it seems to have taken about three or four centuries to achieve the increases that London managed in just one and a half (though bear in mind just how rough and ready our estimates of ancient city populations are — our growth guesstimate for Rome is almost entirely based on the fact that the water supply system roughly doubled every century before its supposed peak). The rapidity of London’s rise from obscurity may thus have been unprecedented in human history — and was certainly up there with the fastest growers — though we’ll likely never know for sure.

But how? I can think of a multitude of factors that may have helped it along, but I find that each of them — even when considered altogether — aren’t quite satisfactory.

October 19, 2020

A bowyer talks about authentic longbows

Lindybeige

Published 10 Sep 2016Shot in Visby. I talk to Swedish bowyer Henrik Thurfjell about bows, asking stupid questions so that he sounds comparatively clever.

Support me on Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/LindybeigeHe talks about wood, of hunting, of string, and of bear fat. Many people in the comments have suggested exotic meanings for the mark on the side of the yew bow. The comparatively mundane truth is that the symbol is a combination of the Norse runes for H and T – the bowyer’s initials.

Thanks to Johan Käll for showing me round the re-enactors’ camp.

Picture credits:

By the Mary Rose Trust, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index…

By Mary Rose Trust – Mary Rose Trust, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index…

By Mary Rose Trust – Mary Rose Trust – official webpage, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index…

By Own scan. Photo by Gerry Bye. Original by Anthony Anthony. – Anthony Roll as reproduced in The Anthony Roll of Henry VIII’s Navy: Pepys Library 2991 and British Library Additional MS 22047 With Related Documents ISBN 0-7546-0094-7, p. 42., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index…

By the Mary Rose Trust, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index…

By the Mary Rose Trust, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index…Buy the music – the music played at the end of my videos is now available here: https://lindybeige.bandcamp.com/track…

Lindybeige: a channel of archaeology, ancient and medieval warfare, rants, swing dance, travelogues, evolution, and whatever else occurs to me to make.

▼ Follow me…

Twitter: https://twitter.com/Lindybeige I may have some drivel to contribute to the Twittersphere, plus you get notice of uploads.

website: www.LloydianAspects.co.uk

October 1, 2020

English lead and the European markets of the 1600s

In the latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes considers the meteoric rise in lead production in England and Wales from the dissolution of the monasteries under Henry VIII to the Thirty Years’ War in Europe:

The well-preserved ruins of Fountains Abbey, a Cistercian monastery near Ripon in North Yorkshire. Founded in 1132 and dissolved by order of King Henry VIII in 1539. It is now owned by the Royal Trust as part of Studley Royal Park, a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Photo by Admiralgary via Wikimedia Commons.

In the early sixteenth century, England was a minor producer of the stuff. It was widespread and cheap enough to be used for roofing buildings (unlike much of the rest of Europe, where copper was preferred), but the country never produced more than a few hundred tons per year. It didn’t really need to. Like stone in [the game] Dawn of Man, you could amass a stockpile and not worry too much about any leaky bucket problems [where stockpiles need to be replenished due to wastage or other “drains”]. The lead in roofs could always be recycled, and hardly any more was needed for pipes or cisterns. The vast majority of the demand came from Germany, and then the New World, where it was used to extract silver from copper ore. Even this dissipated in the mid-sixteenth century, when the New World silver mines began to switch to using mercury instead.

Yet by 1600, England was producing about 3,000 tons of lead a year, up from just 300 in the 1560s. By 1700, it was producing two thirds of Europe’s lead — a whopping 20,000 tons a year. How?

Unlike copper or iron, there is no evidence that lead mining or processing techniques were imported. If anything, they seem to have emerged from the Mendips, in Somerset, where production costs fell with the introduction of furnace smelting in the 1540s. As well as raising the extraction rates from the ore coming up from the mines, the new furnaces allowed previously unusable ores — found in the easily-accessible waste tips of old mining camps — to be smelted after some simple sifting. Unfortunately, we don’t have a clear idea of who was responsible for the innovation.

Yet the source of England’s supremacy was really, at first, religious. Following the dissolution of the monasteries by Henry VIII in the 1530s, the melting down of their roofs dumped some 12,000 tons of lead onto England’s markets — at least a year’s worth of Europe’s entire output. Although the immediate effect was to annihilate England’s own lead industry, the medium-term effect was to send the other European producers into disarray. By the 1580s, once the stockpile had depleted, England’s lead producers were among the only ones left standing. The sale of monastic lead ensured that the English retained a foothold in foreign markets, while the cost-saving innovations then gave them the competitive edge. These factors explain, at least, England’s eventual hold over the European lead market.

But there was yet another phenomenon responsible for the industry’s massively increased scale: the development of hand-held firearms. Gunpowder technology was of course centuries old, but cannon had largely fired balls made of stone or cast iron. Muskets and pistols, however, used bullets made of lead. With the proliferation of the weapons over the course of the seventeenth century, lead thus acquired a major leaky bucket problem. Bullets were too costly to recycle, leading to an estimated fifth of Europe’s annual production of lead disappearing every year — a wastage that only increased as armies grew, weapons’ rate of fire improved, and the continent experienced extraordinary violence. Europe lost an estimated fifth of its population to the Thirty Years’ War, and England itself succumbed to civil strife.

England’s lead industry thus had to drastically increase its production just to maintain Europe’s stock of lead, let alone increase it. It was from soldiers entering the fray, to trade bullets across sodden fields, that it owed its extraordinary success.

September 18, 2020

From innovation to absolutism — English inventors and the Divine Right of Kings

In the latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes looks at how innovations during the late Tudor and Stuart eras sometimes bolstered the monarchy in its financial battles with Parliament (which, in turn, eventually led to actual battles during the English Civil War):

King Charles I and Prince Rupert before the Battle of Naseby 14th June 1645 during the English Civil War.

19th century artist unknown, from Wikimedia Commons.

The various schemes that innovators proposed — from finding a northeast passage to China, to starting a brass industry, to colonising Virginia, or boosting the fish industry by importing Dutch salt-making methods — all promised to benefit the public. They were to support the “common weal”, or commonwealth. And to a certain extent, many projects did. The historian Joan Thirsk did much pioneering work in the 1970s to trace the impact of various technological or commercial projects, revealing that even something as mundane as growing woad, for its blue dye, could have a dramatic impact on local economies. With woad, the income of an ordinary farm labouring household might be almost doubled, for four months in the year, by employing women and children. In the late 1580s, the 5,000 or so acres converted to woad-growing in the south of England likely employed about 20,000 people. That may seem small today, but at a time when the population of a typical market town was a paltry 800 people, even a few hundred acres of woad being cultivated here or there might draw in workers from across the whole region. In the mid-sixteenth century, even the entire population of London had only been about 50-70,000. As Thirsk discovered, innovative projectors also sometimes fulfilled their other public-spirited promises, for example by creating domestic substitutes for costly imported goods, or securing the supplies of strategic resources.

But the ideal of benefiting the commonwealth could also, all too frequently, be elided with serving the interests of the Crown. Projectors might promise the monarch a direct share of an invention’s profits, or that a stimulated industry would result in higher income from tariffs or excise taxes. Increasingly, they proposed schemes that were almost entirely focused on maximising state revenue, with little evidence of new technology. They identified “abuses” in certain industries — at this remove, it’s difficult to tell if these justifications were real — and asked for monopolies over them in order to “regulate” them, then making money by selling licences. Last week I mentioned patents over alehouses, and on playing cards. They also offered to increase the income from the Crown’s property, for example by finding so-called “concealed lands” — lands that had been seized during the Reformation, but which through local resistance or corruption had ostensibly not been paying their proper rents. The projectors would take their share of the money they identified as “missing”. And they proposed enforcing laws, especially if the punishments involved levying fines or confiscating property. The projectors offered to find the lawbreakers and prosecute them, after which they’d take their share of the financial punishments.

Projectors thus came to present themselves as state revenue-raisers and enforcers, circumventing all of the traditional constraints on the monarch’s money and power. They provided an alternative to Parliaments, as well as to city corporations and guilds, in raising money and propagating their rule. Taking it a step further, projectors offered the tantalising possibility that kings like James I and Charles I might rule through proclamation and patents alone, without having to answer to anybody. They thus experimented with absolutism for much of 1610-40, only occasionally being forced to call Parliament for as briefly as possible when the pressing financial demands of war intervened.

In the process, with the growing multitude of projects — a few bringing technological advancement, but many merely lining the pockets of courtier and king — the designation “projector” became mud. It was as if, today, the Queen were to use her prerogative to grant a few of her courtiers monopolies on collecting all traffic fines, or litter penalties, to be rewarded solely on commission. Or if she were to award an unscrupulous private company the right to award all alcohol-selling licences (perhaps on the basis that underage drinking was becoming common). The country would soon be awash with hidden speed cameras and incognito litter wardens, and the price of alcohol would go through the roof. The people responsible would not be popular. A recent book by economic historian Koji Yamamoto meticulously charts the changing public perceptions of projects, describing the ways in which innovators then struggled, for decades, to regain the public’s trust.

September 5, 2020

Beginning the transition from personal rule to the modern bureaucratic state

Anton Howes discusses some of the issues late Medieval rulers had which in some ways began the ascendency of our modern nation state with omnipresent bureaucratic oversight of everyone and everything:

… the bureaucratic state of today, with its officials involving themselves with every aspect of modern life, is a relatively recent invention. In a world without bureaucracy, when state capacity was relatively lacking, it’s difficult to see what other options monarchs would have had. Suppose yourself transported to the throne of England in 1500, and crowned monarch. Once you bored of the novelty and luxuries of being head of state, you might become concerned about the lot of the common man and woman. Yet even if you wanted to create a healthcare system, or make education free and universal to all children, or even create a police force (London didn’t get one until 1829, and the rest of the country not til much later), there is absolutely no way you could succeed.

King James I (of England) and VI (of Scotland)

Portrait by Daniel Myrtens, 1621 from the National Portrait Gallery via Wikimedia Commons.For a start, you would struggle to maintain your hold on power. Fund schools you say? Somebody will have to pay. The nobles? Well, try to tax them — in many European states they were exempt from taxation — and you might quickly lose both your throne and your head. And supposing you do manage to tax them, after miraculously stamping out an insurrection without their support, how would you even begin to go about collecting it? There was simply no central government agency capable of raising it. Working out how much people should pay, chasing up non-payers, and even the physical act of collection, not to mention protecting that treasure once collected, all takes substantial manpower. Not to mention the fact that the collecting agents will likely siphon most of it off to line their own pockets.

[…]

It was not until 1689, when there was a coup, that an incoming ruler allowed the English parliament to sit whenever it pleased. Before that, it was convened only at the whim of the ruler, and dispersed even at the slightest provocation. In 1621, for example, when James I was planning to marry his heir to a Spanish princess, Parliament sent him a petition asserting their right to debate the matter. Upon hearing of it, he called for the official record of parliamentary proceedings, personally ripped out the page with the offending vote, and promptly dissolved the Parliament. The downside, of course, was that James could not then acquire any parliamentary subsidies.

Ruling was thus an intensely personal affair, of making deals and finding ways to circumvent deals you had inherited. Increasing your capabilities as a ruler – state capacity – was thus no easy task, as the typical ruler was stuck in an essentially medieval equilibrium. Imposing a policy costs money, but raising money involves imposing policy. Breaking out of this chicken-and-egg problem took centuries of canny leadership. The rulers who achieved it most would today seem hopelessly corrupt.

To gain extra cash without interference from Parliament, successive monarchs first asserted and then abused their ancient prerogative rights to grant monopolies over trades and industries. They eventually granted them to whomever was willing to pay, establishing monopolies over industries like gambling cards or alehouses under the guise of regulating unsavoury activities. They also sold off knighthoods and titles, and in 1670 Charles II even made a secret deal with the French that he would convert to Catholicism and attack the Protestant Dutch, all in exchange for cash. Anything to not have to call a potentially pesky Parliament. At times, the most effective rulers even resembled mob bosses. Take Elizabeth I’s anger when a cloth-laden merchant fleet bound for an Antwerp fair in 1559 was allowed to depart. Her order to stop them had not arrived in time, thus preventing her from extracting “loans” from the merchants while she still had their goods within her power.

September 4, 2020

How England used to vote

Learnhistory3

Published 1 May 2011Rowan Atkinson as Edmund BlackAdder in a sketch on the voting situation before 1832. Rotten boroughs and pocket boroughs etc

Script excerpt from BlackAdder Scripts:

At Mrs. Miggins’ home

E: Well, Mrs. Miggins, at last we can return to sanity. The hustings are

over, the bunting is down, the mad hysteria is at an end. After the

chaos of a general election, we can return to normal.M: Oh, has there been a general election, then, Mr. BlackAdder?

E: Indeed there has, Mrs. Miggins.

M: Oh, well, I never heard about it.

E: Well of course you didn’t; you’re not eligible to vote.

M: Well, why not?

E: Because virtually no-one is: women, peasants, (looks at Baldrick)

chimpanzees (Baldrick looks behind himself, trying to see the animal),

lunatics, Lords…B: That’s not true — Lord Nelson’s got a vote!

E: He’s got a boat, Baldrick. Marvelous thing, democracy. Look at

Manchester: population, 60,000; electoral roll, 3.M: Well, I may have the brain the size of a sultana…

E: Correct…

M: …but it hardly seems fair to me.

E: Of course it’s not fair — and a damn good thing too. Give the like of

Baldrick the vote and we’ll be back to cavorting druids, death by

stoning, and dung for dinner.B: Oh, I’m having dung for dinner tonight.

M: So, who are they electing when they have these elections?

E: Ah, the same old shower: fat tory landowners who get made MPs when

they reach a certain weight; raving revolutionaries who think that just

because they do a day’s work that somehow gives them the right to get

paid… Basically, it’s a right old mess. Toffs at the top, plebs at the

bottom, and me in the middle making a fat pile of cash out of both of them.M: Oh, you’d better watch out, Mr. BlackAdder; things are bound to change.

E: Not while Pitt the Elder’s Prime Minister they aren’t. He’s about as

effective as a catflap in an elephant house. As long as his feet are warm

and he gets a nice cup of milky tea in the sun before his morning nap,

he doesn’t bother anyone until his potty needs emptying.

August 31, 2020

Military Equipment of the Anglo Saxons and Vikings

Invicta

Published 19 Apr 2018Today we dive into the world of Early Medieval England to analyze the military equipment available to the warring Anglo Saxons and Vikings!

Support future documentaries: https://www.patreon.com/InvictaHistory

Twitter: https://twitter.com/InvictaHistoryDocumentary Credits:

Research: Invicta

Script: Invicta

Artwork: Osprey Publishing

Game: Total War Saga: Thrones of Britannia

Editing: Invicta

Music: Total War: Attila and Total War Battles: Kingdoms SoundtrackLiterary Sources

–Anglo-Saxon Thegn by Mark Harrison (Osprey Publishing)

–Viking Hersir 793–1066 AD by Mark Harrison (Osprey Publishing)

–Saxon, Viking and Norman by Terence Wise (Osprey Publishing)