World War Two

Published 2 Dec 2023The bulk of the fight for Hürtgen Forest is now over, and today we look at the results. We also look at Soviet plans for their January offensive. In the field this week, the Red Army is still fighting in Hungary, the Allies are still trying to reach the Roer River in the west, and in the Pacific Theater the kamikaze menace is wreaking havoc with Allied scheduling.

00:00 INTRO

01:06 Soviet Offensive Plans for 1945

03:12 Red Army attacks in Hungary

06:19 The Port of Antwerp is clear for use

07:23 The Battle of Hurtgen Forest is Over

12:20 Allied advances to the Roer

14:19 Tension builds in Greece

15:32 The aerial situation in the Philippines

21:36 CONCLUSION

(more…)

December 3, 2023

Was Hürtgen Forest Worth it? WW2 – Week 275 – December 2, 1944

October 22, 2022

Battle of the Bulge 1944: Could the German Plan Work?

Real Time History

Published 21 Oct 2022Sign up for Nebula and watch Rhineland 45: https://nebula.tv/realtimehistory

The Battle of the Bulge was one of the last German offensives during the Second World War. It caught the US Army off guard in the Ardennes sector but ultimately the Allies prevailed. But did Unternehmen Wacht am Rhein (“Operation Watch on the Rhine”) ever have a chance to succeed and reach Antwerp?

(more…)

May 5, 2022

The Forgotten Battle: The story of the Battle for the Scheldt

Omroep Zeeland

Published 18 Mar 2020Documentary directed by Margot Schotel Omroep Zeeland (2019) about the battle of the Scheldt. An large and important battle in the autumn of 1944, which was crucial for the liberation of the Netherlands and Europe

After D-Day (6 June, 1944), the Allied Forces quickly conquered the north of France and Belgium. Already on 4 September they took Antwerp, a strategically vital harbor. However, the river Scheldt, the harbor’s supply route, was still in German hands. Montgomery was ordered by Eisenhower to secure both sides of the Scheldt, the larger part of which is located in the Netherlands, but Montogomery decided otherwise and started Operation Market Garden. He left the conquest of the Scheldt to the Canadians and the Polish Armies who then had to fight a much stronger enemy that was ordered by Hitler himself to keep its position at all costs. Even though Market Garden eventually failed, it received an almost mythological status in the narrative about the World War II, while the successful battle for the Scheldt was never really acknowledged by history.

With the cooperation of Tobias van Gent, Ingrid Baraitre, Carla Rus, Johan van Doorn ea.

Blijf op de hoogte van het laatste Zeeuwse nieuws:

Volg ons via:

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/omroepzeeland/

Twitter: https://twitter.com/omroepzeeland

Youtube: https://www.youtube.com/c/omroepzeeland

November 17, 2021

The Real History Behind The Forgotten Battle | Battle of Walcheren 1944

History With Hilbert

Published 10 Nov 2021The Forgotten Battle is a Dutch/Belgian Netflix war film set during the Battle of Walcheren in 1944, part of the Liberation of the Netherlands from German control following the successful D-Day landings of the Allies. In this video I look at the history of the Battle of the Scheldt and in particular the assault on Walcheren, as well as some of the other historical aspects covered by the film such as Dutchmen who served in the Waffen SS on the Eastern Front and the Dutch Resistance (De Ondergrondse) who fought against the German occupiers and aided the Allies in their push into the Netherlands.

@History Hustle’s excellent videos on Dutch Waffen SS units:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bQlF0…Go Fund My Windmills (Patreon):

https://www.patreon.com/HistorywithHi…Join in the Banter on Twitter:

https://twitter.com/HistorywHilbertIndulge in some Instagram..?(the alliteration needs to stop):

https://www.instagram.com/historywith…0:00 – Intro

3:00 – Walcheren Remains In German Hands

4:14 – The Battle of Walcheren Causeway

6:18 – Operation Infatuate I & II

8:00 – Walcheren Is Captured

8:47 – Dutchmen Serving in the SS

10:18 – The Dutch Resistance In World War 2

13:04 – OutroSend me an email if you’d be interested in doing a collaboration! historywithhilbert@gmail.com

#WW2 #Netherlands #Netflix

November 15, 2020

London’s wool and cloth trade fuelled massive growth in the city’s population after 1550

In the latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes traces the rise and fall of the late Medieval wool trade and its rebirth largely thanks to an influx of Dutch and Flemish clothmakers fleeing the wars in the Low Countries after 1550:

The Coat of Arms of The Worshipful Company of Woolmen — On a red background, a silver woolpack, with the addition of a crest on a wreath of red and silver bearing two gold flaxed distaffs crossed like a saltire and the wheel of a gold spinning wheel.

The Worshipful Company of Woolmen is one of the Livery Companies in the City of London. It is known to have existed in 1180, making it one of the older Livery Companies of the City. It was officially incorporated in 1522. The Company’s original members were concerned with the winding and selling of wool; presently, a connection is retained by the Company’s support of the wool industry. However, the Company is now primarily a charitable institution.

The Company ranks forty-third in the order of precedence of the Livery Companies. Its motto is Lana Spes Nostra, Latin for Wool Is Our Hope.

Wikipedia.

… it was one thing to be able to reach these new southern markets, and another thing to have something to sell in them. For the shift in the markets for wool cloth exports also required major changes in the kinds of cloth produced. In this regard, London may well have been a direct beneficiary of the 1560s-80s troubles in the Low Countries that had caused Antwerp’s fall, because thousands of skilled Flemish and Dutch clothmakers fled to England. In particular, these refugees brought with them techniques for making much lighter cloths than those generally produced by the English — the so-called “new draperies”, which could find a ready market in the much warmer Mediterranean climes than the traditional, heavy woollen broadcloths.

The introduction of the new draperies was no mere change in style, however. They were almost a completely different kind of product, involving different processes and raw materials. The traditional broadcloths were “woollens”. That is, they were made from especially fine, short, and curly wool fibres — the type that English sheep were especially famous for growing — which were then heavily greased in butter or oil in preparation for carding, whereby the fibres were straightened out and any knots removed (because of all the oil, in the Low Countries the cloths were known as the wet, or greased draperies). The oily, carded wool was then spun into yarn, and typically woven into a broad cloth about four metres wide and over thirty metres long. But it was still far from ready. The cloth had to be put in a large vat of warm water, along with some urine and a particular kind of clay, and was then trodden by foot for a few days, or else repeatedly compacted by water-powered machinery. This process, known as fulling, scoured the cloth of all the grease and shrunk it, compacting the fibres so that they began to interlock and enmesh. Any sign of the cloth being woven thus disappeared, leaving a strong, heavy, and felt-like material that was, as one textile historian puts it, “virtually indestructible”. To finish, it was then stretched with hooks on a frame, to remove any wrinkles and even it out, and then pricked with teasels — napped — to raise any loose fibres, which were then shorn off to leave it with a soft, smooth, sometimes almost silky texture. Woollens may have been made of wool, but they were no woolly jumpers. They were the sort of cloth you might use today to make a thick, heavy and luxuriant jacket, which would last for generations.

Yet this was not the sort of cloth that would sell in the much warmer south. The new draperies, introduced to England by the Flemish and Dutch clothworkers in the mid-sixteenth century, used much lower-quality, coarser, and longer wool. Later generally classed as “worsteds”, after the village of Worstead in Norfolk, they were known in the Low Countries as the dry, or light draperies. They needed no oil, and the long fibres could be combed rather than carded. Nor did they need any fulling, tentering, napping, or shearing. Once woven, the cloth was already strong enough that it could immediately be used. The end product was coarser, and much more prone to wear and tear, but it was also much lighter — just a quarter the weight of a high-quality woollen. And the fact that the weave was still visible provided an avenue for design, with beautiful diamond, lozenge, and other kinds of patterns. The new draperies, which included worsteds and various kinds of slightly heavier worsted-woollen hybrids, as well as mixes with other kinds of fibre like silk, linen, Syrian cotton, or goat hair, thus came in a dazzling number of varieties and names: from tammies or stammets, to rasses, bays, says, stuffs, grograms, hounscots, serges, mockadoes, camlets, buffins, shalloons, sagathies, frisadoes, and bombazines. To escape the charge that the new draperies were too flimsy and would not last, some varieties were even marketed as durances, or perpetuanas.

Curiously, however, while the shift from woollens to worsted saved on the costs of oiling, fulling, and finishing, it was significantly more labour-intensive when it came to spinning — even resulting in a sort of technological reversion. Given the lack of fulling, the strength of the thread mattered a lot more for the cloth’s durability, and the yarn had to be much finer if the cloth was to be light. The spinning thus had to be done with much greater care, which made it slower. Spinners typically gave up using spinning wheels, instead reverting to the old method of using a rock and distaff — a technique that has been used since time immemorial. Albeit slower, the rock and distaff gave them more control over the consistency and strength of the ever-thinner yarn. For the old, woollen drapery, processing a pack of wool into cloth in a week would employ an estimated 35 spinners. For the new, lighter worsted drapery it would take 250. As spinning was almost exclusively done by women, the new draperies provided a massive new source of income for households, as well as allowing many spinsters or widows to support themselves on their own. Indeed, an estimated 75% of all women over the age of 14 might have been employed in spinning to produce the amounts of cloth that England exported and consumed. Some historians even speculate that by allowing women to support themselves without marrying, it may have lowered the national fertility rate.

This spinning, of course, was not done in London. It was largely concentrated in Norfolk, Devon, and the West Riding of Yorkshire. But the new draperies provided employment of another, indirect kind. As a product that was saleable in warmer climes it could be exchanged for direct imports of all sorts of different luxuries, from Moroccan sugar, to Greek currants, American tobacco (imported via Spain), and Asian silks and spices (initially largely imported via the eastern Mediterranean). The English merchants who worked these luxury import trades were overwhelmingly based in London, and had often funded the voyages of exploration and embassies to establish the trades in the first place, putting them in a position to obtain monopoly privileges from the Crown so that they could restrict domestic competition and protect their profits. Unsurprisingly, as they imported everything to London, it also made sense for them to export the new draperies from London too.

Thus, despite losing the concentrating influence of nearby Antwerp, London came to be the principal beneficiary of England’s new and growing import trades, allowing it to grow still further. The city began to carve out a role for itself as Europe’s entrepôt, replacing Antwerp, and competing with Amsterdam, as the place in which all the world’s rarities could be bought (and from which they could increasingly be re-exported). Indeed, English merchants were apparently happy to sell wool cloth at below cost-price in markets like Spain or Turkey — anything to buy the luxury wares that they could monopolise back home.

November 29, 2019

England’s early search for new markets

In the latest installment of Anton Howes’ Age of Invention, he looks at the multiple crises that afflicted England in the mid-sixteenth century and some of the reactions to those setbacks:

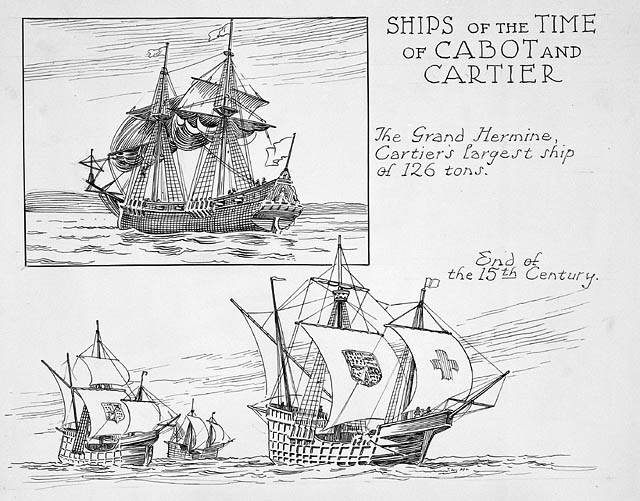

Ships from the period of John Cabot (Giovanni Caboto) and Jacques Cartier.

Illustration by Thomas Wesley McLean (1881-1951) via Wikimedia Commons.

From the 1540s through to the 1560s, [England] was beset by religious uproar, high inflation, hunger, rural and then urban unemployment, a fall-off in its major export trades, and widespread unrest. It was diplomatically isolated too. And I did not even mention the epidemics: the terrifying “sweating sickness” returned in 1551, deadly influenza swept the country in 1557, and in 1563 some 17,000 people in London were reportedly killed by the plague.

Yet, in the face of such problems, innovation in England began to pick up pace. The country, having once been a scientific and technological backwater, began to show signs of catching up. Why?

[…] The fall-off in trade with Europe, for example, seems to have had something to do with spurring the voyages of exploration in search of a north-west and north-east passage to the East Asia. Having lost Antwerp as a place to sell cloth in 1551, the English went in search of an arctic route to northern China and Japan. The expert geographers believed that those regions had a similar climate to that of Antwerp and the surrounding Netherlands, and so reasoned that the Japanese would therefore demand the same kinds of cloth. Although the English expeditions from 1553 onwards did not find a passage to Japan, they did establish trade routes with Russia via the White Sea, and they began to more actively consider the exploration and colonisation of North America. More importantly, with those voyages of exploration came greater experience of navigation, and it was not long before English ships were circumnavigating the globe (Francis Drake in 1577-80). Improvements to navigational techniques and instruments, as well as the ships themselves followed.

So it is tempting to think that necessity was initially the mother of invention, and that the many navigational and shipbuilding improvements of late-sixteenth-century England were its result. But I don’t think that this narrative quite works. I do not believe that necessity was the mother of invention.

For a start, voyages of navigation had already been attempted a number of times, long before the more successful ones in the early 1550s. The first explorers had reputedly gone west from Bristol in 1465, and certainly from 1480. And soon after the announcement of Columbus’s discoveries in the 1490s, the Venetian Zuan Chabotto (aka John Cabot), had sailed from Bristol with Henry VII’s blessing and claimed Newfoundland for both crown and Catholicism. Cabot had even hoped to found a penal colony on his second voyage in 1497, though for some reason the king did not provide the criminals. Throughout the early sixteenth century, the voyages continued. John Rastell, brother-in-law to Thomas More, the famous statesman and author of Utopia, in 1517 went in search of a north-west passage (though he never got beyond Ireland, because his crew decided it would be better to leave him there and sell the ship’s cargo in Bordeaux). Yet another voyage went west with Henry VIII’s support in 1527, but it mostly just found other Europeans — fishing fleets from Spain, Portugal, and France off the coast of Newfoundland (the English had made some catches there in the early 1500s, but apparently could not compete), and the Spanish everywhere else. The expedition made its way down to the Caribbean and then went home, with little to report. So people had already gone off exploring, long before the mid-sixteenth-century English commercial crisis. It suggests that there had already been both a latent supply and demand for such explorations.

February 4, 2014

“Chateau” generals

Nigel Davies has written a long post about the British and American standard of generalship in the two world wars, which won’t win him very many American (or Canadian) fans. That being said, he’s certainly right about the Canadian generals of WW2:

Contention: American senior generals in World War II were as bad, and for the same reason, as British senior generals in World War I.

[…] the politicians (and I will include Kitchener here, as he was by this time a politician with a military background rather than a real general), had based their recruiting campaign on a trendy ‘new model’ citizens army, rather than use the well developed existing territorial reserve system that would have done a far better job. They new enthusiastic troops were considered incapable of the traditional fire and movement approach of professional troops (the type that the Germans reintroduced in 1918 with their ‘commando units’, and the British army was able to copy soon after with properly trained and combat experienced personnel). Instead the enthusiastic amateurs were considered too badly trained to do more than advance in long straight lines… straight into the meat grinder.

Having said that the generals blame for the results should be at the very least shared with their political masters, I am still willing to express dissatisfaction with the approach of Haig and many of his senior commanders. They were Chateau Generals in approach and in attitude. They drew lines on maps without adequately considering the terrain, issued impossible instructions without looking at the state of the ground, and ran completely inadequate communications that were far from capable of keeping track of, or controlling, a modern battlefield.

[…]

It was noticeable later in the war that the more successful armies were commanded by competent and imaginative officers who insisted on detailed planning; intensive and specific tactical planning and operational training (down to practicing assaults on purpose built life size models); and very close control of operations to ensure success. They had usually learned the hard way, and had matured as experienced and pro-active leaders.

Of course some of this improvement was simply advances in technology. Tanks to breakthrough; better artillery fire plans to support and reduce casualties; air observation to enhance control and assess responses; better communications (including radio’s) to facilitate flexibility on the ground; and a generally better trained and more experienced soldier; with much more skilled officers. It all helped. But a lot came down to the attitude of the generals who believed that you got up front, found out the truth, stayed in close contact, and reacted to changed circumstances as immediately as possible.

However, as the American army was late to the battlefront, Davies contends that the leaders merely recapitulated the first stages of the bloody learning experience as their British counterparts, but didn’t produce the innovative leadership to match the Germans:

The Americans arrived on the Western Front when the war was already won. Only a few thousand were there for the last big German push, and by the time the Allies were moving to their final offensives with real American numbers involved, the German army was a broken reed. Which means that most American officers had only a few weeks of combat experience, and almost all of it against a failing army which had little resilience left to offer the type of resistance that might have caused the inexperienced American officers to have to reconsider their theories from their quicky officer training courses. Even the professional military officers received, at best, only a couple of hints that their ideas might not be inevitably effective against a stronger opponent. Certainly not enough time to learn how to analyse and adapt to circumstances in serious combat.

Which is why the majority of highly recognised American higher commanders in World War II appear to be chateau generals.

[…]

Eisenhower’s mistakes in theatre commands in Italy and France were possibly no worse in results than Wilson’s ongoing problems with Greece (he led the ‘forlorn hopes’ of both 1941 and 1944 there), but Eisenhower failed far more spectacularly with the Italian surrender, the Broad Front strategy, and the Bulge, than Wilson ever did with far inferior resources. MacArthur’s failures are more readily compared with Percival than the successes of a man like Leese, and Nimitz is often referred to as one of the great captains of history, for defeating a navy that repeatedly sabotaged its own efforts in the Pacific theatre. (Often by people who haven’t seemed to have ever heard of Max Horton’s much harder victory against the ruthlessly efficient U-boat campaign in the Atlantic theatre).

Similarly it is fair to say that the American front line commanders most people have never heard of were hardly inferior to their famous British contemporaries. Eichelberger was as good a commander, and as good a co-operator in Allied operations, as Alexander ever was. Truscott was probably at least the equal of Montgomery, given the opportunity. (I suspect possibly even better actually, but who can say?) Simpson, in his brief few months at the front, impressed many British officers who had served for years under men as good as Slim. And Ridgway showed in his few months of active operations a level of skill and competence (not necessarily the same thing) that far more experienced men like O’Connor did not surpass.

Why do we hear about the American chateau generals in preference to their front line leaders? And why do we hear about the British front line leaders in preference to their back office superiors. I would say it is because the British had been through a learning process in WWI that the Americans had not.

And the Canadian angle? As I’ve noted before, the First Canadian Army (scroll down to the item on John A. English’s book) was not as combat-effective in WW2 as the Canadian Corps had been in the First World War. One of the most obvious failings was in the advance to Antwerp:

Note that the equivalent British debacle during that campaign was when the Canadian Army took Antwerp undamaged, but then stopped for a rest before cutting off the retreating Germans. The Germans quickly fortified the riverbanks leading to the port, keeping it out of use for months. This was a clear example of the Canadian generals inexperience, and Montgomery is at fault here for being too involved in the last attempt to break the Germans before Christmas — Market Garden — and not paying close enough attention to one of his Army commanders, who was not supervising his Corps commander, who was not chasing his divisional commander adequately. (No one is imune from such glitches in a fast moving campaign. Inexperience any where down the chain can cause big problems. But it is noticeable that Crerar’s failure did not get him the public acclaim Patton has enjoyed?) Crerar was a ‘political appointment’ by the Canadians (an ‘able administrator’, but militarily ‘mediocre’ according to most) who Montgomery considered to be as inferior in experience and attitude as many of the American ‘chateau leaders’ he would have put in the same basket. By contrast Monty was delighted when the more competent front line leaders – the Canadian Simonds and the American Simpson – were assigned to him instead. As in the cases of the Australian General Morshead or the Polish General Anders, Montgomery only cared about ability, not nationality. But as was the case with the Americans, all too many generals in most armies, including the British and German armies, lacked experience or ability.

Update, 13 February: Mark Collins linked to an earlier post that helpfully describes some of the problems with Canadian generalship in Europe:

The Canadian command style in WW II was even more stuck in the mud than the American. With a few exceptions (McNaughton, Burns, Crerar) most Canadian generals had little or no General Staff experience, and those that did were practitioners of a successful, for the earlier WW I time and place, doctrine based on set piece battles founded on the systematic and intensive use of artillery.

One virtue of the German system is that it allowed officers to make mistakes: it did not allow them to sit on their butts waiting for orders; it encouraged risk taking which often worked but sometimes ended in bloody disaster (indeed it’s amazing it didn’t in France in 1940).

Indeed comparing the Canadian Army in WWII with the German is very difficult. Both had to expand from a tiny base to their war-time peak, but the Germans began in 1933 (actually even before then); we didn’t really begin until 1940. The Germans lost the Great War and the Reichswehr gave serious thought to how to do better next time.

One thing underlying the British set piece battle approach and limited freedom for commanders – the one the Canadian Army followed – seems to have been their realization in the late 1930s that the British Army was simply not as good as its 1914 ancestor. That was partly because of the losses of promising junior officers who never made general [though that affected the Germans too], partly because of indifference to defence at the governmental level, and partly because the military lapsed all too happily back into “real soldiering” in the 20’s.

September 15, 2011

Belgium “without a government may be remembered as an economic and political golden age”

Doug Saunders looks at the situation in Belgium, which has gone without a government for over 450 days so far:

To look around the elegant city of Antwerp, you wouldn’t know that Belgium has now gone longer without a government than any country in modern history.

The trains still run on time, the teachers show up in their classrooms, museums are packed, taxes are collected, welfare is paid, and the country’s F-16 fighter jets are dropping bombs in Libya — even though Belgium has now gone a year and a quarter without a federal government, after the June 13, 2010 elections produced no majority and the feuding parties became locked in perpetual disagreement over coalition plans.

[. . .]

For some, this might sound like a libertarian’s idea of utopia: A country with nobody to raise taxes, or to slash spending, or to introduce major new government programs.

And indeed, Belgium has just managed, despite having only a largely powerless caretaker government, to post second-quarter economic growth rates — of 0.7 per cent — that exceeded neighbouring Germany, France and Britain. The country’s world-leading beer industry, analysts say, has remained aloft as the world drinks away its financial sorrows. And the government deficit has even been cut somewhat.

Well, it’s rather short of an anarchist’s utopia, but it’s a bit closer to a minarchist’s version. The “government” in question is, of course, the political one: the bureaucracy is still ticking over as before (one wonders if they’ve noticed the lack of politicians and their sometimes malign influence over the everyday activities of the bureaucracy).

It should be no surprise that the lack of new political initiatives has had a moderating influence on the business environment: it has reduced some of the “normal” instability of government activity. The European market and the world markets are still providing sufficient distortion and uncertainty, of course, but at least for some businesses they are not having to make business decisions with a wary eye on the current prime minister’s whim.