George Bailey, the hero of It’s a Wonderful Life, missed the two events that made the ideal man of his time, place, and social class: going to college and serving (as an officer, of course) in the Second World War. Instead of doing those things, either of which would have sent him out into the world beyond the limits of Bedford Falls, he remained at home, taking care of his family, his business, and his community. In other words, the hero of America’s favorite exercise in Yuletide nostalgia epitomized a way of life that, in the season of the film’s cinematic debut (the summer of 1946), was already on its way to the dustbin of history.

This, the most enduring of the many works of Frank Capra, became the Atlantis myth of post-war America. That is, those who, over the course of the last half-century, saw It’s a Wonderful Life on television, knew well that the age of community and connection depicted on their screens had already passed into the realm of legend. Moreover, to add injury to insult, they also knew that, if they wished to enjoy the fruits of a middle-class existence, they would have to live in the manner of vagabonds.

In the movie, slum-lord Henry Potter tries, but fails, to turn the provincial paradise of Bedford Falls into a run-down haunt of spinsters, drunks, and floozies. In the real world, it was Franklin D. Roosevelt who put the kibosh on the original Main Street, USA. To be more precise, the principal achievements of America’s greatest tyrant, the Great Depression and the Second World War, undermined the financial, legal, and cultural foundations of the “wonderful life”. Thus, by the time this process had run its course, inflation had made a fool’s game of simple thrift, the replacement of law with regulation had hobbled private enterprise, and people who had left home for the sake of college, work, or military service found themselves lost in a sea of strangers.

In response to these changes, colleges and universities stepped up to the proverbial plate, happy to offer substitutes for the things that had been lost. They gave young people a chance to obtain certificates that would attest to both their suitability for service in the ranks of corporate minions and their social respectability. At the same time, these institutions gave older people a way to convert their value-losing cash into an asset that promised to pay dividends that would benefit their children (and, indeed, their grandchildren) for decades to come.

Thus arose the people I have come to call the MICE (Mobile, Individualistic, College Educated) people. Bereft of regional accents, productive property, and deep connections to friends and relations, they wandered the world, building networks, acquiring degrees, and padding resumés. However, after two generations of such peripatetic solipsism, the age of the MICE people is coming to an end.

Young men of parts, who realize that college has nothing to do with either liberal learning or vocational training, are simultaneously taking up skilled trades and stocking their MP3 players with learned podcasts. At the same time, young women of quality are beginning to think that the traditional troika of Kirche, Küche, und Kinder offers better odds of deep satisfaction than life as a hormone-hobbled, Starbucks swilling, girl boss.

So, if you know young people like the ones I’ve just described, do posterity a favor, and put them in contact with each other. After all, they deserve a life as wonderful as that of George and Mary Bailey.

Bruce Ivar Gudmundsson, “College, Class, and Christmas”, Extra Muros, 2023-08-06.

December 24, 2023

QotD: Dreaming of George Bailey’s world while living in Pottersville

December 22, 2023

QotD: Mathematically inclined people

I’ve often said that mathematically inclined people generally get that way because God takes everything in their skulls and pushes it over to the left. Tensor calculus? No problem. Understanding that it’s disturbing for a grown man to speak Klingon? Sorry, the part of the brain that ordinarily handles that is busy thinking about the Pauli Exclusion Principle.

Steve H., “Star Wars Still Sucks: ‘Quick, Someone Put More Minwax on Natalie'”, Hog on Ice, 2005-05-26.

December 15, 2023

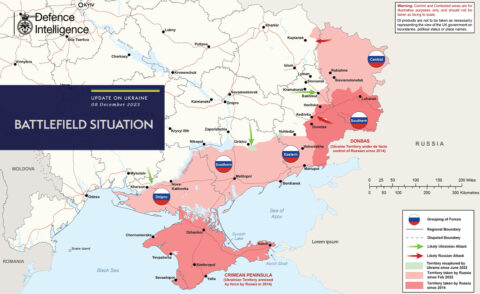

How far are we from a final communiqué from Kiev saying that “the war situation has developed not necessarily to Ukraine’s advantage”?

Yeah, I stole the idea for the headline from Severian’s post from a few days ago. So sue me. But seriously, CDR Salamander considers what he calls the cold truth of the Russo-Ukrainian war:

Well, history didn’t fold out as the Russians wanted. There was no 3-day war. No 3-week war. No 3-month war either. Kiev remains in Ukrainian hands … but what about a 3-year war?

Despite all the pre-war metrics, the “expertise” of the Smartest People in the Room™, every wargame that would have been run at all our war colleges would have told us that there would not be a conventional war in Ukraine is finishing up its second and going in to its third year, but here we are.

They were all wrong.

A common problem, one that well pre-dates the invasion of Ukraine, is that we have shockingly well credentialed people of influence from both parties who have an inability to understand that Russians are not Westerners. They don’t think like Westerners, though they may look like them.

The Russians have a distinct culture, history, and view of themselves and their place in history. The underperforming political, military, and diplomatic elite in the West — with few exceptions outside the former Warsaw Pact nations now in NATO — expect Russians to react in the same way and to the same degree to the incentives and disincentives that move needles and preferences in DC and Brussels.

Time is always on the side of Russia, which is one of the reasons the slow rolling of weapons to Ukraine has been an exercise of malpractice of the highest degree. You are either in or out.

Two years on, “we” still are not sending a clear signal. It is amazing, really; in military might, GDP, demographics and a whole host of other reasons, Russia should not be as resilient as they are … which is why DC & Brussels are being played so hard. They still do not understand Russia.

Even after 1,000 years of experience, we have Western leaders who refuse to believe that the Russians are fundamentally different than the West is in the 21st Century. You can’t put the cultural ability to absorb damage and brutal patience you cannot see in some metric that can go on a PPT slide.

What the Russians lack in so many other places, they make up for here. As such, this critical part of understanding Russian motivation keeps being missed. Yes to their economy and apocalyptic demographics. Yes to all that.

For all the reasons Russia continues to fight, so too do their Ukrainian brothers – demonstrating greater resilience and endurance that Western expectations.

The time for leaving Ukraine to its fate is long past. Yes, the West has a short attention span and is suffering under the dead hand of entrenched leaders with a defeatist mindset – but none of this is written.

Ukraine can still win – or at least something that can be called a win. It would help if the Russians had some internal issues that required more attention that Ukraine, but even then – all is not worth shrugging over.

Yes, I’ve seen the math — the metrics — but war is informed by math, but not defined within it.

At a relatively modest cost in our treasure and almost none of our blood, we are wearing down Russia’s ability to project power for a generation, perhaps two. Perhaps many more generations should demographic instability mate with political instability. The Ukrainians – facing the same economic and demographic challenges as the Russians – are up for the fight. There is no reason for more comfortable nations who have supported them so far to go wobbly at half-time.

Of course, as noted yesterday, this ship may already have sailed thanks to Hamas.

December 14, 2023

December 11, 2023

Roman glossary

As I continue to post QotD entries drawn from Bret Devereaux’s fascinating historical blog A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry (with Dr. Devereaux’s kind permission, I hasten to add), the number of specialized terms from the Roman Republic and Empire also expands. As some of these terms pop up in my shorter excerpts without immediate context, I think that a glossary for Rome is called for (similar to the Spartan glossary, as there’s a lot more Roman content coming up, it being Dr. Devereaux’s area of academic specialization) to help explain the terms that I think may need expansion in these excerpts from his longer posts. As usual, most of the information is drawn directly from ACOUP (often from more than one original post) and where I’ve felt the need to interpolate any additional information it will be enclosed in square brackets. Errors and misinterpretations of his original work are purely mine.

December 9, 2023

The coming Micro-Macro culture war … and who’s going to win it

Ted Gioia outlines the dismal state of the “macro” culture — television, movies, newspapers, book publishing and all the big corporations that control them — with the dynamism of the “micro” culture:

In the beginning, all culture was microculture.

You knew what was happening in your tribe or village. But your knowledge of the wider world was limited.

So you had your own songs and your own stories. You had your own rituals and traditions. You even had your own language.

But all these familiar things disappeared when you went off into the world. That was dangerous, however. That’s why only heroes, in traditional stories, go on journeys.

You learn on the journey. But you might not survive.

But all that changed long before I was born.

In my childhood, everything was controlled by a monoculture. There were only three national TV networks, but they were pretty much the same.

When I went to the office, back then, we had all watched the same thing on TV the night before. We had all seen the same movie the previous weekend. We had all heard the same song on the radio while driving to work.

The TV shows were so similar that they sometimes moved from CBS to NBC, and you never noticed a change. The newscasters also looked pretty much the same and always talked the same — with that flat Midwestern accent that broadcasters always adopted in the US.

The same monoculture controlled every other creative idiom. Six major studios dominated the film business. And just as Hollywood controlled movies, New York set the rules in publishing. Everything from Broadway musicals to comic books was similarly concentrated and centralized.

The newspaper business was still local, but most cities had 2 or 3 daily newspapers — and much of the coverage they offered was interchangeable. Radio was a little more freewheeling, but eventually deregulation allowed huge corporations to acquire and standardize what happened over the airwaves. [NR: I suspect the “freewheeling” went away once the government started imposing regulations, and the corporate consolidation was enabled when they “deregulated” the radio licensing regime several decades later.]

When I went to work in an office, back then, we had all watched the same thing on TV the night before. We had all seen the same movie the previous weekend. We had all heard the same song on the radio while driving to work.

And that’s why smart people back then paid attention to the counterculture.

The counterculture might be crazy or foolish or even boring. But it was still your only chance to break out of the monolithic macroculture.

Many of the art films I saw at the indie cinema were awful. But I still kept coming back — because I needed the fresh air these oddball movies provided. For the same reason, I read the alt weekly newspapers and kept tabs on alt music.

In fact, whenever I saw the word alt, I paid attention.

That doesn’t mean that I hated the major TV networks, or the large daily newspaper, or 20th Century Fox. But I craved access to creative and investigative work that hadn’t been approved by people in suits working for large organizations.

The Internet should have changed all this. And it did — but not much. Even now the collapse in the monoculture is still in its early stages.

But that’s about to change.

If you don’t pay close attention, the media landscape seems pretty much the same now as it did in the 1990s. The movie business is still controlled in Hollywood. The publishing business is still controlled in New York. The radio stations are still controlled by a few large companies. And instead of three national TV networks plus PBS, we have four dominant streaming platforms — who control almost 70% of the market.

So we still live in a macro culture. But it feels increasingly claustrophobic. Or even worse, it feels dead.

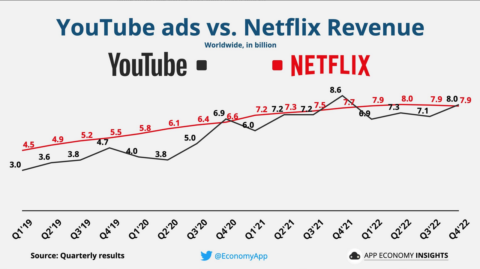

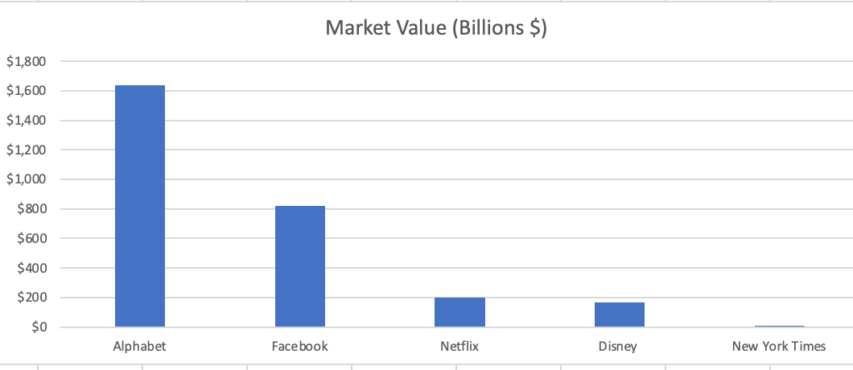

Meanwhile, a handful of Silicon Valley platforms (Google, Facebook, etc.) have become more powerful than the New York Times or Hollywood studios or even Netflix. It’s not even close — the market capitalization of Google’s parent Alphabet is now almost ten times larger than Disney’s.

But here’s the key point — these huge tech companies rely on the microculture for their dominance.

Where is Facebook without users contributing photos, text and video? Where is Google’s YouTube without individual creators?

In terms of economic growth or audience capture, the microculture has already won the war. But it doesn’t feel that way.

Why not?

First and foremost, Silicon Valley is a reluctant home for the microculture. To some extent Alphabet and Facebook are even going to war with microculture creators — they try to make money with them even while they punish them.

- So Mark Zuckerberg needs creators, but won’t even let them put a live link on Instagram and limits their visibility on Facebook and Threads.

- Alphabet needs creators to keep YouTube thriving, but gives better search engine visibility to total garbage that pays for placement.

- Twitter also claims it wants to support independent journalists — but if you’re truly independent from Elon Musk, your links are brutally punished by the algorithm.

This tension won’t go away, and next year it will get worse. The microculture will increasingly find itself at war with the same platforms they rely on today.

And legacy media and non-profits are even more hostile to emerging media. Go see who wins Pulitzer Prizes, and count how many journalists on alternative platforms get honored.

I’ll save you the trouble. They don’t.

December 8, 2023

“When you see the same signs here that characterised collapse in other polities for the last 5000 years, it means collapse is coming here too – we’re not special snowflakes”

Feeling good? Happy with your culture and comfortable that major disruptions won’t disturb you? Here’s Theophilus Chilton to harsh your mellow:

There are essentially three basic reasons why those on the American Right haven’t shrugged the same way regular folks in Europe are beginning to (see Spain and France as well as Ireland for recent examples). The first of these is because the American Right still holds onto a residual trust in elections and democracy and the whole “We’ll get ‘em next election!” mentality. Having been fed a decades-long diet of reverence for democracy and voting and whatnot acts as a desensitising agent that keeps many Americans anesthetised to the actual uselessness of such attitudes.

But this will continue to erode as we see more obvious election fraud. Eventually, when the norm becomes “go to bed with the right-wing candidate ahead by 10% and wake up with the left-wing candidate winning by 0.5%,” elections will lose what legitimacy they have left. Further, as “democracy” comes to be increasingly defined as “whatever the Regime wants to do“, more and more normies will start to clue in to the fact that democratic forms are not going to save America, but are in fact what are destroying it.

Second, Heritage Americans and those on the normie Right tend to assume that everybody still plays by the old, traditional set of norms, including FedGov. This “seemed” plausible when the Regime employed incrementalism to gradually acculturate normies to its agenda. But as they accelerate their revolutionary overthrow of everything that normies thought would be sacrosanct like they have over the past few years, this sense of “norms” will go away. And when that happens, there will be a whole lot of people suddenly open to the possibility that something else might become a new set of norms.

Third, because America is so BIG – especially in the geographical sense – Heritage Americans have been able to self-mitigate many of the worse aspects of the Regime agenda. They could get away from the slums. Federalism allowed them to find states in which to prosper despite the Regime’s efforts. And so forth. Regular folks in many places could still plausibly think America was a high trust, high social cohesion society because where they were at locally might well have been. But as the Regime accelerates, this also will stop. $oros DAs will continue to release violent criminals while punishing law-abiding citizens for defending themselves and their property. Immigration and inflation will further erode the economic prosperity that still remains, which is something that fleeing to a Red state can’t fix. And of course, it will all be brought home starkly once 20,000 or so Palestinian “refugees” get relocated into their counties.

Let’s remember that this is what we actually saw in Ireland. Even into the Oughts, Ireland was homogenous, relatively high IQ and high trust, was the Celtic Tiger with lots of prosperity. Then globohomo decided that Ireland needed tons of “refugees” just like the rest of Europe and suddenly that prosperity and safety and high trust went away. What was the response? Riots and continued disorder that Regime attempts to clamp down on are only going to make worse.

This is going to wear out eventually, which is something that FedGov knows. That’s why they’ve been ramping up gun control efforts over the past few years despite constant opposition from the courts. They’re merely trying to prepare for the inevitable by disarming the people they know they need to suppress the most. Unlike most Euro and Anglosphere countries, Americans haven’t allowed themselves to be disarmed — and that’s something that really does vex The Powers That Be.

But the problem is that it isn’t the 1950s anymore, or even the 1990s for that matter. Back in the 1950s, FedGov could literally stick bayonets at the backs of high school students and force unwilling southern states to integrate their schools. Even in the 1990s FedGov could send its agents to besiege and murder dozens of men, women, and children and most people even at an official level wouldn’t say a thing. But now its 2023 and we’re quite a bit further along the decentralisation path in our secular collapse phase. What FedGov had the moral legitimacy and competency to pull off back then isn’t guaranteed for them now anymore.

So what happens when the FBI wants to do another Waco? What happens if Texas decides it doesn’t want to allow the FBI to do another Waco? We’re past the point where we can blithely say, “Well, the Feds can just make Texas go along with it!” Our place in our collapse cycle means that’s not going to fly like it could have 30 years ago.

At this point, the goal should not be to calm people down but to get them riled up so that when (not if) the break comes, it will be so widespread and numerous that it will completely overwhelm the ability of FedGov and its agencies to deal with it. In this vein, I think of Solzhenitsin’s quote from Gulag Archipelago,

And how we burned in the camps later, thinking: What would things have been like if every Security operative, when he went out at night to make an arrest, had been uncertain whether he would return alive and had to say good-bye to his family? Or if, during periods of mass arrests, as for example in Leningrad, when they arrested a quarter of the entire city, people had not simply sat there in their lairs, paling with terror at every bang of the downstairs door and at every step on the staircase, but had understood they had nothing left to lose and had boldly set up in the downstairs hall an ambush of half a dozen people with axes, hammers, pokers, or whatever else was at hand? … The Organs would very quickly have suffered a shortage of officers and transport and, notwithstanding all of Stalin’s thirst, the cursed machine would have ground to a halt! If … if … We didn’t love freedom enough. And even more – we had no awareness of the real situation … We purely and simply deserved everything that happened afterward.

So what does this mean practically? It means people need to start organising locally with people they trust, building a network in their town or county, coordinating with friendly local power holders. It means stockpiling the necessary tools for the maintenance of their freedoms. It means training to shoot, learning how to use comms, thinking both strategically and tactically — obtaining the knowledge to use with your organising. Most of all, it means being morally and temperamentally prepared to oppose the enemies of our people, both foreign and domestic.

December 7, 2023

QotD: Displacing the “little platoons”

Where government moves in, community retreats, civil society disintegrates and our ability to control our own destiny atrophies. The result is: families under siege; war in the streets; unapologetic expropriation of property; the precipitous decline of the rule of law; the rapid rise of corruption; the loss of civility and the triumph of deceit. The result is a debased, debauched culture which finds moral depravity entertaining and virtue contemptible.

Janice Rogers Brown, “A Whiter Shade of Pale”, a speech to the Federalist Society, 2000-04-11.

November 28, 2023

“This was a document from a parallel universe with familiar-sounding people and places, but a totally bizarre worldview and culture”

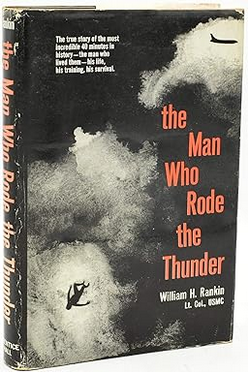

In the latest addition to Mr. and Mrs. Psmith’s Bookshelf, John Psmith reviews The Man Who Rode the Thunder, by William H. Rankin:

Like many little boys, I loved learning lists of things. One day it was clouds. How could I not love them? The names were fluffy and Latinate, delicate little words like “cumulus” and “cirrus” that sounded like they might float away on a puff of wind. But there was also a structure to the words, intimations and hints of taxonomy. Was the relationship of an altocumulus to an altostratus the same as that of a cirrocumulus to a cirrostratus? I wasn’t sure, but it seemed likely! So here I had not just a heap of words, but something more like a map to making sense of a new part of the world.

So I learned the names of all the clouds, but I quickly got bored of most of them. Only one of them held my attention, but it made up for the rest by becoming an obsession. Yes, it was the mighty cumulonimbus, the towering, violent monster that heralds the approach of a thunderstorm. By then I had already met plenty of them — one of my earliest memories is of huddling with my mother in the room of our house that was farthest from any exterior walls, while lightning struck again and again and again, the echoes of the previous thunderclap still reverberating off the landscape when the next one began. What, I wondered, would it be like to be inside one?

There’s one man who knows. His name is Colonel William H. Rankin, and he fell through a thunderstorm and lived to tell the tale. After his ordeal Rankin published a memoir that was a bestseller in the early ’60s, but is out of print today. If you click the Amazon link at the top of this page, you will see that secondhand copies of the paperback edition go for about $150. If that’s too steep for you, I’m told that

Good Samaritanscommunists have uploaded high-quality scans of the book to various nefarious and America-hating websites, but this is a patriotic Substack and we would never condone that sort of behavior. Be warned!I sought out and read Rankin’s memoir for the part where he falls through a cloud, so I was planning on skimming and/or skipping the hundred or so pages where he narrates his life and career up to that point. When I actually cracked open the

They say you should read books to broaden yourself, to learn about foreign peoples and about cultures not your own. I was unprepared for late 1950s America being as foreign as it turned out to be. There’s a whole genre comprised of parodying the supposed mid-century American combo of sunny faith in scientific progress, squeaky-clean public morality, and blithe indifference to the horrors of industrial warfare. In my own reading and watching, I had only ever encountered the parodies, never the genuine article, until I read this book. Rankin’s memoir exudes gee-whiz enthusiasm from every pore. He is patriotic without a trace of irony, giddy as a schoolboy about advances in jet propulsion, and then uses a totally unchanged tone of giddiness and enthusiasm to describe melting hundreds of Korean peasants with napalm.

Reading this stuff fills me with the same feeling of vertigo that I get reading about Bronze Age Greek warriors — here is a human being just like me, but inhabiting a cultural, spiritual, and memetic universe so different from mine. Are we the same species? If we were to meet each other would we even be able to communicate? Or perhaps every age has had people like him and people like me, and all that’s changed is that the dominant mode of social interaction shifted from favoring one of us to the other. After all, I know people today who are incapable of irony or reflection. For instance, TSA agents. Was 1950s America an entire society of TSA agents? And if so, what am I to make of the fact that in so many ways it seems to have been more functional than America today?

November 23, 2023

November 19, 2023

November 15, 2023

November 9, 2023

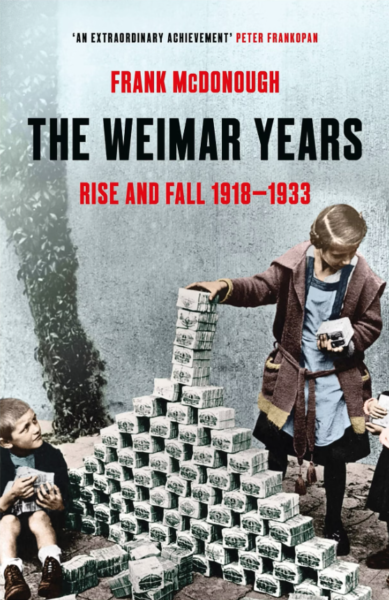

Remembering Weimar

In The Critic, Darren O’Byrne reviews some recent books on German society between the Armistice of 1918 and the rise of Hitler, including Frank McDonough’s The Weimar Years: Rise and Fall 1918–1933.

One of the latest additions to the canon is Frank McDonough’s The Weimar Years (1918–33). A prequel to his two-volume narrative history of the Third Reich, The Hitler Years, it sets out to explain the Nazis’ rise to power by examining the reasons why democracy failed in Germany. Like the earliest histories of the period, the Republic is not examined on its own terms but rather as a kind of backstory to what followed, the numerous crises that befell it being used to explain the ultimate catastrophe.

Structured chronologically, the book provides a devastating, play-by-play account of why, for McDonough, democracy stood little chance in Germany. Defeat in World War I, the Kaiser’s abdication and the humiliating terms of the Versailles treaties challenged the legitimacy of the Republic from the start, as did its failure to contain political violence. Crippling inflation and mounting government debt, exacerbated by the obligation to pay reparations to the Allies, hampered German economic recovery from the start and threatened to wipe out the middle classes.

A degree of economic stability did return in the mid-1920s, but the country experienced its second “once-in-a-lifetime” economic crisis in the early 1930s, causing further instability and ultimately paving the way for Hitler. It’s a well-known story, skilfully retold for a contemporary audience by one of the foremost authorities on modern German history.

Does McDonough tell us anything we didn’t already know? The answer, in short, is no. In comparison to other recent histories of the period, more attention is paid here to high politics than Weimar’s cultural achievements, which are mentioned, but this tends to disrupt the flow of what is otherwise a high-paced, edge-of-the-seat political history of Germany’s first democracy. Despite being nearly 600 pages in length, the book’s focus is quite narrow, with little attention paid to what was happening below the national level in the federal states.

This may seem like an inane criticism. Who, after all, would demand to read more about Buckinghamshire in a political history of interwar Britain? However, the Weimar Republic, like Germany today, was a federation. Understanding what was happening in states like Prussia, which contained three-fifths of Germany’s population, is crucial to understanding the country as a whole.

Indeed, McDonough places some of the blame for Weimar’s collapse on the Social Democrats, who he argues should have participated in more national governments. Prussia was governed by an SPD-led coalition for most of the Weimar years, though, yet the Republic still fell. McDonough sees another reason for this fall in the failure to purge the military and civil service of hostile elements.

Again, Prussia replaced a considerable number of these officials with others loyal to the new democratic order, yet the Republic still fell. The book’s rigid focus on high politics, in short, obscures an understanding of the more structural reasons why democracy failed.

Unlike most history books, however, The Weimar Years is a genuine page-turner, full of lessons for those who want to learn something about the present from the past. It’s also a beautiful book to hold, full of period photos that help bring the story alive. This all makes the book worth reading, even if there’s not much in it that can’t be found in other histories of the period.

November 8, 2023

Mel Blanc on How He Created His Iconic Voices | Carson Tonight Show

Johnny Carson

Published 27 Jun 2023Original Airdate: May 26, 1983

(more…)