Chris Bray puts on the old biohazard suit and goes wading into the political book section, this time looking at two recent tomes by NeverTrumpers Robert Kagan and Tom Nichols:

If you want to know where we are as a country, get your hands on a copy of Robert Kagan’s new book, Rebellion. Don’t worry, you won’t even need to crack the spine and open it. Kagan, who married the Queen of Eternal War Victoria Nuland and helped found the now defunct neoconservative Project for a New American Century, has written a warning about the dangerous renascence of antiliberalism in American political life: intolerance, a rejection of minority rights, hatred of progress. America is in deep trouble, Kagan warns. We’re close to losing our democracy! You can already see the freshness and originality of his thought.

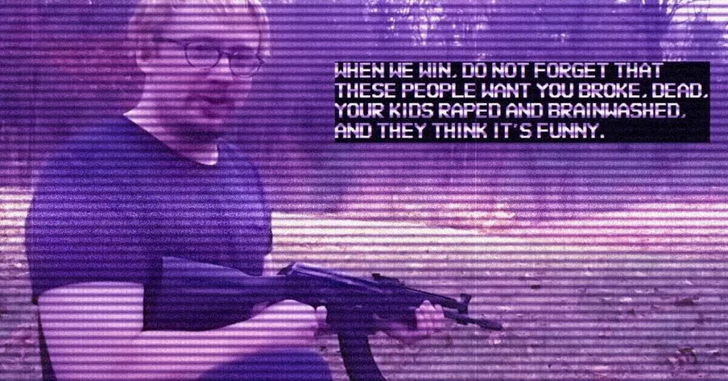

Flip it. Take the book, turn it around, and look at that back cover, which carries an excerpt from inside, getting right to the meat of the thing. The problem isn’t the media, Kagan concludes. And it isn’t government. It isn’t a problem with institutions at all: “The problem is and has always been the people and their beliefs”. The thing that’s wrong with America is Americans, full stop. The country works brilliantly, except for the existence of the population. Imagine how healthy we would become if we could just get rid of them.

Should you make the mistake of opening the book, your experience will get worse in a hurry. The intellectual muddle is fatal. Here’s Kagan’s summary of the one big problem that runs through all of American history: “A straight line runs from the slaveholding South in the early to mid-nineteenth century to the post-Reconstruction South of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, to the second Ku Klux Klan of the 1920s, to the Dixiecrats of the 1940s and 1950s, to Joseph McCarthy and the John Birch Society of the 1950s and 60s, to the burgeoning Christian nationalist movement of recent decades, to the New Right of the Reagan Era, to the Republican Party of today.”

All of those movements are precisely the same, you see. Ronald Reagan was a latter-day Ben Tillman, the Birchers merely a rebrand for the 1940s Southern Democrats, and Barry Goldwater was a fitting heir to Nathan Bedford Forrest. A shrewd mind is at work here. All, Kagan concludes, were figures representing “antiliberal groups”: “All have sought to ‘make America great again,’ by defending and restoring the old hierarchies and traditions that predated the Revolution.” The American Revolution, he means. The Dixiecrats and the Birchers and Reagan and Trump all want to restore Parliamentary supremacy and the landed aristocracy, or … something.

But pretend, for a moment, that Kagan has made some form of coherent statement about American history. He is arguing for the protection of the liberal order, the dignity of the common man and the premise that we’re all created equal. At the same time, he says, the biggest problem with America is … the American people themselves. How do those two claims fit together? What kind of politics can we frame around the dignity and inherent worth of the common man, who is stupid and worthless?

See also, on this theme, anything the former U.S. Naval War College professor Tom Nichols has written in the last decade, such as his warning in Our Own Worst Enemy: The Assault from Within on Modern Democracy that “our fellow citizens are an intolerable threat to our own safety” — a claim that closely mirrors Kagan’s warning about America being plagued by Americans. Consider this framing very carefully: if a threat is intolerable, what do you have to do about it?

Kagan’s base argument sounded better in the original German.