There is no more evanescent quality than modernity, a rather obvious or even banal observation whose import those who take pride in their own modernity nevertheless contrive to ignore. Having reached the pinnacle of human achievement by living in the present rather than in the past, they assume that nothing will change after them; and they also assume that the latest is the best. It is difficult to think of a shallower outlook.

Of course, in certain fields the latest is inclined to be best. For example, no one would wish to be treated surgically using the methods of Sir Astley Cooper: but if we want modern treatment, it is not because it is modern but because it better as gauged by pretty obvious criteria. If it were worse (as very occasionally it is), we should not want it, however modern it were.

Alas, the idea of progress has infected important spheres in which it has no proper application, particularly the arts. It is difficult to overestimate the damage that the gimcrack notion of teleology inhering in artistic endeavour has inflicted on all the arts, exemplified by the use of the term avant-garde: as if artists were, or ought to be, soldiers marching in unison to a predetermined destination. If I had the power to expunge a single expression from the vocabulary art criticism, it would be avant-garde.

Theodore Dalrymple, “Architectural Dystopia: A Book Review”, New English Review, 2018-10-04.

January 16, 2023

QotD: The avant-garde

December 12, 2022

The British Empire(s)

At Spiked, James Heartfield discusses the changing attitudes toward British imperial history:

Renewed interest in the history of the British Empire has generated a great amount of fascinating research and reflection. Over the past decade or more, there have been many books written about the empire – popular, academic, polemical and picaresque. There has been Akala’s Natives, William Dalrymple’s The Anarchy, Shashi Tharoor’s Inglorious Empire and Caroline Elkins’ Legacy of Violence, to name just a few.

Today’s approach to the British Empire is invariably critical – often stridently so. It marks a change to the attitude widely held half a century ago, when books on the empire tended to be elegiac farewells, like Paul Scott’s novel, The Jewel in the Crown, or Jan Morris’s Pax Britannica. Today’s critical approach to the empire is certainly a far cry from that which prevailed for a brief moment around the time that Margaret Thatcher was taking back the Falkland Islands. Back then, there was even an attempt at the moral rehabilitation of the empire.

[…]

But there are downsides to the self-excoriating criticism of Britain’s past. Often this approach to history turns into a debilitating exercise in self-loathing, an act of guilt-mongering. Many others have pointed out the limitations of this kind of morbid raking over the coals. But what is just as worrying is that the more we posture over Britain’s colonial past, the less we seem to understand it.

The moralistic framework in which we teach and discuss colonial history reduces our understanding to a single note of complaint. Hence, many historians today now write as if they have to make a case against the empire. This is just kicking at an open door. The empire has very few champions today. And the great British public is certainly not nostalgic for its return, despite some commentators arguing otherwise. Indeed, an ever growing majority think that the empire was a bad thing.

There is another problem with this approach to Britain’s colonial past. It situates readers outside of history. It encourages them to adopt a moralistic rather than historical approach to colonialism. They can do little more than judge the empire as evil. And in doing so, it flattens out the different periods of the colonial project into one long uniform timeline of subjugation. Collapsing distinct periods and stages together leads to a great confusion. For instance, in many accounts, there appears to be little difference between 18th-century British colonialism, which was dominated by slave trading, and the British colonialism of the late 19th century, which was marked by anti-slavery. It is important not to reduce the long history of the empire to a single motivating cause, be it the “English genius” of earlier celebratory accounts or today’s contention that it was all driven by “white supremacy”.

I seek to address these problems in my new book, Britain’s Empires: A History, 1600-2020. There I draw out the differences between the distinctive stages of Britain’s colonial history.

To do this, it is necessary to step back from moral judgement, which foregrounds our attitudes today, in order to try to understand what motivated people back then. That often means looking at a society’s changing social and economic organisation. Britain’s Empires is a history of the empire that holds on to a sense of historical change, and tries to understand the interrelation of its component parts.

The distinct eras of British colonialism are: the Old Colonialism (1600 to 1776); the Empire of Free Trade (1776-1870); the New Colonialism (1870-1945); and the period of decolonisation during the Cold War era (1946-1989). Britain’s Empires ends with an account of the “humanitarian imperialism” of the 1990s up until the present day. This periodisation aims to reflect the objective moments of transition.

December 8, 2022

November 30, 2022

James Gillray

In The Critic, James Stephens Curl reviews a new biography of the cartoonist and satirist James Gillray (1756-1815), who took great delight in skewering the political leaders of the day and pretty much any other target he fancied from before the French Revolution through the Napoleonic wars:

During the 1780s Gillray emerged as a caricaturist, despite the fact that this was regarded as a dangerous activity, rendering an artist more feared than esteemed, and frequently landing practitioners into trouble with the law. Gillray began to excel in invention, parody, satire, fantasy, burlesque, and even occasional forays into pornography. His targets were the great and good, not excepting royalty. But his vision is often dark, his wit frequently cruel and even shockingly bawdy: some of his own contemporaries found his work repellent. He went for politicians: the Whigs Charles James Fox (1749-1806), Edmund Burke (1729-97), and Richard Brinsley Butler Sheridan (1751-1816) on the one hand, and William Pitt (1759-1806) on the other. Fox was a devious demagogue (“Black Charlie” to Gillray); Burke a bespectacled Jesuit; and Sheridan a red-nosed sot. But Gillray reserved much of his venom for “Pitt the Bottomless”, “an excrescence … a fungus … a toadstool on a dunghill”, and frequently alluded to a lack of masculinity in the statesman, who preferred to company of young men to any intimacies with women, although the caricaturist’s attitude softened to some extent as the wars with the French went on.

As the son of a soldier who had been partly disabled fighting the French, Gillray’s depictions of the excesses of the Revolution were ferocious: one, A Representation of the horrid Barbarities practised upon the Nuns by the Fish-women, on breaking into the Nunneries in France (1792), was intended as a warning to “the FAIR SEX of GREAT BRITAIN” as to what might befall them if the nation succumbed to revolutionary blandishments. The drawing featured many roseate bottoms that had been energetically birched by the fishwives. He also found much to lampoon in his depictions of the Corsican upstart, Napoléon.

[…]

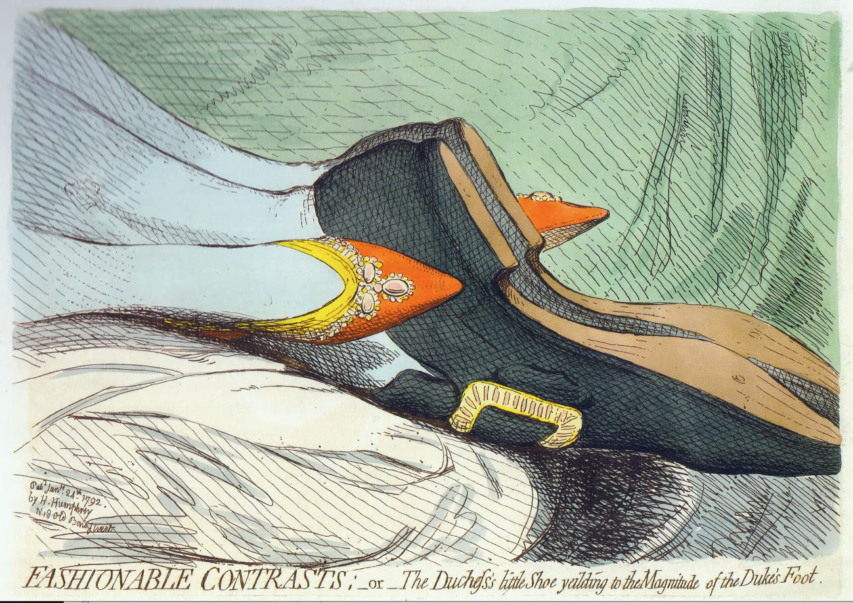

Some of Gillray’s works would pass most people by today, thanks to the much-trumpeted “world-class edication” which is nothing of the sort: one of my own favourites is his FASHIONABLE CONTRASTS;—or—The Duchefs’s little Shoe yeilding to the Magnitude of the Duke’s Foot (1792), which refers to the remarkably small hooves of Princess Frederica Charlotte Ulrica Catherina of Prussia (1767-1820), who married Frederick, Duke of York and Albany (1763-1827) in 1791: their supposed marital consummation is suggested by Gillray’s slightly indelicate rendering, in which the Duke’s very large footwear dwarfs the delicate slippers of the Duchess.

“In 1791 and 1792, there was no one who received more attention in the British press than Frederica Charlotte, the oldest daughter of the King of Prussia, whose marriage to the second (and favorite) son of King George and Queen Charlotte, Prince Frederick, the Duke of York set off a media frenzy that can only be compared to that of Princess Diana in our own day.”

Description from james-gillray.org/fashionable.htmlAll that said, this is a fine book, beautifully and pithily written, scholarly, well-observed, and superbly illustrated, much in colour. However, it is a very large tome (290 x 248 mm), and extremely heavy, so can only be read with comfort on a table or lectern. The captions give the bare minimum of information, and it would have been far better to have had extended descriptive captions under each illustration, rather than having to root about in the text, mellifluous though that undoubtedly is.

What is perhaps the most important aspect of the book is to reveal Gillray’s significance as a propagandist in time of war, for the images he produced concerning the excesses of what had occurred in France helped to stiffen national resolve to resist the revolutionaries and defeat them and their successor, Napoléon, whose own model for a new Europe was in itself profoundly revolutionary. What he would have made of the present gang of British politicians must remain agreeable speculation.

November 22, 2022

November 16, 2022

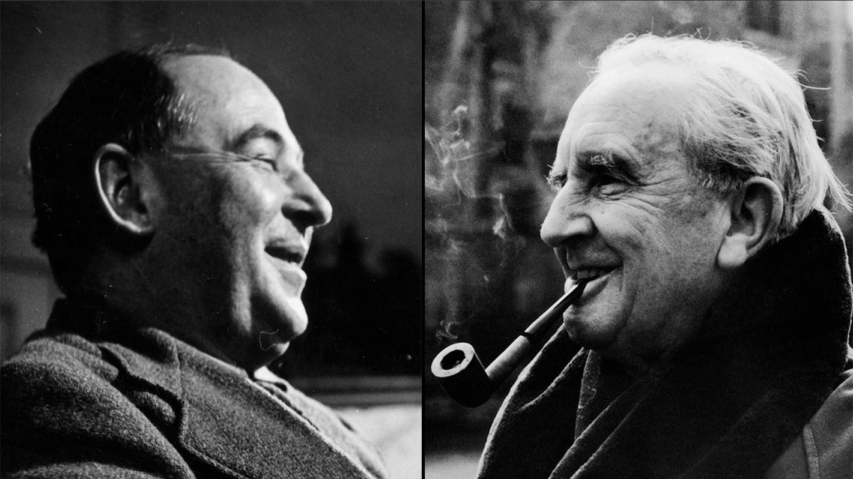

C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien … arch-dystopians?

In The Upheaval, N.S. Lyons considers the literary warnings of well-known dystopian writers like Aldous Huxley and George Orwell, but makes the strong case that C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien were even more prescient in the warnings their works contain:

Which dystopian writer saw it all coming? Of all the famous authors of the 20th century who crafted worlds meant as warnings, who has proved most prophetic about the afflictions of the 21st? George Orwell? Aldous Huxley? Kurt Vonnegut? Ray Bradbury? Each of these, among others, have proved far too disturbingly prescient about many aspects of our present, as far as I’m concerned. But it could be that none of them were quite as far-sighted as the fairytale spinners.

C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien, fast friends and fellow members of the Inklings – the famous club of pioneering fantasy writers at Oxford in the 1930s and 40s – are not typically thought of as “dystopian” authors. They certainly never claimed the title. After all, they wrote tales of fantastical adventure, heroism, and mythology that have delighted children and adults ever since, not prophecies of boots stamping on human faces forever. And yet, their stories and non-fiction essays contain warnings that might have struck more surely to the heart of our emerging 21st century dystopia than any other.

The disenchantment and demoralization of a world produced by the foolishly blinkered “debunkers” of the intelligentsia; the catastrophic corruption of genuine education; the inevitable collapse of dominating ideologies of pure materialist rationalism and progress into pure subjectivity and nihilism; the inherent connection between the loss of any objective value and the emergence of a perverse techno-state obsessively seeking first total control over humanity and then in the end the final abolition of humanity itself … Tolkien and Lewis foresaw all of the darkest winds that now gather in growing intensity today.

But ultimately the shared strength of both authors may have also been something even more straightforward: a willingness to speak plainly and openly about the existence and nature of evil. Mankind, they saw, could not resist opening the door to the dark, even with the best of intentions. And so they offered up a way to resist it.

Subjectivism’s Insidious Seeds

The practical result of education in the spirit of The Green Book must be the destruction of the society which accepts it.

When Lewis delivered this line in a series of February 1943 lectures that would later be published as his short book The Abolition of Man, it must have sounded rather ridiculous. Britain was literally in a war for its survival, its cities being bombed and its soldiers killed in a great struggle with Hitler’s Germany, and Lewis was trying to sound the air-raid siren over an education textbook.

But Lewis was urgent about the danger coming down the road, a menace he saw as just as threatening as Nazism, and in fact deeply intertwined with it, give that:

The process which, if not checked, will abolish Man goes on apace among Communists and Democrats no less than among Fascists. The methods may (at first) differ in brutality. But many a mild-eyed scientists in pince-nez, many a popular dramatist, many an amateur philosopher in our midst, means in the long run just the same as the Nazi rulers of Germany. Traditional values are to be “debunked” and mankind to be cut into some fresh shape at will (which must, by hypothesis, be an arbitrary will) of some few lucky people …

Unfortunately, as Lewis would later lament, Abolition was “almost totally ignored by the public” at the time. But now that our society seems to be truly well along in the process of self-destruction kicked off by “education in the spirit of The Green Book“, it might be about time we all grasped what he was trying to warn us about.

This “Green Book” that Lewis viewed as such a symbol of menace was his polite pseudonym for a fashionable contemporary English textbook actually titled The Control of Language. This textbook was itself a popularization for children of the trendy new post-modern philosophy of Logical Positivism, as advanced in another book, I.A. Richards’ Principles of Literary Criticism. Logical Positivism saw itself as championing purely objective scientific knowledge, and was determined to prove that all metaphysical priors were not only false but wholly meaningless. In truth, however, it was as Lewis quickly realized actually a philosophy of pure subjectivism – and thus, as we shall see, a sure path straight out into “the complete void”.

In Abolition, Lewis zeros in on one seemingly innocuous passage in The Control of Language to begin illustrating this point. It relates a story told by the English poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge, in which two tourists visit a majestic waterfall. Gazing upon it, one calls it “sublime”. The other says, “Yes, it is pretty.” Coleridge is disgusted by the latter. But, as Lewis recounts, of this story the authors of the textbook merely conclude:

When the man said This is sublime, he appeared to be making a remark about the waterfall … Actually … he was not making a remark about the waterfall, but a remark about his own feelings. What he was saying was really I have feelings associated in my mind with the word “sublime”, or shortly, I have sublime feelings … This confusion is continually present in language as we use it. We appear to be saying something very important about something: and actually we are only saying something about our own feelings.

For Lewis, this “momentous little paragraph” contains all the seeds necessary for the destruction of humanity.

November 10, 2022

QotD: Sarah’s rules of art

… the botanic gardens were holding a sculpture exhibit, called “human nature” with statues from various times and places.

And why was this a bad idea, Sarah?

Mostly because I’m married to a mathematician. There is a certain … ah … compulsiveness that comes with it. If there’s something that’s numbered and has a route, we OF COURSE have to follow the route and see every single statue, even if that’s not what we set out to do.

This made things very interesting, since the wedding parties were blocking some of the statues, and others we could see from a distance were the sort of modern art that your kids could do with a backyard forge, meaning the actual level of artistry was about the level of a kindergartner, only they used metal instead of playdough.

This leads us to Sarah’s first rule of art: if people viewing it have trouble telling it from accidental formations, it’s probably not art.

The second corollary of this is: if you need an elaborate card pointing out to you that it’s art, it’s probably not art.

The third would be that if you need a placard explaining to you how daring and courageous this art is, and how it defied some tyrannical regime at great peril to the artist’s life, it’s not only not art, you’re in the presence of a self-aggrandizing conman.

Sarah Hoyt, “Art and Revolution”, According to Hoyt, 2019-05-31.

November 7, 2022

QotD: The rise of architectural modernism

Making Dystopia is not just a cri de coeur, however. It is a detailed account of the origins, rise, effect, and hegemony of architectural modernism and its successors, and of how architecture became (to a large extent) a hermetic cult that seals itself off from the criticism of hoi polloi — among whom is included Prince Charles — and established its dominance by a mixture of bureaucratic intrigue, intellectual terrorism, and appeal to raw political and financial interest. If success is measured by power and hold over a profession rather than by intrinsic worth, then the modernist movement in architecture has been an almost unparalleled success. Only relatively recently has resistance begun to form, and often all too late:

Many ingenious lovely things are gone

That seemed sheer miracle to the multitude.Professor Curl’s book is particularly strong on the historiographical lies peddled by the apologists for modernism, and on the intellectual weakness of the arguments for the necessity of modernism. For example, architectural historians and theoreticians such as Sigfried Giedion, Arthur Korn, and Nikolaus Pevsner claimed to see in modernism the logical continuation of the European architectural tradition, and Pevsner even recruited such figures as William Morris and C.F.A. Voysey as progenitors of the movement. Pevsner was so enamored of Gropius and the Modernists that he wanted to claim a noble descent for them, as humble but ambitious people were once inclined to find a distant aristocratic forebear. Yet Voysey could hardly have been more hostile to the movement that co-opted him. The Modern Movement, he said,

was pitifully full of such faults as proportions that were vulgarly aggressive, mountebank eccentricities in detail, and windows built lying down on their sides. … This was false originality, the true originality having been for all time the spiritual something given to the development of traditional forms by the individual artist.

Pevsner (to whom, incidentally, Curl pays tribute for his past generosity to young scholars, including himself), with all the academic and moral prestige and authority that attached to his name, was able to incorporate Voysey — unable to speak for himself or protest after his death — into the direct ancestry of modernism, even though the merest glance at his work, or at that of William Morris, should have been sufficient to warn anyone that Pevsner’s historiography made a bed of Procrustes seem positively made to measure.

Theodore Dalrymple, “Crimes in Concrete”, First Things, 2019-06.

October 28, 2022

QotD: “Cliodynamics”, aka “megahistory”

For this week’s musing, I want to discuss in a fairly brief way, my views of “megahistory” or “cliodynamics” – questions about which tend to come up a fair bit in the comments – and also Isaac Asimov, after a fashion. Fundamentally, the promise of these sorts of approaches is to apply the same kind of mathematical modeling in use in many of the STEM fields to history with the promise of uncovering clear rules or “laws” in the noise of history. It is no accident that the fellow who coined the term “cliodynamics”, Peter Turchin, has his training not in history or political science but in zoology; he is trying to apply the sort of population modeling methods he pioneered on Mexican Bean Beetles to human populations. One could also put Steven Pinker, trained as a psychologist, and his Better Angels in this category as well and long time readers will know how frequently I recommend that folks read Azar Gat, War in Human Civilization instead of The Better Angels of our Nature.1

Attentive readers will have already sensed that I have issues with these kinds of arguments; indeed, for all of my occasional frustrations with political science literature (much of which is perfectly fine, but it seems a frequent and honestly overall positive dynamic that historians tend to be highly critical of political scientists) I consider “cliodynamics” to generally take the worst parts of data-driven political science methodologies to apotheosis while discarding most of the virtues of data-driven poli-sci work.

As would any good historian, I have a host of nitpicks, but my objection to the idea of “cliodynamics” has to do with the way that it proposes to tear away the context of the historical data. I think it is worth noting at the outset the claim actually being made here because there is often a bit of motte-and-bailey that goes on, where these sorts of megahistories make extremely confident and very expansive claims and then when challenged is to retreat back to much more restricted claims but Turchin in particular is explicit in Secular Cycles (2009) that “a basic premise of our study is that historical societies can be studied with the same methods physicists and biologists used to study natural systems” in the pursuit of discovering “general laws” of history.

Fundamentally, the approach is set on the premise that the solution to the fact that the details of society are both so complex (imagine charting out the daily schedules of every person one earth for even a single day) and typically so poorly attested is to aggregate all of that data to generate general rules which could cover any population over a long enough period. To my mind, there are two major problems here: predictability and evidence. Let’s start with predictability.

And that’s where we get to Isaac Asimov, because this is essentially also how the “psychohistory” of the Foundation series functions (or, for the Star Trek fans, how the predictions in the DS9 episode “Statistical Probabilities“, itself an homage to the Foundation series, function). The explicit analogy offered is that of the laws that govern gasses: while no particular molecule of a gas can modeled with precision, the entire body of gas can be modeled accurately. Statistical probability over a sufficiently large sample means that the individual behaviors of the individual gas molecules combine in the aggregate to form a predictable whole; the randomness of each molecule “comes out in the wash” when combined with the randomness of the rest.2

I should note that Turchin rejects comparisons to Asimov’s psychohistory (but also embraced the comparison back in 2013), but they are broadly embraced by his boosters. Moreover, Turchin’s claim at the end of that blog post that “prediction is overrated” is honestly a bit bizarre given how quick he is when talking with journalists to use his models to make predictions; Turchin has expressed some frustration with the tone of Graeme Wood’s piece on him, but “We are almost guaranteed” is a direct quote that hasn’t yet been removed and I can speak from experience: The Atlantic‘s fact-checking on such things is very vigorous. So I am going to assume those words escaped the barrier of his teeth and also I am going to suggest here that “We are almost guaranteed” is, in fact, a prediction and a fairly confident one at that.

The problem with applying something like the ideal gas law – or something like the population dynamics of beetles – to human societies is fundamentally interchangeability. Statistical models like these have to treat individual components (beetles, molecules) the way economists treat commodities: part of a larger group where the group has qualities, but the individuals merely function to increase the group size by 1. Raw metals are a classic example of a commodity used this way: add one ton of copper to five hundred tons of copper and you have 501 tons of copper; all of the copper is functionally interchangeable. But of course any economist worth their pencil-lead will be quick to remind you that not all goods are commodities. One unit of “car” is not the same as the next. We can go further, one unit of “Honda Civic” is not the same as the next. Heck, one unit of 2012 Silver Honda Civic LX with 83,513 miles driven on it is not the same as the next even if they are located in the same town and owned by the same person; they may well have wildly different maintenance and accident histories, for instance, which will impact performance and reliability.

Humans have this Honda Civic problem (that is, they are not commodities) but massively more so. Now of course these theories do not formally posit that all, say, human elites are the same, merely that the differences between humans of a given grouping (social status, ethnic group, what have you) “come out in the wash” at large scales with long time horizons. Except of course they don’t and it isn’t even terribly hard to think of good examples.

1 Yes, I am aware that Gat was consulted for Better Angels and blurbed the book. This doesn’t change my opinion of the two books. my issue is fundamentally evidentiary: War is built on concrete, while Better Angels is built on sand when it comes to the data they propose to use. As we’ll see, that’s a frequent issue.

2 Of course the predictions in the Foundation series are not quite flawlessly perfect. They fail in two cases I can think of: the emergence of a singular exceptional individual with psychic powers (the Mule) and situations in which the subjects of the predictions become aware of them. That said Seldon is able to predict things with preposterous accuracy, such that he is able to set up a series of obstacles for a society he knows they will overcome. The main problem is that these challenges frequently involve conflict or competition with other humans; Seldon is at leisure to assume such conflicts are predictable, which is to say they lack Clausewitzian (drink!) friction. But all conflicts have friction; competition between peers is always unpredictable.

Bret Devereaux, “Fireside Friday: October 15, 2021”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2021-10-15.

October 22, 2022

Two new works on British architecture through the years

In The Critic, James Stevens Curl discusses two recent books on the “monuments and monstrosities” of British architecture:

The most startling achievement of the Victorian period was Britain’s urbanisation. By the 1850s the numbers living in rural parts were fractionally down on those in urban areas. By the end of Victoria’s reign more than 75 per cent of the population were town-dwellers, and a romantic nostalgic longing for a lost rural paradise was fostered by those who denigrated urbanisation. This myth of a lost rural ideal led to phenomena such as garden cities and suburbia. Anti-urbanists and critics of the era detested the one thing that gave the Victorian city its great qualities: they were frightened of and hated the Sublime.

These two books deal with the urban landscape in different ways. Tyack provides a chronological narrative of the history of some British towns and cities spread over two millennia from Roman times to the present day, so his is a very ambitious work. Most towns of modern Britain already existed in some form by 1300, he rightly states, though a few were abandoned, such as Calleva Atrebatum (Silchester) in Hampshire, a haunted place of great and poignant beauty with impressive remains still visible. Most Roman towns were more successful, surviving and developing through the centuries, none more so than London. Tyack describes several in broad, perhaps too broad, terms.

He outlines the creation of dignified civic buildings from the 1830s onwards, reflecting the evolution of local government as power shifted to the growing professional, manufacturing and middle classes: fine town halls, art galleries, museums, libraries, concert halls, educational buildings and the like proliferated, many of supreme architectural importance. Yet the civic public realm has been under almost continuous attack from central government and the often corrupt forces of privatisation for the last half century.

Tyack is far too lenient when considering the unholy alliances between legalised theft masquerading as “comprehensive redevelopment”, local and national government, architects, planners and large construction firms with plentiful supplies of bulging brown envelopes. Perfectly decent buildings, which could have been rehabilitated and updated, were torn down, and whole communities were forcibly uprooted in what was the greatest assault in history on the urban fabric of Britain and the obliteration of the nation’s history and culture.

One of the worst professional crimes ever inflicted on humanity was the application of utopian modernism to the public housing-stock of Britain from the 1950s onwards: this dehumanised communities, spoiled landscapes and ruined lives, yet the architectural establishment remained in total denial. In 1968–72 the Hulme district of Manchester was flattened to make way for a modernist dystopia created by a team of devotees of Corbusianity.

The huge quarter-mile long six-storey deck-access “Crescents” were shabbily named after architects of the Georgian, Regency and early-Victorian periods (Adam, Barry, Kent and Nash). This monstrous, hubristic imposition rapidly became one of the most notoriously dysfunctional housing estates in Europe, a spectacular failure whose problems were all-too-apparent from the very beginning. Yet in The Buildings of England 1969, Manchester was praised for “doing more perhaps than any other city in England … in the field of council housing”. The “Crescents” were recognised quickly as unparalleled disasters and hated by the unfortunates forced to live there. They were demolished in the 1990s, but the creators of that hell were never punished.

October 14, 2022

The commercial failure of Bros

With the movie failing to find much of an audience, the director and lead actor blame homophobia, because that’s far easier than accepting that rom-com movies are quaint, out-of-date, and stale in the modern hookup culture:

In the case of movies, one might respond to Stoller and Eichner by saying that entertainers are supposed to provide products that the viewing public wishes to see. It might surprise the team behind the didactic Bros that many of us watch movies to be entertained, not to be preached at, seeing them as brief, trivial moments of escape from the drudge of daily life, not an opportunity to (as the Victorians would have said) “improve” ourselves. But even though it has proved an abject commercial failure, the movie is nonetheless instructive in how our culture is changing. And both its production values and its failure are likely signs not of the LGBTQ movement’s influence stalling, but of its remarkable success.

[…]

Romance depends upon sex being costly. It was the difficulty of obtaining sex, the need for that delicate, complicated, and unpredictable interpersonal dance between two people, that was the very essence of what it was to be romantic. In a world where sex is not simply casual but remarkably cheap, the notion of romance is dead. Romance requires a particular kind of culture in order to make sense. A world of hookups, one-night stands, and all-pervasive pornography is not one that gives people the cultural grammar and syntax to understand it. That the movie apparently contains scenes of sex and nudity is hardly exceptional today. But that’s the point: A world where sex and nudity are displayed on the screen is not a world where romance has any place. Just as explicit rap lyrics reflect a world antithetical to that in which Frank Sinatra sang “Fly me to the moon”, so the endless tedium of explicit sex on celluloid is not that of Audrey Hepburn and Fred Astaire in Funny Face. Romance depends upon social codes of restraint and modesty, and upon the idea that sex is not something casual but something special, even sacred.

The same point can be made with reference to what we might call romantic tragedy. Take Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina. The story simply could not be set in modern America because Anna, married to the tedious Karenin but falling in love with the dashing Vronsky, would simply file for divorce and move out of Karenin’s house and into that of her lover. The tragic romance is rooted in the impossibility of Anna’s situation, given the way sex is seen through the powerful moral lens of nineteenth-century Russian society. The genre of romantic tragedy depends upon a specific moral framework. So does the genre of romantic comedy. But the sexual revolution has obliterated that moral framework.

To return to Bros, it is frankly as ridiculous to make a rom-com in the twenty-first century as it is to hire a cast and crew on the basis of modern categories of identity rather than professional competence. And, while the Bros team might regard its box office failure as discouraging, it might just as easily be evidence of the triumph of the LGBTQ movement in wider society as it is of a residual resistance to the same. Please don’t blame homophobia for your commercial failure. Romance is dead. And you helped to kill it.

October 9, 2022

October 1, 2022

Johann Hari’s unlikely career resurrection

I have to admit that Johann Hari was pretty much just a British media personality I had a vague awareness of, but I hadn’t paid much attention to him (his Wikipedia sockpuppeting came to my attention in 2011, and I quoted from an article he wrote for the Los Angeles Times in 2019). As this post by Ben at Ben’s Comedy News outlines, I’d largely missed the rest of his fall and rise:

Nowadays, Johann Hari is known as a pop psychology expert. He does TED talks and writes books with simplistic messages like:

- your smartphone is ruining your attention span! (Stolen Focus)

- you should cure your depression by throwing away your medication and joining a book club! (Lost Connections)

- the war on drugs is bad! (Chasing the Scream)

His books get positive blurbs from distinguished thinkers, such as the comedian and twink admirer Stephen Fry, the listicle entrepreneur Arianna Huffington, the feminist and sex offender’s wife Hillary Clinton, the comedian and fake revolutionary Russell Brand, and the TV doctor Doctor Rangan Chatterjee.

But when you look at how actual experts assess his work, it’s not so positive. The neuroscientist Dean Burnett responded to an extract of Lost Connections in his Guardian column, under the title Is everything Johann Hari knows about depression wrong? Burnett points out that:

despite Hari’s prose suggesting he’s uncovered numerous revelations, pretty much everything he “reveals” is well known already

Hari, in pursuit of an anti-anti-depressant narrative, makes the claim that you can be diagnosed with depression and put on medication immediately after a traumatic event like losing a child, which Burnett (who teaches psychiatry) describes as:

at best a staggering exaggeration, at worst an active fabrication to support a narrative.

But this article isn’t about what Johann Hari has been doing recently. It’s about what Hari was up to before he reinvented himself as some kind of expert, back when he was a journalist who ended up being disgraced.

It’s about how Hari has somehow rounded allegations of serious fabrication down to a record of minor plagiarism. It’s about how in trying to attack his critics, he seems to have inadvertently revealed his penchant for little brother incest fantasies with a troubling racial dimension. It’s about how I tried to fix the record on Wikipedia, and ran into trouble as Wikipedia’s policies collided with the sorry state of British journalism.

Back in 2010, Johann Hari was a star newspaper columnist (if you’re a millennial that means he wrote hot takes that got lots of clicks; if you’re Gen Z, think of him as a viral TikTok star but with words on paper).

In 2011 he was disgraced and kicked out of the profession.

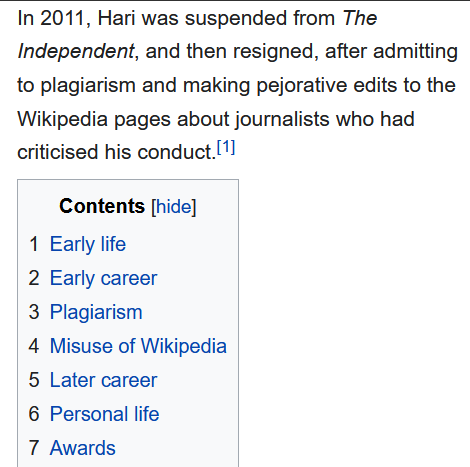

Now if you look at the articles that were written about his comeback, like this New Statesman piece or this Guardian piece you’d conclude that he was disgraced for two things:

plagiarism – specifically, taking quotes from text someone had written in a book or article, and pretending that the person had said it directly to him

abuse of Wikipedia – in particular, using a fake identity to edit the pages of professional rivals with false allegations

I followed the whole Hari affair pretty closely at the time (I didn’t like him because he had been a cheerleader for the Iraq War, so I enjoyed watching his career go down in flames).

When his latest book came out a month ago, I looked at his Wikipedia entry. Wikipedia saves the history of all the different versions of each page, so here is a link to what I saw when I did that.

And here’s part of the summary and the table of contents:

The whole article struck me as weird because it didn’t mention two things I clearly remembered:

- Hari got in trouble, not just for minor plagiarism, but for allegedly making things up completely.

- Even more memorably, the fake identity he used to edit Wikipedia, “David Rose”, was also used to author an incest kink porn story with a hilarious title.

You can see why Hari (and whatever reputation management consultants he has working for him) would want to focus on the “plagiarism” angle. It’s not good to pass off a quote you got from someone’s book as something they told you directly, but it’s not as serious as completely inventing something. I suppose technically it’s plagiarism because you’re pretending you elicited the quote in an interview and you’re not citing the original book; but it’s a lot better than the typical case of plagiarism that involves passing off someone else’s work as your own. Hari’s defence is that he was “cutting corners” because he was under so much pressure due to his meteoric success at young age, etc. etc.

September 18, 2022

QotD: Late night TV’s negative impact on US national culture (aka “Clown nose on, clown nose off”)

I truly believe that Tim Pool is absolutely right about where the political poisoning of our National culture comes from.

Shows like Saturday Night Live, the Daily Show, late night television …

They take the news, spin it through a comedy filter, and present it to the masses. This presents an easily digestible, and thus easily believable, simplified and polarized view of events, that their viewers are then encouraged to apply to the news that is coming from real news sources. Anyone who objects to this is “overreacting, or doesn’t have a sense of humor” and thus is dismissed as irrelevant.

And thus the culture of lies continues, and gets ramped up as it spreads.

It’s sickening.

James Resoldier, posting to MeWe‘s “Hoyt’s Huns” group, 2022-06-16. (private group, so no public URL available)

September 6, 2022

Fixing the American education system (other than burning it to the ground and starting over)

At First Things, M.D. Aeschliman reviews The Knowledge Gap: The Hidden Cause of America’s Broken Education System — and How to Fix It by Natalie Wexler:

E.D. Hirsch Jr., distinguished scholar of comparative literature, is the most important advocate for K–12 education reform of the past seventy-five years. Natalie Wexler’s recent book The Knowledge Gap is a helpful examination of Hirsch’s critical analyses and intellectual framework, as well as the elementary school curriculum that he designed — Core Knowledge.

One of Hirsch’s key focal points is the vapid, supposedly “developmentally appropriate” fictions that dominate language arts curricula in elementary schools — mind-numbingly banal stories with single-syllable vocabularies and large pictures. These silly literary fictions and fantasies have helped “dumb down” a hundred years of American students by eliminating or forbidding any substantial reading of expository prose about history and science in the first eight grades. A poignant narrative well worth reading is Harold Henderson’s Let’s Kill Dick and Jane, which details a noble but ultimately losing fight waged by a family firm from 1962 to 1996 against the big textbook publishers.

After a teaching career of fifty years, I agree with Hirsch that the primary problem in American public education is not the high schools, but the poorly organized, ineffective elementary school curricula, including the idiotic books of childish fiction. As Wexler writes, the governing “approach to reading instruction … leaves … many students unprepared to tackle high-school-level work”. Pity the poor high school teachers.

A hundred years ago John Dewey and his lieutenants from Columbia Teachers College, especially William H. Kilpatrick, started dismantling academic “subjects” in favor of “the project method”. They also worked to redefine history as “social studies”, a degenerative development that has continued without cease in our K–12 schools, leading to ludicrous presentism. Dewey and the progressives also attacked traditional language classes — especially phonics but also Latin — opening the way for “naturalistic” literacy instruction that has proved to be ineffective. Yet it should be obvious that students must “learn to read” well early on so as to “read to learn” for high school and college and the rest of their lives. And what they read early on is important.

The “progressive” educational assault on traditional American education had another source, which might be called “soft utopianism”. Twenty-five years ago Hirsch was already writing powerfully — in The Schools We Need and Why We Don’t Have Them — about this romantic-progressive “soft utopianism” and how it conflicted with what is wisest and best in the thinking, writings, and achievements of the founding fathers and their early republic. Yet he also knew — as himself a repentant progressive “mugged by reality” — that in the nineteenth century the republican educational legacy was already under intellectual assault by Rousseau’s American disciples Emerson, Thoreau, and Walt Whitman. Whitman’s egalitarian naturalism was one of Dewey’s greatest inspirations by the early twentieth century.

The progressives particularly dislike history, and our current “Great Awakening” indicates this. A few years ago, the former superintendent of the school system of one of our most “liberal” states said to me in private conversation that “the progressives hate history and won’t tolerate it in the curriculum”. They hate it because any thinking about history requires ethical assumptions and qualitative judgments: What in the past is worth studying? How do we structure our narratives? How do we fairly evaluate historical personalities and events? Which ones were virtuous and beneficial? These and related questions require some standard of justice and the idea that most individuals — in the past and present — have some degree of free will and some disposition to ethics: the “self-evident truths” of our founding document, and of civilization itself.