Atun-Shei Films

Published 24 Dec 2020Checkmate, Lincolnites! Debunking the Lost Cause myth that tens of thousands of black men served as soldiers in the Confederate army during the American Civil War.

Support Atun-Shei Films on Patreon ► https://www.patreon.com/atunsheifilms

Leave a Tip via Paypal ► https://www.paypal.me/atunsheifilms

Buy Merch ► teespring.com/stores/atun-shei-films

#CheckmateLincolnites #CivilWar #AmericanHistory

Original Music by Dillon DeRosa ► http://dillonderosa.com/

Reddit ► https://www.reddit.com/r/atunsheifilms

Twitter ► https://twitter.com/atun_shei~REFERENCES~

[1] “Black Confederate Movement ‘Demented'” (2014). AmericanForum https://youtu.be/fYFIWlGJhjM

[2] Sam Smith. “Black Confederates: Myth and Legend.” American Battlefield Trust https://www.battlefields.org/learn/ar…

[3] “25th USCT: The Sable Sons of Uncle Abe.” National Park Service https://www.nps.gov/articles/25-usct.htm

[4] Justin A. Nystrom. New Orleans After the Civil War (2010). Johns Hopkins Press, Page 20-27

[5] Kevin M. Levin. Searching for Black Confederates (2019). University of North Carolina Press, Page 45

[6] James Parton. General Butler in New Orleans (1864). Mason & Hamlin, Page 516-517

[7] Levin, Page 12-15

[8] Levin, Page 34-35

[9] Myra Chandler Sampson & Kevin M. Levin. “The Loyalty of ‘Heroic Black Confederate’ Silas Chandler” (2012). HistoryNet https://www.historynet.com/loyalty-si…

[10] Levin, Page 82-83

[11] James G. Hollandsworth, Jr. “Looking for Bob: Black Confederate Pensioners After the Civil War” (2007). The Journal of Mississippi History, Vol. LXVIX, Page 304-306

[12] Lewis H. Steiner. An Account of the Operations of the U.S. Sanitary Commission During the Campaign in Maryland, September 1862 (1862). Anson D. F. Randolph, Page 19-20

[13] Levin, Page 32-33

[14] Charles Augustus Stevens. Berdan’s United States Sharpshooters in the Army of the Potomac (1892). Price-McGill Company, Page 54-55

[15] Levin, Page 44

[16] Andy Hall. “Frederick Douglass and the ‘N*gro Regiment’ at First Manassas” (2011). Dead Confederates Blog https://deadconfederates.com/2011/07/…

[17] Jaime Amanda Martinez. “Black Confederates” (2018). Encyclopedia Virginia https://www.encyclopediavirginia.org/…

[18] Levin, Page 58-61

[19] Levin, Page 39

[20] Levin, Page 46

May 13, 2021

Were There Really BLACK CONFEDERATES???!!!

April 26, 2021

Was GENERAL SHERMAN a WAR CRIMINAL?!?!?!?!

Atun-Shei Films

Published 11 Aug 2020Checkmate, Lincolnites! Debunking the Lost Cause myths surrounding William Tecumseh Sherman during the American Civil War, including the Atlanta Campaign, the March to the Sea, and the burning of Columbia — and tackling the “slavery would have gone away on its own” thing while we’re at it. Surprisingly, Johnny Reb gets in one or two really solid points.

[Updated 8 Feb 2023: Vlogging Through History’s reaction video to Atun-Shei’s interpretation is here – https://youtu.be/CTVr4YgB5VI]

(more…)

April 13, 2021

Was it REALLY the WAR of NORTHERN AGGRESSION?!?!?!

Atun-Shei Films

Published 28 Apr 2020Checkmate, Lincolnites! Debunking the Lost Cause myths that Abraham Lincoln was a tyrant, that nobody in the North cared about slavery or abolitionism, and that the warmongering Union invaded the South without provocation or just cause during the Civil War. Featuring some special guest appearances from your favorite kooky historical characters!

[Update, 8 Feb, 2023: Here’s a Vlogging Through History reaction video that amplifies several of the points Atun-Shei makes – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rTQzXG15QsU]

(more…)

April 12, 2021

“War Communism” in the Soviet Union, 1917-1921

J.W. Rich outlines the economic and humanitarian disaster of Soviet “War Communism” that eventually forced Lenin to bring back some limited elements of capitalism to save the country:

In 1917, the Bolsheviks seized power in Moscow after the deposition of the democratic provisional government which had replaced the Tsar. However, the Bolsheviks’ hold on power was far from secure. There was little affection anywhere for the Tsar, but there was no agreement on what form of government should replace the monarchy. Bolshevism had been on the rise for years, but ideas of democracy and liberalism were gaining popularity as well. Shortly after the 1917 revolution, the Russian Civil War broke out between the Reds, the Bolsheviks, and the Whites, a coalition of anti-Bolsheviks that were generally democratic.

Through the course of the civil war, the Bolsheviks gained more power and control over increasingly large amounts of Russia. With this control, they began to implement their Marxist economic ideas into reality. On January 28, 1918, it was decreed that all factories should be directed by state-appointed managers. In effect, this amounted to a near-complete nationalization of industry. In one fell swoop, the vast majority of the production of Russia’s consumer goods was now under the purview and direction of the state.

On May 9, 1918, a grain monopoly was announced over grain production in the country. All grain harvested across the country was now the property of the state. This was extended even further when a general food levy was announced in January 1919. Any and all food was now the property of the state. In addition, local farm authorities were no longer allowed to set the levy based on harvest estimates. In essence, the state would take however much it wanted from the peasants without any concern if they had enough food to feed themselves and their families.

It was at this point that large-scale forced rationing was introduced. Money was made worthless overnight as ration cards were mandated to the entire population. No longer could you buy whatever you wished with the money you had. The goods allocated for you were predetermined on your ration card.

By late 1920, going into 1921, the Russian Civil War was all but over. The Whites had been soundly defeated by the Reds, giving the Bolsheviks control of nearly the entirety of the country. However, despite the victory in the Civil War, the economy at home was beginning to fall apart. Industrial production was at 20% of pre-war levels by 1920. As a result of this lagging production, there were few goods in the cities available. This resulted in a flight from the cities to the countryside. From 1918 to 1920, eight million people emigrated from the cities to the villages, where there was better hope of finding food or some goods. In Moscow and Petrograd, the population declined by 58.2%

The agricultural situation was not much better. Sheldon Richman records that from 1909-1913, gross agricultural output averaged 69 million tons. By 1921, it was just 31 million. From 1909-1913, sown area was over 224 million acres. In 1921, only 158 million acres were sown. This lack of food resulted in a mass loss of population. From 1917 to 1922, the entire population declined by 16 million, not counting immigration and deaths from the civil war.

War Communism was now fully implemented and the Marxist aspirations of Lenin and the Bolsheviks were now fulfilled. For the people that had to live under War Communism, however, the conditions had become intolerable. In February 1921, labor strikes began to emerge all over Russia. With the end of the civil war and living standards continuing to fall, resistance to the Bolsheviks began to spread throughout the country. Moscow was the first city to strike, with other large cities, such as Petrograd, following. The protestors demanded an end to War Communism and a restoration of private enterprise and civil liberties, such as the freedom of speech and assembly.

The protests escalated when the Kronstadt Naval Base mutinied against the government. Once a bastion of Bolshevik support and fervor, the sailors joined with the laborers in demanding reform and change. A force led by Trotsky was dispatched to deal with the mutiny, but Lenin knew that change was needed. The writing was on the wall for War Communism.

April 4, 2021

QotD: Revolution and civil war

I was a crew chief on Blackhawks, in an air assault company. Our job was to fly the infantry troops around and put them where they needed to be. A lot of the time, we would fly through the hills north of [Camp] Bondsteel. When we went that way, we usually flew over a mass grave. One morning, Serb gunmen showed up in a little Albanian village in the hills. They drove everyone out of their homes, forced them to dig their own graves, and then murdered them. Men, women and children. Fathers, mothers, sons, daughters, grandparents.

There was a little memorial with flowers.

Whenever someone starts talking about maybe voting is useless and perhaps other means are necessary to take back our country, I think of Kosovo. That EXACT rhetoric was part and parcel with the disintegration of the Balkans. The rhetoric I see people casually bandying about, we need to confront them everywhere and they deserve no peace, this is the rhetoric and the justification the Serbs used on their way to killing a quarter of a million people in the Balkans. Their former neighbors; often literally.

It’s worth considering whether all those who killed people in Kosovo started with killing in mind, or were they merely trying to right the wrongs that the other side had perpetrated against them? Civilization is a millimeters thin veneer on top an ocean of violence a billion years of evolution deep. If you think it’s acceptable to use violence for political gain, or if you fantasize for revolution, you’re a monster.

Revolution is not what you think it is. Revolution is civil war. Civil war is driving your neighbors from their homes and forcing them to dig their own graves. It is leaving your grandmother behind because she cannot move fast enough to escape the gunmen; and they won’t stop. Yes, there are monsters in places of power, but you are not absolved of your obligations to humanity because of it. That others have foresworn theirs is no excuse. You fetishize misery you cannot fathom. You are in good company, we are all monsters in civilized clothes; do not be insulted or ashamed.

Endeavor to be more.

Again.

Please.

John Chmelir (@JohnChmelir), Twitter (part of a 20-tweet thread), 2018-10-20.

March 28, 2021

TARIFFS and TAXES: The REAL Cause of the CIVIL WAR?!

Atun-Shei Films

Published 16 Jan 2020Checkmate, Lincolnites! Debunking the Lost Cause myth that the American Civil War was fought over taxes and protectionist tariffs. Was the South subjected to disproportionate taxation? Did the Morrill Tariff cause secession? Watch and find out, you no-account, yellow-bellied sesech!

Support Atun-Shei Films on Patreon ► https://www.patreon.com/atunsheifilms

Leave a Tip via Paypal ► https://www.paypal.me/atunsheifilms (All donations made here will go toward the production of The Sudbury Devil, our historical feature film)

Buy Merch ► teespring.com/stores/atun-shei-films

#CheckmateLincolnites #CivilWar #AmericanHistory

Reddit ► https://www.reddit.com/r/atunsheifilms

Twitter ► https://twitter.com/atun_shei

March 20, 2021

History RE-Summarized: The Age of Augustus

Overly Sarcastic Productions

Published 19 Mar 2021Many Romans had conquered the Republic, but nobody could keep it, until Augustus. In the half century after the assassination of Caesar, his adoptive son would fundamentally transform the Roman state: expanding it, reforming it, and bringing it under the control of one man. The Age of Augustus found Rome a Republic and left it an Empire.

This video is a Remastered, Definitive Edition of three previous videos from this channel — History Summarized: “Augustus Versus The Assassins”, “Augustus Versus Antony”, and “How Augustus Made An Empire”. This video combines them all into one narrative, fully upgrading all of the visuals and audio. If you want more Histories to be Re-Summarized, please comment and let me know!

SOURCES & Further Reading: The Age of Augustus by Werner Eck, Augustus and the Creation of the Roman Empire by Ronald Mellor, Cleopatra: A Life by Stacy Schiff, Virgil’s Aeneid, Polybius’ Histories, Livy’s Ab Urbe Condita, Plutarch’s Parallel Lives, SPQR by Mary Beard, Rome: A History in Seven Sackings by Matt Kneale, (and also my degree in Classical Studies).

SECTION TIME-CODES:

0:00 1 — Octavian V. the Assassins

07:40 2 — Octavian V. Antony

17:36 3 — Augustus as EmperorOur content is intended for teenage audiences and up.

PATREON: https://www.Patreon.com/OSP

PODCAST: https://overlysarcasticpodcast.transi…

DISCORD: https://discord.gg/osp

MERCH LINKS: http://rdbl.co/osp

OUR WEBSITE: https://www.OverlySarcasticProductions.com

Find us on Twitter https://www.Twitter.com/OSPYouTube

Find us on Reddit https://www.Reddit.com/r/OSP/

March 13, 2021

Confederate Soldiers DIDN’T Fight for SLAVERY!! (Or Did They?)

Atun-Shei Films

Published 20 Sep 2019Checkmate, Lincolnites! Debunking the Lost Cause myth that Johnny Reb, the common Confederate soldier, didn’t fight to preserve the institution of slavery.

Support Atun-Shei Films on Patreon ► https://www.patreon.com/atunsheifilms

Leave a Tip via Paypal ► https://www.paypal.me/atunsheifilms (All donations made here will go toward the production of The Sudbury Devil, our historical feature film)

Buy Merch ► teespring.com/stores/atun-shei-films

#CheckmateLincolnites #CivilWar #AmericanHistory

Reddit ► https://www.reddit.com/r/atunsheifilms

Twitter ► https://twitter.com/atun_shei

March 11, 2021

Boris as a latter-day Prince Rupert of the Rhine?

In The Critic, Graham Stewart portrays the British Prime Minister and Sir Keir Starmer, leader of Her Majesty’s loyal opposition in the House of Commons as English Civil War combatants:

King Charles I and Prince Rupert before the Battle of Naseby 14th June 1645 during the English Civil War.

19th century artist unknown, from Wikimedia Commons.

Prime Minister’s Questions distils into a single gladiatorial contest what thousands of enthusiasts in a charitable organisation called the Sealed Knot perform across the country most summers – namely the re-enactment of battles of the English Civil War.

Unsmiling, relentless, serious to the point of bringing despair to his foot-soldiers as much as his opponents, Sir Keir Starmer is a Roundhead general for our times. Nobody believes better than he that virtue and providence are his shield. This faith sustains him whilst the fickle and ungodly court of popular opinion fails to rally to his command. He believes that holding firm, doggedly probing the enemy with the long pike and short-sword will eventually prevail, no matter how long the march to victory may prove.

Facing him, the generous girth of the nation’s leading Cavalier occupies his command-post. His long, uncut hair resembling a thatch on a half-timbered cottage, Boris Johnson lands at the despatch box as if he has just fallen from his place of concealment in an oak tree, bleary and under-prepared, but confident in assertion. It might be said of him, as Sir Edward Bulwer Lytton once said of the parliamentary style of a previous Tory prime minister, Lord Derby, that Johnson is “irregularly great, frank, haughty, bold – the Rupert of debate.”

Today was one of those occasions when the prime minister did indeed resemble the dashing Prince Rupert of the Rhine. Unfortunately, it was the moment during the decisive civil war battle of Naseby when the great Cavalier commander charged his horsemen through the parliamentary lines with such momentum that they kept going and ended up spending the rest of the day plundering a distant baggage train rather than returning to determine the result of the battle.

March 10, 2021

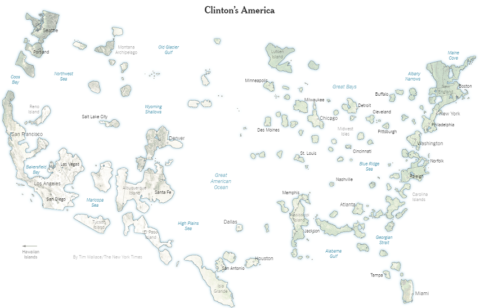

How wide is the gap between extreme partisanship and sectarian violence?

Sarah Hoyt says she really didn’t want to write this post, and I completely understand why she feels that way:

The next American Civil War will be fought in a lot of places, in sudden flare ups and unexpected bursts of rage. But where most casualties will occur is in the home.

America’s civil war will be fougnt many places, but mostly in living rooms: siblings against each other, parents against children, children against parents, husband against wife, wife against husband.

If you live with a convinced leftist, how safe is your life, should the balloon go up?

And before you say “The first civil war was also between brothers!”

Sure, it was. There were mixed families. Mostly upper crust mixed families. But the war was largely a regional war, the country riven on regional lines.

Now? Bah. Now it’s a war of ideology. A war of beliefs.

And a lot of people are sleeping with the enemy, hanging out on weekends with the enemy. Visiting the enemy. Having lunch with the enemy.

At this moment a lot of you are sitting back there and going “My wife/husband/elementary school friend is not an enemy. Sure, he/she/it drank the Marxist koolaid from a hose but in every day life, in our normal interactions, in non-political things, we are very close, the best of friends.”

And maybe you are. Maybe you can trust them with your life.

But I will remind you we live in a nation where the capital is surrounded with razor wire to defend themselves from people who voted for the guy. I will remind you there are troops occupying our capital and that our secret services have so far been corrupted they keep inventing internet conspiracies (or probably referring to their very own black ops) to justify it.

I will remind you that your favorite progressive has allowed himself to be moved from “strong welfare net” to “we need full on communism, with favored races” within the last 12 years (or was indoctrinated into that state in schools.) I will remind you — and the conversations related back to me don’t help me think otherwise — that your favorite leftist thinks you’re racist/homophobic/evil. NO MATTER HOW MANY indications to the contrary.

And I can hear you sniffling: “But I love him/her/it/fuzzy.” Well, yes, and ten years ago that would have been me. I had very good friends I just classed as political idiots. I don’t wish the last 10 years on anyone, but at least they’re not living with me, 90% of them don’t know where I live. And I’ll be out of here in hopefully no more than 4 but maybe ten months, and maybe we have that long. Also, most of my close friends/acquaintances aren’t likely to cause any damage, being … not the type. On the other hand two dozen of them (easy) are friends with people who WILL.

Now to be clear: do I expect all of you in mixed political families to be in danger?

No. Any number of your spouses, relatives and friends are leftist because that’s “what good people are.” And they will turn on a dime, too, if half the crap about what the left has been doing for the last couple of decades comes out unvarnished and unspun. (The left knows it too. They’re perhaps more scared of these people than they are of us.)

Others are leftist and might hate your guts if things go hot, but simply don’t have it in them to hurt anyone. These are the “slippery” ones, because if you had asked me, even two years ago, if the media and the left (BIRM) could spin these people into wishing death on someone for not wearing a mask, when the person is not sick; there’s no proof of asymptomatic transmission (there’s reports from China but NOWHERE ELSE); and the actual disease (it’s not hard to find) might be a little more lethal than the flu but only at ages past about 80, I’d have said “no. They’re politically insane, but not stupid.” However they are “group oriented.” Turns out the type of gaslighting we’ve been enduring works really well on people who live for others’ opinions. (Which explains whey Southern Europe is still mired in the fricking crazy. Uniformly. And why women in general are more susceptible to the completely irrational gaslighting than men.) And they already believe a bunch of crazy crap. The reason that they think QANON is right main stream, it’s because it’s the mirror image of their actual main stream.

Are you sure they’ll remain inoffensive if the ballon goes up and the gaslighting switches to “If you know a Trump voter, he/she is dangerous?” How about “Turn them in, so they can be sent somewhere nice for their own protection?”

Look, guys, I hope none of this is ever needed. I still have friends on the other side, I’m just not in touch and we work on the very long finger. And there are people I no longer consider friends but whom I like very much who are buying into the entire insane bull excreta of “attempted coup” and evil “white nationalists.”

But like Peter Grant, I think we’re way past the ballot box, and just waiting for a precipitating incident.

I desperately hope she’s wrong about this, because an actual shooting war in the United States would be a disaster for western civilization.

Update: It’s apparently time to Immanentize the Eschaton!

I’m of the firm opinion that the Progressive Left believed that once Obama won his second term they were set. The eschaton night not be immanent, but it was imminent. Hillary was going to be another “great leap forward” towards the heaven on Earth promised by Karl Marx. […]

“Politics” it is said, “is the art of compromise.” “War,” said von Clausewitz, “is politics by other means.” I have repeated and repeated the observation that has made itself manifest in the nearly 18 years I’ve been writing this blog: Charles Krauthammer noted in 2002 that “To understand the workings of American politics you have to understand this fundamental law: Conservatives think liberals are stupid. Liberals think conservatives are evil.”

You don’t debate with evil. You don’t negotiate with evil. You don’t compromise with evil. You don’t tolerate evil. You DESTROY evil. You pat it on the head until you can find a rock big enough to bash its skull in.

And control of the culture, education, and the government makes for a big damned rock.

Here’s the tinfoil yarmulke part of this essay: The preparations are underway. When debate and compromise are no longer possible, then force is the only thing left. They know it, and they’re projecting it on their enemy, us.

The Progressive Left has created and exercised its Sturmabteilung (yes, I know I risk Godwinization, and they loathe such comparisons, but this one’s apt. Their outfits are black instead of brown, but the actions are the same.) They’ve been set loose in the Pacific Northwest and some other cities and have been allowed to riot, commit arson, loot and occasionally murder with little to no legal consequence (violence, after all, being free speech you know.) Andy Ngo has studied Antifa, itself with roots in radical Socialism, in depth, and says that they are preparing for war, generously supported by the more mainstream Progressive Left. Black Lives Matter, an organization founded by two open Marxists, is also part of the preparations, but these are in my opinion just the Progressive Left’s “useful idiot” shock troops – the first to go against the wall after the Revolution.

February 27, 2021

January 16, 2021

Inside the Neurotic Mind of Stonewall Jackson

Atun-Shei Films

Published 15 Jan 2021Let’s gossip about a man who’s been dead for 158 years.

Support Atun-Shei Films on Patreon ► https://www.patreon.com/atunsheifilms

Leave a Tip via Paypal ► https://www.paypal.me/atunsheifilms

Buy Merch ► teespring.com/stores/atun-shei-films

#ThomasJJackson #CivilWar #AmericanHistory

Original Music by Dillon DeRosa ► http://dillonderosa.com/

Reddit ► https://www.reddit.com/r/atunsheifilms

Twitter ► https://twitter.com/atun_shei

~REFERENCES~[1] Wallace Hettle. Inventing Stonewall Jackson: A Civil War Hero in History and Memory (2011). LSU Press, Page 3-9

[2] Hettle, Page 13-17

[3] Charles Royster. The Destructive War: William Tecumseh Sherman, Stonewall Jackson, and the Americans (1991). Vintage Books, Page 41-46

[4] Royster, Page 52-53

[5] Hettle, Page 20-21

[6] Royster, Page 65-67

[7] Chris Graham. “Myths and Misunderstandings: Stonewall Jackson’s Sunday School” (2017). The American Civil War Museum https://acwm.org/blog/myths-misunders…

[8] Royster, Page 63-65

[9] Royster, Page 60

[10] Royster, Page 49-51

[11] Mary Anna Jackson. Memoirs of Stonewall Jackson by his Widow, Marry Anna Jackson (1895). Prentice Press, Page 108

[12] Jackson, Page 120-121

[13] Hettle, Page 13-15

[14] Royster, Page 202

January 6, 2021

The Use and Abuse of the US Postal System (feat. Mr. Beat)

The Cynical Historian

Published 10 Oct 2020Thanks to Private Internet Access for sponsoring this video. Click here to get 77% off and 3-months free: http://www.privateinternetaccess.com/…

We’ve been seeing a lot of coverage about the post office here in the United States. A lot of folks talk about the history of it, but generally in a piecemeal fashion. The fact most of this commentary lacks is that the post office has always been a political tool, from its beginnings even before the US Constitution. Interestingly enough, what it has been used for over the years has changed substantially, but it is always a harbinger of the up and coming dominant ideology. The post office is a cornerstone of our democracy. The postal system in the United States is uniquely important.

Check out Mr. Beat’s video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=favVdKa6cRQ

————————————————————

Connected videos:

3:30 – 1776 | Based on a True Story: https://youtu.be/xY4Te8Qm07A

9:15 – What caused the Mexican-American thing? https://youtu.be/HTmSN4Exci0

9:15 – What Caused the Texas Revolution? https://youtu.be/lDWH-DC74Pk

9:25 – California Gold Rush: https://youtu.be/W1dmyx6LBKA

9:30 – History of California: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list…

11:30 – The Sectional Crisis: https://youtu.be/Ff2AKILyi0o

14:05 – History of Voting by Mail: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=favVd…

18:25 – Trains and Oil in California: https://youtu.be/0Ef0Ir-hbFc

18:30 – The History of Early Flight: https://youtu.be/sPgxuD0uYYE

20:35 – US Veterans History: https://youtu.be/ANUqaNykuRs

————————————————————

references:

The United States Postal Service: An American History (Washington, DC: United States Postal Service, 2020). https://about.usps.com/publications/p… [PDF]USPS’s website has a trove of information on their history: https://about.usps.com/who-we-are/pos…

The national postal museum is run by the Smithsonian and includes numerous research articles available to anyone on their website: https://postalmuseum.si.edu/research-…https://www.nationalgeographic.com/hi…

————————————————————

Support the channel through PATREON:

https://www.patreon.com/CynicalHistorian

or by purchasing MERCH: teespring.com/stores/the-cynical-hist…

LET’S CONNECT:

Discord: https://discord.gg/Ukthk4U

Twitter: https://twitter.com/Cynical_History

Subreddit: https://www.reddit.com/r/CynicalHistory/————————————————————

Wiki: The United States Postal Service (USPS; also known as the Post Office, U.S. Mail, or Postal Service) is an independent agency of the executive branch of the United States federal government responsible for providing postal service in the United States, including its insular areas and associated states. It is one of the few government agencies explicitly authorized by the United States Constitution.

The USPS traces its roots to 1775 during the Second Continental Congress, when Benjamin Franklin was appointed the first postmaster general. The Post Office Department was created in 1792 with the passage of the Postal Service Act. It was elevated to a cabinet-level department in 1872, and was transformed by the Postal Reorganization Act of 1970 into the United States Postal Service as an independent agency. Since the early 1980s, many direct tax subsidies to the USPS (with the exception of subsidies for costs associated with disabled and overseas voters) have been reduced or eliminated.

————————————————————

Hashtags: #history #USPS #USMail

December 17, 2020

Merrill Breechloading Conversion of the 1841 Mississippi Rifle

Forgotten Weapons

Published 9 Sep 2020http://www.patreon.com/ForgottenWeapons

https://www.floatplane.com/channel/Fo…

Cool Forgotten Weapons merch! http://shop.bbtv.com/collections/forg…

James Merrill of Baltimore had his hand in several Civil War era firearms — rifles built from scratch, conversions of the Jenks carbines, and also conversions of 1841 Mississippi rifles done by the Harpers Ferry Arsenal. Merrill’s conversion involved a knee-joint type lever which could be opened to allow loading of a rifle from the breech. The system was relatively simple, and it was one of three (the others were the Lindner and Montstorm) made in small numbers for testing by Harpers Ferry. It appears that 300 Merrill conversions were done, 100 each of the 1841 Mississippi Rifle, 1842 musket, and 1847 musketoon.

Contact:

Forgotten Weapons

6281 N. Oracle #36270

Tucson, AZ 85740

December 11, 2020

QotD: Airbrushing out the worst parts of “Lost Cause” mythology

The South could have become a running sore, a cauldron of low-level insurrection and guerilla warfare that blighted the next century of U.S. history. Instead, it is now the most patriotic region of the U.S. – as measured, for example, by regional origins of U.S. military personnel. How did this happen?

Looking back, we can see that between 1865 and around 1914 the Union and the former South negotiated an imperfect but workable peace. The first step in that negotiation took place at Appomattox, when the Union troops accepting General Robert E. Lee’s surrender saluted the defeated and allowed them to retain their arms, treating them with the most punctilious military courtesy due to honorable foes.

Over the next few years, the Union Army reintegrated the Confederate military into itself. Confederate officers not charged with war crimes were generally able to retain rank and seniority; many served in the frontier wars of the next 35 years. Elements of Confederate uniform were adopted for Western service.

The political leaders of the revolt were not executed. Instead, they were spared to urge reconciliation, and generally did. By all historical precedent they were treated with shocking leniency. This paid off.

Of course, not all went smoothly. The Reconstruction of the South between 1863 and 1877 was badly bungled, creating resentments that linger to this day and – in the folk memory of Southerners – often overshadow the harms of the war itself. The condition of emancipated blacks remained dire.

But overall, the reintegration of the South went far better than it could have. Confederate nationalism was successfully reabsorbed into American nationalism. One of the prices of this adjustment was that Confederate heroes had to become American heroes. An early and continuing example of this was the reverence paid to Robert E. Lee by Unionists after the war; his qualities as a military leader were extolled and his opposition to full civil rights for black freedmen memory-holed.

Lee’s heroism and ascribed saintliness would layer become a central prop in “Lost Cause” romanticism, which portrayed the revolt as an honorable struggle for a Southern way of life while mostly airbrushing out – but sometimes, unforgiveably, defending – the institution of slavery. Even today, the “soft” airbrushing version of Lost Cause retains a significant hold on Southerners who would never dream of defending slavery.

Eric S. Raymond, “Unlearning history”, Armed and Dangerous, 2017-09-22.