Chris Bray is reading a book by Tim Reiterman which goes into great detail about the life and career of cult leader and mass murderer Jim Jones:

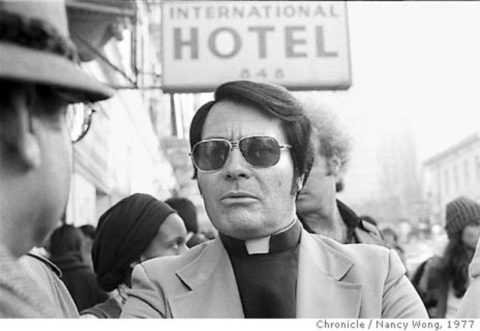

Reverend Jim Jones in front of the International Hotel in San Francisco’s Chinatown on Kearny & Jackson Streets during a rally to save the hotel.

San Francisco Chronicle photo by Nancy Wong, 1977 via Wikimedia Commons.

In 1971, Jim Jones loaded up some buses in California and took members of his Peoples Temple across the country to Pennsylvania — to Woodmont, the estate of the late spiritual leader Father Divine, who had a much bigger church (and a lot more money) than Jones did.

Reaching Woodmont, Jones tried Plan A, announcing the glorious news that he was the reincarnation of Father Divine and had come to lead his church again, and we might as well just go ahead and put my name on all the bank accounts; the dead leader’s wife suggested, in fairly clear language, that Jones get back on his bus while he could still walk. The delegation from Peoples Temple took the hint. But Jones also executed Plan B, with modest success: He poached some congregants, and drove them across the country to his own church in Ukiah.

Back home, Jones worried that people who had followed Father Divine would struggle to make the transition, feeling more loyalty to their old leader than to their new one. So he showed them that he couldn’t be crossed. One day, as the refugees from Philadelphia sat eating a meal with everyone else in the communal dining room, Jones walked in and caught several of the earlier members of his church being disloyal to him — and so, pointing a finger, he ordered them to die.

They did, immediately. Bodies littered the floor. Jones let the silence linger, standing over the lifeless bodies of the people who had betrayed his trust, the power of death shooting through his fingertips. And then he showed his merciful side: He resurrected them, a choice that allowed the dead to share the horrible feeling of being struck down by the indescribably vast and awesome power of Jim Jones. Terrified, the new members of the church fell into line.

He did this shit all the time. During recruiting trips to rented churches in other cities, visitors had mid-sermon strokes and heart attacks; nurses in the congregation frantically tried to resuscitate them, but announced that it was too late. But no, the Reverend Jones wouldn’t allow death to strike in his own holy church! Rushing forward and shoving the nurses aside, he commanded the dead to ARISE, ARIIIIISSSSEEE yadda yadda whatever. In 1972, a church bulletin proudly announced that Jones had personally resurrected forty dead people so far in just that one year. And here you are feeling proud that you remembered to make the bed this morning.

I take these stories from Raven, a doorstop-thick history of Jones and Peoples Temple written by the journalist Tim Reiterman (with research assistance from a colleague, John Jacobs). Reiterman decided to write about Jones after he was shot at Jonestown, visiting the final Peoples Temple location with the congressional delegation led by Leo Ryan. The research task was made easier by the self-regard the Reverend Jones had felt, because he left behind a giant catalogue of taped sermons and lectures, and a long paper trail of church bulletins and memoranda. The resulting book is an extraordinarily detailed look at every step Jones took along the path to mass murder, starting with the sadistic hucksterism of his strange childhood.

Original artwork by Miłek Jakubiec

Original artwork by Miłek Jakubiec  Recommended reading (as an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases):

Recommended reading (as an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases): Procopius, History of the Wars

Procopius, History of the Wars  Buy EHTV t-shirts, hoodies, mugs and stickers here! teespring.com/en-GB/stores/epic-histo…

Buy EHTV t-shirts, hoodies, mugs and stickers here! teespring.com/en-GB/stores/epic-histo… Music from Filmstro:

Music from Filmstro: