Herbert Hoover spent his entire presidency miserable.

First, he has no doubt that the economy is going to crash. It’s been too good for too long. He frantically tries to cool down the market, begs moneylenders to stop lending and bankers to stop banking. It doesn’t work, and the Federal Reserve is less concerned than he is. So he sits back and waits glumly for the other shoe to drop.

Second, he hates politics. Somehow he had thought that if he was the President, he would be above politics and everyone would have to listen to him. The exact opposite proves true. His special session of Congress comes up with the worst, most politically venal tariff bill imaginable. Each representative declares there should be low tariffs on everything except the products produced in his own district, then compromises by agreeing to high tariffs on everything with good lobbyists. The Senate declares that the House of Representatives is corrupt nincompoops and sends the bill back in disgust. Hoover has no idea how to solve this problem except to ask the House to do some kind of rational economically-correct calculation about optimal tariffs, which the House finds hilarious. “Opposed to the House bill and divided against itself, the Senate ran out the remaining seven weeks [of the special session] in a debauch of taunts, accusations, recriminations, and procedural argument.” The public blames Hoover, pretty fairly – a more experienced president would have known how to shepherd his party to a palatable compromise.

Also, there are crime waves, prison riots, bootlegging, and a heat wave during which Washington DC is basically uninhabitable. Also, at one point the White House is literally on fire.

… and then the market finally crashes. Hoover is among the first to call it a Depression instead of a Panic – he thinks the new term might make people panic less. But in fact, people aren’t panicking. They assume Hoover has everything in hand.

At first he does. He gathers the heads of Ford, Du Pont, Standard Oil, General Electric, General Motors, and Sears Roebuck and pressures them to say publicly they won’t fire people. He gathers the AFL and all the union heads and pressures them to say publicly they won’t strike. He enacts sweeping tax cuts, and the Fed enacts sweeping rate cuts. Everyone is bedazzled […] Six months later, employment is back to its usual levels, the stock market is approaching its 1929 level, and Democrats are fuming because they expect Hoover’s popularity to make him unbeatable in the midterms. I got confused at this point in the book – did I accidentally get a biography from an alternate timeline with a shorter, milder Great Depression? No – this would be the pattern throughout the administration. Hoover would take some brilliant and decisive action. Economists would praise him. The economy would start to look better. Everyone would declare the problem solved – especially Hoover, sensitive both to his own reputation and to the importance of keeping economic optimism high. Then the recovery would stall, or reverse, or something else would go wrong.

People are still debating what made the Great Depression so long and hard. Whyte’s theory, insofar as he has one at all, is “one thing after another”. Every time the economy started to go up (thanks to Hoover), there was another shock. Most of them involved Europe – Germany threatening to default on its debts, Britain going off the gold standard. A few involved the US – the Federal Reserve made some really bad calls. The one thing Whyte is really sure about is that his idol Herbert Hoover was totally blameless.

He argues that Hoover’s bank relief plan could have stopped the Depression in its tracks – but that Congressional Democrats intent on sabotaging Hoover forced the plan to publicize the names of the banks applying. The Democrats hoped to catch Hoover propping up his plutocrat friends – but the change actually had the effect of making banks scared to apply for funding and panicking the customers of banks that were known to have applied. He argues that the “Hoover Holiday” – a plan to grant debt relief to Germany, taking some pressure off the clusterf**k that was Europe – was a masterstroke, but that France sabotaged it in the interests of bleeding a few more pennies from its arch-rival. International trade might have sparked a recovery – except that Congress finally passed the Hawley-Smoot Tariff, the end result of the corruption-plagued tariff negotiations, just in time to choke it off.

Whyte saves his barbs for the real villain: FDR. If the book is to be believed, Hoover actually had things pretty much under control by 1932. Employment was rising, the stock market was heading back up. FDR and his fellow Democrats worked to tear everything back down so he could win the election and take complete credit for the recovery. The wrecking campaign entered high gear after FDR won in 1932; he was terrified that the economy might get better before he took office, and used his President-Elect status to hint that he was going to do all sorts of awful things. The economy got skittish again and obediently declined, allowing him to get inaugurated at the precise lowest point and gain the credit for recovery he so ardently desired.

Scott Alexander, “Book Review: Hoover”, Slate Star Codex, 2020-03-17.

March 23, 2025

QotD: Herbert Hoover as president

March 3, 2025

All The Basics About XENOPHON

MoAn Inc.

Published 7 Nov 2024I actually found this video really tricky considering I want to go into the texts of Xenophon and if I told you everything about the march of the ten thousand then I would have just told you the whole Anabasis?? Which defeats the whole purpose of an introductory video?? So I PROMISE more clarity will come in future videos as Xenophon himself breaks down his journey home from Persia and why they were there in the first place. Therefore, you have ALL OF THAT to look forward to — coming soon!!!

(more…)

February 14, 2025

Henry VIII, Lady Killer – History Hijinks

Overly Sarcastic Productions

Published 3 Feb 2023brb I’m blaring “Haus of Holbein” from Six the Musical on the loudest speakers I own.

SOURCES & Further Reading:

Britannica “Henry VIII” (https://www.britannica.com/biography/…, History “Who Were The Six Wives of Henry VIII” (https://www.history.com/news/henry-vi…), The Great Courses lectures: “Young King Hal – 1509-27”, “The King’s Great Matter – 1527-30”, “The Break From Rome – 1529-36”, “A Tudor Revolution – 1536-47”, and “The Last Years of Henry VIII – 1540-47” from A History of England from the Tudors to the Stuarts by Robert Bucholz

(more…)

February 8, 2025

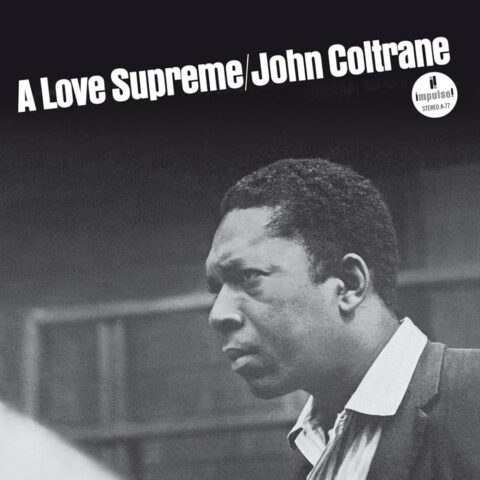

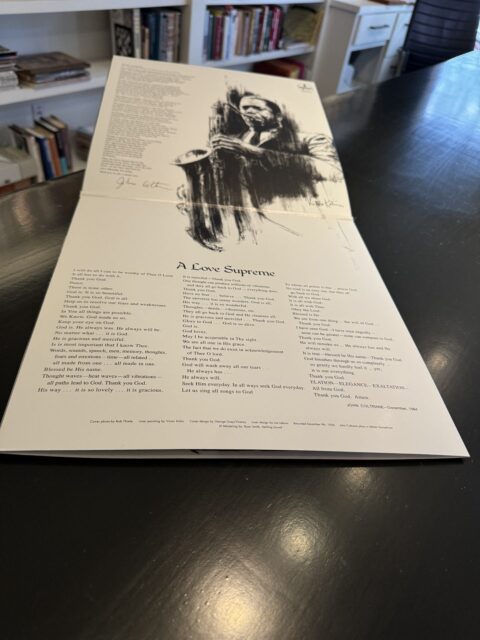

A Love Supreme after 60 years

John Coltrane’s A Love Supreme was one of the first four jazz albums I ever bought. It quickly became my favourite and led me to listening to a lot more of Coltrane’s work. Some I loved nearly as much (Giant Steps, Blue Train, The Complete Africa/Brass Sessions) while others I just bounced off (Sun Ship, Interstellar Space, Stellar Regions), but most became fixtures of my various jazz playlists.

Ted Gioia notes the moment as A Love Supreme hits 60 years after release:

Ivy League theoretical physicist Stephon Alexander will even tell you that John Coltrane has a lot in common with Albert Einstein. People still consult the saxophonist’s mathematical analysis — the so-called Coltrane Circle — as if it were a source of esoteric wisdom.

But in 1964, John Coltrane was also a father. John Coltrane Jr. was born on August 26, 1964 — the first of his three children. Ravi Coltrane arrived in 1965, and Oran in 1967.

You wouldn’t think that Coltrane could find time for anything else at the close of the Summer of 1964. But he did.

At that juncture, he disappeared into an upstairs guest room at his home. And spent day after day with just a pen, some paper, and his horn.

He emerged five days later. “It was like Moses coming down from the mountain,” Alice later recalled. “It was so beautiful. He walked down and there was that joy, that peace in his face, tranquility.”

“This is the first time that I have received all of the music for what I want to record,” he told her.

Note that word: Received. He didn’t say composed. He didn’t say created. It was a gift from something larger than himself.

This was the music John Coltrane would perform in the studio three months later. It’s know today as A Love Supreme.

Coltrane said that his music was his gift back to the Divine.

He made that clear in his liner notes, which opened with an invocation in capital letters: DEAR LISTENER: ALL PRAISE BE TO GOD TO WHOM ALL PRAISE IS DUE…

But if there were still any doubt, Coltrane also included a devotional poem — which began:

I will do all I can to be worthy of Thee O Lord.

It all has to do with it.

Thank you God.

Peace …Needless to say, this was not typical for jazz liner notes in the mid-1960s. Or at any time, for that matter.

And it almost certainly would limit sales — or so the conventional wisdom went back then. A few months later, Capitol Records execs had a meltdown when Brian Wilson wanted to give the name “God Only Knows” to a song. But that was nothing compared to the full-blown ritual that Coltrane was now unleashing on the hip jazz audience.

I use the word ritual advisedly here. I’ve heard other people describe A Love Supreme as a suite, but they’re missing the whole point. I have no doubt that Coltrane intended this ritualistic effect.

He even starts chanting toward the end of the opening track.

This was first time Coltrane’s voice had ever been featured on a studio recording. And he didn’t sing a love song or belt out a blues. Instead he was chanting:

A love supreme

A love supreme

A love supreme

A love supreme

A love supreme …He chants that phrase nineteen times in a row.

January 28, 2025

QotD: Was Einstein a science-denier?

Albert Einstein was a charmingly blunt man. For instance, in 1952 he wrote a letter to his friend and fellow physicist Max Born where he admits that even if the astronomical data had gone against general relativity, he would still believe in the theory:

Even if there were absolutely no light deflection, no perihelion motion and no redshift, the gravitational equations would still be convincing because they avoid the inertial system … It is really quite strange that humans are usually deaf towards the strongest arguments, while they are constantly inclined to overestimate the accuracy of measurement.

In a few short sentences Einstein completely repudiates the empiricist spirit which has ostensibly guided scientific inquiry since Francis Bacon. He doesn’t care what the data says. If the experiment hadn’t been run, he would still believe the theory. Moreover, should the data have disconfirmed his theory, who cares? Data are often wrong.

This is not, to put it mildly, the official story of how science gets made. In the version most of us were taught, the process starts with somebody noticing patterns or regularities in experimental data. Scientists then hypothesize laws, principles, and causal mechanisms that abstract and explain the observed patterns. Finally, these hypotheses are put to the test by new experiments and discarded if they contradict their results. Simple, straightforward, and respectful of official pieties. The Schoolhouse Rock of science. Or as Einstein once described it:

The simplest idea about the development of science is that it follows the inductive method. Individual facts are chosen and grouped in such a way that the law, which connects them, becomes evident. By grouping these laws more general ones can be derived until a more or less homogeneous system would have been created for this set of individual facts.

See? It’s as easy as that. But then, Einstein finishes that thought with: “[t]he truly great advances in our understanding of nature originated in a manner almost diametrically opposed to induction”.

Was Einstein a science-denier? I’m obviously kidding, but this is still pretty jarring stuff to read. How did he get this way? Einstein’s Unification is the story of the evolution of Einstein’s philosophical views, disguised as a story about his discovery of general relativity and his quixotic attempts at a unified field theory. It’s a gripping tale about how Einstein tried to do science “correctly”, experienced years of frustration, almost had priority for his discoveries snatched away from him, then committed some Bad Rationalist Sins at which point things immediately began to work. This experience changed him profoundly, and maybe it should change us too.

John Psmith, “REVIEW: Einstein’s Unification, by Jeroen van Dongen”, Mr. and Mrs. Psmith’s Bookshelf, 2024-05-27.

January 27, 2025

The Rise of Augustus – The Conquered And The Proud 12

Adrian Goldsworthy. Historian and Novelist

Published 4 Sept 2024Continiung the series “The Conquered and the proud”, we come to the early days of the young Octavian, the man who would become Caesar Augustus and found the Principate, the rule of emperors — a system that would last for centuries and see the Roman empire reach the pinnacle of its prosperity and population.

Just eighteen years old when Julius Caesar was murdered, his great nephew was named as principal heir in his will. This mean that he took his name and the bulk of his property. However, this ambitious teenager took it to mean that he should also succeed to Caesar’s power. Incredibly, after fourteen years of bloody struggle, he did just that.

January 16, 2025

Augustus and the Roman Army – the first emperor and the creation of the professional army

Adrian Goldsworthy. Historian and Novelist

Published 7 Aug 2024We take a look at Caesar Augustus, the first emperor (or princeps) of Rome and the great nephew of Julius Caesar. Ancient sources — and Shakespeare and Hollywood — depict him as politician and no soldier in contrast to Mark Antony. How true is this? More importantly, how did the man who created the imperial system and re-shaped society change the Roman army?

This video is based on a talk I gave in 2014 at the Roman Legionary Museum in Caerleon — a museum and adjacent sites, well worth a visit for anyone in or near South Wales.

January 13, 2025

The Writings of Cicero – Cicero and the Power of the Spoken Word

seangabb

Published 25 Aug 2024This lecture is taken from a course I delivered in July 2024 on the Life and Writings of Cicero. It covers these topics:

• Introduction – 00:00:00

• The Deficiencies of Modern Oratory – 00:01:20

• The Greeks and Oratory – 00:06:38

• Athens: Government by Lottery and Referendum – 00:08:10

• The Power of the Greek Language – 00:17:41

• The General Illiteracy of the Ancients – 00:21:06

• Greek Oratory: Lysias, Gorgias, Demosthenes – 00:28:38

• Macaulay as Speaker – 00:34:44

• Attic and Asianic Oratory – 00:36:56

• The Greek Conquest of Rome – 00:39:26

• Roman Oratory – 00:43:23

• Cicero: Early Life – 00:43:23

• Cicero in Greece – 00:46:03

• Cicero: Early Legal Career – 00:46:03

• Cicero: Defence of Roscius – 00:47:49

• Cicero as Orator (Sean Reads Latin) – 00:54:45

• Government of the Roman Empire – 01:01:16

• The Government of Sicily – 01:03:58

• Verres in Sicily – 01:06:54

• The Prosecution of Verres – 01:11:20

• Reading List – 01:24:28

(more…)

January 12, 2025

QotD: Kaiser Wilhelm II

Following the all-too brief reign of Frederick III, his son Wilhelm II, grandson of the first German Emperor, took power in 1888 (known as the “year of the three emperors”). From the start, the young Wilhelm was determined not to be the reserved figure of his grandfather and still less the liberal reformer that his ill-fated father had wished to be. Instead, Wilhelm believed it was his right and duty to be directly involved in the country’s governing.

This was completely incompatible with Bismarck’s system, which had centralized power upon his own person. With uncharacteristic focus and subtlety, Wilhelm sought to reclaim the power that his grandfather had ceded to the chancellor. This was not to prove especially difficult; Bismarck’s position had always relied upon his indispensability to the emperor. Thus, when Bismarck offered his resignation (as he often did during disputes) Wilhelm merely accepted it. The last great man of the wars of unification had now disappeared from the balance.

While the German Empire never became a true autocracy, Wilhelm succeeded in creating what historian, and biographer of the Kaiser, John C. Röhl called a “personalist” system.1 The Kaiser had significant power over personnel. Promotions in the officer corps required his assent. Advancement within civil service (from which civilian ministers were appointed) was also dependent on his favor. By exercising this power, Wilhelm was able to ensure the highest levels of the German government were men agreeable to his point of view. Though they were not mere “yes men”, Wilhelm ensured that they were knowingly dependent on his favor for their position. The Kaiser — even to the end of the monarchy — exercised considerable “negative power” (as Röhl termed it.)2 While Wilhelm’s ability to actively make policy was limited, anything he disapproved of was simply not proposed.

Wilhelm II’s reign marked a departure from the more restrained leadership of his predecessors, as he sought to assert direct influence over the German Empire’s governance and military affairs. This shift toward a more “personalist” system, where loyalty to the Kaiser outweighed true statesmanship, weakened the effectiveness of German leadership and contributed to its eventual strategic missteps. The rigid adherence to the Schlieffen Plan and the technocratic focus on material advantages, such as firepower and mobility, overshadowed the need for adaptable strategic thinking. These failures in both leadership and military planning set the stage for Germany’s disastrous involvement in World War I, where an empire led by personalities rather than policies was ill-prepared for the complexities of modern warfare. Ultimately, Wilhelm’s influence and the culture of sycophancy he fostered played a pivotal role in leading Germany down the path of ruin.

Kiran Pfitzner and Secretary of Defense Rock, “The Kaiser and His Men: Civil-Military Relations in Wilhelmine Germany”, Dead Carl and You, 2024-10-02.

1. John C. G. Röhl, Kaiser Wilhelm II: A Concise Life (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 2014).

2. Negative power refers to the ability of an actor or group to block, veto, or prevent actions, decisions, or policies from being implemented, rather than directly initiating or shaping outcomes.

January 7, 2025

Caesar’s dictatorship and the Ides of March – The Conquered And The Proud 11

Adrian Goldsworthy. Historian and Novelist

Published 31 Jul 2024Continuing “The conquered and the proud”, this time we look at Julius Caesar as dictator in Rome, about his activities and reforms and his murder on the 15th March — The Ides of March — in 44 BC. We talk about Brutus, Cassius and the other conspirators and what motivated them.

December 29, 2024

QotD: Churchill as author and Prime Minister

“Writing a book is an adventure. To begin with it is a toy, an amusement; then it becomes a mistress, and then a master, and then a tyrant.” Those owning a business plan, devising an advertising proposal, plotting a military stratagem, drafting an architectural blueprint, painting a picture, crafting sculpture or ceramics, penning a volume, sermon or speech — or editing The Critic — will, I suspect, be nodding in recognition of this.

The words were those of Winston Churchill, the 150th anniversary of whose birthday, 30 November 1874, falls this year. In addition to submitting canvases to the Royal Academy of Arts under the pseudonym David Winter — which resulted in his election as Honorary Academician in 1948 — and twice being Prime Minister for a total of eight years and 240 days, he has merited far more biographies than all his predecessors and successors put together. This summer I completed one more volume to add to the vast collection. My purpose here is less to blow my own trumpet than to ponder why Churchill remains so popular as a subject and survey what is new in print for this anniversary year.

It is tempting to see his career through many different lenses, for his achievements during a ninety-year lifespan spanning six monarchs encompassed so much more than politics, including that of painter. The only British premier to take part in a cavalry charge under fire, at Omdurman on 2 September 1898, he was also the first to possess an atomic weapon, when a test device was detonated in Western Australia on 3 October 1952. Besides being known as an animal breeder, aristocrat, aviator, big-game hunter, bon viveur, bricklayer, broadcaster, connoisseur of cigars and fine fines (his preferred Martini recipe included Plymouth gin and ice, “supplemented with a nod toward France”), essayist, gambler, global traveller, horseman, journalist, landscape gardener, lepidopterist, monarchist, newspaper editor, Nobel Prize-winner, novelist, orchid-collector, parliamentarian, polo player, prison escapee, public schools fencing champion, rose-grower, sailor, soldier, speechmaker, statesman, war correspondent, war hero, warlord and wit, one of his many lives was that of writer-historian.

Most of his long life revolved around words and his use of them. Hansard recorded 29,232 contributions made by Churchill in the Commons; he penned one novel, thirty non-fiction books, and published twenty-seven volumes of speeches in his lifetime, in addition to thousands of newspaper despatches, book chapters and magazine articles. Historically, much understanding of his time is framed around the words he wrote about himself. “Not only did Mr. Churchill both get his war and run it: he also got in the first account of it” was the verdict of one writer, which might be the wish of many successive public figures. Acknowledging his rhetorical powers, which set him apart from all other twentieth century politicians, his patronymic has gravitated into the English language: Churchillian resonates far beyond adherence to a set of policies, which is the narrow lot of most adjectival political surnames.

“I have frequently been forced to eat my words. I have always found them a most nourishing diet”, Churchill once quipped at a dinner party, and on another occasion, “history will be kind to me for I intend to write it”. Yet “Winston” and “Churchill” are the words of a conjuror, that immediately convey a romance, a spell, and wonder that one man could have achieved so much. It is an enduring magic, and difficult to penetrate. In 2002, by way of example, he was ranked first in a BBC poll of the 100 Greatest Britons of All Time — amongst many similar accolades. A less well-known survey of modern politics and history academics conducted by MORI and the University of Leeds in November 2004 placed Attlee above Churchill as the 20th Century’s most successful prime minister in legislative terms — but he was still in second place of the twenty-one PMs from Salisbury to Blair.

Peter Caddick-Adams, “Reading Winston Churchill”, The Critic, 2024-09-22.

December 6, 2024

QotD: Herbert Hoover in the Harding and Coolidge years

[Herbert] Hoover wants to be president. It fits his self-image as a benevolent engineer-king destined to save the populace from the vagaries of politics. The people want Hoover to be president; he’s a super-double-war-hero during a time when most other leaders have embarrassed themselves. Even politicians are up for Hoover being president; Woodrow Wilson has just died, leaving both Democrats and Republicans leaderless. The situation seems perfect.

Hoover bungles it. He plays hard-to-get by pretending he doesn’t want the Presidency, but potential supporters interpret this as him just literally not wanting the Presidency. He refuses to identify as either a Democrat or Republican, intending to make a gesture of above-the-fray non-partisanship, but this prevents either party from rallying around him. Also, he might be the worst public speaker in the history of politics.

Warren D. Harding, a nondescript Senator from Ohio, wins the Republican nomination and the Presidency. Hoover follows his usual strategy of playing hard-to-get by proclaiming he doesn’t want any Cabinet positions. This time it works, but not well: Harding offers him Secretary of Commerce, widely considered a powerless “dud” position. Hoover accepts.

Harding is famous for promising “return to normalcy”, in particular a winding down of the massive expansion of government that marked WWI and the Wilson Administration. Hoover had a better idea – use the newly-muscular government to centralize and rationalize American In his first few years in Commerce – hitherto a meaningless portfolio for people who wanted to say vaguely pro-prosperity things and then go off and play golf – Hoover instituted/invented housing standards, traffic safety standards, industrial standards, zoning standards, standardized electrical sockets, standardized screws, standardized bricks, standardized boards, and standardized hundreds of other things. He founded the FAA to standardize air traffic, and the FCC to standardize communications. In order to learn how his standards were affecting the economy, he founded the NBER to standardize government statistics.

But that isn’t enough! He mediates a conflict between states over water rights to the Colorado River, even though that would normally be a Department of the Interior job. He solves railroad strikes, over the protests of the Department of Labor. “Much to the annoyance of the State Department, Hoover fielded his own foreign service.” He proposes to transfer 16 agencies from other Cabinet departments to the Department of Commerce, and when other Secretaries shot him down, he does all their jobs anyway. The press dub him “Secretary of Commerce and Undersecretary Of Everything Else”.

Hoover’s greatest political test comes when the market crashes in the Panic of 1921. The federal government has previously ignored these financial panics. Pre-Wilson, it was small and limited to its constitutional duties – plus nobody knows how to solve a financial panic anyway. Hoover jumps into action, calling a conference of top economists and moving forward large spending projects. More important, he is one of the first government officials to realize that financial panics have a psychological aspect, so he immediately puts out lots of press releases saying that economists agree everything is fine and the panic is definitely over. He takes the opportunity to write letters saying that Herbert Hoover has solved the financial panic and is a great guy, then sign President Harding’s name to them. Whether or not Hoover deserves credit, the panic is short and mild, and his reputation grows.

While everyone else obsesses over his recession-busting, Hoover’s own pet project is saving the Soviet Union. Several years of civil war, communism, and crop failure have produced mass famine. Most of the world refuses to help, angry that the USSR is refusing to pay Czarist Russia’s debts and also pretty peeved over the whole Communism thing. Hoover finds $20 million to spend on food aid for Russia, over everyone else’s objection […]

So passed the early 1920s. Warren Harding died of a stroke, and was succeeded by Vice-President “Silent Cal” Coolidge, a man famous for having no opinions and never talking. Coolidge won re-election easily in 1924. Hoover continued shepherding the economy (average incomes will rise 30% over his eight years in Commerce), but also works on promoting Hooverism, his political philosophy. It has grown from just “benevolent engineers oversee everything” to something kind of like a precursor modern neoliberalism:

Hoover’s plan amounted to a complete refit of America’s single gigantic plant, and a radical shift in Washington’s economic priorities. Newsmen were fascinated by is talk of a “third alternative” between “the unrestrained capitalism of Adam Smith” and the new strain of socialism rooting in Europe. Laissez-faire was finished, Hoover declared, pointing to antitrust laws and the growth of public utilities as evidence. Socialism, on the other hand, was a dead end, providing no stimulus to individual initiative, the engine of progress. The new Commerce Department was seeking what one reporter summarized as a balance between fairly intelligent business and intelligently fair government. If that were achieved, said Hoover, “we should have given a priceless gift to the twentieth century.”

Scott Alexander, “Book Review: Hoover”, Slate Star Codex, 2020-03-17.

December 5, 2024

QotD: Oscar Wilde

That story, I need scarcely say, is anything but edifying. One rises from it, indeed with the impression that the misdemeanor which caused Wilde’s actual downfall was quite the least of his onslaughts upon the decencies — that he was of vastly more ardor and fluency as a cad and poltroon than ever he became as an immoralist. No offense against what the average civilized man regards as proper and seemly conduct is missing from the chronicle. Wilde was a fop and a snob, a toady and a social pusher, a coward and an ingrate, a glutton and a grafter, a plagiarist and a mountebank; he was jealous alike of his superiors and of his inferiors; he was so spineless that he fell an instant victim to every new flatterer; he had no sense whatever of monetary obligation or even of the commonest duties of friendship; he lied incessantly to those who showed him most kindness, and tried to rob some of them; he seems never to have forgotten a slight or remembered a favour; he was as devoid of any notion of honour as a candidate for office; the moving spring of his whole life was a silly and obnoxious vanity. It is almost impossible to imagine a fellow of less ingratiating character, and to these endless defects he added a physical body that was gross and repugnant, but through it all ran an incomparable charm of personality, and supporting and increasing that charm was his undoubted genius. Harris pauses more than once to hymn his capacity for engaging the fancy. He was a veritable specialist in the amenities, a dinner companion sans pair, the greatest of English wits since Congreve, the most delightful of talkers, an artist to his finger-tips, the prophet of a new and lordlier aesthetic, the complete antithesis of English stodginess and stupidity.

H.L. Mencken, “Portrait of a Tragic Comedian”, The Smart Set, 1916-09.

November 30, 2024

Forgotten War Ep 5 – Chindits 2 – The Empire Strikes

HardThrasher

Published 29 Nov 202402:00 – Here We Go Again

06:36 – Perfect Planning

13:16 – Death of a Prophet

14:51 – The Fly In

18:56 – Dazed and Confused (in the Monsoon)

20:40 – Can’t Fly in This

31:54 – Survivor’s ClubPlease consider donations of any size to the Burma Star Memorial Fund who aim to ensure remembrance of those who fought with, in and against 14th Army 1941–1945 — https://burmastarmemorial.org/

(more…)

November 18, 2024

QotD: Napoleon and his army

To me the central paradox of Napoleon’s character is that on the one hand he was happy to fling astonishing numbers of lives away for ultimately extremely stupid reasons, but on the other hand he was clearly so dedicated to and so concerned with the welfare of every single individual that he commanded. In my experience both of leading and of being led, actually giving a damn about the people under you is by far the most powerful single way of winning their loyalty, in part because it’s so hard to fake. Roberts repeatedly shows us Napoleon giving practically every bit of his life-force to ensure good treatment for his soldiers, and they reward him with absolutely fanatical devotion, and then … he throws them into the teeth of grapeshot. It’s wild.

Napoleon’s easy rapport with his troops also gives us some glimpses of his freakish memory. On multiple occasions he chats with a soldier for an hour, or camps with them the eve before a battle; and then ten years later he bumps into the same guy and has total recall of their entire conversation and all of the guy’s biographical details. The troops obviously went nuts for this kind of stuff. It all sort of reminds me of a much older French tradition, where in the early Middle Ages a feudal lord would (1) symbolically help his peasants bring in the harvest and (2) literally wrestle with his peasants at village festivals. Back to your point about the culture, my anti-egalitarian view is that that kind of intimacy across a huge gulf of social status is easiest when the lines of demarcation between the classes are bright, clear, and relatively immovable. What’s crazy about Napoleon, then, is that despite him being the epitome of the arriviste he has none of the snobbishness of the nouveaux-riches, but all of the easy familiarity of the natural aristocrat.

True dedication to the welfare of those under your command,1 and back-slapping jocularity with the troops, are two of the attributes of a wildly popular leader. The third2 is actually leading from the front, and this was the one that blew my mind. Even after he became emperor, Napoleon put himself on the front line so many times he was practically asking for a lucky cannonball to end his career. You’d think after the fourth or fifth time a horse was shot out from under him, or the guy standing right next to him was obliterated by canister shot, the freaking emperor would be a little more careful, but no. And it wasn’t just him — the vast majority of Napoleon’s marshals and other top lieutenants followed his example and met violent deaths.

This is one of the most lacking qualities in leaders today — it’s so bad that we don’t even realize what we’re missing. Obviously modern generals rarely put themselves in the line of fire or accept the same environmental hardships as their troops. But it isn’t just the military, how many corporate executives do you hear about staying late and suffering alongside their teams when crunch time hits? It does still happen, but it’s rare, and the most damning thing is that it’s usually because of some eccentricity in that particular individual. There’s no systemic impetus to commanders or managers sharing the suffering of their men, it just isn’t part of our model of what leadership is anymore. And yet we thirst for it.

Jane and John Psmith, “JOINT REVIEW: Napoleon the Great, by Andrew Roberts”, Mr. and Mrs. Psmith’s Bookshelf, 2023-01-21.

1. When not flinging them into the face of Prussian siege guns.

2. Okay, there are more than three. Some others include: deploying a cult of personality, bestowing all kinds of honors and awards on your men when they perform, and delivering them victory after victory. Of course, Napoleon did all of those things too.