Practical Engineering

Published Dec 5, 2023A friendly overview of thermal effects on railways.

Errata: At 9:00, the left column of calculations is incorrectly labeled “SI.” It should be imperial. Whoops!

Just as all materials have a mostly linear relationship between temperature change and length change, all materials also have a similar relationship between stress and change in length (often called strain). And this is part of the secret to continuous welded rail: restrained thermal expansion. You can overcome one with the other.

(more…)

March 11, 2024

Why Railroads Don’t Need Expansion Joints

QotD: The profound asshole-ishness of the “best of the best”

Ever met a pro athlete? How about a fighter pilot, or a trauma surgeon? I’ve met a fair amount of all of them, and unless they’re on their very best behavior they all tend to come off as raging assholes. And they get worse the higher up the success ladder they go — the pro athletes I’ve met were mostly in the minors, and though they were big-league assholes they were nothing compared to the few genuine “you see them every night on Sports Center” guys I met. Same way with fighter pilots — I never met an astronaut, but I had buddies at NASA back in the days who met lots, and they told me that even other fighter jocks consider astronauts to be world-class assholes …

The truth is, they’re not — or, at least, they’re no more so than the rest of the population. It’s just that they have jobs where total, utter, profoundly narcissistic self-confidence is a must. It’s what keeps them alive, in the pilots’ case at least, and it’s what keeps you alive if, God forbid, you should ever need the trauma surgeon. Same way with the sportsballers. I can say with 100% metaphysical certainty that there are better basketball players than Michael Jordan, better hitters than Mike Trout, better passers than Tom Brady, out there. There are undoubtedly lots of them, if by “better” you mean “possessed of more raw physical talent at the neuronal level”. What those guys don’t have, but Jordan, Brady, Trout et al do have, is the mental wherewithal to handle failure.

Everyone knows of someone like Billy Beane, the Moneyball guy. So good at football that he was recruited to replace John Elway (!!) at Stanford, but who chose to play baseball instead … and became one of the all-time busts. He had all the talent in the world, but his head wasn’t on straight. Not to put too fine a point on it, he doubted himself. He got to Double A (or wherever) and faced a pitcher who mystified him. Which made him think “Maybe I’m not as good as I think I am?” … and from that moment, he was toast as a professional athlete. Contrast this to the case of Mike Piazza, the consensus greatest offensive catcher of all time. A 27th round draftee, only picked up as a favor to a family friend, etc. Beane was a “better” athlete, but Piazza had a better head. Striking out didn’t make him doubt himself; it made him angry, and that’s why Piazza’s in the Hall of Fame and Beane is a legendary bust.

The problem though, for us normal folks, is that the affect in all cases is pretty much the same … and it’s really hard to turn off, which is why so many pro athletes (fighter jocks, surgeons, etc.) who are actually nice guys come off as assholes. It’s hard to turn off … but as it turns out, it’s pretty easy to turn ON, and that’s in effect what Game teaches.

Severian, “Mental Middlemen II: Sex and the City and Self-Confidence”, Rotten Chestnuts, 2021-05-06.

March 10, 2024

Viking longships and textiles

Virginia Postrel reposts an article she originally wrote for the New York Times in 2021, discussing the importance of textiles in history:

The Sea Stallion from Glendalough is the world’s largest reconstruction of a Viking Age longship. The original ship was built at Dublin ca. 1042. It was used as a warship in Irish waters until 1060, when it ended its days as a naval barricade to protect the harbour of Roskilde, Denmark. This image shows Sea Stallion arriving in Dublin on 14 August, 2007.

Photo by William Murphy via Wikimedia Commons.

Popular feminist retellings like the History Channel’s fictional saga Vikings emphasize the role of women as warriors and chieftains. But they barely hint at how crucial women’s work was to the ships that carried these warriors to distant shores.

One of the central characters in Vikings is an ingenious shipbuilder. But his ships apparently get their sails off the rack. The fabric is just there, like the textiles we take for granted in our 21st-century lives. The women who prepared the wool, spun it into thread, wove the fabric and sewed the sails have vanished.

In reality, from start to finish, it took longer to make a Viking sail than to build a Viking ship. So precious was a sail that one of the Icelandic sagas records how a hero wept when his was stolen. Simply spinning wool into enough thread to weave a single sail required more than a year’s work, the equivalent of about 385 eight-hour days. King Canute, who ruled a North Sea empire in the 11th century, had a fleet comprising about a million square meters of sailcloth. For the spinning alone, those sails represented the equivalent of 10,000 work years.

Ignoring textiles writes women’s work out of history. And as the British archaeologist and historian Mary Harlow has warned, it blinds scholars to some of the most important economic, political and organizational challenges facing premodern societies. Textiles are vital to both private and public life. They’re clothes and home furnishings, tents and bandages, sacks and sails. Textiles were among the earliest goods traded over long distances. The Roman Army consumed tons of cloth. To keep their soldiers clothed, Chinese emperors required textiles as taxes.

“Building a fleet required longterm planning as woven sails required large amounts of raw material and time to produce,” Dr. Harlow wrote in a 2016 article. “The raw materials needed to be bred, pastured, shorn or grown, harvested and processed before they reached the spinners. Textile production for both domestic and wider needs demanded time and planning.” Spinning and weaving the wool for a single toga, she calculates, would have taken a Roman matron 1,000 to 1,200 hours.

Picturing historical women as producers requires a change of attitude. Even today, after decades of feminist influence, we too often assume that making important things is a male domain. Women stereotypically decorate and consume. They engage with people. They don’t manufacture essential goods.

Yet from the Renaissance until the 19th century, European art represented the idea of “industry” not with smokestacks but with spinning women. Everyone understood that their never-ending labor was essential. It took at least 20 spinners to keep a single loom supplied. “The spinners never stand still for want of work; they always have it if they please; but weavers are sometimes idle for want of yarn,” the agronomist and travel writer Arthur Young, who toured northern England in 1768, wrote.

Shortly thereafter, the spinning machines of the Industrial Revolution liberated women from their spindles and distaffs, beginning the centuries-long process that raised even the world’s poorest people to living standards our ancestors could not have imagined. But that “great enrichment” had an unfortunate side effect. Textile abundance erased our memories of women’s historic contributions to one of humanity’s most important endeavors. It turned industry into entertainment. “In the West,” Dr. Harlow wrote, “the production of textiles has moved from being a fundamental, indeed essential, part of the industrial economy to a predominantly female craft activity.”

German Blunder Hands Allies a Rhine Crossing – WW2 – Week 289 – March 9, 1945

World War Two

Published 9 Mar 2024The Allies manage to take an intact bridge over the mighty Rhine at Remagen, a major piece of luck; the Germans launch a new offensive in Hungary, and the Allies end one in Italy. Over in Burma, Meiktila falls, sabotaging the entire Japanese supply system for the country, and on Iwo Jima the fight continues, bloodier than ever for both sides.

00:59 Recap

01:35 The Fall of Meiktila

03:46 The fight on Iwo Jima

05:27 Advances on the Western Front

07:44 The Rhine River

10:05 Remagen Bridge

16:20 Operation Encore

17:10 Rokossovsky and Zhukov attack

18:09 Operation Spring Awakening

21:57 Notes to end the week

23:42 Conclusion

(more…)

Why Germany Lost the Battle of Kursk, 1943

Real Time History

Published Nov 3, 2023In summer 1943, Germany and the Soviet Union fought the arguably biggest single battle in history with millions of men, thousands of tanks and artillery guns – the battle of Kursk. The German Army wanted to hit the Red Army so hard that they couldn’t go on the offensive again. And indeed, new research shows that the Soviets suffered shockingly high casualties, up to six times more men and equipment. But why then did the Germans lose this historic battle?

(more…)

QotD: Sustainability

I would argue that financial stability has everything to do with environmental sustainability (though I will admit that this comparison is a bit hard since environmentalists seem to bend over backwards to NOT define “sustainability” very precisely). In fact, I think that sustainability is baked right into the heart of capitalism.

The reason for this comes back to the magic of prices. Of all the amazing, wondrous things we celebrate in the world, prices may be the most overlooked. Just think of it: with no governing structure or top down ruling board, a single number encapsulates everything most everyone in the world knows about a particular product: both its utility and relative scarcity, both now and as anticipated in the future. It is a consensus derived voluntarily between millions of people who never meet with each other and likely never communicate with each other.

It is amazing to me that people who talk so much about their concern for scarcity tend to be the same folks who ignore prices and even eschew markets and capitalism. But in prices we have a number that gives us a single metric telling us the world’s consensus on the current and future scarcity of any commodity.

We do know that prices can miss some things. Perhaps most relevant today, they can fail to include the cost of emissions (ground, water, air) associated with that commodities extraction, refining and processing, and use. But compared to the effort of trying to create some alternate structure for managing product scarcity, this is a relatively simple problem to fix (simple technically, but not necessarily politically). Estimates of these pollution costs can be added as a tax (e.g. a carbon tax on fossil fuels to take into account climate effects of CO2 emissions) and prices will continue to work their magic but with these new factors added.

Warren Meyer, “Sustainability Is Baked Right Into the Heart of Capitalism”, Coyote Blog, 2019-10-10.

March 9, 2024

Salt – mundane, boring … and utterly essential

In the latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes looks at the importance of salt in history:

There was a product in the seventeenth century that was universally considered a necessity as important as grain and fuel. Controlling the source of this product was one of the first priorities for many a military campaign, and sometimes even a motivation for starting a war. Improvements to the preparation and uses of this product would have increased population size and would have had a general and noticeable impact on people’s living standards. And this product underwent dramatic changes in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, becoming an obsession for many inventors and industrialists, while seemingly not featuring in many estimates of historical economic output or growth at all.

The product is salt.

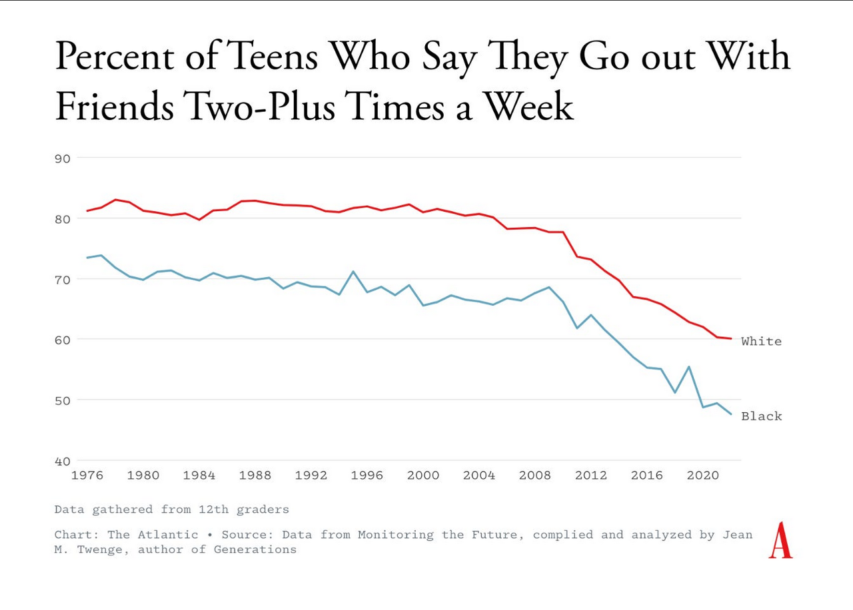

Making salt does not seem, at first glance, all that interesting as an industry. Even ninety years ago, when salt was proportionately a much larger industry in terms of employment, consumption, and economic output, the author of a book on the history salt-making noted how a friend had advised keeping the word salt out of the title, “for people won’t believe it can ever have been important”.1 The bestselling Salt: A World History by Mark Kurlansky, published over twenty years ago, actively leaned into the idea that salt was boring, becoming so popular because it created such a surprisingly compelling narrative around an article that most people consider commonplace. (Kurlansky, it turns out, is behind essentially all of those one-word titles on the seemingly prosaic: cod, milk, paper, and even oysters).

But salt used to be important in a way that’s almost impossible to fully appreciate today.

Try to consider what life was like just a few hundred years ago, when food and drink alone accounted for 75-85% of the typical household’s spending — compared to just 10-15%, in much of the developed world today, and under 50% in all but a handful of even the very poorest countries. Anything that improved food and drink, even a little bit, was thus a very big deal. This might be said for all sorts of things — sugar, spices, herbs, new cooking methods — but salt was more like a general-purpose technology: something that enhances the natural flavours of all and any foods. Using salt, and using it well, is what makes all the difference to cooking, whether that’s judging the perfect amount for pasta water, or remembering to massage it into the turkey the night before Christmas. As chef Samin Nosrat puts it, “salt has a greater impact on flavour than any other ingredient. Learn to use it well, and food will taste good”. Or to quote the anonymous 1612 author of A Theological and Philosophical Treatise of the Nature and Goodness of Salt, salt is that which “gives all things their own true taste and perfect relish”. Salt is not just salty, like sugar is sweet or lemon is sour. Salt is the universal flavour enhancer, or as our 1612 author put it, “the seasoner of all things”.

Making food taste better was thus an especially big deal for people’s living standards, but I’ve never seen any attempt to chart salt’s historical effects on them. To put it in unsentimental economic terms, better access to salt effectively increased the productivity of agriculture — adding salt improved the eventual value of farmers’ and fishers’ produce — at a time when agriculture made up the vast majority of economic activity and employment. Before 1600, agriculture alone employed about two thirds of the English workforce, not to mention the millers, butchers, bakers, brewers and assorted others who transformed seeds into sustenance. Any improvements to the treatment or processing of food and drink would have been hugely significant — something difficult to fathom when agriculture accounts for barely 1% of economic activity in most developed economies today. (Where are all the innovative bakers in our history books?! They existed, but have been largely forgotten.)

And so far we’ve only mentioned salt’s direct effects on the tongue. It also increased the efficiency of agriculture by making food last longer. Properly salted flesh and fish could last for many months, sometimes even years. Salting reduced food waste — again consider just how much bigger a deal this used to be — and extended the range at which food could be transported, providing a whole host of other advantages. Salted provisions allowed sailors to cross oceans, cities to outlast sieges, and armies to go on longer campaigns. Salt’s preservative properties bordered on the necromantic: “it delivers dead bodies from corruption, and as a second soul enters into them and preserves them … from putrefaction, as the soul did when they were alive”.2

Because of salt’s preservative properties, many believed that salt had a crucial connection with life itself. The fluids associated with life — blood, sweat and tears — are all salty. And nowhere seemed to be more teeming with life as the open ocean. At a time when many believed in the spontaneous generation of many animals from inanimate matter, like mice from wheat or maggots from meat, this seemed a more convincing point. No house was said to generate as many rats as a ship passing over the salty sea, while no ship was said to have more rats than one whose cargo was salt.3 Salt seemed to have a kind of multiplying effect on life: something that could be applied not only to seasoning and preserving food, but to growing it.

Livestock, for example, were often fed salt: in Poland, thanks to the Wieliczka salt mines, great stones of salt lay all through the streets of Krakow and the surrounding villages so that “the cattle, passing to and fro, lick of those salt-stones”.4 Cheshire in north-west England, with salt springs at Nantwich, Middlewich and Northwich, has been known for at least half a millennium for its cheese: salt was an essential dietary supplement for the milch cows, also making it (less famously) one of the major production centres for England’s butter, too. In 1790s Bengal, where the East India Company monopolised salt and thereby suppressed its supply, one of the company’s own officials commented on the major effect this had on the region’s agricultural output: “I know nothing in which the rural economy of this country appears more defective than in the care and breed of cattle destined for tillage. Were the people able to give them a proper quantity of salt, they would … probably acquire greater strength and a larger size.”5 And to anyone keeping pigeons, great lumps of baked salt were placed in dovecotes to attract them and keep them coming back, while the dung of salt-eating pigeons, chickens, and other kept birds were considered excellent fertilisers.6

1. Edward Hughes, Studies in Administration and Finance 1558 – 1825, with Special Reference to the History of Salt Taxation in England (Manchester University Press, 1934), p.2

2. Anon., Theological and philosophical treatise of the nature and goodness of salt (1612), p.12

3. Blaise de Vigenère (trans. Edward Stephens), A Discovrse of Fire and Salt, discovering many secret mysteries, as well philosophical, as theological (1649), p.161

4. “A relation, concerning the Sal-Gemme-Mines in Poland”, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London 5, 61 (July 1670), p.2001

5. Quoted in H. R. C. Wright, “Reforms in the Bengal Salt Monopoly, 1786-95”, Studies in Romanticism 1, no. 3 (1962), p.151

6. Gervase Markam, Markhams farwell to husbandry or, The inriching of all sorts of barren and sterill grounds in our kingdome (1620), p.22

The Jewish Avengers Who Hunted Nazi Murderers

World War Two

Published Mar 8, 2024In March 1945, the first Jewish unit in the Allied forces reaches the frontline. Before fighting the Nazis, the men spent years battling against the policies of the British government. After the war, they will take vengeance on the perpetrators of the Holocaust and join the Zionist movement in building and fighting for Israel.

(more…)

1871 Spencer Rifle Conversion

Forgotten Weapons

Published Nov 12, 2014The Spencer repeating rifle was a major leap forward in infantry firepower, and more than one hundred thousand of them were purchased by the US military during the Civil War. The Spencer offered a 7-round magazine of rimfire .56 caliber cartridges in an era when the single-shot muzzle-loading rifle was still predominant. This particular Spencer is a long rifle which was one of roughly 1100 rebuilt from damaged carbines in 1871 at Springfield Arsenal.

(more…)

QotD: Reading for snobs

I would like, for the sake of hipness, to be able to claim that I am reading some obscure French novelist of the inter-war period, in the original French. Unfortunately, the only thing I can read in the original French is no-smoking signs, and I hate most French novels written after 1890. Instead, I’m reaquainting myself with the poetry of Edna St. Vincent Millay and Dorothy Parker, the patron saints of light verse. When I was in college, I thought I wanted to be Dorothy Parker, until I realised that no matter how hard I tried I was never going to be talented, Jewish, or short, and that dying alone only sounds romantic so long as you continue to believe yourself to be immortal.

Megan McArdle, writing as “Jane Galt”, Asymmetrical Information, 2004-12.

March 8, 2024

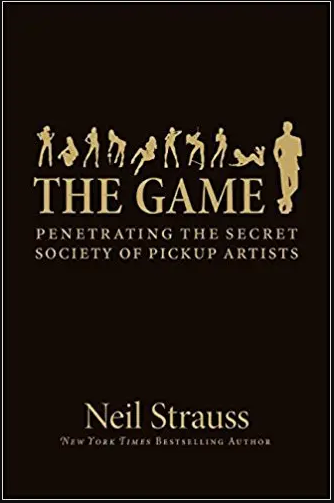

A fresh look at the PUA “bible”

In UnHerd, Kat Rosenfield considers the original pick-up artist bible, The Game by Neil Strauss, in light of more than a decade of changes in how moderns approach relationships with the opposite sex:

A decade letter, I’m struck by the astonishing prescriptiveness of this line: the notion that any sexual encounter preceded by flirtation, negotiation, or indeed any assessment of a suitor’s desirability should be understood as “less-than-ideal” — and that any man who seeks to make himself desirable to an as-yet-uncertain woman is doing something inherently sleazy. Granted, the anti-Game backlash began in the form of reasonable scrutiny of controversial seduction techniques like “negging” (a slightly backhanded compliment deployed for the sake of flirtation).

But since then it has morphed into something much stranger: the idea that anything a man does to impress a woman, from basic grooming to speaking in complete sentences, should be viewed with suspicion. Behind this is the same low-trust mindset that leads women to treat every date as a hunt for the red flags that reveal her suitor as a secret monster. If he compliments you? That’s lovebombing, which means he’s an abuser. If he doesn’t compliment you, that’s withholding, which also means he’s an abuser. Other alleged “red flags” include oversharing, undersharing, paying for the date, not paying for the date, being too eager, being five minutes late, and drinking water — or worse, drinking water through a straw.

Today, the turn against pick-up artistry can be understood at least in part as a reaction against some of its more prominent contemporary practitioners, including men such as Andrew Tate, who makes Mystery look like a catch by comparison. But it is also no doubt an outgrowth of a culture in which male sexuality has effectively been characterised as inherently predatory, while female sexuality is seen as virtually non-existent. The question that seduction manuals once aimed to answer — “how do I, a shy young man, successfully and confidently approach women?” — is now, in itself, a red flag, one likely to provoke anything from squawking indignation to abject horror to bystanders wondering if they ought to call the police. That you are even thinking of approaching women just goes to show what a troglodyte you really are. What do women want? The contemporary answer appears to be: to be left alone, forever, until they die — or to meet someone in a safe and sanitised way, via dating app … although even that option is increasingly positioned as inherently dangerous.

Meanwhile, I was surprised upon revisiting The Game to realise that the strategies contained within the book are not just useful but mostly in keeping with more traditional dating and courtship advice, from “peacocking” (wearing something eye-catching or unusual that can act as a conversation starter), to passing “shit tests” (responding with humour and confidence when a woman teases you). Even the much-derided negging wasn’t originally designed with the goal of insulting or belittling women, but rather to teach men how to talk to them without fawning and drooling all over the place. In the end, the message of The Game is more or less identical to the one in popular women’s dating guides, like The Rules or He’s Just Not That Into You: that confidence is sexy, and naked desperation is a turnoff.

And while this may just be a function of one too many viewings of the BBC’s Pride & Prejudice (featuring Mr Darcy, a man in possession of £50,000 a year and an absolutely legendary negging game), I wonder if the aim of seduction guides is, paradoxically, to restore our confidence in the tension, the mystery, and the playfulness of courtship in the age of the casual hookup. Even as we rightly rejoice in the fact that society no longer stigmatises women for desiring and pursuing sex, there is surely still something to be said for subtlety — and just because we aren’t consigned to the role of the passive damsel, dropping a handkerchief on the ground in the hope that the right man will pick it up, that doesn’t mean every woman wants to be horny on main. It’s not just that announcing your desire through a megaphone can seem uncouth; it’s also a lot less exciting than the dance of lingering glances, double entendres, and simmering chemistry that characterises a mutually-desired seduction in the making. Certain people might deride this brand of sexual encounter as “less-than-ideal” for its political incorrectness, but it’s wildly popular — in novels, in films, and in the fantasies of individual women — for a reason.

Meanwhile, the contemporary dating landscape is one in which the sheer fun of dating, courtship, and, yes, falling into bed together has been largely back-burnered in favour of something at once formal and immensely self-serious. In a world of handwringing over sexual consent — in which a man just talking to a woman at a coffeeshop can trigger an emergency response protocol — the stakes of sex itself come to seem unimaginably high, a breakneck gamble where one wrong move will result in a lifetime of trauma (or, if you’re a guy, a lifetime on a list of shitty men). Add to this the proliferation of dating apps, which makes the entire romantic enterprise feel more like a job search than a playground, and the whole thing begins to seem not just fraught but inherently adversarial — a negotiation between two parties whose interests are completely at odds, who cannot trust each other, and where there’s a very real risk of terrible and irreparable harm.

How the elites used bait-and-switch tactics to sell the idea of “15-minute cities”

In The Critic, Alex Klaushofer outlines how the Oxfordshire County Council introduced the 15-minute city nonsense for Oxford:

This time last year I watched with bemusement as a strange new trend emerged in my native Britain. Councils were introducing restrictions on citizens moving about by car. Living in Portugal had given me an observer’s detachment and I struggled to reconcile what I was seeing with the country I knew.

Oxford — my alma mater and the city where I regularly used to lose my bicycle — was at the heart of it. In November 2022, Oxfordshire County Council approved an experimental traffic scheme in a city notorious for congestion. Traffic filters would divide the city into zones, with those wishing to drive between them obliged to apply for permits.

Residents would be allocated passes for up to 100 journeys a year and those living outside the permit area 25. The zones would be monitored by automatic number plate recognition cameras and any journeys taken without permits would result in fines.

Duncan Enright, the councillor with responsibility for travel strategy told the Sunday Times the scheme would turn Oxford into a 15-minute city: “It is about making sure you have the community centre which has all of those essential needs, the bottle of milk, pharmacy, GP, schools which you need to have a 15-minute neighbourhood”.

The explanation didn’t make sense. The council was presenting a scheme centred around restrictions on the movement of vehicles on the basis of something quite different: the desirability of local facilities. It was part of a plan for a “net zero transport system” which included a commitment to “20-minute neighbourhoods: well-connected and compact areas around the city of Oxford where everything people need for their daily lives can be found within a 20-minute walk”.

Yet the Central Oxfordshire Travel Plan made no provision for new services or even assessing existing amenities. Instead, flourishing neighbourhoods were to be achieved by the simple expedient of making it difficult for people to drive across the city. Residents, visitors and businesses would make only “essential” — the word was highlighted in bold — car journeys. And while they would still be able to enter and exit Oxford via the ring road, “a package of vehicle movement restrictions” would “encourage” people to live locally.

Traffic management or social engineering? The council’s plan looked like a case of bait-and-switch: citizens were being enticed to accept one thing on the promise of another. And, judging by the increasing revenues other councils were collecting through cameras, the scheme would be a nice earner.

The vast amount of media coverage on 15-minute cities fuelled the fundamental confusion at the heart of the Oxford scheme. Instead of examining its implications, journalists characterised those questioning the proposals as “conspiracy theorists” who were wilfully refusing leafy roads and local markets. “What are 15-minute cities and why are anti-vaxxers so angry about them?” ran a headline in The Times.

The Guardian published a piece titled “In praise of the 15-minute city” which mocked “libertarian fanatics and the bedroom commentators of TikTok”, claiming they belonged to an “anti-vaccine, pro-Brexit, climate-denying, 15-minute-phobe, Great Reset axis”. What had happened to the newspaper I’d read for decades and on occasion written for, with its understanding of the effects of policies on ordinary people?

The public debate around the Oxford experiment completely bypassed the obvious practicalities. What about a typical family, juggling work with school runs and after-school activities? Having to drive out of the city and around its periphery for each trip could make their lives impossible. How would those whose work wasn’t accessible by public transport manage on the two permitted journeys a week?

Know Your Ship #20 – Flower Class Corvettes

iChaseGaming

Published Oct 27, 2014Episode 20 of Know Your Ship! In this educational video I cover the Flower class corvettes. These corvettes used by the Royal Canadian Navy and the Royal Navy to great effect during the Battle of the Atlantic. The Flower class were built quickly and cheaply in order to provide as many ships for convoy duty and anti-submarine operations as possible. The Royal Canadian Navy in particular achieved significant success and became experts in anti-submarine operations. Sadly, these ships and their crews are mostly forgotten with the passage of time as attention is mostly given to the surviving capital ships. It is my hope that this educational video will help people to understand and know these important ships that helped safeguard the convoys during World War 2. The only remaining ship of this class is HMCS Sackville which you will see later in this episode.

(more…)