Last time, we introduced the factors that created the trench stalemate in the First World War and we also laid out why the popular “easy answer” of simply going on the defensive and letting the enemy attack themselves to death was not only not a viable strategy in theory but in fact a strategy which had been tried and had, in the event, failed. But in discussing the problem the trench stalemate created on the Western Front, I made a larger claim: not merely that the problem wasn’t solved but that it was unsolvable, at least within the constraints of the time. This week we’re going to pick up that analysis to begin looking at other options which were candidates for breaking the trench stalemate, from new technologies and machines to new doctrines and tactics. Because it turns out that quite to the contrary of the (sometimes well-earned) dismal reputation of WWI generals as being incurious and uncreative, a great many possible solutions to the trench stalemate were tried. Let’s see how they fared.

Before that, it is worth recapping the core problem of the trench stalemate laid out last time. While the popular conception was that the main problem was machine-gun fire making trench assaults over open ground simply impossible, the actual dynamic was more complex. In particular, it was possible to create the conditions for a successful assault on enemy forward positions – often with a neutral or favorable casualty ratio – through the use of heavy artillery barrages. The trap this created, however, was that the barrages themselves tore up the terrain and infrastructure the army would need to bring up reinforcements to secure, expand and then exploit any initial success. Defenders responded to artillery with defense-in-depth, meaning that while a well-planned assault, preceded by a barrage, might overrun the forward positions, the main battle position was already placed further back and well-prepared to retake the lost ground in counter-attacks. It was simply impossible for the attacker to bring fresh troops (and move up his artillery) over the shattered, broken ground faster than the defender could do the same over intact railroad networks. The more artillery the attacker used to get the advantage in that first attack, the worse the ground his reserves had to move over became as a result of the shelling, but one couldn’t dispense with the barrage because without it, taking that first line was impossible and so the trap was sprung.

(I should note I am using “railroad networks” as a catch-all for a lot of different kinds of communications and logistics networks. The key technologies here are railroads, regular roads (which might speed along either leg infantry, horse-mobile troops and logistics, or trucks), and telegraph lines. That last element is important: the telegraph enabled instant, secure communications in war, an extremely valuable advantage, but required actual physical wires to work. Speed of communication was essential in order for an attack to be supported, so that command could know where reserves were needed or where artillery needed to go. Radio was also an option at this point, but it was very much a new technology and importantly not secure. Transmissions could be encoded (but often weren’t) and radios were expensive, finicky high technology. Telegraphs were older and more reliable technology, but of course after a barrage the attacker would need to be stringing new wire along behind them connecting back to their own telegraph systems in order to keep communications up. A counter-attack, supported by its own barrage, was bound to cut these lines strung over no man’s land, while of course the defender’s lines in their rear remained intact.)

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: No Man’s Land, Part II: Breaking the Stalemate”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2021-09-24.

August 30, 2024

QotD: The stalemate in the trenches, 1914-1918

August 29, 2024

Britain’s empire after WWII

From my readings about the behind-the-scenes negotiations among the western allies even before the United States formally entered the war in late 1941, I’ve always felt that the personal relationship between Winston Churchill and Franklin Delano Roosevelt was at least as important as the formal public proclamations and direct actions of the allies. It’s my belief that Churchill and FDR had a “wink and a nod” agreement for the US to continue supporting the British economy after the end of the war in Europe, probably in exchange for a gradual retreat from formal Imperial control over at least some of the remaining British colonies. This would have made Britain’s immediate postwar experience far less grim economically and politically and allowed the British economy to gracefully switch from full wartime production to fulfilling peacetime business and consumer needs.

Church services on HMS Prince of Wales, in Placentia Bay, Newfoundland, during the Atlantic Charter Conference. President Franklin D. Roosevelt (left) and Prime Minister Winston Churchill are seated in the foreground. Standing directly behind them are Admiral Ernest J. King, USN; General George C. Marshall, U.S. Army; General Sir John Dill, British Army; Admiral Harold R. Stark, USN; and Admiral Sir Dudley Pound, RN. At far left is Harry Hopkins, talking with W. Averell Harriman.

US Naval Historical Center Photograph #: NH 67209 via Wikimedia Commons.

Of course, with Roosevelt dead (and Truman certainly not “read-in” on any unwritten promises to the British) and Churchill out of office (which was as much of a shock to the Americans as it was to Churchill himself), whatever they may have hoped to do was now so much wishful thinking. Britain had to not just continue wartime rationing after VE and VJ Day, but to actually make it more stringent for nearly a decade just to avoid national bankruptcy … and the withdrawal from imperial outposts had to be done as quickly and as cheaply as possible. This often meant corners were cut, cheeses were pared, and shortcuts availed of, so that the experiences of the former colonies were more fraught with civil disturbances and commercial disruptions than they should have been.

All of this is a very long-winded way to introduce Joshua Treviño’s post at Armas which considers how an American imperial decline may or may not mirror the postwar British experience of de-imperialization:

We can guess that American decline under the present regime will look much like Britain’s. The British case is taken as so normative — of course a nation will decline after its empire is gone — that the normativity goes unquestioned. But this is the worst sort of history, determinative in retrospect, as if the loss of imperium (or more properly, the loss of imperial fiscal stability) set in motion dominoes that fell unstoppably until the latest squalid episode of Keir Starmer’s thought police. That isn’t how human events work, however: all things are contingent. Britain was, in the eyes of several European powers, reduced to a mid-tier power after the catastrophic loss of America at the opening of the 1780s — and a generation later it was the indispensable nation versus French hegemony. There was not any particular reason a comparable recovery ought not have happened in the generation after 1945, even with the loss the of the empire, and even with the great postwar crisis of the pound sterling. This was in fact the high-Tory view as set forth by Enoch Powell, who evolved toward a belief that the empire was a burden on Britain, which could ascend to its destiny and fulfillment by means of the British themselves.

That this did not happen is plausibly much the fault of the Americans, who did two major things — one of them unwittingly — to forestall this sort of recovery. The first act, undertaken with deliberation, was the credible American threat to destroy the United Kingdom’s finances and economy in the 1956 Suez crisis: in no way the act of an ally, and one whose psychological effects upon Britain’s governing elites were as significant as the hard-power effects upon Britain itself. (Though I am not a particular fan of De Gaulle, for reasons that may be discussed here later, he was unquestionably a better steward of the nation than his U.K. counterparts in his conclusion — admittedly coalescing a decade earlier — that a European state could be a major power, or it could be a junior partner to the United States, but not both.) The British regime’s reaction to the episode — to draw so close to the Americans as to abandon the nation’s strategic independence — thereby contributed powerfully to Britain’s subsequent diminishment. That diminishment was not simply in the realm of hard power: it was accompanied by a profound social and governmental malaise that has fluctuated across the decades but has yet to lift. Philip Larkin’s 1969 Homage to a Government captures it well:

Next year we are to bring all the soldiers home

For lack of money, and it is all right.

Places they guarded, or kept orderly,

Must guard themselves, and keep themselves orderly

We want the money for ourselves at home

Instead of working. And this is all right.It’s hard to say who wanted it to happen,

But now it’s been decided nobody minds.

The places are a long way off, not here,

Which is all right, and from what we hear

The soldiers there only made trouble happen.

Next year we shall be easier in our minds.Next year we shall be living in a country

That brought its soldiers home for lack of money.

The statues will be standing in the same

Tree-muffled squares, and look nearly the same.

Our children will not know it’s a different country.

All we can hope to leave them now is money.The superficial read of Larkin here is that he laments deriving purpose from other things closer to home. There is a baseness in the imperialist’s love of mission, and he misses the sublime in, say, the National Health Service. It is a dumb atavism: if the “tree-muffled squares … look nearly the same”, then why does it matter that “the soldiers [are] home”? This interpretation is wrong. What Larkin laments is the loss of the common and noble purpose in the civic partnership that makes the nation, as defined at the outset of Aristotle’s Politics — without which the nation fails to cohere, even if its regime persists. Despite the strenuous efforts of the left and progressivism across the past century, that virtuous end to which the nation has been directed has never been supplanted in its old forms — religion, glory, strength, creation — by any new ones of social programs or millennialist materialism. When Clement Attlee wrote in his 1920 The Social Worker that the Protestant Reformation was to blame for the moral degradation of charity, his solution was not the obvious one (which is to say, the restoration of Catholic England or at least its mores), but to interpose government where religion and its purposes used to be. His 1945 general-election invocation of building “Jerusalem” in England, directly quoting William Blake, logically followed.

But that is not how Jerusalem is built. It remains unbuilt, and the civic effects of the American fixation and what it facilitates redound across time. Nick Cohen accuses the modern British right of Americanizing itself, and that is largely accurate, but contra his indictment, the British left does the same in different ways. What the Americans did in 1956 was not a singular event — rather it was a punctuation on a process that had been unfolding in stages for the preceding forty years or so — but their objects got a vote too. That vote was to submit, a preference shared across right and left alike. That no American regime ever had Britain’s interest fully at heart (a truth with ample reminders, not just at Suez, but in Northern Ireland, in the Falklands, in Grenada, in Iraq, and in Afghanistan) did not alter this course, thereby making a triumph of theory unmoored from fact.

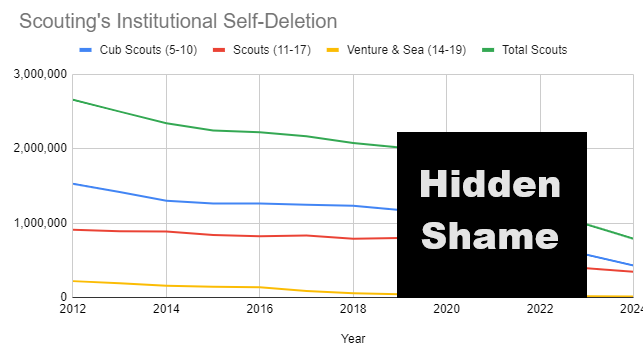

How activists used lawfare to force the Boy Scouts to go woke (and then go broke)

A guest post from Cole Noble at Postcards From Barsoom discusses how progressive organizations and political activists have managed an immense take-over of the great outdoors, not least of which were the legal and political efforts to force the Boy Scouts of America to accept gay scouts and scout masters:

[…] This entertainment ecosystem, increasingly infested with culture warriors, also started chipping away at the longstanding prestige of organizations like the BSA [Boy Scouts of America]. Depicting someone as a scout became a kind of character development shorthand, signalling them as uncool.

The targeting wasn’t incidental; the existence of the pre-centennial BSA was a serious problem for the ruling class. Their organization’s commitment to values-based conservation served as living proof that going along with society’s adoption of critical theory was completely optional. If the BSA was free to refuse the push, others might start getting ideas.

Lawfare was inevitable.

In 2000, the United States Supreme Court heard Boy Scouts of America v. Dale. In one corner you had James Dale, an avowed gay rights activist, co-president of the Rutgers University Lesbian/Gay Alliance, and outspoken advocate for gay teens having gay role models. In the other, you had the BSA, who didn’t want someone like Dale around its young, impressionable members.

The BSA won, but there was blood in the water. Culture warriors circled back around, this time employing social pressure. They tried to make their demand sound as reasonable as possible: drop the policy against openly gay members. Just one teeny tiny rule. What’s the point anyway? It’s outdated. No real sense keeping it, right?

Smart members of the program clocked this Trojan Horse from miles away. Alas, the organization’s leadership did not. Possessing both the physique and fortitude of rice pudding, they caved, capitulated, and acquiesced some more — agreeing to an ever-escalating series of demands that hollowed out the once-proud group into an empty vessel for The Current Thing(TM).

The Boy Scouts of America is now all-inclusive! Not just to gay scouts and leaders, but girls too. In a show of solidarity with Black Lives Matter after the riots of 2020, a mandatory DEI merit badge has replaced camping as a requirement to attain the once coveted rank of Eagle Scout.

Let’s not forget the Scout Masters now left to deal with teens using the program’s overnight trips as cover for hookups.

Oh, and they went bankrupt.

The organization agreed to a 2.5 billion dollar settlement over tens of thousands of sex abuse cases perpetuated by adult men, against underage boys.

Rather than bolster ranks, adopting DEI cost the organization more than 1 million members.

The BSA – sorry, Scouting America1 – didn’t publish annual membership reports from 2020 to 2022, I imagine out of embarrassment. During this time, the Mormons, who used Scouting as a youth program for its boys, took their 400,000 members, and their money, and left.

[…]

Scouting was one of, if not the last bastion of quasi-unstructured outdoor activities. While the death of free-range childhood seems to be commonly understood, there is some debate about the precise cause.

Whatever your opinion on the matter, regime journalists shoulder enormous responsibility for eroding societal trust and inspiring mass paranoia through sensational reporting. Former latchkey kids became hysterical helicopter parents, petrified of letting their children out of sight.

Playing outside became a heavily supervised affair, usually relegated to fenced-in backyards with locking gates.

Kids have been robbed of the experiences that could lead them to develop an organic appreciation for outdoor recreation, and groomed into a hypersexualized version of early adulthood. All the while, the institutions which once taught conservation and virtue now serve as apparatuses of critical theory.

1. They changed their name in May of 2024, after 114 of being the Boy Scouts. Since they’re no long the Boy Scouts, this is at least honest.

Cole’s own Substack is Quandary Magazine, which you should check out if you’re generally interested in the great outdoors.

Pavel Durov’s arrest isn’t for a clear crime, it’s for allowing everyone access to encrypted communications services

J.D. Tuccille explains the real reason the French government arrested Pavel Durov, the CEO of Telegram:

It’s appropriate that, days after the French government arrested Pavel Durov, CEO of the encrypted messaging app Telegram, for failing to monitor and restrict communications as demanded by officials in Paris, Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg confirmed that his company, which owns Facebook, was subjected to censorship pressures by U.S. officials. Durov’s arrest, then, stands as less of a one-off than as part of a concerted effort by governments, including those of nominally free countries, to control speech.

“Telegram chief executive Pavel Durov is expected to appear in court Sunday after being arrested by French police at an airport near Paris for alleged offences related to his popular messaging app,” reported France24.

A separate story noted claims by Paris prosecutors that he was detained for “running an online platform that allows illicit transactions, child pornography, drug trafficking and fraud, as well as the refusal to communicate information to authorities, money laundering and providing cryptographic services to criminals”.

Freedom for Everybody or for Nobody

Durov’s alleged crime is offering encrypted communications services to everybody, including those who engage in illegality or just anger the powers that be. But secure communications are a feature, not a bug, for most people who live in a world in which “global freedom declined for the 18th consecutive year in 2023”, according to Freedom House. Fighting authoritarian regimes requires means of exchanging information that are resistant to penetration by various repressive police agencies.

“Telegram, and other encrypted messaging services, are crucial for those intending to organise protests in countries where there is a severe crackdown on free speech. Myanmar, Belarus and Hong Kong have all seen people relying on the services,” Index on Censorship noted in 2021.

And if bad people occasionally use encrypted apps such as Telegram, they use phones and postal services, too. The qualities that make communications systems useful to those battling authoritarianism are also helpful to those with less benign intentions. There’s no way to offer security to one group without offering it to everybody.

As I commented on a post on MeWe the other day, “Somehow the governments of the west are engaged in a competition to see who can be the most repressive. Canada and New Zealand had the early lead, but Australia, Britain, Germany, and France have all recently moved ahead in the standings. I’m not sure what the prizes might be, but I strongly suspect “a bloody revolution” is one of them (if not all of them).”

How to Make a Ladle | Episode 1

Paul Sellers

Published Apr 26, 2024It may not be a large project, but creating a ladle from fully kiln-dried hardwoods like sycamore and maple differs from green, uncured wood. Tougher to carve yes, but there is no shrinkage and no risk of cracking through drying. It is a wonderful project for learning to work with multi-directional grain and to also use gouges and such.

This is a great beginner guide for those starting with gouge work.

——————–

(more…)

QotD: The Price of Speed

Recently, over lunch, Mrs. Muros regaled me with tales of authors who treat their readers to several new novels a year. As she waxed rhapsodic on the subject of the people who put the “p” in “prolific”, I scribbled notes on a credit card receipt. “Why is it”, I wrote, “that these ink-strained Atalantas can fill several pages with reasonably readable prose in the time it takes me to assemble a simple Substack post?”

The answer, I mused, might have something to do with sex. All of the authors mentioned by My Yankee Sweetheart, after all, were fully paid-up members of the distaff half of humanity. Could it be that my words fail to flow like summertime honey because my brain has been pickled in androgens? Or, to be somewhat less of a bio-Calvinist, could it be that my refusal to engage in the formal study of literature — a policy which owed much to my belief that the subject was “for girls” — left me bereft of some of the most useful tools of the writer’s trade?

Later that day, as I ransacked back issues of obscure journals in the hope of finding an uncooperative fact, a warm yellow bulb of incandescent understanding appeared above my head. ‘Twas not the writing that slowed me down, I realized, but the research. Indeed, were it not for the pesky puzzle piece I was trying to find, my article would have been done and dusted well before The Love of My Life and I sat down to our midday meal.

Before it faded, my wee epiphany bore two sprogs. The elder of these reminded me that, like other forms of mass production, the prodigious productivity of the quill-drivers in question owed much to the avoidance of novelty. That is, they were able to write so much because, in effect, they made repeated use of familiar formulae, tried-and-true tropes, and recurring turns-of-phrase. The younger of my mind-sparks added that, in addition to taking up time that an writer might otherwise spend at the keyboard, the discovery of a new fact will often lead to a quest for fresh forms of expression.

So, to quote the immortal words of David Crowther, you pays your money and you takes your choice. You can write quickly, or you can say something new, but you can’t do both.

Bruce Ivar Gudmundsson, “The Price of Speed”, Extra Muros, 2024-05-21.

August 28, 2024

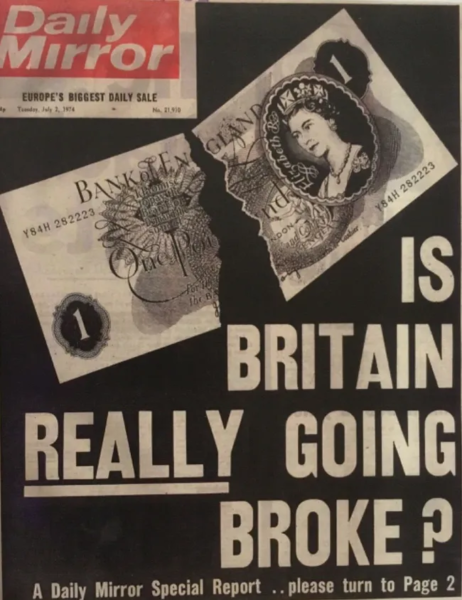

1974 – Britain’s nadir

In the second part of Ed West‘s appreciation of Dominic Sandbrook’s Seasons in the Sun, Britain was described as “sliding, sinking, shabby, dirty, lazy, inefficient, dangerous, in its death throes, worn out, clapped out, occasionally lashing out” by Margaret Drabble in her 1977 novel The Ice Age, and it certainly seems to fit the bill quite well:

The Times reported in October of that year that London’s West End was in a “sorry state”, with parts of Shaftesbury Avenue and Charing Cross Road “in the sort of condition that, in Birmingham or Manchester, would qualify them for wholesale slum clearance”.

Journalist Clive Irving wrote that London had become “a semi-derelict slum”, a city blighted by “tacky porno shops, skin movies, pinball arcades, and toxic hamburger joints” while “behind neon facades the buildings are flaking and unkempt”.

The capital had lost a million and a half people since its peak in 1939, and would continue its decline for another decade. Whitehall Mandarin Ronald McIntosh declared that “London is evidently losing population quite heavily [and] services are steadily deteriorating, and nobody seems to have the least idea of how to deal with it”.

The country as a whole was haemorrhaging people, and in 1975 its population fell for the first time since records began. In the spring of 1974 applications for emigration to Canada went up 65 per cent, while New Zealand even felt compelled to put restrictions on people fleeing the old country.

Doctors in particular were leaving in droves, and recruitment agency Robert Lee International estimated that the number of professionals wanting to move abroad rose by 35% in just six months, from January and July 1975. Interest was keenest among engineers, accountants, scientists and teachers.

Many high earners were fleeing excessive tax rates, so punitive that even the Bond producer Albert R Broccoli left to make the iconic British movies elsewhere, and Moonraker would be filmed in France.

Gone were the days of the Swinging Sixties; instead, the London of George Smiley was “the city of the Sex Pistols and The Sweeney, not the Beatles and The Avengers; a city of tramps and hooligans, hustlers and muggers, the downtrodden and the disappointed, haunted by the deadly figure of the IRA bomber”.

Britain’s second city was in an even worse state. During Wilson’s first term Birmingham had been hailed as “the most go-ahead city in Europe”. Now the Times admitted it looked like a “large and chaotic building site”.

Travel writer Jonathan Raban described Southampton’s Millbrook estate as “a vast, cheap storage unit for nearly 20,000 people”. The country’s increasing problem with crime, hooliganism, graffiti and drug addiction meant that residents wouldn’t even hang their clothes in communal areas, for fear of theft.

The great architectural feats of the post-war era were beginning to look like a miserable failure, and none more so than the utopian social housing schemes, which had often entailed destroying closely-knit and organic communities in overcrowded and run-down – but rescuable – terraced housing.

Christopher Brooker visited Keeling House in Bethnal Green and found “its concrete cracked and discolouring, the metal reinforcement rusting through the surface, every available inch covered with graffiti”. Here was the story of modern Britain, “the bright, anticipated dream followed by a seedy, nightmarish reality”.

The National Theatre’s Peter Hall visited the New York Juilliard School and upon return home “found it depressing to compare it with our own already run-down, ill-maintained South Bank building”.

“The English apparently no longer care enough about material surroundings,” he wrote: “They even seem to take a positive pleasure in defiling them.”

The Korean War Week 010 – MacArthur and the Incheon Meeting – August 27, 1950

The Korean War by Indy Neidell

Published 27 Aug 2024Douglas MacArthur has a plan for an amphibious invasion of Incheon, and he thinks it will turn the tide of the war. This week comes his heavy pitch to be allowed to do it to the powers-that-be among American command. The war in the field continues as the UN forces win the Battle of the Bowling Alley, but an air force attack accidentally hits targets over the border in China. Mao Zedong is furious. Also, MacArthur gets flak this week from the President for outspokenly advocating actions counter to US official policy with regard to China, so the Chinese situation grows ever more tense.

Chapters

01:28 Battle of the Bowling Alley

04:14 U.N. Air Power

06:46 Supply Issues

09:05 The British are coming

10:55 Incheon Plans

14:52 The Incheon Meeting

17:06 MacArthur and the VFW

20:25 KPA Plans for Next Week

21:24 Summary

(more…)

H.R. McMaster dishes on Trump’s first term in office

In Reason, Liz Wolfe covers some of the head-scratchers former National Security Advisor H.R. McMaster revealed about working for Donald Trump:

Donald Trump addresses a rally in Nashville, TN in March 2017.

Photo released by the Office of the President of the United States via Wikimedia Commons.

What might a second Trump White House be like? In his new book, At War with Ourselves: My Tour of Duty in the Trump White House, Lt. Gen. H.R. McMaster, who served as national security adviser to Donald Trump (for one year), characterizes Oval Office meetings as “exercises in competitive sycophancy” where advisers would greet him with lines like “your instincts are always right” or “no one has ever been treated so badly by the press”.

Trump, meanwhile, would come up with crazy concepts, and float them: “Why don’t we just bomb the drugs?” (Also: “Why don’t we take out the whole North Korean Army during one of their parades?”)

This is one man’s account, of course. McMaster’s word should not be taken as gospel, and some of his frustration might stem from his dismissal, or his foreign-policy prescriptions being at times ignored by his boss. But it’s a somewhat revealing look behind the curtain at policy-setting in a White House helmed by an especially mercurial commander in chief, who “enjoyed and contributed to interpersonal drama in the White House and across the administration”.

It also shows how quickly Trump fantasies have percolated through the Republican Party, namely the “let’s just bomb Mexico to get rid of the cartels” line, which Trump has been toying with since roughly 2019 (or possibly more like 2017, after he chatted with Rodrigo Duterte, former president of the Philippines, who had promised to kill 100,000 drug traffickers during his first six months as president). A few years prior, in 2015, he had suggested that Mexico was sending rapist and drug-traffickers across the southern border, and that we’d need to build a wall between the two countries, but it wasn’t until nine American citizens were killed in Mexico that Trump trotted out the idea of declaring cartels foreign terrorist organizations and using military might to eradicate them.

Trump’s line from 2019 has now become standard fare, notes The Economist: The Republican primary debates included lots of tough talk on Mexico, specifically on the bombing front, with Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis claiming he’d send special forces down there on Day One. Right-wing think tanks have embraced the messaging, with articles headlined “It’s Time to Wage War on Transnational Drug Cartels”. Taking cues from other members of her party, Georgia Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene asked why “we’re fighting a war in Ukraine, and we’re not bombing the Mexican cartels”. Whether it’s economic protectionism (10 percent across-the-board tariffs, with 60 percent tariffs imposed on Chinese imports) or Mexico-bombing, Trump has near-magical abilities to get other members of his party to accept something previously regarded as absurd.

Then I’ll Take Her When You’re  Dead

Dead !

!

Jill Bearup

Published May 13, 2024Ah, Captain Blood. Swords, sand, and piratical shenanigans. Let’s do this.

The Fight Master Vol 1 Issue 1: https://mds.marshall.edu/fight/1/

Buy my book: books2read.com/juststabmenow (or try your local Amazon/bookstore)

Dead

Dead !

! QotD: NFL team owners

It’s probably also worth noting that the new Vikings owner is very big on family. By my count, [new Minnesota Vikings majority owner] Zygi [Wilf] used the word “family” 1,068 times during the 45-minute interview session. He mentioned his family, the Vikings family, his partners’ families, local families and the family business.

Asked about meeting the other NFL owners for the first time, Wilf said — you guessed it — they are like a family. Which I can see, particularly when I envision the Corleone family.

Tom Powers, “No news is good snooze with Wilf”, St. Paul Pioneer Press, 2005-06-17.

August 27, 2024

Was 1974 the worst year in British politics or just the worst year so far?

I wasn’t in the UK in 1974 (although I did spend a couple of dystopian weeks there in January 1979), so I don’t know from personal experience just how bad things were, but as Ed West considers Dominic Sandbrook’s very informative social history Seasons in the Sun, he certainly helps make a strong case for it:

One of my favourite moments from reading Fever Pitch as a teenager was the passage where Nick Hornby and a friend bunk off school to watch Arsenal play West Ham, a game which was being held on a weekday afternoon because there wasn’t enough electricity for the floodlights. Britain was enduring a three-day week due to the energy crisis, and assuming the ground would be empty, Hornby is stunned to find it packed with 60,000 people, all skiving off work, and he recalls his hypocritical juvenile disgust at the idleness of the British public.

The scene encapsulates the comic crapness of that period, one that many of us have enjoyed laughing at with the recent Rest is History series on 1974. I began reading Sandbrook’s book Seasons in the Sun afterwards, from where the material for the series was drawn; the early chapters comprise a highly entertaining account of what he described on the podcast as “the worst year in British politics”. Reassuring, perhaps, for those of us inclined towards pessimism, although to paraphrase Homer Simpson, perhaps it was only the worst year so far.

Nineteen-seventy-four saw two elections, the first of which ended in a hung parliament, with Labour as the largest party, and the second with Harold Wilson winning with a majority of 3. These were fought between parties led by exhausted leaders who had run out of ideas, with a third, the Liberals headed by Jeremy Thorpe, soon to be notorious as a dog killer. Britain had declined from the richest country on the continent to one of the poorest in western Europe, and its economy seemed to be falling apart.

During his troubled four years in office Edward Heath had called a state of emergency several times, culminating in ration cards for petrol and power restrictions. In 1973 Heath had “told his Chancellor, Anthony Barber, to go for broke”, Sandbrook writes: “It was one of the greatest economic gambles in modern history: while credit soared and the money supply boomed, Heath hoped to keep inflation down through an elaborate system of wage and price controls”. By October that year, “his hopes were unravelling at terrifying speed”.

The “Barber boom” led to “house prices surging by 25 per cent in just six months, the cost of imports rocketing and Britain’s trade balance plunging deep into the red”. Yet just a week after Heath had published details of his “Stage Three” incomes policy, “the Arab oil exporters in the OPEC cartel announced a stunning 70 per cent increase in the posted price of oil, punishing the West for its support for Israel. It was a devastating blow to the world economy, but nowhere was its impact greater than in Britain.”

The stock market lost a quarter of its value in just a month, while by January 1974 share prices had fallen by almost half in under two years. Just before Christmas, the government cut spending by 4 per cent, and Labour’s Shadow Chancellor, Denis Healey, “warned his colleagues that Britain stood on the brink of an ‘economic holocaust'”. Nine out of ten people told a Harris poll that “things are going very badly for Britain” and nearly as many foresaw no improvement in the coming year. They turned out to be correct.

Amid trouble with the National Union of Mineworkers, in November 1973 “Heath announced his fifth state of emergency in barely four years. Floodlighting and electric advertising were banned; behind the scenes, the government began printing petrol ration cards. As the railwaymen voted to join the miners in pursuit of higher pay, it seemed that Britain was sliding into darkness. Offices were ordered to turn down their thermostats, while the BBC and ITV were banned from broadcasting after 10.30 at night. On New Year’s Day, with fuel supplies running dangerously low, the entire nation went on a three-day working week.” Happy days.

Britain as the modern Panopticon

Jeremy Bentham proposed a new kind of prison in the 1700s, one where all of the prisoners in their cells were under constant observation by the guards. What sounds like a horrific way to live to any sensible rational person seems to have a fascinating appeal to the kind of micromanaging, busybody control freak who runs for office in British politics today:

In Britain authorities use cameras to monitor private individuals in real time. They track cars using number plate software, and human beings using facial recognition software and analysis of gait.

The rationale for these intrusive measures is to prevent illegal activity as well as recording crimes for use in trials.

This troubles many since it places unsupervised control mechanisms in the hands of politicians and authorities increasingly out of touch with the interests of the majority.

Full-spectrum surveillance

The British Government has recently threatened to use this surveillance technology to clamp down on “extremists”.

Currently that means anti-immigration protestors, although there is provision for “anti-establishment” protestors too.

There is much Britain’s political class will not tolerate in the people who elevate them to power.

They have promised to relentlessly hound detestables using advanced spy technology, principally facial recognition software. This is specifically designed to identify individuals and track their movements in real time.

None of this has been requested by the public, and polls reflect considerable unease, particularly with facial recognition software, a powerful tool few are comfortable with.

Advocates of surveillance claim this erosion to our privacy is a necessary step to tackle crime. Cameras enable the police and authorities to identify criminals as well as detect and record the crimes they commit.

To the casual observer it sounds plausible and even reasonable. We won’t be using it to spy on you, only them. It has some public benefits.

This seems like a workable idea. So why is it so useless at stopping a very visible crime?

Food at your regional end-of-summer fair/exhibition/extravaganza

For us in the Greater Toronto Area, it’s the Canadian National Exhibition but for a lot of Americans it’s their State Fair. James Lileks considers the sad fact that the interesting and exotic food choices at these shindigs is … overrated:

“Fruity Cereal Tenders”, one of the weird food offerings at the 2024 Canadian National Exhibition in Toronto.

Photo from blogTO, “Here’s all the outrageous food and drinks at the 2024 CNE”

I do not understand is why people go to the Fair and queue up at the hamburger stand. I often think this as I am in the queue at the hamburger stand.

After all, there’s so much more to eat. Corn dogs, for example. A low-flavor tube of minced abattoir sweepings, dipped in batter, plunged in oil, and served on a stick with a sharp point on the end. When you get to the last few bites, you either have to shimmy the butt of the corn dog up the skewer, or sword-swallow the thing so the sharp point spears your soft palate. Condiments? Why, yes — a smear of ketchup, or a smear of mustard, or, if you’re one of those people who believe in grabbing life by the lapels and shouting give me all you got, you have both.

Never in my life have I ever thought “I could go for a Corn Dog right about now,” but put me at the Fair and I have to eat one within five minutes of entering the grounds. It’s like the pistol shot that starts a race, and, like a bullet, goes through you just as fast.

It’s the same with mini-donuts. When I was doing the trivia contest at the newspaper stage, one of the questions was “how many mini-donuts can you eat before you are overcome with self-loathing?” The answer varies, I suppose, according to how much pre-existing self-loathing you bring to the job. Maybe you’re already hating yourself for eating a Sweet Martha’s bucket of cookies, a popular item at the fair. It has a handle so you can amble around as you eat. One of these years I expect it will come with a yoke and a spring-loaded tab that pops them in your you at present intervals, for hands-free consumption. My friends, a bucket of cookies is to personal girth management as a cup of quarters at a casino is to financial planning.

This year’s hot new item is “deep fried ranch dressing”, which seems impossible, like “sugar-dusted humidity on a stick”. How do they do that? Just pour the ranch in the roiling oil and and scoop out a globule?

“Well, first you shape the dressing into patties, then — ”

Wait, no, you cannot shape dressing. It defies your attempts to give it form, unless you’ve added a thickening element. (Of course, everything they serve at the Fair is a thickening element, in a sense.) It’s supposed to be delicious, but I wouldn’t eat one without first unbuttoning my shirt and smearing conducting gel on my chest, just to save time. Maybe even draw a dotted line on my sternum.

Updated to add the correct URL. Management would like to apologize for this error. The people responsible for it have been sacked.

Finland’s Prototype Belt-Fed GPMG: L41 Sampo

Forgotten Weapons

Published May 13, 2024During the 1930s, there was interest in Finland in replacing the Maxim heavy machine gun with something handier and more mobile. There were experiments with large drum magazines for the LS-26 light machine gun, but these were not satisfactory. Aimo Lahti began to work on a gas-operated GPMG, but lack of funding and competing priorities led to it having slow progress until the eve of the Winter War. By the time the gun was completed and the first preproduction batch ready for troop trials, the Continuation War was underway.

Twenty eight of the L41 Sampo machine guns were sent out to a variety of units for field testing in the fall of 1942, and the guns were generally well liked, although not perfect. Before improvements and full-scale production could begin, though, the Finnish military was basically distracted by an alternative possibility of procuring MG42 receivers from Germany and building them into complete guns in 7.62x54R. At least one such prototype was completed, and that project caused the L41 program to stall. By the time it might have progressed, the war was going rather badly for Germany and the possibility of getting receivers was basically gone. The L41 never did see further refinement or production, although the trials guns remained in service with their units, in a few cases right until the end of the war.

Mechanically, the L41 is a fascinating hybrid of Bren/ZB and Maxim elements, and incredibly sturdily built. Only seven are know to survive today, six in Finland and this one in the UK. Thanks to the British Royal Armouries for giving me access to it to film for you!

(more…)