Sieges are probably about a year or so younger than the first fortified village — as soon as someone came up with the bright idea of throwing a wall around it for protection, some equally bright spark likely started coming up with ways to get inside that wall. In The Critic, Peter Caddick-Adams considers the eclipse and return of siege warfare in Europe in reviewing Iain MacGregor’s The Lighthouse of Stalingrad and Prit Buttar’s To Besiege a City: Leningrad 1941-42:

The history of war is never far removed from battles for cities. Many of us, of whatever creed, were brought up on the story of the walls of Jericho tumbling after the Israelites marched around the stronghold once a day for six days, seven times on the seventh day, and then blew their trumpets. Though no archaeological evidence at Tell es-Sultan, in modern Palestine, corroborates the arresting visual image related in Joshua, Chapter 6, diggers have uncovered a range of defensive stone and brick walls dating back to 8,000 BC. It indicates that even 10,000 years ago, the ancients indulged in the odd siege when the mood took them. The biblical story also introduces us to the concept of intimidation, today fashionably called “psychological warfare”.

The much younger fortress of Troy provides insights into another city-focussed era of battles. Beneath today’s Hisarlik in northern Turkey are nine archaeological layers. Troy VIII was the alluring city of Classical and Hellenistic times, as portrayed in the Iliad, Homer’s Odyssey and Virgil’s Aeneid. The Romans took the lessons of Homeric Troy seriously and clad all their major settlements with defensive walls, as any exploration of Canterbury, Chester or York will confirm. These acted as magnets for opponents, as in Boudicca’s revolt of AD 60–61. Cities such as Colchester, London and St Albans were sacked, as much for what they represented as for their physical presence.

When the Normans arrived in their longships, they imported the concept of stone castles to control the newly conquered English. Their walled cities would be ungraded and contested scores of times over the succeeding six centuries. Henry V’s siege of Harfleur (modern Le Havre) in 1415, the beginning of the Agincourt campaign famously depicted in Shakespeare’s play, underlined the drawback of traditional sieges. They took longer and were usually far costlier than expected. Several thousand men camped in a small area with no knowledge of hygiene inevitably resulted in a high mortality rate amongst the attackers before a shot was fired.

Harfleur was also the first time an English army made use of gunpowder artillery in a siege, a technology that had trickled its way across the world from China. Powder and fuse heralded events 38 years later, when an Ottoman army shook the Christian world to its core by breaching the massive walls of Constantinople (Istanbul) after a 53-day bombardment using cannons. On Tuesday, 29 May 1453, stone finally gave way to bronze and iron, finishing the last remnant of the Roman Empire. Europe was never quite the same again. Fortress architecture started to employ breadth, using earthen ramparts and ditches, rather than height.

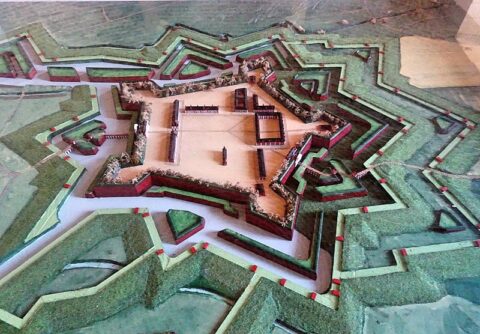

Strategy for urban warfare intensified during the lifetime of the French fortress engineer Vauban (1633–1707), who used landscaped terrain as well as geometrically designed defensive walls to deter would-be besiegers. When viewed from above, his fortification designs resemble starfish. So successful were his tactics that sieges, always costly and time-consuming, lessened in importance. His contemporary Marlborough recognised that on any cost-benefit analysis, Vauban had rendered sieges militarily unprofitable, restoring manoeuvre to campaigns.

Subsequent wars fought in the Napoleonic era, the Crimea, between the American North and South, and by Prussia generally reflected this return to mobility. There was the odd attritional discrepancy with the 1854–55 siege of Sevastopol, that of Petersburg in 1864–65 and Paris in 1870–71. Cities were still fought for, but usually contests were removed away from the walls, where forces could conduct wide sweeping manoeuvres, such as Leipzig in 1813 or Ypres in the Great War. As weapons grew more accurate and their munitions heavier, fortifications broadened and sank into the ground, culminating in the trenches of 1914–18. In this era, dominance of terrain became the hallmark, and it was virtually siege-free.

It was remarkable that urban warfare returned on an industrial scale during the Second World War, a time usually associated with blitzkrieg and rapid tank thrusts. This happened at Leningrad, Sevastopol and Stalingrad in the East; at Ortona and Cassino in Italy, Caen; Carentan and St Lo in Normandy; in Aachen and later assaults on Aschaffenburg and Cologne, Magdeburg, Leipzig and Berlin in 1945. Subsequent NATO doctrine for the defence of central Europe focussed on the threat of more attrition. Plans were devised to defend quite small localities, putting grit in the Soviet steamroller and making the cost of attacking Western towns and cities prohibitive.