In the latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes goes a long way in both time and space away from his normal Industrial Revolution beat to consider what might happen as humans attempt to colonize Mars:

![]()

The first true-colour image generated using the OSIRIS orange (red), green and blue colour filters. The image was acquired on 24 February 2007 at 19:28 CET from a distance of about 240 000 km; image resolution is about 5 km/pixel.

Photo taken by the ESA Rosetta spacecraft during a planetary flyby.

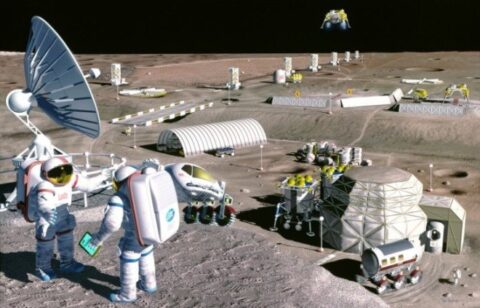

The other week I attended an unconference, which had a session on the implications of establishing colonies on other planets. Although this was largely meant to be about the likely impact on Earth’s natural environment — what will be the impact of extracting raw materials from asteroids and other planets? — some of the discussion reminded me of the challenges faced by the long-distance explorers, merchants, and colonists of four hundred years ago. There are quite a few parallels I can see between travelling to Mars, say, in a hundred years’ time, and travelling between continents in the age of sail.

For a start, there’s the seasonality and duration of the voyages. European ships headed for the Indian Ocean had to time their voyages around the monsoon season; trips across the Atlantic were limited to just half the year because of hurricanes. Round-trips took years. Similarly, the departure window for a voyage from Earth to Mars only comes around once every 26 months, and even the most optimistic estimates place eventual journey times at about 4-6 months. Supposing that Mars can be permanently settled, any colony there will likely be extremely dependent on the regular arrival of resupply craft. There’s only so long that any group can survive in a hostile environment on their own.

[…]

The Portuguese had once been the only Europeans to trade directly into the Indian Ocean, but the structure of their trade — essentially a state-run monopoly with some licensed private merchants — was unable to compete with the arrival of the Dutch. The initial Dutch forays into the Indian Ocean in the 1590s had originally been financed by lots of different companies, often associated with particular cities — similar to the proliferation of billionaire-led space exploration companies today. But the Dutch soon recognised that such a high-risk trade would only be able to survive if it came with correspondingly high rewards — rewards that could only be guaranteed by eliminating domestic competitors (and if possible, foreign ones too). They therefore amalgamated all of the smaller concerns into a single company with a state-granted monopoly on all of the nation’s trade with the region. In this, they actually copied the English model, but then outdid them in terms of the organisation and financing of that company […].

Are we likely to see a similar move towards state-granted monopoly corporations when it comes to space colonisation? I suspect it depends on the potential rewards, and on the strength of the competition. There is certainly precedent for incentivising risky and innovative ventures in this way, through the granting of patent monopolies. Patents for inventions in the English tradition originally even had their roots in patents for exploration. I would not be surprised if such policies end up being used again by countries that are late-comers to the space race, perhaps by granting domestic monopolies over the extraction of resources from particular planets or moons. Although direct state funding can help in being first, like they did for Spain and Portugal in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, state-granted monopolies for private actors may again end up being the ideal catch-up tool for laggards, as they were for the English and the Dutch.

How the monopolies are managed will also matter. The English East India Company, for example, was initially more focused on rewarding its shareholders than it was on investing in the full infrastructure with which to dominate a trade route. The Dutch company, by contrast, from the get-go was part of a more coordinated imperial strategy — one that sought to systematically rob the Portuguese of their factories and forts, to project force with the aid of the state. Indeed, if there’s one big lesson for the geopolitics of space, it’s that far-flung empires can be extremely fragile, with plenty of opportunities for late-arriving interlopers to take them over.

Although it’s difficult to imagine space colonies being able to become self-sufficient any time soon, it seems likely that those controlled by particular companies or countries may occasionally be persuaded — by bribes or by force — to defect. What’s to stop them when they’re hundreds of millions of kilometres away from any punishment or help? Ill-provisioned factors, forts, or colonies happily switched sides to whoever might provision them better. As I mentioned last week, such problems curtailed the ambitions of other would-be colonial powers, like the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia. When the Dutch turned up in the Indian Ocean, many of the Portuguese forts they threatened simply surrendered.

I bow to Anton’s far greater historical knowledge in most things, but state monopolies in the 16th to 19th centuries were very different creatures than their potential modern equivalents, and the much more comprehensive degree of state control of the economy now would probably mean that a state monopoly over extraterrestrial activities would be a worst-possible outcome. The greater the powers in the hands of the state, in almost every case, the worse all state-controlled activities have become. The incentives of civil servants are vastly different than those of individuals or businesses and are farcically incompatible with the risk-taking necessary on a dangerous frontier.