TimeGhost History

Published 6 Apr 2025By 1948, Britain’s conflicting promises in Palestine have created a powder keg ready to explode. Contradictory pledges made to Arabs and Zionists during WWI set the stage for rising tensions, violent uprisings, and ultimately civil war. As Britain prepares to withdraw and the UN votes for partition, violence escalates, and the hope for a peaceful, free Palestine shatters into chaos. How did the broken promises lead to such tragedy?

(more…)

April 8, 2025

The Broken Promise of Free Palestine – W2W 19 – 1948 Q1

April 7, 2025

QotD: The new Neolithic agrarian villages allowed for the development of the parasitic state

… despite all these drawbacks, people whose distant ancestors had enjoyed the wetland mosaic of subsistence strategies were now living in the far more labor-intensive, precarious confines of the Neolithic village, where one blighted crop could spell disaster. And when disaster struck, as it often did, the survivors could melt back into the world of their foraging neighbors, but slow population growth over several millennia meant that those diverse niches were full to the bursting, so as long as more food could be extracted at a greater labor cost, many people had incentive to do so.

And just as this way of life — [Against the Grain author James C.] Scott calls it the “Neolithic agro-complex”, but it’s really just another bundle of social and physical technologies — inadvertently created niches for the weeds that thrive in recently-tilled fields1 and the fleas that live on our commensal vermin, it also created a niche for the state. The Neolithic village’s unprecedented concentration of manpower, arable land, and especially grain made the state possible. Not that the state was necessary, mind you — the southern Mesopotamian alluvium had thousands of years of sedentary agriculturalists living in close proximity to one another before there was anything resembling a state — but Scott writes that there was “no such thing as a state that did not rest on an alluvial, grain-farming population”. This was true in the Fertile Crescent, it was true along the Nile, it was true in the Indus Valley, and it was true in the loess soils of “Yellow” China.2 And Scott argues that it’s all down to grain, because he sees taxation at the core of state-making and grain is uniquely well-suited to being taxed.

Unlike cassava, potatoes, and other tubers, grain is visible: you can’t hide a wheatfield from the taxman. Unlike chickpeas, lentils, and other legumes, grain all ripens at once: you can’t pick some of it early and hide or eat it before the taxman shows up. Moreover, unhusked grain stores particularly well, can be divided almost infinitely for accounting purposes (half a cup of wheat is a stable and reliable store of value, while a quarter of a potato will rot), and has a high enough value per unit volume that it’s economically worthwhile to transport it long distances. All this means that sedentary grain farmers become taxable in a way that hunter-gatherers, nomadic pastoralists, swiddeners, and other “nongrain peoples” are not, because you know exactly where to find them and exactly when they can be expected to have anything worth taking. And then, of course, you’ll want to build some walls to protect your valuable grain-growing subjects from other people taking their grain (and also, perhaps, to keep them from running for the hills), and you’ll want systems of measurement and record-keeping so you know how much you can expect to get from each of them, and pretty soon, hey presto! you have something that looks an awful lot like civilization.

The thing is, though, that Scott doesn’t think this is an improvement. It certainly wasn’t an improvement for the new state’s subjects, who were now forced into backbreaking labor to produce a grain surplus in excess of their own needs (and prevented from leaving their work), and it wasn’t an improvement for the non-state (or, later, other-state) peoples who were constantly being conquered and relocated into the state’s core territory as new domesticated subjects to be worked just like its domesticated animals. In fact, he goes so far as to suggest that our archaeological records of “collapse” — the abandonment and/or destruction of the monumental state center, usually accompanied by the disappearance of elites, literacy, large-scale trade, and specialist craft production — in fact often represent an increase in general human well-being: everyone but the court elite was better off outside the state. “Collapse”, he argues, is simply “the disaggregation of a complex, fragile, and typically oppressive state into smaller, decentralized fragments”. Now, this may well have been true of the southern Mesopotamian alluvium in 3000 BC, where every statelet was surrounded by non-state, non-grain peoples hunting and fishing and planting and herding, but it’s certainly not true of a sufficiently “domesticated” people. Were the oppida Celts, with their riverine trading networks, better off than their heavily urbanized Romano-British descendants? Well, the Romano-Britons had running water and heated floors and nice pottery to eat off of and Falernian wine to drink, but there’s certainly a case to be made that these don’t make up for lost freedoms. But compare them with the notably shorter and notably fewer involuntarily-rusticated inhabitants of sub-Roman Britain a few hundred years later and even if you don’t think running water is worth much (you’re wrong), you have to concede that the population nosedive itself suggests that there is real human suffering involved in the “collapse” of a sufficiently widespread civilization.3

But even this is begging the question. We can argue about the relative well-being of ordinary people in various sorts of political situations, and it’s a legitimately interesting topic, both in what data we should look at — hunter-gatherers really do work dramatically less than agriculturalists4 — and in debating its meaning.5 And Scott’s final chapter, “The Golden Age of the Barbarians”, makes a pretty convincing case that they were materially better off than their state counterparts, especially once the states really got going and the barbarians could trade with or raid them to get the best of both worlds! But however we come down on all these issues, we’re still assuming that the well-being of ordinary people — their freedom from labor and oppression, their physical good health — is the primary measure of a social order. And obviously it ain’t nothing — salus populi suprema lex and so forth — but man does not live by

breada mosaic of non-grain foodstuffs alone. There are a lot of important things that don’t show up in your skeleton! We like civilization not because it produces storehouses full of grain and clay tablets full of tax records, but because it produces art and literature and philosophy and all the other products of our immortal longings. And, sure, this was largely enabled by taxes, corvée labor, conscription, and various forms of slavery, but on the other hand we have the epic of Gilgamesh.6 And obviously you don’t get art without civilization, which is to say the state. Right?Jane Psmith, “REVIEW: Against the Grain, by James C. Scott”, Mr. and Mrs. Psmith’s Bookshelf, 2023-08-21.

1. Oats apparently began as one of them!

2. It was probably also true in Mesoamerica and the Andes, where maize was the grain in question, but Scott doesn’t get into that.

3. No, the population drop cannot be explained by all the romanes eunt domus.

4. That famous “twenty hours a week” number you may have heard is bunk, but it’s really only about forty, and that includes all the housekeeping, food preparation, and so forth that we do outside our forty-hour workweeks.

5. For example, does a thatched roof in place of ceramic tiles represent #decline, or is it a sensible adaptation to more local economy? Or take pottery, which is Bryan Ward-Perkins’s favorite example in his excellent case that no really, Rome actually did fall: a switch in the archaeological record from high-quality imported ceramics to rough earthenwares made from shoddy local clays is definitely a sign of societal simplification, but it isn’t prima facie obvious that a person who uses the product of an essentially industrial, standardized process is “better off” than someone who makes their own friable, chaff-tempered dishes.

6. Or food rent and, uh, all of Anglo-Saxon literature, whatever.

April 3, 2025

1947 Newscast: Spies, Aliens, and Collapsing Empires! – W2W 18

TimeGhost History

Published 2 Apr 20251947 is a pivotal year: The British Empire crumbles as India and Pakistan gain independence amidst violence and mass migration. Truman launches a Cold War against Soviet communism, while spies infiltrate governments worldwide. Nations sign treaties reshaping Europe; Chuck Yeager breaks the sound barrier, and rumours swirl of aliens crashing at Roswell. Join us for the headlines that reshaped history!

(more…)

March 25, 2025

QotD: The nature of kingship

As I hammer home to my students, no one rules alone and no ruler can hold a kingdom by force of arms alone. Kings and emperors need what Hannah Arendt terms power – the ability to coordinate voluntary collective action – because they cannot coerce everyone all at once. Indeed, modern states have far, far more coercive power than pre-modern rulers had – standing police forces, modern surveillance systems, powerful administrative states – and of course even then rulers must cultivate power if only to organize the people who run those systems of coercion.

How does one cultivate power? The key factor is legitimacy. To the degree that people regard someone (or some institution) as the legitimate authority, the legitimate ruler, they will follow their orders mostly just for the asking. After all, if a firefighter were to run into the room you are in right now and say “everybody out!” chance are you would not ask a lot of questions – you would leave the room and quickly! You’re assuming that they have expertise you don’t, a responsibility to fight fires, may know something you don’t and most importantly that their position of authority as the Person That Makes Sure Everything Doesn’t Burn Down is valid. So you comply and everyone else complies as a group which is, again, the voluntary coordination of collective action (the firefighter is not going to beat all of you if you refuse so this isn’t violence or force), which is power.

At the same time, getting that compliance, for the firefighter, is going to be dependent on looking the part. A firefighter who is a fit-looking person in full firefighting gear who you’ve all seen regularly at the fire station is going to have an easier time getting you all to follow directions than a not-particularly-fit fellow who claims to be a firefighter but isn’t in uniform and you aren’t quite sure who they are or why they’d be qualified. The trappings contribute to legitimacy which build power. Likewise, if your local firefighters are all out of shape and haven’t bothered to keep their fire truck in decent shape, you – as a community – might decide they’ve lost your trust (they’ve lost legitimacy, in fact) and so you might replace them with someone else who you think could do the job better.

Royal power works in similar ways. Kings aren’t obeyed for the heck of it, but because they are viewed as legitimate and acting within that legitimate authority (which typically means they act as the chief judge, chief general and chief priest of a society; those are the three standard roles of kingship which tend to appear, in some form, in nearly all societies with the institution). The situation for monarchs is actually more acute than for other forms of government. Democracies and tribal councils and other forms of consensual governments have vast pools of inherent legitimacy that derives from their government form – of course that can be squandered, but they start ahead on the legitimacy game. Monarchs, by contrast, have to work a lot harder to establish their legitimacy and doing so is a fairly central occupation of most monarchies, whatever their form. That means to be rule effectively and (perhaps more importantly) stay king, rulers need to look the part, to appear to be good monarchs, by whatever standard of “good monarch” the society has.

In most societies that has traditionally meant that they need not only to carry out those core functions (chief general, chief judge, chief priest), but they need to do so in public in a way that can be observed by their most important supporters. In the case of a vassalage-based political order, that’s going to be key vassals (some of whom may be mayors or clerics rather than fellow military aristocrats). We’ve talked about how this expresses itself in the “chief general” role already.

I’m reminded of a passage from the Kadesh Inscription, an Egyptian inscription from around 1270 BC which I often use with students; it recounts (in a self-glorifying and propagandistic manner) the Battle of Kadesh (1274 BC). The inscription is, of course, a piece of royal legitimacy building itself, designed to convince the reader that the Pharaoh did the “chief general” job well (he did not, in the event, but the inscription says he did). What is relevant here is that at one point he calls his troops to him by reminding them of the good job he did in peace time as a judge and civil administrator (the “chief judge” role) (trans. from M. Lichtheim, Ancient Egyptian Literature, vol 2 (1976)):

Did I not rise as lord when you were lowly,

and made you into chiefs [read: nobles, elites] by my will every day?

I have placed a son on his father’s portion,

I have banished all evil from the land.

I released your servants to you,

Gave you things that were taken from you.

Whosoever made a petition,

“I will do it,” said I to him daily.

No lord has done for his soldiers

What my majesty did for your sakes.Bret Devereaux, “Miscellanea: Thoughts on CKIII: Royal Court”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2022-02-18.

March 18, 2025

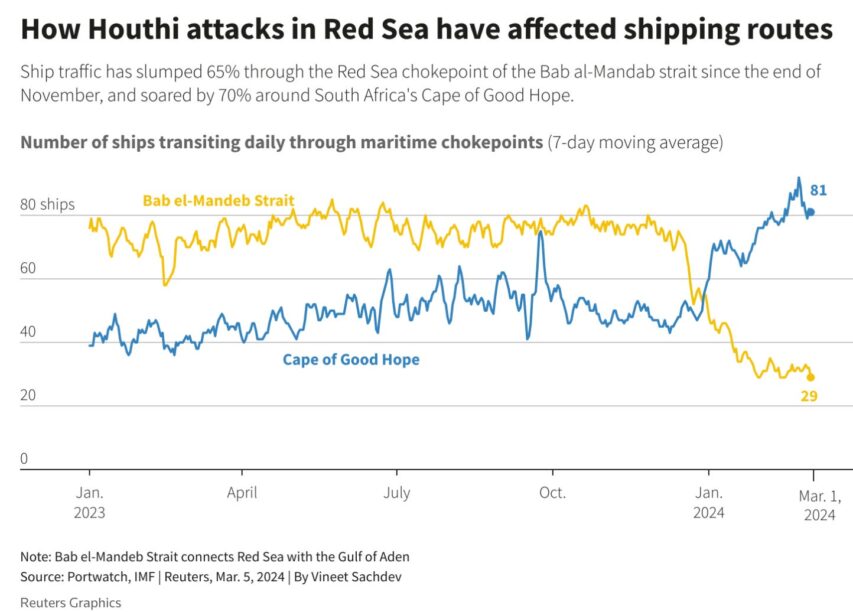

Getting rid of Houthi and the Blowfish

It has been alarming just how long the west — and especially the United States — have been willing to put up with Houthi attacks on shipping going through the Red Sea. President Trump has indicated that American patience has run out, as CDR Salamander discusses:

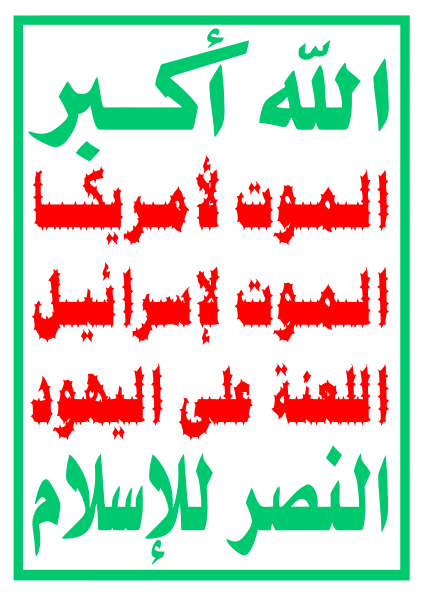

The Houthi Ansarullah “Al-Sarkha” banner. Arabic text:

الله أكبر (Allah is the greatest)

الموت لأمريكا (death to America)

الموت لإسرائيل (death to Israel)

اللعنة على اليهود (a curse upon the Jews)

النصر للإسلام (victory to Islam)

Image and explanatory text from Wikimedia Commons.

… in the almost 18 months since the Houthi rebels have been attacking Western shipping in the Red Sea, we have mostly been playing defense.

Why have we been playing defense? The Biden Administration, like the Obama Administration, was worm-ridden with Iranian accommodationalists. The Houthi, like Hamas and Hezbollah, are Iranian proxies.

After the murder, rape, slaughter, and kidnapping from Gaza into Israel on October 7th, 2023 by Iranian proxies, the Houthi started their campaign of support — as directed by Iran — by attacking shipping in the Red Sea.

It could not be ignored, but we never took the needed action. We did not even do half-measures. At best we did quarter-measures.

The attacks continued and our credibility on the world stage degraded in proportion to that.

As we have discussed often here, we have a few thousand years of dealing with piracy and bad-faith actors on the high seas. It has direct costs in commerce, treasure, and lives.

This cannot be allowed to continue.

Over the weekend, the new Trump Administration put down a marker. We seem to have ratcheted things up a bit. Not much available on open source, but over the weekend, CENTCOM put out a few things;

CENTCOM Forces Launch Large Scale Operation Against Iran-Backed Houthis in Yemen On March 15, U.S. Central Command initiated a series of operations consisting of precision strikes against Iran-backed Houthi targets across Yemen to defend American interests, deter enemies, and restore freedom of navigation.

[…]

Where is all this going? Well, let’s establish a few things first.

- Clearly what we were doing was not working.

- The Houthi are a 4th rate non-naval power. We like to tell everyone that, though we are the world’s second largest navy, we are the most capable. If we can’t keep the Houthi away from shipping through a major Sea Line of Communication, then why should anyone expect we could do more.

- Europe won’t/can’t help. They not only lack the capability to project power ashore against the Houthi to any reasonable measure, they lack the will.

- China does not care. It does not impact them. They benefit from this chaos against the West.

- Russia thinks this is wonderful.

- Iran can’t believe we are letting this go on. The Houthi are the last significant proxy, so they will do all they can to keep them going.

The lines are fairly clear right now. Not much room to maneuver. Looks like we will be at this for awhile. More extended range time.

March 12, 2025

Free speech in Canada takes yet another hit, as Palestinian activists granted special protections

In the National Post, Tristin Hopper outlines the jaw-dropping contents of the Guide to Understanding and Combatting Islamophobia published by the federal government recently:

The federal government has dropped a new guide that, according to critics, deems it “racist” to criticize Palestinian advocacy or extremism.

The guide also defines both “sharia” and “jihad” as benign terms that are misrepresented by Westerners, with sharia defined as a means “to establish justice and peace in society”.

It’s contained in “The Canadian Guide to Understanding and Combatting Islamophobia“, a document published last week by the Department of Canadian Heritage.

The report endorses the idea of “anti-Palestinian racism”, an activist term with such a broad definition that it technically deems any criticism of Palestinians or “their narratives” to be racist.

“Public discourse often unfairly associates Palestinian and Muslim identities with terrorism,” reads the guide.

The new guide specifically links to a definition of the term circulated by the Arab Canadian Lawyers Association. Their 99-word definition says that it’s racist to link the Palestinian cause to terrorism, to describe it as “inherently antisemitic” or to say that Palestinians are not “an Indigenous people”.

The term is broad enough that merely acknowledging the existence of Israel could fall under its rubric. The definition describes the Jewish state as “occupied and historic Palestine”, and its creation as “the Nakba” (catastrophe). “Denying the Nakba” is specifically cited as one of the markers of “anti-Palestinian racism”.

In a March 4 statement criticizing the new federal report, the Centre for Israel and Jewish Affairs (CIJA) said that the term is so vague that “denouncing Hamas – the terrorists behind the October 7 massacre – could be portrayed as an act of racism”.

The new report was praised, meanwhile, by the vocally anti-Israel Centre for Justice and Peace in the Middle East, which called Ottawa’s embrace of the term anti-Palestinian racism “groundbreaking.”

“We are extremely pleased that Canada, through this guide, finally recognizes the unique racism that Palestinians experience daily,” said the group’s acting president Michael Bueckert.

The federal government’s new guide writes that Canada’s “understanding of anti-Palestinian racism” is growing, and directs readers to a 2022 report on the phenomenon by the Arab Canadian Lawyers Association.

March 3, 2025

Europe’s Imperial Giants: On the Brink of Collapse? – W2W 09 Q4 1946

TimeGhost History

Published 2 Mar 2025In 1946, Britain, France, and the Netherlands fight to regain control over shattered colonies — from Indonesia’s revolt to Vietnam’s war with France. Meanwhile, the U.S. and USSR maneuver to shape these emerging nations for their own global interests. Will independence spark true liberation, or will it simply swap one master for another?

(more…)

All The Basics About XENOPHON

MoAn Inc.

Published 7 Nov 2024I actually found this video really tricky considering I want to go into the texts of Xenophon and if I told you everything about the march of the ten thousand then I would have just told you the whole Anabasis?? Which defeats the whole purpose of an introductory video?? So I PROMISE more clarity will come in future videos as Xenophon himself breaks down his journey home from Persia and why they were there in the first place. Therefore, you have ALL OF THAT to look forward to — coming soon!!!

(more…)

February 28, 2025

Everyday Life in the Roman Empire – An Empire of Peoples

seangabb

Published 28 Aug 2024The Roman Empire had a geographical logic, but was an endlessly diverse patchwork of linguistic, ethnic and religious groups. In this lecture, Sean Gabb describes the diversity:

Geographical Logic – 00:00:00

Linguistic Diversity – 00:06:57

Italy – 00:12:46

Greece – 00:17:23

Greeks and Romans – 00:21:01

Egypt – 00:28:24

Greeks, Romans, Egyptians – 00:33:00

North Africa – 00:37:27

The Jews – 00:41:20

Greeks, Romans, Jews – 00:44:10

Gaul – 00:50:36

Britain – 00:52:26

Greeks, Romans, Britons – 00:54:58

The East – 00:59:22

Bibliography – 01:01:20

(more…)

February 23, 2025

QotD: The Hellenistic army system as a whole

I should note here at the outset that we’re not going to be quite done with the system here – when we start looking at the third and second century battle record, we’re going to come back to the system to look at some innovations we see in that period (particularly the deployment of an enallax or “articulated” phalanx). But we should see the normal function of the components first.

No battle is a perfect “model” battle, but the Battle of Raphia (217BC) is handy for this because we have the two most powerful Hellenistic states (the Ptolemies and Seleucids) both bringing their A-game with very large field armies and deploying in a fairly standard pattern. That said, there are some quirks to note immediately: Raphia is our only really good order of battle of the Ptolemies, but as our sources note there is an oddity here, specifically the mass deployment of Egyptians in the phalanx. As I noted last time, there had always been some ethnic Egyptians (legal “Persians”) in the phalanx, but the scale here is new. In addition, as we’ll see, the position of Ptolemy IV himself is odd, on the left wing matched directly against Antiochus III, rather than on his own right wing as would have been normal. But this is mostly a fairly normal setup and Polybius gives us a passably good description (better for Ptolemy than Antiochus, much like the battle itself).

We can start with the Seleucid Army and the tactical intent of the layout is immediately understandable. Antiochus III is modestly outnumbered – he is, after all, operating far from home at the southern end of the Levant (Raphia is modern-day Rafah at the southern end of Gaza), and so is more limited in the force he can bring. His best bet is to make his cavalry and elephant superiority count and that means a victory on one of the wings – the right wing being the standard choice. So Antiochus stacks up a 4,000 heavy cavalry hammer on his flank behind 60 elephants – Polybius doesn’t break down which cavalry, but we can assume that the 2,000 with Antiochus on the extreme right flank are probably the cavalry agema and the Companions, deployed around the king, supported by another 2,000 probably Macedonian heavy cavalry. He then uses his Greek mercenary infantry (probably thureophoroi or perhaps some are thorakitai) to connect that force to the phalanx, supported by his best light skirmish infantry: Cretans and a mix of tough hill folks from Cilicia and Caramania (S. Central Iran) and the Dahae (a steppe people from around the Caspian Sea).

His left wing, in turn, seems to be much lighter and mostly Iranian in character apart from the large detachment of Arab auxiliaries, with 2,000 more cavalry (perhaps lighter Persian-style cavalry?) holding the flank. This is a clearly weaker force, intended to stall on its wing while Antiochus wins to the battle on the right. And of course in the middle [is] the Seleucid phalanx, which was quite capable, but here is badly outnumbered both because of how full-out Ptolemy IV has gone in recruiting for his “Macedonian” phalanx and also because of the massive infusion of Egyptians.

But note the theory of victory Antiochus III has: he is going to initiate the battle on his right, while not advancing his left at all (so as to give them an easier time stalling), and hope to win decisively on the right before his left comes under strain. This is, at most, a modest alteration of Alexander-Battle.

Meanwhile, Ptolemy IV seems to have anticipated exactly this plan and is trying to counter it. He’s stacked his left rather than his right with his best troops, including his elite infantry (the agema and peltasts, who, while lighter, are more elite) and his best cavalry, supported by his best (and only) light infantry, the Cretans.1 Interestingly, Polybius notes that Echecrates, Ptolemy’s right-wing commander waits to see the outcome of the fight on the far side of the army (Polyb. 6.85.1) which I find odd and suggests to me Ptolemy still carried some hope of actually winning on the left (which was not to be). In any case, Echecrates, realizing that sure isn’t happening, assaults the Seleucid left.

I think the theory of victory for Ptolemy is somewhat unconventional: hold back Antiochus’ decisive initial cavalry attack and then win by dint of having more and heavier infantry. Indeed, once things on the Ptolemaic right wing go bad, Ptolemy moves to the center and pushes his phalanx forward to salvage the battle, and doing that in the chaos of battle suggests to me he always thought that the matter might be decided that way.

In the event, for those unfamiliar with the battle: Antiochus III’s right wing crumples the Ptolemaic left wing, but then begins pursuing them off of the battlefield (a mistake he will repeat at Magnesia in 190). On the other side, the Gauls and Thracians occupy the front face of the Seleucid force while the Greek and Mercenary cavalry get around the side of the Seleucid cavalry there and then the Seleucid left begins rolling up, with the Greek mercenary infantry hitting the Arab and Persian formations and beating them back. Finally, Ptolemy, having escaped the catastrophe on his left wing, shows up in the center and drives his phalanx forward, where it wins for what seem like obvious reasons against an isolated Seleucid phalanx it outnumbers almost 2-to-1.

But there are a few structural features I want to note here. First, flanking this army is really hard. On the one hand, these armies are massive and so simply getting around the side of them is going to be difficult (if they’re not anchored on rivers, mountains or other barriers, as they often are). Unlike a Total War game, the edge of the army isn’t a short 15-second gallop from the center, but likely to be something like a mile (or more!) away. Moreover, you have a lot of troops covering the flanks of the main phalanx. That results, in this case, in a situation where despite both wings having decisive actions, the two phalanxes seem to be largely intact when they finally meet (note that it isn’t necessarily that they’re slow; they seem to have been kept on “stand by” until Ptolemy shows up in the center and orders a charge). If your plan is to flank this army, you need to pick a flank and stack a ton of extra combat power there, and then find a way to hold the center long enough for it to matter.

Second, this army is actually quite resistive to Alexander-Battle: if you tried to run the Issus or Gaugamela playbook on one of these armies, you’d probably lose. Sure, placing Alexander’s Companion Cavalry between the Ptolemaic thureophoroi and Gallic mercenaries (about where he’d normally go) would have him slam into the Persian and Medean light infantry and probably break through. But that would be happening at the same time as Antiochus’ massive 4,000-horse, 60-elephant hammer demolished Ptolemaic-Alexander’s left flank and moments before the 2,000 cavalry left-wing struck Alexander himself in his flank as he advanced. The Ptolemaic army is actually an even worse problem, because its infantry wings are heavier, making that key initial cavalry breakthrough harder to achieve. Those chunky heavy-cavalry wings ensure that an effort to break through at the juncture of the center and the wing is foolhardy precisely because it leaves the breakthrough force with heavy cavalry to one side and heavy infantry to the other.

I know this is going to cause howls of pain and confusion, but I do not think Alexander could have reliably beaten either army deployed at Raphia; with a bit of luck, perhaps, but on the regular? No. Not only because he’d be badly outnumbered (Alexander’s army at Gaugamela is only 40,000 infantry and 7,000 cavalry) but because these armies were adapted to precisely the sort of army he’d have and the tactics he’d use. Even without the elephants (and elephants gave Alexander a hell of a time at the Hydaspes), these armies can match Alexander’s heavy infantry core punch-for-punch while having enough force to smash at least one of his flanks, probably quite quickly. Note that the Seleucid Army – the smaller one at Raphia – has almost exactly as much heavy infantry at Raphia as Alexander at Gaugamela (30,000 to 31,000), and close to as much cavalry (6,000 to 7,000), but of course also has a hundred and two elephants, another 5,000 more “medium” infantry and massive superiority in light infantry (27,000 to 9,000). Darius III may have had no good answer to the Macedonian phalanx, but Antiochus III has a Macedonian phalanx and then essentially an entire second Persian-style army besides (and his army at Magnesia is actually more powerful than his army at Raphia).

This is not a degraded form of Alexander’s army, but a pretty fearsome creature of its own, which supplements an Alexander-style core with larger amounts of light and medium troops (and elephants), without sacrificing much, if any, in terms of heavy infantry and cavalry. The tactics are modest adjustments to Alexander-Battle which adapt the military system for symmetrical engagements against peer armies. The Hellenistic Army is a hard nut to crack, which is why the kingdoms that used them were so successful during the third century, to the point that, until the Romans show up, just about the only thing which could beat a Hellenistic army was another Hellenistic army.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Phalanx’s Twilight, Legion’s Triumph, Part Ib: Subjects of the Successors”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2024-01-26.

1. You can tell how much those Cretans are valued, given that they get placed in key positions in both armies.

February 22, 2025

How the US Turned Iran Into a Dictatorship

Real Time History

Published 4 Oct 2024In 1953, Iran is at a crossroads. After decades of interference by foreign powers eager to exploit its oil reserves, the government decides it will throw them out and take control of the country’s wealth. But with the super powers’ Cold War paranoia and thirst for oil, it won’t be easy – especially once the CIA gets involved.

(more…)

February 17, 2025

QotD: Decisive factors in the Roman victory over the Seleucids

Zooming out even further, why Roman victory in the Roman-Seleucid War? I think there are a few clear factors here.

Ironically for a post covering land battles, the most important factor may be naval: Rome’s superior naval resources (and better naval allies), which gave the Romans an enormous operational advantage against Antiochus. In the initial phase, the Romans could get more troops to Greece than the king could, while further on, Roman naval supremacy allowed Roman armies to operate in Anatolia in force (while Antiochus, even had he won in Greece, had no hope of operating in Italy). Neutralizing Antiochus’ navy both opened up options for the Romans and closed down options for Antiochus, setting the conditions for Roman victory. It would have also neutered any Roman defeat. If Antiochus wins at Magnesia, he cannot then immediately go on the offensive, after all: he has merely bought perhaps a year or two of time to rebuild his navy and try to contest the Aegean again. Given the astounding naval mobilizations Rome had shown itself capable of in the third century, one cannot imagine Antiochus was likely to win that contest.

Meanwhile, the Romans had better allies, in part as a consequence of the Romans being better at getting allies. The Romans benefit substantially from allied Achaean, Pergamese and Rhodian ships and troops, as well as support from the now-humbled Philip V of Macedon and even supplies and auxiliaries from Numidia and Carthage. Alliance-management is a fairly consistent Roman strength and it shows here. It certainly seems to help that Roman protestations that they had little interest in a permanent presence in Greece seem to have been somewhat true; Rome won’t set up a permanent provincia in Macedonia until 146 (though the Romans do expect their influence to predominate before then). By contrast, Antiochus III, clearly bent on rebuilding Alexander’s empire, was a more obvious threat to the long-term independence and autonomy of Greek states like the Pergamum or Rhodes.

Finally, there is the remarkable Seleucid glass jaw. The Romans, after all, sustained a defeat very much like Magnesia against Hannibal in 216 (the Battle of Cannae) and kept fighting. By contrast, Antiochus is forced into a humiliating peace after Magnesia, in which he cedes all of Anatolia, gives up any kind of navy and is forced to pay a crippling financial indemnity which will fatally undermine the reign of his successor and son Seleucus IV (leading to his assassination in 175, leading to yet further Seleucid weakness). Part of this glass jaw may have been political: after Magnesia, Antiochus’ own aristocrats seem pretty well done with their king’s adventurism against Rome.

But at the same time, some of it was clearly military. Antiochus didn’t have a second army to fall back on and Magnesia represented essentially a peak “all-call” Seleucid mobilization. A similar defeat at Raphia had forced a similarly unfavorable peace earlier in his reign, after all. Part of the problem, I would argue, is that the Seleucids needed their army for more than just war: they needed it to enforce taxation and tribute on their own recalcitrant subjects. As a result, no Seleucid king could afford to “go for broke” the way the Roman Republic could, nor could the Seleucids ever fully mobilize the massive population of their realm. The very nature of the Hellenistic kingdom’s ethnic hierarchy made fully tapping the potential resources of the kingdom impossible.

As a result, while Antiochus III was not an incompetent general, he ruled a deceptively weak giant. Massive revenues were offset by equally massive security obligations and the Seleucids seem to have been perenially cash strapped (with a nasty habit of looting temples to make up for it). The very nature of the Seleucid Empire – like the Ptolemaic one – as an ethnic empire where Macedonians ruled and non-Macedonians were ruled kept Antiochus from being able to fully mobilize his subjects. It may also explain why so many of those light infantry auxiliaries seem to have run off without much of a fight. Eumenes and his Pergamese troops fought for their independence, the Romans for the greater glory of Rome and the socii for their own status and loot within the Roman system, but what could Antiochus offer a subjected Carian or Cilician except a paycheck and a future of continued subjugation? That’s not much to die for.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Phalanx’s Twilight, Legion’s Triumph, Part IVb: Antiochus III”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2024-04-05.

February 10, 2025

QotD: The Roman Republic versus the heirs of Alexander the Great

Last time, we finished our look at the third-century successes of the phalanx with the career of Pyrrhus of Epirus, concluding that even when handled very well with a very capable body of troops, Hellenistic armies struggled to achieve the kind of decisive victories they needed against the Romans to achieve strategic objectives. Instead, Pyrrhus was able to achieve a set of indecisive victories (and a draw), which was simply not anywhere close to enough in view of the tremendous strategic depth of Rome.

Well, I hope you got your fill of Hellenistic armies winning battles because it is all downhill from here (even when we’re fighting uphill). For the first half of the second century, from 200 to 168, the Romans achieve an astounding series of lopsided victories against both (Antigonid) Macedonian and Seleucid Hellenistic armies, while simultaneously reducing several other major players (Pergamon, Egypt) to client states. And unlike Pyrrhus, the Romans are in a position to “convert” on each victory, successfully achieving their strategic objectives. It was this string of victories, so shocking in the Greek world, that prompted Polybius to write his own history, covering the period from 264 to 146 to try to explain what the heck happened (much of that history is lost, but Polybius opens by suggesting that anyone paying attention to the First Punic War (264-241) ought to have seen this coming).

That said, this series of victories is complex. Of the five major engagements (The River Aous, Cynoscephalae, Thermopylae, Magnesia, and Pydna) Rome commandingly wins all of them, but each battle is strange in its own way. So we’re going to look at each battle and also take a chance to lay out a bit of the broader campaigns, asking at each stage why does Rome win here? Both in the tactical sense (why do they win the battle) and also in the strategic sense (why do they win the war).

We’re going to start with the war that brought Rome truly into the political battle royale of the Eastern Mediterranean, the Second Macedonian War (200-196). Rome was acting, in essence, as an interloper in long-running conflicts between the various successor dynasties of Alexander the Great as well as smaller Greek states caught in the middle of these larger brawling empires. Briefly, the major players are the Ptolemaic Dynasty, in Egypt (the richest state), the Seleucid Dynasty out of Syria and Mesopotamia (the largest state) and the Antigonid Kingdom in Macedonia (the smallest and weakest state, but punching above its weight with the best man-for-man army). The minor but significant players are the Attalid dynasty in Pergamon, a mid-sized Hellenistic power trapped between the ambitions of the big players, two broad alliances of Greek poleis in the Greek mainland the Aetolian and Achaean Leagues, and finally a few freewheeling poleis, notably Athens and Rhodes. The large states are trying to dominate the system, the small states trying to retain their independence and everyone is about to get rolled by the Romans.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Phalanx’s Twilight, Legion’s Triumph, Part IVa: Philip V”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2024-03-15.

February 2, 2025

Hierapolis: a city encased in stone

Scenic Routes to the Past

Published 18 Oct 2024Hierapolis — modern Pamukkale, Turkey — was built over hot springs. During the Middle Ages, these encased much of the city in gleaming travertine.

See my upcoming trips to Turkey and other historical destinations: https://trovatrip.com/host/profiles/g…

January 15, 2025

Desert Storm: The Gulf War 1990-1991

Real Time History

Published 6 Sept 2024When Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait in the summer of 1990, he didn’t anticipate a massive international backslash and unanimous Security Council response. Soon a broad military Coalition under leadership of the United States assembled and kicked the Iraqi Army out of Kuwait. In the aftermath several Iraqi groups rose up against Saddam but the Coalition didn’t support a regime change.

CHAPTERS:

00:00 Intro

00:29 Saddam Hussein Victorious (but Broke)

03:49 Iraqi Invasion of Kuwait

06:02 The Coalition Against Iraq Forms

08:37 Operation Desert Shield

10:55 Operation Desert Storm

20:26 Iraqi Highway of Death

21:39 Iraqi Uprisings

(more…)