David Friedman has some timely tips on how you might go about determining the truth of an assertion offered in the legacy media or online source of undetermined trustworthiness:

Following up the claim you come across an article, perhaps even a book, which does indeed support that claim. Should you believe it?

The short answer for all of those examples, some of them claims I agree with, is that you should not. As I think I have demonstrated in past posts, claimed proofs of contentious issues are quite often wrong, biased, even fraudulent.

More examples from previous posts, here or on my old blog:

An estimate of the cost of a ton of carbon dioxide calculated with about half the total depending on the implicit assumption of no progress in medicine for the next three centuries.

A factbook on state and local finance that deliberately omitted the most important relevant fact that readers were unlikely to know.

A textbook, in its third edition, with multiple provably false claims.

The important question is how to tell. There are three answers:

1. Read the book or article carefully, check at least some of its claims — easier now that the Internet provides you with a vast searchable library accessible from your desktop — and evaluate its argument for yourself. Doing this is costly in time and effort and requires skills you may not have; depending on the particular issue that might include near-professional expertise in statistics, history, physics, economics, or any of a variety of other fields. I have taught elementary statistics at various points in my career, both in an economics department and a law school, but gave up on a controversy of considerable interest to me (concealed carry) when the statistical arguments got above the level I could readily follow.

2. Find one or more competent critiques of the argument and see if you find them convincing. This is the previous answer on easy mode. You still have to think things through but you don’t have to search out mistakes in the argument for yourself because the critic will point you at them, with luck offer evidence.

There are three possible conclusions that that exercise may support: that the argument is wrong. that it might be wrong, that it is probably right. The way you reach the last conclusion is from the incompetence or dishonesty of the critique; I am thinking of a real case.

John Boswell, a gay historian at Yale, argued that both the scriptures and early Christianity, unlike modern Christian critics of homosexual sex, treated it as no worse than other forms of non-marital intercourse. What convinced me that Boswell had a reasonable case was reading an attack on him by a prominent opponent which badly misrepresented the contents of the book I had just read. People who have good arguments do not need bad ones.

Of course, there might be other critics with better arguments.

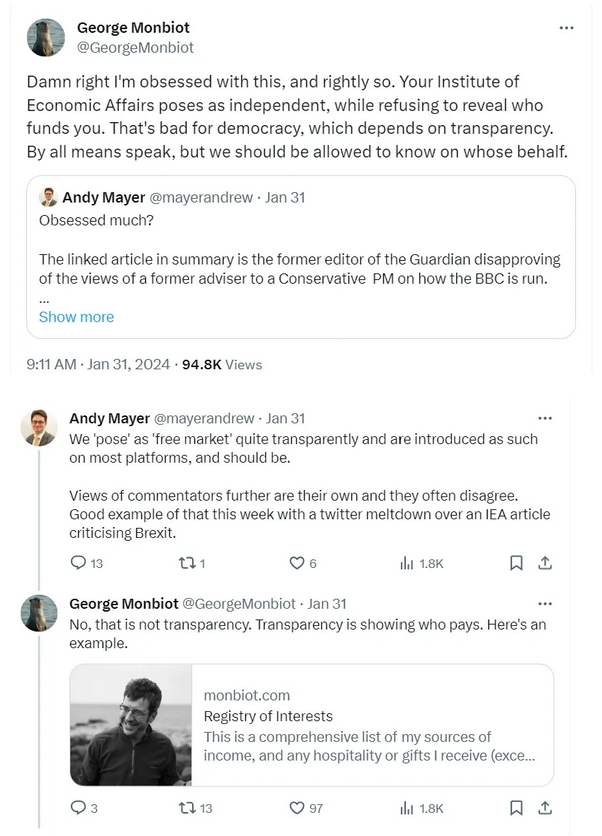

An entertaining version of this approach is to find an online conversation with intelligent people covering a wide range of views and follow discussions of whatever issues you are interested in. With luck all of the good arguments for both sides will get made and you can decide for yourself whether one side, the other, or neither is convincing. Forty years ago I could do it in the sf groups on Usenet, which contained lots of smart people who liked to argue. Five years ago I could do it in the comment threads of Slate Star Codex. Currently Data Secrets Lox works for a few controversies but the range of views represented on it is too limited to provide a fair view of most.

The comment threads of this blog are at present too thin for the purpose, with between one and two orders of magnitude fewer comments than the SSC average used to be, but perhaps in another few years …

3. Recognize that you don’t know whether the claim is true and have no practical way of finding out, at least no way that costs less in time and effort than it is worth. This is the least popular answer but probably the most often correct.