Unlike private capital, foreign “aid” enters a country not because conditions there favor economic growth but because that country is poor — because that country lacks institutions and policies necessary for growth. And the more miserable its citizens’ lives, the more foreign “aid” its government receives.

Can you imagine a more perverse incentive? The poorer and more wretched are a nation’s people, the more likely celebrities such as Bono will convince Westerners and their governments to take pity on that country and to send large sums of money to its government. And because that country’s citizens are poor largely because their government is corrupt and tyrannical, the money paid in “aid” to that government will do nothing to help that country develop economically.

The cycle truly is vicious. Aid money naively paid by Westerners to alleviate Third-World poverty is stolen or misspent by the thugs who control the governments there. Nothing is done to foster the rule of law and private property rights that alone are the foundation for widespread prosperity. The people remain mired in ghastly poverty, their awful plight further attracting the attention and sympathy of Western celebrities, who use their star attraction and media savvy to shame politicians in the developed world into doling out yet more money to the thugs wielding power in the (pathetically misnamed) “developing world”.

If I could figure out a way to measure the long-term consequences of this new round of debt relief — a way that is so clear and objective that even the most biased party could not quibble with it — I would offer to bet a substantial sum of money that years from now this debt relief will be found to have done absolutely no good for the average citizens of the developing world.

It’s a bet I would surely — and sadly — win.

Don Boudreaux, “Faulty Band-Aid”, Pittsburgh Tribune-Review, 2005-06-18.

August 9, 2024

QotD: Celebrity fund-raising for foreign aid

July 22, 2024

QotD: Post-apartheid South Africa

There were two things that finally caused the dam to break and muted criticism of the South African regime to start appearing in the international press: the first was the situation in Zimbabwe. Like South Africa, Zimbabwe had recently ended decades of white minority rule, but in Zimbabwe things went way more wrong, way more quickly. Robert Mugabe, the incumbent president of Zimbabwe, was running in a contested election, and decided to ensure his victory with a campaign of mass murder and torture which in turn triggered a famine and a refugee crisis.

All of this brought tons of international condemnation onto the Zimbabwean regime, and a lot of countries looking for ways to pressure it to stop the atrocities. The glaring exception was Mbeki’s South Africa, which staunchly defended Zimbabwe for years as the killing and the starvation just kept ratcheting up. It’s unclear why they did this, beyond the ANC and ZANU-PF (the Zimbabwean ruling party) having a certain ideological and familial kinship, both being post-colonialist revolutionary parties that had overthrown white minority rule. But whatever the reason, this was the straw that finally caused Western politicians and celebrities to wake up a little bit and realize that South Africa was now ruled by thugs.

The second, even more catastrophic event that caused the South African government to lose the sheen of respectability was the AIDS epidemic and their response to it. The story of how Mbeki buried his head in the sand, embraced quack theories on the causes of AIDS, and condemned hundreds of thousands of people to avoidable deaths is well known at this point, but Johnson’s book is full of grimly hysterical details that turn the whole story into the darkest comedy you’ve ever seen.

For example: I had no idea that Mbeki was so ahead of his time in outsourcing his opinions to schizopoasters on the internet. According to his confidantes, at the height of the crisis the president was frequently staying up all night interacting pseudonymously with other cranks on conspiracy-minded forums (an important cautionary tale for all those … umm … friends of mine who enjoy dabbling in a conspiracy forum or two). These views were then laundered through a succession of bumbling and imbecilic health ministers such as Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma or Mantombazana Tshabalala-Msimang who gave surreal press conferences extolling the healing powers of “Africanist” remedies such as potions made from garlic, beetroot, and potato.

Actually, the potions were a step up in some respects, the original recommendation from the South African government was that AIDS patients should consume “Virodene”, a toxic industrial solvent marketed by a husband-wife con-artist duo named Olga and Siegfried Visser. Later documents came to light revealing large and inexplicable money transfers between the Vissers and Tshabalala-Msiming. The Vissers then established a secret lab in Tanzania where they experimented on unsuspecting human subjects, engaged in bizarre sexual antics, and performed cryonics experiments on corpses. Despite this busy schedule, they also produced a constant stream of confidential memos on AIDS policy that were avidly consumed by Mbeki.

The horror of it all is that by this point there were very good drugs that could massively cut the risk of mother-child HIV transmission and somewhat reduced the odds of contracting the virus after a traumatic sexual encounter. There were a lot of traumatic sexual encounters. A contemporaneous survey found that around 60 percent of South Africans believed that forcing sex on somebody was not necessarily violence, and a common “Africanist” belief was that sex with a virgin could cure AIDS, all of which led to extreme levels of child rape. The government then did everything in its power to prevent the victims of these rapes from accessing drugs that could stave off a deadly disease. At first the excuse was that they were too expensive, then when the drug companies called that bluff and offered the drugs for free, it became that they caused “mutations”.

John Psmith, “REVIEW: South Africa’s Brave New World, by R.W. Johnson”, Mr. and Mrs. Psmith’s Bookshelf, 2023-03-20.

July 13, 2024

The real story of Henry Hook, VC – Zulu

The History Chap

Published Nov 23, 2023Henry Hook, VC, 1850-1905. Zulu — the Battle of Rorke’s Drift.

Henry Hook was one of 11 defenders at the mission station at Rorke’s Drift (battle of Rorke’s Drift, Anglo-Zulu War 1879) who were awarded the Victoria Cross. Controversially, his character was misrepresented in the 1963 film Zulu. His character, played by James Booth (1927-2005), was depicted as an insubordinate barrack-room lawyer, a drunk and a malingerer. This was far from the truth.

Hook was actually a model soldier, who was teetotal, and who would serve as a regular and volunteer for over 40 years. His family were upset by the film, although contrary to popular stories, there is no evidence that Henry Hook’s daughters walked out of the [movie’s] premiere.

Nevertheless, in this video I aim to share his real story. Not just of his service in the army (and at Rorke’s Drift) but of a humble man from Gloucestershire, who returned home to find his wife had run off with another man, who found love for a second time and who worked in the British Museum.

Where is Henry Hook buried? Henry Hook’s grave can be found at St. Andrew’s church in the hamlet of Churcham, Gloucestershire. it is about five miles west of Gloucester.

0:00 Introduction

1:26 Early Life

3:10 Rorke’s Drift

3:56 Zulu

5:00 Defending The Hospital

7:45 Assegai wound

9:47 Making Tea

10:23 Victoria Cross

11:07 After Rorke’s Drift

13:11 Failing Health

15:10 The History Chap

(more…)

July 5, 2024

QotD: South Africa after Apartheid

Now, what has replaced this abhorrent socio-political system [apartheid] is not good, at all; indeed, what has since happened in South Africa is typical of most African countries: massive corruption, bureaucratic inertia, inefficiency and incompetence, and a level of violence which makes Chicago’s South Side akin to a holiday resort. (For those who wish to know the attribution for much of the above, I recommend reading the chapter entitled “Caliban’s Kingdoms” in Paul Johnson’s Modern Times.) Where South Africa differs from other African countries is twofold: where in the rest of Africa the preponderance of violence and oppression was Black on Black — and therefore ignored by the West — apartheid was a system of White on Black oppression (and therefore more noticeable to Western eyes). The second difference is that apartheid exacerbated the virulence of the “grievance” culture which demands reparations (financial and otherwise) for the iniquities of apartheid. This continues to unfold, to where the homicide rate for White farmers — part of the taking of farmland from Whites — is one of the highest in the world, and the capture and conviction rates for the Black murderers among the lowest — a simple inversion of the apartheid era.

Speaking with hindsight, however, it would be charitable to suggest […] that apartheid was “simply a logical adaptation to the presence of a population that simply cannot support or sustain a First World standard of living, done by people who very much valued the First World society they had created”. While that statement is undoubtedly true, up to a point, and it could be argued that apartheid was a pragmatic solution to the chaos evident throughout the rest of Africa, it cannot be used as an excuse. Indeed, such a labeling would give, and has given rise to the notion that First World systems are inherently unjust, and a different label “colonialism” — which would include apartheid — can be applied to the entirety of Western Civilization.

The fact of the matter is that when it comes to Africa, there is no good way. First World — i.e. Western European — principles only work in a socio-political milieu in which principles such as the rule of law, free trade, non-violent transfer of political power and the Enlightenment are both understood and respected. They aren’t, anywhere in Africa, except where such adherence can be worked to temporary local advantage. Remember, in the African mindset there is no long-term thinking or consideration of consequence — which is why, for example, since White government (not just South African) has disappeared in Africa, the infrastructure continues to crumble and fail because of a systemic and one might say almost genetic indifference to its maintenance. When a government is faced with a population of which 90% is living in dire poverty and in imminent danger of starvation, that government must try to address that first, or face the prospect of violent revolution. It’s not an excusable policy, but it is understandable.

That said, there is no gain in rethinking apartheid’s malevolence […] because apartheid was never going to last anyway, and its malevolence was bound to engender a similar counter-malevolence once it disappeared. Which is the main point to my thinking on Africa: nothing works. Africa is simply a train-smash continent, where good intentions come to nought, where successful systems and ideas fail eventually, and where unsuccessful systems (e.g. Marxism) also fail, just fail more quickly.

Kim du Toit, “Tough Question, Simple Answer”, Splendid Isolation, 2019-12-05.

June 22, 2024

The End of Everything

In First Things, Francis X. Maier reviews Victor Davis Hanson’s recent work The End of Everything: How Wars Descend into Annihilation:

A senior fellow in military history and classics at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution, Hanson is a specialist on the human dimension and costs of war. His focus in The End of Everything is, as usual, on the past; specifically, the destruction of four great civilizations: ancient Thebes, Carthage, Constantinople, and the Aztec Empire. In each case, an otherwise enduring civilization was not merely conquered, but “annihilated” — in other words, completely erased and replaced. How such catastrophes could happen is the substance of Hanson’s book. And the lessons therein are worth noting.

In every case, the defeated suffered from fatal delusions. Each civilization overestimated its own strength or skill; each misread the willingness of allies to support it; and each underestimated the determination, strength, and ferocity of its enemy.

Thebes had a superb military heritage, but the Thebans’ tactics were outdated and their leadership no match for Macedon’s Alexander the Great. The city was razed and its surviving population scattered. Carthage — a thriving commercial center of 500,000 even after two military defeats by Rome — misread the greed, jealousy, and hatred of Rome, and Roman willingness to violate its own favorable treaty terms to extinguish its former enemy. The long Roman siege of the Third Punic War saw the killing or starvation of 450,000 Carthaginians, the survivors sold into slavery, the city leveled, and the land rendered uninhabitable for a century.

The Byzantine Empire, Rome’s successor in the East, survived for a millennium on superior military technology, genius diplomacy, impregnable fortifications, and confidence in the protection of heaven. By 1453, a shrunken and sclerotic Byzantine state could rely on none of these advantages, nor on any real help from the Christian West. But it nonetheless clung to a belief in the mantle of heaven and its own ability to withstand a determined Ottoman siege. The result was not merely defeat, but the erasure of any significant Greek and Christian presence in Constantinople. As for the Aztecs, they fatally misread Spanish intentions, ruthlessness, and duplicity, as well as the hatred of their conquered “allies” who switched sides and fought alongside the conquistadors.

The industrial-scale nature of human sacrifice and sacred cannibalism practiced by the Aztecs — more than 20,000 captives were ritually butchered each year — horrified the Spanish. It reinforced their fury and worked to justify their own ferocious violence, just as the Carthaginian practice of infant sacrifice had enraged the Romans. In the end, despite the seemingly massive strength of Aztec armies, a small group of Spanish adventurers utterly destroyed Tenochtitlán, the beautiful and architecturally elaborate Aztec capital, and wiped out an entire culture.

History never repeats itself, but patterns of human thought and behavior repeat themselves all the time. We humans are capable of astonishing acts of virtue, unselfish service, and heroism. We’re also capable of obscene, unimaginable violence. Anyone doubting the latter need only check the record of the last century. Or last year’s October 7 savagery, courtesy of Hamas.

The takeaway from Hanson’s book might be summarized in passages like this one:

Modern civilization faces a toxic paradox. The more that technologically advanced mankind develops the ability to wipe out wartime enemies, the more it develops a postmodern conceit that total war is an obsolete exercise, [assuming, mistakenly] that disagreements among civilized people will always be arbitrated by the cooler, more sophisticated, and more diplomatically minded. The same hubris that posits that complex tools of mass destruction can be created but never used, also fuels the fatal vanity that war itself is an anachronism and no longer an existential concern—at least in comparison to the supposedly greater threats of naturally occurring pandemics, meteoric impacts, man-made climate change, or overpopulation.

Or this one:

The gullibility, and indeed ignorance, of contemporary governments and leaders about the intent, hatred, ruthlessness, and capability of their enemies are not surprising. The retreat to comfortable nonchalance and credulousness, often the cargo of affluence and leisure, is predictable given unchanging human nature, despite the pretensions of a postmodern technologically advanced global village.

I suppose the lesson is this: There’s nothing sacred about the Pax Americana. Nothing guarantees its survival, legitimacy, comforts, power, or wealth. A sardonic observer like the Roman poet Juvenal — were he alive — might even observe that today’s America seems less like the “city on a hill” of Scripture, and more like a Carthaginian tophet, or the ritual site of child sacrifice. Of course, that would be unfair. A biblical leaven remains in the American experiment, and many good people still believe in its best ideals.

June 19, 2024

Toronto “atones for slavery” by renaming Yonge-Dundas Square. They chose … poorly.

In the never-ending quest for moral superiority, the City of Toronto decided to rename a downtown landmark — Yonge-Dundas Square — after allegations were made that British Home Secretary Henry Dundas was against the abolition of slavery in the 1790s. (In fact, it was partly his efforts to mediate between the abolitionists and their opponents that actually got the first anti-slavery bill through Parliament, but who cares about his actual work when we can issue blanket condemnations hundreds of years later?)

In a twist worthy of the Babylon Bee, it turns out that the new and improved name proposed has a much more direct connection with slavery:

The Yonge-Dundas Square sign on the southeast corner of the intersection in downtown Toronto.

Detail of an image from Google Street View.

There is a lot wrong both with the name that Toronto city council chose to replace Yonge-Dundas Square and the burden that the name change will place on taxpayers.

Originally budgeted at $335,000, the new estimate is $860,000 — and who is to say it won’t go higher? That would be a lot of money even for a desirable name, but the name the city chose, Sankofa Square, is problematic.

The term is Ghanaian and means “learning from the past.” But while it is intended to replace the name of Henry Dundas, who some blame for delaying the abolition of slavery in the British Empire, the term “Sankofa” has its own connection to the slave trade.

Slavery was rife throughout Africa, and much of the world, for centuries past, but Ghana’s version included the execution of the slaves of chiefs who died, so that they could serve him in the afterlife. […]

The basic fact, ignored by Toronto’s mayor and city councillors, is that the Gold Coast, the earlier name for Ghana, was a notorious slave society. Leading Ghanaians were prominent in the slave trade and were themselves slave owners. For years after slavery was abolished elsewhere, they fought its abolition in Ghana. It wasn’t until 1874 that the slave trade in Ghana was abolished — nearly a century after Britain.

Compare Ghana’s record with that of Ontario, where a process of gradual abolition was started in 1793, 81 years before Ghana. That, notably, was thanks to the efforts of Upper Canada’s first lieutenant governor, John Graves Simcoe, an appointee of Henry Dundas, no less.

So Dundas was not only instrumental in getting slavery abolished in Scotland, acting as a lawyer in the appeal of a case dealing with a runaway slave, he also sent a dedicated abolitionist to Upper Canada to take the top post. He deserves a better square than Yonge-Dundas!

June 10, 2024

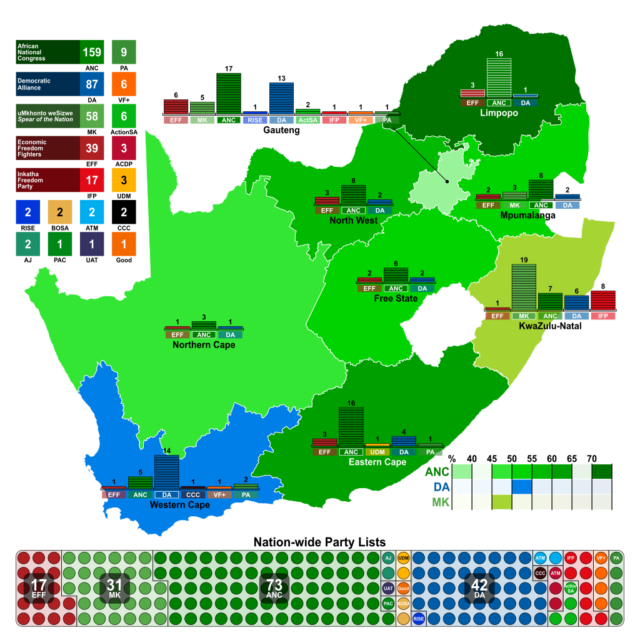

South Africa’s “Rainbow Nation” falters

Niccolo Soldo’s weekly roundup included a lengthy section on the recent election results in South Africa and what they might mean for the nation’s short- and medium-term stability:

Being a teen, the issue of South African Apartheid didn’t really fit all that well within the overarching Cold War paradigm. Unlike most other global issues, this one didn’t break down cleanly between the “freedom-loving West” and the “dictatorial, oppressive communist bloc”, as the push to dismantle the regime came from western liberals who were in agreement with the reds.

This slight bit of complexity did not faze most people, as Apartheid was seen as a relic of an older world, one to be consigned to the proverbial dustbin of history. It’s elimination did fit well enough into the Post-Berlin Wall world, one in which freedom and democracy were to reign supreme. This was more than enough reason for almost all people to cheer the release of Nelson Mandela and applaud South Africa’s embrace of western liberal democracy.

In the early 1990s, men once again dared to flirt with utopian ideas, and South Africa’s “Rainbow Nation” was to be its centrepiece: out with authoritarianism, racism, ethnocentrism, etc., and in with multiracialism, multiethnicity, democracy and individual liberty. We could all leave the past where it belonged (in the past) and live in peace and harmony, as democracy would defend it, secure it, and preserve it. South Africa would lead the way, and would in fact teach us westerners how it is to be done.

Oddly enough, South Africa quickly fell off of the radar of mainstream media in the West when it failed to live up to these lofty goals. Rather than living up to the hype of being the “Rainbow Nation”, it instead was quickly mired in the politics of corruption and race, showing itself to be all too human, just like the rest of us. South Africa had failed to immediately resolve its inherent internal tensions, whether they be racial, economic, ethnic, or ideological, and by extension it had failed to deliver its promise to western liberals. “Out of sight, out of mind” became the best practice, replacing the utopianism of the first half of the 1990s.

Granted, a lot of grace was given to South Africa by western media so long as Nelson Mandela remained in office (and even after that), but the failures were plainly evident to see: an explosion in crime and in corruption were its most obvious characteristics, ones that could not be brushed under the carpet. The African National Congress (ANC), the party that would deliver the promise of the Rainbow Nation, was instead shown to be little more than a powerful engine of corruption and patronage. Luckily for the ANC, it was fueled in large part by the legacy of Mandela and the goodwill that he had accumulated over the years while he sat in prison.

The post-Mandela era has not been kind to the ANC (nor to South Africa as a whole), as the party could no longer hide behind his fading legacy, and could no longer cash in on the goodwill that came from it. It could “put up”, and would it not “shut up”. The ANC over time became a lumbering beast, too big to slay, but too slow to destroy its opposition when compared to its nimble youth.

What has the party delivered in its three decades of power? It did help dismantle Apartheid, but it did not deliver economic prosperity and opportunity to all. Instead, it simply swapped out elites where it could, preferring to keep the new ones in house. An inability to tame crime and to keep the national power grid running has turned the country into a bit of a joke, especially when it is lumped into the BRICS group alongside Brazil, Russia, India, and China. Despite its abundance of natural wealth, South Africa has been economically mismanaged.

South Africa is an important country to watch for the simple reason that there is so much tinder lying around, ready to be set ablaze. Luckily for South Africans, dire projections of widespread civil strife have not come to pass. Unluckily for South Africans, their national trajectory is headed in the wrong direction. Last week’s national elections saw the ANC lose their parliamentary majority for the first time ever, and the only way to read the results is to conclude that no matter how one may feel about this very corrupt party, it is an ominous sign.

June 1, 2024

I plead the Pith: a History of the Pith Helmet

HatHistorian

Published Jun 1, 2022A symbol of exploration, tropical adventure, and colonialism, the pith helmet has had a long history since its origins as the salakot, a Philippine sun hat. Through many iterations, it had become one of the most famous hats out there, a powerful part of popular imagination.

The helmets I wear in this video come respectively from a gift from a family friend (so I don’t know where it was bought, https://www.historicalemporium.com/, and Amazon.com. The red tunic comes from thehistorybunker.co.uk

Title sequence designed by Alexandre Mahler

am.design@live.comThis video was done for entertainment and educational purposes. No copyright infringement of any sort was intended.

May 21, 2024

Idi Amin would have loved MMT

Jon Miltimore talks about the economic disaster of Idi Amin’s Uganda after Amin and his predecessor decided to nationalize most big businesses in the country and then to print money to cover the government shortfalls in revenue that resulted:

Ugandan dictator Idi Amin at the United Nations, October 1975.

Detail of a photo by Bernard Gotfryd via Wikimedia Commons.

Idi Amin (1923-2003) was one of the most ruthless and oppressive dictators of the 20th Century.

Many will remember Amin from the 2006 movie The Last King of Scotland, a historical drama that netted Forest Whitaker an Academy Award for Best Actor for his depiction of the Ugandan president.

While Western media often mocked Amin, who ruled Uganda from 1971 to 1979, as a self-aggrandizing buffoon, they tended to overlook the atrocities he inflicted on his people. He murdered an estimated 300,000 Ugandans, many of them in brutal fashion. One such victim is believed to be Amin’s fourth wife, Kay, whose body was found decapitated and dismembered in a car trunk in 1974, shortly after the couple divorced.

While historians and journalists have tended to focus on Amin’s dismal record on human rights, his economic policies are atrocities in their own right and also deserve attention.

A Brief History of Uganda

Uganda, a landlocked country in the eastern part of Central Africa, received its independence from the United Kingdom on Oct. 9, 1962 (though Queen Elizabeth remained the official head of state). The nation’s earliest years were turbulent.

Uganda was ruled by Dr. Apollo Milton Obote — first as prime minister and then as president — until January 1971, when an upstart general who had served in the British Colonial Army, Idi Amin Dada Oumee, seized control and set himself up as a dictator. (The coup was launched before Amin, a lavish spender, could be arrested for misappropriation of army funds.)

Among Amin’s first moves as dictator was to complete the nationalization of businesses that had begun under his predecessor Obote, who had announced an order allowing the state to assume a 60 percent stake in the nation’s top industries and banks. Obote’s announcement, The New York Times reported at the time, had resulted in a surge of capital flight and “brought new investment to a virtual stand still”. But instead of reversing the order, Amin cemented and expanded it, announcing he was taking a 49 percent stake in 11 additional companies.

Amin was just getting started, however. The following year he issued an order expelling some 50,000 Indians with British passports from the country, which had a devastating economic impact on the country.

“‘These Ugandan ‘Asians’ were entrepreneurial, talented and hard-working people, skilled in business, and they formed the backbone of the economy,” Madsen Pirie, President of the UK’s Adam Smith Institute, wrote in an article on Amin’s expulsion order. “However, Idi Amin favoured people from his own ethnic background, and arbitrarily expelled them anyway, giving their property and businesses to his cronies, who promptly ran them into the ground through incompetence and mismanagement.”

Even as he was nationalizing private industry and expelling Ugandan Asians, Amin was busy rapidly expanding the country’s public sector.

The Ugandan economy was soon in shambles. Amin’s financial advisors were naturally frightened to share this news with Amin, but in his book Talk of the Devil: Encounters With Seven Dictators, journalist Riccardo Orizio says one finance minister did just that, informing Amin “the government coffers were empty”.

The response from Amin is telling.

“Why [do] you ministers always come nagging to President Amin?” he said. “You are stupid. If we have no money, the solution is very simple: you should print more money.”

Tribalism

Theophilus Chilton pulls up an older essay from the vault, discussing tribalism, how it likely arose, and examples of cultures that relapsed into tribalism for various reasons:

In this post, I’d like to address the phenomenon of tribalism. There can be two general definitions of this term. The first is attitudinal – it refers to the possession by a group of people of a strong ethnic and cultural identity, one which pervades every level and facet of their society, and which serves to separate (often in a hostile sense) the group’s understanding of itself apart from its neighbours. The second definition is more technical and anthropological, referring to a group of people organised along kinship lines and possessing what would generally be referred to as a “primitive” governmental form centered around a chieftain and body of elders who are often thought to be imbued with supernatural authority and prestige (mana or some similar concept). The first definition, of course, is nearly always displayed by the second. It is this second definition which I would like to deal with, however.

Specifically, I’d like to explore the question of how tribalism relates to the collapse of widely spread cultures when they are placed under extreme stresses.

There is always the temptation to view historical and pre-historical (i.e., before written records were available) people-groups which were organised along tribal lines as “primitives” or even “stupid”. This is not necessarily the case, and in many instances is certainly not true. However, tribalism is not a truly optimal or even “natural” form of social organisation, and I believe is forced onto people-groups more out of necessity than anything else.

Before exploring the whys of tribalism’s existence, let’s first note what I believe can be stated as a general truism – Mankind is a social creature who naturally desires to organise himself along communal lines. This is why cities, cultures, civilisations even exist in the first place. Early in the history of Western science, Aristotle expressed this sentiment in his oft-quoted statement that “Man is by nature a political animal” (ὁ ἄνθρωπος φύσει πολιτικὸν ζῷον). This aphorism is usually misunderstood, unfortunately, due to the failure of many to take its cultural context into account. Aristotle was not saying that mankind’s nature is to sit around reading about politicians in the newspaper. He was not talking about “politics” in some sort of demotic or operational sense. Rather, “political” means “of the polis” [” rel=”noopener” target=”_blank”>link]. The polis, in archaic and classical Greece, was more than just a city-state – it was the very sum of Greek communal existence. Foreigners without poleis were not merely barbarians, they were something less than human beings, they lacked a crucial element of communal existence that made man – capable of speech and reason – different from the animals and able to govern himself rationally. “Political” did not mean “elections” or “scandals”, as it does with us today. Instead, it meant “capable of living with other human beings as a rational creature”. It meant civilisation itself. Tribalism, while perhaps incorrectly called “primitive”, nevertheless is “underdeveloped”. It is in the nature of man to organise himself socially, and even among early and technologically backwards peoples, this organisation was quite often more complex than tribal forms. While modern cities may be populated by socially atomised shells of men, the classical view of the city was that it was vital to genuine humanity.

My point in all of this is that I don’t believe that tribal organisation is a “natural” endpoint for humanity, socially speaking. The reason tribes are tribes is not because they are all too stupid to be capable of anything else, nor because they have achieved an organisation that truly satisfies the human spirit and nature. As the saying goes, “The only morality is civilisation”. The direction of man’s communal association with man is toward more complex forms of social and governing interactions which satisfy man’s inner desire for sociability.

So why are tribal peoples … tribal? My theory is that tribalism arises neither from stupidity or satisfaction, but as a result of either environmental factors such as geography, habitability, etc. which inhibit complexification of social organisation, or else as a result of civilisation-destroying catastrophes which corrode and destroy central authority and the institutions necessary to maintain socially complex systems.

The first – environmental factors – would most likely be useful for explaining why cultures existing in more extreme biomes persist in a tribal state. For example, the Arctic regions inhabited by the Inuit would militate against building complexity into their native (i.e. pre-contact with modern Europeans) societies. The first great civilisations of the river valleys – Egypt, Mesopotamia, the Indus valley, and China – all began because of the organisation needed to construct and administer large scale irrigation projects for agriculture. Yet, the weather in the Arctic precludes any sort of agriculture, as well as many other activities associated with high civilisation such as monumental architecture and large scale trade. The Inuit remained tribal hunter-gatherers not because they were inherently incapable of high culture, but because their surroundings inhibited them from it. Likewise, the many tribal groups in the Rub’ al-Khali (the Empty Quarter of the Arabian peninsula) were more or less locked into a semi-nomadic transhumant existence by their environment, even as the racially and linguistically quite similar peoples of Yemen and the Hadramaut were developing complex agricultural and commercial cultures along the wadis.

However, I believe that the more common reason for tribalism in history is that of catastrophes – of various types, some fast-acting and others much slower – which essentially “turned the world upside down” for previous high civilisations which were affected by them. I believe that there are many examples of this which can be seen, or at least inferred, from historical study. I’ll detail five of them below.

The first is an example which would formerly have been considered to fall into the category of tribes remaining tribal because of geographical factors, but which recent archaeological evidence suggests is not the case. This would be the tribes (or at least some of them) of the Amazon jungles, especially the Mato Grosso region of western Brazil. Long considered to be one of the most primitive regions on the planet, one could easily make the argument that these tribes were such because of the extreme conditions found in the South American jungles. While lush and verdant, these jungles are really rather inhospitable from the standpoint of human habitability – the jungle itself is extremely dense, is rife with parasites and other disease-carriers, and is full of poisonous plants and animals of all kinds. Yet, archaeologists now know that there was an advanced urban culture in this region which supported large-scale root agriculture, build roads, bridges, and palisades, and dammed rivers for the purpose of fish farming – evidently the rumours told to the early Spanish conquistadores of cities in the jungle were more than just myth. This culture lasted for nearly a millennium until it went into terminal decline around 1550 AD, the jungle reclaiming it thoroughly until satellite imaging recently rediscovered it.

What happened? We’re not sure, but the best theory seems to be that diseases brought by Europeans terminated this Mato Grosso culture, destroying enough of its population that urban existence could no longer be sustained. The result of this was a turn to tribalism, a less complex form more easily sustained by the post-plague population. The descendants of this culture are the Kuikuro people, a Carib-speaking tribe living in the region, and probably also other tribes living in the greater area around the Matto Grosso. In the case of the Mato Grosso city culture, the shock of disease against which they had no immunity destroyed their population, and concomitantly their ability to maintain more complex forms of civilisation.

The conical tower inside the Great Enclosure at Great Zimbabwe.

Photo by Marius Loots via Wikimedia Commons.The second example would be that of the Kingdom of Zimbabwe, centered around its capital of “Great Zimbabwe,” designated as such so as to distinguish it from the 200 or so smaller “zimbabwes” that have been scattered around present-day Rhodesia and Mozambique. Great Zimbabwe, at its peak, housed almost 20,000 people and was the nucleus of a widespread Iron Age culture in southern Africa, and this Bantu culture flourished from the 11th-16th centuries AD before collapsing. It is thought that the decline of Zimbabwean culture was due to the exhaustion of key natural resources which kept them from sustaining their urban culture. The result, if the later state of the peoples in the area is any indicator, was a conversion to the tribal structures more typically associated with sub-Saharan Africa. The direct descendants of the Zimbabwean culture are thought to be the various tribes in the area speaking Shona, a Bantu language group with over 8 million speakers now (post Western medicine and agriculture, of course). Once again, though, we see that when conditions changed – the loss of key resource supports for the urban culture – the shock to the system led to a radical decomplexification of the society involved.

April 4, 2024

QotD: What we mean by the term “indigenous”

Well, if by indigenous we mean “the minimally admixed descendants of the first humans to live in a place”, we can be pretty confident about the Polynesians, the Icelanders, and the British in Bermuda. Beyond that, probably also those Amazonian populations with substantial Population Y ancestry and some of the speakers of non-Pama–Nyungan languages in northern Australia? The African pygmies and Khoisan speakers of click languages who escaped the Bantu expansion have a decent claim, but given the wealth of hominin fossils in Africa it seems pretty likely that most of their ancestors displaced someone. Certainly many North American groups did; the “skraelings” whom the Norse encountered in Newfoundland were probably the Dorset, who within a few hundred years were completely replaced by the Thule culture, ancestors of the modern Inuit. (Ironically, the people who drove the Norse out of Vinland might have been better off if they’d stayed; they could hardly have done worse.)

But of course this is pedantic nitpicking (my speciality), because legally “indigenous” means “descended from the people who were there before European colonialism”: the Inuit are “indigenous” because they were in Newfoundland and Greenland when Martin Frobisher showed up, regardless of the fact that they had only arrived from western Alaska about five hundred years earlier. Indigineity in practice is not a factual claim, it’s a political one, based on the idea that the movements, mixtures, and wholesale destructions of populations since 1500 are qualitatively different from earlier ones. But the only real difference I see, aside from them being more recent, is that they were often less thorough — in large part because they were more recent. In many parts of the world, the Europeans were encountering dense populations of agriculturalists who had already moved into the area, killed or displaced the hunter-gatherers who lived there, and settled down. For instance, there’s a lot of French and English spoken in sub-Saharan Africa, but it hasn’t displaced the Bantu languages like they displaced the click languages. Spanish has made greater inroads in Central and South America, but there’s still a lot more pre-colonial ancestry among people there than there is pre-Bantu ancestry in Africa. I think these analogies work, because as far as I can tell the colonization of North America and Australia look a lot like the Early European Farmer and Bantu expansions (technologically advanced agriculturalists show up and replace pretty much everyone, genetically and culturally), while the colonization of Central and South America looks more like the Yamnaya expansion into Europe (a bunch of men show up, introduce exciting new disease that destabilizes an agricultural civilization,1 replace the language and heavily influence the culture, but mix with rather than replacing the population).

Some people argue that it makes sense to talk about European colonialism differently than other population expansions because it’s had a unique role in shaping the modern world, but I think that’s historically myopic: the spread of agriculture did far more to change people’s lives, the Yamnaya expansion also had a tremendous impact on the world, and I could go on. And of course the way it’s deployed is pretty disingenuous, because the trendier land acknowledgements become, the more the people being acknowledged start saying, “Well, are you going to give it back?” (Of course they’re not going to give it back.) It comes off as a sort of woke white man’s burden: of course they showed up and killed the people who were already here and took their stuff, but we’re civilized and ought to know better, so only we are blameworthy.

More reasonable, I think, is the idea that (some of) the direct descendants of the winners and losers in this episode of the Way Of The World are still around and still in positions of advantage or disadvantage based on its outcome, so it’s more salient than previous episodes. Even if, a thousand years ago, your ancestors rolled in and destroyed someone else’s culture, it still sucks when some third group shows up and destroys yours. It’s just, you know, a little embarrassing when you’ve spent a few decades couching your post-colonial objections in terms of how mean and unfair it is to do that, and then the aDNA reveals your own population’s past …

Reich gets into this a bit in his chapter on India, where it’s pretty clear that the archaeological and genetic evidence all point to a bunch of Indo-Iranian bros with steppe ancestry and chariots rolling down into the Indus Valley and replacing basically all the Y chromosomes, but his Indian coauthors (who had provided the DNA samples) didn’t want to imply that substantial Indian ancestry came from outside India. (In the end, the paper got written without speculating on the origins of the Ancestral North Indians and merely describing their similarity to other groups with steppe ancestry.) Being autochthonous is clearly very important to many peoples’ identities, in a way that’s hard to wrap your head around as an American or northern European: Americans because blah blah nation of immigrants blah, obviously, but a lot of northern European stories about ethnogenesis (particularly from the French, Germans, and English) draw heavily on historical Germanic tribal migrations and the notion of descent (at least in part) from invading conquerors.

One underlying theme in the book — a theme Reich doesn’t explicitly draw out but which really intrigued me — is the tension between theory and data in our attempts to understand the world. You wrote above about those two paradigms to explain the spread of prehistoric cultures, which the lingo terms “migrationism” (people moved into their neighbors’ territory and took their pots with them) and “diffusionism”2 (people had cool pots and their neighbors copied them), and which archaeologists tended to adopt for reasons that had as much to do with politics and ideology as with the actual facts on (in!) the ground. And you’re right that in most cases where we now have aDNA evidence, the migrationists were correct — in the case of the Yamnaya, most modern migrationists didn’t go nearly far enough — but it’s worth pointing out that all those 19th century Germans who got so excited about looking for the Proto-Indo-European Urheimat were just as driven by ideology as the 21st century Germans who resigned as Reich’s coauthors on a 2015 article where they thought the conclusions were too close to the work of Gustaf Kossinna (d. 1931), whose ideas had been popular under the Nazis. (They didn’t think the conclusions were incorrect, mind you, they just didn’t want to be associated with them.) But on the other hand, you need a theory to tell you where and how to look; you can’t just be a phenomenological petri dish waiting for some datum to hit you. This is sort of the Popperian story of How Science Works, but it’s more complex because there are all kinds of extra-scientific implications to the theories we construct around our data.

The migrationist/diffusionist debate is mostly settled, but it turns out there’s another issue looming where data and theory collide: the more we know about the structure and history of various populations, the more we realize that we should expect to find what Reich calls “substantial average biological differences” between them. A lot of these differences aren’t going to be along axes we think have moral implications — “people with Northern European ancestry are more likely to be tall” or “people with Tibetan ancestry tend to be better at functioning at high altitudes” isn’t a fraught claim. (Plus, it’s not clear that all the differences we’ve observed so far are because one population is uniformly better: many could be explained by greater variation within one population. Are people with West African ancestry overrepresented among sprinters because they’re 0.8 SD better at sprinting, or because the 33% higher genetic diversity among West Africans compared to people without recent African ancestry means you get more really good sprinters and more really bad ones?) But there are a lot of behavioral and cognitive traits where genes obviously play some role, but which we also feel are morally weighty — intelligence is the most obvious example, but impulsivity and the ability to delay gratification are also heritable, and there are probably lots of others. Reich is adorably optimistic about all this, especially for a book written in 2018, and suggests that it shouldn’t be a problem to simultaneously (1) recognize that members of Population A are statistically likely to be better at some thing than members of Population B, and (2) treat members of all populations as individuals and give them opportunities to succeed in all walks of life to the best of their personal abilities, whether the result of genetic predisposition or hard work. And I agree that this is a laudable goal! But for inspiration on how our society can both recognize average differences and enable individual achievement, Reich suggests we turn to our successes in doing this for … sex differences! Womp womp.

Jane Psmith and John Psmith, “JOINT REVIEW: Who We Are and How We Got Here, by David Reich”, Mr. and Mrs. Psmith’s Bookshelf, 2023-05-29.

1. aDNA works for microbes too, and it looks like Y. pestis, the plague, came from the steppe with the Yamnaya. It didn’t yet have the mutation that causes buboes, but the pneumonic version of the disease is plenty deadly, especially to the Early European Farmers who didn’t have any protection against it. In fact, as far as we can tell, in all of human history there have only been four unique introductions of plague from its natural reservoirs in the Central Asian steppe: the one that came with or slightly preceded the Yamnaya expansion around 5kya, the Plague of Justinian, the Black Death, and an outbreak that began in Yunnan in 1855. The waves of plague that wracked Europe throughout the medieval and early modern periods were just new pulses of the strain that had caused Black Death. Johannes Krause gets into this a bit in his A Short History of Humanity, which I didn’t actually care for because his treatment of historic pandemics and migrations is so heavily inflected with Current Year concerns, but I haven’t found a better treatment in a book so it’s worth checking it out from the library if you’re interested.

2. I cheated with that “pots not people” line in my earlier email; it usually gets (got?) trotted out not as a bit of epistemological modesty about what the archaeological record is capable of showing, but as a claim that the only movements involved were those of pots, not of people.

March 23, 2024

The Roman Army’s Biggest Building Projects

toldinstone

Published Dec 15, 2023The greatest achievements of the Roman military engineers.

Chapters:

0:00 Introduction

0:38 Marching camps

1:36 Bridges

2:40 Siegeworks

3:26 PIA VPN

4:32 Permanent forts

5:49 Roads

6:24 Frontier defenses

7:41 Canals

8:21 Civilian projects

8:54 The aqueduct of Saldae

(more…)

March 21, 2024

QotD: South Africa under Thabo Mbeki

[During Nelson Mandela’s presidency, Thabo] Mbeki quickly began to insist that South Africa’s military, corporations, and government agencies bring their racial proportions into exact alignment with the demographic breakdown of the country as a whole. But as Johnson points out, this kind of affirmative action has very different effects in a country like South Africa where 75% of the population is eligible than it does in a country like the United States where only 13% of the population gets a boost. Crudely, an organization can cope with a small percentage of its staff being underqualified, or even dead weight. Sinecures are found for these people, roles where they look important but can’t do too much harm. The overall drag on efficiency is manageable, especially if every other company is working under the same constraints.

Things look very different when political considerations force the majority of an organization to be underqualified (and there are simply not very many qualified or educated black South Africans today, and there were even fewer when these rules went into effect). A shock on that scale can lead to a total breakdown in function, and indeed this is precisely what happened to one government agency after another. Johnson notes that this issue, and particularly its effects on service provision to the rural poor, pit two constituencies against each other which many have tried to conflate, but are actually quite distinct. The immiserated black lower class (which the ANC purported to represent) didn’t benefit at all from affirmative action because they weren’t eligible for government jobs anyway, and they vastly preferred to have the whites running the water system if it meant their kids didn’t get cholera. The people actually benefited by Mbeki’s affirmative action policies were the wealthy and upwardly-mobile black urban bourgeoisie, a tiny minority of the country, but one that formed the core of Mbeki’s support.

That same small group of educated and well-connected black professionals was also the major beneficiary of Mbeki’s other signature economic policy: Black Economic Empowerment (BEE). Oversimplifying a bit, BEE was a program in which South African corporations were bullied or threatened into selling some or all of their shares at favorable prices to politically-connected black elites, who generally returned the favor by looting the company’s assets or otherwise running it into the ground (note that this is not the description you will find on Wikipedia). The whole thing was so astoundingly, revoltingly corrupt that even the ANC has had to back off and admit in the face of criticism from the left that something went wrong here.

What made BEE so “successful” is that it was actually far more consensual than you might have guessed from that description. In many cases, the white former owners of these corporations were looking around at the direction of the country and trying to find any possible excuse to unload their assets and get their money out. The trouble was that it was difficult to do that without seeming racist, because obviously racism was the only reason anybody could have doubts about the wisdom of the ANC. The genius of BEE is that it allowed these white elites to perform massive capital flight while simultaneously framing it as a grand anti-racist gesture and a mark of their confidence in the future of the country.

This is one particular instance of a more general phenomenon, which is that at this stage pretty much everybody was pretending that things were going great in South Africa, when things were clearly not, in fact, going great. But this was the late 90s and early 00s, the establishment media had a much tighter hold on information than it does today, and so long as nobody had an interest in the story getting out, it wasn’t going to get out. Everybody who mattered in South Africa wanted the story to be that the end of apartheid had resulted in a peaceful and harmonious society, and everybody outside South Africa who’d spent decades supporting and fundraising for the ANC wanted this to be the story too.

John Psmith, “REVIEW: South Africa’s Brave New World, by R.W. Johnson”, Mr. and Mrs. Psmith’s Bookshelf, 2023-03-20.

March 12, 2024

Vektor CP-1: Recalled to the Mother Ship

Forgotten Weapons

Published Dec 8, 2023The Vektor CP-1 was developed by Lyttleton Engineering Works (who owned the Vektor brand) in 1995 for a South African Police contract. They lost that contract to the Republic Arms RAP-401, but decided to put the CP-1 onto the civilian market instead. It was a pretty decent seller for them, and after a couple years they started importing it into the US. Things went bad when it turned out the the gun wasn’t quite drop-safe, and in late 2000 they were recalled for a repair. Some were repaired and returned to owners, but a great many were simply repurchased by Vektor instead. In light of the recall and potential future problems with the US legal outlook, Vektor USA was dissolved circa 2001.

Mechanically, the CP1 is a gas-delayed blowback pistol in 9mm Parabellum. It came with 12- and 13-round magazines (10 rounds in the US, because of the Assault Weapons Ban). It was hammer fired, and used a polymer frame (the first such made in South Africa). Its futuristic design lines are very deliberate, and its biggest shortcoming is a fairly heavy trigger, for being single action only. It has a somewhat unorthodox trigger safety, and also a Garand-style manual safety in the front of the trigger guard.

In today’s video, we will take a look at both an original configuration example and also one rebuilt after the recall, with a new firing pin block mechanism.

(more…)

March 6, 2024

QotD: Mansa Musa’s disastrous foreign aid to Cairo

Mansa Musa’s good intentions may be the first case in history of failed foreign aid. Known as the “Lord of the Wangara Mines”, Mansa Musa I ruled the Empire of Mali between 1312 and 1337. Trade in gold, salt, copper, and ivory made Mansa Musa the richest man in world history.

As a practicing Muslim, Mansa Musa decided to visit Mecca in 1324. It is estimated that his caravan was composed of 8,000 soldiers and courtiers — others estimate a total of 60,000 — 12,000 slaves with 48,000 pounds of gold and 100 camels with 300 pounds of gold each. For greater spectacle, another 500 servants preceded the caravan, and each carried a gold staff weighing between 6 and 10.5 pounds. When totaling the estimates, he carried from side to side of the African continent approximately 38 tons of the golden metal, the equivalent today of the gold reserves in Malaysia’s central bank — more than countries like Peru, Hungary or Qatar have in their vaults.

On his way, the Mansa of Mali stayed for three months in Cairo. Every day he gave gold bars to the poor, scholars, and local officials. Mansa’s emissaries toured the bazaars paying at a premium with gold. The Arab historian Al-Makrizi (1364-1442) relates that Mansa Musa’s gifts “astonished the eye by their beauty and splendor”. But the joy was short-lived. So much was the flow of golden metal that flooded the streets of Cairo that the value of the local gold dinar fell by 20 percent and it took the city about 12 years to recover from the inflationary pressure that such a devaluation caused.

Orestes R Betancourt Ponce de León, “5 Historic Examples of Foreign Aid Efforts Gone Wrong”, FEE Stories, 2021-06-06.