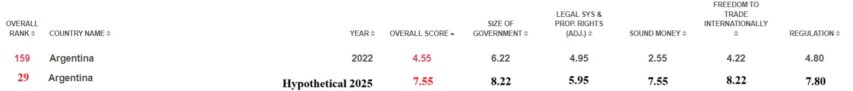

One of Donald Trump’s more interesting announcements shortly after winning the federal election early in November was that he was going to give Elon Musk and Vivek Ramaswamy a formal position to do to the US government’s vast array of bureaucratic organizations what Javier Milei did to Argentina’s bloated national government. Here, scraped from the social media platform formerly known as Twitter, is Devon Eriksen‘s thoughts on how to go about pruning back the “fourth branch” of government:

Since the framers of the Constitution created a federal government with three branches, not four, there are no Constitutional checks on the emergent fourth branch.

Currently, the fourth branch is in many ways the most powerful, and certainly the most destructive, arm of the government.

– It has the privilege of targeting individual citizens on its own initiative, which is forbidden to the three other branches.

– It can interfere their lives in any way it wishes by making a “ruling”.

– The only recourse against a “ruling” is to take the bureaucracy in question to court.

– But the process is the punishment, because this takes months if not years and costs tens if not hundreds of thousands of dollars.

– Until recently, courts have deferred to bureaucrats as a matter of legal precedent. Now they merely do so as a matter of practice.

– But should the bureaucracy lose anyway, the only punishment the court inflicts is that they are told they have to stop doing that specific thing.

– Any fines or legal costs imposed on them punish the taxpayer, not the agent or even the agency.

– And the next, closely related, thing the bureaucracy thinks of to do is once again fair game, until the courts are once again brought in, at further cost, to tell it to stop.

All of this creates a Red Queen Effect.

Citizens must establish their own organizations, and raise donations to engage in constant lawfare, just to retain the rights they haven’t lost yet. And they must win every time to maintain the status quo.

Bureaucrats, on the other hand, can fight endless legal battles using money taken from their victims by the IRS, at no cost to themselves. Any victory they claim, they may keep permanently, while any loss may be refought endlessly simply by a slight variance of the attack.

Obviously, if this system is not changed, all power will accrue to the bureaucracy over time. They will constitute a totalitarian authority over every aspect of the life of every citizen.

This is why the name “DOGE” (Department of Government Efficiency) is a serious mistake.

Look, Elon, I like a joke as much as the next guy, and I do think irreverence is a load-bearing component of checking the bureaucracy, because a false aura of gravitas is one of their defenses against public outrage.

But words mean things.

When you create a check on the bureaucracy and call it the department of government efficiency, you focus the attention, and the correction, on the fact that the bureaucracy is stomping on people’s lives and businesses inefficiently, not on the fact that they are doing so at all.

But the name isn’t my decision. The power of the vote isn’t that granular. I can only elect an administration, not protect it from tactical errors by weighing in on individual policy decisions.

Unless someone with direct power happens to read this.

So, regardless of the name, here’s how an organization might be set up to effectively check federal bureaucracies.

1. DOGE must be responsive, not merely proactive.

Being proactive sounds better in the abstract, but it is much easier for a federal agency to gin up some numbers to fight a periodic overall audit, than it is to fight an investigation of a specific case.

2. DOGE must have direct oversight.

If it must take agencies to court, it is merely a proxy for the citizens whose money is being wasted, and whose rights are being trampled.

Imagine the level of inefficiency, waste, and delay, if your process for addressing bureaucratic abuse simply results in one part of the federal government pursuing an expensive court case against another.

Instead, DOGE must have the power to simply make a ruling, via its own investigation hearing process, which is binding on federal agencies.

Any appeals to the court system must be allowed to trigger their own DOGE investigation (for wasting taxpayer fighting a ruling).

3. DOGE must have the power to punish the agent, not just the agency.

“You have to stop that now” is not a deterrent. Neither is fining the agency, because such fines are paid by the American taxpayer.

DOGE must follow Saul Alinsky’s 11th rule: target individuals, not institutions.

Why?

Because agencies are agencies. They consist of agents.

An agent is someone who acts on behalf of a principal — someone whose interests the agent is supposed to represent.

When the agent is incentivized so that his interests diverge from those of the principal, he will be increasingly likely to act in his own interest, not the principal’s.

This is the Principal-Agent Problem.

An agency is a construct, a theoretical entity. What Vonnegut would call a “granfalloon”.

Agencies do not act, they do not make decisions, they do not have incentives they respond to. Any appearance to the contrary is an emergent property created by the aggregate action of agents.

Every decision, whether we admit it or not, has a name attached to it, not a department. It is that person who responds to incentives.

Agents will favor their own incentives over those of their principal (the American people) unless a counter incentive is present for that specific person.

For this reason, DOGE should, must, have the power to discipline individual employees of the federal agencies it oversees.

This doesn’t just mean insignificant letters of reprimand in a file. It means fines against personal assets, firing, or even filing criminal charges. No qualified immunity.

Yes, you read that right. DOGE must be able to fire other agencies’ staff. I recommend that anyone fired by DOGE be permanently illegible for any federal government job, excluding only elected positions.

4. DOGE investigations must be triggerable by citizen complaints.

This is self-explanatory. It gives DOGE the practical capability to redress individual injustices, and it crowdsources your discovery problem.

Establish a hotline.

5. DOGE must have sufficient power to protect and reward whistleblowers, and punish those who retaliate against them.

6. Bureaucrats must be held responsible for outcomes, not just for following procedure.

Often, procedure is the problem. The precedent must be established, and clearly enforced, that because agents have agency, agents are responsible for using their discretion to ensure efficient, just, and sane outcomes, not just for doing whatever departmental policy allows.

7. DOGE must have an adversarial relationship with the bureaucracies is oversees.

This eliminates the phenomenon of “we investigated ourselves and found no wrongdoing”.

Following the previous recommendation is almost sure to make this happen.

The point is not for DOGE to address every instance of waste or wrongdoing, it is to make bureaucrats act responsibly because they fear an investigation.

In essence, I am imagining DOGE (or some superior name that better reflects the mission) as an entity with a license to treat bureaucrats the way bureaucrats currently treat citizens.