World War Two

Published 14 Sep 2022When Italy leaves WW2, The Nazi German Reich immediately begins occupying the country, and the occupied nations it has held until now.

(more…)

September 15, 2022

Italy Switches Sides in World War Two – WAH 077 – September 11, 1943

“Presentism is … a disease, a contagion here in America as infectious as the Wuhan flu”

Jeff Minick on the mental attitude that animates so many progressives:

My online dictionary defines presentism as “uncritical adherence to present-day attitudes, especially the tendency to interpret past events in terms of modern values and concepts”. To my surprise, the 40-year-old dictionary on my shelf also contains this eyesore of a word and definition.

To be present, of course, is a generally considered a virtue. It can mean everything from giving ourselves to the job at hand — no one wants a surgeon dreaming of his upcoming vacation to St. Croix while he’s cracking open your chest — to consoling a grieving friend.

But presentism is altogether different. It’s a disease, a contagion here in America as infectious as the Wuhan flu. The latter spreads by way of a virus, the former through ignorance and puffed-up pride.

Presentism is what inspires the afflicted to tear down the statues of such Americans as Washington, Jefferson, and Robert E. Lee for owning slaves without ever once asking why this was so or seeking to discover what these men thought of slavery. Presentism is why the “Little House Books” and some of the early stories by Dr. Seuss are attacked or banned entirely.

Presentism is the reason so many young people can name the Kardashians but can’t tell you the importance of Abraham Lincoln or why we fought in World War II.

Presentism accounts in large measure for our Mount Everest of debt and inflation. Those overseeing our nation’s finances have refused to listen to warnings from the past, even the recent past, about the clear dangers of a government creating trillions of dollars out of the air.

Presentism has led America into overseas adventures that have invariably come to a bad end. Afghanistan, for example, has long been known as the graveyard of empires, a cemetery which includes the tombstones of British and Russian ambitions. By our refusal to heed the lessons of that history and our botched withdrawal from Kabul, we dug our own grave alongside them.

H/T to Kim du Toit for the link.

Lahti L-35: Finland’s First Domestic Service Automatic Pistol

Forgotten Weapons

Published 23 Apr 2018When Finland decided to replace the Luger as its service handgun, they turned to Finland’s most famous arms designer, Aimo Lahti. After a few iterations, Lahti devised a short recoil semiautomatic pistol with a vertically traveling locking block, not too different from a Bergmann 1910 or Type 94 Nambu. It was adopted in 1935, but production did not really begin in earnest until 1939 at the VKT rifle factory. Several variations were made as elements of the gun were simplified to speed up production, and the design was also licensed to the Swedish Husqvarna company, which manufactured nearly 10 times as many of the pistols as VKT eventually did.

In today’s video we will look at each of the variations, including one with an original shoulder stock and the early and late military guns as well as the post-war commercial guns marked Valmet instead of VKT.

(more…)

QotD: Protectionism

Any particular protectionist policy sits somewhere on a spectrum. At one end of the spectrum is a scheme of protectionism in which government officials have great discretion in doling out the privilege of tariffs. Some producers get protected; others don’t. Here, the few rob the many.

At the other end of the spectrum, government officials have no discretion in doling out the privilege of tariffs because all industries are equally protected, to the same degree, by tariffs from import competition. Here, everyone robs everyone.

Pick any point along this spectrum, and you’ll find – in practice – some people robbing others but not themselves being robbed; other people robbing others while they themselves also are robbed; and yet other people who do no robbing but who are robbed.

What you’ll not find anywhere along this spectrum is a point at which no robbery occurs, for protectionism is in essence a scheme of organized theft.

Protectionists, as has often been observed, have the ethics of thugs. Regardless of their legerdemain or their excuses – or even their felt intent – they are all apologists for plunderers.

Don Boudreaux, “Bonus Quotation of the Day…”, Café Hayek, 2019-03-17.

September 14, 2022

Whisky – Scotland’s Water of Life

Tasting History with Max Miller

Published 13 Sep 2022

“Americans, particularly the kind of Very Serious people who make up our intelligentsia, are desperate for a good war”

Freddie deBoer thinks he’s sussed out the reason so many Americans are so very, very pro-Ukraine in the ongoing fighting between the Russian invaders and the Ukrainian defenders (beyond the normal desire to “root for the underdog”):

Approximate front-line positions just before the Ukrainian counter-attack east of Kharkiv in early September 2022.

It was not until I was an adult that I realized that the absurd fervor for Desert Storm was in fact about Vietnam. Fifteen years earlier, American helicopters had fled in humiliation from Saigon, and nothing had happened to take the sour taste out of the mouth of Americans since. There was plenty of power projection in that decade and a half, but no great good wars for the United States to win in grand and glorious fashion, unless you worked really hard to talk yourself into Grenada. America had been badly stung by losing a war to a vastly poorer and less technologically-advanced force. Americans had been nursing their wounds all those years. So when Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait, and the “international community” rose to expel him, the country was ready. We were ready for another righteous combat of the Goodies vs. the Baddies. We were ready for the good guys to be the winners again.

This dynamic, I’m certain, is the source of American bloodlust over Ukraine.

We have now spent twenty years without good, noble wars against the Baddies ourselves. Afghanistan was a war effort undertaken in rage and terror, and was accordingly never intelligently conceptualized at the most basic level. The war aim of finding and capturing bin Laden and destroying Al Qaeda gave way to a war on the Taliban that ensured an endless occupation. The Potemkin government we installed was never popular with the people of the country, entailed comical levels of corruption, and showed no ability to train a loyal and effective Afghan army. After 20 years our country tired of spending hundreds of billions on that failure, we left, the government collapsed almost without resistance, and the Taliban are in power again. In Iraq, the basic arguments for the war (WMDs and a Hussein-al Qaeda connection) were swiftly revealed to be bullshit. Saddam’s army fell quickly and he was dispatched after a show trial, but a persistent insurgency inflicted thousands of American casualties. The chaos enabled the rise of ISIS and its various horrors. The new Iraqi government we’ve installed is impossibly corrupt and scores a 31/100 on Freedom House’s ratings of a country’s dedication to political rights and civil liberties. That’s what the United States has gotten for $8 trillion spent on warmaking since 9/11.

America loves a winner, and will not tolerate a loser. So I once heard. Americans, particularly the kind of Very Serious people who make up our intelligentsia, are desperate for a good war. A just war. A war where we win. They’re sick of wars that feel morally complicated, sick of wars that they have to feel queasy about, sick of wars that aren’t just Goodies and Baddies. They are very, very hungry for good war. I think Ukraine is the Desert Storm a lot of people have been waiting for: a war with (they insist) perfectly simplistic moral stakes, an impossibly noble (they assume) set of Goodies, a marauding and senseless (they demand) set of Baddies. All they’re waiting on is victory. And it’s for this reason, this view of war as one big cope, that the pro-Ukraine position is the single most rigidly enforced consensus in our country since 9/11. There is no other issue on which the majority has more vociferously demanded total consensus or more viciously attacked any who dissent or even ask questions. Because America needs a win. People need to believe in a Goodies and Baddies world again.

There are, of course, all manner of hard questions that we could ask, even if we were supportive of Ukraine in this war. That this is a conflict that has constantly inspired left-leaning people to literally say “well, yes, there’s Nazis, but …” might be seen as a matter of some concern. Perhaps, we might just say, isn’t that a little disturbing? But not in this discursive environment. Or we might consider that a total loss for Russia could be one of the most dangerous outcomes for the world even if you support Ukraine. What do you think happens, with a wounded and isolated Russia? Let’s say people get what they want and Putin is deposed. What do you think happens next? We finally get that shining city on a hill in Moscow that we were promised with the collapse of the Soviet Union? That we’ll get the world leader we expected Bagdhad to be in 2003, that a foreign country with foreign people and foreign concerns will suddenly become a docile member of the liberal-capitalist order? Maybe the best post-Putin outcome would be for a similar corrupt autocrat to take his place; at least then there might be stability. A far more likely and more frightening outcome is that leadership is splintered, you have in effect a set of rival warlords squabbling over the spoils, and the world’s largest nuclear arsenal is exposed in a terrifying way. Seems like something to worry about.

But, no. To a degree that genuinely shocks me, hard questions have been forbidden. Complications have been denied. Comparisons to previous conflicts have been forsaken. And this from Democrat and Republican, liberal and leftist, neocon and Never Trumper. It’s constant, everpresent, and relentless, the denial of any complication in the case of Ukraine and Russia. The glee and the gloating and the urge to ridicule anyone who takes even a single step outside of the consensus is remarkable, unlike anything I’ve ever really encountered before. And I find that I can’t even get people to have a conversation about that, a meta-conversation about why the debate on Ukraine is not a debate, about why there are many people who will consider any political position except one that troubles the moral question of Russia’s invasion, about why so many people who learned to speak with care and equivocation during Iraq now insist that there is no complication at hand with this issue at all. I can’t even get a conversation about the conversation going. People get too mad.

Marmite Dynamite Limited Edition — Tasting (Also Re-Tasting The Others, With A Spoon)

Atomic Shrimp

Published 20 Mar 2021More Marmite – I couldn’t get hold of a jar of this for the group tasting last week, but here it is now!

Here’s the previous video: https://youtu.be/MjrBTcnnK6c

QotD: The Wars of Religion and the (eventual) Peace of Westphalia

Thomas Hobbes blamed the English Civil War on “ghostly authority”. Where the Bible is unclear, the crowd of simple believers will follow the most charismatic preacher. This means that religious wars are both inevitable, and impossible to end. Hobbes was born in 1588 — right in the middle of the Period of the Wars of Religion — and lived another 30 years after the Peace of Westphalia, so he knew what he was talking about.

There’s simply no possible compromise with an opponent who thinks you’re in league with the Devil, if not the literal Antichrist. Nothing Charles I could have done would’ve satisfied the Puritans sufficient for him to remain their king, because even if he did everything they demanded — divorced his Catholic wife, basically turned the Church of England into the Presbyterian Kirk, gave up all but his personal feudal revenues — the very act of doing these things would’ve made his “kingship” meaningless. No English king can turn over one of the fundamental duties of state to Scottish churchwardens and still remain King of England.

This was the basic problem confronting all the combatants in the various Wars of Religion, from the Peasants’ War to the Thirty Years’ War. No matter what the guy with the crown does, he’s illegitimate. It took an entirely new theory of state power, developed over more than 100 years, to finally end the Wars of Religion. In case your Early Modern history is a little rusty, that was the Peace of Westphalia (1648), and it established the modern(-ish) sovereign nation-state. The king is the king because he’s the king; matters of religious conscience are not a sufficient casus belli between states, or for rebellion within states. Cuius regio, eius religio, as the Peace of Augsburg put it — the prince’s religion is the official state religion — and if you don’t like it, move. But since the Peace of Westphalia also made heads of state responsible for the actions of their nationals abroad, the prince had a vested interest in keeping private consciences private.

I wrote “a new theory of state power”, and it’s true, the philosophy behind the Peace of Westphalia was new, but that’s not what ended the violence. What did, quite simply, was exhaustion. The Thirty Years’ War was as devastating to “Germany” as World War I, and all combatants in all nations took tremendous losses. Sweden’s king died in combat, France got huge swathes of its territory devastated (after entering the war on the Protestant side), Spain’s power was permanently broken, and the Holy Roman Empire all but ceased to exist. In short, it was one of the most devastating conflicts in human history. They didn’t stop fighting because they finally wised up; they stopped fighting because they were physically incapable of continuing.

The problem, though, is that the idea of cuius regio, eius religio was never repudiated. European powers didn’t fight each other over different strands of Christianity anymore, but they replaced it with an even more virulent religion, nationalism.

Severian, <--–>”Arguing with God”, Rotten Chestnuts, 2020-01-20.

September 13, 2022

Society would be happier if we all paid even less attention to “the tossers of Tinsel Town”

Ian O’Doherty on the malign influence pretty people who mouth other people’s words for the cameras still exude in our popular culture:

They never learn, do they? If the tumultuous events we have all watched with growing horror over the past few years taught us one thing, it is this – people don’t care what the pampered starlets of Hollywood have to say about politics. If we did, then Hillary Clinton would be comfortably enjoying her second term as the pantsuit POTUS, Jeremy Corbyn would be prime minister of the UK and we would all be driving electric cars.

But regular people are smarter than actors, which seems to drive the luvvies wild with fury. Rather than accepting that maybe, just maybe, there is another side to the argument, the tossers of Tinsel Town insist that anyone who doesn’t fully embrace the so-called progressive agenda is simply a monster.

We saw this recently when Jennifer Lawrence, who used to be quite refreshingly down to Earth, proudly admitted that she had to “work so hard … to forgive my dad and my family” for voting Republican. She also, quite wonderfully, spoke about having “recurring nightmares” about Fox News anchor Tucker Carlson.

In the course of her interview for the cover issue of Vogue magazine – that renowned bastion of proletarian agitation – the Hunger Games actress claimed that she was born a Kentucky Republican, was raised as a Kentucky Republican and had considered herself to be a Kentucky Republican, until she watched an episode of 30 Rock. And then her worldview completely changed.

Now most of us would agree that 30 Rock was a brilliant sitcom. After all, it was so ingenious in its construction that it even managed to make Alec Baldwin look likeable. But would anyone think that Liz Lemon’s line, “I’m not a crazy liberal – I just think people should drive hybrid cars”, would be enough to utterly transform someone’s political beliefs?

Apparently, this is what changed everything for Lawrence. She even seemed proud of the fact that a throwaway line in a sitcom triggered some sort of Damascene conversion to what is now so tediously known as “the right side of history”.

Predictably, following the Vogue interview, Lawrence was hailed as a modern-day Joan of Arc – for refusing to be “passive about politics”. But there is no real bravery involved in simply having the courage of other people’s convictions – she knows which way the political wind is blowing and is bending to it. That’s not all that brave, is it?

The Greatest Escapes of World War Two – WW2 Special

World War Two

Published 12 Sep 2022This is an intimate story inspired by real events (notably inspired by the story of a member of the Danish resistance and grandmother of Hans von Knut Skovfoged, Head of Development at PortaPlay. A story told not on the front line, but in the intimate setting of a small Danish village.

(more…)

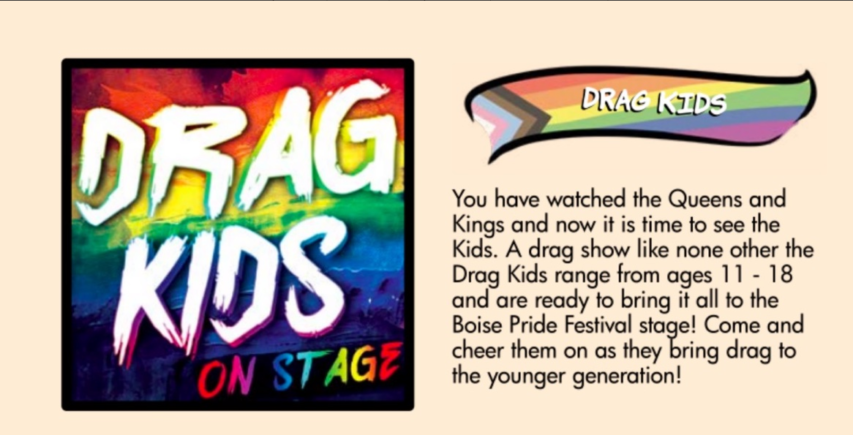

The Boise Pride Festival’s “Drag Kids on Stage”

I’m not sure I could accurately place Boise on a map, but the city’s relative obscurity doesn’t mean it can’t have a really progressive LGBT scene, including a special “Drag Kids” event planned for their Pride Festival:

Remember that California has just passed a new law, SB 1100, to protect local legislative bodies against “bullying” from people who do hateful things like disagreeing with them, and that the recent failure of another (spectacularly offensive) bill in the state legislature was the product of “harassment”, by which the author of the bill meant that the peasantry forcefully and persistently criticized it. And you should definitely read this two–part essay from Bat Cattitude on the technocratic presumption that disagreement with technocrats can only be dangerous extremism.

With that background in mind, consider a modest victory in the most dismal battlefield of the culture war, and then watch the response to it.

This one happens in Boise, a purple town in a red state. This year’s Boise Pride Festival was all set to feature an event called Drag Kids:

“Now it is time to see the kids”, sexy eleven year-olds shaking that dirty little moneymaker on the stage. So hot. So empowering!

[…]

Now, the Big Pivot: Boise Pride pays its bills by soliciting the support of corporate sponsors, so a bunch of corporations suddenly found themselves sponsoring the sexuality-incorporating performances of some hot little eleven year-olds. They quickly began to jump clear of the thing:

Because bigotry still prevails in Amerikkka, see, corporations aren’t brave enough to stand up and support the sexy eleven year-olds in their extremely hot sexiness. Atavists! Prudes!

Now, here come the politicians. The mayor of Boise, Lauren McLean, is Very Disappointed In You All™:

Slogan slogan slogan, slogan slogan, slogan slogan slogan. A spotlight on the critical need for a conversation about standing together!

If you challenged Mayor NPC to publicly identify specific pieces of inflammatory rhetoric that were important and central to the controversy, she couldn’t; she just knows that the “inflammatory rhetoric” box has to be checked, because Mean Republicans objected to something involving an LGBT event, specifics not important. Nor could she explain how sexy children represent the dignity of all people, or respond coherently to a discussion about sexual commodification and the erasure of childhood. She has a list of slogans. She deploys them.

Down the Line – A look into the legacy of the cuts made to the rail network by Doctor Beeching (2008)

Kevin Birch

Published 29 Jul 2013Joe Crowley meets the people who battled to save their local railway lines in the South of England in the 1960’s.

First aired on BBC One 26th October 2008

QotD: J.R.R. Tolkien’s childhood and schooling

One reason highbrow people dislike The Lord of the Rings is that it is so backward-looking. But it could never have been otherwise. For good personal reasons, Tolkien was a fundamentally backward-looking person. He was born to English parents in the Orange Free State in 1892, but was taken back to the village of Sarehole, north Worcestershire, by his mother when he was three. His father was meant to join them later, but was killed by rheumatic fever before he boarded ship.

For a time, the fatherless Tolkien enjoyed a happy childhood, devouring children’s classics and exploring the local countryside. But in 1904 his mother died of diabetes, leaving the 12-year-old an orphan. Now he and his brother went to live with an aunt in Edgbaston, near what is now Birmingham’s Five Ways roundabout. In effect, he had moved from the city’s rural fringes to its industrial heart: when he looked out of the window, he saw not trees and hills, but “almost unbroken rooftops with the factory chimneys beyond”. No wonder that from the moment he put pen to paper, his fiction was dominated by a heartfelt nostalgia.

Nostalgia was in the air anyway in the 1890s and 1900s, part of a wider reaction against industrial, urban, capitalist modernity. As a boy, Tolkien was addicted to the imperial adventure stories of H. Rider Haggard, and it’s easy to see The Lord of the Rings as a belated Boy’s Own adventure. An even bigger influence, though, was that Victorian one-man industry, William Morris, inspiration for generations of wallpaper salesmen. Tolkien first read him at King Edward’s, the Birmingham boys’ school that had previously educated Morris’s friend Edward Burne-Jones. And what Tolkien and his friends adored in Morris was the same thing you see in Burne-Jones’s paintings: a fantasy of a lost medieval paradise, a world of chivalry and romance that threw the harsh realities of industrial Britain into stark relief.

It was through Morris that Tolkien first encountered the Icelandic sagas, which the Victorian textile-fancier had adapted into an epic poem in 1876. And while other boys grew out of their obsession with the legends of the North, Tolkien’s fascination only deepened. After going up to Oxford in 1911, he began writing his own version of the Finnish national epic, the Kalevala. When his college, Exeter, awarded him a prize, he spent the money on a pile of Morris books, such as the proto-fantasy novel The House of the Wolfings and his translation of the Icelandic Volsunga Saga. And for the rest of his life, Tolkien wrote in a style heavily influenced by Morris, deliberately imitating the vocabulary and rhythms of the medieval epic.

Dominic Sandbrook, “This is Tolkien’s world”, UnHerd.com, 2021-12-10.

September 12, 2022

QotD: On the nature of our evidence of the ancient world

As folks are generally aware, the amount of historical evidence available to historians decreases the further back you go in history. This has a real impact on how historians are trained; my go-to metaphor in explaining this to students is that a historian of the modern world has to learn how to sip from a firehose of evidence, while the historian of the ancient world must learn how to find water in the desert. That decline in the amount of evidence as one goes backwards in history is not even or uniform; it is distorted by accidents of preservation, particularly of written records. In a real sense, we often mark the beginning of “history” (as compared to pre-history) with the invention or arrival of writing in an area, and this is no accident.

So let’s take a look at the sort of sources an ancient historian has to work with and what their limits are and what that means for what it is possible to know and what must be merely guessed.

The most important body of sources are what we term literary sources, which is to say long-form written texts. While rarely these sorts of texts survive on tablets or preserved papyrus, for most of the ancient world these texts survive because they were laboriously copied over the centuries. As an aside, it is common for students to fault this or that later society (mostly medieval Europe) for failing to copy this or that work, but given the vast labor and expense of copying and preserving ancient literature, it is better to be glad that we have any of it at all (as we’ll see, the evidence situation for societies that did not benefit from such copying and preservation is much worse!).

The big problem with literary evidence is that for the most part, for most ancient societies, it represents a closed corpus: we have about as much of it as we ever will. And what we have isn’t much. The entire corpus of Greek and Latin literature fits in just 523 small volumes. You may find various pictures of libraries and even individuals showing off, for instance, their complete set of Loebs on just a few bookshelves, which represents nearly the entire corpus of ancient Greek and Latin literature (including facing English translation!). While every so often a new papyrus find might add a couple of fragments or very rarely a significant chunk to this corpus, such additions are very rare. The last really full work (although it has gaps) to be added to the canon was Aristotle’s Athenaion Politeia (“Constitution of the Athenians”) discovered on papyrus in 1879 (other smaller but still important finds, like fragments of Sappho, have turned up as recently as the last decade, but these are often very short fragments).

In practice that means that, if you have a research question, the literary corpus is what it is. You are not likely to benefit from a new fragment or other text “turning up” to help you. The tricky thing is, for a lot of research questions, it is in essence literary evidence or bust. […] for a lot of the things people want to know, our other forms of evidence just aren’t very good at filling in the gaps. Most information about discrete events – battles, wars, individual biographies – are (with some exceptions) literary-or-bust. Likewise, charting complex political systems generally requires literary evidence, as does understanding the philosophy or social values of past societies.

Now in a lot of cases, these are topics where, if you have literary evidence, then you can supplement that evidence with other forms […], but if you do not have the literary evidence, the other kinds of evidence often become difficult or impossible to interpret. And since we’re not getting new texts generally, if it isn’t there, it isn’t there. This is why I keep stressing in posts how difficult it can be to talk about topics that our (mostly elite male) authors didn’t care about; if they didn’t write it down, for the most part, we don’t have it.

Bret Devereaux, “Fireside Friday: March 26, 2021 (On the Nature of Ancient Evidence”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2021-03-26.

As of Saturday night, Pierre Poilievre is now “Hitler” to most of Canada’s legacy media

Of course, he was already well on the way to being “Hitler” even before the landslide voting results were announced:

New Conservative Party of Canada leader Pierre Poilievre at a Manning Centre event, 1 March 2014.

Manning Centre photo via Wikimedia Commons.

First, this was a completely lopsided blowout victory for the Poilievre team. The Jean Charest people, God bless them, had been telling anyone who would listen these last few weeks that their campaign had a strategy to win on points, thanks to their strong support in Quebec. So yeah, that didn’t happen. Poilievre won on the first ballot with almost 70 per cent of the vote; Charest came in second with … not quite 17 per cent. (Leslyn Lewis came in a distant third with less than 10 per cent, which she’ll probably attribute to the WEF controlling the process using mind-controlling nano-bots hidden COVID-19 vaccines or something similarly totally normal and reasonable.)

But yeah. Sixty eight point one five per cent on the first ballot. That’s a pretty clear signal.

To be honest, we at The Line saw that signal being sent pretty clearly many months ago. As Line editor Matt Gurney wrote almost exactly a year ago here, the only thing that was going to stop the Conservatives taking a real turn to the right was going to be a good showing by former leader Erin O’Toole in the 2021 federal election. He failed to deliver, and discredited the notion of success-via-moderation in the process. Conservatives now want the real thing: a big hunk of conservative red meat on their plate. And we never had any doubt that Poilievre was going to be the guy to serve that up for them.

Poilievre now has something that neither of his last two predecessors had. He has the support of the party behind him. Andrew Scheer needed 13 ballots to win in 2017, and even then only barely edged out Maxime Bernier. O’Toole won a more decisive victory against Peter MacKay, but as soon as he tacked back toward the centre, much of the party became palpably angry and uncomfortable with his leadership. Poilievre will not have these problems. The Conservative Party of Canada is his now.

In terms of our federal politics generally, we repeat a point we have been making here and in other places for many months. We think many Canadians, particularly those of the Liberal persuasion, may be shocked by how well Poilieivre will come across to Canadians. We believe there are a lot of people out there, who don’t have blue checkmarks and don’t spend all their time microblogging angrily at each other, who will like a lot of what Poilievre has to say and won’t find him nearly as scary as those who #StandWithTrudeau.

Poilievre has a nasty streak, and a temper, and we’re not sure that he will be able to control either. He could easily destroy himself. He has baggage too, and maybe get too close to the fringe. But if he doesn’t, we think he has a real shot.

And we think he will be helped by the weakness of the Liberals. This government seems exhausted and increasingly overtaken by events. It is also overly reliant on a few tricks. We suspect Canadians are growing tired of a Justin Trudeau smile and vague non-answer. Some Liberal baggage is just the inevitable consequence of a government aging in office. Some of it seems to be more specific to modern Canadian Liberalism, its leader and their unique, uh, quirks. Too many Liberals are blind to these problems, or least pretend to be — probably because they’re not great at admitting they have any problems at all, least not any posed by someone they find as repugnant as Pierre Poilievre. To them, we say this: Hillary thought she’d beat Trump.

It’s been fixed opinion among “mainstream” “conservatives” in Canada that the only way to get elected is to be more like Justin Trudeau. The obvious problem with this notion is that it’s going to be difficult to persuade Canadians to vote for a blue-suited Trudeau — or even an orange-tie-wearing Trudeau — if the original item is still on offer. I personally think Trudeau is a terrible PM, but a lot of people in downtown Toronto, Montreal, and Vancouver clearly disagree with me, and thanks to the Liberals’ hyper-efficient voting pattern, that’s been enough to keep Trudeau in power.