At least for now, most progressives acknowledge that markets and economic growth are necessary. But progressives in academia contend that growth has proved itself secondary to equality efforts — something to be exploited, rather than appreciated. Not just nationally, but worldwide, policymakers and the press regard the subordination of growth to equality to be a benign practice, as in the recent line in the Indian periodical Mint: a policy aimed at “reducing inequality need not hurt growth.”

The redistributionist impulse has brought to the fore metrics such as the Gini coefficient, named after the ur-redistributor, Corrado Gini, an Italian social scientist who developed an early statistical measure of income distribution a century ago. A society where a single plutocrat earns all the income ranks a pure “1” on the Gini scale; one in which all earnings are perfectly equally distributed, the old Scandinavian ideal, scores a “0” by the Gini test. The Gini Index has been renamed or updated numerous times, but the principle remains the same. Income distribution and redistribution seem so crucial to progressives that French economist Thomas Piketty built an international bestseller around it, the wildly lauded Capital.

Through Gini’s lens, we now rank past eras. Decades in which policy endeavored or managed to even out and equalize earnings — the 1930s under Franklin Roosevelt, the 1960s under Lyndon Johnson — score high. Decades where policymakers focused on growth before equality, such as the 1920s, fare poorly. Decades about which social-justice advocates aren’t sure what to say — the 1970s, say — simply drop from the discussion. In the same hierarchy, federal debt moves down as a concern because austerity to reduce debt could hinder redistribution. Lately, advocates of economically progressive history have made taking any position other than theirs a dangerous practice. Academic culture longs to topple the idols of markets, just as it longs to topple statutes of Robert E. Lee.

But progressives have their metrics wrong and their story backward. The geeky Gini metric fails to capture the American economic dynamic: in our country, innovative bursts lead to great wealth, which then moves to the rest of the population. Equality campaigns don’t lead automatically to prosperity; instead, prosperity leads to a higher standard of living and, eventually, in democracies, to greater equality. The late Simon Kuznets, who posited that societies that grow economically eventually become more equal, was right: growth cannot be assumed. Prioritizing equality over markets and growth hurts markets and growth and, most important, the low earners for whom social-justice advocates claim to fight. Government debt matters as well. Those who ring the equality theme so loudly deprive their own constituents, whose goals are usually much more concrete: educational opportunity, homes, better electronics, and, most of all, jobs. Translated into policy, the equality impulse takes our future hostage.

Amity Shlaes, “Growth, Not Equality”, City Journal, 2018-01-21.

April 12, 2020

QotD: The Gini coefficient

April 1, 2020

The Orient Express: King of Trains, Train of Kings

Geographics

Published 29 Nov 2019The journey to the Express was not a simple one. For upper class travellers to enjoy a luxury, non-stop train ride across seven nations, it would take the dream of a lovesick Belgian engineer, with his rather interesting supporting cast: an American industrialist, the inventor of US tabloid journalism, the Prince of Wales, and one of the most prolific mass murderers of the 19th and 20th Centuries.

Credits:

Host – Simon Whistler

Author – Arnaldo Teodorani

Producer – Jennifer Da Silva

Executive Producer – Shell HarrisBusiness inquiries to admin@toptenz.net

March 29, 2020

QotD: Cargo cults, ancient and modern

A cargo cult is a belief system among members of a relatively undeveloped society in which adherents practice superstitious rituals hoping to bring modern goods supplied by a more technologically advanced society. These cults … were first described in Melanesia in the wake of contact with more technologically advanced Western cultures. The name derives from the belief which began among Melanesians in the late 19th and early 20th centuries that various ritualistic acts such as the building of an airplane runway will result in the appearance of material wealth, particularly highly desirable Western goods (i.e., “cargo”), via Western airplanes.

To say that Pacific island societies were “relatively undeveloped” is a euphemism; they were primitive backward people who, when first encountered by European explorers, lived in a Neolithic stage of development far behind that of Mesopotamia in 1,500 B.C. That natives of Melanesia were at least 3,000 years behind Western civilization is simply a fact, but facts are now racism. Nevertheless, the point about cargo cult thinking is that these primitive islanders were unable to comprehend the advanced social and economic systems that produced, e.g., steam-powered ships, airplanes and the manufactured goods that the white man’s mechanical contrivances delivered. Utterly ignorant of how and why “cargo” had been produced and transported to their remote islands, the natives were understandably mystified when the arrival of “cargo” was interrupted. So they resorted to imitative rituals by which they believed the return of “cargo” might magically be reinstated.

The 21st-century American might laugh at these primitive superstitions, except that similarly ignorant “monkey see, monkey do” behaviors can be observed in our own society every day. My favorite example is the teenage boy who observes that girls are interested in athletes. The star basketball player in high school is popular with the girls, and so lower-status teenage boys — including the ones with zero athletic aptitude — will often emulate the athletic boys in terms of their attitudes, manners and clothing. This is why you see so many dorky suburban white boys wearing Nikes, NFL jerseys, etc., slouching around and speaking in a rap-influenced slang: “Wazzup, bruh?” These behavioral styles are an attempted imitation of popular black athletes. The clumsy adolescent white boy lacks the essential substance of the black athlete’s appeal, yet superstitiously believes (in cargo-cult manner) that he can obtain popularity by performing a superficial imitation.

Robert Stacy McCain, “The Cargo Cult Mentality”, The Other McCain, 2019-12-20.

March 20, 2020

QotD: Absolute and relative poverty

… in that historical sense, a GDP per capita of $600 a year. Or the current global one, something like $8,000 (depends upon who is doing the counting a bit for that one). That we’re worrying about $34,000 a year, that this is poverty, is exactly the example we need of how well that American capitalism has worked over those centuries.

That the poor of our nation live better than 90 percent of anyone only 100 years ago, better than anyone at all from more than 200 years ago, shows just how fabulous an economic system it is.

Sure, it’s not perfect, it could do with some revisions here and there, but this system — the rule of law, markets, and capitalism — delivers in the one thing that truly matters: raising the living standards of the people, most especially poor people. Even more, no other economic system has managed this at all.

Tim Worstall, “Appalachia’s woes show the success of American capitalism”, Washington Examiner, 2018-01-09.

March 18, 2020

QotD: The “magic” of capitalism

Warren Buffett has told us that there’s something magical about American capitalism. This isn’t quite true, because other countries have achieved much the same thing. What is true about it is that it is the system itself which has caused the incredible wealth we all enjoy in this modern world. Buffett writes:

In 1776, America set off to unleash human potential by combining market economics, the rule of law and equality of opportunity. This foundation was an act of genius that in only 241 years converted our original villages and prairies into $96 trillion of wealth.

Other places which did much the same thing — that mixture of capitalism, the rule of law and free markets — achieved much the same end. We generally refer to those places as the developed world, while those that didn’t are still the Third World. There is nowhere at all that has become rich, absent some vast natural resource, without adopting this system.

We can show this, too, with the numbers from Angus Madison. The average GDP per capita over history, all countries, all empires, was some $600 a year or so — That’s in today’s dollars, meaning history was, by our standards, abject destitution for everyone. This is also why we use $1.90 a day (at modern American prices) as our measure of global absolute poverty. Because that’s just what the past was and we celebrate when people, a country, a nation, rise above that historical existence.

Tim Worstall, “Appalachia’s woes show the success of American capitalism”, Washington Examiner, 2018-01-09.

March 1, 2020

“When you’re driving a fancy car, you’re an avatar for everyone else’s bad boss, useless trust-fund roommate, or absent workaholic father”

At Car and Driver, Ezra Dyer confirms what most of us already suspected about the folks who drive expensive rides:

Excuse us if you’ve already devoured the latest volume of the Journal of Transport & Health, but the March issue contains the results of a novel experiment that tested a cherished automotive stereotype. The study is entitled “Estimated Car Cost as a Predictor of Driver Yielding Behavior for Pedestrians,” but you can think of it as, “Are BMW drivers really jerks or what?”

Okay, so it was more nuanced than that. The authors of the study sent four pedestrians — black female, black male, white female, white male — to crosswalks in the Las Vegas area to see how many drivers would yield. The overall results were pretty dismal, with a yield rate of only about 28 percent out of 461 cars. Cars yielded more often to female and white pedestrians than male and nonwhite pedestrians, although not enough either way to register as statistically significant. The only factor that consistently predicted yielding behavior was the value of the car. Notably, the study’s authors estimated the book value on all 461 cars, so the 2004 Mercedes S-class that’s worth $5000 didn’t get ascribed automatic snob appeal.

[…]

However, if you’re driving an actual exotic, something way far up the food chain, behavior changes again. Everyone yields to the Rolls or the Lambo because cars like that are so over the top, they make you interesting by association. Plus: most people don’t know anybody with a car like that; thus they can’t associate it with anyone awful. The ultra-expensive car, and the driver, are a curiosity. What’s that guy’s deal? He probably invented that fake grass that goes between the pieces of sushi. And good for him! But the guy in the 911? He can wait an extra two turns at the four-way intersection. Probably deserves it.

Our not-scientific conclusions: If you expect fellow road users to demonstrate courtesy, you should drive either a 1984 Renault Alliance or a Lamborghini Aventador SVJ roadster. But either way, and to everybody in between: Yield at the damn crosswalks.

February 22, 2020

February 21, 2020

QotD: Thought experiment

If you were hovering above Earth looking to be born randomly into any time period in human history, you’d pick now if you had any brains. And if you could pick a place, you’d pick a Western liberal democracy, and probably the United States of America (though as much as it pains me to say it, you wouldn’t be crazy to pick Canada or the U.K. or Holland). Sure, if you could pick being rich, white, and male — and didn’t really care too much about the plight of others — you might take the 1950s. But even then, your choices for food, entertainment, etc. would be terribly curtailed compared to today. If you chose to be a billionaire in 1917, you could still die from a minor infection, and good Thai food would be entirely unknown to you. You’d certainly never enjoy watching a Star Wars movie on an IMAX screen in air conditioning. In other words, while your homes would be bigger and cooler if you were a billionaire in 1917, a typical orthodontist in Peoria in 2017 is in many respects much richer than a billionaire a century earlier.

Still, that’s not the deal on offer. You have to buy an incarnation lottery ticket, and the results would be random.

I’m not big on dividing people up by abstract categories, and I certainly don’t mean them to be pejorative. But as a historical matter, being born poor, gay, black, Jewish, ugly, weird, handicapped, etc. today may certainly come with some problems or challenges, but on the whole those traits are less of a shackle or barrier than at any time in the past. The only trait where I think it might be a closer call is dumbness. All other things being equal, a not-terribly-intelligent person with a good work ethic and some decent values might have had more opportunities before machines replaced strong backs. But even here, I can think of lots of exceptions.

Jonah Goldberg, “America and the ‘Original Position'”, National Review, 2017-12-22.

February 13, 2020

Here’s a deceptive factoid … time for you to get angry to suit someone’s political agenda

Did you know that “Three Billionaires Have More Wealth Than Half of America”!!!???!!! Are you angry now? You’re supposed to be, because this factoid was concocted specifically to make people irrationally angry. Daniel C. Jensen explains how this sound bite was created:

People between 0 and 24 years of age account for about 32 percent of the United States population of 320 million. Almost all of them are going to be in the bottom half of the wealth distribution for reasons including diaper rash and puberty. That means they account for about 63 percent of the “bottom half of the wealth distribution.” Should it surprise us that some kid fresh out of college does not “hold any stocks or bonds”? Or a kid fresh out of the womb?

Then we must consider people with mental and physical disabilities. They will also tend to be in the bottom half of the wealth distribution because they face greater challenges to building wealth. “About 56.7 million people — 19 percent of the population — had a disability” at last count, according to the United States Census Bureau. But there is overlap between the disabled 19 percent and the young 32 percent of the population. If we assume disabilities are evenly distributed in the population, then young people and non-young disabled people account for 45 percent of the population. So we have now accounted for 90 percent of the “160 million Americans in the bottom half of the wealth distribution.”

Next, we must think about other groups who have had limited wealth-building opportunities. What about the 2.2 million people in jail and prison? What about people in their late twenties who pursued PhDs, law degrees, medical residencies, etc., and are just beginning their careers? Now we are close to accounting for 100 percent of the “bottom half of the wealth distribution.” But this wealth distribution is not what any sensible person would expect it to be.

Maybe the factoid is true. Maybe Jeff Bezos, Bill Gates, and Warren Buffet have more wealth than all of the infants, children, students, handicapped, prisoners, and postgrads combined. But you don’t need a PhD to figure out that’s not useful knowledge. Even if the factoid is true, it’s deceitful. Whoever created it was obviously trying to manipulate people. And we uncovered this deception with nothing but some simple knowledge of the US population.

Next time you encounter an economic factoid, remember that it might be pitting a bunch of newborns against Jeff Bezos, and that hardly seems fair. Thankfully, you can save those babies from certain defeat simply by knowing some basic statistics about your country.

January 22, 2020

QotD: National “wealth”

All the wealth we’ve accumulated is ultimately between our ears.

While working on my book, I read all these different accounts of where capitalism comes from. I was amazed by how many of them start from the assumption that wealth is … stuff. Depending on which Marxist you’re talking to, capitalism is the ill-gotten-booty of the Industrial Revolution, slavery, imperialism, and the rest. I don’t want to get into all of that here — there will be plenty of time when the book comes out.

But all of these assumptions are based on the idea that having stuff makes you rich. Now, in fairness, that’s true for individuals. But it doesn’t really work that way for societies. Writing about Venezuela earlier this week is what got this in my head. Venezuela is poor and getting poorer by the minute: Babies are dying from starvation.

Meanwhile, Venezuela has the largest proven oil reserves in the world. According to lots of people, not just Marxists, this should make no sense. Oil is valuable. If you have more of it than anyone else, you should be able to make money. For a decade, the American Left loved Hugo Chávez and then Nicolás Maduro because they allegedly redistributed all of the country’s wealth from the rich to the poor. These dictators were using The Peoples’ resources for the common good. Blah blah blah.

It turns out that the greatest resource a country has is its institutions. In economics, an institution is just a rule, which is why the rule of law in general and property rights in particular are the most important institutions there are, with the exception of the family. Take away the rule of law in any country, anywhere and that country will get very poor, very fast. Stop protecting the fruits of someone’s labor, enforcing legal contracts, guarding against theft from the state or the mob (a distinction without a difference in Venezuela’s case) and wealth starts to evaporate.

But even that is too complicated. Oil is worthless on its own. If you went back in time to the Arabian Peninsula before oil became a valuable commodity, you wouldn’t look at the squabbling nomads and call them rich, even though they were playing polo with a goat’s head above billions of barrels of oil. Go get lost in the Amazon by yourself. What would you rather have, a map or big-ass diamond? The diamond only has value once you get out of the jungle, but you can’t get out without the map.

Jonah Goldberg, “America and the ‘Original Position'”, National Review, 2017-12-22.

December 12, 2019

Explaining the decline in library usage

At the Continental Telegraph, Tim Worstall refutes the claims that it’s the evil right wingers (in this specific case, British Tories) that are driving the library out of business:

“Nottingham central library” by JuliaC2006 is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Despite spending more money, library use, measured in terms of at least one visit per year, fell from 48.2% of adults to 39.7% of adults. I make that as roughly 1/5th of the adults that were using them not doing so in 5 years. 17% sounds slightly on the conservative side.

And if this was about “austerity”, you’d expect visits to be rising, rather than falling from 39.7% to 32.9% since the Conservatives/Lib Dems took over. Because the thing with libraries is that they suit the time rich and cash poor. If you’ve not got much else to do, you can spend time walking to a library, getting a book, walking home and easily finding time in the fortnight to read it. And 9-5 hours don’t bother you. There’s areas of the country, like Weston-Super-Mare, stuffed full of retired people and libraries are popular.

If you’re working all week you have to get to a library in your day, park your car, pay for parking, same on return, and make sure to set aside the time to do the reading, you might decide libraries aren’t that convenient.

The decline of libraries is a success story for us. We created them because books were very expensive once. Owning a giant library was the mark of a rich man. Paper was expensive, printing was expensive, binding was expensive. Over the decades, we figured out how to do this cheaper. Then we figured out how to do retailing cheaper. And then we got e-books which take production costs to near zero. Books are cheap. Cheap enough that most of us don’t want the faff of libraries. So, close some of them.

November 27, 2019

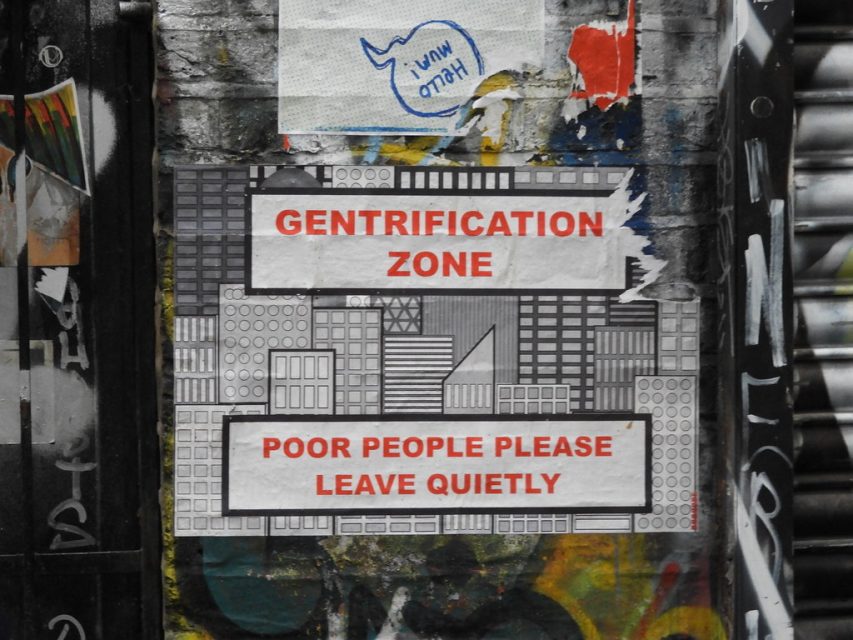

The “Gentrification” debate

In Quillette, Coleman Hughes explains the furor over gentrification in many big American cities:

“Shoreditch Graffiti” by Kit-Kat is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

The word “gentrification” was coined in 1964 to describe the influx of wealthy newcomers into low-income inner-city neighborhoods, resulting in rising property values, changes in neighborhood culture, and displacement of original residents. Though gentrification predates the modern era, it has only become the target of criticism in recent decades, as cities like Washington, D.C., Atlanta, and Boston have witnessed rapid transformations. Opponents of gentrification have ranged from residents directly affected by it to wealthy college students directly responsible for it, as well as prominent Democrats such as Bernie Sanders, Cory Booker, and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez.

Critics of gentrification give two main reasons for their opposition: (1) wealthy newcomers drive up monthly rents, thereby displacing original residents; and (2) rapid change to neighborhood culture represents an injustice to original residents. Both critiques are magnified by the presumed skin color of the gentrifiers and the gentrified, who tend to be white and black or Hispanic, respectively.

Though such critiques may seem reasonable at first glance, neither of them survive scrutiny. Not only is gentrification harmless, it’s actually beneficial. Indeed, for reasons I will lay out, it’s exactly the kind of thing that progressives should support.

Let’s begin with the charge that gentrification displaces original residents. Two economists used data from the 2000 U.S. Census and the 2010-2014 American Community Survey to track individual outcomes for all residents of “gentrifiable” — or low-income inner-city — neighborhoods in America’s one hundred largest metropolitan areas. The largest study of its kind, it divided residents of gentrifiable neighborhoods into two categories based on educational attainment. Their findings refute the displacement narrative conclusively.

[…]

On the whole, progressives ought to love gentrification. It makes black inner-city homeowners wealthier. Among less-educated homeowners — who are majority non-white and comprise over a quarter of the total population in gentrifiable neighborhoods — those who remained in gentrified neighborhoods saw a $15,000 increase in the value of their homes due to gentrification. Among more-educated homeowners — who are also majority non-white — those who remained saw a $20,000 increase in property value.

What’s more, gentrification breaks up concentrated poverty and reduces residential segregation. Progressives have frequently observed that poor blacks are more likely to live in concentrated poverty than poor whites. As a result, they lose out on the advantages that come with living in a mixed-income neighborhood. Gentrification helps solve this problem. Moreover, progressives often observe that residential segregation remains pervasive half a century after the 1968 Fair Housing Act. Gentrification helps solve that problem too.

November 17, 2019

October 23, 2019

QotD: Climbing Maslow’s Pyramid again

[Commenting on a story about the re-introduction of heritage apples to the British market through the work of the wildlife charity People’s Trust for Endangered Species.]

If people want little orchards of native (well, you know) apples then people should have little orchards of native apples. As long as, of course, they’re creating and maintaining those little orchards of native apples at their own expense. This is, after all, what liberalism means, that the peeps get to do what the peeps want. And if we’re to add some Burkean conservatism so that it’s the little platoons sorting it out for themselves then all the better.

As long as no one is being forced to pay for this through taxation then what could possibly be the problem?

At another level this is climbing Maslow’s Pyramid again. At one level of income we’ll take fruit in the only way we can, seasonally and in a limited manner. We get richer, technology advances, we can have apples year round – but that does mean trade, commercially sized operations and the inevitable limited selection. We get richer again and now we’ve more than sufficiency, let’s have that variety back again.

After all, it’s not as if we’re not seeing this right across the food chain, is it?

That roast beef of Olde Englande was most certainly better than the bully beef from Argentina or the Fray Bentos pie. As is the best grass fed British beef of today. But we moved through the cycle to get from most not being able to eat any beef, to all being able to have bad beef, to now again thinking more about the quality – we have a more than sufficiency of beef and can be picky about it.

Tim Worstall, “I fully approve of this”, Tim Worstall, 2017-10-22.