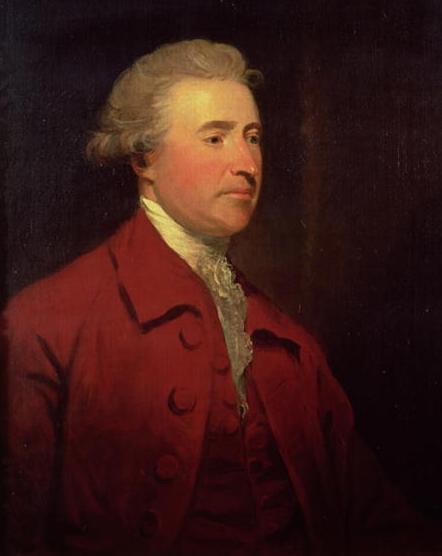

At Samizdata, Niall Kilmartin republishes part of a much older post out as background on Edmund Burke (who I haven’t yet read):

Portrait of Edmund Burke (1729-1797), circa 1770-1780 after a painting of 1774 by James Northcote.

Original in the Royal Albert Museum & Art Gallery via Wikimedia Commons.

When I first started reading Edmund Burke, it was for the political wisdom his writings contained. Only many years later did I start to benefit from noticing that the Burke we know – the man proved a prophet by events and with an impressive legacy – differed from the Burke that the man himself knew: the man who was a lifelong target of slander; the one who, on each major issue of his life, gained only rare and partial victories after years or decades of seeing events tragically unfold as he had vainly foretold. Looking back, we see the man revered by both parties as the model of a statesman and thinker in the following century, the hero of Sir Winston Churchill in the century after. But Burke lived his life looking forwards:

- On America, an initial victory (repeal of the Stamp Act) was followed by over 15 years in the political wilderness and then by the second-best of US independence. (Burke was the very first member of parliament to say that Britain must recognise US independence, but his preferred solution when the crisis first arose in the mid-1760s was to preserve – by rarely using – a prerogative power of the British parliament that could one day be useful for such things as opposing slavery.)

- He vastly improved the lot of the inhabitants of India, but in Britain the first result of trying was massive electoral defeat, and his chosen means after that – the impeachment of Warren Hastings – took him 14 years of exhausting effort and ended in acquittal. Indians were much better off, but back in England the acquittal felt like failure.

- Three decades of seeking to improve the lot of Irish Catholics, latterly with successes, ended in the sudden disaster of Earl Fitzwilliam’s recall and the approach of the 1798 rebellion which he foresaw would fail (and had to hope would fail).

- The French revolutionaries’ conquest of England never looked so likely as at the time of his death in 1797. It was the equivalent of dying in September 1940 or November 1941.

It’s not surprising that late in his life he commented that the ill success of his efforts might seem to justify changing his opinions. But he added that, “Until I gain other lights than those I have“, he would have to go on being true to his understanding.

Burke was several times defeated politically – sometimes as a direct result of being honest – and later (usually much later) resurged simply because his opponents, through refusing to believe his warnings, walked into water over their heads and drowned, doing a lot of irreversible damage in the process. Even when this happened, he was not quickly respected. By the time it became really hard to avoid noticing that the French revolution was as unpleasant as Burke had predicted, all the enlightened people knew he was a longstanding prejudiced enemy of it, so “he loses credit for his foresight because he acted on it”, as Harvey Mansfield put it. (Similarly, whenever ugly effects of modern politics become impossible to ignore, people like us get no credit from those to whom their occurrence is unexpected because we were against them “anyway”.)

Lastly, I offer this Burke quote to guide you when people treat their success in stealing something from you (an election, for example) as evidence of their right to do so:

“The conduct of a losing party never appears right: at least, it never can possess the only infallible criterion of wisdom to vulgar judgments – success.”