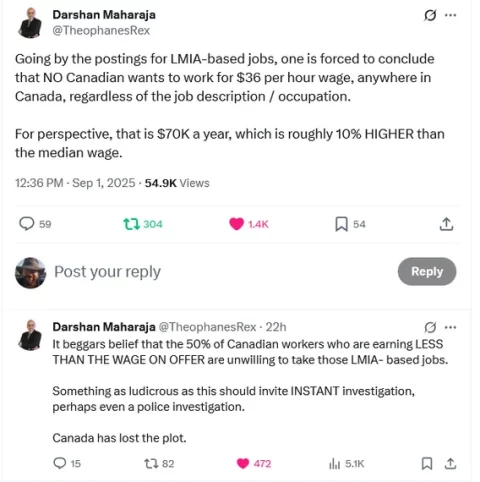

The 1880s and 1890s saw an enormous expansion in the number of newspapers in America. New printing technologies had drastically reduced barriers to entry in the newspaper field, while the emergence of consumer advertising was making the business more lucrative. By the election of 1896, there were forty-eight daily newspapers in New York (Brooklyn had several more), each vying for the attention of some portion of the city’s three million souls. The major papers routinely produced three or four editions a day, and as many as a dozen on a hot news day, making for a 24/7 news environment long before the term was coined. The individual newspapers were distinguished by their politics, ethnic, and class orientations. They advocated vigorously, often shamelessly, and occasionally dishonestly for the interests of their readers. Similar dynamics were afoot everywhere. America, in the 1890s, was noisy as hell.

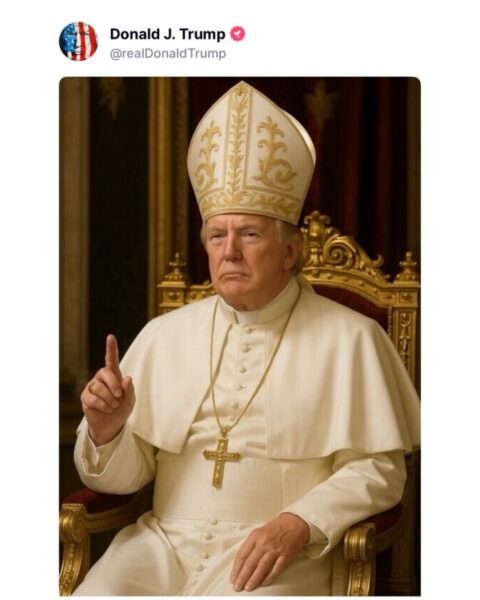

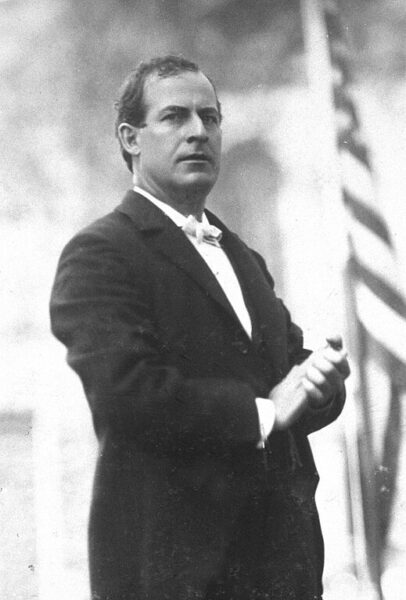

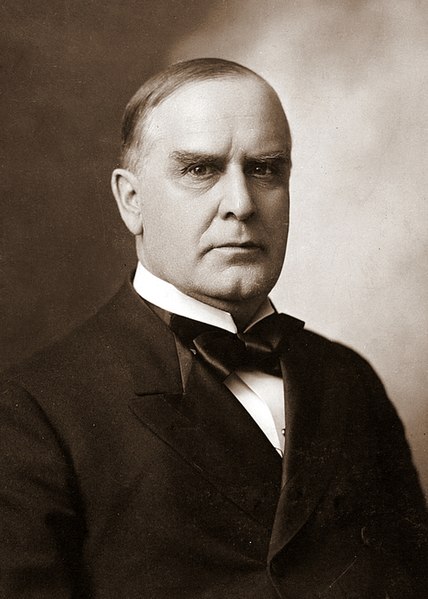

Republican nominee William McKinley was the respectable candidate in 1896, heavily favoured. He had a state-of-the-art organization, buckets of money, and vast newspaper support, even among important Democratic publishers such as Joseph Pulitzer. The Democrats fielded William Jennings Bryan, who looked to be the weak link in his own campaign. He was a relatively unknown and untested ex-congressman from Nebraska, just thirty-six-years-old, a messianic populist with a mesmerizing voice and radical views. A last-minute candidate, he was selected on the convention floor over Richard P. Bland, against the protests of the party establishment.

Bryan broke all the norms of politics in 1896. At the time, it was believed that the dignified approach to campaigning was to sit on one’s porch and let party professionals speak on one’s behalf. Grover Cleveland had made eight speeches and journeyed 312 miles in his three presidential campaigns (1884, 1888, 1892). Bryan spent almost his entire campaign on the rails, holding rallies in town after town. He travelled 18,000 miles and talked to as many as five million Americans. He unabashedly championed the indigent and oppressed against Wall Street and Washington elites.

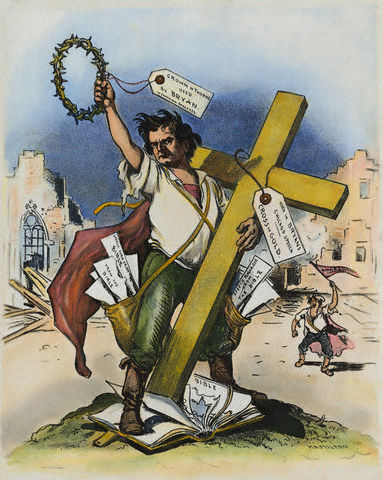

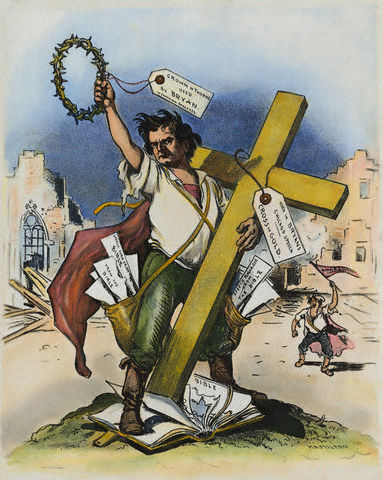

Inflation was the central issue of the 1896 campaign. The US was on the gold standard at the time, meaning that the amount of money in circulation was limited by the amount of gold held by the treasury. Gold happened to be scarce, resulting in an extended period of deflation, a central factor in the major economic depression of the early 1890s. The effects were felt disproportionately by the poor and working class. Bryan advocated the monetization of silver (in addition to gold) as a means of increasing the money supply and reflating the economy. This was viewed by the establishment as an economic heresy (not so much today). Bryan was viewed as a saviour by his followers, and that’s certainly how he saw himself.

The New York Sun heard among the Democrats “the murmur of the assailants of existing institutions, the shriek of the wild-eyed”. The New York Herald warned that Bryan’s supporters, disproportionately in the west and south, represented “populism and Communism” and “crimes against the nation” on par with secession. The New York Tribune warned that the Democrats’ “burn-down-your-cities platform” would lead to pillage and riot and “deform the human soul”. The New York Times asked, in all sincerity, “Is Mr. Bryan Crazy?” and spoke to a prominent alienist who was convinced that the election of the Democrat would put “a madman in the White House”. That Bryan’s support was especially strong among new Americans — the nation was amid an unprecedented wave of immigration — was especially disconcerting to the establishment. His followers were a “freaky”, “howling”, “aggregation of aliens”, according to the Times.

The only major New York newspaper to support the Democrats that season was Hearst’s New York Journal, a new, inexpensive, and wildly popular daily. I wrote about this in The Uncrowned King: The Sensational Rise of William Randolph Hearst. Loathed by the afore-mentioned respectable sheets, the Journal became the de facto publicity arm of the Bryan campaign and Hearst became the Elon Musk of his time.

William McKinley, 1896.

Photo by the Courtney Art Studio via Wikimedia Commons.

The unobjectionable McKinley didn’t offer Democrats much of a target, but his campaign was being managed and funded by Ohio shipping and steel magnate Mark Hanna. The Journal had learned that Hanna and a syndicate of wealthy Republicans had previously bailed out McKinley from a failed business venture. Hearst’s cartoonists portrayed Hanna as a rapacious plutocratic brute (accessorized with bulging sacks of money or the white skulls of laborers) and McKinley as his trained monkey or puppet: “No one reaches the McKinley eye or speaks one word to the McKinley ear without the password of Hanna. He has McKinley in his clutch as ever did hawk have chicken … Hanna and his syndicate are breaking and buying and begging and bullying a road for McKinley to the White House. And when he’s there, Hanna and the others will shuffle him and deal him like a deck of cards.” The cartoons were criticized as cruel, distorted, and perverted. They were hugely effective.

Caught off guard by Bryan’s tactics, but unwilling to put McKinley on the road, Hanna instead arranged for 750,000 people from thirty states to visit Canton, Ohio and see McKinley speak from his front porch. He meanwhile made some of the most audacious fundraising pitches Wall Street had ever heard. Instead of asking for donations, he “levied” banks and insurers a percentage of their assets, demanding the Carnegies, Rockefellers, and Morgans pay to defend the American way from democratic monetary lunatics. Standard Oil alone coughed up $250,000 (the entire Bryan campaign spent about $350,000). Hanna printed and distributed a mind-boggling 250 million documents to a US population of about 70 million (the mails were the social media of the day), and fielded 1,400 speakers to spread the Republican gospel from town to town. All of this was unprecedented.

The Republicans generated their own conspiracy theories to counter the stories about Hanna’s controlling syndicate. Pulitzer’s New York World published a series of articles on The Great Silver Trust Conspiracy — “the richest, the most powerful and the most rapacious trust in the United States”. Bryan was said to be a puppet of this “secret silver society”, for which the World had no evidence beyond that the candidate was popular in silver mining states.

There were violent motifs throughout the campaign. The Republicans accused the Democrats of fostering division and rebellion, threatening national unity by pitting the south and the west against the east and the Mid-West. This was charged language with the Civil War still in living memory. Hanna funded a Patriotic Heroes’ Battalion comprising Union army generals who held 276 meetings in the last months of the campaign. They would ride out in full uniforms to a bugle call, advising the old soldiers who came out to see them to “vote as they shot”. Said one of their number: “The rebellion grew out of sectionalism … We cannot tolerate, will not tolerate, any man representing any party who attempts again to disregard the solemn admonitions of Washington to frown down upon any attempt to set one portion of the country against another.” Senior New York Republicans vowed that if the Democrats were elected, “we will not abide the decision”. These belligerent tactics were cheered by the majority of New York papers.

Democratic and populist leader William Jennings Bryan, climaxed his career when when he gave his famous “Cross of Gold” speech which won him the nomination at the age of 36.

Grant Hamilton cartoon for Judge magazine, 1896 via Wikimedia Commons.

Bryan did nothing to cool tempers by claiming, in his famous “cross of gold” speech, that he and working-class Americans were being crucified by financial and political elites.

On it went. There were many echoes of 1896 in 2024. The polarized electorate, the last-minute candidate, record spending, unprecedented campaign tactics, populism and personal charisma, relentless ad hominem attacks, class and culture and regional warfare, inflation, immigration, racism, misinformation and conspiracy theories, comedians and plutocrats, threats of authoritarianism and violence and revolution, all of it massively amplified, and sometimes generated, by messy new media.

Of course, some of the echoes are coincidental, and there are also many contrasts. It was a different electorate. The alignment of the parties bore little resemblance to what we see today. Bryan, aside from his megalomania and zealotry, was as personally decent as Trump isn’t. And Bryan lost the campaign.

My point is I don’t think it’s an accident that the likes of Bryan and Trump — mavericks who thoroughly dominate their parties (both thrice nominated) through a direct and unshakeable bond with their followers — surface when the public sphere is most chaotic. New media environments, by their nature, are amateurish, turbulent, unsettling. There are fewer guardrails, which is a major reason outsiders and their followers gravitate to them. They see a way to change the rules and end-run established media (establishment candidates are naturally more comfortable using established channels to reach voters). New forms of political communication develop, contributing to new political norms, tactics, and strategies, and long-lasting political realignments.

For better or worse.