In Reason, Liz Wolfe covers some of the head-scratchers former National Security Advisor H.R. McMaster revealed about working for Donald Trump:

Donald Trump addresses a rally in Nashville, TN in March 2017.

Photo released by the Office of the President of the United States via Wikimedia Commons.

What might a second Trump White House be like? In his new book, At War with Ourselves: My Tour of Duty in the Trump White House, Lt. Gen. H.R. McMaster, who served as national security adviser to Donald Trump (for one year), characterizes Oval Office meetings as “exercises in competitive sycophancy” where advisers would greet him with lines like “your instincts are always right” or “no one has ever been treated so badly by the press”.

Trump, meanwhile, would come up with crazy concepts, and float them: “Why don’t we just bomb the drugs?” (Also: “Why don’t we take out the whole North Korean Army during one of their parades?”)

This is one man’s account, of course. McMaster’s word should not be taken as gospel, and some of his frustration might stem from his dismissal, or his foreign-policy prescriptions being at times ignored by his boss. But it’s a somewhat revealing look behind the curtain at policy-setting in a White House helmed by an especially mercurial commander in chief, who “enjoyed and contributed to interpersonal drama in the White House and across the administration”.

It also shows how quickly Trump fantasies have percolated through the Republican Party, namely the “let’s just bomb Mexico to get rid of the cartels” line, which Trump has been toying with since roughly 2019 (or possibly more like 2017, after he chatted with Rodrigo Duterte, former president of the Philippines, who had promised to kill 100,000 drug traffickers during his first six months as president). A few years prior, in 2015, he had suggested that Mexico was sending rapist and drug-traffickers across the southern border, and that we’d need to build a wall between the two countries, but it wasn’t until nine American citizens were killed in Mexico that Trump trotted out the idea of declaring cartels foreign terrorist organizations and using military might to eradicate them.

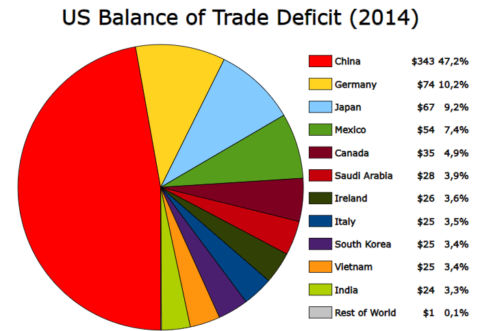

Trump’s line from 2019 has now become standard fare, notes The Economist: The Republican primary debates included lots of tough talk on Mexico, specifically on the bombing front, with Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis claiming he’d send special forces down there on Day One. Right-wing think tanks have embraced the messaging, with articles headlined “It’s Time to Wage War on Transnational Drug Cartels”. Taking cues from other members of her party, Georgia Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene asked why “we’re fighting a war in Ukraine, and we’re not bombing the Mexican cartels”. Whether it’s economic protectionism (10 percent across-the-board tariffs, with 60 percent tariffs imposed on Chinese imports) or Mexico-bombing, Trump has near-magical abilities to get other members of his party to accept something previously regarded as absurd.