Overly Sarcastic Productions

Published 29 Jul 2022The grandest epic cycle this side of the Aegean! Today let’s talk about the tale of which The Iliad only makes up a tiny (if impressive) fraction!

Pst! Wanna know more about Quintus Smyrnaeus’s Posthomerica? Watch Blue’s Historymaker video about him HERE: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wfHGQ…

And if you want to know more about the historical, archaeological precedent that indicates some form of this story REALLY HAPPENED, watch Blue’s video on Mycenaean Greece HERE: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cki-9…

(more…)

December 2, 2022

Legends Summarized: The Trojan War

November 26, 2022

QotD: The search for “authenticity”

The search for authenticity is not only futile but actively harmful, both psychologically and socially, for in general, authenticity is thought to require behavior without the restraints of normal civilized conduct, amongst which are the capacity and willingness on occasion to be hypocritical and insincere. Of course, the precise amount of hypocrisy and insincerity that one should indulge in is always a matter of judgment, but authenticity is brutish if it means saying and doing whatever one wants whenever one wants it.

Shakespeare knew that authenticity, in this sense, is for most people impossible and in all cases undesirable. The first few lines of Sonnet 138 should be enough to prove it:

When my love swears that she is made of truth,

I do believe her, though I know she lies,

That she may think me some untutored youth,

Unlearnèd in the world’s false subtleties.

Thus vainly thinking that she thinks me young,

Although she knows my days are past the best,

Simply I credit her false speaking tongue:

On both sides thus is simple truth suppressed.Should Shakespeare abandon his love because he knows she is inauthentic in what she says? Of course not:

Oh, love’s best habit is in seeming trust …

Away, then, with your self-esteem, your true self and your authenticity, and all the bogus desiderata of modern psychology.

Theodore Dalrymple, “Lose Yourself”, Taki’s Magazine, 2018-11-10.

November 11, 2022

Canada, the Great War, and Flanders Fields

The History Guy: History Deserves to Be Remembered

Published 3 May 2021Canadians would distinguish themselves in the Great War, and the words of Canadian John McCrae would come to, perhaps more than any other, encapsulate the sacrifices of the soldiers of that war. The story of one of the most important poems about war ever written deserves to be remembered.

(more…)

September 5, 2022

The Tragic Life of Rudyard Kipling

The History Guy: History Deserves to Be Remembered

Published 14 Aug 2019The life of the youngest-ever winner of the Nobel Prize for literature, Rudyard Kipling, was filled with tragedy. He survived a difficult childhood to go on to become one of the most celebrated authors of his day, penning such classics as The Jungle Book and Just So Stories. But only one of his children would survive him and his legacy has been tied to some of his out-dated political beliefs. The History Guy remembers the tragic life of Rudyard Kipling.

(more…)

August 9, 2022

QotD: Fusty old literary archaism

For as long as I can remember, readers have been trained to associate literary archaism with the stuffy and Victorian. Shielded thus, they may not realize that they are learning to avoid a whole dimension of poetry and play in language. Poets, and all other imaginative writers, have been consciously employing archaisms in English, and I should think all other languages, going back at least to Hesiod and Homer. The King James Version was loaded with archaisms, even for its day; Shakespeare uses them not only evocatively in his Histories, but everywhere for colour, and in juxtaposition with his neologisms to increase the shock.

In fairy tales, this “once upon a time” has always delighted children. Novelists, and especially historical novelists, need archaic means to apprise readers of location, in their passage-making through time. Archaisms may paradoxically subvert anachronism, by constantly yet subtly reminding the reader that he is a long way from home.

Get over this adolescent prejudice against archaism, and an ocean of literary experience opens to you. Among other things, you will learn to distinguish one kind of archaism from another, as one kind of sea from another should be recognized by a yachtsman.

But more: a particular style of language is among the means by which an accomplished novelist breaks the reader in. There are many other ways: for instance by showering us with proper nouns through the opening pages, to slow us down, and make us work on the family trees, or mentally squint over local geography. I would almost say that the first thirty pages of any good novel will be devoted to shaking off unwanted readers; or if they continue, beating them into shape. We are on a voyage, and the sooner the passengers get their sea legs, the better life will be all round.

David Warren, “Kristin Lavransdatter”, Essays in Idleness, 2019-03-21.

July 11, 2022

British Transport Films: Elizabethan Express (1954)

mikeknell

Published 6 May 2014This 1954 documentary is uploaded in a couple of places, but here it is without breaks and in the correct aspect ratio. One of the classic railway films.

June 28, 2022

History of Rome in 15 Buildings 15. Keats-Shelley House

toldinstone

Published 2 Oct 2018For well over a century, the “Odes” of John Keats have been boring high school students, enchanting lovers of poetry, and giving scholars of English literature interesting things to overinterpret. When he died in 1821, however, Keats was virtually unknown – an anonymous member of Rome’s large community of travelers and expatriates in the last years of the Grand Tour.

To see the story and photo essay associated with this video, go to:

https://toldinstone.com/keats-shelley…

April 2, 2022

Afghan Traditional Jezail

Forgotten Weapons

Published 1 Feb 2017The Jezail is the traditional rifle of the Afghan tribal fighter, although it originated in Persia (Iran). Distinctive primarily for its uniquely curved style of buttstock, these rifles still maintain a symbolic importance although they are utterly obsolete.

Every jezail is a unique handmade weapon, but they all share some basic traits. They are typically built around complete lock assemblies, from captured guns or bought/traded parts. The barrel is typically quite long and rifled, and the caliber is generally .50 to .75 inch. Unlike the domestic American flintlock long rifles, the jezail is meant for war and not hunting.

http://www.patreon.com/ForgottenWeapons

Cool Forgotten Weapons merch! http://shop.bbtv.com/collections/forg…

If you enjoy Forgotten Weapons, check out its sister channel, InRangeTV! http://www.youtube.com/InRangeTVShow

January 1, 2022

Merry Olde England

Sebastian Milbank on the often disparaged nostalgic view of “the good times of old England”:

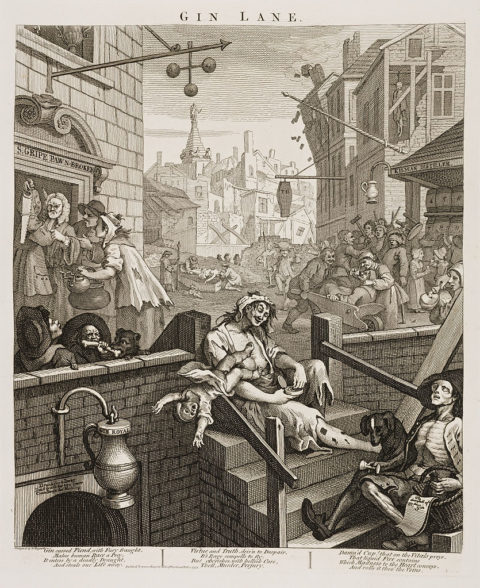

Gin Lane, from Beer Street and Gin Lane. A scene of urban desolation with gin-crazed Londoners, notably a woman who lets her child fall to its death and an emaciated ballad-seller; in the background is the tower of St George’s Bloomsbury.

The accompanying poem, printed on the bottom, reads:

Gin, cursed Fiend, with Fury fraught,

Makes human Race a Prey.

It enters by a deadly Draught

And steals our Life away.

Virtue and Truth, driv’n to Despair

Its Rage compells to fly,

But cherishes with hellish Care

Theft, Murder, Perjury.

Damned Cup! that on the Vitals preys

That liquid Fire contains,

Which Madness to the heart conveys,

And rolls it thro’ the Veins.

Wikimedia Commons.

The decadence and excess of the city is of a piece with puritanical restraint

William Wordsworth wrote:

They called Thee Merry England, in old time;

A happy people won for thee that name

With envy heard in many a distant clime;

And, spite of change, for me thou keep’st the same

Endearing title, a responsive chime

To the heart’s fond belief; though some there are

Whose sterner judgments deem that word a snare

For inattentive Fancy, like the lime

Which foolish birds are caught with. Can, I ask,

This face of rural beauty be a mask

For discontent, and poverty, and crime;

These spreading towns a cloak for lawless will?

Forbid it, Heaven! and Merry England still

Shall be thy rightful name, in prose and rhyme!Merry England is an easily mocked concept in today’s society, but in my view it carries a perennial insight: that the decadence and excess of the city is of a piece with puritanical restraint. Both apparently opposite features reflect an urban sophistication and the ruling imperative of commerce. The moneymaking frenzy of cities like London gave rise to excessive consumption and the relaxing of prior moral and social norms. Yet the 17th century Puritans were in large part cityfolk, alienated from rural tradition and well represented amongst bankers, merchants and urban middle class trades and professions.

William Hogarth’s most famous engraving is Gin Lane, which shows a street filled with people immiserated by the gin craze, a child toppling out of its mother’s arms, emaciated figures dying in the open, madmen dancing with corpses, a pawn-shop with the grandeur of a bank eagerly sucking in objects of domestic industry and converting them into gin money. Less well known is the image that accompanied it, the engraving Beer Street. In this latter engraving, plump and prosperous individuals pause from their labour to receive huge foaming mugs of ale, buxom housemaids flirt with cheerful tipplers, bright inn signs are painted, buildings are going up, and the pawn-shop is going out of business.

Merry England is an image of a society centred on human life and happiness rather than the demands of commerce. Here labour and rest both have their place: noble objects like a fine building and a bounteous meal are provided by hard work, but once completed, time is devoted to appreciating and relishing the finished product. Decoration and adornment are the outward sign of this; they are by their nature a form of abundance. The finite object of labour and production thus gives rise to an infinite realm of feast, celebration, adornment and signification. This enchanted public sphere, shaped to the human person, is limitless within its limits, and points beyond itself to the truly limitless and eternal world of the transcendent.

In the commercially determined sphere of modernity, it is instead work and consumption that are rendered limitless. The objects have become entirely ones of consumption — there is no limit to the consumption of gin, which stands in for all consumer objects. Hogarth shows us the humane objects of household industry — the good cooking pots, the tongs, the saw and the kettle — replaced with money. Liquidity is everywhere, capital has broken down the social order, removing all distinctions of sex, age and class. Now all persons and all things are joined together by a single seamless system of predation.

The alternative that many advocated to this situation was embodied in the Temperance movement: a Puritan-dominated enterprise which saw drinking as a threat to industry as well as the spiritual and moral health of the nation. This is a deep tendency in the British character: the impulse to look upon poverty and distress as a culpable disease and to preach individual self-restraint as the cure. Puritans were often well-to-do, literate townspeople, whose collective refusal to participate in dancing, drama, drinking, gambling, racing and boxing not only set them apart from the boisterous lower orders, but also from the quaffing, hunting, hawking and whoring nobility.

November 3, 2021

QotD: English literature

Here one comes back to two English characteristics that I pointed out, seemingly rather at random, at the beginning of the last chapter. One is the lack of artistic ability. This is perhaps another way of saying that the English are outside the European culture. For there is one art in which they have shown plenty of talent, namely literature. But this is also the only art that cannot cross frontiers. Literature, especially poetry, and lyric poetry most of all, is a kind of family joke, with little or no value outside its own language-group. Except for Shakespeare, the best English poets are barely known in Europe, even as names. The only poets who are widely read are Byron, who is admired for the wrong reasons, and Oscar Wilde, who is pitied as a victim of English hypocrisy. And linked up with this, though not very obviously, is the lack of philosophical faculty, the absence in nearly all Englishmen of any need for an ordered system of thought or even for the use of logic.

George Orwell, “The Lion And The Unicorn: Socialism and the English Genius”, 1941-02-19.

October 25, 2021

QotD: Individual tastes

Taste is not learned out of books; it is not given from one person to another. Therein lies its profundity. At school, fatuous masters would say of poems they didn’t like, using the old Latin saw, De gustibus non disputandem est — there’s no accounting for taste. And so there isn’t. Taste is like a perverse coral: it grows slowly and inexorably into unpredictable shapes, precisely because it’s an offshoot of living iteself. Acquiring taste, then, is not a result of study; it’s a talent for living life.

Lawrence Osborne, The Accidental Connoisseur, 2004.

September 20, 2021

QotD: English jingoism

In England all the boasting and flag-wagging, the “Rule Britannia” stuff, is done by small minorities. The patriotism of the common people is not vocal or even conscious. They do not retain among their historical memories the name of a single military victory. English literature, like other literatures, is full of battle-poems, but it is worth noticing that the ones that have won for themselves a kind of popularity are always a tale of disasters and retreats. There is no popular poem about Trafalgar or Waterloo, for instance. Sir John Moore’s army at Corunna, fighting a desperate rear-guard action before escaping overseas (just like Dunkirk!) has more appeal than a brilliant victory. The most stirring battle-poem in English is about a brigade of cavalry which charged in the wrong direction. And of the last war, the four names which have really engraved themselves on the popular memory are Mons, Ypres, Gallipoli and Passchendaele, every time a disaster. The names of the great battles that finally broke the German armies are simply unknown to the general public.

The reason why the English anti-militarism disgusts foreign observers is that it ignores the existence of the British Empire. It looks like sheer hypocrisy. After all, the English have absorbed a quarter of the earth and held on to it by means of a huge navy. How dare they then turn round and say that war is wicked?

It is quite true that the English are hypocritical about their Empire. In the working class this hypocrisy takes the form of not knowing that the Empire exists. But their dislike of standing armies is a perfectly sound instinct. A navy employs comparatively few people, and it is an external weapon which cannot affect home politics directly. Military dictatorships exist everywhere, but there is no such thing as a naval dictatorship. What English people of nearly all classes loathe from the bottom of their hearts is the swaggering officer type, the jingle of spurs and the crash of boots. Decades before Hitler was ever heard of, the word “Prussian” had much the same significance in England as “Nazi” has to-day. So deep does this feeling go that for a hundred years past the officers of the British Army, in peace-time, have always worn civilian clothes when off duty.

George Orwell, “The Lion And The Unicorn: Socialism and the English Genius”, 1941-02-19.

March 6, 2021

History-Makers: Sappho

Overly Sarcastic Productions

Published 5 Mar 2021It’s no use, dear algorithm, I cannot research, for Sappho has crushed me with longing for lost poetry!

SOURCES & Further Reading: Sappho: fragments by Jonathan Goldberg, “Girl, Interrupted: Who Was Sappho?” for The New Yorker by Daniel Mendelsohn (https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/20…), “Sappho” from The Poetry Foundation (https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poet…)

Our content is intended for teenage audiences and up.

PATREON: https://www.Patreon.com/OSP

PODCAST: https://overlysarcasticpodcast.transi…

DISCORD: https://discord.gg/osp

MERCH LINKS: http://rdbl.co/osp

OUR WEBSITE: https://www.OverlySarcasticProductions.com

Find us on Twitter https://www.Twitter.com/OSPYouTube

Find us on Reddit https://www.Reddit.com/r/OSP/

February 14, 2021

History’s Best(?) Couples — Valentine’s Day Special

Overly Sarcastic Productions

Published 5 Feb 2021Celebrate Valentine’s Day with a look at some of the best couples in history. Well, “Best” is a stretch — definitely most entertaining — but the pairings on display today are FAR from healthy. Enjoy the slow descent into insanity that is “Me Discussing These Stories”.

SOURCES & Further Reading: Suetonius’ Twelve Caesars, Plutarch’s Parallel Lives: Julius Caesar, China: A History by John Keay, “Song of Everlasting Sorrow” by Bai Juyi, Smithsonian Magazine & Biography.com entries on Marie Antoinette & Louis XVI.

Our content is intended for teenage audiences and up.

TRACKLIST: “Scheming Weasel (faster version),” “Local Forecast – Elevator”, “Sneaky Snitch” Kevin MacLeod (incompetech.com)

Licensed under Creative Commons: By Attribution 4.0 License

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/b…PATREON: https://www.Patreon.com/OSP

PODCAST: https://overlysarcasticpodcast.transi…

DISCORD: https://discord.gg/osp

MERCH LINKS: http://rdbl.co/osp

OUR WEBSITE: https://www.OverlySarcasticProductions.com

Find us on Twitter https://www.Twitter.com/OSPYouTube

Find us on Reddit https://www.Reddit.com/r/OSP/

February 6, 2021

QotD: Political virtue signalling in everyday conversation

At the time, I was struck by the presumption — the belief that everyone present would naturally agree — that opposition to Brexit and a disdain of Trump were things we, the customers, would without doubt have in common. That the poem’s sentiment of friendship and community was being soured by divisive smugness escaped our local academic, whose need to let us know how leftwing he is was apparently paramount. The subtext was hard to miss: “This is a fashionable restaurant and its customers, being fashionable, will obviously hold left-of-centre views, especially regarding Brexit and Trump, both of which they should disdain and wish to be seen disdaining by their left-of-centre peers.” And when you’re out to enjoy a fancy meal with friends and family, this is an odd sentiment to encounter from someone you don’t know and whose ostensible job is to make you feel welcome.

It wouldn’t generally occur to me to shoehorn politics into an otherwise routine exchange, or into a gathering with strangers, or to presume the emphatic political agreement of random restaurant customers. It seems … rude. By which I mean parochial, selfish and an imposition — insofar as others may feel obliged to quietly endure irritating sermons, insults and condescension in order to avoid causing a scene and derailing the entire evening. The analogy that comes to mind is of inviting the new neighbours round for coffee and then, just before you hand over the cups to these people you’ve only just met, issuing a lengthy, self-satisfied proclamation on the merits of mass immigration, high taxes and lenient sentencing. And then expecting nodding and applause, rather than polite bewilderment.

David Thompson, “The Blurting”, David Thompson, 2019-09-04.