Atun-Shei Films

Published 9 Oct 2019Happy Leif Erikson Day! Allow me to regale you with the saga of the daring Viking who sailed to North America five hundred years before Columbus (that hack) and called it Vinland. We all know his name and his famous deeds – but what sort of man was Leif Erikson?

Support Atun-Shei Films on Patreon ► https://www.patreon.com/atunsheifilms

#LeifErikson #Viking #History

Watch our film ALIEN, BABY! free with Prime ► http://a.co/d/3QjqOWv

Reddit ► https://www.reddit.com/r/atunsheifilms

Twitter ► https://twitter.com/alienbabymovie

Instagram ► https://www.instagram.com/atunsheifilms

Merch ► https://atun-sheifilms.bandcamp.com

September 7, 2020

Who Was Leif Erikson?

August 16, 2020

February 20, 2020

So that’s why John Cabot got hired!

Anton Howes explains something that I’d wondered about in the latest edition of his Age of Invention newsletter:

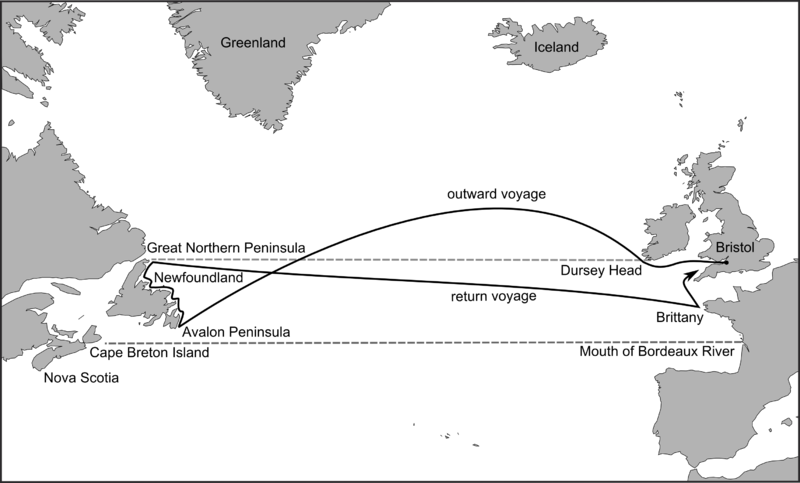

Route of John Cabot’s 1497 voyage on the Matthew of Bristol posited by Jones and Condon: Evan T. Jones and Margaret M. Condon, Cabot and Bristol’s Age of Discovery: The Bristol Discovery Voyages 1480-1508 (University of Bristol, Nov. 2016), fig. 8, p. 43.

Wikimedia Commons.

… in 1550 the English were still struggling with latitude. Their inability to find it, unlike their Spanish and Portuguese rivals, was one of the main things holding them back from voyages of exploration.

The replica of John Cabot’s ship Matthew in Bristol harbour, adjacent to the SS Great Britain.

Photo by Chris McKenna via Wikimedia Commons.The traditional method of navigation for English pilots was to simply learn the age-old routes. They were trained through repetition and accrued experience, learning to recognise particular landmarks and using a lead and line – just a thin rope weighted with some lead – to determine their location from the depth of the water. Cover the lead with something sticky, and you might bring up some sediment from the sea floor to double-check: a pilot would learn the kinds of sand and pebbles from to expect from different areas. And when they travelled out to sea, away from the coastline, they used a basic system of dead reckoning, taking their compass bearings from a known location, estimating their speed, and keeping in a particular direction for long enough. Or at least hoping to. They might keep track of their progress on a wooden traverse table, inserting pegs to indicate how far they had sailed, but it was ultimately a matter of rough estimation. Should they make any mistake — in terms of their speed, heading, or point of departure — they might easily get lost. But it was still a matter of trying to follow an already-known route. And English mariners of the 1550s did not even know that many routes.

For a voyage of exploration, by contrast, landmarks and sediment from the sea floor would be seen for the first time rather than recalled. By definition, there was no route to follow. So to launch their own voyages of discovery, the English needed to learn a new skill. They needed to look to the heavens.

Celestial navigation — measuring the altitude of heavenly bodies and then using geometry to determine one’s latitude on the earth’s surface — was by the 1550s already hundreds of years old. It had primarily been used to cross the deserts of North Africa and the Middle East — seas of sand, in which there might also be no landmarks from which to take bearings — and to navigate the Indian Ocean. Thus, while pilots in the Atlantic and the Mediterranean stuck to dead reckoning and soundings, Islamic navigators had for centuries used quadrants and astrolabes to take their bearings at sea. By the mid-fifteenth century, these instruments and techniques had found their way to Europe, where they were put to use especially by Portuguese, Spanish, and Italian explorers, along with additional instruments such as the cross-staff.

[…]

So for decades, English explorations relied on foreigners who either knew the routes that the English pilots didn’t, or who at least possessed the skill of mathematical, celestial navigation. The Italian explorer John Cabot (Zuan Chabotto), when he sailed to Newfoundland from Bristol in the late 1490s, was able to take latitude readings (he may even have been familiar with the older Islamic navigational practices, as he claimed to have visited Mecca). When Cabot died, the English expeditions that set out from Bristol in 1501-3 relied on Portuguese pilots from the mid-Atlantic islands of the Azores. And John Cabot’s son, Sebastian Cabot, who was involved in a few English expeditions, was so expert in mathematical navigation that he was eventually appointed pilot major for the entire Spanish Empire, making him responsible for the training and licensing of all its pilots — a position he held for three decades. When he led a voyage of exploration on behalf of Spain in 1526-30, a few English merchants became investors so that they could justify sending with him an English mariner, Roger Barlow, to secretly learn the Spanish routes across the Atlantic and have immediate knowledge if an onward route to Asia was discovered (as it turned out, South America got in the way).

November 29, 2019

England’s early search for new markets

In the latest installment of Anton Howes’ Age of Invention, he looks at the multiple crises that afflicted England in the mid-sixteenth century and some of the reactions to those setbacks:

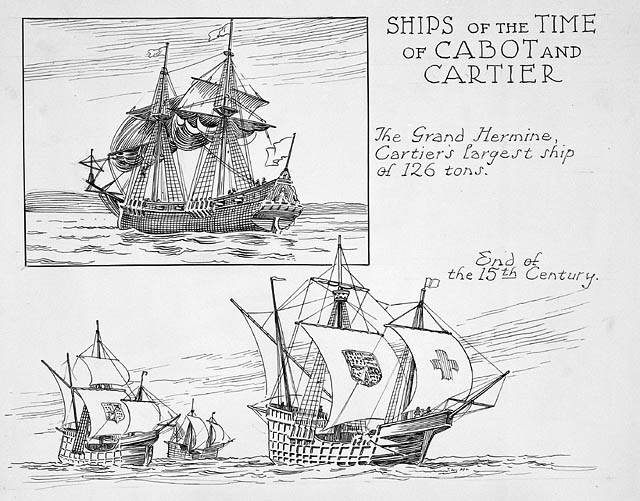

Ships from the period of John Cabot (Giovanni Caboto) and Jacques Cartier.

Illustration by Thomas Wesley McLean (1881-1951) via Wikimedia Commons.

From the 1540s through to the 1560s, [England] was beset by religious uproar, high inflation, hunger, rural and then urban unemployment, a fall-off in its major export trades, and widespread unrest. It was diplomatically isolated too. And I did not even mention the epidemics: the terrifying “sweating sickness” returned in 1551, deadly influenza swept the country in 1557, and in 1563 some 17,000 people in London were reportedly killed by the plague.

Yet, in the face of such problems, innovation in England began to pick up pace. The country, having once been a scientific and technological backwater, began to show signs of catching up. Why?

[…] The fall-off in trade with Europe, for example, seems to have had something to do with spurring the voyages of exploration in search of a north-west and north-east passage to the East Asia. Having lost Antwerp as a place to sell cloth in 1551, the English went in search of an arctic route to northern China and Japan. The expert geographers believed that those regions had a similar climate to that of Antwerp and the surrounding Netherlands, and so reasoned that the Japanese would therefore demand the same kinds of cloth. Although the English expeditions from 1553 onwards did not find a passage to Japan, they did establish trade routes with Russia via the White Sea, and they began to more actively consider the exploration and colonisation of North America. More importantly, with those voyages of exploration came greater experience of navigation, and it was not long before English ships were circumnavigating the globe (Francis Drake in 1577-80). Improvements to navigational techniques and instruments, as well as the ships themselves followed.

So it is tempting to think that necessity was initially the mother of invention, and that the many navigational and shipbuilding improvements of late-sixteenth-century England were its result. But I don’t think that this narrative quite works. I do not believe that necessity was the mother of invention.

For a start, voyages of navigation had already been attempted a number of times, long before the more successful ones in the early 1550s. The first explorers had reputedly gone west from Bristol in 1465, and certainly from 1480. And soon after the announcement of Columbus’s discoveries in the 1490s, the Venetian Zuan Chabotto (aka John Cabot), had sailed from Bristol with Henry VII’s blessing and claimed Newfoundland for both crown and Catholicism. Cabot had even hoped to found a penal colony on his second voyage in 1497, though for some reason the king did not provide the criminals. Throughout the early sixteenth century, the voyages continued. John Rastell, brother-in-law to Thomas More, the famous statesman and author of Utopia, in 1517 went in search of a north-west passage (though he never got beyond Ireland, because his crew decided it would be better to leave him there and sell the ship’s cargo in Bordeaux). Yet another voyage went west with Henry VIII’s support in 1527, but it mostly just found other Europeans — fishing fleets from Spain, Portugal, and France off the coast of Newfoundland (the English had made some catches there in the early 1500s, but apparently could not compete), and the Spanish everywhere else. The expedition made its way down to the Caribbean and then went home, with little to report. So people had already gone off exploring, long before the mid-sixteenth-century English commercial crisis. It suggests that there had already been both a latent supply and demand for such explorations.

September 14, 2019

Apocrypha: WW1 Tour Sneak Peek

Forgotten Weapons

Want to see all of my Apocrypha behind-the-scenes videos? They are a perk for Patrons who help directly support Forgotten Weapons:

http://www.patreon.com/ForgottenWeapons

Cool Forgotten Weapons merch! http://shop.bbtv.com/collections/forg…

I partnered up with Military Historical Tours to guide a World War One battlefield tour this week, and I figured I’d give you a bit of a peek into it. We are looking at the war chronologically, starting with a day in Belgium to look at the German attack in 1914, visiting the remains of Fort de Loncin in Liege and the Mons cemetery. Next was a day in Ypres for the stagnation into trench warfare in 1915, seeing the Dodengang up on the Yser and then the Bayernwald trenches, Passchendaele Museum, and Kitchener’s Wood. The year of 1916 marks two of the huge Western Front offensives, and we took one day on the Somme (Beaumont-Hamel and Lochnagar Crater) and a day at Verdun (Driant’s command post and tomb, Fort Vaux, Fleury Village, and the Douaumont Ossuary). Today we move to the Chemin des Dames to look at the disastrous French Nivelle Offensives at the Plateau de Californie and the Caverne du Dragons, and tomorrow we will see the arrival of significant American forces and the Hundred Days Offensive the ended the war, through the sites of Les Mares Farm, Belleau Wood, and Blanc Mont. We have a great group of people along, and it’s been a lot of fun, if quite sobering at times. I hope to see you on a future tour!

Contact:

Forgotten Weapons

6281 N. Oracle #36270

Tucson, AZ 85704

August 9, 2019

QotD: Early milestones in aviation

… on June 15th 1919 Captain John Alcock and Lieutenant Arthur Brown landed their Vickers Vimy airplane in a bog near Connemara, County Galway and thereby completed the first successful transatlantic flight: They had set off from St John’s, Newfoundland about fourteen hours earlier. What with having to get to the airport three hours early to shuffle through Homeland Security, we haven’t as a practical matter improved much on flight time over the last hundred years. It was also the first transatlantic air mail delivery, as, shortly before takeoff, the Royal Mail decided to give Alcock and Brown a couple of sacks of post for Britain.

A couple of weeks later, on July 6th 1919 the first east-west transatlantic flight landed at Mineola on Long Island. The RAF airship R34 had left East Fortune in Scotland four days earlier, having been hastily converted to hold passengers, and with a plate welded to an engine exhaust pipe to enable it to cook and serve hot food, which is more trouble than most airlines would go to today. A tabby kitten called Wopsie who served as the crew’s mascot stowed away on the flight, and because nobody at the Long Island end knew anything about landing large airships Major E M Pritchard parachuted out a little early, and became the first man to land on North American soil by air from Europe.

These briefly famous men did not get to savor their celebrity for long: Major Pritchard died in 1921 when the R38 airship exploded over the Humber estuary; his body was never found. Captain Alcock, just six months after his triumph and being knighted by George V, died at Rouen in Normandy in December 1919 when his new Vickers Viking crashed en route to the Paris air show.

Mark Steyn, “Come, Josephine, in My Flying Machine”, SteynOnline, 2019-07-07.

April 13, 2019

Canada and the Battle of the Atlantic, part 11 by Alex Funk

Editor’s Note: This series was originally published by Alex Funk on the TimeGhostArmy forums (original URL – https://community.timeghost.tv/t/canada-and-the-battle-of-the-atlantic-part-4/1447/3).

Sources:

- Far Distant Ships, Joseph Schull, ISBN 10 0773721606 (An official operational account published in 1950, somewhat sensationalist)

[Schull’s book was published in part because the funding for the official history team had been cut and they did not feel that the RCN’s contribution to the Battle of the Atlantic should have no official recognition. It is very much an artifact of its era, and needs to be read that way. A more balanced (and weighty) history didn’t appear until the publication of No Higher Purpose and A Blue Water Navy in 2002, parts 1 and 2 of the Official Operational History of the RCN in WW2, covering 1939-1943 and 1943-1945, respectively.]- North Atlantic Run: the Royal Canadian Navy and the battle for the convoys, Marc Milner, ISBN 10 0802025447 (Written in an attempt to give a more strategic view of Canada’s contribution than Schull’s work, published 1985)

- Reader’s Digest: The Canadians At War: Volumes 1 & 2 ISBN 10 0888501617 (A compilation of articles ranging from personal stories to overviews of Canadian involvement in a particular campaign. Contains excerpts from a number of more obscure Canadian books written after the war, published 1969)

- All photos used exist in the Public Domain and are from the National Archives of Canada, unless otherwise noted in the caption.

I have inserted occasional comments in [square brackets] and links to other sources that do not appear in the original posts. A few minor edits have also been made for clarity.

Earlier parts of this series:

Part 1 — Canada’s navy before WW2

Part 2 — The Admiralty takes control

Part 3 — The professionals and the amateurs

Part 4 — 1940: The fall of France, the battle begins, and the RCN dreams of expansion

Part 5 — The RCN’s desperate need for warships

Part 6 — New ships, new challenges

Part 8 — Expansion problems: not enough men for not enough ships

Part 9 — Early-to-mid 1941, The Rocky Isle in the Ocean

Part 10 — The Newfoundland Escort Force and the Canadian corvettes

Part 11 — “Chummy” Prentice and the NEF

One of the most colourful men to serve in the Newfoundland Escort Force was Commander J.D. Prentice. He had taken early retirement from the RN in 1934 and in 1939, at age 41, he returned to sea. Marc Milner outlines Prentice’s career in North Atlantic Run:

“Chummy” Prentice, as his friends called him, was one of the real characters of the war and a driving force behind the RCN’s quest for efficiency. Born in Victoria, BC, of British parents in 1899, Prentice had decided on a naval career by the tender age of thirteen. He wanted to join the infant RCN, but his father believed that the new naval service of Canada would become little more than another avenue for political patronage. If Prentice was to join the navy it had to be the RN, so in 1912 he entered the Royal Naval College, Dartmouth, and later in the same year joined the RN as a cadet. His twenty-two years of service in the RN were undistinguished, the pinnacle had been serving as first lieutenant commander of the battleship Rodney. When passed over for promotion to commander in 1934, Prentice realized that his future in the RN was limited, and he therefore took an early retirement. He returned to BC in 1937 to take a position as financial secretary of the Western Canada Ranching Company, and there he stayed until the outbreak of war in 1939.

The RN having no immediate employment for him, Prentice was placed on the list of officers at the disposal of the RCN. When the RCN mobilized, Prentice was offered a commission at his old RN rank, an offer he eagerly accepted, and he was posted to Sydney, Cape Breton, as staff officer to the Naval Officer in Charge. Although content with his lot, Prentice was rescued from this important but otherwise colourless duty in July 1940, when he was transferred to Halifax pending the commissioning of the corvette HMCS Lévis, which he was to command. In Halifax, Prentice came in contact with Commodore L.W. Murray, then Commodore Commanding Halifax Force, whom Prentice had first met at the RN’s staff college. The two men shared many ideas and interests, and became fast and lifelong friends. Prentice soon found himself attached to Murray’s staff as Senior Officer, Canadian Corvettes [the command of Lévis went to Lieutenant Charles Gilding, RCNR]. It was a curious post, one which never fit into the organizational structure of any command and soon became little more than titular. However, it did provide Prentice with a legitimate priority of interest in the affairs of the little ships, which he was to exercise consistently over the next three years.

Murray and Prentice were separated when Murray left for Britain to take command of Canadian vessels overseas through the summer of 1940, and Prentice spent the winter of 1940-41 working up the few Canadian corvettes had been launched before the freeze up. What was to become “The Dynamic Duo” of the east coast was not to be broken up for long. March 1941 saw Prentice finally given his first command, the corvette HMCS Chambly. Milner continues:

All of this gave his fertile and often over-active imagination an opportunity for expression, for Prentice was an innovator and an original thinker. During his service in the RN he had produced numerous papers and essays for publication and competitions on a myriad of topics. Not surprisingly, he quickly developed ideas of what corvettes were capable of, how they could be used, and how their efficiency could be improved.

As a fairly senior officer in a rather junior service, one in which he had no long-standing presence or long-term ambitions, Prentice allowed his concern for efficiency to dominate his work. His combination of experience, seniority, and lack of vested service interest gave Prentice a freedom of expression which few if any other RCN officers enjoyed. By all accounts he used his position and influence wisely. In any event, Murray was always interposed between Prentice and more senior (and, one might assume, less tolerant) officers and was therefore able to direct some of the heat generated by Prentice into more useful, if not always successful, directions. In many ways Prentice was Murray’s alter ego, an energetic innovator paired to an efficient but somewhat uninspired administrator.

Prentice’s eccentricities apparently did not keep him at arm’s length from his fellow officers. More importantly, perhaps, his cigars, monocle, English accent, and sense of fairness positively endeared him to the lower decks. The story of Chummy Prentice and the monocle is probably apocryphal, but it illustrates the type of rapport he apparently had with the other ranks. It is said that once a whole division of Chambly‘s company paraded wearing monocles. Without saying a word or altering his expression Prentice completed his rounds and then took a position in front of the jesting crewmen. After a moment’s pause, and while the whole crew waited for the dressing down, Prentice threw his head back, flinging his monocle into the air. As the glass fell back he caught it between his eyebrow and the bottom lid, exactly in the place from whence it had been ejected. “When you can do that,” Prentice is reputed to have said, “you can all wear monocles.” Whether it is a true story or not, it makes the point. Prentice was an ideal commanding officer and admirably suited for the posts which he held. He was ruthless in his quest for efficiency at all levels of shipboard life, from gunnery to the welfare of the lower decks. A good measure of fairness and a well-developed sense of propriety seem to have governed his treatment of subordinates. He was, above all, enthusiastic about his work, and much of this rubbed off on those who came in contact with him. Although the RN apparently felt he had little to offer them, Prentice clearly found his calling with the small ships of the RCN.

Commander J.D. Prentice, Commanding Officer, on the bridge of the corvette HMCS Chambly at sea, 24 May 1941.

Canada. Dept. of National Defence / Library and Archives Canada / PA-151743The first task assigned to Prentice and the embryonic NEF was screening the battle-cruiser Repulse as that great ship lay in Conception Bay following the hunt for the Bismarck. Screening Repulse was good basic exercise if nothing else, and the clear, unstratified waters of the bay returned good ASDIC echoes. The real work of NEF began shortly thereafter. Pending the arrival of a Canadian commanding officer for NEF, the escorts were placed under Captain C.M.R. Schwerdt, RN, the Naval Officer in Charge, St John’s (whose establishment had in fact only just been transferred to the RCN). Schwerdt, in consultation with his trade officers, determined that NEF should attempt its first escort of an eastbound convoy in early June. The date of sailing, course, and so on could all be obtained through local trade connections, and a rendezvous with HX-129 was worked out by Schwerdt’s staff. Word-of-mouth orders were passed to Prentice advising him of this plan and of the likelihood of very poor weather. The orders, which in effect stated “If you have any reasonable hope of joining the convoy, proceed to sea.” gave Prentice the carte blanche he thrived on; foul weather only added to the challenge.

Members of the ship’s company, HMCS Chambly, St. John’s, Newfoundland, May 1941.

Canada. Dept. of National Defence / Library and Archives Canada / PA-115351On 2 June, the first NEF escort group to sail on convoy duty put to sea. The escorts Chambly, Orillia, and Collingwood rendezvoused with HX-129 within an hour of their estimated position. Although the convoy was not attacked, many stragglers and independents nearby were lost to enemy action, and the Canadians soon found themselves busy with rescue work. Two ASDIC contacts were made, one each by Collingwood and Chambly while operating in company. Unfortunately, co-ordination of searches was hampered by the failure of visual-signaling (V/S) equipment in Chambly. The latter also had to stop engines twice to repair defects. Despite the breakdowns, lost opportunities, and general mayhem of this first operation, Prentice’s spirits were extremely buoyant. “The ships behaved extremely well,” he wrote in his report of proceedings. Certainly all the COs in question, Acting Lieutenant Commander W.E.S. Briggs, RCNR, of Orillia, and Acting Lieutenant Commander W. Woods, RCNR, of Collingwood, went on to do well in the RCN. But one cannot help but feel that Prentice was writing about the corvettes themselves.

The first operation of NEF pointed to the many problems which beset the expansion fleet, and yet Prentice was pleased with the group’s performance. Having participated directly in the commission and workup of these first seven RCN corvettes, the SO, Canadian Corvettes, could be excused his pride in their initial foray into troubled waters. Other RCN officers maintained similar limited expectations of the expansion fleet. The British, on the other hand, entertained little sympathy for struggling civilian sailors. From the outset, RCN and RN officers displayed a tendency to view the expansion fleet from vastly different perspectives. To use an analogy, the RCN was, through the period of 1941-43, like half a glass of water. From the Canadian perspective the glass was half full; the RN always considered it half empty. Though the Naval Staff was apparently informed of how ill-prepared the early corvettes really were, this came as a rude shock to the more staid RN. Moreover, shortcomings manifested themselves even before the first major Canadian convoy battle.

December 3, 2018

Viking Expansion – Wine Land – Extra History – #6

Extra Credits

Published on 1 Dec 2018From Greenland, explorers like Bjarni, Freydis, and Leif Erikson — aka “Leif the Lucky” — ventured into Vinland, the very first bit of North America sighted by Europeans. It was rich in natural resources, including the grapes (and thus wine) for which it received its title, but this set of expeditions would be very, very short-lived…

Join us on Patreon! http://bit.ly/EHPatreon

November 4, 2018

That pesky Supreme court ruling on the Churchill Falls deal

I use the term “pesky” in the headline to avoid being slagged by one or possibly even both of my Newfoundland and Labrador readers … to curry favour with them, I’d need to escalate from somewhere between “ethically doubtful” and “outrageous”, and even that might not capture the essence of anger and resentment at Quebec’s amazingly great deal long-term on cheap hydro-electric power from the Churchill Falls facility. It is, as Wikipedia says, “the second largest hydroelectric plant in North America, with an installed capacity of 5,428 MW”, and thanks to Quebec financing and astute negotiations, most of that output is sold to Quebec at a very small proportion of today’s open market price. Colby Cosh arches an eyebrow over a Supreme Court justice’s lone vote of dissent on the case:

It is my solemn duty to perform one of the important functions of a newspaper columnist: raising one questioning eyebrow. On Friday the Supreme Court issued a judgment in the long battle between Churchill Falls (Labrador) Corp., a subsidiary of Newfoundland and Labrador Hydro, and Hydro-Québec. CFLco is the legal owner of the notorious Churchill Falls Generating Station in the deep interior of Labrador, close to the border with Quebec.

The station was built between 1966 and 1971. Hydro-Québec provided backing when the financing proved difficult for the original owner, an energy exploration consortium called Brinco. This led to the signing of Canada’s most famous lopsided contract: a 1969 deal for Hydro-Québec to receive most of the plant’s output for the next 40 years at a quarter of a cent per kilowatt-hour, followed by 25 more years at one-fifth of a cent. The bargain ends in 2041, at which time CFLco will get full use and disposal of the station’s electricity back.

This has been a heck of a deal for Quebec. It took on the risk of financing and building the station in exchange for receiving the electricity at a low fixed price — one that both sides in the court case agree was reasonable at the time. But it meant that Newfoundland saw no benefit from decades of oil price shocks, from the end of nuke-plant construction in the U.S., or from the increasing market advantage hydroelectricity enjoys while dirtier forms of power generation attract eco-taxation.

It has been maddening for Newfoundland to remain poor while Hydro-Québec grows fat on the profits from a Newfoundland river. Quebec, for its part, has never been completely convinced of the legitimacy of its border with Labrador, and it sees its good fortune as a sort of angelic reward for having to be part of Confederation. The Churchill Falls deal is (quite reasonably) regarded as proof that Quebec’s homegrown industrialists were able to beat resource-exploiting Anglo financiers at their own game. There are thus reasons beyond the bottom line that Quebec has never wanted to renegotiate the Churchill Falls contract. But the bottom line is enough.

October 18, 2018

Canada legalizes cannabis … then takes the rest of the week off

What do you know? Justin Trudeau actually followed through on his promise to legalize marijuana across the country! Of all his election promises, that’s probably the one that most voters expected him to ditch as soon as the votes were counted, yet here we are in the second country in the world to legalize the stuff. So, everyone not here in Canuckistan, we’ll probably be back sometime next week as we’ve got a lot of mellowing to get done…

Oh, you want a blog post? Duuuude, just take another hit.

Oh, okay, here ya go:

An Abacus Data poll released this week suggests Canadians are ready for marijuana legalization even if their governments might not be: Strong majorities of respondents in every age group and in every region said they could support or at least “accept” the framework that goes into effect Oct. 17. Even 54 per cent of Conservative voters said they could support or accept legal weed.

[…]

The resistance continues, certainly. In a special meeting on Tuesday, just days before Ontario’s municipal elections, City Council in Markham, Ont., passed a bylaw restricting marijuana smoking to private residences. It had earlier voted 12-1 in favour of “opting out” of storefront retail, as allowed for under provincial regulations.

“When you’re taking your grandmother down the street for a walk, (we don’t want you) having to be exposed to a number of individuals potentially at a street corner participating in it,” says Mayor Frank Scarpitti.

Richmond, B.C., is another refusenik jurisdiction. Mayor Malcolm Brodie notes the city took a much harsher approach than neighbouring Vancouver to the proliferation of illegal dispensaries, throwing the book at the only one that attempted to open. And he credits the provincial government with listening to municipalities’ concerns and allowing them to go their own ways

Indeed, considering the Reefer Madness-level debate, it seems somewhat remarkable how peacefully this sea change is washing over the country — and it seems the patchwork of provincial and municipal rules, much derided by Conservatives, is partly to credit for that.

A quick run-down of the new rules.

Thanks to time zones, the first legal sale of marijuana happened in Newfoundland:

One of the first customers to buy legal recreational cannabis in Canada says he has no intention of smoking, vaping or otherwise consuming the gram of weed he bought at a store in St. John’s.

Ian Power, who was first in line at one of several stores in the country’s easternmost province that opened just after midnight local time, says he plans to frame his purchase.

Hundreds of customers were lined up around the block at the private store on Water Street, the main commercial drag in the Newfoundland and Labrador capital, by the time the clock struck midnight.

A festive atmosphere broke out, with some customers lighting up on the sidewalk and motorists honking their horns in support as they drove by the crowd.

Cannabis NL expected 22 stores to open on Oct. 17, but not all opted to open in the middle of the night to commemorate the event.

Licensed marijuana producer Canopy Growth Corp. opened the Tweed-branded store in St. John’s at the late hour, while retailer Loblaw Companies Ltd. planned to start selling cannabis at its 10 locations at 9 a.m.

July 2, 2018

Mark Steyn on 49th Parallel

His annual Canada Day post this year featured a World War 2 British film about Canada intended for Americans:

The film stars, in order of billing, Leslie Howard, Laurence Olivier, Raymond Massey, Anton Walbrook, Eric Portman “and the music of Ralph Vaughan Williams”, which gets an above-the-title credit – as well it should. Vaughan Williams’ score is an integral part of the picture and, if not especially Canadian (save for a very short evocation of Calixa Lavallée’s “O Canada” right at the beginning), accompanies the country’s physical landscape beautifully, particularly in the opening travelogue, mostly shot by Freddie Young leaning out of a plane with a hand-held camera and edited back in England by David Lean. (Lean and Young, of course, subsequently worked together on Lawrence of Arabia, Doctor Zhivago and Ryan’s Daughter.) And, if you’re thinking that (with one exception) none of these participants seems terribly Canuck, well, if it’s any consolation, the English also get to play all the Nazis, too. The Canadians are largely relegated to small roles and extras – like the real seamen who play the survivors of the Canadian ship torpedoed in the Gulf of St Lawrence at the opening of the picture. “So,” pronounces the German U-boat commander, “the curtain rises on Canada.”

U-37 decides to flee to Hudson’s Bay to evade the RCAF and RCN patrols looking for it. Six Germans are put ashore to scout for supplies. But, even as they set foot on land, they hear the swoop of planes and look back to see Canadian bombers destroying their submarine. In order to lend verisimilitude to the scene, Michael Powell destroyed a real – or real-ish – sub, built for him in Halifax, Nova Scotia. The RCAF gave him two thousand-pound bombs to make it look good, and he put them on “U-37” and was cunning enough to neglect to tell the actors, lest it made them nervous. The sub was then towed to the Strait of Belle Isle between Labrador and Newfoundland to be blown sky high. That was Powell’s only mistake. Notwithstanding that he named the film after Canada’s southern border, the director’s grip on the country’s eastern border was a little hazier. He had forgotten that Newfoundland was not (yet) in Canada but was a British possession in its own right. So HM Customs impounded “U-37” and Powell had to go directly to the Governor to get it back.

Other than that, he and Pressburger didn’t put a foot wrong. The location footage was impressive in its day, and still striking in ours; Pressburger’s script is subtle and humane; and the episodic structure allows for plenty of variety. Following the loss of U-37, the six Germans are now beached in northern Canada and have to figure out a way to get to safe, neutral America. They make their way to a Hudson’s Bay trading post, where the factor (played by the great Scots actor Finlay Currie) is welcoming back an old friend who’s spent the last eleven months hunting in the wilds and so has no idea Canada is at war. Johnny is a French-Canadian trapper played by – who else? – Laurence Olivier. We first meet him in the bath tub singing “Alouette”, and, as often with Olivier, the attention to detail on the accent is so good that it becomes oddly intrusive: “Diss is one big country, but verra few pipple. Ever-wan know ever-body. You can’t make goosestep trew it widdout da police fine out,” he tells the senior German officer (Eric Portman).

The window shot Michael Powell uses to get the Nazis into the factor’s small cabin is cool and clinical and all the more chilling for it. The six Germans enter and announce that they’re now in control. When you’ve just come in off the tundra after eleven months and you want to have a soak in the tub and unwind, the Master Race showing up is a bit of a downer. “Okay, you are German. Why yell about it? I am Canadian,” says the Frenchie. “He is Canadian” – he points to the Scots factor – “and he is Canadian” – and to the smiling eskimo lad: French, English and Inuit all with the same unhyphenated label “Canadian”. That’s a lot simpler than the fractious diversity at Parliament Hill earlier today.

The Nazi lieutenant attempts to beguile his captives with a copy of Mein Kampf, but Trapper Johnny isn’t interested. “What’s the matter with Negroes?” he asks.

“They’re semi-apes,” explains the German. “One step above the Jews.” This is something of a remote concern at a Hudson’s Bay trading post. The Nazis seems as enraged by their prisoners’ geniality as by anything else. As they depart, one tears a portrait of the King and Queen off the wall and carves a swastika into the space.

Pressburger’s plot follows as you’d expect: There are six Germans, and soon there will be five, and then four, three, two… From Hudson’s Bay, they commandeer a seaplane that crashes near a Hutterite community in Manitoba, where a young pre-Mary Poppins Glynis Johns is sweetly trusting of them. They make their way to Indian Day in Banff National Park, for a rather Hitchcockian scene, and thence to a camp in the Rockies, where an arty pacifist (Leslie Howard) is discoursing on Thomas Mann. The tone is set by Olivier’s Frenchie coming in from the bush: He may not be interested in war, and nor is Glynis Johns or Leslie Howard. But war is interested in them. This was the purpose of the film, as the British Ministry of Information saw it: That’s why they wanted it set in Canada, rather than in, say, England, across the Channel from Occupied Europe. These trappers, Hutterites, and pacifists didn’t come looking for trouble. But, even five thousand miles from the fighting, trouble came looking for them – in big, empty, peaceable Canada. And the implicit message to America was: In the end, it will come for you, too. There is no 49th Parallel. Whichever side of it you’re on, it’s the same side.

July 5, 2017

The BBC visits L’Anse Aux Meadows

Allan Lynch visits L’Anse Aux Meadows National Historic Site in Newfoundland, in search of Viking history:

It is here, on the northern tip of Newfoundland, that a significant moment in human migration and exploration took place.

In the year 1000, nearly 500 years before Christopher Columbus set sail, a Viking longboat, skippered by Leif Erikson, brought 90 men and women from Iceland to establish a new settlement – the first European settlement in the New World.

Erikson’s party arrived at low tide and found themselves stranded in the misty shallows of Epaves Bay. When the tide returned, they moved further inland, navigating up Black Duck Brook to the place where they would establish their stronghold in their new-found land.

By modern sensibilities, L’Anse Aux Meadows can seem a harsh place, with fierce coastal winds whipping across the remote landscape. But for people who just travelled across the unforgiving North Atlantic in open boats, it was perfect. The forests were rich in game; the rivers teemed with salmon larger than the Norse had ever seen; the grasslands provided a bounty of food for livestock; and, in some places, wild grapes grew, prompting the Vikings to name this land ‘Vinland’.

The settlement didn’t last long, however; the community abandoned the settlement after less than a decade after repeated clashes with the island’s native tribes, known to the Vikings as ‘Skraelings’.

For more than 100 years, archaeologists in Finland, Denmark and Norway used ancient Norse sagas to guide their search for Erikson’s lost settlement, scouring the coast of North America from Rhode Island to Labrador.

The site remained undiscovered until 1960 when a husband-and-wife team of Norwegian archaeologists, Helge and Anne Stine Ingstad, heard from locals of L’Anse Aux Meadows – the town for which the site was named – speak of what they believed to be an old Indian camp. The initial excavation of the site’s mysterious seaside mounds revealed a layout similar to longhouses found in confirmed Viking settlements in Iceland and Greenland. Then, the discovery of a 1,000-year-old nail indicated that ship building had taken place here.

“As kids we played on the curious mounds,” said Clayton Colbourne, a former Parks Canada guide at L’Anse Aux Meadows. “We didn’t know anything about the Vikings being here.”

H/T to Never Yet Melted for the link.

July 9, 2016

The Battle of the Somme – Brusilov On His Own I THE GREAT WAR – Week 102

Published on 7 Jul 2016

Check out Epic History TV’s video about the first day of the Somme: http://bit.ly/SommeEpicTV

After months of preparations and a week long artillery bombardment, the Battle of the Somme is unleashed on the Western Front. The great British and French offensive, brainchild of General Sir Douglas Haig, which is supposed to crush the Germans on the Western Front once and for all. But the initial infantry attack is a disaster. And on the Eastern Front, General Alexei Brusilov realises that his northern flank support is not worth the name.

June 20, 2016

Getting to L’Anse Aux Meadows

A few days back, “Weirddave” posted a little account of his recent visit to L’Anse Aux Meadows:

You can fly into Gander, but it’s expensive AF and you’ll have to make a jillion connections and live in airports for 2 days. Driving from the US means taking I-95 as far as it goes, then transiting New Brunswick and Nova Scotia to North Sydney. There you get on a ferry for an 8 hour trip to Port Aux Basque. Do it overnight and splurge for a cabin (trust me on this). Even then, you can’t get into Port Aux Basque if it’s too windy (a not uncommon occurrence in the North Atlantic). Our ferry sailed in a circle off Port Aux Basque for 12 hours until it was calm enough to go in, costing us a whole day (you don’t drive at night in Newfoundland because the island is infested with moose and you’ll hit one). There is no WiFi on the ferry.

From Port Aux Basque it’s 699 kilometers to L’Anse Aux Meadow, 699 kilometers of 2 lane highway with lots of potholes. If you love scrub pine and birch, you’ll be in heaven. It’s very pretty, and Gros Morne National Park, which you’ll go through about halfway, is gorgeous. The drive is miserable when it’s raining, and it’s always raining in Newfoundland. As a bonus it was 2 degrees C today. After you’ve seen L’Anse Aux Meadow ( a day at most ) you have to do it all over again going the other way. The local hootch is a rum called Screech that aspires to be Val-U-Rite. On the plus side, the locals are friendly, if occasionally unintelligible, and I ate 6 lobsters in four days, so yum.

If you find yourself in Newfoundland, you must go to L’Anse Aux Meadow. If you’re thinking of going, my advice would be to take an RV and make it a leisurely trip across the Maritimes. Take 2 weeks off and really enjoy yourself.

May 26, 2015

Canada in World War 1 I THE GREAT WAR Special

Published on 25 May 2015

One of the countries that found its identity in the trenches of World War 1 was Canada. During the 2nd Battle of Ypres and the Battle of Vimy Ridge the Canadians and Newfoundlanders proofed their worthiness over and over again. Indy takes a special look on Canada in World War 1 and how they became one one of the feared enemies of the Germans.