Now I should note that the initial response in Italy to the shocking appearance of effective siege artillery was not to immediately devise an almost entirely new system of fortifications from first principles, but rather – as you might imagine – to hastily retrofit old fortresses. But […] we’re going to focus on the eventual new system of fortresses which emerge, with the first mature examples appearing around the first decades of the 1500s in Italy. This system of European gunpowder fort that spreads throughout much of Europe and into the by-this-point expanding European imperial holdings abroad (albeit more unevenly there) goes by a few names: “bastion” fort (functional, for reasons we’ll get to in a moment), “star fort” (marvelously descriptive), and the trace italienne or “the Italian line”. since that was where it was from.

Since the goal remains preventing an enemy from entering a place, be that a city or a fortress, the first step has to be to develop a wall that can’t simply be demolished by artillery in a good afternoon or two. The solution that is come upon ends up looking a lot like those Chinese rammed earth walls: earthworks are very good at absorbing the impact of cannon balls (which, remember, are at this point just that: stone and metal balls; they do not explode yet): small air pockets absorb some of the energy of impact and dirt doesn’t shatter, it just displaces (and not very far: again, no high explosive shells, so nothing to blow up the earthwork). Facing an earthwork mound with stonework lets the earth absorb the impacts while giving your wall a good, climb-resistant face.

So you have your form: a stonework or brick-faced wall that is backed up by essentially a thick earthen berm like the Roman agger. Now you want to make sure incoming cannon balls aren’t striking it dead on: you want to literally play the angles. Inclining the wall slightly makes its construction easier and the end result more stable (because earthworks tend not to stand straight up) and gives you an non-perpendicular angle of impact from cannon when they’re firing at very short range (and thus at very low trajectory), which is when they are most dangerous since that’s when they’ll have the most energy in impact. Ideally, you’ll want more angles than this, but we’ll get to that in a moment.

Because we now have a problem: escalade. Remember escalade?

Earthworks need to be wide at the base to support a meaningful amount of height, tall-and-thin isn’t an option. Which means that in building these cannon resistant walls, for a given amount of labor and resources and a given wall circuit, we’re going to end up with substantially lower walls. We can enhance their relative height with a ditch several out in front (and we will), but that doesn’t change the fact that our walls are lower and also that they now incline backwards slightly, which makes them easier to scale or get ladders on. But obviously we can’t achieved much if we’ve rendered our walls safe from bombardment only to have them taken by escalade. We need some way to stop people just climbing over the wall.

The solution here is firepower. Whereas a castle was designed under the assumption the enemy would reach the foot of the wall (and then have their escalade defeated), if our defenders can develop enough fire, both against approaching enemies and also against any enemy that reaches the wall, they can prohibit escalade. And good news: gunpowder has, by this point, delivered much more lethal anti-personnel weapons, in the form of lighter cannon but also in the form of muskets and arquebuses. At close range, those weapons were powerful enough to defeat any shield or armor a man could carry, meaning that enemies at close range trying to approach the wall, set up ladders and scale would be extremely vulnerable: in practice, if you could get enough muskets and small cannon firing at them, they wouldn’t even be able to make the attempt.

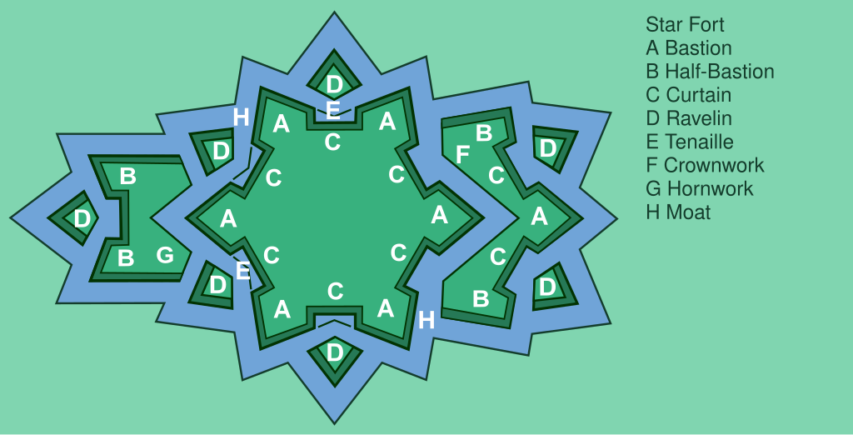

But the old projecting tower of the castle, you will recall, was designed to allow only a handful of defenders fire down any given section of wall; we still want that good enfilade fire effect, but we need a lot more space to get enough muskets up there to develop that fire. The solution: the bastion. A bastion was an often diamond or triangular-shaped projection from the wall of the fort, which provided a longer stretch of protected wall which could fire down the length of the curtain wall. It consists of two “flanks” which meet the curtain wall and are perpendicular to it, allowing fire along the wall; the “faces” (also two) then face outward, away from the fort to direct fire at distant besiegers. When places at the corners of forts, this setup tends to produce outward-spiked diamonds, while a bastion set along a flat face of curtain wall tends to resemble an irregular pentagon (“home plate”) shape [Wiki]. The added benefit for these angles? From the enemy siege lines, they present an oblique profile to enemy artillery, making the bastions quite hard to batter down with cannon, since shots will tend to ricochet off of the slanted line.

In the simplest trace italienne forts [Wiki], this is all you will need: four or five thick-and-low curtain walls to make the shape, plus a bastion at each corner (also thick-and-low, sometimes hollow, sometimes all at the height of the wall-walk), with a dry moat (read: big ditch) running the perimeter to slow down attackers, increase the effective height of the wall and shield the base of the curtain wall from artillery fire.

But why stay simple, there’s so much more we can do! First of all, our enemy, we assume, have cannon. Probably lots of cannon. And while our walls are now cannon resistant, they’re not cannon immune; pound on them long enough and there will be a breach. Of course collapsing a bastion is both hard (because it is angled) and doesn’t produce a breach, but the curtain walls both have to run perpendicular to the enemy’s firing position (because they have to enclose something) and if breached will allow access to the fort. We have to protect them! Of course one option is to protect them with fire, which is why our bastions have faces; note above how while the flanks of the bastions are designed for small arms, the faces are built with cannon in mind: this is for counter-battery fire against a besieger, to silence his cannon and protect the curtain wall. But our besieger wouldn’t be here if they didn’t think they could decisively outshoot our defensive guns.

But we can protect the curtain further, and further complicate the attack with outworks [Wiki], effectively little mini-bastions projecting off of the main wall which both provide advanced firing positions (which do not provide access to the fort and so which can be safely abandoned if necessary) and physically obstruct the curtain wall itself from enemy fire. The most basic of these was a ravelin (also called a “demi-lune”), which was essentially a “flying” bastion – a triangular earthwork set out from the walls. Ravelins are almost always hollow (that is, the walls only face away from the fort), so that if attackers were to seize a ravelin, they’d have no cover from fire coming from the main bastions and the curtain wall.

And now, unlike the Modern Major-General, you know what is meant by a ravelin … but are you still, in matters vegetable, animal and mineral, the very model of a modern Major-General?

But we can take this even further (can you tell I just love these damn forts?). A big part of our defense is developing fire from our bastions with our own cannon to force back enemy artillery. But our bastions are potentially vulnerable themselves; our ravelins cover their flanks, but the bastion faces could be battered down. We need some way to prevent the enemy from aiming effective fire at the base of our bastion. The solution? A crownwork. Essentially a super-ravelin, the crownwork contains a full bastion at its center (but lower than our main bastion, so we can fire over it), along with two half-bastions (called, wait for it, “demi-bastions”) to provide a ton of enfilade fire along the curtain wall, physically shielding our bastion from fire and giving us a forward fighting position we can use to protect our big guns up in the bastion. A smaller version of the crownwork, called a hornwork can also be used: this is just the two half-bastions with the full bastion removed, often used to shield ravelins (so you have a hornwork shielding a ravelin shielding the curtain wall shielding the fort). For good measure, we can connect these outworks to the main fort with removable little wooden bridges so we can easily move from the main fort out to the outworks, but if the enemy takes an outwork, we can quickly cut it off and – because the outworks are all made hollow – shoot down the attackers who cannot take cover within the hollow shape.

An ideal form of a bastion fortress to show each kind of common work and outwork.

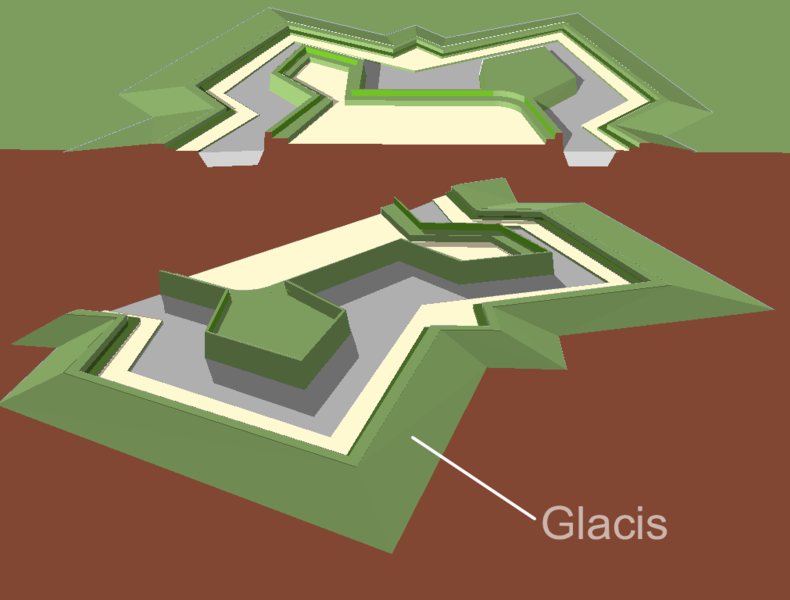

Drawing by Francis Lima via Wikimedia Commons.We can also do some work with the moat. By adding an earthwork directly in front of it, which arcs slightly uphill, called a glacis, we can both put the enemy at an angle where shots from our wall will run parallel to the ground, thus exposing the attackers further as they advance, and create a position for our own troops to come out of the fort and fire from further forward, by having them crouch in the moat behind the glacis. Indeed, having prepared, covered forward positions (which are designed to be entirely open to the fort) for firing from at defenders is extremely handy, so we could even put such firing positions – set up in these same, carefully mathematically calculated angle shapes, but much lower to the ground – out in front of the glacis; these get all sorts of names: a counterguard or couvreface if they’re a simple triangle-shape, a redan if they have something closer to a shallow bastion shape, and a flèche if they have a sharper, more pronounced face. Thus as an enemy advances, defending skirmishers can first fire from the redans and flèches, before falling back to fire from the glacis while the main garrison fires over their heads into the enemy from the bastions and outworks themselves.

A diagram showing a glacis supporting a pair of bastions, one hollow, one not.

Diagram by Arch via Wikimedia Commons.At the same time, a bastion fortress complex might connect multiple complete circuits. In some cases, an entire bastion fort might be placed within the first, merely elevated above it (the term for this is a “cavalier“) so that both could fire, one over the other. Alternately, when entire cities were enclosed in these fortification systems (and that was common along the fracture zones between the emerging European great powers), something as large as a city might require an extensive fortress system, with bastions and outworks running the whole perimeter of the city, sometimes with nearly complete bastion fortresses placed within the network as citadels.

Fort Saint-Nicolas, which dominates the Old Port of Marseille. The fort forms part of a system with the low outwork you see here and also an older refitted castle, Fort Saint-Jean, on the other side of the harbor.

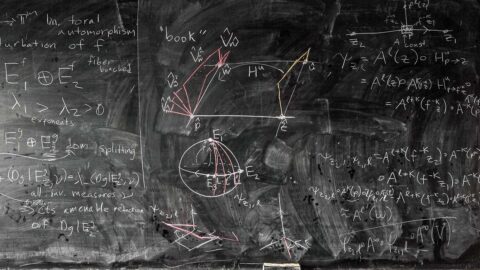

Photo via Wikimedia Commons.All of this geometry needed to be carefully laid out to ensure that all lines of approach were covered with as much fire as possible and that there were no blindspots along the wall. That in turn meant that the designers of these fortresses needed to be careful with their layout: the spacing, angles and lines all needed to be right, which required quite a lot of math and geometry to manage. Combined with the increasing importance of ballistics for calculating artillery trajectories, this led to an increasing emphasis on mathematics in the “science of warfare”, to the point that some military theorists began to argue (particularly as one pushes into the Enlightenment with its emphasis on the power of reason, logic and empirical investigation to answer all questions) that military affairs could be reduced to pure calculation, a “hard science” as it were, a point which Clausewitz (drink!) goes out of his way to dismiss (as does Ardant du Picq in Battle Studies, but at substantially greater length). But it isn’t hard to see how, in the heady centuries between 1500 and 1800 how the rapid way that science had revolutionized war and reduced activities once governed by tradition and habit to exercises in geometry, one might look forward and assume that trend would continue until the whole affair of war could be reduced to a set of theorems and postulates. It cannot be, of course – the problem is the human element (though the military training of those centuries worked hard to try to turn men into “mechanical soldiers” who could be expected to perform their role with the same neat mathmatical precision of a trace italienne ravelin). Nevertheless this tension – between the science of war and its art – was not new (it dates back at least as far as Hellenistic military manuals) nor is it yet settled.

An aerial view of the Bourtange Fortress in Groningen, Netherlands. Built in 1593, the fort has been restored to its 1750s configuration, seen here.

Photo by Dack9 via Wikimedia Commons.But coming back to our fancy forts, of course such fortresses required larger and larger garrisons to fire all of the muskets and cannon that their firepower oriented defense plans required. Fortunately for the fortress designers, state capacity in Europe was rising rapidly and so larger and larger armies were ready to hand. That causes all sorts of other knock on effects we’re not directly concerned with here (but see the bibliography at the top). For us, the more immediate problem is, well, now we’ve built one of these things … how on earth does one besiege it?

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Fortification, Part IV: French Guns and Italian Lines”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2021-12-17.

November 28, 2024

QotD: The trace italienne in fortification design

October 13, 2024

The Soviet Union’s surplus of math nerds

The most recent review from Mr. and Mrs. Psmith’s Bookshelf is John Psmith’s musings on Math from Three to Seven: The Story of a Mathematical Circle for Preschoolers by Alexander Zvonkin, and he starts by talking about something the Soviets did better than the west:

To me, one of the greatest historical puzzles is why the Cold War was even a contest. Consider it a mirror image of the Needham Question: Joseph Needham famously wondered why it was that, despite having a vastly larger population and GDP, Imperial China nevertheless lost out scientifically to the West. (I examined this question at some length in this review.) Well, with the Soviets it all went in the opposite direction: they had a smaller population, a worse starting industrial base, a lower GDP, and a vastly less efficient economic system. How, then, did they maintain military and technological parity1 with the United States for so long?

The puzzle was partly solved for me, but partly deepened, when those of us who grew up in the ‘90s and ‘00s encountered the vast wave of former Soviet émigrés that washed up in the United States after the fall of communism. Anybody who played competitive chess back then, or who participated in math competitions, knows what I’m talking about: the sinking feeling you got upon seeing that your opponent had a Russian name. These days, the same scenes are dominated by Chinese and Indian kids. But China and India have large populations — the Russians were punching way above their weight, demographically speaking. Today, those same Russians are all over Wall Street and Silicon Valley and Ivy League math departments, still overrepresented in technical fields. What explains it? Are Russians just naturally better at math and physics?

When I related these questions to an Ashkenazi-supremacist friend of mine, he immediately suggested that “maybe it’s because they’re all Jewish”. (I’ve noticed that the most philosemitic people and the most antisemitic people sometimes have curiously similar models of the world, they just disagree on whether it’s a good thing.) My friend’s question wasn’t crazy, since there are definitely times when asking “were they all Jewish?” yields an affirmative answer. But in this case I had to disappoint him with the knowledge that many of these Russian math and chess superstars were gentiles.2 What’s more, by the ’60s and ’70s the Soviets had an entire discriminatory apparatus dedicated to keeping Jews out of the scientific establishment, so it would be impressive indeed if they were the foundation of its success.

Another possible explanation actually hinges on the relative poverty of the Soviet Union. Assume there are a lot of people out there with natural mathematical talent, but who given their druthers would major in underwater basket-weaving instead. The United States, because it’s so wealthy, can afford to “waste” a huge proportion of our talented population on humanities, arts, and other stuff that doesn’t involve you sitting in the school library until 3am. In other words, not going into a technical field is a form of luxury, which America can afford to consume. The Soviets, rather like the Chinese today, were forced by their underdog status to allocate human capital more efficiently (and had the authoritarian means to do so by force if necessary). This theory is related to the curious fact that, on average, the more feminist your society, the fewer women there are in math and science — which makes total sense if you assume that on average women are good at math but uninterested in it.

The thing is, the émigré superstars I encountered didn’t seem at all grudging or resentful about their studies. If anything it was the opposite. I’ve previously complained about how much I hate Russian mathematician Edward Frenkel’s3 book, but one thing it gets across well is just how important passion is to being a great mathematician, and passion was the thing the émigrés seemed to have a surfeit of. In college, the joke was that seminars by American professors would last an hour, whereas seminars by Russian professors would turn into boisterous debates lasting all night. People have been writing for centuries about Russians having a tendency towards “maximalism” — whether aesthetic or ideological or anything else. Maybe a culture-wide commitment to not doing anything by half-measures explains it?

1. There are scientific sub-disciplines where even at the end the Soviets had a clear lead, including several fields of math. Even crazier, there are sub-disciplines where we have not yet gotten back to where the Soviets were (for instance phage therapy).

2. Undeterred, my friend pointed out that many modern Russian gentiles have significant Jewish ancestry. The Soviets actively promoted mixed marriages, to the point where in some cities the average urban gentile Russian is as much as 25% Jewish. I still don’t think this explains Soviet scientific prowess, but it’s an interesting data point because the most highly urbanized areas are the ones where most of the mathematicians (and most of the émigrés) came from.

3. Before you ask, I looked it up and Frenkel is half Jewish, half gentile. I will leave it to you whether you count that as evidence for or against my friend’s theory.

April 18, 2024

“… the scary part of town, the place where the true freaks and degenerates hang out, is general topology“

John Psmith does his level best to make mathematics interesting to layfolk like you’n’me:

In our end of year post I threatened to write more math reviews, and multiple people in the comments egged me on. So now, with Jane laid up in the final stages of pregnancy, I have seized control of the Substack for a very special lightning round of math textbooks I recently enjoyed. No, wait! Don’t close the tab! I promise that some of these will be fun for non-mathematicians as well.

- Counterexamples in Topology, by Lynn Arthur Steen and J. Arthur Seebach Jr.

The mathematicians I have known included some eccentric characters. In fact when one considers research mathematicians as a class, it’s usually the normal people who are the exception. But there are degrees of weirdness. One of the most delightful things about the world is how fractal it is, and this extends to human hierarchies. Take any unusual group of people — frequent-flyers, monastics, the ultra-wealthy, members of genealogical societies — and zoom in on them, and it turns out there are even stranger or more elite subgroups buried within. This is true of mathematicians too, each subfield has its reputation, some of them regarded with awe, others with disdain. But ask any mathematician, “Who are the real weirdos? Who are the ones who are truly cracked?” The answer will be unanimous: it’s the topologists.

Topology is the study of spaces in the most abstract sense, so abstract that they may not even support a well-defined notion of distance (if your spaces are guaranteed to have distances, then you are now doing geometry rather than topology). Topology takes a coarser view of space: forget about curvature, distance, or really anything involving numbers at all. To a topologist, two points can be “near” each other or not, “connected” or not, and beyond that it doesn’t matter. This is the source of all the jokes about topologists mistaking donuts for coffee cups,1 but the kind of topology that studies multi-holed donuts, algebraic topology, is actually comparatively tame and normal. Also relatively normal is differential topology, which is the next neighborhood over from differential geometry, and which produces cool videos like this.

No, the scary part of town, the place where the true freaks and degenerates hang out, is general topology. General topology is where we go to figure out the basic definitions and frameworks that underlie the rest of topology. It’s about exploring what nearness and connectedness even are, and when mathematicians are trying to figure out what things are, that usually means probing the outer limits of what they can be. So general topology turns into the study of the most bizarre and deformed and disturbing spaces accessible to human cognition. No wonder its practitioners are a little weird.

Which brings me to this book, whose perversity is laid out right there in the title. It’s a big book of counterexamples to statements which seem obviously, intuitively correct. In general topology, things that seem intuitively correct are usually wrong:2 the field is notorious for proofs that almost work but twist out of your grasp at the last moment. A big book of counterexamples is exactly what you want for understanding why your proof that “all Xs are Ys and all Ys are Xs” falls flat. Seeing the logic fail is one thing, but seeing a concrete example of an X that is not a Y (or vice versa) brings it home with a satisfying finality.

But the real reason I love this book is the names, oh, the names. Let me flip through the table of contents with you: are “the Infinite Cage” and “the Wheel Without Its Hub” examples of topological spaces, or planes of the underworld? Are “Cantor’s Leaky Tent” and “Tychonoff’s Corkscrew” important counterexamples, or Level 2 wizard spells? I could spend hours idly leafing through this book, pondering these twisted and prosperous spaces, imagining them as worlds in themselves, imagining the bizarre sorts of creatures that might live there. Is this a math textbook or an RPG sourcebook? Trick question, they’re the same thing.

1. One of the proudest moments of my mathematical career was when I attended a faculty tea and a distinguished topologist asked me for a donut and I handed him a cup of coffee instead. Everybody lost it. Alas, I turned out to be much worse at math than I am at improvisational comedy, and my mathematical career ended shortly afterwards.

2. This is why we have the “separation axioms“. Every rung on that latter is the “well, actually …” to something that seems self-evident but isn’t.

February 6, 2024

Greek History and Civilisation, Part 1 – What Makes the Greeks Special?

seangabb

Published Feb 1, 2024This first lecture in the course makes a case for the Greeks as the exceptional people of the Ancient World. They were not saints: they were at least as willing as anyone else to engage in aggressive wars, enslavement, and sometimes human sacrifice. At the same time, working without any strong outside inspiration, they provided at least the foundations for the science, mathematics, philosophy, art and secular literature of later peoples.

(more…)

December 22, 2023

QotD: Mathematically inclined people

I’ve often said that mathematically inclined people generally get that way because God takes everything in their skulls and pushes it over to the left. Tensor calculus? No problem. Understanding that it’s disturbing for a grown man to speak Klingon? Sorry, the part of the brain that ordinarily handles that is busy thinking about the Pauli Exclusion Principle.

Steve H., “Star Wars Still Sucks: ‘Quick, Someone Put More Minwax on Natalie'”, Hog on Ice, 2005-05-26.

July 3, 2023

Schools fail their students when they try to teach things the students have no interest in learning

David Friedman has several examples of success in learning when the learner suddenly wants to learn the material:

One of the problems with our educational system is that it tries to teach people things that they have no interest in learning. There is a better way.

What started me thinking about the issue and persuaded me to write this post was an online essay, by a woman I know, describing how she used D&D to cure her math phobia.

How to Cure Mathphobia

I was failed by the education system, fell behind, never caught up, and was left with a panic response to the thought of interacting with any expression that has numbers and letters where I couldn’t immediately see what all of the numbers and letters were doing. The first time I took algebra one, I developed such a strong panic response that it wrapped around to the immediate need to go to sleep, like my brain had come up with a brilliant defense mechanism that left me with something akin to situational narcolepsy. (I did, actually, fall asleep in class several times, which had never happened to me before.) I retook the class the next year. I spent a lot of that year in tears, with a teacher who specifically refused to answer questions that weren’t more specific than “I don’t get it” or “I have no idea what any of those symbols mean or what we’re doing with them”.

Until she had a use for it:

The first time I played D&D, I was a high school student. My party was, incidentally, all female, apart from one girl’s boyfriend and the GM, who was the father of three of the players. We actually started out playing first edition AD&D, which I am almost tempted to recommend to beginners, just on the grounds that if you start there you will appreciate virtually every other edition of D&D you end up playing by comparison. I might have given up myself before I started, except that one of the players in the first game I ever spectated was a seven-year-old girl, and I was not about to claim that I couldn’t do something that a seven-year-old was handling just fine.

One of my most vivid memories of this group is the time we were on a massive zigzagging staircase — like one of those paths they have at the Grand Canyon, that zigzag back and forth down the cliff face so that anyone can reach the bottom without advanced rock-climbing. We saw a bunch of monsters coming for us from the ground below, and we weren’t sure whether they had climb speeds, but we didn’t super want to wait to find out. The ranger pulled out her bow to attack them before they could get to us.

“Now, wait a moment,” says the GM. “Can your arrows actually reach that far?”

“Well, they’re only, like, sixty feet away.”

“No, it’s more than that, because you have to think about height in addition to horizontal distance.”

“Yeah, but that’s, like, complicated?”

“Is it? Most of you are taking geometry right now, don’t you know how to find the hypotenuse of a right triangle?”

There were some groans. Math was hard. But we did know how to find the hypotenuse of a right triangle. We got out some scrap paper and puzzled over it for a couple minutes, volunteering the height of the cliff and the distance of the monsters and deciding that we could ignore the slight slope caused by the zigzagging stairways. We got a number back and compared it to the bow’s range per the rules. We determined that we could hit the monsters without a range penalty.

We killed the monsters. This wasn’t the real victory that day.

April 28, 2023

Use and misuse of the term “regression to the mean”

I still follow my favourite pro football team, the Minnesota Vikings, and last year they hired a new General Manager who was unlike the previous GM in that not only was he a big believer in analytics, he actually had worked in the analytics area for years before moving into an executive position. The first NFL draft under the new GM and head coach was much more in line with what the public analytics fans wanted — although the result on the field is still undetermined as only one player in that draft class got significant playing time. Freddie deBoer is a fan of analytics, but he wants to help people understand what the frequently misunderstood term “regression to the mean” actually … means:

Kwesi Adofo-Mensah, General Manager of the Minnesota Vikings. Adofo-Mensah was hired in 2022 to replace Rick Spielman.

Photo from the team website – https://www.vikings.com/team/front-office-roster/kwesi-adofo-mensah

The sports analytics movement has proven time and again to help teams win games, across sports and leagues, and so unsurprisingly essentially every team in every major sport employs an analytics department. I in fact find it very annoying that there are still statheads that act like they’re David and not Goliath for this reason. I also think that the impact of analytics on baseball has been a disaster from an entertainment standpoint. There’s a whole lot one could say about the general topic. (I frequently think about the fact that Moneyball helped advance the course of analytics, and analytics is fundamentally correct in its claims, and yet the fundamental narrative of the book was wrong.*) But while the predictive claims of analytics continue to evolve, they’ve been wildly successful.

I want to address one particular bugaboo I have with the way analytical concepts are discussed. It was inevitable that popularizing these concepts was going to lead to some distortion. One topic that I see misused all the time is regression/reversion to the mean, or the tendency of outlier performances to be followed up by performances that are closer to the average (mean) performance for that player or league. (I may use reversion and regression interchangeably here, mostly because I’m too forgetful to keep one in my head at a time.) A guy plays pro baseball for five years, he hits around 10 or 12 homeruns a year, then he has a year where he hits 30, then he goes back to hitting in the low 10s again in following seasons – that’s an example of regression to the mean. After deviation from trends we tend (tend) to see returns to trend. Similarly, if the NFL has a league average of about 4.3 yards per carry for a decade, and then the next year the league average is 4.8 without a rule change or other obvious candidate for differences in underlying conditions, that’s a good candidate for regression to the mean the next year, trending back towards that lower average. It certainly doesn’t have to happen, but it’s likely to happen for reasons we’ll talk about.

Intuitively, the actual tendency isn’t hard to understand. But I find that people talk about it in a way that suggests a misunderstanding of why regression to the mean happens, and I want to work through that here.

So. We have a system, like “major league baseball” or “K-12 public education in Baltimore” or “the world”. Within those systems we have quantitative phenomena (like on-base percentage, test scores, or the price of oil) that are explainable by multiple variables, AKA the conditions in which the observed phenomena occur. Over time, we observe trends in those phenomena, which can be in the system as a whole (leaguewide batting average), in subgroups (team batting average), or individuals (a player’s batting average). Those trends are the result of underlying variables/conditions, which include internal factors like an athlete’s level of ability, as well as elements of chance and unaccounted-for variability. (We could go into a big thing about what “chance” really refers to in a complex system, but … let’s not.) The more time goes on, and the more data is collected, the more confidently we can say that a trend is an accurate representation of some underlying reality, again like an athlete’s level of ability. When we say a baseball player is a good hitter, it’s because we’ve observed over time that he has produced good statistics in hitting, and we feel confident that this consistency is the product of his skill and attributes rather than exogenous factors.

However, we know that good hitters have bad games, just as bad hitters have good games. We know that good hitters have slumps where they have bad three or five or ten etc game stretches. We even acknowledge that someone can be a good hitter and have a bad season, or at least a season that’s below their usual standards. However, if a hitter has two or three bad seasons, we’re likely to stop seeing poor performance as an outlier and change our overall perception of the player. The outlier becomes the trend. There is no certain or objective place where that transition happens.

Here’s the really essential point I want to make: outliers tend to revert to the mean because the initial outlier performance was statistically unlikely; a repeat of that outlier performance is statistically unlikely for the same reasons, but not because of the previous outlier. For ease of understanding let’s pretend underlying conditions stay exactly the same, which of course will never happen in a real-world scenario. If that’s true, then the chance of having an equally unlikely outcome is exactly as likely as the first time; repetition of outliers is not made any less likely by the fact that the initial outlier happened. That is, there’s no inherent reason why a repetition of the outlier becomes more unlikely, given consistent underlying conditions. I think it’s really important to avoid the Gambler’s Fallacy here, thinking that a roulette wheel is somehow more likely to come up red because it’s come up black a hundred times in a row. Statistically unlikely outcomes in the past don’t make statistically unlikely outcomes any less likely in the future. The universe doesn’t “remember” that there’s been an outlier before. Reversion to the mean is not a force in the universe. It’s not a matter of results being bent back into the previous trend by the gods. Rather, if underlying conditions are similar (if a player is about as good as he was the previous year and the role of variability and chance remains the same), and he had an unlikely level of success/failure the prior year, he’s unlikely to repeat that performance because reaching that level of performance was unlikely in the first place.

* – the A’s not only were not a uniquely bad franchise, they had won the most games of any team in major league baseball in the ten years prior to the Moneyball season

– major league baseball had entered an era of unusual parity at that time, belying Michael Lewis’s implication that it was a game of haves and have-nots

– readers come away from the book convinced that the A’s won so many games because of Scott Hatteberg and Chad Bradford, the players that epitomize the Moneyball ethos, but the numbers tell us they were so successful because of a remarkably effective rotation in Tim Hudson, Barry Zito, and Mark Mulder, and the offensive skill of shortstop Miguel Tejada – all of whom were very highly regarded players according to the old-school scouting approach that the book has such disdain for.

– Art Howe was not an obstructionist asshole.

July 18, 2022

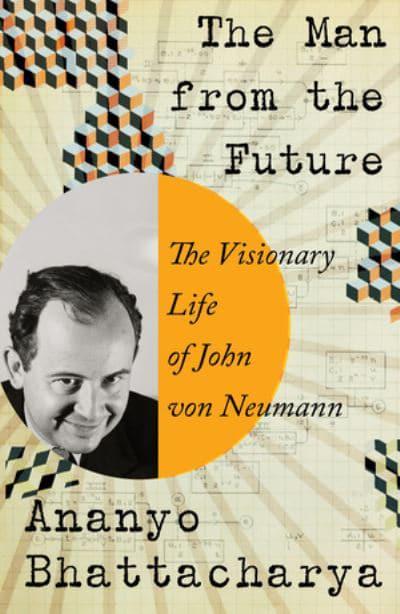

John von Neumann, The Man From The Future

One of the readers of Scott Alexander’s Astral Codex Ten has contributed a review of The Man From The Future: The Visionary Life of John von Neumann by Ananyo Bhattacharya. This is one of perhaps a dozen or so anonymous reviews that Scott publishes every year with the readers voting for the best review and the names of the contributors withheld until after the voting is finished:

John von Neumann invented the digital computer. The fields of game theory and cellular automata. Important pieces of modern economics, set theory, and particle physics. A substantial part of the technology behind the atom and hydrogen bombs. Several whole fields of mathematics I hadn’t previously heard of, like “operator algebras”, “continuous geometry”, and “ergodic theory”.

The Man From The Future, by Ananyo Bhattacharya, touches on all these things. But you don’t read a von Neumann biography to learn more about the invention of ergodic theory. You read it to gawk at an extreme human specimen, maybe the smartest man who ever lived.

By age 6, he could multiply eight-digit numbers in his head. At the same age, he spoke conversational ancient Greek; later, he would add Latin, French, German, English, and Yiddish (sometimes joked about also speaking Spanish, but he would just put “el” before English words and add -o to the end). Rumor had it he memorized everything he ever read. A fellow mathematician once tried to test this by asking him to recite Tale Of Two Cities, and reported that “he immediately began to recite the first chapter and continued until asked to stop after about ten or fifteen minutes”.

A group of scientists encountered a problem that the computers of the day couldn’t handle, and asked von Neumann for advice on designing a new generation of computers that was up to the task. But:

When the presentation was completed, he scribbled on a pad, stared so blankly that a RAND scientist later said he looked as if “his mind had slipped his face out of gear”, then said “Gentlemen, you do not need the computer. I have the answer.” While the scientists sat in stunned silence, Von Neumann reeled off the various steps which would provide the solution to the problem.

Do these sound a little too much like urban legends? The Tale Of Two Cities story comes straight from the mathematician involved — von Neumann’s friend Herman Goldstine, writing about his experience in The Computer From Pascal to von Neumann. The computer anecdote is of less certain provenance, quoted without attribution in a 1957 obituary in Life. But this is part of the fun of reading von Neumann biographies: figuring out what one can or can’t believe about a figure of such mythic proportions.

This is not really what Bhattacharya is here for. He does not entirely resist gawking. But he is at least as interested in giving us a tour of early 20th century mathematics, framed by the life of its most brilliant practitioner. The book devotes more pages to set theory than to von Neumann’s childhood, and spends more time on von Neumann’s formalization of quantum mechanics than on his first marriage (to be fair, so did von Neumann — hence the divorce).

Still, for those of us who never made their high school math tutors cry with joy at ever having met them (another von Neumann story, this one well-attested), the man himself is more of a draw than his ergodic theory. And there’s enough in The Man From The Future — and in some of the few hundred references it cites — to start to get a coherent picture.

December 30, 2021

QotD: Richard Feynman discovers (to his shock) that females can understand analytic geometry

I would like to report other evidence that mathematics is only patterns. When I was at Cornell, I was rather fascinated by the student body, which seems to me was a dilute mixture of some sensible people in a big mass of dumb people studying home economics, etc. including lots of girls. I used to sit in the cafeteria with the students and eat and try to overhear their conversations and see if there was one intelligent word coming out. You can imagine my surprise when I discovered a tremendous thing, it seemed to me.

I listened to a conversation between two girls, and one was explaining that if you want to make a straight line, you see, you go over a certain number to the right for each row you go up – that is, if you go over each time the same amount when you go up a row, you make a straight line – a deep principle of analytic geometry! It went on. I was rather amazed. I didn’t realize the female mind was capable of understanding analytic geometry.

She went on and said, “Suppose you have another line coming in from the other side, and you want to figure out where they are going to intersect. Suppose on one line you go over two to the right for every one you go up, and the other line goes over three to the right for every one that it goes up, and they start twenty steps apart,” etc. – I was flabbergasted. She figured out where the intersection was. It turned out that one girl was explaining to the other how to knit argyle socks. I, therefore, did learn a lesson: The female mind is capable of understanding analytic geometry. Those people who have for years been insisting (in the face of all obvious evidence to the contrary) that the male and female are equally capable of rational thought may have something. The difficulty may just be that we have never yet discovered a way to communicate with the female mind. If it is done in the right way, you may be able to get something out of it.

Richard Feynman, “What is Science?”, Richard Feynman [presented at the fifteenth annual meeting of the National Science Teachers Association, 1966 in New York City, and reprinted from The Physics Teacher Vol. 7, issue 6, 1969].

November 20, 2021

DicKtionary – M is for Mathematics – Newton and Hooke

TimeGhost History

Published 19 Nov 2021Today we turn away from killers and sociopathic rulers and look at two men from the world of science. Isaac Newton and Robert Hooke were certainly very intelligent and creative, but were they dicks as well?

(more…)

June 28, 2021

Pounds, shillings, and pence: a history of English coinage

Lindybeige

Published 18 Dec 2020I talk for a bit the history of English coinage, and the problems of maintaining a good currency. Once or twice I might stray off topic, but I end with an explanation of why the system worked so well.

Picture credits:

40 librae weight

Martinvl, CC BY-SA 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/…, via Wikimedia CommonsSceat K series, and others

By Classical Numismatic Group, Inc. http://www.cngcoins.com, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index…William I penny, and Charles II crown

The Portable Antiquities Scheme/ The Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-SA 2.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/…, via Wikimedia CommonsBust of Charlemagne

By Beckstet – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index…Edward VI crown

By CNG – http://www.cngcoins.com/Coin.aspx?Coi…, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index…Charles II guinea

Gregory Edmund, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/…, via Wikimedia CommonsSupport me on Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/Lindybeige

Buy the music – the music played at the end of my videos is now available here: https://lindybeige.bandcamp.com/track…

Buy tat (merch):

https://outloudmerch.com/collections/…Lindybeige: a channel of archaeology, ancient and medieval warfare, rants, swing dance, travelogues, evolution, and whatever else occurs to me to make.

▼ Follow me…

Twitter: https://twitter.com/Lindybeige I may have some drivel to contribute to the Twittersphere, plus you get notice of uploads.

My website:

http://www.LloydianAspects.co.uk

April 8, 2021

QotD: Thomas Hobbes and his “state of nature”

One reason I had such a hard time teaching this stuff to undergraduates back in my ivory tower days was that, ironically, we can imagine a much more “realistic” State of Nature than Hobbes could. We even had a TV show about it: Lost (in which, I’m told, one of the characters was actually named “John Locke”). A large group of strangers, unrelated by blood or affinity, would never be shipwrecked on a deserted island in Hobbes’s day, but we Postmoderns have no problem imagining a large international flight going down. Assume everyone survives the crash, and there’s your State of Nature – a much better one than Hobbes’s.

Under those very specific conditions, something like what Hobbes says might come to pass. In reality, of course, we seem to be much likelier to pull together in a disaster than to immediately go full retard, but let’s envision the most apocalyptic scenario, in which every guy who can bench press his body weight (assuming such still exist on international flights) immediately tries to lord it over everyone else on the island. There, and only there, the stuff Hobbes says about equality is true – the strong guy can beat up the weak guy, and enslave him, but the strong guy has to sleep sometime …

… so pretty soon there are no more strong guys, only various flavors of weak, clever guys, and now they have to band together, because you need three or four of them to accomplish the physical labor that one strong guy could’ve before they murdered him in his bed. And so on, you get the point, eventually everyone grudgingly lays down his arms and starts working together for mutual survival.

At this point, I need to point out something fundamental about Thomas Hobbes, that y’all probably don’t know. Hobbes always considered himself first and foremost a mathematician. But he wasn’t a very good mathematician. He’d thought he’d discovered a way to “square the circle,” for instance, and that’s not a metaphor – that was really a thing back then, and Hobbes’s attempt got ripped to shreds by real mathematicians, who thought they were thereby discrediting his metaphysics and, by implication, his political philosophy …

… fun stuff, but irrelevant, the point is, Hobbes was a bad mathematician. So bad, in fact, that even I, a former History professor who needs to pull off a sock every time I have to count past ten, can see the glaring flaw in his “geometrical” political theory: IF it’s based on “the State of Nature,” and we legitimize the Leviathan because that’s what gets us out of the State of Nature, then once we are free of the State of Nature, what’s the point of the Leviathan?

Hobbes didn’t see it that way, of course. He thought that we really did revert to “the war of all against all” the minute the social contract was broken, and in his context – the English Civil Wars, recall – that’s not unreasonable. But what about all the periods of “normal” government? You know, those periods of peace we created the Leviathan specifically to secure? If we get those – and there’s no point to the exercise otherwise – then we seem to have created an all-powerful government that, while it CAN do everything, really shouldn’t do anything.

Severian, “Hobbes (II)”, Founding Questions, 2020-12-11.

March 20, 2021

Iron cannon, improved celestial navigation techniques, and “race-built” galleons

In the latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes considers some of the technological innovations which helped English sailors to overcome powerful adversaries of the Spanish and Portuguese navies in the late 1500s and early 1600s:

Stern view of a model of the Revenge as an example of a race-built galleon, 1577.

Image from modellmarine.de

Apart from the adoption and refinement of celestial navigation techniques, however, English seafaring capabilities also benefited from some more obvious, physical changes. In 1588, for example, on the eve of the Spanish Armada, a senior Spanish officer believed that the English had “many more long-range guns”. By the 1540s, medieval ironmaking techniques involving the blast furnace had gradually spread from Germany, to Normandy, and thence to the Weald of Sussex and Kent. Whereas in the first half of the sixteenth century England had typically imported three quarters of its iron from Spain, by 1590 it had not only quintupled its consumption of iron but was also almost entirely self-sufficient. And by allowing England to exploit its plentiful domestic deposits of iron, the blast furnace resulted in it producing many more cheap cannon.

Iron guns were in many ways worse for ships than those of bronze. They were heavier, prone to corrosion, and more likely to explode without warning. Bronze guns, by contrast, would first bulge and then split, but in any case tended to last. When the British captured Gorée off the coast of Senegal in 1758, they found a working English-made bronze cannon that dated from 1582. Yet iron was only 10-20% the price of bronze. Although the Royal Navy for decades continued to prefer bronze, cheap, medium-sized cannon of iron proliferated, becoming affordable to merchants, pirates, and privateers — a situation that was unique to England.

English ships were thus especially well-armed, allowing them to access new markets even when they sailed into hostile waters. They were soon some of the only merchants able to hold their own against the latest Mediterranean apex predator, whether it be the Spanish navy, Algeria-based corsairs, or Ottoman galleys. And they were able to insert themselves, sometimes violently, into the inter-oceanic trades — all despite the armed resistance of the Spanish and Portuguese, who had long monopolised those routes. In the 1560s, John Hawkins tried a few times to muscle in on the transatlantic Portuguese and Spanish trade in slaves. With backing from the monarch and her ministers, he captured Portuguese slave ships, raided and traded along the African coastline himself, and then sold slaves in the Spanish colonies of the Americas, sometimes having to attack those colonies before the local governor would allow them to trade. (The attempt was ultimately unsuccessful, as Hawkins’s privateering fleet was all but destroyed in 1568 and the English were not involved in the slave trade again for almost a century.)

The English hold over the hostile markets was only threatened during times of peace on the continent, when their ships’ defensiveness no longer gave them a special advantage. The Dutch usurped English dominance of the trade with Iberia and the Mediterranean, for example, during the Dutch Republic’s truce with Spain 1609-21. Their more efficient ships, especially for bulk commodities — the fluyt invented at Hoorn in the late 1580s — were cheaper to build, required fewer sailors, and were easier to handle. But these advantages only made them competitive when the risk of attack was low, as they were hardly armed. When wars resumed, the English had a chance to regain their position.

Finally, the English acquired a few further advantages when it came to ship design. Thanks to the shipwright Matthew Baker, who had been on the trial voyage Cabot dispatched to the Mediterranean, England experienced a revolution in using mathematics to design ships. Baker’s methods, seemingly developed in the 1560s, allowed him to more cheaply experiment with new forms, and by the 1570s these began to bear fruit. The old ocean-going carracks and galleons, with their high forecastles and aftercastles, became substantially sleeker. Taking inspiration from nature, Baker designed a streamlined, elongated hull modelled below the waterline upon a cod’s head with a mackerel tail. Above the waterline, too, he lowered the forecastle and set it further back, as well as flattening the aftercastle.

Starting in 1570 with his prototype the Foresight, and more fully developed in 1575-77 with the Revenge, these razed or “race-built” galleons gave the English some significant advantages. Drake even chose the Revenge as his flagship to battle the Spanish Armada in 1588, and to lead an ill-fated reprisal invasion of Portugal the following year. The higher castles of carracks and old-style galleons were suited to clearing an enemy’s decks with arrows and gunfire, as well as to defend against boarders. They were designed for combat at close quarters, in which height was an advantage. They were floating fortresses, their imposing height known to inspire terror. The race-built galleons, by contrast, by making the ship less top-heavy, could have longer and lower gundecks, with more of the ship’s displacement devoted to ordnance — especially useful when taking advantage of the cheaper but heavier cannon made of iron. Rather than killing an enemy ship’s sailors and soldiers, the race-built galleons were optimised for blasting through its hull. What they lost in “majesty and terror”, they made up for with overwhelming firepower. They aimed to sink.

March 5, 2021

Schools told they need to “identify and challenge the ways that math is used to uphold capitalist, imperialist, and racist views”

No wonder I had trouble with math back in grade school: Math is a racist tool of White Supremacists!

“Math Class” by attercop311 is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Mandatory teaching standards that focus on critical theory and identity politics to the detriment of liberalism and individualism are already working their way through state legislatures.

Now, math education itself has been deemed “racist.” A group of educators just released a document calling for a transformation of math education that focuses on “dismantling white supremacy in math classrooms by visibilizing the toxic characteristics of white supremacy culture with respect to math.”

Among the educators’ recommendations, which officials in some states are promoting, are calls to “identify and challenge the ways that math is used to uphold capitalist, imperialist, and racist views,” “provide learning opportunities that use math as resistance,” and “encourage them to disrupt the disproportionate push-out of people of color in [STEM] fields.”

Beyond activism, these recommendations also argue that traditional approaches to math education promote racism and white supremacy, such as requiring students to show their work or prioritizing correct answers to math problems. The document claims that current math teaching is problematic because it focuses on “reinforcing objectivity and the idea that there is only one right way” while it “also reinforces paternalism.”

October 30, 2020

Halloween Special: H. P. Lovecraft

Overly Sarcastic Productions

Published 31 Oct 2018HAPPY HALLOWEEN IT’S TIME TO GET SPOOKY WITH HISTORY’S MOST PROBLEMATIC HORROR WRITER LET’S GOOOOO

While there’s something to be said for separating the art from the artist, I think there’s a lot of merit in CONTEXTUALIZING the art WITH the artist. Did Lovecraft write some pretty incredible horror? Sure! Was he also a raging xenophobe? Absolutely! Are his perspectives on life connected with the stories he felt compelled to tell? Duh! If you look at Lovecraft’s writing through the lens of his life, clear patterns emerge that allow us to pin down what exactly he built his horror cosmology out of. It’s an invaluable analytical tool that allows us to take apart his writings by getting inside his head. So before you yell at me for Not Separating The Artist From The Art, know that it was completely intentional and I’m not sorry.

3:20 – THE CALL OF CTHULHU

8:40 – COOL AIR

10:36 – THE COLOR OUT OF SPACE

14:38 – THE DUNWICH HORROR

19:32 – THE SHADOW OVER INNSMOUTHPATREON: www.patreon.com/user?u=4664797

MERCH LINKS:

Shirts – https://overlysarcasticproducts.threa…

All the other stuff – http://www.cafepress.com/OverlySarcas…

From the comments:

Overly Sarcastic Productions

1 year ago

Hey gang! Can’t help but notice the comment section is a little bit on fire. That’s all good with me, but one recurring complaint I’ve noticed has started to get under my skin – namely that my explanation of non-euclidean geometry was insufficient, or even – dare I say – inaccurate. Now this is a fair complaint, because after a lifetime of experience finding that people’s eyes glaze over when I talk math at them, I concluded that interrupting a half-hour horror video with a long-winded explanation of a mathematical concept wouldn’t go over too well. I put it in layman’s terms and used a simple example to illustrate the point. However, since some of the more mathematically-inclined of you took offense, I now present in full a short (but comprehensive) explanation of what exactly non-euclidean geometry is.First, we axiomatically establish euclidean geometry. Euclidean geometry has five axioms:

1. We can draw a straight line between any two points.

2. We can infinitely extend a finite straight line.

3. We can draw a circle with any center and radius.

4. All right angles are equal to one another.

5. If two lines intersect with a third line, and the sum of the inner angles of those intersections is less than 180º, then those two lines must intersect if extended far enough.Axiom #5 is known as the PARALLEL POSTULATE. It has many equivalent statements, including the Triangle Postulate (“the sum of the angles in every triangle is 180º”) and Playfair’s Axiom (“given a line and a point not on that line, there exists ONE line parallel to the given line that intersects the given point”).

Euclidean geometry is, broadly, how geometry works on a flat plane.

However, there are geometries where the parallel postulate DOES NOT hold. These geometries are called “non-euclidean geometries”. There are, in fact, an infinite number of these geometries, and because the only defining characteristic is “the parallel postulate does not hold”, they can be all kinds of crazy shapes. (As you can see, my explanation of “this is just how geometry works on a curved surface” is quite reductive, but at the same time serves to get the general impression across without going into too much detail.)

An example of a non-euclidean geometry is “Elliptic geometry”, geometry on n-dimensional ellipses, which includes “Spherical geometry” as a subset. Spherical geometry is, predictably enough, how geometry works on the two-dimensional surface of a three-dimensional sphere.

In spherical geometry, “points” are defined the same as in euclidean geometry, but “line” is redefined to be “the shortest distance between two points over the surface of the sphere”, since there is no such thing as a “straight line” on a curved surface. All “lines” in spherical geometry are segments of “great circles” (which is defined as the set of points that exist at the intersection between the sphere and a plane passing through the center of that sphere).

The axiom that separates spherical geometry from euclidean geometry and replaces the parallel postulate is “5. There are NO parallel lines”. In spherical geometry, every line is a segment of a great circle, and any two great circles intersect at exactly two points. If two lines intersect when extended, they cannot be parallel, and thus there are no parallel lines in spherical geometry.

Since the Parallel Postulate is equivalent to Playfair’s Axiom, the fact that no parallel lines exist in spherical geometry negates Playfair’s Axiom, which thus negates the Parallel Postulate and defines spherical geometry as a non-euclidean geometry. Also, since the Triangle Postulate is another equivalent property to the Parallel Postulate, it is thus negated in spherical geometry. Hence, my use in-video of an example of a triangle drawn on the surface of a sphere whose inner angles sum greater than 180º.

Hope that cleared things up (and helped explain why I didn’t want to say “see, non-euclidean geometry is just a geometry where Euclid’s Parallel Postulate doesn’t hold – hold on, let me get the chalkboard to explain what THAT is-” in the video)

Peace!

-R