The Gillian Duffy affair, the start of this People’s Decade, was fascinating on many levels. Fundamentally, it revealed the schism in values and language that separated the elites from ordinary people. To the professional middle classes who by that point — after 13 years of New Labour government — had conquered the Labour Party, people like Mrs Duffy were virtually an alien species, and places like Rochdale were almost another planet. Indeed, one small but striking thing that happened in the Duffy / Brown fallout was a correction published in the Guardian. One of that newspaper’s initial reports on the Duffy affair had said that Rochdale was “a few hundred miles” from London. Readers wrote in to point out that it is only 170 miles from London. To the chattering classes, it was clear that Rochdale was as faraway and as foreign as Italy or Germany. More so, in fact.

The linguistic chasm between Duffy and Brown spoke volumes about Labour’s turn away from its traditional working-class base. Yes, there was the word “bigot”, but, strikingly, that wasn’t the word that most offended Mrs Duffy. No, she was most horrified by Brown’s description of her as “that woman”. “The thing that upset me was the way he said ‘that woman'”, she said. “I come from the north and when you say ‘that woman’, it’s really not very nice. Why couldn’t he have just said ‘that lady’?”

One reason Brown probably didn’t say “lady” is because in the starched, aloof, technocratic world New Labour inhabited, and helped to create, the word “lady” had all but been banned as archaic and offensive in the early 2000s. Since the millennium, various public-sector bodies had made moves to prevent people from saying lady to refer to a woman. One college advised against using the word lady, as it is “no longer appropriate in the new century”. An NHS Trust instructed its workers that “lady” is “not universally accepted” and should thus be avoided. In saying “that woman”, Brown was unquestionably being dismissive — “that piece of trash” is what he really meant — but he was also speaking in the clipped, watchful, PC tones of an elite that might have only been 170 miles from Rochdale (take note, Guardian) but which was in another world entirely in terms of values, outlook, culture and language.

“I’m not ‘that woman'”, said Duffy, and in many ways this became the rebellious cry of the People’s Decade. She was pushing back against the elite’s denigration of her. Against its denigration of her identity (as a lady), of her right to express herself publicly (“it’s just ridiculous”, as Brown said of that very public encounter), and most importantly of her concerns, in particular on the issue of immigration and its relationship to the welfare state.

The Brown-Duffy stand-off at the start of the People’s Decade exposed the colossal clash of values that existed between the new political oligarchy represented by Brown, Blair and other New Labour / New Conservative machine politicians and the working-class heartlands of the country. To Duffy and millions of other people, the relationship between welfare and nationhood was of critical importance. That is fundamentally what she collared Brown about. There are “too many people now who are not vulnerable but they can claim [welfare]”, she said, before asking about immigration. Her suggestion, her focus on the issue of health, education and welfare and the question of who has access to these things and why, was a statement about citizenship, and about the role of welfare as a benefit of citizenship. But to Brown, as to virtually the entire political class, it was just bigotry. Concern about community, nationhood and the impact of immigration is just xenophobic Little Englandism in the minds of the new elites. This was the key achievement of 13 years of New Labour’s censorious, technocratic and highly middle-class rule — the reduction of fealty to the nation to a species of bigotry.

Brendan O’Neill, “The People’s Decade”, Spiked, 2019-12-27.

March 21, 2025

QotD: Gordon Brown and the “Gillian Duffy affair”

February 1, 2025

China produced DeepSeek, Britain is mired in deep suck

In the Sean Gabb Newsletter, Sebastian Wang discusses the contrast between China’s recent release of the DeepSeek AI platform that appears to be eating the collective lunches of the existing LLM products by US firms and the devotion of the British Labour government to plunge ever deeper into their Net Zero dystopian vision:

For those few readers who may be unaware, DeepSeek is an advanced open-source artificial intelligence platform developed in China. Released in late 2024, it has set a new standard in AI, outperforming American counterparts in adaptability and capability. It excels in natural language processing, machine learning, and data analysis, and — critically — it is open source. Unlike the proprietary models that dominate the American tech landscape, DeepSeek allows anyone to adapt, improve, and use it as he sees fit. It’s not just a technological triumph for China; it’s a serious challenge to American domination of information technology and an opportunity for those who want to break free from the stranglehold of Silicon Valley.

As a Chinese person, I take pride in this achievement. It’s a testament to what my people can achieve with focus and ambition. But my concern is less about taking pride in what China has done and more about lamenting how little Britain has contributed to this revolution. Britain, the birthplace of the Industrial Revolution, seems to have no place in this new world of AI-driven progress. The question is why?

The answer is simple: The people who rule Britain have chosen decline. Crushing taxes on income and capital gains, and inheritance taxes, punish those who want to create wealth. Endless regulations stifle ambition, making it easier to conform than to innovate. Worst of all, there are the net zero policies, which have made energy costs the highest in the world, making electricity unaffordable and unreliable. Industries that depend on energy have been priced out of existence, and the dreamers and doers who might have built the next DeepSeek are being ground down by a system designed to reward mediocrity.

Net zero is not a noble goal born of misconception; it’s a disaster by design. It’s a wealth transfer scheme that takes from ordinary working people and hands billions to a small clique of green profiteers. The winners are the wind farm builders, the financiers running opaque carbon trading schemes, and the activists cashing in on government handouts. The losers are everyone else — families struggling to pay energy bills, businesses forced to close, and an entire country left unable to compete.

Compare this to China. DeepSeek wasn’t luck — it was the product of a system that rewards innovation. Electricity in China is cheap and reliable. Regulations focus on enabling progress, not blocking it. Ambition is celebrated, not treated as a threat. The ruling class there, for all its many and terrible faults, understands the value of creating wealth and technological self-reliance. Britain’s ruling class, by contrast, has abandoned the idea of building anything. They’d rather sit in the City of London, counting money made elsewhere, than see industry and innovation flourish in the country at large. They have chosen decline — not for them, but for us.

December 13, 2024

Kemi Badenoch … a Thatcher for the 2020s?

In The Free Press, Oliver Wiseman wonders if new British Conservative Party leader Kemi Badenoch will do for her party what Margaret Thatcher did after she was elected leader in 1975:

“I like fixing things that are broken,” says Kemi Badenoch in her interview with Bari on the latest episode of Honestly. Badenoch, 44, was elected as the new leader of the UK’s Conservatives last month. And luckily for her, there are a lot of things that are broken.

One of them is her party.

In July, after fourteen years in office, the Tories were unceremoniously booted from power. They lost more than 250 of their Members of Parliament in the biggest electoral defeat in the party’s history. On the long road back to power, Badenoch must contend not only with a Labour government with a huge majority in Parliament, but also Nigel Farage — the Brexit-backing populist is on a mission to supplant the Conservative Party as the main alternative to Labour.

If Badenoch somehow manages to fix her party and return to power, she must then figure out a way to fix Britain — a country where wages have stagnated for a generation, public debt has ballooned, and there’s widespread anger at high rates of immigration. As another Brit, Free Press columnist Niall Ferguson, put it recently in these pages: “Lately it seems that mine is a country with a death wish.” (Read his full account of what ails the UK here.)

In other words, Badenoch has a daunting in tray. And yet many — including Niall — are bullish on Badenoch, who he believes could be a “black Thatcher”.

As a woman in charge of the Conservative Party, Badenoch was bound to be compared to the Iron Lady. But in this case there are undeniable parallels. Much like Thatcher, Badenoch mixes steely determination with charm and charisma. She also, like Thatcher, knows what she believes. Her diagnosis of her party’s problems is straightforward: It has strayed too far from the values that have historically made it — and Britain — so successful.

And while Thatcher and Badenoch’s backgrounds are very different — one grew up in provincial England, the other spent most of her childhood in Nigeria — they are both self-made women with an appetite for hard work. Badenoch’s own story, and her family’s, is central to her politics. “I know what it is like to be wealthy and also to be poor,” she says today on Honestly.

There’s one other Badenoch–Thatcher parallel: the circumstances in which they took over their party’s leadership. Thatcher became Tory leader in 1975 — then, like today, a malaise had descended over the country, one that would lift during her time in office. These comparisons may be unavoidable, but does Badenoch welcome them? Bari asked her that in their conversation. “She is a heroine of mine. So it’s very flattering,” said Badenoch. “But it’s also quite heavy and she’s a different person. I admire her. But I want people to recognize that I’m not a pastiche of this person, that I am my own person.”

November 7, 2024

Kemi Badenoch portrayed by the left as “the most prominent member of white supremacy’s black collaborator class”

The left likes to think themselves the faction of racial equality, yet they often reveal themselves to be anything but when someone steps out of line (from their point of view) and chooses a different political worldview:

For centuries, Britain was ruled by an aristocracy. In recent decades, however, this concept has become rather passé, and we have been doing away with it — most recently with the vote to abolish hereditary peers in the House of Lords.

Yet, as the old guard fades, a new elite has taken its place. Inherited traits — particularly skin colour and sex — now grant special dispensations. Utterances that would be unthinkable for most are allowed, and positions incommensurate to talent are dispensed.

This is because the new aristocracy is flush, often through little toil of its own, with moral authority — a valuable currency wielded by what we might call the Patricians of Victimhood.

Their power rests on the idea that Britain is a fundamentally racist country, brimming with other nasty “isms” that can be contained only by them. To deny this is heresy — but to disprove it is a crime for which no punishment is too great.

This was evident when Kemi Badenoch, a black woman, was elected Saturday to lead the Conservative Party. This historic first for Britain might have been expected to please those preoccupied with combating racism, perhaps even chalked up as a win.

Instead, Badenoch was lambasted by politicians who have built careers campaigning about racism. Dawn Butler, a Labour MP, shared a post accusing Badenoch of representing “white supremacy in blackface” — an insult so improbable that it conjures only an image of a face-painted Justin Trudeau.

The post, now removed from Butler’s X account, read: “Today the most prominent member of white supremacy’s black collaborator class (in Britain) is likely to be made leader of the Conservative Party. Here are some handy tips for surviving the immediate surge of Badenochism (i.e. white supremacy in blackface).”

Another Labour MP, Zara Sultana, said Badenoch was “one of the most nasty & divisive figures in British politics”, for, among other things, “downplaying racism”.

Badenoch is opposed to identity politics. She believes in meritocracy and that Britain — as she told her children recently — “is the best country in the world to be black”. Badenoch’s optimism is well founded: a 2023 World Values Survey found that Britain is indeed one of the least racist countries in the world.

November 3, 2024

Kemi Badenoch replaces Rishi Sunak as UK Conservative leader

In the National Post, Michael Murphy discusses the new British Tory leader and why she could be a viable challenger to Two-tier Keir’s Labour government:

… in July, the Tories were ousted by Labour after 14 years in power, limping on with only 121 seats in the 650 seat House of Commons. But the honeymoon period for Sir Keir Starmer’s Labour government ended almost immediately, as its popularity plummeted faster than that of any administration in recent memory. This has made the Tories interesting once again at precisely the moment when they’ve chosen a new leader: Kemi Badenoch.

The Nigerian-raised mother of three, elected today to lead the Conservative party, threatens to be kryptonite for a Labour party wedded to identity politics. A black, female immigrant at the dispatch box is apt to leave Labour frontbenchers — particularly Sir Keir, a one-time BLM kneeler — somewhat stumped. To make matters worse, Badenoch is a persuasive speaker, commanding a charisma and eloquence that Sir Keir — a dull, po-faced lawyer — does not possess.

These qualities have given Badenoch cross-party appeal within the Tories, rallying endorsements from both the left and right. By endorsing her, however, the party has effectively signed a blank cheque, as Badenoch, unlike her opponents, has made few specific pledges. She has chosen instead to reflect on the election loss and the party’s ideological roots; she is prepared to play the long game, hoping this will allow the Tories to “earn back trust”.

On some issues, though, Badenoch is clear. “The government is doing far too much and it is not doing any of it well — and it is growing and growing,” she declared recently. “The state is too big; we need to make sure there is more personal responsibility.” These ideas are common fare among Conservatives, especially in bloated welfare states like Britain — but her zeal for them evokes, for many, memories of Margaret Thatcher. As the political commentator Simon Heffer wrote, “Mrs Badenoch is the politician who most reminds me of Mrs Thatcher since I last saw Mrs Thatcher”. He noted both women’s hard-mindedness, “deep principles”, and grasp of the “art of the possible”.

Badenoch’s Conservatism can be traced, as the writer Tom Mctague has argued elsewhere, to her beginnings in Africa. Having fled Nigeria during a 1996 military coup, she has a keen, outsider’s appreciation for Britain’s core ideals — not least the rule of law and policing by consent. She is therefore a champion of Britain, of both “the good” and “bad” of its former empire, at a time when it is fashionable to denigrate it, precisely because of her first hand experience that these norms are rare and fragile.

Like Thatcher, Badenoch studied a hard science (computing), marking them out in a Parliament filled with lawyers and humanities graduates. And the swift rise of both women, from modest beginnings through the ranks of the Conservative party, suggests that the “art of the possible” is indeed etched into their stars.

The Armchair General has a few suggestions for Badenoch’s agenda to turn the British economy around:

My one reservation [about Badenoch] was that, being a software engineer, instead of espousing liberty or slashing laws and regulations, Kemi might reach for more tinkering technocratic solutions — and your humble General is surely not alone in his opinion that we have had quite enough, thank you, of technocratic governments.

However, the more that I consider the severe problems that afflict this country, the more I believe that a process-driven leader, who can focus on the details, might make the biggest difference in the short to medium term.

The immigration issue

As we know, uncontrolled immigration has seized the public imagination greatly — and, indeed, Jenrick centred his campaign around leaving the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR). We should almost certainly do this anyway — simply because, like the Americans, we should refuse to sign any treaties that raises foreign courts above our own Parliament.

But leaving that aside, the stated problems with mass immigration can largely be divided into two halves:

- cultural differences — these are not insignificant, and it is claimed that they lead to an increase in crime (especially sexual crimes) and an undermining of our high-trust society;

- economic issues — the evidence shows that a massive net influx of low-skilled immigrants depresses wages at the lower end, puts a strain on public services (which cannot expand swiftly enough to accommodate the increase in demand), raises the demand for houses (of which there is a shortage) and thus pushes up prices, and, ultimately, only increases nominal GDP whilst per capita GDP has barely shifted in a decade and a half.

For the purposes of this post, I shall address only the latter issue; given where we are right now, the former is a much thornier problem — at least politically — and probably cannot be solved without radical (and some might say “authoritarian”) action.

The second problem is easier to solve because it is caused, essentially, by the single biggest drag on our economy — our planning system.

[…]

Planning: the Conservatives’ political agenda

The core of the new Conservative manifesto must be a growth agenda; it needs to set out the following core principles:

- if we carry on the current trajectory, the British government will be effectively bankrupt in the next 50 years — so something needs to change;

- therefore, in order to pay for all the goodies that we have promised ourselves (now and in the future), we need to massively accelerate economic growth;

- unless we can build the roads, railways, power stations, research labs, data centres, and homes that we need, then our economy will not grow at the required rate — and spending will need to be cut to the bone;

- given the above, the only way to grow is to reform planning laws;

- removing the barriers to building will lead to greater investment, lower energy prices (leading to even greater investment), greater social mobility, regeneration of all the regions (so-called “levelling up”), and vast increases in per capita GDP;

- where the state invests in infrastructure, then it will cost considerably less than it does currently — meaning that not only will those projects undertaken provide more value for money, but also that many more projects will be viable;

- this prosperity and increased mobility will remove even the perceived need for immigrants to perform low-wage jobs (including in our public services), and remove the economic pressures of those that we have already taken in;1

- if we do it right, then we will also be able to cut taxes without drastically cutting the size of the state.2

The argument needs to be as stark and inevitable as that.

What this means is that the Conservatives need not stand on a platform of slashing state spending — thus addressing the huge numbers of people in this country who, incredibly, still believe in the benevolent state.

Except for one caveat, there really is no downside to adopting Foundations [discussed here], in full, as the core of the next Conservative manifesto (although it should not be the full extent of said manifesto — there are many other areas that need to be addressed, which I shall write about later).

1. As I say, the cultural issues are for another time.

2. Obviously, as a classical liberal, I believe that the size of the state should be drastically cut — but this is not a popular argument in a country that has been raised and educated on socialist doctrine for decades.

October 2, 2024

Poilievre should learn from “Two Tier” Keir’s political stumbles

Sir Keir Starmer swept into office just four months ago, but if you tracked the unforced errors, gaffes, stumbles and bumbles it might as well have been four years instead. Most politicians winning nearly 2/3rds of the seats in Parliament can expect a lengthy “honeymoon” period, but “Two Tier” Keir is far from a typical politician … he’s terrible at his new job. In The Line, Andrew MacDougall charts some of the worst self-inflicted wounds Starmer’s government has suffered and indicates how Pierre Poilievre can avoid them:

Prime Ministers Starmer and Trudeau at the NATO summit in Washington.

Image from Justin Trudeau’s X account.

If Conservative leader Pierre Poilievre thinks he’s halfway home to a happy life in power, he should look across the pond to see the misery now engulfing Sir Keir Starmer and his new Labour government.

Where to start? Sadly for Starmer, there is a smorgasbord of bad political choice.

[…]

And while Starmer did his level best to stay vague during the election campaign about his planned solutions, as all good opposition leaders do in order to minimize incoming attacks, he was meant to have a plan to sort it all out once he got into the building. But there’s no plan. And that’s according to sources inside 10 Downing Street. That’s right: we’re just three months into a majority parliament and a government with a virtually unopposable mandate and the calls are already coming from inside the building saying it’s all gone to shit.

As I was saying, it’s all very late-stage Trudeau.

Fortunately for Canadians who are desperate for a diversion from Trudeau’s path, Pierre Poilievre is a better politician than Keir Starmer. A vastly better politician. And while that might sound like a pejorative in an era where no politician is trusted, the pile of public policy muck heaps facing Western governments won’t be cleared without someone who understands — deeply and intuitively — the politics of the current time.

Starmer understands none of the current dynamic. He defeated the U.K. Conservatives because the U.K. Conservatives defeated themselves. The country would have taken anyone to stop the Tory psychodrama, even a boring North London lawyer who wouldn’t know politics if it smacked him on his newly-tailored arse. People are angry that nothing appears to be working as it should. Not the hospitals. Not the borders. Not the economy. And not their culture. Everything feels different and/or worse to what they’ve come to expect and they blame the (waves arms frantically) “establishment” for their ills. There’s a reason Nigel Farage’s Reform party won its first seats and came second in nearly a hundred more.

People who are already feeling stretched don’t want to hear, as they’ve heard from Starmer, that their taxes are going up. They want to hear they’re going to go down. “Axe the tax”, anyone? They don’t want to hear that things suck; they want to hear how things will get better. They don’t want to be sung hymns about the benefits of immigration. They want to see someone spot the problem that’s gotten out of control and assure them that it’s not racist to do something about it. They want someone who looks and sounds like them, not another politician in a suit saying things politicians in suits always say. They want radical change, not minor dial adjusting on the dashboards of power. Anything else is more of the discredited same.

Canada’s late-stage Trudeau inheritance is daunting. It cannot be avoided. But it must first be acknowledged, not by simply pointing at the last guy and saying “It’s all his fault” (i.e. the classic politician move), but by mirroring the real distress being felt by the many who’ve lost out where and as the traditional power brokers have won. This is where the room to manoeuvre comes from. Something has gone wrong and it’s going to take something different to produce a different result.

August 31, 2024

Britain’s police double down on “non-crime hate incidents” as a tool of repression

Andrew Doyle admits he was over-optimistic by predicting that the British police forces’ use of “non-crime hate incidents” — after court judgments and Home Office instructions to stop using them — would not last for much longer. That was in 2022:

“Metropolitan Police London England” by William Mewes is marked with CC0 1.0 .

I have a tendency to be over-optimistic. In my 2022 book The New Puritans, I wrote about “non-crime hate incidents” and how they were still being recorded by police, in spite of the Court of Appeal’s ruling that they were “plainly an interference with freedom of expression” and direct instructions from the Home Office that the police must stop this illiberal and unethical practice. However, I concluded that ultimately “it seems unlikely that ‘non-crime hate incidents’ will last for much longer”.

Of course I was wrong, because I had not counted on just how authoritarian a new Labour government might be. It was bad enough that the Education Secretary Bridget Phillipson scotched the Higher Education (Freedom of Speech) Act just one day before parliament went into recess — presumably to avoid having to debate the matter — but now the Home Secretary Yvette Cooper has reversed the Conservatives’ pledge to limit the recording of “non-crime”. Labour is bringing back this absurd policy, and has convinced itself that this is somehow a progressive measure.

It should go without saying that the police have no business recording “non-crime”, particularly when such records are based on accusations alone (that is to say, the “perception” of the “victim” is what counts, rather than actual evidence of hatred). The Tory government should have eliminated the entire practice in its entirety, but instead decided that such “incidents” ought to stay on record if there was a “real risk of escalation causing significant harm or a criminal offence”. The science fiction writer Philip K. Dick had a phrase for this: “pre-crime”.

So let’s leave aside the woefully inadequate restrictions put in place by the Tories. Let’s also leave aside the obvious point that hatred, along with all other emotions, will never be eradicated through legislation and that the state is wasting its time trying to alter human nature. Let’s focus instead on why the Labour government is so determined to control the speech and thought of its citizens.

How does it help anyone for the name of the schoolboy who accidentally scuffed a copy of the Koran at a school in Wakefield to be on police records? His “non-crime” was duly recorded after the event, but why? Does the government really suppose that this child is one step away from torching a mosque? Even if he had deliberately scuffed the Koran, what has this to do with the police? I don’t much approve of defacing books, but vandalism of one’s own property is a matter for individual conscience.

Of course, Labour will say that the recent riots have proven the necessity for cracking down on the private thoughts of citizens. In truth, these acts of violence are being exploited to justify further authoritarian policies. We have seen how quick our politicians are to seize upon these moments to advance their own goals. The murder of Sir David Amess had precisely nothing to do with social media, and yet politicians immediately began to argue that his death was evidence of the need to curb free speech online. This was grotesque opportunism from a political class that does not trust the public.

August 30, 2024

Two-Tier Keir’s “mask off” moment(s)

Millennial Woes presents a disturbingly long summary of British Prime Minister Keir Starmer’s responses to popular non-violent protests:

The situation in Britain now is so perverse that, if you could convey it to people from a century ago, I think they, after getting over the disbelief and astonishment and accepting that this really was true, would assume it could not possibly have come about by chance. Whatever their complaints about the Britain of 1900, they wouldn’t have believed it capable — on its own — of the degeneration we have seen. They would insist that it must have been wickedly subverted, every failsafe removed, and entire systems of governance, culture and morality repurposed, made to achieve the opposite of their purported function.

I hardly need list the symptoms of this, but for the sake of posterity …

- The control nexus (of which the government is merely one node) ships massive numbers of unassimilable foreigners into the country against the repeatedly expressed wishes of the natives, and in clear violation of their best interests.

- Natives who complain about this are hounded, doxed, demonised, made unemployable, and often imprisoned.

- Their children are systematically indoctrinated by fiction media to accept their dispossession. They are encouraged to despise the “bigoted” attitudes of their parents and grandparents, and to loathe their nation’s history. The boys are encouraged to idolise non-native men. The girls are encouraged to race-mix with them.

- Teachers deliver the same indoctrination in the classroom — in every classroom. You won’t be allowed to become a teacher unless you voice enthusiasm for such things. Alternative views have been eradicated from the classroom and the lecture hall.

- Natives are systematically disadvantaged in numerous sectors of education and employment.

- Natives are demonised in fiction and news media while non-natives are made to look wonderful.

- The mass sexual abuse of native children by non-natives is systematically down-played by news media, who shift discussion to false “equivalents”.

- Natives’ history is systematically distorted in education and fiction media.

- The very existence of the natives, as a group, and their ownership of their homeland, are systematically denied by education, fiction media, news media, and phoney “science”.

- The police do whatever they are told to do, kneeling for the participants in one riot, hunting down the participants in a different riot.

- Judges pass obviously outrageous prison sentences upon certain people, for blatantly political reasons. These people are denied bail and pressured to plead guilty for fear of sentences even more outrageous. All of this is to send a message to other people: “don’t dare complain or the same will happen to you”.

- The media rushes to concoct fake narratives about events, to keep the public misinformed.

- A so-called “charity”, which is heavily linked to the government and the civil service, seeks to indoctrinate the young and ruin the lives of “troublemakers”, and actively aids the government in concocting fake narratives in order to control public thought and direct events.

- Fake news from such Establishment agents is forgiven, fake news from the Establishment’s enemies is answered with threats of prosecution.

- The media “memory hole” stories of appalling violence by non-natives, explain away such incidents with talk of mental illness, tell natives “don’t look back in anger”, and at all costs defend the suicidal ideologies that make such incidents possible.

- The prisons are emptied of rapists, child molesters and murderers so that troublesome natives can be assigned their cells. They are placed alongside non-natives who might well be violent to them, and journalists gloat about it.

- The slaughtering of three little girls by a non-native is dismissed by the Prime Minister, who says “it doesn’t matter” that the rioting was a response to this outrageous crime, which was enabled by the outrageous government policies that the natives have been complaining about for decades. Their shock, their trauma, their resentment, their dignity, their pain… “doesn’t matter”. This is in stark contrast with how he reacted to Black people rioting several years before.

- The natives’ freedom of speech is continually undermined, one government after another actively seeking to erode it further.

- Not one single organisation is fighting for the wellbeing, rights or interests of the natives.

- Any political party that would do anything about any of this is refused the right to stand in elections, debanked, demonised and, in most cases, destroyed.

Any one of these examples would, in itself, be cause for great alarm. The whole lot together indicate a society that is not just largely, not just fundamentally, but wholly opposed to the continued existence of its native population. To underline: British society is actively perpetrating the destruction of the native British people.

It has been said that the ruthless authoritarian response of the fledgling Starmer government to this summer’s (White) riots is a “mask off” moment for the Labour Party. Others have called it a “mask off” moment for the British Establishment, which transcends the particular party in office. Indeed, things that didn’t happen under the Conservatives have suddenly happened under Labour; things that one would more neatly associate with the former have instead happened under the latter. That can only mean either that the Labour Party has utterly lost its sense of itself, or that the particular party in office simply doesn’t matter, because the Establishment abides.

I think, in fact, all of these statements are true. It has been a “mask off” moment for the Labour Party, and for Keir Starmer himself, and for the Establishment which enables and directs them. The Labour Party has lost its sense of itself — or, to put it less romantically, has been completely repurposed. And the Establishment does abide; no matter which party is in office, things only ever evolve in one direction. And after all, while Starmer’s behaviour casts a bad light on him, he is only Prime Minister in the first place because the Establishment wanted him, not someone who might have reacted to these riots in a different manner. (Boris Johnson is good at stoking war abroad, but not so willing to stoke it at home.)

But in the end it doesn’t really matter. We don’t need to pin the blame on Starmer, Labour, the British Establishment or Davos; they are all one and the same miasma. Yes, the Conservative Party might have reacted differently to the riots, so to some extent we can blame Labour’s ideology or Starmer’s personality, but the pendulum is kept swinging for a reason. One empty suit is shifted out, another is shifted in. Each one might be enthusiastically on-board with the agenda or compelled to go along with it, this being the only variance. And thus the Establishment abides, always getting what it wants against the wishes of the natives, and always degrading and dispossessing them.

August 27, 2024

Was 1974 the worst year in British politics or just the worst year so far?

I wasn’t in the UK in 1974 (although I did spend a couple of dystopian weeks there in January 1979), so I don’t know from personal experience just how bad things were, but as Ed West considers Dominic Sandbrook’s very informative social history Seasons in the Sun, he certainly helps make a strong case for it:

One of my favourite moments from reading Fever Pitch as a teenager was the passage where Nick Hornby and a friend bunk off school to watch Arsenal play West Ham, a game which was being held on a weekday afternoon because there wasn’t enough electricity for the floodlights. Britain was enduring a three-day week due to the energy crisis, and assuming the ground would be empty, Hornby is stunned to find it packed with 60,000 people, all skiving off work, and he recalls his hypocritical juvenile disgust at the idleness of the British public.

The scene encapsulates the comic crapness of that period, one that many of us have enjoyed laughing at with the recent Rest is History series on 1974. I began reading Sandbrook’s book Seasons in the Sun afterwards, from where the material for the series was drawn; the early chapters comprise a highly entertaining account of what he described on the podcast as “the worst year in British politics”. Reassuring, perhaps, for those of us inclined towards pessimism, although to paraphrase Homer Simpson, perhaps it was only the worst year so far.

Nineteen-seventy-four saw two elections, the first of which ended in a hung parliament, with Labour as the largest party, and the second with Harold Wilson winning with a majority of 3. These were fought between parties led by exhausted leaders who had run out of ideas, with a third, the Liberals headed by Jeremy Thorpe, soon to be notorious as a dog killer. Britain had declined from the richest country on the continent to one of the poorest in western Europe, and its economy seemed to be falling apart.

During his troubled four years in office Edward Heath had called a state of emergency several times, culminating in ration cards for petrol and power restrictions. In 1973 Heath had “told his Chancellor, Anthony Barber, to go for broke”, Sandbrook writes: “It was one of the greatest economic gambles in modern history: while credit soared and the money supply boomed, Heath hoped to keep inflation down through an elaborate system of wage and price controls”. By October that year, “his hopes were unravelling at terrifying speed”.

The “Barber boom” led to “house prices surging by 25 per cent in just six months, the cost of imports rocketing and Britain’s trade balance plunging deep into the red”. Yet just a week after Heath had published details of his “Stage Three” incomes policy, “the Arab oil exporters in the OPEC cartel announced a stunning 70 per cent increase in the posted price of oil, punishing the West for its support for Israel. It was a devastating blow to the world economy, but nowhere was its impact greater than in Britain.”

The stock market lost a quarter of its value in just a month, while by January 1974 share prices had fallen by almost half in under two years. Just before Christmas, the government cut spending by 4 per cent, and Labour’s Shadow Chancellor, Denis Healey, “warned his colleagues that Britain stood on the brink of an ‘economic holocaust'”. Nine out of ten people told a Harris poll that “things are going very badly for Britain” and nearly as many foresaw no improvement in the coming year. They turned out to be correct.

Amid trouble with the National Union of Mineworkers, in November 1973 “Heath announced his fifth state of emergency in barely four years. Floodlighting and electric advertising were banned; behind the scenes, the government began printing petrol ration cards. As the railwaymen voted to join the miners in pursuit of higher pay, it seemed that Britain was sliding into darkness. Offices were ordered to turn down their thermostats, while the BBC and ITV were banned from broadcasting after 10.30 at night. On New Year’s Day, with fuel supplies running dangerously low, the entire nation went on a three-day working week.” Happy days.

July 16, 2024

Britain’s Tories – “It is hard to think of any political Party that has so relentlessly thrown away its political mandate”

Lorenzo Warby considers a few of the early lessons that can be drawn from the British general election results:

I dislike the term “the deep state”. It mystifies what is much more straightforward, even bland: how metastasising bureaucracy is undermining the resilience of Western societies and their political systems.

The British Labour Party has won a massive Parliamentary majority in the House of Commons even though its total votes fell: from 10,269,051 in 2019 — 32.1% of total votes — to 9,704,655 in 2024 — 33.7% of total votes. Labour’s massive Parliamentary majority is not a product of enthusiasm for Labour, but the fracturing of the votes of its opponents.

The Scottish National Party (SNP) vote fell dramatically — from 1,242,380 votes in 2019 to 724,758 in 2024. This was largely a casualty of the SNP embracing the genderwoo of Transactivism. Outside some narrow urban enclaves, no one votes for “woke” but, given a genuine opportunity, folk will vote against it. As Scots have.

The Liberal Democrats did very well, as they have a regionally concentrated vote — which, this time, they targeted properly — and disgruntled (posh) Shire Tories will protest vote Lib-Dem. Clearly, lots did.

The Tories did so badly because their already low vote was further reduced by the Reform vote surge. The Reform vote represented voters punishing the Tories for their failure to do anything they had promised. As political scientist Matt Goodwin puts it:

They failed to control our borders.

They failed to lower legal immigration.

They failed to cut taxes and the size of the state.

They failed to take on woke, exposing our children to ideas with no basis in science.

And they failed to level-up the left behind regions.

It is hard to think of any political Party that has so relentlessly thrown away its political mandate.

So, an angry, unhappy electorate (rightfully) punished two governing Parties (Tories and SNP) and has given Labour a massive majority, with little enthusiasm — almost two-thirds of voters voted for someone else — on a relatively low turnout.

There is, however, a deeper institutional issue underlying these results. Why are voters so disgruntled? Why did the Tories fail so spectacularly?

The answer to these questions is a mixture of how institutions have evolved, the development of media culture, the Anywhere-Somewhere divide and technocratic delusions.

Technocratic delusion

The technocratic delusion is multi-layered. It holds that governing is a managerial input-output problem, government bureaucracy simply implements policy, and that politics is not a motivation and coordination problem.

None of these presumptions are true, so technocratic politics fails. It does not connect to voters and does not understand, or grapple with, the actual institutional landscape.

The technocratic delusion is a way for clever people to be spectacularly clueless. Not the only such mechanism in the modern world.

July 12, 2024

The British prison system is over-capacity, and Starmer’s new government has a plan

As Ed West points out, the new Labour government’s plan is to move in a different direction than most Britons were hoping:

“Main gate to the HM Prison Wormwood Scrubs in spring 2013” by Chmee2 is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 .

Britain’s prisons are desperately overcrowded and morale among staff at an all-time low, following years of underfunding by the Conservative government and the inability of the state to build new jails against local opposition.

Now the incoming prime minister says that we have too many prisoners, while new prison minister James Timpson believes the British justice system is “addicted to punishment”, stating that only a third of inmates should be in jail.

The justice secretary, meanwhile, is considering “lowering the automatic release point for prisoners to less than 50 per cent through their sentence”. While currently prisoners serve half their sentences, or two-thirds for some sexual, violent or terror-related offences, the government plans to push the automatic release point to 40 per cent of their terms for those serving less than 4 years, benefitting 40,000 inmates — but not necessarily benefitting the rest of us.

This would be a very unwise move. The majority of prisoners are inside for sexual or other violent crimes, and even restricting early releases to those serving under four years would set free some very dangerous individuals, while previous amnesties of this type have led to huge increases in crime.

The idea that Britain “is addicted to punishment” jars with the sentences regularly handed out even for the most horrendous crimes, and the way that incorrigible criminals are allowed to offend again. This is the subject of a Twitter thread which I began six years ago, in order to highlight how the common belief in the punitive state was mistaken.

As an illustration, and bear in mind that their “sentences” are often twice what they actually served, here are a few cases:

A man who killed his wife in 1981, who was released after a few years and went on to strangle a girlfriend 12 years later, was subsequently freed — and ended up killing a third woman.

There was serial rapist Milton Brown, who was sentenced to 21 years for raping three women – one of whom took her own life – and was released early, only to rape again.

Or Joshua Carney, 28, freed on licence from prison and who just five days later brutally raped a mother and her 14-year-old daughter. He was allowed out despite 47 previous convictions, and now having been convicted of “13 charges including rape, attempted rape, actual bodily harm and theft” he is still eligible for parole in 10 years. Doesn’t sound like a country addicted to punishment.

There was John Harding, who treated a woman “like a rag-doll” when he beat and threatened to kill her after she told him she didn’t want a relationship. Despite terrorising his victim, including wrapping a sheet around her neck, and being in breach of a 30-month community order for a number of offences, including assault and threatening to kill another woman, and having other convictions for theft and criminal damage, he received a sentence of 21 months. As a result, in 2023, Harding was free to rape two women. Now convicted of rape, actual bodily harm, false imprisonment, strangulation and threats to kill, his sentence of 15 years means he could be out in 10.

If you believe that criminals only behave that way because of “systemic racism” or “poverty” or some other form of impersonal forces, you’ll likely also believe that punishment therefore serves no useful purpose and be in favour of all sorts of alternatives. At least until you or someone close to you is a victim of violent crime …

July 11, 2024

On immigration, progressives are following Brecht’s advice to “dissolve the people and elect another”

In the US, Canada, Britain, and most of western Europe the tide of immigration (legal and illegal) never seems to ebb, despite clear indications from the electorates that they’ve had enough. But perhaps progressives in each country are merely taking Bertolt Brecht’s advice for times when the people have forfeited the government’s confidence:

The problem extends far, far beyond merely glutting the labor market and lowering our wage scale, however. See, I’ve explained above why many Republicans go along with the Amnesty Express. But what about the Democrats? What’s in it for them, especially since Big Labor – whose members stand to lose a great deal because of the depression of wage levels – makes up such a prominent part of the Democrat coalition?

What the Democrats stand to win is permanent political power.

See, unlike previous waves of immigration, we are making no effort whatsoever to assimilate current immigrants to our culture and society. Instead, immigrants tend to cluster in indigestible lumps, maintaining their own cultures, languages, and ways from “the old country”. This is doubly true of illegal immigrants, who have managed to turn large swathes of many of our cities into small-scale replicas of Mexico and Morocco. This is even more troublesome because practically all of these immigrants come from places whose histories and traditions are grossly incompatible with our own. These folks don’t know about the idea of protecting life, liberty, and property through a rule of law system, so consequently they don’t CARE about such a system. They’re just here to get jobs or get welfare, for the most part.

In essence, when you import millions of people from socialistic and/or primitive Global South countries, you will end up with a socialistic, primitive Global South country of your own. And that’s what the Democrats are counting on. This is essentially what has been happening with the millions of people coming across our southern border from all over the world.

If the Democrats can get all of the 30-60 million illegals in America amnestied so that they can stay here and start their “path to citizenship”, and can bring in millions more through the various visa processes, then the Democrats are setting themselves up to be able to gain total control in about two decades – which is how long it will take for the children of all these immigrants to join the pool of voters with their parents. Further, they don’t seem to even want to have to wait that long, considering how they are opposing a bill currently before the Congress that would crack down on voting by illegal immigrants. Essentially, the Democrats – who have been unable to convince the current set of American voters to consistently elect them – want to replace us with a new set of voters, one which will vote overwhelmingly for the Democrats every election, up until we reach the point where there aren’t any more elections.

This is why I say that immigration is more important even than abortion or these other issues that people on the Right are so concerned about. Think about it. With 100 million newly-minted Democrat voters, the Democrats will be able to gain permanent control of all branches of government, at all levels, in nearly all of the states. What that means is that they will get to push through their policies at will. That means no more pro-life restrictions on infanticide. No more gun rights. No more religious liberty. No more rollback of the gay agenda. No more tax cuts or spending rollbacks. No more economic liberty. Kiss private property goodbye. THAT’S what the Democrats want – and the only way for them to get it to convince enough idiots in this country to give it to them via immigration, both legal and illegal.

So while conservatives are clawing each other’s eyes out because one candidate or the other isn’t as pro-life as they want them to be, the Democrats are setting up the playing field to replace the current American electorate with a new one from the Third World, complete with all the third world values of corruption and socialism that come with them.

Of course, for “Democrats”, read “Liberals” in Canada, “Labour” in the UK, and so on. The party labels change, but the basic beliefs are remarkably consistent across the western world (and Rishi Sunak’s just-ousted Conservatives were just as committed to open borders and mass immigration as Keir Starmer’s new Labour government).

July 7, 2024

More on the British general election results

At Postcards from Barsoom, John Carter has some further thoughts on the Sunak implosion on the 4th of July:

Sir Keir Starmer speaking to the media outside Number 10 Downing Street, 5 July, 2024.

Picture by Kirsty O’Connor/ No 10 Downing Street via Wikimedia Commons.

The Conservative wipeout was disappointingly not the annihilation that early polls predicted. The Tories were successful in scaring a critical mass of boomers in a last minute get-out-the-vote effort. At the same time, I suspect that some incidents late in the election that were used to paint Reform as raving Nazis were successful in driving down the Reform vote. One such incident involved a marginal Reform candidate caught on microphone being extraordinarily vulgar, who later turned out to be an actor that specialized in playing precisely the sort of character he was portraying for the media, which is of course all rather suspicious.

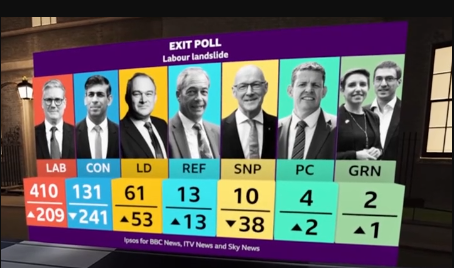

As a result, Reform only got 4 seats. This was less than the 13 that were predicted by the BBC based on exit polling, which prediction was revised to the 4 that Reform in fact won partway through counting, as the models’ Bayesian priors were updated accordingly, no doubt. That said, among those 4 seats is Nigel Farage, who is now a sitting member of Parliament.

That Parliament is now, in all likelihood, in the hands of the weakest massive majority government in its history, and if that’s not true (British history in its entirety being rather extensive), certainly close to it.

Keir Starmer’s Labour has 412 seats of Parliament’s total 650, giving it an unassailable majority. This is not because of a sudden surge in their popularity: their share of the popular vote didn’t budge, from around a third of the population. Turnout was moreover unenthusiastic, about 59% of the population I think, which while not as wince-inducing as the nearly 50% participation that the BBC was claiming throughout most of the counting period, is still nothing to write home about. The total number of people who voted for Labour decreased by 600,000. Labour cannot claim any sort of popular mandate, and they know it.

Not that Labour — or any western political party elected under these circumstances — could be expected to take it into consideration. From their point of view, all that matters is the seats in the House of Commons, and they’ve got them in spades.

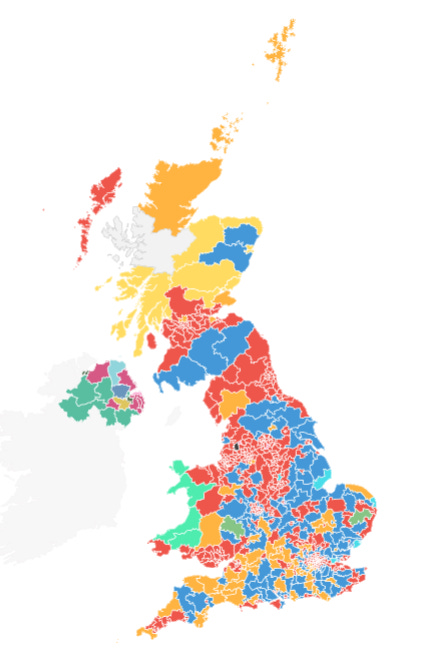

Reform and the Lib Dems were not the only beneficiaries of the Conservative collapse. This can be seen immediately in the crazy quilt of the electoral map, which despite Labour’s two-thirds majority, is planted with the flags of all sorts of weird political tribes.

My favourite part is Northern Ireland, where Sinn Fein held its 7 seats (making it the fifth-largest party after the SNP), and the rest of it is split up in an impenetrable jumble of splinter parties vaguely associated with different reasons for remaining part of the UK and/or the EU. Wales has been painted bright green by Plaid Cymru, the Party of Wales, who doubled their presence in parliament to 4. This is the same number of seats as Reform got, despite Plaid Cymru having gotten just under 200,000 votes, as compared to Reform’s 4.1 million, yet another perversity of first-past-the-post.

To everyone’s disappointment, first-past-the-post did not deliver a seat into the hands of the Monster Raving Loony Party, who received only 5,814 votes, a dismal 0.02% of the total 28.4 million votes cast. I do not know what kind of person votes for the Monster Raving Loony Party, but I bet they are absolutely fascinating. They should consider moving to one of Britain’s remote underpopulated islands, the Orkneys perhaps, where they might just be able to take over a seat. Having a strong, concentrated regional presence seems to be the best way to get members into Parliament in a first-past-the-post system, and having a sitting member for the Monster Raving Loonies would be even funnier than having Nigel in there.

First-past-the-post gets a lot of hate, and I’ve been ripping on it here, but it actually seems well-suited to an island which is shared by a bunch of squabbling ancient tribes. While it tends to produce majorities quite easily due to the winner-take-all nature of the contest within each riding, this also allows areas with strong regional identities to assert a disproportionate presence in parliament, despite getting a measly percentage of the vote. Not that that especially matters, given the aforementioned tendency for the system to hand out crushing jackpot majorities to the dominant players, as it has indeed done once again.

With the sole exception of Reform, there has not been any wave of enthusiasm for any of the parties in parliament. Large numbers of voters simply stayed home, whether tuning it all out or punishing their home parties while failing to see anything they wanted to vote for. It is as though the tide has gone out, exposing the sand and rocks of the sea shore. Whether this is a regular tide, which will gently slosh back in again in time, or a tsunami, remains to be seen. Certainly it feels that the water has receded very far indeed, exposing more of the seafloor’s surface than one normally sees. Say, is that Doggerland over there?

July 6, 2024

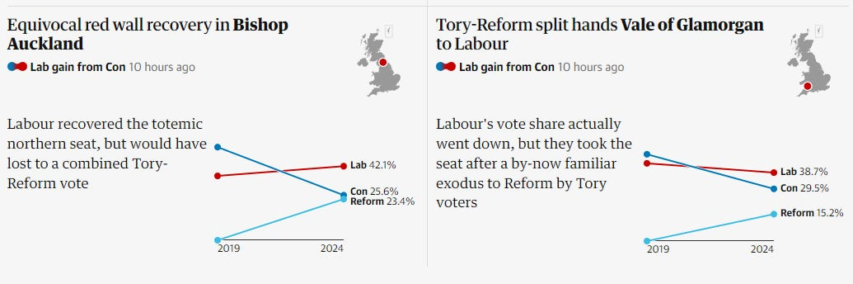

Labour’s “landslide”

I put the scare quotes around the word “landslide” because Labour’s eye-popping total of seats in Parliament was won on a remarkably narrow share of the actual votes cast in the British general election on Thursday (less than Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour party won in 2019). Fratricide on the right allowed a lot of Labour candidates to squeak in the win as the combined Tory/Reform votes would have been more than enough to top Labour.

Labour has won a landslide and the largest swing in British history without even increasing its vote share in England, and winning perhaps only 35% nationally. Its only significant gains in proportional terms were in Scotland, largely at the expense of the SNP, who have suffered catastrophic losses, meaning they are only 1 seat ahead of Sinn Fein, now the largest party in Northern Ireland — who are in turn 3 seats ahead of Reform, the third largest party in Britain by vote.

But these Reform MPs are — as I write — outnumbered by the five pro-Gaza independents, who won seats in Yorkshire, Lancashire, the Midlands and London in reaction to Keir Starmer’s position on Israel. Labour are down an average of 18 points in seats where the Muslim population is 20%, and in seats where that figure is above 25%, they are down 23 percentage points. While Labour lost a huge share of the Muslim vote, what is more worrying is the atmosphere in which this has taken place.

In Birmingham Yardley Jess Phillips held on by 700 votes, and in a remarkably unpleasant – I might even say upsetting, although I’ve only had three hours’ sleep — count she lamented that “This election has been the worst election I have ever stood in”, as she was booed.

“I understand that a strong woman standing up to you is met with such reticence”, she told her antagonists, and described how opponents had filmed a Labour activist in the streets and slashed her tyres, while another was screamed at by a man. She told how Jo Cox’s family had wanted to come and campaign but she couldn’t let them endure it. “Can you throw them out?” she asked the authorities of her hecklers.

There were similar scenes in Birmingham Ladywood as Shabana Mahmood was heckled as she gave her speech, the returning officer pleading with the supporters of independent Ahkmed Yakoob to stop.

Yakoob was described by the Sunday Times‘s Will Lloyd as “the one man in Britain who embodies the way our politics have changed”. He described “a 36-year-old defence solicitor who wears black Prada trainers, a glittering diamond watch, tinted gold-framed sunglasses and Gareth Southgate-like waistcoats. He has 195,000 followers on TikTok, a platform he understands more intuitively than 99 per cent of the politicians in this country. He speaks in clipped, brutal epigrams that sound like they are only ever a few” and “The word ‘genocide’ is never far from his mouth with ‘For Gaza’ printed on his leaflets.”

Labour hung on in Ladywood, a historic constituency in England’s second city where in 1924 Neville Chamberlain very narrowly beat a rising star of the Labour Party called Oswald Mosley.

Gaza independents also narrowly lost Birmingham Hodge Hill by just 1000 votes, and Ilford North, the constituency of Wes Streeting by just 528 votes.

While the media focus was largely engaged in catching out the musing of some of Reform’s less intellectually capable candidates, this other populist revolt has been carried out in an atmosphere of anger and intimidation perhaps not seen in English elections since the days of Rotten Boroughs.

There was police intervention in Oldham last month, Naz Shah MP was abused as a “dirty, dirty Zionist … paid by Friends of Israel”.

Fellow Canadian observer Damian Penny refuses to apologize for his headline “The Sunak Sets over the British Empire” (and I don’t blame him in the slightest):

Canadian readers, stop me if you’ve heard this before: an historically unpopular center-right Tory government heads into an election under a hapless leader running a catastrophically poor campaign and finds that even its traditional support is being badly eroded by an upstart right-wing populist party called Reform.

What happened in Britain on July 4 (weirdly symbolic, that) is not exactly what we experienced in Canada in 1993 – the Tories suffered the worst election result in their history, but they’re left with 119 more seats than the venerable Progressive Conservative party under Twitter-troll-in-waiting Kim Campbell, and at least the outgoing PM managed to hold on to his own seat — but it’s kind of nice to see the Mother Country adopting our traditions for once.

Honestly, 121 seats for Rishi Sunak’s Conservative Party is much better than I’d expected at the start of this campaign. And had it not been for Nigel Farage’s Reform Party, they might have managed a much less embarrassing defeat, because this kind of thing happened many times over last night:

Not everyone who voted Reform defected from the Conservatives – had Farage’s protest party not been on the ballot, many of its supporters would have stayed home or cast their votes for fringe parties and independent candidates — but it might have made the difference between a bad night for the Tories and the worst election in the Tories’ history.

Reform won four seats outright – less than a hyperbolic exit poll predicted, but four more than most observers expected at the start of the campaign. They can’t really affect much at the national level, especially with Keir Starmer’s Labour Party holding an absolutely massive majority of seats in Parliament, but they will make things very difficult for the Conservatives.

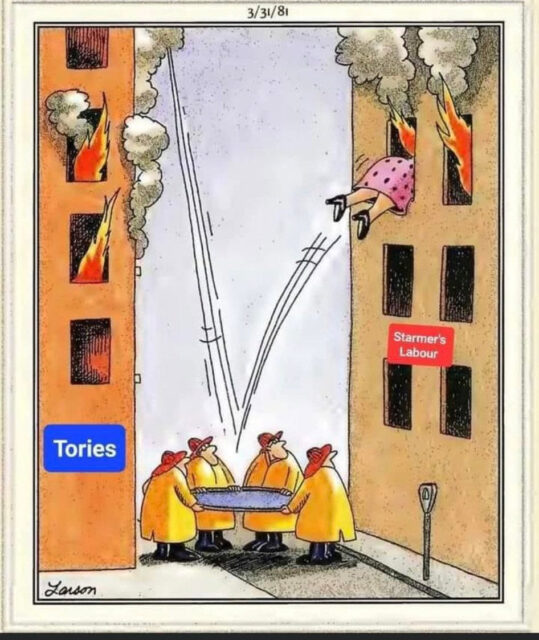

Helen Dale summarized the British general election result in a modified Gary Larson image:

Andrew Doyle points at the disproportional share of the vote won by Nigel Farage’s new Reform UK party compared to the tiny number of seats as a condemnation of the first-past-the-post system (also used here in Canada):

Keir Starmer surely cannot believe his luck. He has achieved a landslide victory by doing very little. He received fewer votes than Jeremy Corbyn in 2019, and yet has ended up with a whopping 412 seats in parliament. The rise of Nigel Farage’s Reform Party has split the right-wing vote and ushered the Conservatives along to their worst ever election result, plunging them to even greater depths than the disastrous election of 1906 under Arthur Balfour.

This was very much a Conservative loss rather than a Labour victory. There is no great enthusiasm for Starmer, and his majority is an indictment of the “First Past The Post” system which, as I have argued previously, should be abandoned in favour of Proportional Representation. It is unsurprising that upon his victory in Clacton-on-Sea, one of Farage’s first public statements has been a commitment to campaign for electoral reform. His party received over 4 million votes and has returned only 5 seats. So that’s 1% of the seats for 14% of the votes. Compare that with the Liberal Democrats, who have 11% of the seats for only 12% of the votes. Most of us will see that there is a problem here, irrespective of our political affiliations.

Worse still, Labour’s victory will empower the culture warriors, those identity-obsessed activists who have accrued so much power already in our major institutions. While the Tory party claimed to be fighting a “war on woke”, all the while enabling the ideology of Critical Social Justice to flourish, leading Labour politicians have cheered on the culture warriors while pretending that they were nothing more than a right-wing fantasy. We have seen some pushback over the past two years in regards to the worst excesses of this movement, but all of this may soon be undone. Now that the identitarians have their political wing in power, we should expect a few years of regression.

In Spiked, Brendan O’Neill thinks the real lesson to be learned from this election is that populism is here to stay:

To see the true quake, you need to look beyond Labour’s mirage-like landslide. As is now becoming clear, Labour has not been swept to power on anything like a wave of public enthusiasm. On the contrary, it won its 412 seats on the second lowest electoral turnout since 1885, and more as a result of people’s exhaustion with the Tories than their love for Sir Keir. No, it is those who refused to vote Labour who have brilliantly unsettled British politics. It is those who took a punt on Nigel Farage’s Reform party who have planted a bomb in the political landscape that will not be easily defused.

For me, the most fascinating stat of the election is the share of the vote received by Labour and the Tories. Labour won around 34 per cent of vote, the Tories around 24 per cent. Let’s leave to one side what a lame landslide it is if only 34 per cent of the people who could be bothered to vote put an X in your box. More striking is the fact that the combined vote share of Labour and the Tories, the parties that have dominated British politics for a century, was 58 per cent. That is staggeringly – and, if you will allow me, hilariously – low.

To put it in historical context: at the last General Election, in 2019, their combined vote share was 75.8 per cent. In 2017 it was even higher: 82.4 per cent. In the elections of the 2000s it hovered around 70 per cent. Why has it now dropped to less than 60 per cent, giving rise to the possibility that in the next few years the two parties that have run this country for decades might see their combined vote drop to less than half of all votes cast? Largely, because of Reform. And a few independents, too. Reform’s vote share is around 14 per cent, enough to shatter the Labour / Tory duopoly and to unravel the two big parties’ arrogant belief that they and they alone have a right to rule.

The speedy turnaround of the Reform revolt was extraordinary. It was only a few weeks ago that Farage ditched his plans to go to America to assist the Trump campaign and instead decided to become leader of Reform. He has now been elected MP for Clacton. Reform has won four seats in total. What’s shocking is that the Liberal Democrats won 71 seats despite getting fewer votes than Reform. The Lib Dems got around 12 per cent of the vote, to Reform’s 14 per cent. That the democratically less popular party of the two will wield far greater power in the Commons is a testament to how busted our first-past-the-post electoral system is. This is unsustainable. It is outright undemocratic.

And yet, even without the parliamentary representation their vote share deserves, Reform has struck a blow for democracy. Their voters, in thinking for themselves and rejecting both the Labour and Tory variety of technocracy, have forcefully created a new opening in political life. They have burst a few of the buckles on the political straitjacket that is our two-party system. The last time this happened was with Farage’s UK Independence Party, in the 2015 General Election, when it won 12.6 per cent of the vote, reducing the Tory / Labour vote share to 67.3 per cent. But where UKIP was mostly a one-issue party, dedicated to getting Britain out of the EU, Reform has broader policy goals. The millions of working-class people who voted for it are saying something very clear indeed: “We want something different”.

June 25, 2024

The ebbing tide of Corbynism

In Spiked, Brendan O’Neill finds the humour in the staggering collapse of the Corbynist wing of the British Labour Party, from being tantalizingly close to forming a government to today’s political knife-fight for a single seat in North London:

Jeremy Corbyn, then-leader of the Labour Party speaking at a rally in Hayfield, Peak District, in 2018.

Photo by Sophie Brown via Wikimedia Commons.

Schadenfreude is an unbecoming emotion, I know. But if you think I am not going to derive at least fleeting pleasure from the fact that the Corbynista movement went from being on the cusp of government to fighting tooth and nail to hold on to one poxy constituency in north London, then you are off your rocker. We must all find mirth wherever we can in this drabbest of elections. And I find mine in the staggering contraction of Corbynism, the almost total collapse of this cause that was once so beloved of every trustafarian Trot, Glasto wanker and they / them fruitloop.

It’s nearly too funny for words. Five years ago, Jeremy Corbyn and his crew were eyeing up Downing Street. They were in the running to run the country. Now they’re entirely concentrated in Islington North. Corbyn once commanded vast crowds of affluent youths at Glastonbury, basking in their posh chant of “Oh, Jeremy Corbyn!”. He had whole armies of time-rich tweeters who put their expensive education to good use by barking at us “gammon” about how “Jez” was “the absolute boy”. Now he can just about rustle up a few score political anoraks to go canvassing for him in a little bit of north London. It would require a heart of stone not to laugh.

Much has changed for “Jez” in the past five years. He was leader of the Labour Party back then. Now he isn’t even a member of the Labour Party. He was suspended in 2020 after he said the scale of Labour’s anti-Semitism problem under his leadership from 2015 to 2020 had been “dramatically overstated for political reasons“. Then he was officially expelled this year after he announced his intention to stand as an independent in Islington North, the constituency he represented for Labour since 1983. The man who wanted to be PM is now fighting for his life to remain an MP. We’ve gone from “socialism in one country” to “socialism in one constituency”.

Die-hard Corbynistas are flocking to Islington North as if it were the Paris Commune under attack from Versailles. They’re beating the streets to plead with constituents to return the absolute boy to parliament in order that socialism might yet live. The list of starry names Corbyn has dragooned to his door-knocking cause reads like a Sky News producer’s rolodex of wankers. Shola Mos-Shogbamimu, anyone? Yes, I’m sure her post-truth bollocks about “all white people [having] white privilege” will go down a treat among the white working classes on the council estates of Archway.

There’s Grace Blakeley, too, a privately educated flapper-girl socialist who thinks flouncing out of a book festival is “collective action“. That’s how she described her decision to withdraw from the Hay Festival over its receipt of funds from the investment management firm, Baillie Gifford. Tweeting “I’ve decided not to go to Hay” is the well-heeled millennial’s Battle of Orgreave. Perhaps Ms Blakeley will compare her class-war wounds with those of some old Irish fella she meets in a pub in Holloway when she’s out electioneering for the boy.