Tenant labor of one form or another may be the single most common form of labor we see on big estates and it could fill both the fixed labor component and the flexible one. Typically tenant labor (also sometimes called sharecropping) meant dividing up some portion of the estate into subsistence-style small farms (although with the labor perhaps more evenly distributed); while the largest share of the crop would go to the tenant or sharecropper, some of it was extracted by the landlord as rent. How much went each way could vary a lot, depending on which party was providing seed, labor, animals and so on, but 50/50 splits are not uncommon. As you might imagine, that extreme split (compared to the often standard c. 10-20% extraction frequent in taxation or 1/11 or 1/17ths that appear frequently in medieval documents for serfs) compels the tenants to more completely utilize household labor (which is to say “farm more land”). At the same time, setting up a bunch of subsistence tenant farms like this creates a rural small-farmer labor pool for the periods of maximum demand, so any spare labor can be soaked up by the main estate (or by other tenant farmers on the same estate). That is, the high rents force the tenants to have to do more labor – more labor that, conveniently, their landlord, charging them the high rents is prepared to profit from by offering them the opportunity to also work on the estate proper.

In many cases, small freeholders might also work as tenants on a nearby large estate as well. There are many good reasons for a small free-holding peasant to want this sort of arrangement […]. So a given area of countryside might have free-holding subsistence farmers who do flexible sharecropping labor on the big estate from time to time alongside full-time tenants who worked land entirely or almost entirely owned by the large landholder. Now, as you might imagine, the situation of tenants – open to eviction and owing their landlords considerable rent – makes them very vulnerable to the landlord compared to neighboring freeholders.

That said, tenants in this sense were generally considered free persons who had the right to leave (even if, as a matter of survival, it was rarely an option, leaving them under the control of their landlords), in contrast to non-free laborers, an umbrella-category covering a wide range of individuals and statuses. I should be clear on one point: nearly every pre-modern complex agrarian society had some form of non-free labor, though the specifics of those systems varied significantly from place to place. Slavery of some form tends to be the rule, rather than the exception for these pre-modern agrarian societies. Two of the largest categories of note here are chattel slavery and debt bondage (also called “debt-peonage”), which in some cases could also shade into each other, but were often considered separate (many ancient societies abolished debt bondage but not chattel slavery for instance and debt-bondsmen often couldn’t be freely sold, unlike chattel slaves). Chattel slaves could be bought, sold and freely traded by their slave masters. In many societies these people were enslaved through warfare with captured soldiers and civilians alike reduced to bondage; the heritability of that status varies quite a lot from one society to the next, as does the likelihood of manumission (that is, becoming free).

Under debt bondage, people who fell into debt might sell (or be forced to sell) dependent family members (selling children is fairly common) or their own person to repay the debt; that bonded status might be permanent, or might hold only till the debt is repaid. In the later case, as remains true in a depressing amount of the world, it was often trivially easy for powerful landlord/slave-holders to ensure that the debt was never paid and in some systems this debt-peon status was heritable. Needless to say, the situation of both of these groups could be and often was quite terrible. The abolition of debt-bondage in Athens and Rome in the sixth and fourth centuries B.C. respectively is generally taken as a strong marker of the rising importance and political influence of the class of rural, poorer citizens and you can readily see why this is a reform they would press for.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Bread, How Did They Make It? Part II: Big Farms”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2020-07-31.

April 17, 2023

QotD: Tenant-farming (aka “sharecropping”) in pre-modern societies

April 10, 2023

QotD: Interaction between “big” farmers and subsistence farmers in pre-modern societies

What our little farmers generally have […] is labor – they have excess household labor because the household is generally “too large” for its farm. Now keep in mind, they’re not looking to maximize the usage of that labor – farming work is hard and one wants to do as little of it as possible. But a family that is too large for the land (a frequent occurrence) is going to be looking at ways to either get more out of their farmland or out of their labor, or both, especially because they otherwise exist on a razor’s edge of subsistence.

And then just over the way, you have the large manor estate, or the Roman villa, or the lands owned by a monastery (because yes, large landholders were sometimes organizations; in medieval Europe, monasteries filled this function in some places) or even just a very rich, successful peasant household. Something of that sort. They have the capital (plow-teams, manure, storage, processing) to more intensively farm the little land our small farmers have, but also, where the small farmer has more labor than land, the large landholder has more land than labor.

The other basic reality that is going to shape our large farmers is their different goals. By and large our small farmers were subsistence farmers – they were trying to farm enough to survive. Subsistence and a little bit more. But most large landholders are looking to use the surplus from their large holdings to support some other activity – typically the lifestyle of wealthy elites, which in turn require supporting many non-farmers as domestic servants, retainers (including military retainers), merchants and craftsmen (who provide the status-signalling luxuries). They may even need the surplus to support political activities (warfare, electioneering, royal patronage, and so on). Consequently, our large landholders want a lot of surplus, which can be readily converted into other things.

The space for a transactional relationship is pretty obvious, though as we will see, the power imbalances here are extreme, so this relationship tends to be quite exploitative in most cases. Let’s start with the labor component. But the fact that our large landholders are looking mainly to produce a large surplus (they are still not, as a rule, profit maximizing, by the by, because often social status and political ends are more important than raw economic profit for maintaining their position in society) means that instead of having a farm to support a family unit, they are seeking labor to support the farm, trying to tailor their labor to the minimum requirements of their holdings.

[…]

The tricky thing for the large landholder is that labor needs throughout the year are not constant. The window for the planting season is generally very narrow and fairly labor intensive: a lot needs to get done in a fairly short time. But harvest is even narrower and more labor intensive. In between those, there is still a fair lot of work to do, but it is not so urgent nor does it require so much labor.

You can readily imagine then the ideal labor arrangement would be to have a permanent labor supply that meets only the low-ebb labor demands of the off-seasons and then supplement that labor supply during the peak seasons (harvest and to a lesser extent planting) with just temporary labor for those seasons. Roman latifundia may have actually come close to realizing this theory; enslaved workers (put into bondage as part of Rome’s many wars of conquest) composed the villa’s primary year-round work force, but the owner (or more likely the villa’s overseer, the vilicus, who might himself be an enslaved person) could contract in sharecroppers or wage labor to cover the needs of the peak labor periods. Those temporary laborers are going to come from the surrounding rural population (again, households with too much labor and too little land who need more work to survive). Some Roman estates may have actually leased out land to tenant farmers for the purpose of creating that “flexible” local labor supply on marginal parts of the estate’s own grounds. Consequently, the large estates of the very wealthy required the impoverished many subsistence farmers in order to function.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Bread, How Did They Make It? Part II: Big Farms”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2020-07-31.

March 30, 2023

“Food insecurity” – one of the neat new benefits of our over-regulated economy

Elizabeth Nickson on how western governments (in her case, the provincial government of British Columbia) are working hand-in-glove with environmental non-governmental organizations to create “food insecurity”:

In Canada, the British Columbia government in order to increase “food security” is handing out $200,000,000 to farmers in the province. Food insecurity, which means crazy high food prices, comes to us courtesy of the sequestration of the vast amounts of oil and gas in the province and the ever increasing carbon tax, which (like a VAT in Europe), as you probably know, is levied at every single step in food production. Add the hand-over-fist borrowing in which the government has indulged for the last 20 years, and you have created your own mini-disaster.

Ever since multinational environmental non-governmental organizations (ENGOs) took over public opinion in the province, our economy has been wrenched from resource extraction to tourism. Tourism is, supposedly, low-impact. The fact that it pays $15 an hour instead of $50 an hour and contributes very much less to the public purse than forestry, mining, farming, ranching, oil and gas, means we have had borrow to pay for health care and schooling. This madness spiked during Covid, and, as in every “post-industrial” state, has contributed to making food very, very much more expensive, despite the fact that British Columbia where I live, is anything but a food desert. We could feed all of Canada and throw in Washington State.

Inflation comes from a real place, it has a source, it is not mysterious and arcane. Regionally, it comes from “green” government decisions. I pay almost 70 percent more for food now than I did five years ago. Of course one cannot know with any confidence how much the real increase is. The Canadian government was caught last week hiding food price statistics and well they might. The Liberal government leads with its “compassion”, blandishing the weak and foolish, hiding the fact that in this vast freezing country they are trying to make it even colder by starving and freezing the lower 50 percent of the population.

Even the Wasp hegemony that ran this country pre-Pierre Elliot Trudeau knew not to try that. But not this crew! It doesn’t touch them. They don’t see and wouldn’t care if they did, about the single mother working in a truck stop on the Trans-Canada Highway, who steals food for her kids because all her money is going towards keeping them warm.

[…]

The region in which I live used to grow all the fruit for the province, now, well good luck with that buddy. Last year under the U.N. 2050 Plan, local government tried to ban farming and even horticulture. That was defeated so hard that the planner who introduced it was fired and the plan scrubbed from the website. Inevitably it will come again in the hopes that citizens or subjects, as we in Canada properly are, have gone back to sleep. U.N. 2050, an advance on 2030, locks down every living organism, and all the other elements that make up life, assigns those elements to multinationals, advised by ENGOs, which can “best decide” how to use them.

If the only tool you have is a hammer, it’s tempting to treat everything as if it were a nail. It is only the most arcane and numerate think tanks who bang on and on about over-regulation and how destructive it is. Regulation is so complex that most people would rather do anything than think about it, much less deconstruct it.

March 23, 2023

QotD: “Slave societies” and “societies with slaves”

Historian Ira Berlin distinguished between “slave societies” and “societies with slaves”, according to the institution’s place in the culture. It could be a large part of the economy of a “society with slaves” — e.g. the northern American colonies circa the Revolution — but it didn’t dominate social, cultural, and institutional life the way it did in a “slave society” (e.g. the Southern colonies). If you’re wondering where this “racist Southerners invented slavery” nonsense that’s been making the rounds on social media came from, look no further, since Berlin’s distinction really only applies to the Antebellum United States — un-free labor* being either effectively unknown, or central, to every even remotely “Western” society well into the modern period.**

So, taking the Antebellum South in particular: Could its economy have survived without slavery? Sure. You don’t have to be a historian to see it, either. Some quick back-of-the-envelope math will suffice. An “agricultural laborer” — surely we agree slaves were that? — in 1860 made, on average, 97 cents a day. Round that up to a dollar, multiply by six days a week, and you get $6 a week. Multiply that by 50 (let’s give everyone two weeks’ vacation) and you get $300 per year. A “prime field hand” in 1860 cost $1600, purchase price. Plus all his “maintenance and upkeep,” year-round, for life. It’s grossly inefficient, what with agriculture being a largely seasonal occupation and all. And that’s before you factor in the mechanization trend that was already well underway at the time of the Civil War.***

Could the South have survived culturally without slavery? Of course not. That’s the whole point of Berlin’s distinction. Neither could any other slave society. The Roman Empire, all of it, is inconceivable without slavery. Here’s the proof: There were lots of freedmen in the Roman Empire. The first thing they did, pretty much without exception, is buy as many slaves as they could afford. Even Athens, the “birthplace of democracy”, depended on slave labor.

* Just to placate any field specialists who want to argue that medieval villeinage wasn’t merely slavery by another name.

** With the (admittedly large) exception of Great Britain, which in true British Imperial style managed to profit hugely from slavery without consciously admitting it. See, for example, Eric Williams’ Capitalism and Slavery, which manages the neat trick of being a Marxist polemic that is (mostly) factually accurate and (largely) argued in good faith. Published in 1944, natch, by a scholar way out on Western Civ’s fringes, but such a thing was possible even for White folks back then — see e.g. the work of Christopher Hill). They’re the other “society with slaves”, and since we’re talking about their spiritual descendants in places like Boston and Providence it’s a distinction without a difference.

*** The fact that Antebellum Northerners thought they couldn’t economically compete with slave labor has nothing to do with the economic reality of slave labor. “Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men” is a nice piece of campaign rhetoric (it was the Republican Party slogan in their first election, 1856), but that’s all it is. And again, you don’t have to be a professional historian to see it. France’s economy was ok after the loss of Saint-Domingue (at one time the most valuable piece of real estate in the world). Great Britain did pretty good, economically, after freeing their slaves in places like Bermuda, Barbados, and Jamaica (again, some of the most valuable real estate in the world in the 18th century).

Severian, “On Slavery”, Rotten Chestnuts, 2020-06-18.

March 5, 2023

QotD: The role of the “big” landowners in pre-modern farming societies

What generally defines our large landholders is their greater access to capital. Now we don’t want to think of capital in the sort of money-denominated, fungible sense of modern finance, but in a very concrete sense: land, infrastructure, animals, and equipment. As we’ll see, it isn’t just that the big men hold more of this capital, but that they hold fundamentally different sorts of capital and often use it very differently.

Of course this begins with land. The thing to keep in mind is that prior to the modern period […] the vast majority of economic activity was the production of the land. That meant that land was both the primary form of holding wealth but also the main income-producing asset. Consequently, larger land holdings are the assets that enable the accumulation of all of the other kinds of capital we’re discussing. By having more land – typically much more land – than is required to feed a single household, these larger farmers can […] produce for markets and trade, enabling them to afford to acquire labor, animals, equipment and so on. Our subsistence farmers of the last post, focused on producing for survival, would be hard-pressed to acquire much further in the way of substantial capital.

The next most important category is generally animals, particularly a plow team […] while our small subsistence farmers may keep chickens or pigs on some small part of the pasture they have access to, they probably do not have a complete plow-team for their own farm […]. Oxen and horses are hideously expensive, both to acquire but also to feed and for a family barely surviving one year to the next, they simply cannot afford them. They also do not have herds of animals (because their small farms absolutely cannot support acres of pasturage) and they probably have limited access to herdsmen generally (that is, transhumant pastoralists moving around the countryside) because those fellows will tend to want to interact with the community leaders who are, as noted above, the large landholders. All of which is to say that while the small farmers may keep a few animals, they do not have access to significantly large numbers of animals (or humans), which matters.

The first impact of having a plow-team is fairly obvious: a plow drawn by a couple of oxen is more effective than a plow pushed by a single human. That means that a plow-team lets the same amount of farming labor sow a larger area of land […]. It also allows for a larger, deeper plow, which in turn plows at a greater depth, which can improve yields […]. You can easily see why, for a landholder with a large farm, having a plow-team is so useful: whereas the subsistence farmer struggles by having too much labor (and too many mouths to feed) and too little land, the big landholder has a lot of land they are trying to get farmed with as little labor as possible. And of course, more to the point, the large landholder has the wealth and acreage necessary to buy and then pasture the animals in the plow-team.

The second major impact is manure. Remember that our farmers live before the time of artificial fertilizer. Crops, especially bulk cereal crops, wear out the nutrients in the soil quite rapidly after repeated harvests, which leaves the farmer two options. The first, standard option, is that the farmer can fallow the field (which also has the advantage of disrupting certain pest life-cycles); depending on the farming method, fallowing may mean planting specific plants to renew the soil’s nutrients when those plants are uprooted and left to return to the soil in the field or it may mean simply turning the field over to wild plants with a similar effect. The second option is using fertilizer, which in this case means manure. Quite a lot of it. Aggressive manuring, particularly on rich soils which have good access to moisture (because cropping also dries out the soil; fallowing can restore that moisture) allows the field to be fallowed less frequently and thus farmed more intensively. In some cases it allowed rich farmland to be continuously cropped, with fairly dramatic increases in returns-to-acreage as a result. And by increasing the nutrients in the soil, it also produces higher yields in a given season.

Now the humans in a farming household aren’t going to generate enough manure on their own to make a meaningful contribution to soil fertility. But the larger landholders generally have two advantages in this sense. First, because their landholdings are large, they can afford to turn over marginal farming ground to pasture for horses, cattle, sheep and so on; these animals not only generate animal products (or prestige, in the case of horses), they also eat the grass and generate manure which can be used on the main farm. The second way to get manure is cities; unlike farming households, cities do produce sufficient quantities of human waste for manuring fields. And where small subsistence farmers are unlikely to be able to buy that supply, large landholders are likely to be politically well-connected enough and wealthy enough to arrange for human waste to be used on their lands, especially for market oriented farms close to cities. And if you just stopped and said, “wait – these guys were paying for human waste?” … yes, yes they sometimes did (and not just for farming! Check out how saltpeter was made, or what a fuller did!).

Finally, there’s the question of infrastructure: tools, machines and storage. The large landholder is the one likely to be able to afford to build things like granaries, mills and so on. Now there is, I want to note, a lot of variation from place to place about exactly how this sort of infrastructure is handled. It might be privately owned, it might be owned by the village, but frequently, the “village mill” was actually owned by the large landholder whose big manor overlooked the village (who may also be the local political authority). And while we’re looking at grain, other agricultural products which don’t store as well or as easily might need to be aggregated for transport to market and sale, a process where the large landholder’s storage facilities, political standing and market contacts are likely to make him the ideal middleman. I don’t want to get too in the weeds (pardon the pun) on all the different kinds of infrastructure (mills for grains, presses for olives, casks for wine) except to note that in many cases the large landholder is the one likely to be able to afford these investments and that smaller farmers growing the same crops nearby might well want to use them.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Bread, How Did They Make It? Part II: Big Farms”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2020-07-31.

February 17, 2023

QotD: Risk mitigation in pre-modern farming communities

Let’s start with the first sort of risk mitigation: reducing the risk of failure. We can actually detect a lot of these strategies by looking for deviations in farming patterns from obvious efficiency. Modern farms are built for efficiency – they typically focus on a single major crop (whatever brings the best returns for the land and market situation) because focusing on a single crop lets you maximize the value of equipment and minimize other costs. They rely on other businesses to provide everything else. Such farms tend to be geographically concentrated – all the fields together – to minimize transit time.

Subsistence farmers generally do not do this. Remember, the goal is not to maximize profit, but to avoid family destruction through starvation. If you only farm one crop (the “best” one) and you get too little rain or too much, or the temperature is wrong – that crop fails and the family starves. But if you farm several different crops, that mitigates the risk of any particular crop failing due to climate conditions, or blight (for the Romans, the standard combination seems to have been a mix of wheat, barley and beans, often with grapes or olives besides; there might also be a small garden space. Orchards might double as grazing-space for a small herd of animals, like pigs). By switching up crops like this and farming a bit of everything, the family is less profitable (and less engaged with markets, more on that in a bit), but much safer because the climate conditions that cause one crop to fail may not impact the others. A good example is actually wheat and barley – wheat is more nutritious and more valuable, but barley is more resistant to bad weather and dry-spells; if the rains don’t come, the wheat might be devastated, but the barley should make it and the family survives. On the flip side, if it rains too much, well the barley is likely to be on high-ground (because it likes the drier ground up there anyway) and so survives; that’d make for a hard year for the family, but a survivable one.

Likewise – as that example implies – our small farmers want to spread out their plots. And indeed, when you look at land-use maps of villages of subsistence farmers, what you often find is that each household farms many small plots which are geographically distributed (this is somewhat less true of the Romans, by the by). Farming, especially in the Mediterranean (but more generally as well) is very much a matter of micro-climates, especially when it comes to rainfall and moisture conditions (something that is less true on the vast flat of the American Great Plains, by the by). It is frequently the case that this side of the hill is dry while that side of the hill gets plenty of rain in a year and so on. Consequently, spreading plots out so that each family has say, a little bit of the valley, a little bit of the flat ground, a little bit of the hilly area, and so on shields each family from catastrophe is one of those micro-climates should completely fail (say, the valley floods, or the rain doesn’t fall and the hills are too dry for anything to grow).

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Bread, How Did They Make It? Part I: Farmers!”, A collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2020-07-24.

February 6, 2023

Food prices going up? Destroying “excess” production? That’s Canada’s Supply Management system working at peak efficiency!

Jon Miltimore reports on recent comments about some of the weird requirements for quota-holding dairy farmers under the Canadian Supply Management system:

Canadian dairy farmer is speaking out after being forced to dump thousands of liters of milk after exceeding the government’s production quota.

In a video shared on TikTok by Travis Huigen, Ontario dairy farmer Jerry Huigen says he’s heartbroken to dump 30,000 liters of milk amid surging dairy prices.

“Right now we are over our quotum, um, it’s regulated by the government and by the DFO (Dairy Farmers of Ontario)”, says Huigen, as he stands beside a machine spewing fresh milk into a drain. “Look at this milk running away. Cause it’s the end of the month. I dump thirty thousand liters of milk, and it breaks my heart.”

Huigen says people ask him why milk prices are so high.

“This here Canadian milk is seven dollars a liter. When I go for my haircut people say, ‘Wow, seven dollars Jerry, for a little bit of milk'”, he says, as he fills a glass of the milk being dumped and drinks. “I say well, you have to go higher up. Cause we have no say anymore, as a dairy farmer on our own farm. They make us dump it.”

[…]

In the United States, the primary regulations are high-level price-fixing, bans on selling unpasteurized milk (which means farmers have to dump their product if dairy processors don’t buy it), and “price gouging” laws that prevent retailers from increasing prices when demand is low, which incentivizes hoarding.

In Canada, the regulations are even worse.

While the price-fixing scheme for milk in the US is incredibly complicated and leaves much to be desired — there’s an old industry adage that says “only five people in the world know how milk is priced in the US and four of them are dead” — in Canada the price is determined by a single bureaucracy: the Canadian Dairy Commission.

The Ottawa-based commission (technically a “Government of Canada Crown Corporation”), which oversees Canada’s entire dairy system (known as Supply Management), raised prices three times in 2022, citing “the rising cost of production”.

Food price inflation remains a serious issue in Canada, but the problem is particularly acute in regards to dairy products, which has seen their annual inflation rate triple over the past year, to almost 12 percent.

If the farmers were doing this sort of price-fixing themselves, it would be illegal. Instead, because it’s the government doing it, it’s mandatory. You aren’t allowed to produce any of the supply-managed products outside the system, and the government helpfully protects Canadians from being “victimized” by cheaper imports by high tariffs on anything competing with supply managed output.

As with any rigged market, the costs of “protecting” the market are diffused among all Canadian consumers, but the benefits are concentrated in the hands of the quota-holders (and the bureaucrats who oversee the system). My issues with the supply management system are one of the “hobby horses” I’ve ridden many times over my nearly 20 years of blogging.

February 5, 2023

QotD: Annual cycles of plenty and scarcity in pre-modern agricultural societies

This brings us to the most fundamental fact of rural life in the pre-modern world: the grain is harvested once a year, but the family eats every day. Of course that means the grain must be stored and only slowly consumed over the entire year (with some left over to be used as seed-grain in the following planting). That creates the first cycle in agricultural life: after the harvest, food is generally plentiful and prices for it are low […] As the year goes on, food becomes scarcer and the prices for it rise as each family “eats down” their stockpile.

That has more than just economic impacts because the family unit becomes more vulnerable as that food stockpile dwindles. Malnutrition brings on a host of other threats: elevated risk of death from injury or disease most notably. Repeated malnutrition also has devastating long-term effects on young children […] Consequently, we see seasonal mortality patterns in agricultural communities which tend to follow harvest cycles; when the harvest is poor, the family starts to run low on food before the next harvest, which leads to rationing the remaining food, which leads to malnutrition. That malnutrition is not evenly distributed though: the working age adults need to be strong enough to bring in the next harvest when it comes (or to be doing additional non-farming labor to supplement the family), so the short rations are going to go to the children and the elderly. Which in turn means that “lean” years are marked by increased mortality especially among the children and the elderly, the former of which is how the rural population “regulates” to its food production in the absence of modern birth control (but, as an aside: this doesn’t lead to pure Malthusian dynamics – a lot more influences the food production ceiling than just available land. You can have low-equilibrium or high-equilibrium systems, especially when looking at the availability of certain sorts of farming capital or access to trade at distance. I cannot stress this enough: Malthus was wrong; yes, interestingly, usefully wrong – but still wrong. The big plagues sometimes pointed to as evidence of Malthusian crises have as much if not more to do with rising trade interconnectedness than declining nutritional standards). This creates yearly cycles of plenty and vulnerability […]

Next to that little cycle, we also have a “big” cycle of generations. The ratio of labor-to-food-requirements varies as generations are born, age and die; it isn’t constant. The family is at its peak labor effectiveness at the point when the youngest generation is physically mature but hasn’t yet begun having children (the exact age-range there is going to vary by nuptial patterns, see below) and at its most vulnerable when the youngest generation is immature. By way of example, let’s imagine a family (I’m going to use Roman names because they make gender very clear, but this is a completely made-up family): we have Gaius (M, 45), his wife, Cornelia (39, F), his mother Tullia (64, F) and their children Gaius (21, M), Secundus (19, M), Julia1 (16, F) and Julia2 (14, F). That family has three male laborers, three female laborers (Tullia being in her twilight years, we don’t count), all effectively adults in that sense, against 7 mouths to feed. But let’s fast-forward fifteen years. Gaius is now 60 and slowing down, Cornelia is 54; Tullia, we may assume has passed. But Gaius now 36 is married to Clodia (20, F; welcome to Roman marriage patterns), with two children Gaius (3, M) and Julia3 (1, F); Julia1 and Julia2 are married and now in different households and Secundus, recognizing that the family’s financial situation is never going to allow him to marry and set up a household has left for the Big City. So we now have the labor of two women and a man-and-a-half (since Gaius the Elder is quite old) against six mouths and the situation is likely to get worse in the following years as Gaius-the-Younger and Clodia have more children and Gaius-the-Elder gets older. The point of all of this is to note that just as risk and vulnerability peak and subside on a yearly basis in cycles, they also do this on a generational basis in cycles.

(An aside: the exact structure of these generational patterns follow on marriage patterns which differ somewhat culture to culture. In just about every subsistence farming culture I’ve seen, women marry young (by modern standards) often in their mid-to-late teens, or early twenties; that doesn’t vary much (marriage ages tend to be younger, paradoxically, for wealthier people in these societies, by the by). But marriage-ages for men vary quite a lot, from societies where men’s age at first marriage is in the early 20s to societies like Roman and Greece where it is in the late 20s to mid-thirties. At Rome during the Republic, the expectation seems to have been that a Roman man would complete the bulk of their military service – in their twenties and possibly early thirties – before starting a household; something with implications for Roman household vulnerability. Check out Rosenstein, op. cit. on this).

On top of these cycles of vulnerability, you have truly unpredictable risk. Crops can fail in so many ways. In areas without irrigated rivers, a dry spell at the wrong time is enough; for places with rivers, flooding becomes a concern because the fields have to be set close to the water-table. Pests and crop blights are also a potential risk factor, as of course is conflict.

So instead of imagining a farm with a “standard” yield, imagine a farm with a standard grain consumption. Most years, the farm’s production (bolstered by other activities like sharecropping that we’ll talk about later) exceed that consumption, with the remainder being surplus available for sale, trade or as gifts to neighbors and friends. Some years, the farm’s production falls short, creating that shortfall. Meanwhile families tend to grow to the size the farm can support, rather than to the labor needs the farm has, which tends to mean too many hands (and mouths) and not enough land. Which in turn causes the family to ride a line of fairly high risk in many cases.

All of this is to stress that these farmers are looking to manage risk through cycles of vulnerability […]

I led in with all of that risk and vulnerability because without it just about nothing these farmers do makes a lot of sense; once you understand that they are managing risk, everything falls into place.

Most modern folks think in terms of profit maximization; we take for granted that we will still be alive tomorrow and instead ask how we can maximize how much money we have then (this is, admittedly, a lot less true for the least fortunate among us). We thus tend to favor efficient systems, even if they are vulnerable. From this perspective, ancient farmers – as we’ll see – look very silly, but this is a trap, albeit one that even some very august ancient scholars have fallen into. These are not irrational, unthinking people; they are poor, not stupid – those are not the same things.

But because these households wobble on the edge of disaster continually, that changes the calculus. These small subsistence farmers generally seek to minimize risk, rather than maximize profits. After all, improving yields by 5% doesn’t mean much if everyone starves to death in the third year because of a tail-risk that wasn’t mitigated. Moreover, for most of these farmers, working harder and farming more generally doesn’t offer a route out of the small farming class – these societies typically lack that kind of mobility (and also generally lack the massive wealth-creation potential of industrial power which powers that kind of mobility). Consequently, there is little gain to taking risks and much to lose. So as we’ll see, these farmers generally sacrifice efficiency for greater margins of safety, every time.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Bread, How Did They Make It? Part I: Farmers!”, A collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2020-07-24.

January 23, 2023

QotD: Rice farming

There are a lot of varieties of rice out there, but the key divide we want to make early is between dry-rice and wet-rice. When we’re talking about “rice cultures” or “rice agriculture”, generally, we mean wet-rice farming, where the rice is partially submerged during its growing. Wild rice, as far as we can tell, began as a swamp-grass and thus likes to have quite a lot of water around, although precisely controlling the water availability can lead the rice to be a lot more productive than it would be in its natural habitat. While there are varieties of rice which can be (and are) farmed “dry” (that is, in unflooded fields much like wheat and barley are farmed), the vast majority of rice farming is “wet”. As with grains, this is not merely a matter of different methods of farming, but of different varieties of rice that have been adapted to that farming; varieties of dry-rice and wet-rice have been selectively bred over millennia to perform best in those environments.

Wet-rice is farmed in paddies, small fields (often very small – some Chinese agronomists write that the ideal size for an individual rice field is around 0.1 hectare, which is just 0.24 acres) surrounded by low “bunds” (small earthwork walls or dykes) to keep in the water, typically around two feet high. Because controlling the water level is crucial, rice paddies must be very precisely flat, leading to even relatively gentle slopes often being terraced to create a series of flat fields. Each of these rice paddies (and there will be many because they are so small) are then connected by irrigation canals which channel and control the water in what is often a quite complex system.

The exact timing of rice production is more complex than wheat because a single paddy often sees two crops in a year and the exact planting times vary between areas; one common cycle on the Yangtze is for a February planting (with a June harvest) followed by a June planting (with a November harvest). In other areas, paddies planted with rice during the first planting might be drained and sown with a different plant entirely (sometimes including wheat) in the intervening time.

The cycle runs thusly: after the heavy rains of the monsoons (if available), the field is tilled (or plowed, but as we’ll see, manual tillage is often more common). The seed is then sown (or transplanted) and the field is, using the irrigation system, lightly flooded, so that the young seedlings grow in standing water. Sometimes the seed is initially planted in a dedicated seed-bed and then transferred to the field, rather than being sown there directly; doing so has a positive impact on yields, but is substantially more labor intensive. The water level is raised as the plant grows; agian this is labor intensive, but increases yields. Just before the harvest the fields are drained out and allowed to dry out, before the crop is harvested and then goes into processing.

Rice is threshed much like grain (more often manually threshed and generally not threshed with flails) to release the seeds, the individual rice grains, from the plant. That is going to free the endosperm of the speed, along with a hull around it and a layer of bran between the two. Hulling was traditionally done by hand-pounding, which frees the seed from the hull, leaving just the endosperm and some of the bran; this is how you get brown rice, which is essentially “whole-grain” rice. While it is generally less tasty, the bran actually has quite a lot of nutrients not present in the calorie-rich endosperm. Whereas white rice is produced by then milling or polishing away the bran to produce a pure, white kernal of the endosperm; it is very tasty, but lacks many of the vitamins that brown rice has.

Consequently, while a diet of mostly brown rice can be healthy, a diet overwhelmingly of white rice leads to Thiamine deficiency, known colloquially as beriberi. My impression from the literature is that this wasn’t as much an issue prior to the introduction of mechanical milling processes for rice. Mechanical milling made producing white rice in quantity cheap and so it came to dominate the diet to the exclusion of brown rice, producing negative health effects for the poor who could not afford to supplement their rice-and-millet diet with other foods, or for soldiers whose ration was in rice. But prior to that mechanical milling, brown rice was all that was available for the poor, which in turn meant less Thiamine deficiency among the lower classes of society.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Bread, How Did They Make It? Addendum: Rice!”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2020-09-04.

January 8, 2023

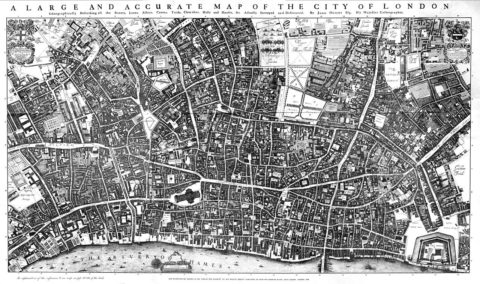

The (historical) lure of London

In the latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes considers the puzzle that was the phenomenol growth of London, even at a time that England had a competitive advantage in agricultural exports to the continent:

… the extraordinary inflow of migrants to London in the period when it grew eightfold — from an unremarkable city of a mere 50,000 souls in 1550, to one of the largest cities in Europe in 1650, boasting 400,000. I’ve written about that growth a few times before, especially here. It may not sound like much today, but it has to be one of the most important facts in British economic history. It is, in my view, the first sign of an “Industrial Revolution”, and certainly the first indication that there was something economically weird about England. It requires proper explanation.

In brief, the key question is whether the migrants to London — almost all of whom came from elsewhere in England — were pushed out of the countryside, thrown off their land thanks to things like enclosure, or pulled by London’s attractions.

I think the evidence is overwhelmingly that they were pulled and not pushed:

- The English rural population continued to grow in absolute terms, even if a larger proportion of the total population made their way to London. The population working in agriculture swelled from 2.1 million in 1550 to about 3.3 million in 1650. Hardly a sign of widespread displacement.

- As for the people outside of agriculture, many remained in or even fled to the countryside. In the 1560s, for example, York’s textile industry left for the countryside and smaller towns, pursuing lower costs of living and perhaps trying to escape the city’s guild restrictions. In 1550-1650, the population engaged in rural industry — largely spinning and weaving in their homes — swelled from about 0.7 to 1.5 million. Again, it doesn’t exactly suggest rural displacement. If anything, the opposite.

- There were in fact large economic pressures for England to stay rural. England for the entire period was a net exporter of grain, feeding the urban centres of the Netherlands and Italy. The usual pattern for already-agrarian economies, when faced with the demands of foreign cities, is to specialise further — to stay agrarian, if not agrarianise more. It’s what happened in much of the Baltic, which also fed the Dutch and Italian cities. Despite the same pressures for England to agrarianise, however, London still grew. To my mind, it suggests that London had developed an independent economic gravity of its own, helping to pull an ever larger proportion of the whole country’s population out of agriculture and into the industries needed to supply the city.

- As for the supposed push factor, enclosure, the timing just doesn’t fit. Enclosure had been happening in a piecemeal and often voluntary way since at least the fourteenth century. By 1550, before London’s growth had even begun, by one estimate almost half of the country’s total surface had already been enclosed, with a further quarter gradually enclosed over the course of the seventeenth century. A more recent estimate suggests that by 1600 already 73% of England’s land had been enclosed. As for the small remainder, this was mopped up by Parliament’s infamous enclosure acts from the 1760s onwards — much too late to explain London’s population explosion.

- Perhaps most importantly, people flocked specifically to London. In 1550 only about 3-4% of the population lived in cities. By 1650, it was 9%, a whopping 85% of whom lived in London alone. And this even understates the scale of the migration to the city, because so many Londoners were dropping dead. It was full of disease in even a good year, and in the bad it could lose tens of thousands — figures equivalent or even larger than the entire populations of the next largest cities. Waves upon waves of newcomers were needed just to keep the city’s population stable, let alone to grow it eightfold. In the seventeenth century the city absorbed an estimated half of the entire natural increase in England’s population from extra births. If England’s urbanisation had been thanks to rural displacement, you’d expect people to have flocked to the closest, and much safer, cities, rather than making the long trek to London alone.

It’s this last point that I’ve long wanted to flesh out some more. The further people were willing to trek to London, the more strongly it suggests that the city had a specific pull. I’d so far put together a few dribs and drabs of evidence for this. Whereas towns like Sheffield drew its apprentices from within a radius of about twenty miles, London attracted young people from hundreds of miles away, with especially many coming from the midlands and the north of England. Indeed, London’s radius seems to have shrunk over the course of the seventeenth century, suggested that they came from further afield during the initial stages of growth. Records of court witnesses also suggest that only a quarter of men in some of London’s eastern suburbs were born in the city or its surrounding counties.

October 11, 2022

Growing grapes for wine

A guest post at Founding Questions from Allen discusses his many years of growing grapes:

“Pelee Island winery” by John Kannenberg is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

I grew grapes for wine, the noble Vitis Vinifera, for close to 30 years. My heart went out of it when I saw the advent of celebrity wine producers. I could stomach the idea of box wine for women with their cats, after all what else did they have, but the very idea that celebrity itself might indicate discernment or ability was a bridge too far for me.

A good wine can enhance a meal. In fact given any other choice I will choose water with lemon if a decent wine is not available. The acid in the wine, or from the lemon, keeps the palate clear and lets you get more flavor out of a well done meal. Then there is the allure, “why yes I grow my own grapes and make my own wine my dear, care for a glass?” If there is a better way to get a lady to throw her panties at a farmer I don’t know what it is. Oh, and that is FNG, that country song, “She Thinks My Tractor’s Sexy”. No she doesn’t, you damn dope.

I know it sounds trite but good wine starts in the dirt and everything in the dirt ends up in the wine. I had sandy, rocky soil with minimal amounts of organic material. Vines need to struggle to make good wine grapes. I did fertilize but with composted organic material and a mixture of manures. If your manure still contain some amount of ammonia in it the wine will have an interesting bouquet so patience grasshopper, give it 2-3 years to compost well. Watering, I always drip irrigated but sparingly. If you’ve got city water its treatment chemicals will end up in the wine so avoid it as much as possible. I had my own deep water wells so I didn’t have that worry. It’s the same with pest treatments. I planted a certain type of tree near the vineyard that Ladybugs were partial to. Ladybugs do a number on most common insect pests.

So you’ve got your dirt now what? Dig son dig. My preferred vine and row spacing was 8 feet by 8 feet, 8 feet between vines with rows 8 feet apart. I dug a trench approximately 3 feet wide by 3 feet deep for each row of vines. Before you ask, yes I did it by hand. Machinery can actually make things worse as it can compact the soil to rock hard consistency where it isn’t digging. The idea here is to get the vines’ roots to run deep and spread. If your soil is especially compacted a power auger is useful to break up the soil.

Next up you need a trellis because grapes require a lot of support. I used a four wire trellis with two arms to spread the canopy out. The more leaf area you have the more photosynthesis and consequently higher growth you will have. It also will drive the acid sugar balance in the grapes. You’ll have to experiment with it to find out what works best for your location and microclimate. Fortunately you have that 4 to 5 years before you get a good crop.

October 1, 2022

“Father” – Fritz Haber – Sabaton History 113 [Official]

Sabaton History

Published 29 Sept 2022Fritz Haber is a controversial historical figure. He was responsible for scientific advances that fed billions, yet he created weapons of mass destruction that filled millions with terror. This is his story.

(more…)

September 22, 2022

California’s Central Valley of despair

At Astral Codex Ten, Scott Alexander wonders why California’s Central Valley is in such terrible shape — far worse than you’d expect even if the rest of California is looking a bit curdled:

Here’s a topographic map of California (source):

You might notice it has a big valley in the center. This is called “The Central Valley”. Sometimes it also gets called the San Joaquin Valley in the south, or the the Sacramento Valley in the north.

The Central Valley is mostly farms — a little piece of the Midwest in the middle of California. If the Midwest is flyover country, the Central Valley is drive-through country, with most Californians experiencing it only on their way between LA and SF.

Most, myself included, drive through as fast as possible. With a few provisional exceptions — Sacramento, Davis, some areas further north — the Central Valley is terrible. It’s not just the temperatures, which can reach 110°F (43°C) in the summer. Or the air pollution, which by all accounts is at crisis level. Or the smell, which I assume is fertilizer or cattle-related. It’s the cities and people and the whole situation. A short drive through is enough to notice poverty, decay, and homeless camps worse even than the rest of California.

But I didn’t realize how bad it was until reading this piece on the San Joaquin River. It claims that if the Central Valley were its own state, it would be the poorest in America, even worse than Mississippi.

This was kind of shocking. I always think of Mississippi as bad because of a history of racial violence, racial segregation, and getting burned down during the Civil War. But the Central Valley has none of those things, plus it has extremely fertile farmland, plus it’s in one of the richest states of the country and should at least get good subsidies and infrastructure. How did it get so bad?

First of all, is this claim true?

I can’t find official per capita income statistics for the Central Valley, separate from the rest of California, but you can find all the individual counties here. When you look at the ones in the Central Valley, you get a median per capita income of $21,729 (this is binned by counties, which might confuse things, but by good luck there are as many people in counties above the median-income county as below it, so probably not by very much). This is indeed lower than Mississippi’s per capita income of $25,444, although if you look by household or family income, the Central Valley does better again.

Of large Central Valley cities, Sacramento has a median income of $33,565 (but it’s the state capital, which inflates it with politicians and lobbyists), Fresno of $25,738, and Bakersfield of $30,144. Compare to Mississippi, where the state capital of Jackson has $23,714, and numbers 2 and 3 cities Gulfport and Southhaven have $25,074 and $34,237. Overall Missisippi comes out worse here, and none of these seem horrible compared to eg Phoenix with $31,821. Given these numbers (from Google), urban salaries in the Central Valley don’t seem so bad. But when instead I look directly at this list of 280 US metropolitan areas by per capita income, numbers are much lower. Bakersfield at $15,760 is 260th/280, Fresno is 267th, and only Sacramento does okay at 22nd. Mississippi cities come in at 146, 202, and 251. Maybe the difference is because Google’s data is city proper and the list is metro area?

Still, it seems fair to say that the Central Valley is at least somewhat in the same league as Mississippi, even though exactly who outscores whom is inconsistent.

September 3, 2022

The impact of the first wave of globalization

In the latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes considers the world in terms of trade before and after the transportation revolution which changed long-distance trade from primarily luxury goods to commodities for the mass market:

Long-distance trade has of course been common since ancient times. Archaeologists often find Byzantine-made glassware from the sixth century all the way out in India, China, and even Japan. Or beads from seventh-century Southeast Asia all the way out in Libya, Spain, and even Britain. Yet such long-distance trades often involved goods that were entirely unique to particular areas — gems, spices, indigo, coffee, tea — or were sufficiently valuable to make the high costs of transportation worthwhile, such as expert-made glassware, silks, and muslin cloths with impossibly high thread counts. Long-distance trade may have been ancient but was restricted to luxuries. It did not involve the everyday goods of life.

That all changed, however, when the innovations of the sixteenth to the nineteenth centuries caused transportation costs to dramatically fall. With better sailing ships, canals, and navigational techniques, followed by better roads, railways, refrigeration, steam power, and dynamite (which meant railways could cross mountain ranges, canals could link oceans, and new deep-water ports could be dug), it was soon profitable to transport even the cheapest and bulkiest of goods over vast distances — goods like meat, coal, and grain.

The entire world was brought into a single market, in which even the bulkiest commodities of each continent were suddenly in direct competition with one another. The decisions of farmers in Ukraine, for example, in the nineteenth century came to affect the farmers in America, China, India, or even Australia, and all of them vice versa. The prices of commodities all over the world thus converged to similar levels, falling in some places, but rising in the economies that had previously been too distant from the ready markets of the industrialised nations.

The result was what economic historians call a terms-of-trade boom, with the more agrarian economies’ commodity exports becoming more valuable relative to manufactured imports. Thus, their grain, raw fibres, minerals, and ores suddenly bought many more foreign manufactures like textiles. Countries that specialised in commodities thus specialised even further, devoting even more of their workers, resources and capital to extracting them. They were incentivised to extend their frontiers — to put more of the wilderness under pasture or plough, and to dig deeper for the mineral wealth beneath their feet.

Meanwhile, for the industrial economies, the opposite happened. By gaining access to many more and cheaper sources of raw resources and food, they were able to make their own manufactured exports cheaper too. And this, in turn, further exacerbated the terms-of-trade boom among their newly globalised commodity suppliers. As the great Saint-Lucian economist Sir W. Arthur Lewis put it, the world in the late nineteenth century separated into an increasingly industrialised “core”, fed by an increasingly farming- and mining-focused “periphery”.

Much has changed in the century that followed, and some of the old core/periphery distinctions have moved or entirely broken down. But the world has remained globalised. Even in periods of higher tariffs, like between the world wars, no amount of protectionism was able to counteract or undo the effects of the dramatic drop in global transportation costs. With the advent of telegraphs, telephones, fax machines, and now the Internet, even many services are becoming globalised as well — a process likely sped up by the pandemic. Those who can easily work from home will increasingly, like nineteenth-century workers the world over, find themselves either the victims or beneficiaries of global price convergence. (Incidentally, I’m not convinced that the very services-heavy economies of Europe or North America are even remotely prepared for this, to the extent that they can prepare at all for what is the economic equivalent of a planetary-scale force of nature.)

August 28, 2022

Why do millions of people try to get into the US from Central and South America?

Elizabeth Nickson on what is driving so many people to leave their homes and trek north to the US (and, to a much lesser extent, Canada):

Mostly they are coming because Black Rock, the UN, the WEF are grabbing their lands, the more fertile the better, driving them from those lands and sticking them into tenement cities where they have to scratch like chickens for a living. Agenda 2030 is ravening under the radar in the US and Canada, where “civil society” in the pay of the government and environmental NGOs funded by oligarchs, is taking as much land and as many resources as possible out of the productive economy and shoving it into the land banks of BlackRock.

In the south, it’s not surreptitious. It is state policy to destroy their lives, to take their ancestral lands, whether it’s 40 acres or a half acre and leave them begging by the side of the road.

Climate Change is a complex financial mechanism which under the guise of “saving the planet”, is meant to save the predator class.

Which is not only morally bankrupt, but is dealing with a level of government and corporate debt that they know they cannot sustain. In the healthiest economy in the world, the US, all profits now are coming from either some mechanism of government subsidy – the $6 Trillion of the Covid catastrophe – or Collateralized Default Obligations. For instance right now Penguin is in court attempting to buy Random House. Why? Because they can borrow money to do that, buy back some of their stock and pay their shareholders. It will mean middle managers will lose their jobs, and marginal books will not be published, but the ravening maw of Jamie Diamond and Larry Fink will be satiated. For the moment. There is no other reason. Growth, real growth has stalled in every single enterprise.

This is how it works at the top of the class pyramid:

Last week on my island we were treated to the spectacle of well-heeled, highly educated, well-spoken older men and women arguing that the impoverished elderly, the young, and families starting out should not have housing because of climate change. Our island is 74 square miles with 10,000 residents. That means we have one resident per five acres.

Our government, the trust, had proposed the use of accessory buildings, brought up to code, for long-term rentals.

The extreme form of land conservation we practice has meant that housing prices have skyrocketed, so only the rich and the well-pensioned can afford to live here. A thousand or so working age people manage to make a living, generally via remote work. We have no staff for the schools, hospitals, businesses, restaurants. They cannot afford to live here.

About 200 people on our islands, mostly in their 70s and 80s, tightly aligned with the hysterical wing of the environmental movement work the process to stop any growth. Every new resident who pulls a permit is visited and threatened by a by-law officer. The woman who instigated this specific weapon, a former enviro bureaucrat from LA, demanded full time by-law officers for years until she won, after which she fought for aggressive enforcement.

With this one act, she set islanders against each other, creating conflict where there was none. This too is deliberate. A community divided is easily controlled.

Ring any bells?