Tasting History with Max Miller

Published 25 Oct 2022

(more…)

October 26, 2022

Sin Eaters & Funeral Biscuits

September 14, 2022

QotD: The Wars of Religion and the (eventual) Peace of Westphalia

Thomas Hobbes blamed the English Civil War on “ghostly authority”. Where the Bible is unclear, the crowd of simple believers will follow the most charismatic preacher. This means that religious wars are both inevitable, and impossible to end. Hobbes was born in 1588 — right in the middle of the Period of the Wars of Religion — and lived another 30 years after the Peace of Westphalia, so he knew what he was talking about.

There’s simply no possible compromise with an opponent who thinks you’re in league with the Devil, if not the literal Antichrist. Nothing Charles I could have done would’ve satisfied the Puritans sufficient for him to remain their king, because even if he did everything they demanded — divorced his Catholic wife, basically turned the Church of England into the Presbyterian Kirk, gave up all but his personal feudal revenues — the very act of doing these things would’ve made his “kingship” meaningless. No English king can turn over one of the fundamental duties of state to Scottish churchwardens and still remain King of England.

This was the basic problem confronting all the combatants in the various Wars of Religion, from the Peasants’ War to the Thirty Years’ War. No matter what the guy with the crown does, he’s illegitimate. It took an entirely new theory of state power, developed over more than 100 years, to finally end the Wars of Religion. In case your Early Modern history is a little rusty, that was the Peace of Westphalia (1648), and it established the modern(-ish) sovereign nation-state. The king is the king because he’s the king; matters of religious conscience are not a sufficient casus belli between states, or for rebellion within states. Cuius regio, eius religio, as the Peace of Augsburg put it — the prince’s religion is the official state religion — and if you don’t like it, move. But since the Peace of Westphalia also made heads of state responsible for the actions of their nationals abroad, the prince had a vested interest in keeping private consciences private.

I wrote “a new theory of state power”, and it’s true, the philosophy behind the Peace of Westphalia was new, but that’s not what ended the violence. What did, quite simply, was exhaustion. The Thirty Years’ War was as devastating to “Germany” as World War I, and all combatants in all nations took tremendous losses. Sweden’s king died in combat, France got huge swathes of its territory devastated (after entering the war on the Protestant side), Spain’s power was permanently broken, and the Holy Roman Empire all but ceased to exist. In short, it was one of the most devastating conflicts in human history. They didn’t stop fighting because they finally wised up; they stopped fighting because they were physically incapable of continuing.

The problem, though, is that the idea of cuius regio, eius religio was never repudiated. European powers didn’t fight each other over different strands of Christianity anymore, but they replaced it with an even more virulent religion, nationalism.

Severian, <--–>”Arguing with God”, Rotten Chestnuts, 2020-01-20.

September 13, 2022

QotD: J.R.R. Tolkien’s childhood and schooling

One reason highbrow people dislike The Lord of the Rings is that it is so backward-looking. But it could never have been otherwise. For good personal reasons, Tolkien was a fundamentally backward-looking person. He was born to English parents in the Orange Free State in 1892, but was taken back to the village of Sarehole, north Worcestershire, by his mother when he was three. His father was meant to join them later, but was killed by rheumatic fever before he boarded ship.

For a time, the fatherless Tolkien enjoyed a happy childhood, devouring children’s classics and exploring the local countryside. But in 1904 his mother died of diabetes, leaving the 12-year-old an orphan. Now he and his brother went to live with an aunt in Edgbaston, near what is now Birmingham’s Five Ways roundabout. In effect, he had moved from the city’s rural fringes to its industrial heart: when he looked out of the window, he saw not trees and hills, but “almost unbroken rooftops with the factory chimneys beyond”. No wonder that from the moment he put pen to paper, his fiction was dominated by a heartfelt nostalgia.

Nostalgia was in the air anyway in the 1890s and 1900s, part of a wider reaction against industrial, urban, capitalist modernity. As a boy, Tolkien was addicted to the imperial adventure stories of H. Rider Haggard, and it’s easy to see The Lord of the Rings as a belated Boy’s Own adventure. An even bigger influence, though, was that Victorian one-man industry, William Morris, inspiration for generations of wallpaper salesmen. Tolkien first read him at King Edward’s, the Birmingham boys’ school that had previously educated Morris’s friend Edward Burne-Jones. And what Tolkien and his friends adored in Morris was the same thing you see in Burne-Jones’s paintings: a fantasy of a lost medieval paradise, a world of chivalry and romance that threw the harsh realities of industrial Britain into stark relief.

It was through Morris that Tolkien first encountered the Icelandic sagas, which the Victorian textile-fancier had adapted into an epic poem in 1876. And while other boys grew out of their obsession with the legends of the North, Tolkien’s fascination only deepened. After going up to Oxford in 1911, he began writing his own version of the Finnish national epic, the Kalevala. When his college, Exeter, awarded him a prize, he spent the money on a pile of Morris books, such as the proto-fantasy novel The House of the Wolfings and his translation of the Icelandic Volsunga Saga. And for the rest of his life, Tolkien wrote in a style heavily influenced by Morris, deliberately imitating the vocabulary and rhythms of the medieval epic.

Dominic Sandbrook, “This is Tolkien’s world”, UnHerd.com, 2021-12-10.

September 6, 2022

Add the traditional English pub to the endangered list

There is nothing to match the warm, cozy comfort of a proper English pub*, especially on those cold, wet days as evening falls. Traditional pubs have been struggling for some time as British preferences in entertainment, drinking, and dining have become more cosmopolitan over the years. The raw numbers of pubs has declined year-over-year for decades, but it’s looking like the winter of 2022/23 may be the worst time for pubs in living memory:

“The Prospect of Whitby ; Pub London” by Loco Steve is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0 .

Simon Pegg’s wise counsel in Shaun of the Dead – “Go to the Winchester, have a nice, cold pint, and wait for all this to blow over” – has long been shared in GIF form whenever a new crisis springs into view.

Chillingly, this time next year, that may no longer be an option. To the Great British pub, the winter energy crisis represents an existential threat. And on the back of two years drifting in purgatory under lockdown, many pubs are facing a war of extermination.

The trade publication for pubs, the Morning Advertiser, makes for especially grim reading at the moment. Its pages are dominated by the energy crisis. It suggests that without urgent government intervention, more than 70 per cent of existing licensed premises will not survive the winter.

One “wet-led” pub – that is, a pub-pub (one that relies on the sale of alcohol to remain viable, rather than on burger stacks and artisan chips served on a slate hubcap) – illustrates this plight all too clearly. Until this summer, it had been paying 14p per electricity unit on a fixed energy contract. But it has now been quoted 83p a unit. It is hard to imagine any cost that could rise so vertically without dealing a mortal blow to a business balanced on the edge of viability. And it’s not as if heating and energy are optional extras during the winter. This is not a thriller, this is a snuff movie.

Pubs have always faced challenges, of course, going right back to the Civil War and the mirthless interregnum. Thanks to Cromwell’s war on harmless pastimes – such as bear-baiting, whoring and dice – you will rarely see him honoured on pub signs in the way you see a Royal Oak or a King’s Arms.

The First World War famously saw the introduction of last orders. This was to keep munitions workers working. It was one of those temporary, emergency measures that, like income tax, proved oddly barbed once in the flesh of the state. As the 20th century wore on, rationing and oil shocks tightened belts. And then, under Thatcher, the rise of restaurants, wine bars and other sub-pub drinking options diffused the economic benefit of those re-loosened belts.

Drink-driving legislation and smoking bans delivered a slow-motion one-two that left many well-established premises, especially in rural locations, reeling. And in the background, the steady drip-drip of anti-drinking propaganda from bodies such as Public Health England (now rebranded as the Health Security Agency) has done its damage, too. The public-health lobby sees drinking only in terms of abuse, while ignoring the social benefits, the knitting-together, the public mental health of England that the public house affords.

* The Scots and the Welsh may have issues with this, but based on my experiences of drinking and dining in pubs in all three countries, it’s the English pub by a country mile. Welsh pubs can be pleasant, but Scottish pubs outside Edinburgh remind me of grim old Ontario bars back when Ontario was still just emerging from the post-Prohibition no-fun-on-Sunday Orange Lodge era (“We’ll let you drink, but you must be made to feel guilty for it!”).

August 30, 2022

Barbarian Europe: Part 10 – The Vikings and the End of the Invasions

seangabb

Published 5 Sep 2021In 400 AD, the Roman Empire covered roughly the same area as it had in 100 AD. By 500 AD, all the western provinces of the Empire had been overrun by barbarians. Between April and July 2021, Sean Gabb explored this transformation with his students. Here is one of his lectures. All student contributions have been removed.

(more…)

August 24, 2022

QotD: Cromwell dismisses the “Rump Parliament”

It is high time for me to put an end to your sitting in this place, which you have dishonored by your contempt of all virtue, and defiled by your practice of every vice.

Ye are a factious crew, and enemies to all good government.

Ye are a pack of mercenary wretches, and would like Esau sell your country for a mess of pottage, and like Judas betray your God for a few pieces of money.

Is there a single virtue now remaining amongst you? Is there one vice you do not possess?

Ye have no more religion than my horse. Gold is your God. Which of you have not bartered your conscience for bribes? Is there a man amongst you that has the least care for the good of the Commonwealth?

Ye sordid prostitutes have you not defiled this sacred place, and turned the Lord’s temple into a den of thieves, by your immoral principles and wicked practices?

Ye are grown intolerably odious to the whole nation. You were deputed here by the people to get grievances redressed, are yourselves become the greatest grievance.

Your country therefore calls upon me to cleanse this Augean stable, by putting a final period to your iniquitous proceedings in this House; and which by God’s help, and the strength he has given me, I am now come to do.

I command ye therefore, upon the peril of your lives, to depart immediately out of this place.

Go, get you out! Make haste! Ye venal slaves be gone! So! Take away that shining bauble there, and lock up the doors.

In the name of God, go!

Oliver Cromwell, speaking to the so-called “Rump” Parliament, 1653-04-20.

August 8, 2022

Barbarian Europe: Part 6 – The Birth of England

seangabb

Published 4 Aug 2021In 400 AD, the Roman Empire covered roughly the same area as it had in 100 AD. By 500 AD, all the Western Provinces of the Empire had been overrun by barbarians. Between April and July 2021, Sean Gabb explored this transformation with his students. Here is one of his lectures. All student contributions have been removed.

(more…)

July 23, 2022

Barbarian Europe: Part 3 – Barbarism and Christianity

seangabb

Published 1 May 2021In 400 AD, the Roman Empire covered roughly the same area as it had in 100 AD. By 500 AD, all the Western Provinces of the Empire had been overrun by barbarians. Between April and July 2021, Sean Gabb explored this transformation with his students. Here is one of his lectures. All student contributions have been removed.

(more…)

July 20, 2022

Climate change is nothing new, and it was warmer in England for a few hundred years in the Middle Ages

If you’ve been reading the blog for a while, you’ll have noticed that I’m not a fan of trying to panic people about climate change … catastrophism just isn’t my thing. I certainly don’t deny that climate change happens and I agree that it is happening now, but I’m highly skeptical that human action has more than a minor influence compared to the ups and downs of long-term climate shifts driven by natural forces. Ed West has a thumbnail sketch of just how much the European (and especially English) climate change impacted ordinary people during the Middle Ages:

Chart from the Journal of Quaternary Science Reviews showing Greenland ice core data over the last 10,000 years. At the end of the Minoan Warming came the Bronze Age Collapse, after the Roman Warming came the fall of the western Roman Empire.

The climate is changing, with all that entails, something we’ve known about for several decades now. Among the early proponents of the theory of climate change was mid-century climatologist Hubert Lamb, who spent most of his career at the Met Office and during the course of his studies made a curious historical discovery.

It was once widely believed that climate remained relatively stable over recorded history, civilisational lifespans being too brief to see such grand changes. But while looking into medieval chroniclers, Lamb was struck by the numerous references to vineyards in England, some as far as the midlands. As long as anyone had ever remembered, the country had been too cold to grow wine, except in tiny pockets of Sussex which occasionally produced almost-drinkable white.

William of Malmesbury, living in the 12th century, observed of his native Wiltshire that “in this region the vines are thicker, the grapes more plentiful and their flavour more delightful than in any other part of England. Those who drink this wine do not have to contort their lips because of the sharp and unpleasant taste, indeed it is little inferior to French wine in sweetness.” How could that have been?

Lamb concluded that Europe must have been considerably warmer during the Middle Ages, and in 1965 produced his great study outlining the theory of the Medieval Warm Period; this posited that Europe was at its hottest in the High Middle Ages (1000-1300) and then became unusually cool between 1500 and 1700.

Since then, Lamb’s thesis has been reinforced by analysis of pollen in peat bogs, as well as the radioactive isotope Carbon-14 found in tree rings (the less sun, the more Carbon-14). In Medieval Europe, every summer was a hot girl summer — and tiny changes could make earth-shattering differences.

The people of Europe enjoyed that extended period of warmer weather for about 300 years, then things suddenly got far worse:

Across Europe, people must have noticed a change. Farmers in the Saastal Valley in Switzerland were probably the first to observe what was happening, back in the 1250s, when the Allalin Glacier began to flow down the mountain. Surviving plant material from Iceland suggests an abrupt decrease in the temperature from 1275 — and, as Rosen points out, a reduction of one degree made a harvest failure seven times more likely. From 1308 England saw four cold winters in succession; the Thames froze, chroniclers recalling dogs chasing rabbits across the icy surface for the first time.

As with many things, change was gradual, until it was dramatic, for then came the disastrous year of 1315. The Chronicle of Guillaume de Nangis, written by a monk at the Abbey of Saint-Denis outside Paris, recorded that in April the rains came down hard — and didn’t stop until August.

Drenched and starved of sunlight, the crops failed across Europe. The price of food doubled and then quadrupled. By May 1316, crop production in England was down by up to 85 percent and there was “most savage, atrocious death”, as a chronicler put it. Hopeless townsfolk walked into the countryside, searching for any bits of food; men wandered across the country to work, only to return and find their wives and children dead from starvation. At one point, on the road near St Albans, no food could be found even for the king. Emaciated bodies could be seen floating face down in flooded fields.

The Great Famine killed anywhere between 5-12% of the European population, although some areas, such as Flanders, suffered far worse death rates, losing up to a quarter of their population to hunger.

July 6, 2022

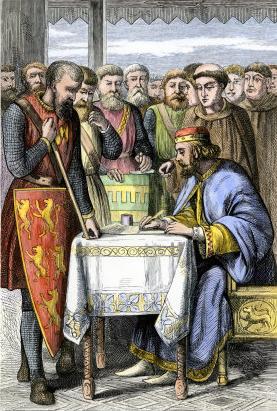

“The Great Charter of the Liberties” was signed on June 15, 1215 at Runnymede

Ed West on the connections between England’s Magna Carta and the American system (at least before the “Imperial Presidency” and the modern administrative state overwhelmed the Republic’s traditional division of powers):

King John signs Magna Carta on June 15, 1215 at Runnymede; coloured wood engraving, 19th century.

Original artist unknown, held by the Granger Collection, New York. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

England does not really go in for national monuments, and when it does they are often eccentric. There is no great shrine to Alfred the Great, for example, the great founder of our nation, but we do have, right in the middle of London, a large marble memorial to the animals that gave their lives in the fight against fascism. And Runnymede, which you could say is the birthplace of English liberty, would be a deserted lay-by were it not for the Americans.

Beside the Thames, some 10 miles outside London’s western suburbs, this place “between Windsor and Staines”, as it is called in the original document, is a rather subdued spot, with the sound of constant traffic close by. Once there you might not know it was such a momentous place were it not for an enclosure with a small Romanesque circus, paid for by the American Association of Lawyers in 1957.

American lawyers are possibly not the most beloved group on earth, but it would be an awful world without them, and for that we must thank the men who on June 15, 1215 forced the king of England to agree to a document, “The Great Charter of the Liberties”.

Although John went back on the agreement almost immediately, and the country fell into civil war, by the end of the century Magna Carta had been written into English law; today, 800 years later, it is considered the most important legal document in history. As the great 18th-century statesman William Pitt the Elder put it, Magna Carta is “the Bible of the English Constitution”.

It was also, perhaps more importantly to the world, a huge influence on the United States. That is why today the doors to America’s Supreme Court feature eight panels showing great moments in legal history, one with an angry-looking King John facing a baron in 1215.

Magna Carta failed as a peace treaty, but after John’s death in 1216 the charter was reissued the following year, an act of desperation by the guardians of the new boy king Henry III. In 1300 his son Edward I reconfirmed the Charter when there was further discontent among the aristocracy; the monarch may have been lying to everyone in doing so, but he at least helped establish the precedent that kings were supposed to pretend to be bound by rules.

From then on Parliament often reaffirmed Magna Carta to the monarch, with 40 such announcements by 1400. Clause 39 heavily influenced the so-called “six statutes” of Edward III, which declared, among other things, that “no man, of whatever estate or condition he may be … could be dispossessed, imprisoned, or executed without due process of law”, the first time that phrase was used.

Magna Carta was last issued in 1423 and then barely referenced in the later 15th or 16th centuries, with the country going through periods of dynastic fighting followed by Tudor despotism and religious conflict. By Elizabeth I’s time, Magna Carta was so little cared about that Shakespeare’s play King John didn’t even mention it.

June 22, 2022

The Day the Viking Age Began

Tasting History with Max Miller

Published 21 Jun 2022For 15% off your first order with Porter Road, click the link https://porterroad.com/MAXMILLER

VIKING BLOD MEAD: https://bit.ly/meadandmore

Support the Channel with PATREON ► https://www.patreon.com/tastinghistory

Merch ► https://crowdmade.com/collections/tas…

Instagram ► https://www.instagram.com/tastinghist…

Twitter ► https://twitter.com/TastingHistory1

Tiktok ► TastingHistory

Reddit ► https://www.reddit.com/r/TastingHistory/

Discord ► https://discord.gg/d7nbEpy

Amazon Wish List ► https://amzn.to/3i0mwGtSend mail to:

Tasting History

22647 Ventura Blvd, Suite 323

Los Angeles, CA 91364LINKS TO SOURCES**

An Early Meal by Daniel Serra & Hanna Tunberg: https://amzn.to/3MOJSNb

Anglo Saxon Chronicle: https://amzn.to/3tBBoCx

The Oxford History of the Vikings by Peter Sawyer: https://amzn.to/3zElwmlRECIPE

1 pound (½ kg) pork meat

Salt for seasoning

2 tablespoons (25g) Lard or another oil for cooking

1 ½ cups (125g) chopped spring onion, or leek

2 teaspoons brown mustard seeds, roughly crushed

1 teaspoon chopped mint

1 pound (½ kg) fresh berries

½ cup (120ml) water

½ cup (120ml) mead1. Season the meat, then heat the lard/oil in a pot on the stove. Sear the meat for 5-7 minutes until well browned. Then remove it and set aside.

2. Add the onion to the pot and cook for 2-3 minutes, then add the water and mead and bring to a simmer. Add the mustard seed and mint and return the pork to the pot. Return to a simmer then cover the pot and place it in an oven at 325°F/160°C for 15-25 minutes or until the pork reaches 145°F. Then remove the pot from the oven and remove the pork to let it rest.

3. Add the berries into the pot with the braising liquid and cook on the stove for 7-10 minutes or until very soft. Mash the berries, then pour everything through a strainer. Return the liquid to the pot and simmer for several minutes or until the sauce reduces down. The sauce will not become too thick without the addition of starch (optional).

4. Slice the pork and serve with the sauce, extra berries, and mint.

**Some of the links and other products that appear on this video are from companies which Tasting History will earn an affiliate commission or referral bonus. Each purchase made from these links will help to support this channel with no additional cost to you. The content in this video is accurate as of the posting date. Some of the offers mentioned may no longer be available.

Subtitles: Jose Mendoza | IG @worldagainstjose

PHOTO

Lindisfarne Priory: Mstanyauk, CC BY-SA 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/…, via Wikimedia Commons

Disneyland: Sean MacEntee via Flickr, CC BY-SA 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/…, via Wikimedia Commons

France Relics: Dennis Jarvis via Flickr, CC BY-SA 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/…, via Wikimedia Commons

Holy Island Sunrise (again): By Chris Combe from York, UK – CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index…

Viking Age Map: By en:User:Bogdangiusca – Earth map by NASA; Data based on w:File:Viking Age.png (now: File:Vikingen tijd.png), which is in turn based on http://home.online.no/~anlun/tipi/vro… and other maps., CC BY-SA 3.0, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/…” rel=”noopener” target=”_blank”>https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index…

Lindisfarne Priory Ruins: Nilfanion, CC BY-SA 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/…, via Wikimedia Commons

Statue of Rollo: By Delusion23 – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index…MUSIC

Battle of the Creek by Alexander Nakarada (www.serpentsoundstudios.com)

Licensed under Creative Commons BY Attribution 4.0 License

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/b…#tastinghistory #viking

June 9, 2022

A brutal microcosm of the English Civil War

At The Critic, Jonathan Healey reviews The Siege of Loyalty House by Jessie Childs:

Late in the summer of 1641, with Charles I deep in dispute with his Parliament, alarming reports reached Westminster of Catholics amassing arms at Basing House in Hampshire. At this point in time, few expected civil war, but plenty feared an imminent Catholic plot. Recent reform to the Church had introduced lavish ceremonies which looked, to many eyes, like the trappings of Rome, and Charles himself was married to a Catholic.

More to the point, England’s Catholics had done it before. Every year, people marked the anniversary of the Gunpowder Treason, which was already stuck in the national consciousness as the quintessential Popish rebellion: an armed coup plotted by dissident aristocrats gathering weapons on their great rural estates and planning subterfuge at the highest levels.

Yet civil war came, and when it did it would be nothing like the “Popish Plots” of Protestant imagining. It would be fought over constitutional as much as religious divides. And, rather than a rebellion, it would be an armed struggle between two competing fiscal-military organisations — effectively between two competing states.

The English countryside became militarised. Now, it was not just a landscape. It was territory. The great houses were no longer places for covert plotting; now they were centres of command and control. And few were more important than Basing House.

Hampshire today is a pleasant place: gentle and verdant with rolling chalk hills, shaded woodlands, and quiet valleys. But in the 1640s it became contested and dangerous: a dark, malevolent land of violence and death. People looked upon one another with suspicion, and riders were ambushed and killed as they travelled at night. Parish churches were stormed, towns starved and bombarded. Armies of musketeers, pikemen, and cavalry traversed the folding lanes of the county looking to bring bloodshed and plunder.

[…]

A crucial theme is encapsulated in the book’s denouement. The deputy sent to pacify Hampshire for the New Model was Oliver Cromwell. He had been in the thick of the fighting from the start, and before then was an earnest — if obscure and scruffily-attired — Member of Parliament. But Cromwell really rose to prominence in 1644 and 1645, on the back of his military abilities. He represented a new approach to the war: the pursuit of total victory even at the cost of sharp bloodshed.

It was Cromwell’s direct — even brutal — efficiency that brought the siege of Basing House to its end. The walls fell and many of the garrison were killed. Slaughtered, too, were a number of Catholic priests in a moment of violence that was representative of the way the war was heading. Cold-blooded murder of female camp followers had been perpetrated by royalists in Cornwall and by parliamentarians after Naseby. King Charles had allowed a bloody storm of Leicester which had cost many civilian lives, and Cromwell would go on to oversee the horrors of Drogheda and Wexford in Ireland. The chivalry of Waller and Hopton would come to seem a long way in the past.

May 20, 2022

The Crusades: Part 7 – The Third Crusade

seangabb

Published 5 Mar 2021The Crusades are the defining event of the Middle Ages. They brought the very different civilisations of Western Europe, Byzantium and Islam into an extended period of both conflict and peaceful co-existence. Between January and March 2021, Sean Gabb explored this long encounter with his students. Here is one of his lectures. All student contributions have been removed.

(more…)

May 15, 2022

The young man who might have been King Henry IX of England

In the latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes considers what might have been had the eldest son of King James I and VI lived to take the thrones of England and Scotland:

Portrait of Prince Henry Frederick (1594-1612), Prince of Wales by Isaac Oliver

National Trust, Dunster Castle; http://www.artuk.org/artworks/prince-henry-frederick-15941612-prince-of-wales-99804 via Wikimedia Commons.

Henry Frederick, Prince of Wales, was the eldest son and heir of James I of England. He would presumably have become Henry IX had he managed to outlive his father. But he died in 1612 aged just 18. The kingdom instead ended up with his younger brother Charles I and civil war. I’m not sure how far Prince Henry was influenced, but it seems that many of the major innovators of the period were purposefully cultivating him as a kind of inventor-scientist king.

It reminds me of a very similar and successful scheme, which I noticed when researching my first book on the history of the Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce. This was the scheme to cultivate George III — famed for his madness and losing the Thirteen Colonies, but also for his collection of scientific instruments and interest in agricultural innovation. Those interests were no accident: his upbringing had included lessons in botany from the inventor Stephen Hales, in art and architecture from William Chambers, and in mathematics from George Lewis Scott. These were not just experts, but active innovator-organisers. Hales was a key founder of the Society of Arts; Chambers helped organise the artists who split off from it to form the Royal Academy of Arts; and Scott was involved in updating Ephraim Chambers’s Cyclopaedia, or Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences — an early encyclopaedia focused on technical knowledge. And their efforts bore fruit. Unlike his predecessor and grandfather George II — whose interests mainly fell under the headings of Handel, Hanover, hunting, and heavy women — George III became an active patron of science, invention, and the arts.

Given how successfully the inventors cultivated George III, it makes me wonder how things might have looked had Prince Henry lived to be king. His younger brother Charles I had an education heavily geared towards languages, theology, and overcoming various health issues through sports. But Henry — naturally athletic and charismatic — had an upbringing tightly controlled by Sir Thomas Chaloner, who had a major financial stake in innovation.

Chaloner housed and supported his alchemist cousin (also, confusingly, called Thomas Chaloner). This cousin had published an early treatise on the medical applications of saltpetre, or nitre (what we now call potassium nitrate), and had tried to produce alum on the isle of Lambay, off the coast of Ireland. Alum was a valuable substance used to fix cloth dyes, which had hitherto been monopolised by the Pope, who owned Europe’s only alum mine. Opening a competing, English-controlled, Protestant supply of alum was not just about starting a new industry. It was a matter of Europe-wide religious and strategic urgency.

[…]

Henry’s circle also included the Dutch polymath Cornelis Drebbel, who would become famous all over Europe for travelling in a submarine under the Thames, for his improvements to microscopes, and for inventing a perpetual motion machine (which isn’t as silly as it sounds — it was effectively a kind of barometer, exploiting changes in temperature and air pressure to move).

And that’s just the tip of the iceberg. The more I look into the circle of inventors around Prince Henry, the more familiar names crop up. There even seems to be some connection to Simon Sturtevant, one of the original patentees of a method to make iron by using coal instead of wood — Chaloner was seemingly responsible for evaluating Sturtevant’s inventiveness, to see if he merited a patent. I found it very striking that when Sturtevant’s iron-making business was about to get going, Prince Henry was to have a share.

Given such innovative company, we can only imagine what kind of a king Prince Henry might have been. If George III grew up to be “Farmer George”, might a Henry IX have become associated with navigation or hydraulic engines? We’ll never know. But even during his brief lifetime, there was plenty of patronage to be had for inventors at the court of their would-be Inventor-King.

May 3, 2022

England’s class system, as documented by George Orwell and Theodore Dalrymple

I occasionally run into articles online that are clearly written to interest someone like me, and this one in Quillette by Laurie Wastell had my full attention from the title onward:

Ever since Marx, the concept of class has been foundational to sociology — as well as to almost everything else. This would not have surprised the German economist, for class, as he saw it, determines all: one’s motivations, one’s social position, even one’s consciousness. Britain, where Marx’s Capital was written, has long been known for its intricate class system, and as such is the source of much writing on the subject. Two of the most acerbic English social critics of the past century, George Orwell and Theodore Dalrymple, take class as a central subject. Drawing on firsthand experience (Orwell as a journalist, Dalrymple as a prison doctor and psychiatrist), both document in detail the suffering and privations of the class below them. Both also contend that a central cause of this poverty is the indifference of the middle and upper classes, a conclusion Marx would surely have agreed with. Yet, despite this, their work stands in flat contradiction to Marx’s central dogma that the material conditions of a society determine everything about it, including class. In their literary journalism, the authors’ social commentaries and insights into the human condition far surpass Marx’s “scientific” analysis.

[…]

That class is a function more of outlook than income was clear to Orwell, as he explains in his 1937 book The Road to Wigan Pier, which depicts both the privations of working-class life and the British class system as a whole. Orwell describes how the “lower-upper-middle-class” (Orwell’s own), generally professionals in the “Army, Navy, Church, Medicine [or] Law”, understood and aspired to all the many customs of the upper classes (hunting, servants, how to order dinner correctly) despite never being able to afford them. Thus, “To belong to this class when you were [only] at the £400 a year level was a queer business, for it meant that your gentility was almost purely theoretical.” This same dynamic applies today (though the bourgeois values aspired to now are quite different): a poor librarian is far less likely than a wealthy plumber to have voted for causes like Brexit or Trump, which are both populist and, thus, lower-class.

Themselves men of letters, both Orwell and Dalrymple understand that this class distinction is frequently signalled through language. “As for the technical jargon of the Communists,” writes Orwell, “it is as far removed from the common speech as the language of a mathematical textbook.” Such contorted academic prose means little to the ordinary worker, for whom, Orwell argues, Socialism simply means “justice and common decency”. Indeed, Orwell laments that “the worst advertisement for Socialism is its adherents” because of their distance from everyday concerns and inability to speak plainly. Summarising the problem, he quips: “The ordinary man may not flinch from a dictatorship of the proletariat, if you offer it tactfully; offer him a dictatorship of the prigs, and he gets ready to fight”.

A lifelong socialist, Orwell was repeatedly frustrated by the symptoms of this intellectual snobbery — why do the revolutionaries have such disdain for the ordinary punter? Dalrymple, meanwhile, in his essay “How — and How Not — to Love Mankind”, takes aim at its roots. Here, Dalrymple compares the life and work of Marx to his now lesser-known contemporary, Russian novelist and playwright Ivan Turgenev. Though their lives closely resembled one another’s, Dalrymple argues, “They nevertheless came to view human life and suffering in very different, indeed irreconcilable, ways — through different ends of the telescope, as it were. Turgenev saw human beings as individuals always endowed with consciousness, character, feelings, and moral strengths and weaknesses. Marx saw them always as snowflakes in an avalanche, as instances of general forces, as not yet fully human because utterly conditioned by their circumstances.”

[…]

Both writers criticise intellectuals’ pretentious jargon, but it is worth pausing over how each relates his own social position to their subject matter. In a telling passage of Wigan Pier, Orwell describes the working man who has made it into the middle class, perhaps as a Labour MP or trade union official, as “one of the most desolating spectacles the world contains. He has been picked out to fight for his mates, and all it means to him is a soft job and a chance of ‘bettering’ himself. Not merely while but by fighting the bourgeoisie he becomes bourgeois himself.” The scare quotes reflect Orwell’s mixed feelings about social class: does Orwell not believe that a middle-class career — such as his own — is an improvement over the harsh, backbreaking labour of the miners he so vividly documents? He has hit on a deep dilemma, born of a compassionate humanism that points in contradictory directions.

Ostensibly, Orwell chronicles poverty in order to change it, to shock the comfortable hearts of his readers into action. Yet, at the same time, (romanticising the poor against his own advice), he presents the dirt as liberating: squalor and poverty are in some sense more authentic, more real than bourgeois comforts. Thus, as literary critic John Carey argues, Orwell’s “phobia about lower-class dirt collides head-on with his determination to invest dirt with political value, as the price of liberty.”