Here it is instructive to look at the statistics for house burglary in England and Wales. 750-800,000 such burglaries were known to the police in 2006; the police found the burglars in about 66,000 cases. (The figures for the number of burglaries are underestimated, while those for the numbers of burglaries solved are overestimated, both for technical reasons not necessary to go into, and that we can for the sake of argument ignore.) In that year, just over 6000 burglars received prison sentences. In other words, even if caught, a burglar in England and Wales is not likely to go to prison; but he is even less likely to be caught in the first place. In this sense, then, criminals do indeed have nothing to lose, and possibly much to gain by criminality.

Theodore Dalrymple, “It’s a riot”, New English Review, 2012-04.

February 1, 2018

QotD: In Britain, crime does pay

January 30, 2018

Fitness tracker heat map shows dangerous activity near wrecked WW2 ammunition ship

The SS Richard Montgomery was a WW2 Liberty ship that ran aground near Sheerness in August 1944 carrying a cargo of bombs and other explosives. Part of the cargo was removed before the ship broke up and sank just offshore. There’s still quite a lot of TNT onboard the wreck, and it’s recently come to light that someone has been visiting the wreck, thanks to fitness tracker data:

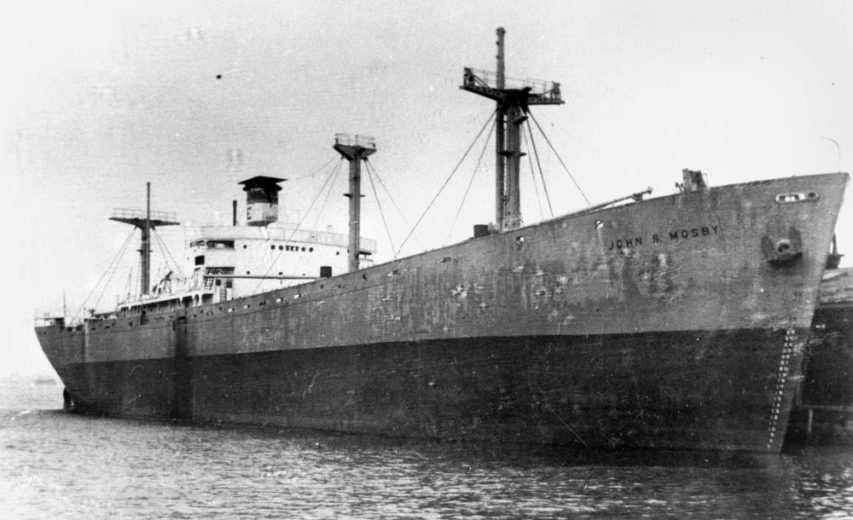

The SS John S. Mosby, a Liberty ship similar to the SS Richard Montgomery

Photo from the John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland, via Wikimedia.

The information came to light after social media users realised that the latest version of Strava’s heat map, which shows the aggregated routes of all of its users, could be used to figure out where Western military bases in the Middle East are. Fitness-conscious soldiers, running around the bases’ perimeters, built up visible traces on the heat map over time.

However, of much more concern is the revelation that people have been poking around the wreck of the SS Richard Montgomery, a Second World War cargo ship that was carrying thousands of tonnes of explosive munitions from America to the UK. The ship grounded in the Thames Estuary, in England, in August 1944, barely two miles north of Sheerness.

Extract from Admiralty chart of Sheerness (Crown copyright):

The multicoloured box is the location of the SS Richard Montgomery wreckAlthough wartime salvage parties managed to scavenge a large amount of ordnance from the grounded Liberty ship, her hull split in two and sank, taking around 1,400 tonnes of explosives down with her, before the job could be completed. Officials decided to leave the wreck in place.

According to a 1995 survey report [PDF] on the wreck: “The bombs thought to be on board are of two types. The bulk are standard, un-fused TNT bombs. In addition, some 800 fused cluster bombs are believed to remain. These bombs were loaded with TNT. They could be transported fused because the design included a propeller mechanism at the front which only screwed the fuse into position as the bombs fell from an aircraft. All the bombs could therefore be handled – with care – when the accident occurred.”

[…]

The 1995 report noted that TNT “does not react with water and will not explode if it is damp”, before adding that the brass-cased cluster bombs’ lead-based fuses “will combine with brass to produce a highly unstable copper compound which could explode with the slightest disturbance”. Although the compound “if formed, will wash away in a few weeks”, it was not made clear in the report how often the compound forms and creates the dangerous hair-trigger condition. Experts believe that the best way of keeping the wreck safe is not to disturb it, which led to a 500-metre exclusion zone being imposed around it.

I thought the ship’s name sounded familiar … I posted a video about the dangers of this wreck back in 2013. Last month, I posted a video about the Liberty ship program.

December 2, 2017

Breaking news from 55 BC

Despite the written records left by Julius Caesar, Cicero, and Tacitus, until now there had apparently been no physical evidence of Caesar’s invasion of Britain:

… a chance excavation carried out ahead of a road building project in Kent has uncovered what is thought to be the first solid proof for the invasion.

Archaeologists from the University of Leicester and Kent County Council have found a defensive ditch and javelin spear at Ebbsfleet, a hamlet on the Isle of Thanet.

The shape of the ditch at Ebbsfleet, is similar to Roman defences at Alésia in France, where a decisive battle in the Gallic War took place in 52 BC.

Experts also discovered that nearby Pegwell Bay is one of the only bays in the vicinity which could have provided harbour for such a huge fleet of ships. And its topography echoes Caesar’s own observations of the landing site.

Dr Andrew Fitzpatrick, Research Associate from the University of Leicester’s School of Archaeology and Ancient History said: “Caesar describes how the ships were left at anchor at an even and open shore and how they were damaged by a great storm. This description is consistent with Pegwell Bay, which today is the largest bay on the east Kent coast and is open and flat.

“The bay is big enough for the whole Roman army to have landed in the single day that Caesar describes. The 800 ships, even if they landed in waves, would still have needed a landing front 1-2 km wide.

“Caesar also describes how the Britons had assembled to oppose the landing but, taken aback by the size of the fleet, they concealed themselves on the higher ground. This is consistent with the higher ground of the Isle of Thanet around Ramsgate.”

Thanet has never been considered as a possible landing site before because it was separated from the mainland until the Middle Ages by the Wanstum Channel. Most historians had speculated that the landing happened at Deal, which lies to the south of Pegwell Bay.

November 14, 2017

Why the Vikings Disappeared

KnowledgeHub

Published on 17 Feb 2017The Vikings were infamous in the Middle Ages for their raids against the coasts of Northern Europe. Their age however was quite brief in the span of time, only 300 years. What caused the end of the Vikings?

November 5, 2017

England: A Beginner’s Guide

exurb1a

Published on 4 Jul 2016I notice that it’s also independence day. How fitting.

You just wait until we throw all your tea in the fucking ocean.The music is Pomp and Circumstance No.1 by Elgar ► https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=moL4MkJ-aLk

October 13, 2017

August 7, 2017

How to Swear Like a Brit – Anglophenia Ep 29

Published on 20 May 2015

Swearing is a fun stress reliever, and the British do it so well. Anglophenia’s Kate Arnell provides a master class in swearing like a Brit.

August 6, 2017

Recap Of Our Trip To England I THE GREAT WAR Special

Published on 5 Aug 2017

Stow Maries Great War Aerodrome: http://www.stowmaries.org.uk/

The Tank Museum, Bovington: http://www.tankmuseum.org/

The Prince of Wales, Restaurant: http://www.prince-stowmaries.net/

July 6, 2017

English place name pronunciation for non-English folks

I was born in England, but having been in Canada for most of my life, I don’t have an infallible key to remembering how to pronounce many English town and region names. Kim du Toit is on an extended visit to Blighty, so he does his best here to clue in all us furriners about English place names:

The town of Cirencester is pronounced “Siren-sister”, but the town of Bicester is not Bye-sister, but “Bister”, like mister. Similarly, Worcester is pronounced “Wusster” (like wussy), which makes the almost unpronounceable Worcestershire (the county) quite simple: “Wusster-shirr” (and not Wor-sester-shyre, as most Americans mispronounce it).

Now pay careful attention. A “shire” (pronounced “shyre”) is a name for county*, but when it comes at the end of a word, e.g. Lincolnshire, it’s pronounced “Linconn-shirr”. The shire is named after the county seat, e.g. the aforementioned Worcester (“Wusster”) becomes Worcestershire (“Wuss-ter-shirr”) and Leicester (“Less-ter”) becomes Leicestershire (“Less-ter-shirr”). Unless it’s the town of Chester, where the county is named Cheshire (“Chesh-shirr”) and not Chester-shirr. Also Lancaster becomes Lancashire (“Lanca-shirr”), not Lancaster-shirr, and Wilton begat Wiltshire (“Wilt-shirr”). Wilton is not the county seat; Salisbury is. Got all that?

*Actually, “shire” is the term for a noble estate, e.g. the Duke of Bedford’s estate was called Bedfordshire, which later became a county; ditto Buckingham(-shire) and so on, except in southern England, where the Old Saxon term held sway, and the estate of the Earl of Essex became “Essex” and not Essex-shire, which would have been confusing, not to say unpronounceable. Ditto Sussex, Middlesex and Wessex. Also, the “-sexes” were once kingdoms and not estates. And in the northeast of England are places named East Anglia (after the Angles settled there) and Northumbria (ditto), which isn’t a county but an area (once a kingdom), now encompassing as it does Yorkshire and the Scottish county Lothian — which I’m not going to explain further because I’m starting to bore myself.

And all rules of pronunciation go out the window when it comes to Northumbrian accents like Geordie (in Newcastle-On-Tyne) anyway, because the Geordies are incomprehensible even to the Scots, which just goes to show you.

Now here’s where it gets really confusing.

Update: I managed to get seven of the nine (but one was a guess … a friend on the outskirts of Pittsburgh had tipped me off): Atlas Obscura on unusual demonyms. The ones I didn’t get were Leeds and Wolverhampton.

Here’s a very fun game to play: Take a list of cities with unusual demonyms — that’s the category of words describing either a person from a certain place, or a property of that place, like New Yorker or Italian — and ask people to guess what the demonym is. Here are some favorites I came up with, with the help of historical linguist Lauren Fonteyn, a lecturer at the University of Manchester. It’s tilted a bit in favor of the U.K. for two reasons. First is that Fonteyn lives and works there, and second is that the U.K. has some excellently weird ones. The answer key is at the bottom.

- Glasgow, Scotland

- Newcastle, England

- Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

- Liverpool, England

- Leeds, England

- Wolverhampton, England

- Madagascar

- Halifax, Canada

- Barbados

Demonyms are personal and vital to our conceptions of ourselves. Few things are more important to our identities than where we’re from. This explains why people invariably feel the need to correct anyone who gets their demonym wrong. “It’s understudied but it’s kind of important,” says Fonteyn, who is originally from Belgium. “I moved to Manchester and had no idea what the demonym was. And if you do it wrong, people will get very, very mad at you.”

The demonym for people from or properties of Manchester is “Mancunian,” which dates back to the Latin word for the area, “Mancunium.” It is, like the other fun demonyms we’re about to get into, irregular, which means it does not follow the accepted norms of how we modify place names to come up with demonyms. In other words, someone has to tell you that the correct word is “Mancunian” and not “Manchesterian.”

July 4, 2017

The linguistic weirdness of English

Native English speakers tend to have difficulties acquiring their first foreign language because their mother tongue has failed to equip them with what other languages consider quite basic tools, like gendered nouns, relatively sensible quasi-phonetic spelling, and relatively stable patterns for conjugating verbs. In a post from a few years back, John McWhorter points out a few of the weird spots of English and where they came from in the first place:

English speakers know that their language is odd. So do people saddled with learning it non-natively. The oddity that we all perceive most readily is its spelling, which is indeed a nightmare. In countries where English isn’t spoken, there is no such thing as a ‘spelling bee’ competition. For a normal language, spelling at least pretends a basic correspondence to the way people pronounce the words. But English is not normal.

Spelling is a matter of writing, of course, whereas language is fundamentally about speaking. Speaking came long before writing, we speak much more, and all but a couple of hundred of the world’s thousands of languages are rarely or never written. Yet even in its spoken form, English is weird. It’s weird in ways that are easy to miss, especially since Anglophones in the United States and Britain are not exactly rabid to learn other languages. But our monolingual tendency leaves us like the proverbial fish not knowing that it is wet. Our language feels ‘normal’ only until you get a sense of what normal really is.

[…]

English started out as, essentially, a kind of German. Old English is so unlike the modern version that it feels like a stretch to think of them as the same language at all. Hwæt, we gardena in geardagum þeodcyninga þrym gefrunon – does that really mean ‘So, we Spear-Danes have heard of the tribe-kings’ glory in days of yore’? Icelanders can still read similar stories written in the Old Norse ancestor of their language 1,000 years ago, and yet, to the untrained eye, Beowulf might as well be in Turkish.

The first thing that got us from there to here was the fact that, when the Angles, Saxons and Jutes (and also Frisians) brought their language to England, the island was already inhabited by people who spoke very different tongues. Their languages were Celtic ones, today represented by Welsh, Irish and Breton across the Channel in France. The Celts were subjugated but survived, and since there were only about 250,000 Germanic invaders – roughly the population of a modest burg such as Jersey City – very quickly most of the people speaking Old English were Celts.

Crucially, their languages were quite unlike English. For one thing, the verb came first (came first the verb). But also, they had an odd construction with the verb do: they used it to form a question, to make a sentence negative, and even just as a kind of seasoning before any verb. Do you walk? I do not walk. I do walk. That looks familiar now because the Celts started doing it in their rendition of English. But before that, such sentences would have seemed bizarre to an English speaker – as they would today in just about any language other than our own and the surviving Celtic ones. Notice how even to dwell upon this queer usage of do is to realise something odd in oneself, like being made aware that there is always a tongue in your mouth.

At this date there is no documented language on earth beyond Celtic and English that uses do in just this way. Thus English’s weirdness began with its transformation in the mouths of people more at home with vastly different tongues. We’re still talking like them, and in ways we’d never think of. When saying ‘eeny, meeny, miny, moe’, have you ever felt like you were kind of counting? Well, you are – in Celtic numbers, chewed up over time but recognisably descended from the ones rural Britishers used when counting animals and playing games. ‘Hickory, dickory, dock’ – what in the world do those words mean? Well, here’s a clue: hovera, dovera, dick were eight, nine and ten in that same Celtic counting list.

June 24, 2017

How To Insult Like the British – Anglophenia Ep 12

Published on 8 Sep 2014

If you ever get into an argument with a British person, you’ll wish you’d have watched this video. Siobhan Thompson gives you the tools to sling insults like a Brit.

Here are a few other insults via the Anglophenia blog: http://www.bbcamerica.com/anglophenia/2012/08/the-brit-list-10-stinging-british-insults/

June 23, 2017

British and Irish Iron Age hill forts and settlements mapped in new online atlas

In the Guardian, Steven Morris talks about a new online resource for archaeological information on over 4,000 Iron Age sites:

Some soar out of the landscape and have impressed tourists and inspired historians and artists for centuries, while others are tiny gems, tucked away on mountain or moor and are rarely visited.

For the first time, a detailed online atlas has drawn together the locations and particulars of the UK and Ireland’s hill forts and come to the conclusion that there are more than 4,000 of them, mostly dating from the iron age.

The project has been long and not without challenges. Scores of researchers – experts and volunteer hill fort hunters – have spent five years pinpointing the sites and collating information on them.

[…]

Sites such as Maiden Castle, which stretches for 900 metres along a saddle-backed hilltop in Dorset, are obvious. But some that have made the cut are little more than a couple of roundhouses with a ditch and bank. Certain hill forts in Northumbria are tiny and probably would not have got into the atlas if they were in Wessex, where the sites tend to be grander.

Many hill forts will be familiar, such as the one on Little Solsbury Hill, which overlooks Bath. But there are others, such as a chain of forts in the Clwydian Range in north-east Wales, that are not so well known. Many are in lovely, remote locations but there are also urban ones surrounded by roads and housing.

The online atlas and database will be accessible on smartphones and tablets and can be used while visiting a hill fort.

H/T to Jessica Brisbane for the link.

June 11, 2017

Nostalgia for a lost England

David Warren got all weepy about bygone times in England:

I lived in England — London, to be more frank, but with much wandering about — through the middle ’seventies and for a shorter spell in the early ’eighties. By the late ’nineties I visited a place that had been in many ways transformed, and clearly for the worse, by the Thatcher Revolution. Tinsel wealth had spread everywhere, trickling down into every crevice. Tony Blair surfed the glitter, and people with the most discouraging lower-class accents were wearing loud, expensive, off-the-rack garments, and carrying laptops and briefcases. No hats. It was a land in which one could no longer find beans-egg-sausage-and-toast for thirty-five new pence, nor enter the museums for free.

I missed that old Labour England, with the coalfield strikes, and the economy in free fall; with everything so broken, and all the empty houses in which one could squat; the quiet of post-industrial inanition, and the working classes all kept in their place by the unions. I loved the physical decay, the leisurely way people went about their charmingly miserable lives. Cricket still played in cricket whites; the plaster coming off the walls in pubs. It was all so poetical. And yes, Mrs Thatcher had ruined all that. For a blissful moment I was thinking, Corbyn could bring it back.

Actually, he would bring something more like Venezuela, but like the youff of England, one can still dream.

I visited England as an adult in mid-Winter 1979, the “Winter of Discontent“, and it was a fantastically appropriate epithet for a chilly, damp, and miserable time-and-place. When we landed at Heathrow, there was some kind of disruption with both the bus service and the underground (“subway” to us North Americans), so getting into London required taking a cab. The cabbie “kindly” took us around a bunch of touristy sites (and probably ran up the meter a fair bit) before dropping us off at King’s Cross station. When we bought our tickets for the train north to Darlington, we were warned that the catering staff were not working that day (no idea whether there was a formal strike or just a wildcat walkout), so there were no meals available on the train. The restaurant at the station was closed — that might just have been the time we were there, as British restaurant opening and closing hours were quite restricted at the best of times.

On the train, we were at least able to get a cup of tea and a stale bun. The journey took quite some time — once again, that might have been normal, but what was supposed to be a ~3 hour journey probably took closer to 5 hours (maintenance, signalling issues, strike-related delays, and for all I know the “wrong kind of snow” were all possible contributors). By then, we’d missed our connecting train to Middlesbrough, but they ran fairly frequently so we weren’t held up too long. We finally reached my Grandmother’s house, only to discover that we might be hit by blackouts as the power station workers were threatening to go off the job. It was a dismal and yet appropriate welcome back to the place I’d left as a child in 1967 … it was tough to recognize the places I thought I remembered, as childhood memories tend to emphasize the (fleeting) warmth and sunshine and ignore the much more traditional wet and windy British weather.

I left Toronto wearing normal winter clothing, which was well adapted to our Canadian winters, but not at all appropriate to the bitter, wet cold of Northeast England at the best of times and this was the worst winter since 1963. My teeth started to chatter as we left the terminal at Heathrow and didn’t stop chattering until the door closed on the aircraft for our return two weeks later (in the middle of a huge winter snowstorm that had us on one of the few aircraft that arrived or departed that day).

My brief two weeks’ experience of England’s Winter of Discontent didn’t build up any particularly rich sense of nostalgia, let me tell you…

April 29, 2017

If Walls Could Talk The History of the Home Episode 4: The Kitchen

Published on 2 Feb 2017

April 16, 2017

If Walls Could Talk The History of the Home Episode 3 The Bedroom

Published on 1 Feb 2017