Matthew Mitchell (MM): Tell us a little bit about the job of a planner. What were your responsibilities? And how did you go about doing them?

Gia Jandieri (GM): Our department inside of Gossnab [the State Supply Committee for the Central Planning Authority] was responsible for monitoring the execution of agreements for production of goods and government orders. My task was to verify that the plans had been executed correctly, to find failures and problems, and to report to the higher authorities.

This included reading lots of reports and visiting the factories and their warehouses for auditing.

The Soviet economy had been in a troublesome condition since the 1970s. We (at the Gossnab) had plenty of information about failures, but it wasn’t useful. We knew that the quality of produced goods was very low, that any household good that was of usable quality was in deficit, and that the shortages encouraged people to buy on the black market through bribes.

In reality, a bribe was a substitute for a market-determined price; people were interested in paying more than the official price for the goods they valued, and the bribe was a way for them to indicate that they valued it more than others.

The process of planning was long. The government had to study demand, find resources and production capacities, create long-run production and supply plans, compare these to political priorities, and get approval for general plans at the Communist Party meetings. Then the general plans needed to be converted to practical production and supply plans, with figures about resources, finances, material and labour, particular producers, particular suppliers, transportation capacities, etc. After this, we began the process of connecting factories and suppliers to one another, organizing transportation, arranging warehousing, and lining up retail shops.

The final stage of the planning process was to send the participating parties their own particular plans and supply contracts. These were obligatory government orders. Those who refused to follow them or failed to fulfill them properly were punished. The production factories had no right or resources to produce any other goods or services than those described in the supply contracts and production plans they received from the authorities. Funny enough, though, government officials could demand that they produce more goods than what was indicated in the plans.

Matthew Mitchell, “Central planning from the inside—an interview with a Soviet-era economist”, Fraser Institute, 2024-05-25.

August 26, 2024

QotD: The job of a Soviet economic planner

August 9, 2024

QotD: Celebrity fund-raising for foreign aid

Unlike private capital, foreign “aid” enters a country not because conditions there favor economic growth but because that country is poor — because that country lacks institutions and policies necessary for growth. And the more miserable its citizens’ lives, the more foreign “aid” its government receives.

Can you imagine a more perverse incentive? The poorer and more wretched are a nation’s people, the more likely celebrities such as Bono will convince Westerners and their governments to take pity on that country and to send large sums of money to its government. And because that country’s citizens are poor largely because their government is corrupt and tyrannical, the money paid in “aid” to that government will do nothing to help that country develop economically.

The cycle truly is vicious. Aid money naively paid by Westerners to alleviate Third-World poverty is stolen or misspent by the thugs who control the governments there. Nothing is done to foster the rule of law and private property rights that alone are the foundation for widespread prosperity. The people remain mired in ghastly poverty, their awful plight further attracting the attention and sympathy of Western celebrities, who use their star attraction and media savvy to shame politicians in the developed world into doling out yet more money to the thugs wielding power in the (pathetically misnamed) “developing world”.

If I could figure out a way to measure the long-term consequences of this new round of debt relief — a way that is so clear and objective that even the most biased party could not quibble with it — I would offer to bet a substantial sum of money that years from now this debt relief will be found to have done absolutely no good for the average citizens of the developing world.

It’s a bet I would surely — and sadly — win.

Don Boudreaux, “Faulty Band-Aid”, Pittsburgh Tribune-Review, 2005-06-18.

July 22, 2024

QotD: Post-apartheid South Africa

There were two things that finally caused the dam to break and muted criticism of the South African regime to start appearing in the international press: the first was the situation in Zimbabwe. Like South Africa, Zimbabwe had recently ended decades of white minority rule, but in Zimbabwe things went way more wrong, way more quickly. Robert Mugabe, the incumbent president of Zimbabwe, was running in a contested election, and decided to ensure his victory with a campaign of mass murder and torture which in turn triggered a famine and a refugee crisis.

All of this brought tons of international condemnation onto the Zimbabwean regime, and a lot of countries looking for ways to pressure it to stop the atrocities. The glaring exception was Mbeki’s South Africa, which staunchly defended Zimbabwe for years as the killing and the starvation just kept ratcheting up. It’s unclear why they did this, beyond the ANC and ZANU-PF (the Zimbabwean ruling party) having a certain ideological and familial kinship, both being post-colonialist revolutionary parties that had overthrown white minority rule. But whatever the reason, this was the straw that finally caused Western politicians and celebrities to wake up a little bit and realize that South Africa was now ruled by thugs.

The second, even more catastrophic event that caused the South African government to lose the sheen of respectability was the AIDS epidemic and their response to it. The story of how Mbeki buried his head in the sand, embraced quack theories on the causes of AIDS, and condemned hundreds of thousands of people to avoidable deaths is well known at this point, but Johnson’s book is full of grimly hysterical details that turn the whole story into the darkest comedy you’ve ever seen.

For example: I had no idea that Mbeki was so ahead of his time in outsourcing his opinions to schizopoasters on the internet. According to his confidantes, at the height of the crisis the president was frequently staying up all night interacting pseudonymously with other cranks on conspiracy-minded forums (an important cautionary tale for all those … umm … friends of mine who enjoy dabbling in a conspiracy forum or two). These views were then laundered through a succession of bumbling and imbecilic health ministers such as Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma or Mantombazana Tshabalala-Msimang who gave surreal press conferences extolling the healing powers of “Africanist” remedies such as potions made from garlic, beetroot, and potato.

Actually, the potions were a step up in some respects, the original recommendation from the South African government was that AIDS patients should consume “Virodene”, a toxic industrial solvent marketed by a husband-wife con-artist duo named Olga and Siegfried Visser. Later documents came to light revealing large and inexplicable money transfers between the Vissers and Tshabalala-Msiming. The Vissers then established a secret lab in Tanzania where they experimented on unsuspecting human subjects, engaged in bizarre sexual antics, and performed cryonics experiments on corpses. Despite this busy schedule, they also produced a constant stream of confidential memos on AIDS policy that were avidly consumed by Mbeki.

The horror of it all is that by this point there were very good drugs that could massively cut the risk of mother-child HIV transmission and somewhat reduced the odds of contracting the virus after a traumatic sexual encounter. There were a lot of traumatic sexual encounters. A contemporaneous survey found that around 60 percent of South Africans believed that forcing sex on somebody was not necessarily violence, and a common “Africanist” belief was that sex with a virgin could cure AIDS, all of which led to extreme levels of child rape. The government then did everything in its power to prevent the victims of these rapes from accessing drugs that could stave off a deadly disease. At first the excuse was that they were too expensive, then when the drug companies called that bluff and offered the drugs for free, it became that they caused “mutations”.

John Psmith, “REVIEW: South Africa’s Brave New World, by R.W. Johnson”, Mr. and Mrs. Psmith’s Bookshelf, 2023-03-20.

July 16, 2024

QotD: Corruption and crony capitalism

When leftists look at the private sector, they see tips of icebergs – for every businessperson caught gouging the consumer, they insist there are a thousand under the surface waiting to trap the unwary. Whereas a libertarian like myself sees the mirror image – the odd bad civil servant caught is not a rotten apple as they claim, but the tip of another large iceberg.

Surely we have seen enough to know that large organisations like the government and their crony capitalists in the corporate sector are deeply resistant to independent investigations, whistleblowers and all other genuine threats to their status?

Whereas those that battle away in the competitive private sector don’t even get the chance to be that corrupt – they either treat their customers and employees well, or they crumble into dust like the costumed retards in the entertainment industry are doing so reliably these days, those beloved of progressive dunces the world over.

There are few cover-ups in the world of dogwalking and fishmongering – these people do a good job or they get told to piss off by their customers. But in the public sector and the corporate world that depend upon it …?

When we catch a corrupt civil servant or corporate lackey, we are seeing the Tip of An Iceberg. But when we catch a corrupt landscape gardener or carpenter, we are finding a Rotten Apple.

My claim is that terrible government officials and corrupt crony capitalists are the both the tips of icebergs, so the cries from Left and Right about rotten applies need to go away. Those that work in the public sector or depend upon their relationship with it, are routinely terrible and usually without consequence.

Alex Noble, “Corruption In The Coercive And Voluntary Sectors: Rotten Apples? Or The Tips of Icebergs?”, Continental Telegraph, 2019-12-02.

June 13, 2024

June 10, 2024

South Africa’s “Rainbow Nation” falters

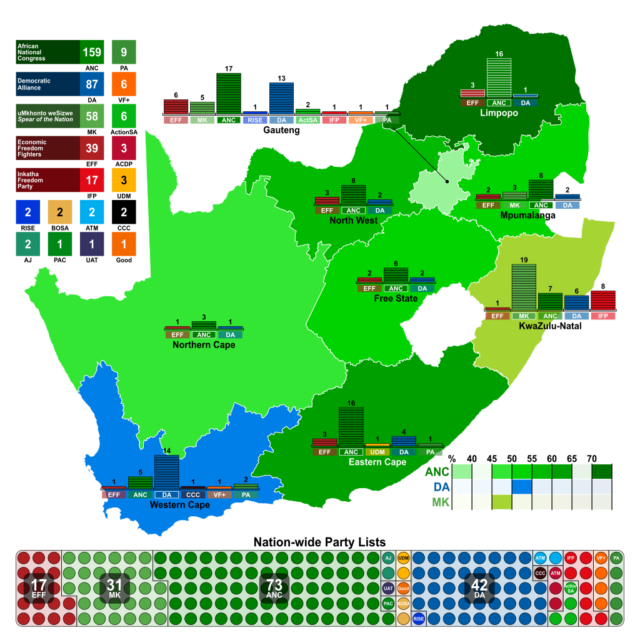

Niccolo Soldo’s weekly roundup included a lengthy section on the recent election results in South Africa and what they might mean for the nation’s short- and medium-term stability:

Being a teen, the issue of South African Apartheid didn’t really fit all that well within the overarching Cold War paradigm. Unlike most other global issues, this one didn’t break down cleanly between the “freedom-loving West” and the “dictatorial, oppressive communist bloc”, as the push to dismantle the regime came from western liberals who were in agreement with the reds.

This slight bit of complexity did not faze most people, as Apartheid was seen as a relic of an older world, one to be consigned to the proverbial dustbin of history. It’s elimination did fit well enough into the Post-Berlin Wall world, one in which freedom and democracy were to reign supreme. This was more than enough reason for almost all people to cheer the release of Nelson Mandela and applaud South Africa’s embrace of western liberal democracy.

In the early 1990s, men once again dared to flirt with utopian ideas, and South Africa’s “Rainbow Nation” was to be its centrepiece: out with authoritarianism, racism, ethnocentrism, etc., and in with multiracialism, multiethnicity, democracy and individual liberty. We could all leave the past where it belonged (in the past) and live in peace and harmony, as democracy would defend it, secure it, and preserve it. South Africa would lead the way, and would in fact teach us westerners how it is to be done.

Oddly enough, South Africa quickly fell off of the radar of mainstream media in the West when it failed to live up to these lofty goals. Rather than living up to the hype of being the “Rainbow Nation”, it instead was quickly mired in the politics of corruption and race, showing itself to be all too human, just like the rest of us. South Africa had failed to immediately resolve its inherent internal tensions, whether they be racial, economic, ethnic, or ideological, and by extension it had failed to deliver its promise to western liberals. “Out of sight, out of mind” became the best practice, replacing the utopianism of the first half of the 1990s.

Granted, a lot of grace was given to South Africa by western media so long as Nelson Mandela remained in office (and even after that), but the failures were plainly evident to see: an explosion in crime and in corruption were its most obvious characteristics, ones that could not be brushed under the carpet. The African National Congress (ANC), the party that would deliver the promise of the Rainbow Nation, was instead shown to be little more than a powerful engine of corruption and patronage. Luckily for the ANC, it was fueled in large part by the legacy of Mandela and the goodwill that he had accumulated over the years while he sat in prison.

The post-Mandela era has not been kind to the ANC (nor to South Africa as a whole), as the party could no longer hide behind his fading legacy, and could no longer cash in on the goodwill that came from it. It could “put up”, and would it not “shut up”. The ANC over time became a lumbering beast, too big to slay, but too slow to destroy its opposition when compared to its nimble youth.

What has the party delivered in its three decades of power? It did help dismantle Apartheid, but it did not deliver economic prosperity and opportunity to all. Instead, it simply swapped out elites where it could, preferring to keep the new ones in house. An inability to tame crime and to keep the national power grid running has turned the country into a bit of a joke, especially when it is lumped into the BRICS group alongside Brazil, Russia, India, and China. Despite its abundance of natural wealth, South Africa has been economically mismanaged.

South Africa is an important country to watch for the simple reason that there is so much tinder lying around, ready to be set ablaze. Luckily for South Africans, dire projections of widespread civil strife have not come to pass. Unluckily for South Africans, their national trajectory is headed in the wrong direction. Last week’s national elections saw the ANC lose their parliamentary majority for the first time ever, and the only way to read the results is to conclude that no matter how one may feel about this very corrupt party, it is an ominous sign.

May 29, 2024

A visit to failure pier

CDR Salamander has some advice for any US congresscritter with a spine (unfortunately, that probably means none of them):

This old operational planner has one bit of advice to Congress in their role of having oversight of the Executive Branch; subpoena the Decision Brief for the Gaza pier operation.

This was on the lowest of low scale of military operations, Humanitarian Assistance/Disaster Response. There is little to nothing classified about any of this rump of a capability. Call in member of the Joint Staff who were involved in this planning — and I would prefer if you could find a few terminal O5/6 to testify as well. You might actually enjoy some candor.

The Commander’s Intent, the Higher Direction and Guidance, the Planning Assumptions, the Constraints and Restraints, the Critical Vulnerability analysis, etc. It is all there. If not, the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and the Secretary of Defense should tell the American people to their face.

This is a larger issue than anything happening in that impossible corner of the globe. Over the weekend, we saw yet more indications of an empire in decline deteriorating from bad to pathetic.

From the time the first load came off the pier, the aid barely made it past 300 meters until it disappeared into Hamasistan.

I’ll go ahead and tap the sign;

[…]

Generally this latest act in this other-end-of-the-Med-from-the-Greeks tragedy that has unfolded in front of everyone. As we saw at the top at Ashkelon Beach, first some ancillary bits floated over to Israel as the Eastern Mediterranean reminded everyone it is at the eastern end of a big sea with weather and waves and stuff.

We then found out that three soldiers were injured in a forklift accident. Just to add insult to injury, as the locals laughed, it appears more of the business end decided to try to make it to Haifa on its own.

[…]

I’m not sure how you scatter Army property all over the Eastern Med without a boot getting dry, but maybe I’m wrong. Gaza is lava, and all.

Empires don’t often die in a blaze of glory, no. More often than not they end in simpering apologies and excuses from poor leaders putting the wrong people in positions they have no place being, and when they fail — there is no accountability.

May 26, 2024

“Naked ‘gobbledygook sandwiches’ got past peer review, and the expert reviewers didn’t so much as blink”

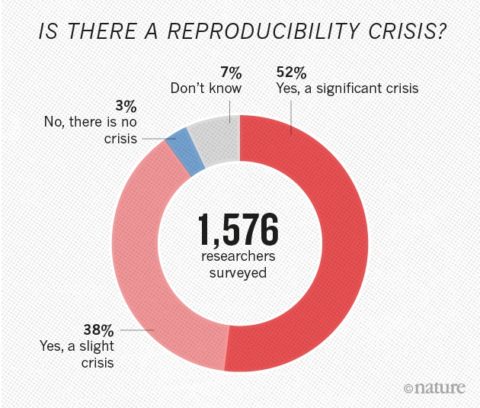

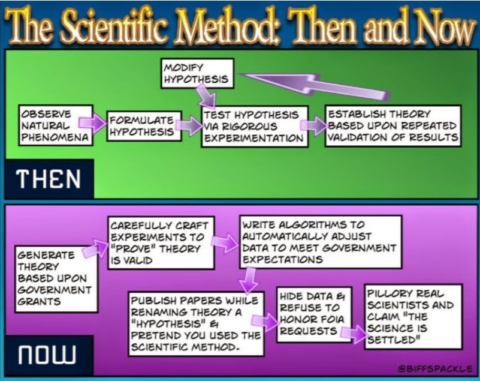

Jo Nova on the state of play in the (scientifically disastrous) replication crisis and the ethics-free “churnals” that publish junk science:

Proving that unpaid anonymous review is worth every cent, the 217 year old Wiley science publisher “peer reviewed” 11,300 papers that were fake, and didn’t even notice. It’s not just a scam, it’s an industry. Naked “gobbledygook sandwiches” got past peer review, and the expert reviewers didn’t so much as blink.

Big Government and Big Money has captured science and strangled it. The more money they pour in, the worse it gets. John Wiley and Sons is a US $2 billion dollar machine, but they got used by criminal gangs to launder fake “science” as something real.

Things are so bad, fake scientists pay professional cheating services who use AI to create papers and torture the words so they look “original”. Thus a paper on “breast cancer” becomes a discovery about “bosom peril” and a “naïve Bayes” classifier became a “gullible Bayes”. An ant colony was labeled an “underground creepy crawly state”.

And what do we make of the flag to clamor ratio? Well, old fashioned scientists might call it “signal to noise”. The nonsense never ends.

A “random forest” is not always the same thing as an “irregular backwoods” or an “arbitrary timberland” — especially if you’re writing a paper on machine learning and decision trees.

The most shocking thing is that no human brain even ran a late-night Friday-eye over the words before they passed the hallowed peer review and entered the sacred halls of scientific literature. Even a wine-soaked third year undergrad on work experience would surely have raised an eyebrow when local average energy became “territorial normal vitality”. And when a random value became an “irregular esteem”. Let me just generate some irregular esteem for you in Python?

If there was such a thing as scientific stand-up comedy, we could get plenty of material, not by asking ChatGPT to be funny, but by asking it to cheat. Where else could you talk about a mean square mistake?

Wiley — a mega publisher of science articles has admitted that 19 journals are so worthless, thanks to potential fraud, that they have to close them down. And the industry is now developing AI tools to catch the AI fakes (makes you feel all warm inside?)

Fake studies have flooded the publishers of top scientific journals, leading to thousands of retractions and millions of dollars in lost revenue. The biggest hit has come to Wiley, a 217-year-old publisher based in Hoboken, N.J., which Tuesday will announce that it is closing 19 journals, some of which were infected by large-scale research fraud.

In the past two years, Wiley has retracted more than 11,300 papers that appeared compromised, according to a spokesperson, and closed four journals. It isn’t alone: At least two other publishers have retracted hundreds of suspect papers each. Several others have pulled smaller clusters of bad papers.

Although this large-scale fraud represents a small percentage of submissions to journals, it threatens the legitimacy of the nearly $30 billion academic publishing industry and the credibility of science as a whole.

May 10, 2024

A different take on the Russo-Ukrainian War

Kulak suggests that far from being a model for future wars, the ongoing conflict in Ukraine may not prefigure anything at all about future wars:

Few weeks go by where I don’t read a piece on how Ukraine is the Future of warfare and armies and thinkers need to adjust to the reality that the warfare of the future will involve massive unaccountable amounts of artillery, trenches, conscription and grinding warfare.

While sometimes they point to relevant lessons: Yes the inability of the US to quickly reindustrialize and produce artillery shells at a rate comparable to Russia does speak to a profound rot in American governance, the military industrial complex, and American business regulation more generally,

Often times the conclusions drawn are dangerously delusional: A draft would be more likely to break the American nation than save it. As indeed conscription has resulted in Ukraine’s population collapsing with somewhere between 6 and 10 million Ukrainians (out of a pre-war 36 million) having fled the country, not to escape the mostly static war, but to escape the Totalitarian conditions the Zelensky regime has imposed in response to the war. (1.1 million of whom escaped INTO Russia, for any who deny this [is] largely an ethnic conflict between Western and Russian Ukrainians, as it has been since 2014).

And the thing is all of these discussions rest on a assumption that seems ludicrous the second you stop and think about it: Ukraine is not the future of Warfare, these conditions will be almost impossible to ever create again.

Ukraine had a pre-war Nominal GDP of 199 billion USD. Officially this only declined to 160 billion in 2022 as a result of the war, but there’s good reason to think its actual internal private sector economy collapsed far further [given] it had collapsed from 177 billion in 2013 to 90 billion in 2015 as a result of the US backed Coup/Revolution.

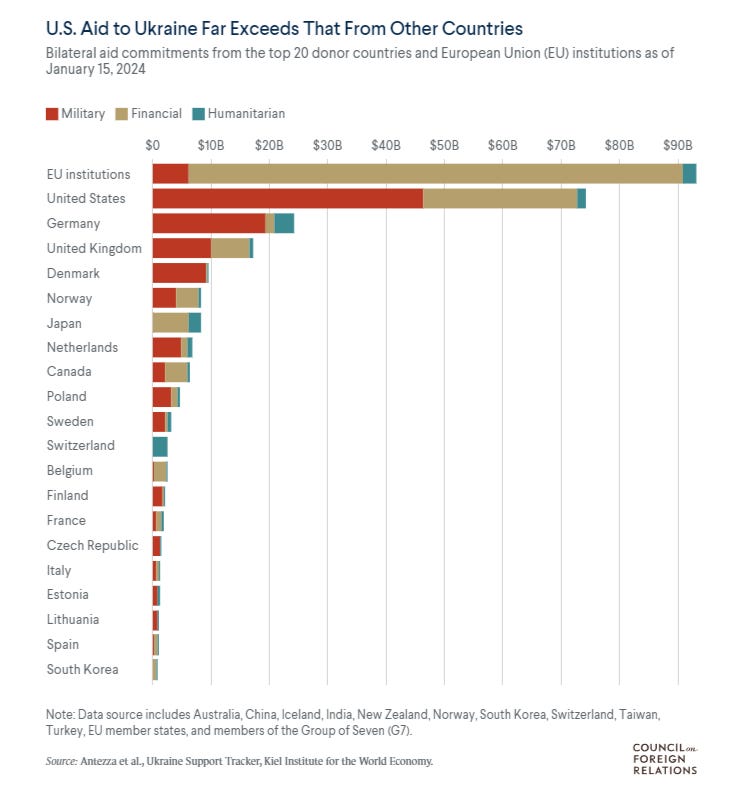

Indeed given the population flight, conscription, and impositions on the populace, it is very likely a SUPER-MAJORITY of that 160 billion GDP in 2022, was actually the result of US and NATO pouring hundreds of billions into the country. Where it was either used or siphoned off as corruption.

Simply put Ukraine has received military, financial and other aid most like in excess of what its entire internal economy produced in the same period, and as of writing it’s still losing territory.

When commentators say this is a war between NATO and Russia they are almost entirely correct. If you combine all the economies that are funding, arming, or fighting on one side or the other of this war you get a majority of the entire global economy.

And they have used all that money to pay off the Ukrainian regime to refuse any peace agreement, even ones their own negotiators had agreed to, and that were clearly in the best interest of the country … you know if you value hundreds of thousands of young men and not having your population collapse more than narrow stretches of land being bought up by Blackrock.

May 4, 2024

Process optimization can definitely be taken too far

Freddie deBoer considers systems that have been overoptimized to the detriment of most users and the benefit of a small, privileged minority:

I know a guy who used to make his living as an eBay reseller. That is, he’d find something on eBay that he thought was underpriced so long as the auction didn’t go above X dollars, buy it, then resell it for more than he paid for it Classic imports-exports, really, a digital junk shop. Eventually he got to the point where, with some items, he didn’t ever have physical possession of them; he had figured out a way to get them directly from whoever he bought an item from to the person he had sold the item to, while still collecting his bit of arbitrage along the way. This buying and selling of items on eBay, looking for deals, was sufficient to be his full-time job and pay for a mortgage. But the last time I saw him, a few years ago, he had gotten an ordinary office job. He told me that it had become too difficult to find value; potential sellers and buyers alike had access to too many tools that could reveal the “real” price of an item, and there was little delta to eke out. He’s not alone. If you search around in eBay-related forums, you’ll find that many longtime sellers have reached similar conclusions. The hustle just doesn’t work anymore.

I don’t suppose there’s any great crime there — it’s all within the rules. And there does appear to still be an eBay-adjacent reselling economy; it’s just that, as far as I can glean, it’s driven by algorithms and bots that average resellers simply don’t have access to. It appears that some super-resellers have implemented software solutions to identify underpriced goods and buy them automatically and algorithmically. They have optimized the system for their own use, giving them an advantage, putting other sellers at a disadvantage, and arguably hurting buyers by eliminating uncertainty that sometimes results in lower-than-optimal-to-sellers prices. This is all in sharp contrast to the early years, when my friend would keep listings for lucrative product categories open – in separate windows, not tabs, that’s how long ago this was – and refresh until he found potential moneymakers. That sort of human searching and bidding work stands at a sharp disadvantage compared to those with information-scraping capacity and automated tools. It’s a good example of how access to data has left systems overoptimized for some users. One of the things that the internet is really good at is price discovery, and these digital tools help determine the “optimal” price of items on eBay, which results in less opportunity for arbitrage for other players.

My current working definition of overoptimization goes like this: overoptimization has occurred when the introduction of immense amounts of information into a human system produces conditions that allow for some players within that system to maximize their comparative advantage, without overtly breaking the rules, in a way that (intentional or not) creates meaningful negative social consequences. I want to argue that many human systems in the 2020s have become overoptimized in this way, and that the social ramifications are often bad.

Getting a restaurant reservation is a good example. Once upon a time, you called a restaurant’s phone number and asked about a specific time and they looked in the book and told you if you could have that slot or not. There was plenty of insiderism and petty corruption involved, but because the system provided incomplete information that was time consuming to procure, there was a limit to how much you could game that system. Now that reservations are made online, you can look and see not only if a specific slot has availability but if any slots have availability. You can also make highly-educated guesses about what different slots are worth on the market through both common sense (weekend evenings are the most valuable etc) and through seeing which reservations get snapped up the fastest in an average week. And being online means that the reservation system is immediate and automatic, so you can train a bot to grab as many reservations as you want, near-instantaneously, and you can do so in a way that the system doesn’t notice. (Unlike, say, if you called the same restaurant over and over again and tried to hide your voice by doing a series of fake accents.) The outcome of all this is that getting a reservation at desirable places is a nightmare and results in a secondary market that, like seemingly everything in American life, is reserved for the rich. The internet has overoptimized getting a restaurant reservation and the result is to make it more aggravating and less egalitarian.

As has been much discussed, nearly the exact same scenario has made getting concert tickets a tedious and ludicrously-pricy exercise in frustration.

April 21, 2024

Publius Rutilius Rufus, an honest man in a dishonest era

Lawrence W. Reed discusses the life and career of Publius Rutilius Rufus, Roman consul and historian, who suffered the revenge of corrupt tax farmers (publicani) after attempting to protect taxpayers from extortion in the province of Asia:

In the last decades of the Roman Republic, as its liberties crumbled and the dictatorship of the subsequent Empire loomed, honesty decayed with each successive generation—an omen we should think long and hard about today. Among the lessons of the Roman experience is this: Liberty is ultimately incompatible with widespread indifference to truth. A society of liars succumbs to the tyrant who brings “order” to its chaos and corruption.

In a book I strongly recommend, The Lives of the Stoics: The Art of Living from Zeno to Marcus Aurelius, authors Ryan Holiday and Stephen Hanselman tell us about a man named Publius Rutilius Rufus (158 B.C.-78 B.C.). They regard him as “the last honest man” of the dying Republic. Though that description surely contains ample hyperbole to emphasize a point, Rufus’s exceptional honesty was indeed notable in his day because it was no longer the rule in a decadent age. As Mark Twain would note many centuries later, “an honest man in politics shines more than he would elsewhere”.

Rufus, the great-uncle of Julius Caesar (his sister Rutilia was Caesar’s maternal grandmother), built an illustrious career in the Roman military. Those under his command were known as “the best trained, the most disciplined, and the bravest” of the legions. He garnered enormous respect because of his Stoic virtues — courage, temperance, wisdom, and justice. In 105 B.C., he served in the highest political post in the Republic, the consulship. He was incorruptible, which meant he was a target of those who weren’t.

It had become a common practice in the late Republic for the government to hire private contractors to collect taxes. These “publicani” often extorted more from their victims than the taxes required because that’s the way the contracts were written. The government didn’t care what the publicani kept for themselves if it got its expected revenues. When Rufus attempted to stop the injustices this arrangement created, the publicani and their allies in the Roman Senate fought back. They arranged a sham trial with a pre-ordained verdict and charged Rufus with the very thing of which they themselves were guilty: extortion and corruption.

Historian Tom Holland in Rubicon: The Last Years of the Roman Republic writes that Rufus’s conviction was “the most notorious scandal in Roman legal history” and “an object lesson in how dangerous it could be to uphold ancient values against the predatory greed of corrupt officials”. With utterly no evidence and all credible testimony to the contrary, the accusers claimed Rufus had extorted money from Smyrna in the Roman province of Asia (what is now western Turkey).

Another historian, Mike Duncan, notes, “The charges were ludicrous as Rutilius [Rufus] was a model of probity and would later be cited by Cicero as the perfect model of a Roman administrator”.

As punishment for his trumped-up offense, Rufus was sent into exile but in deference to his past service, the court gave him the option of choosing where that would be. He chose Smyrna, the place he was charged with victimizing. When he arrived there, he was celebrated as the man who had tried to end the very practices of which he was wrongly convicted. Ryan Holiday and Stephen Hanselman describe what happened to Rufus as “a very old trick”:

Accuse the honest man of precisely the opposite of what they’re doing, of the sin you yourself are doing. Use their reputation against them. Muddy the waters. Stain them with lies. Run them out of town by holding them to a standard that if equally applied would mean the corrupt but entrenched interests would never survive … Smyrna, grateful for the reforms and scrupulous honesty of the man who had once governed them, welcomed [Rufus] with open arms … Cicero would visit there in 78 B.C. and call him “a pattern of virtue, of old-time honor, and of wisdom”.

March 21, 2024

QotD: South Africa under Thabo Mbeki

[During Nelson Mandela’s presidency, Thabo] Mbeki quickly began to insist that South Africa’s military, corporations, and government agencies bring their racial proportions into exact alignment with the demographic breakdown of the country as a whole. But as Johnson points out, this kind of affirmative action has very different effects in a country like South Africa where 75% of the population is eligible than it does in a country like the United States where only 13% of the population gets a boost. Crudely, an organization can cope with a small percentage of its staff being underqualified, or even dead weight. Sinecures are found for these people, roles where they look important but can’t do too much harm. The overall drag on efficiency is manageable, especially if every other company is working under the same constraints.

Things look very different when political considerations force the majority of an organization to be underqualified (and there are simply not very many qualified or educated black South Africans today, and there were even fewer when these rules went into effect). A shock on that scale can lead to a total breakdown in function, and indeed this is precisely what happened to one government agency after another. Johnson notes that this issue, and particularly its effects on service provision to the rural poor, pit two constituencies against each other which many have tried to conflate, but are actually quite distinct. The immiserated black lower class (which the ANC purported to represent) didn’t benefit at all from affirmative action because they weren’t eligible for government jobs anyway, and they vastly preferred to have the whites running the water system if it meant their kids didn’t get cholera. The people actually benefited by Mbeki’s affirmative action policies were the wealthy and upwardly-mobile black urban bourgeoisie, a tiny minority of the country, but one that formed the core of Mbeki’s support.

That same small group of educated and well-connected black professionals was also the major beneficiary of Mbeki’s other signature economic policy: Black Economic Empowerment (BEE). Oversimplifying a bit, BEE was a program in which South African corporations were bullied or threatened into selling some or all of their shares at favorable prices to politically-connected black elites, who generally returned the favor by looting the company’s assets or otherwise running it into the ground (note that this is not the description you will find on Wikipedia). The whole thing was so astoundingly, revoltingly corrupt that even the ANC has had to back off and admit in the face of criticism from the left that something went wrong here.

What made BEE so “successful” is that it was actually far more consensual than you might have guessed from that description. In many cases, the white former owners of these corporations were looking around at the direction of the country and trying to find any possible excuse to unload their assets and get their money out. The trouble was that it was difficult to do that without seeming racist, because obviously racism was the only reason anybody could have doubts about the wisdom of the ANC. The genius of BEE is that it allowed these white elites to perform massive capital flight while simultaneously framing it as a grand anti-racist gesture and a mark of their confidence in the future of the country.

This is one particular instance of a more general phenomenon, which is that at this stage pretty much everybody was pretending that things were going great in South Africa, when things were clearly not, in fact, going great. But this was the late 90s and early 00s, the establishment media had a much tighter hold on information than it does today, and so long as nobody had an interest in the story getting out, it wasn’t going to get out. Everybody who mattered in South Africa wanted the story to be that the end of apartheid had resulted in a peaceful and harmonious society, and everybody outside South Africa who’d spent decades supporting and fundraising for the ANC wanted this to be the story too.

John Psmith, “REVIEW: South Africa’s Brave New World, by R.W. Johnson”, Mr. and Mrs. Psmith’s Bookshelf, 2023-03-20.

January 12, 2024

“… normal people no longer trust experts to any great degree”

Theophilus Chilton explains why the imprimatur of “the experts” is a rapidly diminishing value:

One explanation for the rise of midwittery and academic mediocrity in America directly connects to the “everybody should go to college” mantra that has become a common platitude. During the period of America’s rise to world superpower, going to college was reserved for a small minority of higher IQ Americans who attended under a relatively meritocratic regime. The quality of these graduates, however, was quite high and these were the “White men with slide rules” who built Hoover Dam, put a man on the moon, and could keep Boeing passenger jets from losing their doors halfway through a flight. As the bar has been lowered and the ranks of Gender and Queer Studies programs have been filled, the quality of college students has declined precipitously. One recent study shows that the average IQ of college students has dropped to the point where it is basically on par with the average for the general population as a whole.

Another area where this comes into play is with the replication crisis in science. For those who haven’t heard, the results from an increasingly large number of scientific studies, including many that have been used to have a direct impact on our lives, cannot be reproduced by other workers in the relevant fields. Obviously, this is a problem because being able to replicate other scientists’ results is sort of central to that whole scientific method thing. If you can’t do this, then your results really aren’t any more “scientific” than your Aunt Gertie’s internet searches.

As with other areas of increasing sociotechnical incompetency, some of this is diversity-driven. But not wholly so, by any means. Indeed, I’d say that most of it is due to the simple fact that bad science will always be unable to be consistently replicated. Much of this is because of bad experimental design and other technical matters like that. The rest is due to bad experimental design, etc., caused by overarching ideological drivers that operate on flawed assumptions that create bad experimentation and which lead to things like cherry-picking data to give results that the scientists (or, more often, those funding them) want to publish. After all, “science” carries a lot of moral and intellectual authority in the modern world, and that authority is what is really being purchased.

It’s no secret that Big Science is agenda-driven and definitely reflects Regime priorities. So whenever you see “New study shows the genetic origins of homosexuality” or “Latest data indicates trooning your kid improves their health by 768%,” that’s what is going on. REAL science is not on display. And don’t even get started on global warming, with its preselected, computer-generated “data” sets that have little reflection on actual, observable natural phenomena.

“Butbutbutbut this is all peer-reviewed!! 97% of scientists agree!!” The latter assertion is usually dubious, at best. The former, on the other hand, is irrelevant. Peer-reviewing has stopped being a useful measure for weeding out spurious theories and results and is now merely a way to put a Regime stamp of approval on desired result. But that’s okay because the “we love science” crowd flat out ignores data that contradict their presuppositions anywise, meaning they go from doing science to doing ideology (e.g. rejecting human biodiversity, etc.). This sort of thing was what drove the idiotic responses to COVID-19 a few years ago, and is what is still inducing midwits to gum up the works with outdated “science” that they’re not smart enough to move past.

If you want a succinct definition of “scientism,” it might be this – A belief system in which science is accorded intellectual abilities far beyond what the scientific method is capable of by people whose intellectual abilities are far below being able to understand what the scientific method even is.

December 17, 2023

How RFK, Jr. helped destroy British Columbia’s resource-based economy

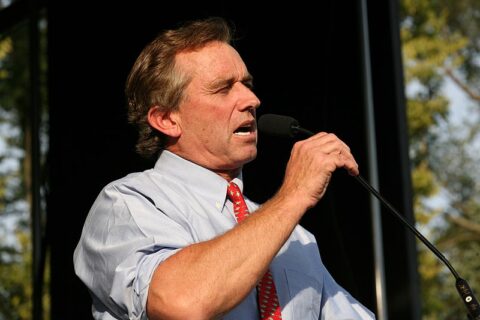

Elizabeth Nickson found herself added to one of Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s fundraising mailing lists:

Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. speaking in Urbana, Illinois on October 14, 2007.

Photo by Daniel Schwen via Wikimedia Commons.

I am on RFKJr’s campaign mailing list, probably through Children’s Health Defence and they asked me for money, and I said sure, just as soon as he fixes the catastrophe he caused in the province where I live.

Got a message back!

It read, “Elizabeth, I am sure Robert would fix whatever harm he caused, can you explain?”

No problem, I said.

1. In British Columbia, we had the largest industrial forest in the world

2. It paid for education and universal “free” health care.

3. The environmental left decided to shut it down.

4. The reason for their protest was that the government, as was common practice, had sold cutting permits with long leaseholds. A new socialist government announced it was pulling the permits and taking those forests back.

5. In order not to lose all the invested money, which they had not only paid for upfront and in annual leasing charges, but paid taxes on, some for decades, lessees immediately clear cut their lands. Clear cuts are ugly. (but they are fire breaks)

6. That triggered the protest.

7. RFK Jr came in under RiverKeepers and supercharged the protest. His celebrity and glamour made the protest major international news. I was in London, I heard about it. More kids joined the protest. And then more and more. Until the government caved. Would it have happened without his presence? I do not think so. He gave very young people who had no access to power, nor any hope of it, ever, a very heady hit of significance and their lives took on huge huge meaning. For many it remains the high point of their lives. Because for the province, it was all downhill from there. All promise vanished and a grinding slow growth followed.

8. Over the ensuing ten years, cutting was diminished and heavy regulation covered the rest. By 2002, written regulations piled on top of each other stood seven feet high, taller than a man.

9. Forested communities died.

10. 100,000 families lost their livelihood.

11. Resource jobs have huge multipliers, not only forested towns died, so did regional metropolitan centers. Greens, replete with success, hit other resource industries – mining, ranching – which died. More families bankrupted.

12. They were told to go into tourism.

13. Which pays minimum wage and can only support a family if everyone, even the children, work. And, it’s seasonal.

14. Over time, the unmanaged forests became clogged with overgrowth, little trees like carrots pulled all the water from the forest floor, desiccated the soil and then pulled water from aquifers. The forests became tinder. And increasingly every summer, they explode in fire.

15. The government needed money.

16. Casinos provided it.

17. Asian cartels – you cannot imagine how violent they are – moved in and used the casinos to launder most of the drug money from North America. They bribed immigration, they bribed city government, they threatened anyone who tried to stand in their way.

18. They were so successful, human trafficking and child sex trafficking shot up. We have the second largest port on the west coast of North and South America. Through it streams container loads of drugs and trafficked children and women. At the port, you just stand aside, if you want to live. You think most of the fentanyl comes in through Mexico? Nope. It comes in through us.

19. The cartels do pay taxes. You think Black Rock is bad? These guys kill if they don’t get what they want. They are buying every business they can, to launder money through. The cartels also launder money through real estate in the city. That means housing is insanely expensive and property taxes are sky high. Canadians can’t afford to buy houses or live in the ones they own. A family making a median income has to pay 100% of income to buy a median priced house.

20. Crime is a) a driver of the economy and b) a principal source of government revenue.

21. Green has destroyed the province.

And that, I am afraid, is what celebrities do. It is why they are so hated, and one of the reason Hollywood is dying. They destroy the lives of ordinary men and women, and then move on to greater heights. Their lives are so privileged, they have absolutely no idea how people make money. And RFKJr, mind-numbingly privileged from birth, is the same. When asked about climate change, he says it’s happening but taxes won’t work. “Regenerative agriculture” he says, vaguely. It is true, regenerative agriculture could capture a lot of carbon, the amount debatable but it has promise. But cutting regulation? He has no, zero, absolutely no idea of how regulation punishes the non-elites. His is a black hole of ignorance and that is common; a majority have zero idea. Zero.

October 23, 2023

QotD: The real meaning of “Watergate”

I was reflecting this week on my brief stint, many years ago, as a newspaperman. It was a job I loved. I signed on not too many years after the Watergate scandal, and journalists were still flush with heroic ideas about themselves. Woodward and Bernstein — and all reporters by extension — had toppled a corrupt presidency and saved the republic and the Constitution from the kind of behind-the-scenes government tyranny dramatized in such thriller films as The Parallax View and Three Days of the Condor.

[…]

Recently, reading Mark Levin’s Unfreedom of the Press, I was reminded that, before reporters went on their great crusade against Richard Nixon, they had overlooked a whole lot of corruption in the Democrat presidents who preceded him.

Levin tells how John F. Kennedy, with the knowledge of his brother and Attorney General Robert, nudged the IRS into auditing conservative groups. With Kennedy’s approval, the FBI was also employed to investigate those the administration disliked, including Martin Luther King Jr. Lyndon Baines Johnson would later increase the politically motivated auditing and spying. None of this was uncovered until later on.

Ben Bradlee — the editor of the Washington Post, where Woodward and Bernstein broke the Watergate story — was well aware of his pal Kennedy’s misuse of the tax and investigative agencies. Not only did he not report it, he allowed himself and his paper to be manipulated by information JFK had wrongly obtained.

This totally changes the Watergate narrative. Nixon’s dirty tricks and enemy lists may have been creepy and wrong, but the press exposure of these misdemeanors came after years of ignoring similar and worse malfeasance by Democrat administrations.

That changes what Watergate means. That transforms it from a heroic crusade into a political hit job, Democrat hackery masquerading as nobility. The press turned a blind eye to the corruption of JFK and LBJ, then raced to overturn the election of a man they despised — despised in part because he battled the Communism many of them had espoused.

Andrew Klavan, “‘Watergate’ Doesn’t Mean What the Press Thinks It Means: The press turned a blind eye to the corruption of JFK and LBJ, then raced to overturn the election of a man they despised”, The Daily Wire, 2019-08-31.