World War Two

Published 13 Jul 2024Japan is aware that soon enough the Allies will invade the Home Islands, and they will mobilize absolutely everything and everyone they can for their defense plan, “The Glorious Death of the 100 Million”. In the meantime, Allied carrier forces keep hitting them, the Australian advance on Borneo continues, the Chinese advance on Guilin continues, the Allied rebuilding of Okinawa continues, and American preparations are nearly complete for a test detonation of an atomic bomb.

(more…)

July 14, 2024

Japan’s New Defense plan, 100 million dead – WW2 – Week 307 – July 13, 1945

July 6, 2024

QotD: The Roman Republic at war … many wars … many simultaneous wars

With the end of the Third Samnite War in 290 and the Pyrrhic War in 275, Rome’s dominance of Italy and the alliance system it constructed was effectively complete. This was terribly important because the century that would follow, stretching from the start of the First Punic War in 264 to the end of the Third Macedonian War in 168 (one could argue perhaps even to the fall of Numantia in 133) put the Roman military system and the alliance that underpinned it to a long series of sore tests. This isn’t the place for a detailed recounting of the wars of this period, but in brief, Rome would fight major wars with three of the four other Mediterranean great powers: Carthage (264-241, 218-201, 149-146), Antigonid Macedon (214-205, 200-196, 172-168, 150-148) and the Seleucid Empire (192-188), while at the same time engaged in a long series of often quite serious wars against non-state peoples in Cisalpine Gaul (modern north Italy) and Spain, among others. It was a century of iron and blood that tested the Roman system to the breaking point.

It certainly cannot be said of this period that the Romans always won the battles (though they won more than their fair share, they also lost some very major ones quite badly) or that they always had the best generals (though, again, they tended to fare better than average in this department). Things did not always go their way; whole armies were lost in disastrous battles, whole fleets dashed apart in storms. Rome came very close at points to defeat; in 242, the Roman treasury was bankrupt and their last fleet financed privately for lack of funds (Plb. 1.59.6-7). During the Second Punic War, at one point the Roman censors checked the census records of every Roman citizen liable for conscription and found only 2,000 men of prime military age (out of perhaps 200,000 or so; Taylor (2020), 27-41 has a discussion of the various reconstructions of Roman census figures here) who hadn’t served in just the previous four years (Liv. 24.18.8-9). In essence the Romans had drafted everyone who could be drafted (and the 2,000 remainders were stripped of citizenship on the almost certainly correct assumption that the only way to not have been drafted in those four years but also not have a recorded exemption was intentional draft-dodging).

And the military demands made on Roman armies and resources were exceptional. Roman forces operated as far east as Anatolia and as far west as Spain at the same time. Livy, who records the disposition of Roman forces on a year-for-year basis during much of this period (we are uncommonly well informed about the back half of the period because those books of Livy mostly survive), presents some truly preposterous Roman dispositions. Brunt (Italian Manpower (1971), 422) figures that the Romans must have had something like 225,000 men under arms (Romans and socii) each year between 214 and 212, immediately following a series of three crushing defeats in which the Romans probably lost close to 80,000 men. I want to put that figure in perspective for a moment: Alexander the Great invaded the entire Persian Empire with an army of 43,000 infantry and 5,500 cavalry. The Romans, having lost close to Alexander’s entire invasion force twice over, immediately raised more than four times as many men and kept fighting.

These armies were split between a bewildering array of fronts (e.g. Liv 24.10 or 25.3): multiple armies in southern Italy (against Hannibal and rebellious socii now supporting him), northern Italy (against the Cisalpine Gauls, who also backed Hannibal) and Sicily (where Syracuse threatened revolt) and Spain (a Carthaginian possession) and Illyria (fighting the Antigonids) and with fleets active in both the Adriatic and Tyrrhenian Sea supporting those operations. And of course a force defending Rome itself because did I mention Hannibal was in Italy?

If you will pardon me embellishing a Babylon 5 quote, “Only an idiot fights a war on two fronts. Only the heir to the throne of the kingdom of idiots would fight a war on twelve fronts.” And apparently, only the Romans would then win that war anyway.

(I should note that, for those interested in reading up on this, the state-of-the-art account of Rome’s ability to marshal these truly incredible amounts of resources and especially men is the aforementioned, M. Taylor, Soldiers & Silver (2020), which presents the consensus position of scholars better than anything else out there. I’d be remiss if I didn’t note that my own book project takes aim at this consensus and hopes to overturn parts of it, but seeing as how my book isn’t done, for now Taylor holds the field (also it’s a good book which is why I recommended it)).

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: The Queen’s Latin or Who Were the Romans, Part II: Citizens and Allies”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2021-06-25.

May 28, 2024

Rishi Sunak’s big-brained election-winning strategy: bring back the draft

Embattled British Conservative leader Rishi Sunak has had another of his patented brainstorms for a policy that will absolutely win his party huge numbers of “gammon” votes in the July 4th general election:

Here we go: straight off, let’s get the youth to do some indentured servitude, sorry, National Service.

The Sunday Times reports:

Every 18-year-old will be required by law to sign up for a year of National Service under plans unveiled by the Conservatives this weekend.

Rishi Sunak’s first manifesto commitment would see youngsters given the choice between a full-time course (for 12 months) or spending one weekend a month volunteering in their community. There will be sanctions for teenagers who do not take part. Up to 30,000 full-time positions will be created either in the armed forces or in cybersecurity training. The weekend placements could be with the fire or police service, the NHS or charities tackling loneliness and supporting older, isolated people.

The Tories have pledged to set up a royal commission to design the £2.5billion programme and establish details such as how the cybertraining would be delivered. A pilot will start next year and by the end of the parliament legislation will be passed making it mandatory for all 18-year-olds.

[…]

The Prime Minister says: “This new, mandatory National Service will provide life-changing opportunities for our young people, offering them the chance to learn real-world skills, do new things and contribute to their community and our country.” I doubt very much it will do this. The youth could learn real world skills in a weekend job that they’d actually get paid for but under Tory Rule they must become an indentured servant of the State instead.

It was floated that “the weekend placements could be with the fire or police service, the NHS or charities tackling loneliness and supporting older, isolated people”. Really? The fire and police service having to babysit some surly 17-year-old teenager glued to a mobile phone? Is this really what a police officer wants?

No doubt the vast majority of the youth will be dumped in some NHS hospital to do goodness knows what, or indeed a nursing home. And what about all the people who are currently off work and on anti-depressants “because of mental health”. Will they be forced to volunteer, or let off the requirement?

May 15, 2024

QotD: Recruiting an army in the Roman Republic

… once elected and inaugurated, the consuls select the day of the dilectus. Polybius is quite wordy in his description of the process, but it gives us a nice schematic vision of the process. In practice, there are two groups here to keep track of in parallel: the dilectus of Roman citizens, but also the mobilization of the socii who will reinforce those Roman legions once raised. The two processes happen at the same time.

So, on the appointed day(s), Polybius tells us all Romans liable for service of military age assemble in Rome and are called up on the Capitoline Hill for selection. This was a point that raised a lot of skepticism from historians,1 mostly concerning the number of people involved, but those concerns have all pretty much been resolved. While there might have been something like 323,000 Roman citizen males in the third or second century, they’re not all liable for general conscription, which was restricted to the iuniores – Roman citizen men between the ages of 17 and 46, who numbered fewer, probably around 228,000; seniores in theory could be conscripted, but in practice only were in an emergency. In practice the number is probably lower still as unless things were truly dire, men in their late 30s or 40s with several years of service could be pretty confident they wouldn’t be called and might as well stay home and rely on a neighbor of family member to report back in the unlikely event they were called. That’s still, of course, too many to bring up on to the Capitoline or to sort through calling out names, but as Polybius notes they don’t all come up, they’re called up by tribe. The Roman tribes were one of Rome’s two systems of voting units (the other, of centuries, we’ll come to in just a moment) and there were 35 of them, four urban tribes for those living in the city and 31 rural tribes for those living outside the city.

So what is actually happening is that the consul sets the date for the dilectus, then assigns his military tribunes to their legions (this matters because the tribunes will then do a round-robin selection of recruits to ensure each legion is of equivalent equality), then calls up one tribe at a time, with each tribe having perhaps around 6-7,000 iunores in it. Conveniently, the Capitoline is plenty large enough for that number, with estimates of its holding capacity tending to be between 12,000 and 25,000 or so.2 And while Polybius makes it seem like all of this happens on one day, it probably didn’t. Livy notes of one dilectus in 169, conducted in haste, was completed in 11 days; presumably the process was normally longer (though that’s 11 days for all three steps, not just the first one, Livy 43.14.9-10).

Once each tribe is up on the Capitoline, recruits are selected in batches; Polybius says in batches of four, but this probably means in batches equal to the number of legions being enrolled, as Polybius’ entire schema assumes a normal year with four legions being enrolled. Now Polybius doesn’t clarify how selection here would work and here Livy comes in awfully handy because we can glean little details from various points in his narrative (the work of doing this is a big chunk of Pearson (2021), whose reconstruction I follow here because I think it is correct). We know that the censors compile a list not just of Roman senators but of all Roman citizen households, including self-reported wealth and the number of members in the household, updated every five years. That self-reported wealth is used to slot Romans into voting centuries, the other Roman voting unit, the comitia centuriata; those centuries correspond neatly to how Romans serve in the army, with the equites and five classes of pedites (infantry). Because of a quirk of the Roman system, the top slice of the top class of pedites also serve on horseback, and Polybius is conveniently explicit that the censors select and record this too.

So at dilectus time, the consuls, their military tribunes (and their state-supplied clerk, a scriba) have a list of every Roman citizen liable for conscription, with the century and tribe they belong to, the former telling you what kind of soldier they can afford to be when called and the latter what group they’ll be called in. And we know from other sources (Valerius Maximus 6.3.4) that names are being read out, rather than just, say, selecting men at sight out of a crowd. That actually makes a lot of sense as dilectus (“select”) may really be dis-lego, “read apart”, from lego (-ere, legi, lectum) “to read”.3 And that matters because the other thing the Romans clearly have a record of us who has served in the past. We know that because in an episode that is both quite famous but also really important for understanding this process, in 214 – after four of the most demanding years of military activity in Roman history, due to the Second Punic War – the Roman censors identified 2,000 Roman iuniores who had not served in the previous four years (or claimed and been granted an exemption), struck them from the census rolls (in effect, revoking their citizenship) and then packed them off to serve as infantry (regardless of their wealth) in Sicily.4

So what happens as each tribe comes up is that the tribunes can call out the names – in batches – of men with the least amount of service, of the particular wealth categories they are going to need to fill out the combat roles in the legion.5 The tribunes for each legion pick one recruit from each batch that comes up, going round-robin so every legion gets the same number of first-picks. Presumably once the necessary fellows are picked out of one tribe, that tribe is sent down the Capitoline and the next called up.

Once that is done the oath is administered. This oath is the sacramentum militare; we do not have its text in the Republic (we do have the text for the imperial period), but Polybius summarizes its content that soldiers swear to obey the orders of the consuls and to execute them as best they are able. The Romans, being practical, have one soldier swear the full oath and then every other soldier come up and say, “like that guy said” (I’m not even really joking, see Polyb. 6.21.3) to get everyone all sworn in. Of course such an oath is a religious matter and so understood to be quite binding.

Then the tribunes fix a day for all of the new recruits to present themselves again (without arms, Polybius specifies) and dismiss them. Strikingly, Polybius only says they are dismissed at this point – not, as later, dismissed to their homes. This makes me assume that the oath being described is administered tribe by tribe before the tribe is sent down (this also seems likely because fitting the last tribe and four legions worth of recruits on the Capitoline starts to get pretty tight, space-wise). Selecting with the various tribes might, after all, take a couple of days, so the tribunes might be telling the recruits of the first few tribes what day the entire legion will be assembled (that’ll be Phase II) after they’ve worked through all of the tribes. Meanwhile, once your tribe was called, you didn’t have to hang around in Rome any longer, if you weren’t selected you could go home, while the picked recruits might stick around in Rome waiting for Phase II.

That leads to the other logistical question for Phase I: the feasibility of having basically all of the iuniores in Rome for the process. Doubts about this have led to the suggestion that perhaps the dilectus in Rome was mirrored by smaller versions held in other areas of Roman territory in Italy (the ager Romanus) for Roman citizens out there. The problem with that assumption is that the text doesn’t support it. The Romans send out conscription officers (conquisitores) exactly twice that we know of, in 213 and 212 (Livy 23.32.19 and 25.5.5-9) and these are clearly exceptional responses to the failure of the dilectus in the darkest days of the Second Punic War (the latter is empowered to recruit under-age boys if they look strong enough to bear arms, for instance). But I also think it was probably unnecessary: this was a regular occurrence, so people would know to make arrangements for it and the city of Rome could prepare for the sudden influx of young men. This is, after all, also a city with regular “market days”, (the nundinae) which presumably would also cause the population to briefly swell, though not as much. And we’re doing this in an off-time in the agricultural calendar, so the farmhands can be spared.

Moreover, Rome isn’t that far away for most Romans. Strikingly, when the Romans do send out conquisitores, they split them with half working within 50 miles of Rome and half beyond that (Livy 25.5.5-9). The implication – that most of the recruits to be found are going to be within that 50 mile radius – is clear, and it makes a lot of sense given the layout of the ager Romanus. Certainly there were communities of Roman citizens farther out, but evidently not so many. Fifty miles down decent roads is a two-day walk; short enough that Roman iuniores could fill a sack with provisions, walk all the way to Rome, stay a few days for the first phase of the dilectus and walk all the way back home again at the end. We’re not told how communities farther afield might handle it, but they may well have trekked in too, or else perhaps sent a few young men with instructions to bring back a list of everyone who was called.

Meanwhile the other part of this phase is happening: the socii. Polybius reports that “at the same time the consuls send their orders to allied cities in Italy, which they with to contribute troops, stating the numbers required and the day and place at which the men selected must present themselves.”6 Livy gives us more clarity on how this would be done, providing in his description of the muster of 193 the neat detail that representatives of the communities of socii met with the consuls on the Capitoline (Livy 34.36.5). And that makes a ton of sense – this is happening at the same time as the selection, so that’s where the consuls are.

We also know the consuls have another document, the formula togatorum, which spells out the liability of each community of socii for recruits; we know less about this document than we might like. Polybius tells us that the socii were supposed to compile lists of men liable for recruitment (Polyb. 2.23-4) and an inscription of the Lex Agraria of 111 BC refers to, “the allies or members of the Latin name, from whom the Romans are accustomed to demand soldiers in the land of Italy ex formula togatorum“.7 That then supplies us with a name for the document. Finally, we know that in 177, some of the socii complained that many of the households in their territory had migrated into other communities but that they conscription obligations had not been changed (Livy 41.8), which tells us there was a formal system of obligations and it seems to have been written down in something called the formula togatorum, to which Polybius alludes.

What was written down? Really, we don’t know. It has been suggested that it might have been a sliding scale of obligations (“for every X number of Romans, recruit Y number of Paeligni”) or a standard total (“every year, recruit Y Paeligni”) or a maximum (“the total number of Paeligni we can demand is Y, plus one more guy whose job is to throw flags at things”.). In practice, it was clearly flexible,8 which makes me suspect it was perhaps a list of maximum capabilities from which the consuls could easily compute a fair enough distribution of service demands. A pure ratio doesn’t make much sense to me, because the socii come in their own units, which probably had normal sizes to them.

So, while the military tribunes are handling the recruitment of citizens into the legions, the consuls are right there, but probably focused on meeting with representatives of each community of the socii and telling them how many men Rome will need this year. Once told, those representatives are sent back to their communities, who handle recruitment on their own; Rome retains no conscription apparatus among the socii – no conscription offices, no records or census officials, nada. The consuls spell out how many troops they need and the rest of it was the socii‘s elected official’s problem.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: How To Raise a Roman Army: The Dilectus“, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2023-06-16.

1. Particularly in P.A. Brunt, Italian Manpower (1971).

2. Pearson (2021) compiles them; the issue is also discussed in Taylor (2020).

3. The philological argument here is Pearson (2021), 16-17. It is not air-tight because legere has a lot of meanings, including “to pick out” along with “to read”. That said, given that the verb of being recruited into the army is conscribere (“to write together, to conscript”), there really is a strong implication that this is a process with written records, which the rest of the evidence confirms. I think Pearson may or may not be right about the understood meaning of dilectus implying writing, but the process surely involved written records, as she argues.

4. A punishment post, this is also where the survivors of the Battle of Cannae were sent. Both groups remain stuck in Sicily until pulled into Scipio Africanus’ expedition to Africa in 205, so these fellows don’t get to go home and get their citizenship back until the conclusion of the war in 201.

5. In particular, we generally assume the lowest classes of Roman pedites probably could only afford to serve as light troops, the velites, while the wealthy equites had their own selection procedure for the cavalry done first. Of course, rich Romans not selected for the cavalry might serve as infantrymen if registered in the centuries of pedites which is presumably how Marcus Cato, son of the Censor, ends up in the infantry at Pydna (Plut. Aem. 21).

6. Polyb. 6.21.4. Paton’s trans.

7. Crawford, Roman Statutes (1996), 118 for the text of that inscription.

8. Something pointed out by L. de Ligt in his chapter in the Blackwell A Companion to the Roman Army (2007).

May 10, 2024

A different take on the Russo-Ukrainian War

Kulak suggests that far from being a model for future wars, the ongoing conflict in Ukraine may not prefigure anything at all about future wars:

Few weeks go by where I don’t read a piece on how Ukraine is the Future of warfare and armies and thinkers need to adjust to the reality that the warfare of the future will involve massive unaccountable amounts of artillery, trenches, conscription and grinding warfare.

While sometimes they point to relevant lessons: Yes the inability of the US to quickly reindustrialize and produce artillery shells at a rate comparable to Russia does speak to a profound rot in American governance, the military industrial complex, and American business regulation more generally,

Often times the conclusions drawn are dangerously delusional: A draft would be more likely to break the American nation than save it. As indeed conscription has resulted in Ukraine’s population collapsing with somewhere between 6 and 10 million Ukrainians (out of a pre-war 36 million) having fled the country, not to escape the mostly static war, but to escape the Totalitarian conditions the Zelensky regime has imposed in response to the war. (1.1 million of whom escaped INTO Russia, for any who deny this [is] largely an ethnic conflict between Western and Russian Ukrainians, as it has been since 2014).

And the thing is all of these discussions rest on a assumption that seems ludicrous the second you stop and think about it: Ukraine is not the future of Warfare, these conditions will be almost impossible to ever create again.

Ukraine had a pre-war Nominal GDP of 199 billion USD. Officially this only declined to 160 billion in 2022 as a result of the war, but there’s good reason to think its actual internal private sector economy collapsed far further [given] it had collapsed from 177 billion in 2013 to 90 billion in 2015 as a result of the US backed Coup/Revolution.

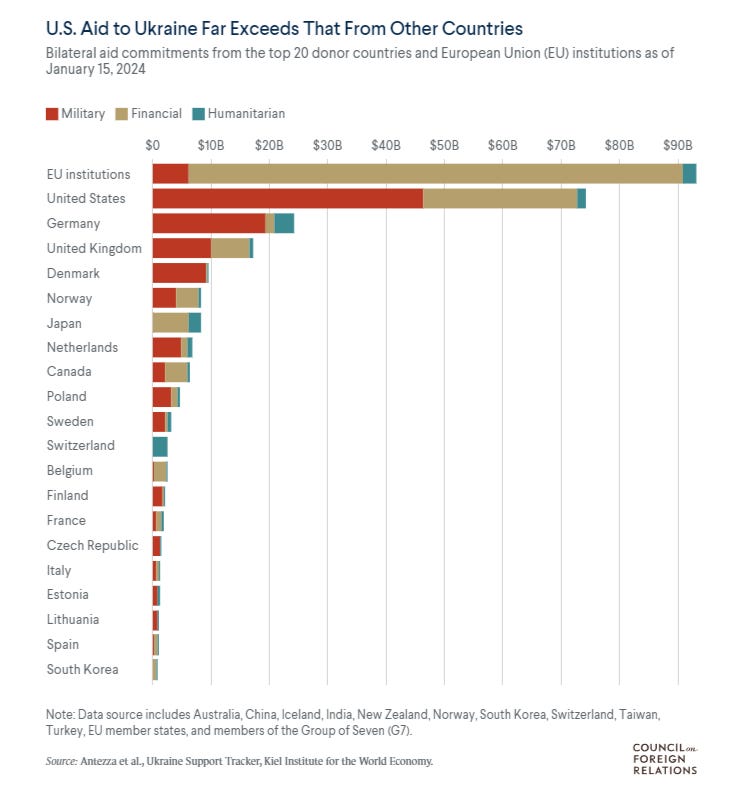

Indeed given the population flight, conscription, and impositions on the populace, it is very likely a SUPER-MAJORITY of that 160 billion GDP in 2022, was actually the result of US and NATO pouring hundreds of billions into the country. Where it was either used or siphoned off as corruption.

Simply put Ukraine has received military, financial and other aid most like in excess of what its entire internal economy produced in the same period, and as of writing it’s still losing territory.

When commentators say this is a war between NATO and Russia they are almost entirely correct. If you combine all the economies that are funding, arming, or fighting on one side or the other of this war you get a majority of the entire global economy.

And they have used all that money to pay off the Ukrainian regime to refuse any peace agreement, even ones their own negotiators had agreed to, and that were clearly in the best interest of the country … you know if you value hundreds of thousands of young men and not having your population collapse more than narrow stretches of land being bought up by Blackrock.

April 29, 2024

QotD: The draft

What frightened me was not going to Vietnam. What frightened me was going in the Army. The haircut, the uniform, the discipline: If I’d been allowed to go to Vietnam in my old clothes … The minute the draft disappeared, the whole hippie-dippy thing just went up in smoke.

P.J. O’Rourke, interviewed by Scott Walter, “The 60’s Return”, American Enterprise, May/June 1997.

March 27, 2024

Civil Defence is a real thing in Finland

Paul Wells reports back on his recent trip to Finland, where he got to tour one of the big civil-defence shelters in Helsinki:

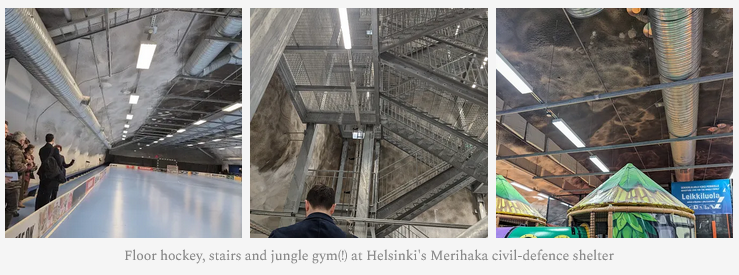

One of the best playgrounds for children in Helsinki is the size of three NFL football fields, dug into bedrock 25 metres below a street-level car park, and built to survive a nuclear bomb.

The air down here is surprisingly fresh. The floor-hockey rinks — there are two, laid end to end — are well maintained. The refreshment stands are stocked with snacks. The steel blast doors are so massive it takes two people to slam one shut.

Finland has been building civil-defence shelters, methodically and without fuss, since the late 1950s. This one under the Merihaka residential district has room for 6,000 people. It’s so impressive that it’s the Finnish capital’s unofficial media shelter, the one visiting reporters are likeliest to be shown. The snack bar and the jungle gym are not for show, however: as a matter of government policy, every shelter must have a second, ordinary-world vocation, to ensure it gets used and, therefore, maintained between crises.

The Merihaka shelter was one of the stops on my visit to Helsinki last week. The first anniversary of Finland’s membership in NATO, the transatlantic defence alliance, is next week, on April 4. Finland’s foreign office invited journalists from several NATO countries to visit Helsinki to update us on Finland’s defence situation. I covered my air travel and hotel. Or rather, paid subscribers to this newsletter did. Your support makes this sort of work possible. I’m always grateful.

The Finnish government used to build most of the shelters. But since 2011, the law has required that new shelters be built at the owners’ expense, by owners of buildings larger than 1,200 square metres and industrial buildings larger than 1,500 square metres.

The city of Helsinki has more shelter space than it has people, including visitors from out of town. Across the country the supply is a little tighter. Altogether today Finland has a total of 50,500 shelters with room for 4.8 million people.

That’s not enough for the 5.5 million people in Finland. But then, if war ever comes, much of the population won’t need shelter, because they’ll be staying groundside to fight.

Conscription is universal for Finnish men between 18 and 60. (Women have been enlisting on a voluntary basis since the 1990s.) The standing armed forces, 24,000, aren’t all that big. But everyone who finishes their compulsory service is in the reserves for decades after, with frequent training to keep up their readiness. In a war the army can surge to 280,000. In a big war, bigger still.

The Soviet Union invaded Finland in 1939, during what was, in most other respects, the “phony war” phase of the Second World War. The Finnish army inflicted perhaps five times as many casualties on the Soviets as they suffered, but the country lost 9% of its territory and has no interest in losing more. Finland’s foreign policy since then has been based on the overriding importance of avoiding a Russian invasion.

March 14, 2024

QotD: Recruiting an army in the Roman Republic

Before we dive in, we should stop to clarify some of our key actors here, the Roman magistrates and officers with a role in all of this. A Roman army consisted of one or more legions, supported by a number (usually two) alae recruited from Rome’s Italian allies, the socii. Legions in the Republic did not have specific commanders, rather the whole army was commanded by a single magistrate with imperium (the power to command armies and organize courts). That magistrate was usually a consul (of which there were two every year), but praetors and dictators,1 all had imperium and so might lead an army. Generally the consuls lead the main two armies. When more commanders were needed, former consuls and praetors might be delegated the job as a stand-in for the current magistrates, these were called pro-consuls and pro-praetors (or collectively, “pro-magistrates”) and they had imperium too.

In addition to the imperium-haver leading the army, there were also a set of staff officers called military tribunes, important to the process. These fellows don’t have command of a specific part of the legion, but are “officers without portfolio”, handling whatever the imperium-haver wants handled; at times they may have command of part of a legion or all of one legion. Finally, there’s one more major magistrate in the army: the quaestor. A much more junior magistrate than the imperium-haver (but senior to the tribunes), he handles pay and probably in this period also supply. That said, the quaestor is not usually the general’s “number two” even though it seems like he might be; quaestors are quite junior magistrates and the imperium-haver has probably brought friends or advisors with a lot more experience than his quaestor (who may or may not be someone the imperium-haver knows or likes). […]

The first thing to note about this process, before we even start is that the dilectus was a regular process which happened every year at a regular time. The Romans did have a system to rapidly raise new troops in an emergency (it was called a tumultus), where the main officials, the consuls, could just grab any citizen into their army in a major emergency. But emergencies like that were very rare; for the most part the Roman army was filled out by the regular process of the dilectus, which happened annually in tune with Rome’s political calendar. That regularity is going to be important to understand how this process is able to move so many people around: because it is regular, people could adapt their schedules and make provisions for a process that happened every year. I should note the dilectus could also be held out of season, though often the times we hear about this it is because it went poorly (e.g. in 275 BC, no one shows up).

The process really begins with the consular elections for the year, which bounced around a little in the calendar but generally happened around September,2 though the consuls do not take office until the start of the next calendar year. As we’ve discussed, the year originally seems to have started in March (and so consuls were inaugurated then), but in 153 was shifted to January (and so consuls were inaugurated then).

What’s really clear is that there is some standard business that happens as the year turns over every year in the Middle Republic and we can see this in the way that Livy structures his history, with year-breaks signaled by these events: the inauguration of new consuls, the assignment of senior Roman magistrates and pro-magistrates to provinces, and the determinations of how forces will be allotted between those provinces. And that sequence makes a lot of sense: once the Senate knows who has been elected, it can assign provinces to them for the coming year (the law requiring Senate province assignments to be blind to who was elected, the lex Sempronia de provinciis consularibus, was only passed in 123) and then allocate troops to them. That allocation (which also, by the by, includes redirecting food supplies from one theater to another, as Rome is often militarily actively in multiple places) includes both existing formations, but is also going to include the raising of new legions or the conscription of new troops to fill out existing legions, a practice Livy notes.

The consuls, now inaugurated have another key task before they can embark on the dilectus, which is the selection of military tribunes, a set of staff officers who assist the consuls and other magistrates leading armies. There are six military tribunes per legion (so 24 in a normal year where each consul enrolls two legions); by this point four are elected and two are appointed by the consul. The military tribunes themselves seem to have often been a mix, some of them being relatively inexperienced aristocrats doing their military service in the most prestigious way possible and getting command experience, while Polybius also notes that some military tribunes were required to have already had a decade in the ranks when selected (Polyb. 6.19.1). These fellows have to be selected first because they clearly matter for the process as it goes forward.

The end of this process, which as we’ll see takes place over several days at least, though exactly how many is unclear, will have have had to have taken place in or before March, the Roman month of Martius, which opened the normal campaigning season with a bunch of festivals on the Kalends (the first day of the month) to Mars. As Rome’s wars grew more distant and its domestic affairs more complex, it’s not surprising that the Romans opted to shift where the year began on the calendar to give the new consuls a bit more of winter to work with before they would be departing Rome with their armies. It should be noted that while Roman warfare was seasonal, it was only weakly so: Roman armies stayed deployed all year round in the Middle Republic, but serious operations generally waited until spring when forage and fodder would be more available.

That in turn also means that the dilectus is taking place in winter, which also matters for understanding the process: this is a low-ebb in the labor demands in the agricultural calendar. I find it striking that Rome’s elections happen in late summer or early fall, when it would actually be rather inconvenient for poor Romans to spend a day voting (it’s the planting season), but the dilectus is placed over winter where it would be far easier to get everyone to show up. I doubt this contrast was accidental; the Roman election system is quite intentionally designed to preference the votes of wealthier Romans in quite a few ways.

So before the dilectus begins, we have our regular sequence: the consuls are inaugurated at the beginning of the year, the Senate meets and assigns provinces and sets military priorities, including how many soldiers are to be enrolled. The Senate’s advice is not technically legally binding, but in this period is almost always obeyed. Military tribunes are selected (some by election, some by appointment) and at last the consuls can announce the day of the dilectus, conveniently now falling in the first couple of months of the year when the demand for agricultural labor is low and thus everyone, in theory, can afford to show up for the selection process.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: How To Raise a Roman Army: The Dilectus“, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2023-06-16.

1. And the dictator’s master of the horse.

2. On this, see J.T. Ramsey, “The Date of the Consular Elections in 63 and the Inception of Catiline’s Conspiracy”, HSCP 110 (2019): 213-270.

January 12, 2024

QotD: Rome’s Italic “allies”

The Roman Republic spent its first two and a half centuries (or so) expanding fitfully through peninsular Italy (that is, Italy south of the Po River Valley, not including Sicily). This isn’t the place for a full discussion of the slow process of expanding Roman control (which wouldn’t be entirely completed until 272 with the surrender of Tarentum). The consensus position on the process is that it was one in which Rome exploited local rivalries to champion one side or the other making an ally of the one by intervening and the other by defeating and subjecting them (this view underlies the excellent M.P. Fronda, Between Rome and Carthage: Southern Italy During the Second Punic War (2010); E.T. Salmon, The Making of Roman Italy (1982) remains a valuable introduction to the topic). More recently, N. Terranato, The Early Roman Expansion into Italy (2019) has argued for something more based on horizontal elite networks and diplomacy, though this remains decidedly a minority opinion (I myself am rather closer to the consensus position, though Terranato has a point about the role of elite negotiation in the process).

The simple (and perhaps now increasingly dated) way I explain this to my students is that Rome follows the Goku Model of Imperialism: I beat you, therefore we are now friends. Defeated communities in Italy (the system is different outside of Italy) are made to join Rome’s alliance network as socii (“allies”), do not have tribute imposed on them, but must supply their soldiers to fight with Rome when Rome is at war, which is always.

It actually doesn’t matter for us how this expansion was accomplished; rather we’re interested in the sort of order the Romans set up when they did expand. The basic blueprint for how Rome interacted with the Italians may have emerged as early as 493 with the Foedus Cassianum, a peace treaty which ended a war between Rome and [the] Latin League (an alliance of ethnically Latin cities in Latium). To simplify quite a lot, the Roman “deal” with the communities of Italy which one by one came under Roman power went as follows:

- All subject communities in Italy became socii (“allies”). This was true if Rome actually intervened to help you as your ally, or if Rome intervened against you and conquered your community.

- The socii retained substantial internal autonomy (they kept their own laws, religions, language and customs), but could have no foreign policy except their alliance with Rome.

- Whenever Rome went to war, the socii were required to send soldiers to assist Rome’s armies; the number of socii in Rome’s armies ranged from around half to perhaps as much as two thirds at some points (though the socii outnumbered the Romans in Italy about 3-to-1 in 225, so the Romans made more strenuous manpower demands on themselves than their allies).

- Rome didn’t impose tribute on the socii, though the socii bore the cost of raising and paying their detachments of troops in war (except for food, which the Romans paid for, Plb. 6.39.14).

- Rome goes to war every year.

- No, seriously. Every. Year. From 509 to 31BC, the only exception was 241-235. That’s it. Six years of peace in 478 years of republic. The socii do not seem to have minded very much; they seem to have generally been as bellicose as the Romans and anyway …

- The spoils of Roman victory were split between Rome and the socii. Consequently, as one scholar memorably put it, the Roman alliance was akin to, “a criminal operation which compensates its victims by enrolling them in the gang and inviting them to share to proceeds of future robberies” (T. Cornell, The Beginnings of Rome (1995)).

- The alliance system included a ladder of potential relationships with Rome which the Romans might offer to loyal allies.

Now this isn’t a place for a long discussion of the Roman alliance system in Italy (that place is in the book I am writing), so I want us to focus more narrowly on the bolded points here and how they add up to significant changes in who counted as “Roman” over time. But I should note here that while I am calling this a Roman “alliance system” (because the Romans call these fellows socii, allies) this was by no means an equal arrangement: Rome declared the wars, commanded the armies and set the quotas for military service. The “allies” were thus allies in name only, but in practice subjects; nevertheless the Roman insistence on calling them allies and retaining the polite fiction that they were junior partners rather than subject communities, by doing things like sharing the loot and glory of victory, was a major contributor to Roman success (as we’ll see).

First, the Roman alliance system was split into what were essentially tiers of status. At the top were Roman citizens optimo iure (“full rights”, literally “with the best right”) often referred to on a community basis as civitas cum suffragio (“citizenship with the vote”). These were folks with the full benefits of Roman citizenship and the innermost core of the Roman polity, who could vote and (in theory, though for people of modest means, only in theory) run for office. Next were citizens non optimo iure, often referred to as having civitas sine suffragio (“citizenship without the vote”); they had all of the rights of Roman citizens except for political participation in Rome. This was almost always because they lived in communities well outside the city of Rome with their own local government (where they could vote); we’ll talk about how you get those communities in a second. That said, citizens without the vote still had the right to hold property in Roman territory and conduct business with the full protection of a Roman citizen (ius commercii) and the right to contract legal marriages with Roman citizens (ius conubii). They could do everything except for vote or run for offices in Rome itself.

Next down on the list were socii (allies) of Latin status (note this is a legal status and is entirely disconnected from Latin ethnicity; by the end of this post, Rome is going to be block-granting Latin status to Gauls in Cisalpine Gaul, for instance). Allies of Latin status got the benefits of the ius commercii, as well as the ability to move from one community with Latin status to another without losing their status. Unlike the citizens without the vote, they didn’t automatically get the right to contract legal marriages with Roman citizens, but in some cases the Romans granted that right to either individuals or entire communities (scholars differ on exactly how frequently those with Latin status would have conubium with Roman citizens; the traditional view is that this was a standard perk of Latin status, but see Roselaar, op. cit.). That said, the advantages of this status were considerable – particularly the ability to conduct business under Roman law rather than what the Romans called the “ius gentium” (“law of peoples”) which governed relations with foreigners (peregrini in Roman legal terms) and were less favorable (although free foreigners in Rome had somewhat better protections, on the whole, than free foreigners – like metics – in a Greek polis).

Finally, you had the socii who lacked these bells and whistles. That said, because their communities were allies of Rome in Italy (this system is not exported overseas), they were immune to tribute, Roman magistrates couldn’t make war on them and Roman armies would protect them in war – so they were still better off than a community that was purely of peregrini (or a community within one of Rome’s provinces; Italy was not a province, to be clear).

The key to this system is that socii who stayed loyal to Rome and dutifully supplied troops could be “upgraded” for their service, though in at least some cases, we know that socii opted not to accept Roman citizenship but instead chose to keep their status as their own community (the famous example of this were the allied soldiers of Praenesti, who refused Roman citizenship in 211, Liv. 23.20.2). Consequently, whole communities might inch closer to becoming Romans as a consequence of long service as Rome’s “allies” (most of whom, we must stress, were at one point or another, Rome’s Italian enemies who had been defeated and incorporated into Rome’s Italian alliance system).

But I mentioned spoils and everyone loves loot. When Rome beat you, in the moment after you lost, but before the Goku Model of Imperialism kicked in and you became friends, the Romans took your stuff. This might mean they very literally sacked your town and carried off objects of value, but it also – and for us more importantly – meant that the Romans seized land. That land would be added to the ager Romanus (the body of land in Italy held by Rome directly rather than belonging to one of Rome’s allies). But of course that land might be very far away from Rome which posed a problem – Rome was, after all, effectively a city-state; the whole point of having the socii-system is that Rome lacked both the means and the desire to directly govern far away communities. But the Romans didn’t want this land to stay vacant – they need the land to be full of farmers liable for conscription into Rome’s armies (there was a minimum property requirement for military service because you needed to be able to buy your own weapons so they had to be freeholding farmers, not enslaved workers). By the by, you can actually understand most of Rome’s decisions inside Italy if you just assume that the main objective of Roman aristocrats is to get bigger armies so they can win bigger battles and so burnish their political credentials back in Rome – that, and not general altruism (of which the Romans had fairly little), was the reason for Rome’s relatively generous alliance system.

The solution was for Rome to essentially plant little Mini-Me versions of itself on that newly taken land. This had some major advantages: first, it put farmers on that land who would be liable for conscription (typically placing them in carefully measured farming plots through a process known as centuriation), either as socii or as Roman citizens (typically without the vote). Second, it planted a loyal community in recently conquered territory which could act as a position of Roman control; notably, no Latin colony of this sort rebelled against Rome during the Second Punic War when Hannibal tried to get as many of the socii to cast off the Romans as he could.

What is important for what we are doing here is to note that the socii seem to have been permitted to contribute to the initial groups settling in these colonies and that these colonies were much more tightly tied to Rome, often having conubium – that right of intermarriage again – with Roman citizens. The consequence of this is that, by the late third century (when Rome is going to fight Carthage) the ager Romanus – the territory of Rome itself – comprises a big chunk of central Italy […] but the people who lived there as Roman citizens (with and without the vote) were not simply descendants of that initial Roman citizen body, but also a mix of people descended from communities of socii throughout Italy.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: The Queen’s Latin or Who Were the Romans, Part II: Citizens and Allies”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2021-06-25.

May 30, 2023

Ban all the words!

Chris Bray reflects on the historical context of literature bans:

Before the Civil War, Southern states banned abolitionist literature. That ban meant that postmasters (illegally!) searched the mail, seized anti-slavery tracts, and burned them. And it meant that people caught with abolitionist pamphlets faced the likelihood of arrest. The District of Columbia considered a ban, then didn’t pass the thing, but Reuben Crandall was still arrested and tried for seditious libel in 1833 when he was caught with abolitionist literature. He was acquitted, then died of illness from a brutal pre-trial detention. Seizure, destruction, arrest: abolitionist literature was banned.

The Soviet writer Yevgeny Zamyatin wrote a 1924 novel, We, depicting a world in which an all-powerful government minutely controlled every aspect of life for an enervated population, finding as an endpoint for their ideological project a surgery that destroyed the centers of the brain that allowed ordinary people to have will and imagination. The Soviet government banned Zamyatin’s work: They seized and destroyed all known copies, told editors and publishers the author was no longer to allowed to publish, and sent Zamyatin into exile, where he died without ever seeing his own country again. Seizure, destruction, exile: Yevgeny Zamyatin’s work was banned.

During World War I, the federal government banned literature that discouraged military service, including tracts that criticized conscription. Subsequently, “socialists Charles Schenck and Elizabeth Baer distributed leaflets declaring that the draft violated the Thirteenth Amendment prohibition against involuntary servitude”. They were arrested, convicted, and imprisoned. The Supreme Court upheld the conviction. Anti-conscription literature was banned: It was seized and destroyed, and people caught distributing it were sent to prison.

In 2023, the tedious midwit poet Amanda Gorman posted on Twitter that she was “gutted” — the standard emotion for tedious midwits — to discover that one of her poems had been “banned” by a school in Florida. The news media raced to proclaim that Florida schools are banning books, the leading edge of the Ron DeSantis fascist wave.

As others have already said, Gorman’s boring poem was moved from an elementary school library shelf to a middle school library shelf, without leaving the library

May 13, 2023

What was the First Modern War?

Real Time History

Published 12 May 2023The question about the first modern war has caused lively debates among historians and YouTube comment sections alike. In this video we take a look at a few candidates and some arguments why they are or aren’t modern wars.

(more…)

March 12, 2023

The young British officer’s attitude toward his men

Dr. Robert Lyman has been working on pulling together various newspaper and magazine articles written by Field Marshal William Slim before the Second World War, to be published later this year. I believe this will include everything he included (in shorter form in some cases) in his 1959 book Unofficial History plus many others. In this excerpt from “Private Richard Chuck, aka The Incorrigible Rogue”, Slim recounts taking command of a company of recent conscripts while recuperating from wounds received earlier in WW1:

“Light duty of a clerical nature,” announced the President of the Medical Board. Not too bad, I thought, as I struggled back into my shirt. “Light duty of a clerical nature” had a nice leisurely sound about it. I remembered a visit I had paid to a friend in one of the new government departments that were springing up all over London at the end of 1915. He had sat at a large desk dictating letters to an attractive young lady. When she got tired of taking down letters, she poured out tea for us. She did it very charmingly. Decidedly, light duty of a clerical nature might prove an agreeable change after a hectic year as a platoon commander and a rather grim six months in hospital. Alas, after a month in charge of the officers’ mess accounts of a reserve battalion, with no more assistant than an adenoidal “C” Class clerk, I had revised my opinion. My one idea was to escape from “light duty of a clerical nature” into something more active. Reserve battalions were like those reservoirs that haunted the arithmetic of our youth — the sort that were filled by two streams and emptied by one. Flowing in came the recovered men from hospitals and convalescent homes and the new enlistments; out went the drafts to battalions overseas. When the stream of voluntary recruits was reduced to a trickle the only way to restore the intake was by conscription, and this was my chance.

It had been decided to segregate the conscripts into a separate company as they arrived. I happened to be the senior subaltern at the moment and I applied for command of the new company. Rather to my surprise, for I was still nominally on light duty, I got it. The conscripts, about a hundred and twenty of them, duly arrived. They looked very much like any other civilians suddenly pushed into uniform, awkward, bewildered, and slightly sheepish, and I regarded them with some misgiving. After all, they were conscripts; I wondered if I should like them.

The young British officer commanding native troops is often asked if he likes his men. An absurd question, for there is only one answer. They are his men. Whether they are jet-black, brown, yellow, or café-au-lait, the young officer will tell you that his particular fellows possess a combination of military virtues denied to any other race. Good soldiers! He is prepared to back them against the Brigade of Guards itself! And not only does the young officer say this, but he most firmly believes it, and that is why, on a thousand battlefields, his men have justified his faith.

In a week I felt like that about my conscripts. I was a certain rise to any remark about one volunteer being worth three pressed men. Slackers? Not a bit of it! They all had good reasons for not joining up. How did I know? I would ask them. And I did. I had them, one by one, into the company office, without even an N.C.O. to see whether military etiquette was observed. They were quite frank. Most of them did have reasons — dependants who would suffer when they went, one-man businesses that would have to shut down. Underlying all the reasons of those who were husbands and fathers was the feeling that the young single men who had escaped into well-paid munitions jobs might have been combed out first.

[…]

We had now advanced far enough in our training to introduce the company to the mysteries of the Mills bomb. There is something about a bomb which is foreign to an Englishman’s nature. Some nations throw bombs as naturally as we kick footballs, but put a bomb into an unschooled Englishman’s hands and all his fingers become thumbs, an ague affects his limbs, and his wits desert him. If he does not fumble the beastly thing and drop it smoking at his — and your — feet, he will probably be so anxious to get rid of it that he will hurl it wildly into the shelter trench where his uneasy comrades cower for safety. It is therefore essential that the recruit should be led gently up to the nerve-racking ordeal of throwing his first live bomb; but as I demonstrated to squad after squad the bomb’s simple mechanism, I grew more and more tired with each until I could no longer resist the temptation to stage a little excitement. I fitted a dummy bomb, containing, of course, neither detonator nor explosive, with a live cap and fuse. Then for the twentieth time I began!

When you pull out the safety-pin you must keep your hand on the lever or it will fly off. If it does it will release the striker, which will hit the cap, which will set the fuse burning. Then in five seconds off goes your bomb. So when you pull out the pin don’t hold the bomb like this!’

I lifted my dummy, jerked out the pin, and let the lever fly off. There was a hiss, and a thin trail of smoke quavered upwards. For a second, until they realized its meaning, the squad blankly watched that tell-tale smoke. Then in a wild sauve qui peut they scattered, some into a nearby trench, others, too panic-stricken to remember this refuge, madly across country, I looked round, childishly pleased at my little joke, to find one figure still stolidly planted before me. Private Chuck alone held his ground, placidly regarding me, the smoking bomb, and his fleeing companions with equal nonchalance. This Casablanca act was, I felt, the final proof of mental deficiency — and yet the small eyes that for a moment met mine were perfectly sane and not a little amused.

“Well,” I said, rather piqued, “hy don’t you run with the others?” A slow grin passed over Chuck’s broad face.

“I reckon if it ‘ud been a real bomb you’d ‘ave got rid of it fast enough,” he said. Light dawned on me.

“After this, Chuck,” I answered, “you can give up pretending to be a fool; you won’t get your discharge that way!”

He looked at me rather startled, and then began to laugh. He laughed quietly, but his great shoulders shook, and when the squad came creeping back they found us both laughing. They found, too, although they may not have realized it at first, a new Chuck; not by any means the sergeant-major’s dream of a soldier, but one who accepted philosophically the irksome restrictions of army life and who even did a little more than the legal minimum.

September 29, 2022

Considering weird possible scenarios in Ukraine

In The Line, Matt Gurney walks through some until recently unimaginable outcomes of the Russian invasion of Ukraine:

It’s probably time for us to start thinking through some weird possible scenarios for what’s happening in Russia. Because the spectrum of what could happen is a lot broader than it seemed only six months ago.

But let’s start with an important exercise in accountability. In previous commentary, I predicted a lot of things well: that Ukrainian resistance would be very effective, that Russia would have major logistics problems, that the Russians would use mass artillery fire against civilians in place of military advances. I was quick to grasp that Ukraine was overperforming and that Russia was struggling early in the conflict.

But getting some details right didn’t help me avoid blowing the conclusion: I thought Russia would win. Not a total victory, but I thought Russia would seize a lot more of the country before its logistical problems and Ukrainian resistance brought their offensives to a halt, leaving Ukraine with some kind of rump state in the west. I certainly didn’t believe in February that Russia could lose, and I never would have believed that Ukraine could actually win on the battlefield, as it now seems more than capable of doing.

I don’t know if I underestimated Ukrainian capabilities, per se. I always expected them to fight bravely and well, and understood the lethality of modern man-portable weapons against tanks and armoured vehicles. It’s probably closer to the mark to say that I overestimated Russia’s capabilities — I was a cynic on their military and expected it to perform badly, but it’s somehow fallen well short of my already low expectations. It is absolutely delightful to be wrong on this one, but readers deserve the truth: I expected Russia’s military to perform better and grab a much bigger chunk of Ukraine before having to stop in the face of logistical dysfunction and Ukrainian resistance. Part of me wonders if the Russians themselves are surprised by how hollowed out their military had become.

With that on the record, let’s flash forward to the present. As noted above, Ukraine now seems fully able to win the war. As I write this, Ukrainian forces are on the move again in the northeast, and seem to be encircling Russian positions in occupied Lyman. If able to complete this latest manoeuvre, Ukrainian forces will cut off a large force of Russian troops and will also seize control of an important local rail junction, threatening Russian logistics (such as they are) in the surrounding area. Perhaps more importantly to the overall conduct of the war, Russia’s effort to mobilize 300,000 men for the war is running into obvious challenges. Men of military age are fleeing the country. Reports from Russia reveal that the army has little in the way of equipment and weapons for the new draftees, and no system in place to train them. There have been comically bizarre stories of infirm old men getting call-up notices, and of draftees being sent to the front after only a day or two of training … at best.

This isn’t a solution to Putin’s problems. It’s a new problem being created in real time. Even if Putin can find 300,000 men, it seems unlikely he can equip them, and even less likely that he can train them. Whether or not he can transport what men he does round up into the battle area is an open question, as is whether or not he can supply them once they get there.

This is the long way of saying something I’ll now just state bluntly: Russia is losing. Putin’s latest actions reveal that he knows he’s losing. If the mobilization flops, as seems likely, he’ll be losing even worse than he was losing before, and he’ll have damn few options to turn that around.

And this is why we need to start thinking through some weird scenarios.

September 17, 2022

In the wake of the Russo-Ukrainian war, Europe’s cold winter looms ahead

Andrew Sullivan allows his views on the fighting in Ukraine to be a bit more optimistic after Ukrainian gains in the most recent counter-attacks on Russian-held territory around Kharkiv:

Approximate front-line positions just before the Ukrainian counter-attack east of Kharkiv in early September 2022. The MOD appears to have stopped posting these daily map updates sometime in the last month or so (this is the most recent as of Friday afternoon).

As we were going to press last week — I still don’t know a better web-era phrase for that process — Ukraine mounted its long-awaited initiative to break the military stalemate that had set in after Russia’s initial defeat in attempting a full-scale invasion. The Kharkiv advance was far more successful than anyone seems to have expected, including the Ukrainians. You’ve seen the maps of regained territory, but the psychological impact is surely more profound. Russian morale is in the toilet — and if it seems a bit premature to say that Ukraine will soon “win” the war, it’s harder and harder to see how Russia doesn’t lose it. By any measure, this is a wonderful development — made possible by Ukrainian courage and Western arms.

Does this change my gloomy assessment of Putin’s economic war on Europe, which will gain momentum as the winter drags on? Yes and no. Yes, it will help shore up nervous European governments who can now point to Ukraine’s success to justify the coming energy-driven recession. No, it will not make that recession any less intense or destabilizing. It may make it worse, as Putin lashes out.

More to the point, the Kharkiv euphoria will not last forever. September is not next February. Russia still has plenty of ammunition to throw Ukraine’s way (even if it has to scrounge some from North Korea); it is still occupying close to a fifth of the country; still enjoying record oil revenues; has yet to fully mobilize for a war; and still has China and much of the developing world in (very tepid) acquiescence. Putin is very much at bay. But he is not finished.

Europe’s scramble to prevent mass suffering this winter is made up of beefing up reserves (now 84 percent full, ahead of schedule), energy rationing, government pledges to cut gas and electricity use, nationalization of gas companies, and billions in aid to consumers and industry, with some of the money recouped by windfall taxes on energy suppliers. The record recently is cause for optimism:

The Swedish energy company Vattenfall AB said industrial demand for gas in France, the U.K., the Netherlands, Belgium and Italy is down about 15% annually.

But the use of gas by households is trivial in the summer in Europe compared with the winter — and subsidizing the cost doesn’t help conservation. Russia will now cut off all gas — which could send an economy like Italy’s to contract more than 5 percent in one year. There really is no way out of imminent, deep economic distress across the continent. Even countries with minimal dependence on Russia, like Britain, are locked into an energy market with soaring costs.

That will, in turn, strengthen some of the populist-right parties — see Italy and Sweden. The good news is that the new right in Sweden backs NATO, and Italy’s post-liberal darling, Georgia Meloni, who once stanned Putin, “now calls [him] an anti-Western aggressor and said she would ‘totally’ continue to send offensive arms to Ukraine”. The growing evidence of the Russian army’s war crimes — another mass grave was just discovered in Izyum — makes appeasement ever more morally repellent.

So what will Putin do now? That is the question. His military is incapable of recapturing lost territory anytime soon; he is desperate for allies; and mobilizing the entire country carries huge political risks. It’s striking to me that in a new piece, Aleksandr Dugin, the Russian right’s guru, is both apoplectic about the war’s direction and yet still rules out mass conscription:

Mobilization is inevitable. War affects everyone and everything, but mobilization does not mean forcibly sending conscripts to the front, this can be avoided, for example, by forming a fully-fledged volunteer movement, with the necessary benefits and state support. We must focus on veterans and special support for the Novorossian warriors.

This is weak sauce — especially given Dugin’s view that the West is bent on “a war of annihilation against us — the third world war”. It’s that scenario that could lead to a real and potentially catastrophic escalation — which may be why the German Chancellor remains leery of sending more tanks to Ukraine. The danger is a desperate Putin doing something, well, desperate.

I have no particular insight into intra-Russian arguments over mobilization, but there seems to be zero point (other than for propaganda … and that cuts both ways) to instituting a “Great Patriotic War”-style mass conscription drive at this point. The Russian army could absolutely be boosted to vast numbers through conscription. Vast numbers of untrained, unwilling young people with little military training and no particular passion to save the Rodina this time, despite constant regime callbacks to desperate struggle against Hitler in 1941-45. Pushing under- or untrained troops into battle against a Ukrainian army equipped with relatively modern western weaponry would be little more than deliberate slaughter and I can’t believe even Putin would be that reckless.

June 6, 2022

“I ask, sir, what is the militia? It is the whole people except for a few public officials”

George Mason, quoted in the title of this post, had a very expansive view of the US militia. Most Americans of the day did not seem to share this view, as Chris Bray explains:

How Congress may have visualized the individual minutemen who would compose the militia of the United States after 1792.

Postcard image of French’s Concord Minuteman statue via Wikimedia Commons.

In the second Militia Act of 1792, Congress defined a uniform militia in all of the states:

That each and every free able-bodied white male citizen of the respective States, resident therein, who is or shall be of age of eighteen years, and under the age of forty-five years (except as is herein after excepted) shall severally and respectively be enrolled in the militia … That every citizen, so enrolled and notified, shall, within six months thereafter, provide himself with a good musket or firelock, a sufficient bayonet and belt, two spare flints, and a knapsack, a pouch, with a box therein, to contain not less than twenty four cartridges, suited to the bore of his musket or firelock, each cartridge to contain a proper quantity of powder and ball … and shall appear so armed, accoutred and provided, when called out to exercise or into service, except, that when called out on company days to exercise only, he may appear without a knapsack.

So, by federal law, every military-age white male in the country (except men who were exempted by the states, like clergymen) had to report to the local militia commander to be enrolled in their local company, and had to own a long list of equipment, and had to show up to train with that equipment when ordered.

They mostly didn’t. For decades, states reported their militia enrollment to the War Department, and it sometimes appeared that some states, by trying really hard, sometimes almost made it to something in the neighborhood of half participation. In 1826, the Barbour Board — named after Secretary of War James Barbour — evaluated the unmistakable failure of the federally defined uniform militia, and suggested trying again with a smaller group of select militiamen. The board’s report was universally ignored, because by 1826 the federal government, like, couldn’t even: Everyone knew the model of widely shared militia service had failed.

Historians have usually described the failure of universal white male militia service in the early republic as a top-down policy blunder in which political leaders didn’t try hard enough to make the thing work. But a marginal historian named Chris Bray, in a dissertation that generated no excitement of any kind in academia, argued that the universal white male militia obligation was doomed by something else: widespread irritation and popular resistance. The militia obligation reached into the lives of militiamen in ways they didn’t expect and wouldn’t tolerate, so they stopped showing up.

There are many different ways to tell this story, but let’s do it quickly.