Forgotten Weapons

Published 24 May 2023Lots of people put together significant gun collections over a lifetime, and want to see those collections preserved after they pass. This often manifests as looking for a museum that will keep a collection intact and display it — which is unfortunately a nearly impossible goal.

First, it is very rare to find a museum whose mission matches the collection focus of a specific private collection. Firearms cover a vast amount of history even firearms-specific museums are usually fairly narrow in scope.

Second, museums already have all their display space filled. Promising to display a new collection means taking down something they already deemed worthy of display — and promising not to take it down in turn if something more suitable comes along.

Third, even if a museum has space and shares the theme of a collection, they will almost certainly already have examples of many of the items in the collection. If a museum is not allowed to break up and sell off parts of a collection, it simply ensures that many of the items will remain perpetually locked away in a reserve archive.

I would propose that we really need to rethink the idea that museums have a duty to keep everything they acquire. We know that virtually all museums have much more in storage than on display, and forcing duplicate items or pieces unrelated to the museum’s focus to remain in museum property simply ensures that those pieces are kept away from the collecting community. It is the collecting community that does most of the research and publication on firearms history, and this practice undoubtedly hinders research and scholarship. That is not to say we should close museums; certainly not! Museums are extremely valuable for preserving artifacts and making them available to some degree to the public, but they are only one part of the historical community.

If you are a collector who really wants your collection to be displayed in full in a museum, you really only have one option: bequeath the museum enough money to build and maintain a new wing specifically for your collection.

(more…)

September 4, 2023

Ask Ian: Donating Gun Collections to Museums … or Not

September 3, 2023

The War is Five Years Old – WW2 – Week 262 – September 2, 1944

World War Two

Published 2 Sep 2023Five years of war and no real end in sight, though the Allies sure seem to have the upper hand at the moment. Romania is coming under the Soviet thumb and Red Army troops are at Bulgaria’s borders, the Allies enter Belgium and also take ports in the south of France. A Slovak National Uprising begins against the Germans, and the Warsaw Uprising against them continues, but in China it is plans for defense being made against the advancing Japanese.

(more…)

September 2, 2023

Trial Run for D-Day – Allied Invasion of Sicily 1943

Real Time History

Published 1 Sept 2023After defeating the Axis in North Africa, the stage was set for the first Allied landing in Europe. The target was Sicily and in summer 1943 Allied generals Patton and Montgomery set their sights on the island off the Italian peninsula.

(more…)

September 1, 2023

How the term “the Deep State” morphed from left-wing to (extreme, scary, ultra-MAGA) right-wing jargon

Matt Taibbi wants to track the changes in political language in US usage, starting today with “Deep State”:

In July of last year David Rothkopf wrote a piece for the Daily Beast called, “You’re going to miss the Deep State when it’s gone: Trump’s terrifying plan to purge tens of thousands of career government workers and replace them with loyal stooges must be stopped in its tracks.” In the obligatory MSNBC segment hyping the article, poor Willie Geist, fast becoming the Zelig of cable’s historical lowlight reel, read off the money passage:

During his presidency, [Donald] Trump was regularly frustrated that government employees — appointees, as well as career officials in the civil service, the military, the intelligence community, and the foreign service — were an impediment to the autocratic impulses about which he often openly fantasized.

This passage portraying harmless “government employees” as the last patriotic impediment to Trumpian autocracy represented the complete turnaround of a term that less than ten years before meant, to the Beast‘s own target audience, the polar opposite. This of course needed to be lied about as well, and the Beast columnist stuck this landing, too, when Geist led Rothkopf through the eye-rolling proposition that there was “something fishy, or dark, or something going on behind the scenes” with the “deep state”.

Rothkopf replied that “career government officials” got a bad rap because “about ten years ago, Alex Jones and the InfoWars crowd started zeroing in on the deep state, as yet another of the conspiracy theories …”

The real provenance of deep state has in ten short years been fully excised from mainstream conversation, in the best and most thorough whitewash job since the Soviets wiped the photo record clean of Yezhov and Trotsky. It’s an awesome achievement.

Through the turn of the 21st century virtually no American political writers used deep state. In the mid-2000s, as laws like the PATRIOT Act passed and the Bush/Cheney government funded huge new agencies like the Department of Homeland Security, the word was suddenly everywhere, inevitably deployed as left-of-center critique of the Bush-Cheney legacy.

How different was the world ten years ago? The New York Times featured a breezy Sunday opinion piece asking the late NSA whistleblower Thomas Drake — a man described as an inspiration for Edward Snowden who today would almost certainly be denounced as a traitor — what he was reading then. Drake answered he was reading Deep State: Inside the Government Secrecy Industry by Marc Ambinder, whose revelations about possible spying on “eighteen locations in the Washington D.C. area, including near the White House, Congress, and several foreign embassies”, inspired the ACLU to urge congress to begin encrypting communications.

On the eve of a series of brutal revelations about intelligence abuses, including the Snowden mess, left-leaning American commentators all over embraced “deep state” as a term perfectly descriptive of the threat they perceived from the hyper-concentrated, unelected power observed with horror in the Bush years. None other than liberal icon Bill Moyers convinced Mike Lofgren — a onetime Republican operative who flipped on his formers and became heavily critical of the GOP during this period — to compose a report called “The Deep State Hiding in Plain Sight“.

Nylon 66: Remington’s Revolutionary Plastic Rifle

Forgotten Weapons

Published 19 May 2023In the 1950s, Remington decided that it needed an inexpensive new .22 self-loading rifle to add to its catalog. In looking at how to reduce the cost of such a rifle, they hit upon the idea of using polymer to replace the wooden furniture typically used — and to replace the metal receiver as well. Remington was owned by DuPont at the time, and DuPont had developed an excellent strong polymer which they called “Nylon” — specifically, Nylon composition number 66.

Remington engineers developed a massively complex and expensive mold to inexpensively stamp out monolithic polymer .22 rifles in the mid 1950s. They knew this design would cause concern to a large part of their market because of its non-traditional construction, and so they put the new rifles through hundreds of thousands of rounds of grueling testing. It passed these trials with flying colors, and was released in January 1959 to pretty rave reviews. By the time it was finally taken out of production in 1987, more than 1,050,000 of them had been produced — a fantastic success on a pretty big gamble.

Thanks to Dutch Hillenburg for loan of this example to show you!

(more…)

QotD: Process thinking about the Russo-Ukraine war

Process thinking has goals, of course, but they’re all interpersonal. The outcomes, small-o, of Process thinking all have to do with relationships within the group. Why are there blacks in ads for camping gear, despite no black person ever having gone camping in the history of the human race? Because the set designer assumes the writer wants it, and the writer assumes that the creative director wants it, and the creative director assumes the client wants it … which he does, but only because he in turn assumes that the creative director wants it, and etc. To return it to politics, it’s all Narrative.

Combining them, consider the Ukraine Narrative as one giant ad campaign. The lack of Outcome-thinking hit all of us from the very moment it became The Current Thing. What, exactly, are we doing in Ukraine?

Note that there is a case to be made. I don’t agree with it, obviously, but I can make one, and of course it’s ruthlessly Outcome-driven: In a world where States have no friends, only interests, it is consistent with Realpolitik to weaken your rivals when it can be done at low cost and minimal risk. We’re doing to Russia what Russia (and China) did to us in Vietnam — they were quite open about aiding their fraternal socialist brothers in the struggle against Capitalism and Western Imperialism.

One can — and of course in this case would — argue that fucking around in Ukraine is neither low-cost nor low-risk, but that too is Outcome-thinking. You can persuade me, an Outcome thinker, with facts and reason. Steve Sailer is almost a caricature of an Outcome thinker at this point, and he’d be just super at demolishing my hypothetical Realpolitik argument for US aid to Ukraine.

But not only do the Process-“thinkers” in [Washington, DC] not have an Outcome in mind, it never crossed their minds to have one in the first place. This is why I keep coming back to Jaynes [Wiki]. We — normal people — keep trying to assign goals to people like Victoria Nuland. The only goals we can come up with, though, are bugfuck insane — she seems to really believe that not only can Ukraine win the current conflict, but that they’ll march all the way to Moscow, Regime-Change everyone, and invite all the Western parasites in to carve up the country …

… nothing else makes sense, but “sense” left the building with Elvis. There is no Outcome. Which is likelier:

- that she has some top secret Master Plan in a manila folder in a safe somewhere, that reads “Ukraine captures Moscow; Exxon CEO is on the first flight in”; or

- Her behavior seems purposive the way the eerily coordinated gyrations of a school of fish or a flock of birds seems purposive? It looks coordinated, but it can’t actually BE coordinated — it happens too fast for all the individual members to process the signals.

I’ve done a lot of Ukraine shit in the stoyak roundups, and I have never once seen a Victory scenario. The closest even the wildest-eyed optimist comes is very clearly Underpants Gnome shit:

- Send Wunderwaffen to Zelensky

- ???

- Victory!!!

And the third term — the crucial one, Victory — is never ever defined. Let’s assume the Wunderwaffen work and the Big Spring Counteroffensive that they’ve almost literally been advertising, Mad Men-style, goes off flawlessly. What then? At what point do we call off the dogs? Again, unless you seriously believe in Victoria Nuland’s Master Plan — a real document in a real safe, that she got Brandon’s puppeteers to forge his signature on — there simply IS no answer. Their “plan” for “victory” on the battlefield is exactly the same as Bud Light’s “plan” for “victory” with the [Dylan Mulvaney] ads.

It’s all Narrative, all Process. The only outcomes anyone involved considers are all small-o, and they’re all interpersonal. Nobody thinks about battlefield victory — the actual movement of lines on a map, let alone the reality of fighting and dying. But they obsess over being seen to believe in victory. To return to Geo. Orwell‘s commentary:

Creatives spend perhaps half their time in protracted meetings where the primary activity is herding cats, making sure everyone agrees on the current direction of things … until the direction changes, a couple of hours later.

And everyone is fine with this, because everything of importance happens interpersonally.

I’m going to reuse this quote, but this time quote it in full. Two paragraphs, and they’re long, but extremely important. Here’s the first:

The art directors and copywriters who dream up what you see in commercials tend to have a few things in common. The copywriters imagine themselves future screenwriters or novelists, the art directors imagine themselves movie directors eventually. For them, every commercial is a little self-contained movie with a plot and characters, even though no one in the real world gives fifty milliseconds of thought to the character of the TV housewife using that new dustbuster. They very seldom discuss sales, in the sense of “Will this sell more widgets?” In fact they mostly loathe “hard sell” advertising, where you emphasize price.

Emphasis mine, because the question “Will this sell more widgets?” is the definition of Outcome thinking. And if you’re trying to herd cats — as anyone who has had to endure this kind of meeting knows — measurable results are the enemy. Because I really want you to consider the answer to the following question: What’s in it for you, personally, if Acme Corp. sells a thousand more widgets?

Unless you’re a salesman on commission, the answer, for all practical purposes, is: Nothing. Maybe a small bump in your end-of-year bonus, if you get a year-end bonus, but that’s the absolute best case scenario: Another hundred bucks on a single paycheck, six months down the line.

And while I’m certainly not going to sneeze at a hundred dollars, consider what that Benjamin cost you. Half the office hates you now, because you were right. You’re smarter than them, you bastard, and now they know it. You showed them up. Oh, and you’ve also alienated the other half of the office, because what should have been a thirty minute meeting stretched for two hours because you stuck to your guns. Thanks, asshole, I got caught in rush hour and didn’t get home until 7:30. I hope you choke on your $100 bonus. (And don’t think you’re going to get any love from the people who agreed with you in the meeting from the get-go, because they’re all jealous they didn’t think of it themselves).

Now consider the second paragraph, that gets to the heart of Process thinking:

They [“creatives”] favor “conceptual” advertising, where instead of telling you why this cellphone is superior to another, they show you an ironic or cute story involving the cellphone, or maybe you merely show exciting, vibrant people dancing with the thing, with bright colors and music video tropes. This goes back to the recent discussion here of cultural conformity and “mood boards”. Mood boards have been a very big thing in advertising, even more so than twenty years ago. “Look and feel” takes precedence over most things, especially in corporate, nationwide campaigns. For example, you will see Lexus nationwide commercials where the car drives heroically through some surreal industrial or desert landscape, with extreme lighting and lots of flashy cinematography. Local dealer ads for Lexus will concentrate on terms and pricing, and art directors hate doing local dealer car ads. Not artsy enough.

“Conceptual” ads are collaborative ads. With Outcomes, you’re either right or wrong; it either sells more widgets or it doesn’t, but everyone contributes to “mood”. No one can be proven right via sales figures, but no one can be proven wrong, either. Jane sucks at Outcome-driven advertising, because none of her ads moved the sales needle. But Jane is great at “mood boards”; Jane’s a real team player; Jane makes everyone in the meeting feel special. When Jane runs the meeting, we achieve consensus in thirty minutes. When you run the meeting, Mr. Will This Sell More Widgets, it goes on for hours, and we never get the answer — IF we get the answer — until the next quarter’s sales figures come in.

Apply that to the Ukraine Narrative, and test it against Nehushtan‘s heuristics:

“We have always been at war with Eurasia”: what you have to support turns on a dime and doesn’t have to be consistent with anything that went before.

Check. What you “believe” changes as the “mood board” changes, and the “mood board” changes as the group consensus changes in the pitch meeting. We’re all susceptible to this to some degree — someone with stronger Google-fu than mine can no doubt find that old psych experiment from the Fifties, with something like Müller-Lyer lines. No doubt you recall hearing about it: They planted some kids in the crowd who insisted that the shorter lines were really longer, and since these kids were absolutely adamant in their “belief”, eventually most of the class “agreed” that the shorter lines were actually longer.

That’s all consensus stuff, Process stuff. What does it really cost me to say that the shorter line is actually the longer? If it’ll get Jane to finally shut the fuck up, ok. If Jane happens to be really popular, and especially if I think agreeing with her will get me closer to her panties, then the faster I’m going to agree. And if Jane happens to hold my entire career in her hands, and can get me kicked out of the Cloud, to wander the Cursed Earth among the Dirt People …

“Two Minutes Hate”: doesn’t matter who or what the target person is, they are always slotted into the same role, given the same attributes, and the same criticisms are made of them.

Severian, “What is Leftism? (and what to call it?)”, Founding Questions, 2023-05-30.

August 31, 2023

Why New York Destroyed 3 Iconic Landmarks | Architectural Digest

Architectural Digest

Published 6 Apr 2023Michael Wyetzner of Michielli + Wyetzner Architects returns to AD, this time to look at the history and creation of three New York City landmarks that have since been demolished — but are far from forgotten. From the once (and future?) majesty of Penn Station to the New York Herald building and the original 19th-century Madison Square Garden, Michael gives expert insight into these three historic architectural landmarks, why they were laid to ruin, and what came to replace them.

(more…)

August 29, 2023

The noble reasons New Jersey banned self-service gas stations

Of course, by “noble reasons” I mean “corrupt crony capitalist reasons“:

“Model A Ford in front of Gilmore’s historic Shell gas station” by Corvair Owner is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

New Jersey’s law, like Oregon’s, ostensibly stemmed from safety concerns. In 1949, the state passed the Retail Gasoline Dispensing Safety Act and Regulations, a law that was updated in 2016, which cited “fire hazards directly associated with dispensing fuel” as justification for its ban.

If the idea that Americans and filling stations would be bursting into flames without state officials protecting us from pumping gas sounds silly to you, it should. In fact, safety was not the actual reason for New Jersey’s ban (any more than Oregon’s ban was, though the state cited “increased risk of crime and the increased risk of personal injury resulting from slipping on slick surfaces” as justification).

To understand the actual reason states banned filling stations, look to the life of Irving Reingold (1921-2017), a maverick entrepreneur and workaholic who liked to fly his collection of vintage World War II planes in his spare time. Reingold created a gasoline crisis in the Garden State, in the words of New Jersey writer Paul Mulshine, “by doing something gas station owners hated: He lowered prices”.

In the late 1940s, gasoline was selling for about 22 cents a gallon in New Jersey. Reingold figured out a way to undercut the local gasoline station owners who had entered into a “gentlemen’s agreement” to maintain the current price. He’d allow customers to pump gas themselves.

“Reingold decided to offer the consumer a choice by opening up a 24-pump gas station on Route 17 in Hackensack,” writes Mulshine. “He offered gas at 18.9 cents a gallon. The only requirement was that drivers pump it themselves. They didn’t mind. They lined up for blocks.”

Consumers loved this bit of creative destruction introduced by Reingold. His competition was less thrilled. They decided to stop him — by shooting up his gas station. Reingold responded by installing bulletproof glass.

“So the retailers looked for a softer target — the Statehouse,” Mulshine writes. “The Gasoline Retailers Association prevailed upon its pals in the Legislature to push through a bill banning self-serve gas. The pretext was safety …”

The true purpose of New Jersey’s law had nothing to do with safety or “the common good”. It was old-fashioned cronyism, protectionism via the age-old bootleggers and Baptists grift.

Politicians helped the Gasoline Retailers Association drive Reingold out of business. He and consumers are the losers of the story, yet it remains a wonderful case study in public choice theory economics.

The economist James M. Buchanan received a Nobel Prize for his pioneering work that demonstrated a simple idea: Public officials tend to arrive at decisions based on self-interest and incentives, just like everyone else.

The Souls of Black Folk by W.E.B. Du Bois “runs so fantastically counter to the entire ideology of ‘decolonise'”

In Spiked, Brendan O’Neill finds himself surprised at the inclusion of a very unusual book on a list demanded by those pushing for “decolonization” of university curricula:

W.E.B. Du Bois by James E. Purdy, 1907, gelatin silver print, from the National Portrait Gallery which has explicitly released this digital image under the CC0 license.

Wikimedia Commons.

“Decolonise the curriculum” is a movement that wants university courses to focus less on dead white European males and more on writers of colour. Its argument is that black students need texts that speak directly to them. They need books by authors who look like them. They need books about experiences and ideas they can more readily relate to than they can the stuff written about in “high white culture”. Black students must be able to recognise themselves in what they study, we’re told, or else they’ll feel cheated and demeaned.

I was surprised to find that one of the leading decolonise movements, at the University of Edinburgh, was arguing for WEB Du Bois’ 1903 book, The Souls of Black Folk, to be included on the English curriculum. The activists said it was unreasonable to expect black students to engage with so many white authors. They also need to engage with people like Du Bois, in whose work they might “recognise themselves”. I was surprised, not because I think The Souls of Black Folk shouldn’t be on more university courses – absolutely it should. No, it’s because The Souls of Black Folk runs so fantastically counter to the entire ideology of “decolonise”. It made me wonder if these activists have even read it. Du Bois’ book contains some of the finest arguments you will ever read against the idea that high culture is a white thing that others cannot connect with.

One of my favourite passages in the book, from the chapter on what kind of education black men are fit for, touches on this very question. Here Du Bois makes his critique of those in his own time who were arguing that blacks only require basic education and industrial training. He describes his own experience of higher learning, writing:

I sit with Shakespeare and he winces not. Across the colour line I move arm in arm with Balzac and Dumas … From out the caves of evening that swing between the strong-limbed earth and the tracery of the stars, I summon Aristotle and Aurelius and they come all graciously with no scorn or condescension.

That passage, Du Bois’ moving belief that Shakespeare does not wince at him, captures a central thread of his writing: universalism. Du Bois agitates against accommodating to segregation or low expectations, and argues for the rights of “black folk” to assimilate into the spoils of civilisation; to become, as he puts it, “co-workers in the kingdom of culture”. To those in the late 1800s and early 1900s who argued that black people needed a targeted form of culture, one specific to their needs and capacities, Du Bois said: “We daily hear that an education that encourages aspiration, that sets the loftiest of ideals and seeks as an end culture and character rather than breadwinning, is the privilege of white men, and the danger and delusion of black men.”

Du Bois insisted that it is only through assimilation into the “kingdom of culture” that self-knowledge and self-improvement can truly occur. As he wrote: “Wed with Truth, I dwell above the veil.” The veil he’s referring to is the veil of colour, the one that separated blacks from whites in post-slavery America. For Du Bois, that veil was best lifted via assimilation into the American republic’s political universe and its realm of culture.

Du Bois’ critique of the notion that high culture was for white men, and would prove mystifying to black men, has sadly been superseded by an “anti-racism” with an entirely different outlook. Now, the supposedly radical stance is to believe that high culture is disorientating for black people, and possibly even damaging to their self-esteem, and therefore they require something more targeted. In short, they need release from the kingdom of culture. That, in essence, is what the decolonise movement desires: the “liberation” of non-white peoples from the cultural gains of Western civilisation. Behold the crisis of universalist belief.

August 28, 2023

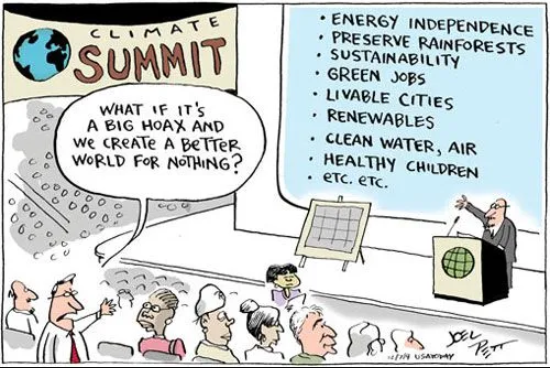

Climate alarmists don’t see costs (to you) as a drawback

David Friedman explains why few if any climate change activists would bother to do a proper cost-benefit analysis of the “solutions” they demand to address climate change:

From the standpoint of an economist, the logic of global warming is straightforward. There are costs to letting it happen, there are costs to preventing it, and by comparing the two we decide what, if anything, ought to be done. But many of the people supporting policies to reduce climate change do not see the question that way. What I see as costs, they see as benefits.

Reduced energy use is a cost if you approve of other people being able to do what they want, which includes choosing to live in the suburbs, drive cars instead of taking mass transit, heat or air condition their homes to what they find a comfortable temperature. It is a benefit if you believe that you know better than other people how they should live their lives, know that a European style inner city with a dense population, local stores, local jobs, mass transit instead of private cars, is a better, more human lifestyle than living in anonymous suburbs, commuting to work, knowing few of your neighbors. It is an attitude that I associate with an old song about little boxes made of ticky-tacky, houses the singer was confident that people shouldn’t be living in, occupied by people whose life style she disapproved of. A very arrogant, and very human, attitude.

There are least three obvious candidates for reducing global warming that do not require a reduction in energy use. One is nuclear power, a well established if currently somewhat expensive technology that produces no CO2 and can be expanded more or less without limit. One is natural gas, which produces considerably less carbon dioxide per unit of power than coal, for which it is the obvious substitute. Fracking has now sharply lowered the price of natural gas with the result that U.S. output of CO2 has fallen. The third and more speculative candidate is geoengineering, one or another of several approaches that have been suggested for cooling earth without reducing CO2 output.

One would expect that someone seriously worried about global warming would take an interest in all three alternatives. In each case there are arguments against as well as arguments for but someone who sees global warming as a serious, perhaps existential, problem ought to be biased in favor, inclined to look for arguments for, not arguments against.

That is not how people who campaign against global warming act. They are less likely than others, not more, to support nuclear power, to approve of fracking as a way of producing lots of cheap natural gas, or to be in favor of experiments to see whether one or another version of geoengineering will work. That makes little sense if they see a reduction in power consumption as a cost, quite a lot if they see it as a benefit.

[…]

The cartoon shown below, which gets posted to Facebook by people arguing for policies to reduce global warming, implies that they are policies they would be in favor of even if warming was not a problem. It apparently does not occur to them that that is a reason for others to distrust their claims about the perils of climate change.

Most would see the point in a commercial context, realize that the fact that someone is trying to sell you a used car is a good reason to be skeptical of his account of what good condition it is in. Most would recognize it in the political context, providing it was not their politics; many believe that criticism of CAGW is largely fueled by the self-interest of oil companies. It apparently does not occur to them that the same argument applies to them, that from the standpoint of the people they want to convince the cartoon is a reason to be more skeptical of their views, not less.1

That is an argument for skepticism of my views as well. Belief in the dangers of climate change provides arguments for policies, large scale government intervention in how people live their lives, that I, as a libertarian, disapprove of, giving me an incentive to believe that climate change is not very dangerous. That is a reason why people who read my writings on the subject should evaluate the arguments and evidence on their merits.

1. One commenter on my blog pointed at a revised version of the cartoon, designed to make the point by offering the same approach in a different context.

The Last Chance | Dorktown

Secret Base

Published 15 Aug 2023The Minnesota Vikings of the 1970s were among the greatest football teams ever assembled. Entering 1974, Bud Grant’s teams had reached two Super Bowls, but lost them both. The good times don’t last forever. It’s time to cash in.

Written and directed by Jon Bois

Written and produced by Alex Rubenstein

Rights specialist Lindley Sico

Secret Base executive producers Will Buikema and Jon BoisKnown goofs:

• At about the 42-minute mark, Jon says Fran Tarkenton held a 45-8-1 record as starter between 1973 and 1976. His record across these years was actually 43-10-1.

(more…)

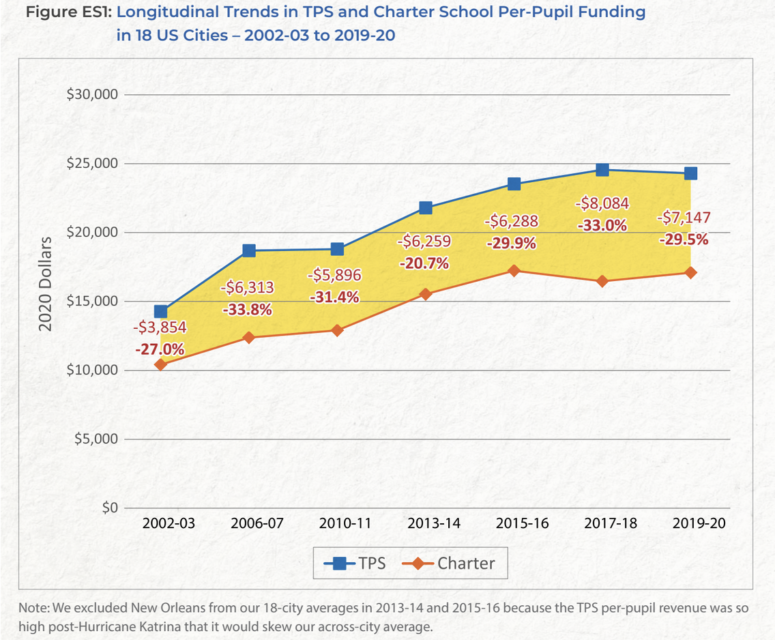

Charter school students do better academically, yet are funded at a lower level than other students

Jack Elbaum on recent studies that show charter schools in the United States have higher academic success rates than ordinary state-funded schools, despite a significantly lower funding rate:

If you thought charter schools received anywhere near the same amount of funding as traditional public schools, then think again.

A new, massive study from the University of Arkansas finds that “On average, charter schools across 18 cities in 16 states (…) receive about 30 percent or $7,147 (2020 dollars) less funding per pupil than traditional public schools.” Over the past two decades, this funding disparity has remained relatively stable.

The gaps are, predictably, more severe in some places than others. The study notes that “Atlanta has the largest percentage-based charter funding disparity (about 53 percent), while Camden has the largest disparity in dollars ($19,711). Houston has the smallest disparity in terms of percent (three percent) and dollars ($417).”

Importantly, the regression analysis run by the authors did not suggest differences in the proportion of students in poverty or English Language Learners are the reason for the disparity. However, it did find that after taking into account differences in the number of special needs students, the disparity dropped considerably — although it remained significant ($1,707).

[…]

Based on these data alone, it would not be unreasonable for one to expect that these charter schools had worse educational outcomes than their traditional public school counterparts.

The only issue is that this is not the case.

A recent study from Stanford University, for example, found that charter school students gain 16 days’ worth of reading and six days of math per year relative to those in traditional public schools. These benefits were particularly pronounced among minority students who were also in poverty. Education Week reported that “Black charter students in poverty gained 37 days of learning in reading and 36 days in math over their counterparts in traditional public schools, and Hispanic students in poverty gained 36 days of reading and 30 days of math over their traditional public school peers.”

Economist Thomas Sowell’s 2020 book Charter Schools and Their Enemies also offers compelling data suggesting the efficacy of charter schools. He studied a set of charters and traditional public schools in New York City that served essentially identical populations. In many cases in the study, a charter school and traditional public school would even occupy the same building.