Army University Press

Published 20 Dec 2023Between 20 and 28 December 1943, the idyllic Adriatic resort town of Ortona, Italy was the scene of some of the most intense urban combat in the Mediterranean Theater. Soldiers of the First Canadian Infantry Division fought German Falschirmjager for control of the city, the eastern anchor of the Gustav Line. The Army University Films Team is proud to present, The Battle of Ortona, as told by Major Jayson Geroux of the Canadian Armed Forces.

December 21, 2023

The Battle of Ortona

September 2, 2023

Trial Run for D-Day – Allied Invasion of Sicily 1943

Real Time History

Published 1 Sept 2023After defeating the Axis in North Africa, the stage was set for the first Allied landing in Europe. The target was Sicily and in summer 1943 Allied generals Patton and Montgomery set their sights on the island off the Italian peninsula.

(more…)

August 27, 2023

The Liberation of Paris – WW2 – Week 261 – August 26, 1944

World War Two

Published 26 Aug 2023Paris is liberated by the Allies, a symbolic act that causes the world to rejoice. Something far more important to the course of the war, though, happens this week in Romania. The Allies continue to advance in the south of France and begin a new offensive in Italy, though the Pacific War has quietened down once again.

(more…)

July 20, 2023

The Fights for Assoro & Leonforte with Mark Zuehlke

OTD Military History

Published 19 Jul 2023Join me as I have Mark Zuehlke back on the channel to discuss the fights for Assoro and Leonforte during the campaign in Sicily.

(more…)

December 26, 2022

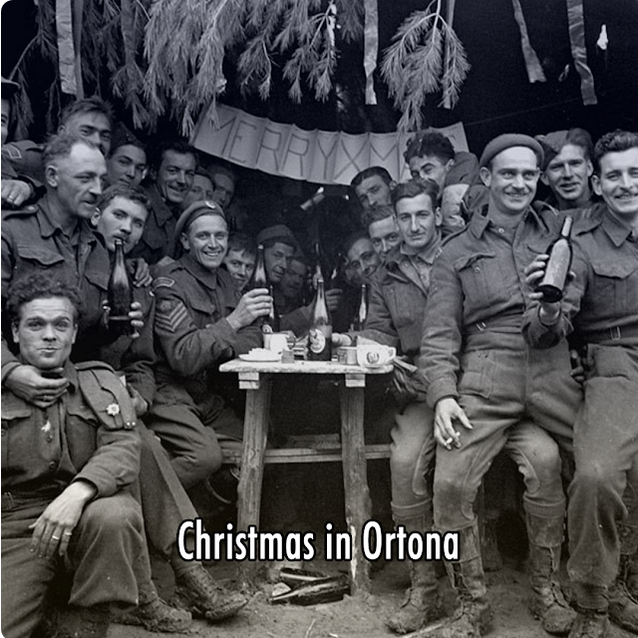

2nd Canadian Infantry Brigade Christmas celebrations in Ortona, 1943

The folks at the World War Two channel on YouTube posted this to their community page on Christmas Day:

On Christmas Day, 25 December 1943, the 1st Canadian Infantry Division is still engaged in brutal urban combat against the 1. Fallschirmjäger-Division for control over the town of Ortona. But among the rubble of the “Italian Stalingrad”, soldiers of the Seaforth Highlanders of Canada, along with other units [of the 2nd Canadian Infantry Brigade], manage to keep the Christmas spirit alive.

Colonel S. W. Thomson will recount this most unusual Christmas celebration many years later:

“I knew that we would be fully engaged with the enemy on Christmas day. However our most enterprising Quartermaster, Captain Bordon Cameron, was anxious to provide something special for the men at Christmas. Three companies were in the line with one in reserve, often the norm. We decided to feed the reserve company first and feed the remaining companies in relays. as one company finished it would go forward some 300 or 400 yards and relieve the next. Tables, linen, chinaware and candles were scrounged by the reserve company. The tables were set up in rows in our great church Santa Maria with four foot thick walls and my rear H.Q. What a picture, what an appropriate setting for a Christmas dinner on Dec. 25.

“Soup, roast pork, vegetables and Christmas pudding along with a bottle of beer for each of the tattered, scruffy, war weary soldiers was served by HQ and B echelon staff. The Q.M. boys excelled themselves, the impossible had happened. There was a spirit of good-fellowship throughout the church. The signals officer Lieutenant Wilf Gildersleeve played the organ, and our much loved padre Roy Durford led the carol singing. Pipe Major Esson played his pipes several times during the meals drowning out the odd enemy shell burst outside.

“Christmas in Ortona, the meal, yes, but the spirit of the occasion, the look on the faces of those exhausted, gutsy men on entering the church is with me to-day and will live forever.”

To all our followers, readers, and viewers: We wish you a Merry Christmas!

From: Canadian Military History, Vol. 2 (1993)

Picture: Canadian soldiers celebrate Christmas in Ortona, Italy

Source: Canadian Armed Forces

December 25, 2022

Stalin’s Christmas Surprise – Major Offensives to Come – WW2 – 226 – December 24, 1943

World War Two

Published 24 Dec 2022Twas the night before Christmas and the war was grinding on. The Moro River Campaign continues in Italy with Canadian infantry pushing past the Gully and into “Little Stalingrad”. Generally, the Allied advance to Rome is turning into a stalemate though, but Winston Churchill still believes an amphibious landing is the way to break this. Joseph Stalin also has some pretty big plans to bring the USSR back to its pre-Barbarossa borders. In the Pacific, there is attrition over Rabaul and stalemate on Bougainville.

(more…)

July 14, 2022

The plight of 1st Canadian Infantry Division during the opening stages of Operation Husky, July 1943

First Canadian Infantry Division had an exciting start to Operation Husky — for certain values of “exciting” — as told in Mark Zuehlke’s Operation Husky: The Canadian Invasion of Sicily, July 10-August 7, 1943:

Every day [during the convoy to Sicily], Major General Guy Simonds and Lieutenant Colonel George Kitching performed the same macabre ritual. Kitching would take a hat filled with equal-sized chits of paper on which the names of every ship bearing Canadian personnel and equipment was written and hold it out to the divional commander. Simonds drew three chits and those three ships were declared lost, victims of torpedoes from a German U-boat — the scenario at times being that about one thousand men aboard the fast convoy had drowned and burned in oil-drenched seas, or hundreds of trucks, tanks, guns, radios, and other equipment in the slow convoy had plummeted to the bottom of the Mediterranean. All lost, gone. Kitching and his staff would then sit down and coldly “examine the effect the loss of these three ships would have on our projected plans.”

On July 3, Simonds pulled from the hat chits for three ships travelling in the Slow Assault Convoy — City of Venice, St. Essylt, and Devis. The coincidence was chilling, for it was aboard these vessels that equal portions of the divisional headquarters equipment — including all the trucks, Jeeps, radio sets, and a panoply of other gear that kept a division functioning — had been distributed. Were one or even, God forbid, two of these ships sunk, the headquarters could function almost as normal. But lose the three and the division was crippled.

Kitching considered the “chance of all three ships being sunk as a million to one”. Deciding there was no point in studying the implications of such a wildly remote possibility, he asked Simonds to draw another three names from the hat, which the general did.

As you’ve probably already figured out, the one-in-a-million situation turned up on schedule. City of Venice took a torpedo during a submarine alert, with Royal Navy escort ships dropping depth charges on a suspected U-boat position. The convoy instructions were for damaged ships to be left behind and for the undamaged ships to carry on, as the danger was greater if the whole convoy slowed or stopped to aid the stricken ship(s). City of Venice could not be saved, and ten crew members and ten Canadian soldiers were killed, but the other 462 men on board were transferred to a rescue ship. A few hours later, two more ships from the convoy were lost: St. Essylt, and Devis.

While the loss of lives aboard the three torpedoed slow convoy ships was relatively small, the amount and nature of equipment and stores sent to the bottom of the Mediterranean was serious. A total of 562 vehicles were lost, leaving 1st Canadian Infantry Division facing a major transportation shortage. Also lost were fourteen 25-pounders [gun-howitzers], eight 17-pounders [heavy anti-tank guns, equivalent to German 88mm guns], and ten 6-pounder anti-tank guns that would significantly reduce the division’s artillery support. “In addition to the above,” the divisional historical officer, Captain Gus Sesia, noted in his diary, “we lost great quantities of engineers’ stores and much valuable signals equipment.” The biggest immediate blow was the loss of all divisional headquaters vehicles and equipment, including many precious wireless sets — precisely the nightmare scenario forecast and rejected by Kitching as infeasible when Simonds had drawn these ships by lot a few days earlier.

Equally serious was the loss in equipment and lives suffered by the Royal Canadian Army Medical Coprs personnel attached to the division. Due to a loading error, instead of No. 9 Field Ambulance’s vehicles being distributed among several ships, fifteen out of eighteen were on Devis. Accompanying the vehicles was a medical officer and nineteen other ranks and medical orderlies. Four of the other ranks were among the fifty-two Canadian troops killed and another four suffered injuries. The other field ambulance, field dressing station, and field surgery units assigned to the division were largely unaffected. No. 5 Field Ambulance’s vehicles had been distributed correctly so only two of them and a ton of medical supplies went down with St. Essylt. City of Venice had just one medical officer, Captain K.E. Perfect, aboard and he escaped uninjured. But Perfect was overseeing safe passage of nine tons of stretchers and blankets, which all went to the bottom.

[…]

A fully accounting of the losses would not be completed for days. Even on July 7, reports were still coming in that City of Venice remained under tow and bound for Algiers. Finally, at 1900 hours on that day, its sinking was confirmed. The report also stated that most of the surviving Canadian troops had been loaded on a Landing Craft, Infantry in Algiers and were en route for Malta. From there, they would eventually rejoin the division.

Compounding the loss of so many vehicles was the fact that the division had left Britain with a smaller than mandated number due to lack of shipping capacity. Once the seriousness of the situation was appreciated, Lieutenant Colonel D.G.J. Farquharson, the division’s assistant director of ordnance services, and his staff “tried to make [the losses] good … by emergency measures, improvising and obtaining what could be obtained buckshee from the Middle East.” They soon had commitments for some vehicles, but these would not be available until after the initial landings. The fact that every vehicle to be found locally was a Dodge posed “a considerable ordnance problem, because what spare parts we had were based on Ford and Chevrolet makes.” Improvisation would be the order of the day.

July 10, 2018

Operation Husky with the “D-Day Dodgers”

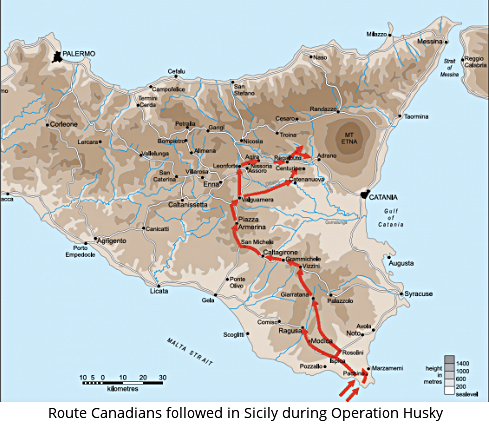

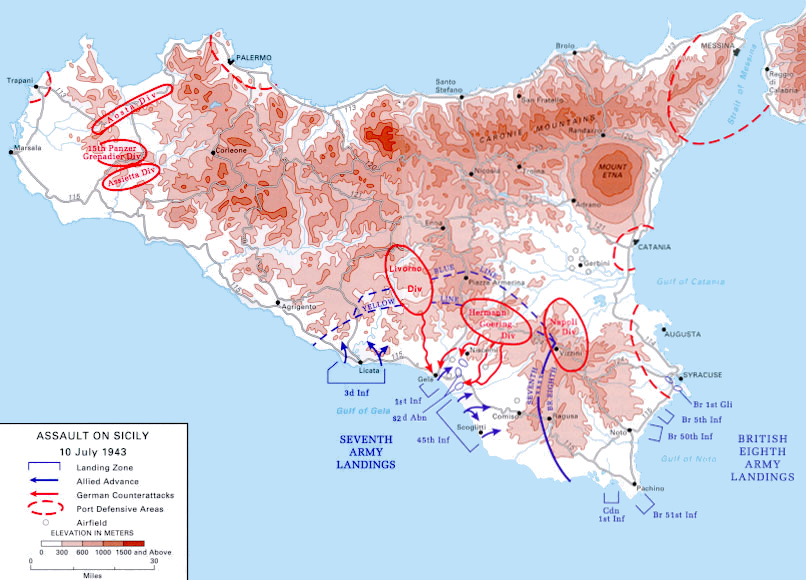

On this day in 1943, the Allies invaded Sicily as their first step toward knocking Italy out of the war. It was the first major allied operation (other than the abortive Operation Jubilee in 1942) in which a major formation of the Canadian Army took part. The 1st Canadian Infantry Division under the command of Major General Guy Simonds was part of General Montgomery‘s Eighth Army, which landed on the southeast coast of the island.

The Canada History Project describes the Canadian participation in Operation Husky:

The men were young, of course, many just 18 to 24 years old. The roads were narrow dirt tracks switchbacking over steep, volcanic mountains. Temperatures hovered around 37 degrees, turning water bottles into hot water bottles, as one soldier put it. Three dry and dusty weeks into the campaign, there was a five-hour downpour, and all the troops relished the chance to shower off the dirt caked to their skin. By this time they were well into the middle of the island where their enemy was the fierce Hermann Goering division of the German army.

For six weeks, from July 10th to August 17th 1943, the Canadians, fighting as an independent unit for the first time, slogged through the interior of Sicily as part of Operation Husky, the first stage of taking back Europe from the Nazis after four years of war. Meanwhile, the Americans skirted the more level western coastline of the island and the British came up the east side, each competing with the other for glory.

American General Patton wrote in a letter, “This is a horse race in which the prestige of the US Army is at stake…we must take Messina before the British.”

That may be the way the generals saw it. For the soldiers, pushing through, village by village, mountaintop by mountaintop, it was no game.

Sicily, a rural mountainous island known for its orange groves and almond orchards, olives and the Mafia, sits strategically in the Mediterranean off the foot of Italy. The Canadian contingent was 25,000 strong. All men and materials were brought in by sea, making it the largest amphibious operation yet, though D-Day, a year later, would be bigger still.

In the first few days the Canadians passed through an area that is now a Unesco World Heritage site. Today tourists come to this southeast corner of Sicily to see the restored baroque architecture. But the young Canadian lads were eyeing the pillboxes, watching for snipers and lookouts. In the early days many Italian soldiers surrendered without too much resistance and the local people gave them grapes and oranges to quench their thirst in the scorching heat.

[…]

Operation Husky did succeed in gaining back the first European soil for the Allies. In the midst of it, Mussolini resigned and soon after Italy surrendered, another goal of the campaign. It started a second front forcing Hitler to back off his aggressive attack on our ally, Russia. And it provided a rehearsal for the larger amphibious landing on the beaches of Normandy, France in June of 1944. As well, it was the first time Canadians had fought as an independent unit. Their young commander was Guy Simonds. 1200 Canadians were wounded in Sicily and 562 died there. 490 of them are buried in the Canadian cemetery at Agira.

For their efforts, the soldiers fighting in Sicily and Italy became known as the “D-Day Dodgers”, a careless epithet supposedly delivered by Lady Astor, but embraced by the soldiers themselves who, with some sarcastic humour, turned it into the song, “We are the D-Day Dodgers, in sunny Italy…”

The Canadian part of the campaign from canadiansoldiers.com:

Sailing secretly at the end of June, the Division took its place on the left flank of General Bernard Montgomery’s famed Eighth Army for the Sicilian landings. The amphibious attack against Pachino peninsula was an unqualified success. The defenders were surprised and overrun with very few Allied casualties, and so began a controversial 38-day campaign. General Simonds’ troops advanced inland under difficulties:

The weather was extremely hot, the roads extremely dusty, and there was little transport; the troops were fresh from a temperate climate and a long voyage in crowded ships; and even though for a time there was scarcely any opposition, mere marching was a very exhausting experience under these conditions.

Continuing over the rocky terrain, they had their first fight with the Germans at Grammichele on 15 July. Three days later they captured Valguarnera. Both were rear-guard actions by a withdrawing enemy, and the first real tests came on the July 20 at Assoro and Leonforte. At the former, the 1st Brigade launched a surprise attack at night against an ancient Norman stronghold on the summit of a lofty peak. They seized and held their place in the face of fierce counter attacks, the records for the 15th Panzer Grenadier Division afterwards revealing generous tributes to the fieldcraft (Indianerkrieg) of the Canadians. Leonforte, an equally difficult situation, was captured by the 2nd Brigade after a bitter fight. These three days cost the Division about 275 casualties.

The advance then turned the east towards Adrano, at the base of Mount Etna. In their path stood Agira, “one of the most imposing of Sicily’s innumerable hill-towns,” and in the neighbouring hills the enemy put up a stubborn resistance. Both the 1st and 2nd Brigades were heavily engaged during the last week of July. The operations were, however, effectively supported by Canadian tanks and by the divisional artillery, reinforced by units of the Royal Artillery. General Simonds also had temporarily under his command the 231st British Infantry Brigade (the Malta Brigade), which threatened German communications from the south. After a bitter struggle Agira was captured on the 28th. Between Agira and Adrano the Hermann Goering Division made a stand at Regalbuto, using tanks as pillboxes in the debris of the town. While part of the 1st Division loosened the enemy’s grip on this town, the 3rd Brigade, temporarily under the command of the British 78th Infantry Division, assisted that formation in the Dittaino Valley.

American encircling operations in the western and northern districts of the island, combined with steady British pressure north of the Catania Plain, forced the enemy out of the defences based on Etna, and the campaign ended when the Allies entered Messina on 16-17 Aug. The 1st Division had performed all of its allotted tasks and had acquired valuable battle experience at a total cost of 2,155 casualties. The measure of the achievement was contained in General Montgomery’s statement: “I now consider you one of my veteran Divisions.”

The Division passed from XXX Corps to XIII Corps on 10 Aug, and moved to a concentration area in the rear on 11-13 Aug, relieved of operational responsibilities. Divisional headquarters moved to Francofonte. During the battle of Sicily they had travelled 120 miles, over largely rough and mountainous terrain.

December 6, 2011

The Battle of Ortona

The Laurier Centre for Military Strategic and Disarmament Studies is marking the anniversary of the Battle of Ortona in 1943 by sending Twitter updates from @BattleOfOrtona to outline the historical events of the 1st Canadian Division and the 1st Canadian Armoured Brigade in this key battle of the Italian Campaign. Here is the situation just before the battle opened, from Terry Copp:

The Canadians were involved in a series of isolated battles in the mountains of Central Italy in November 1943 when General Bernard Law Montgomery issued orders for an advance up the Adriatic Coast to seize control of the east-west road Pescara to Rome. The American 5th Army was to launch a direct advance towards Rome at the same time.

The Canadians were still in the mountains when British, Indian, and New Zealand troops fought their way across the Sangro River, forcing a German withdrawal to the Moro River. The 78th British “Battleaxe” Division had shot its bolt at the Sangro and Montgomery ordered the fresh, full strength Canadian Division to take over the advance on the coastal flank. The move was to be completed by the night of 5 December.

The German 10th Army, responsible for the defence of Italy east of the Appenine Mountains, contained 12 divisions — 10 infantry and 2 armoured. The 76 Panzer Corps held the river lines south of Pescara with 1st Parachute, 90th Panzer Grenadier, 26th Panzer and 65th Infantry divisions. Normally an attacker needs to outnumber the defender by at least 3:1. This ratio could not be achieved in December 1944 and with the beginning of heavy winter rains air power could only play a small role. Everyone but the infantry was optimistic.