World War Two

Published 10 Dec 2022There are plans afoot to hit the enemy from behind in Italy. Allied leaders are meeting again in Cairo to go over other plans, notably what to do about China and Burma. There is active fighting on two fronts in Italy too, though this week it doesn’t go particularly well for the Allies. Attacks in the USSR are unsuccessful for the Soviets, but do go well for the Germans, and there are Allied attacks by air in the Marshall Islands and over France.

(more…)

December 11, 2022

An Amphibious Landing to take Rome? – 224 – December 10, 1943

December 8, 2022

Is the Luftwaffe Defeated in 1943? – WW2 Documentary Special

World War Two

Published 7 Dec 2022Outnumbered and outproduced, the once mighty Luftwaffe is battling to hold its own across three fronts. Every month brings new pain for the force. But the Luftwaffe still has a few tricks up its sleeves and can make the Allies bleed heavily. If only Hitler and the Nazi leadership weren’t sabotaging its chances …

(more…)

December 6, 2022

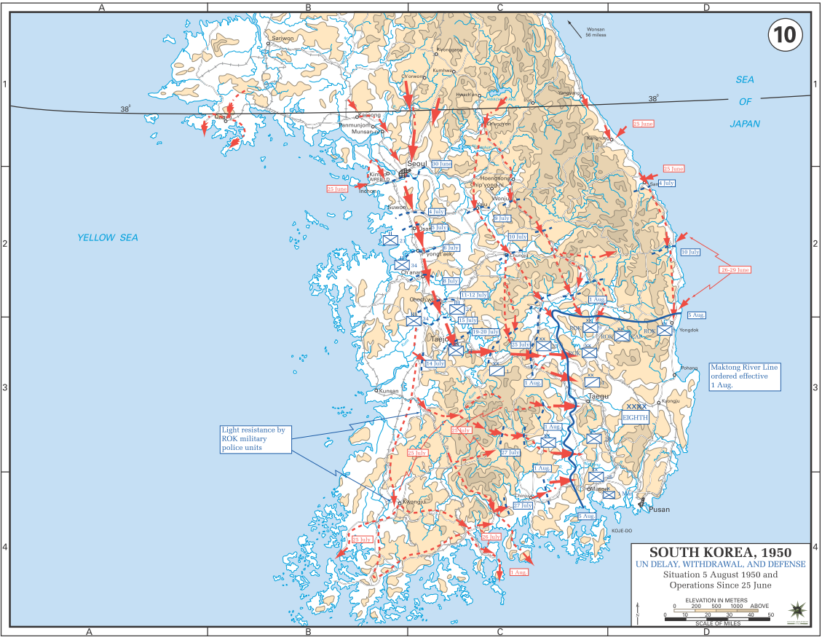

The coming of the Korean War

In Quillette, Niranjan Shankar outlines the world situation that led to the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950:

Initial phase of the Korean War, 25 June through 5 August, 1950.

Map from the West Point Military Atlas — https://www.westpoint.edu/academics/academic-departments/history/korean-war

The Korean War was among the deadliest of the Cold War’s battlegrounds. Yet despite yielding millions of civilian deaths, over 40,000 US casualties, and destruction that left scars which persist on the peninsula today, the conflict has never received the attention (aside from being featured in the sitcom M*A*S*H) devoted to World War II, Vietnam, and other 20th-century clashes.

But like other neglected Cold War front-lines, the “Forgotten War” has fallen victim to several politicized and one-sided “anti-imperialist” narratives that focus almost exclusively on the atrocities of the United States and its allies. The most recent example of this tendency was a Jacobin column by James Greig, who omits the brutal conduct of North Korean and Chinese forces, misrepresents the underlying cause of the war, justifies North Korea’s belligerence as an “anti-colonial” enterprise, and even praises the regime’s “revolutionary” initiatives. Greig’s article was preceded by several others, which also framed the war as an instance of US imperialism and North Korea’s anti-Americanism as a rational response to Washington’s prosecution of the war. Left-wing foreign-policy thinker Daniel Bessner also alluded to the Korean War as one of many “American-led fiascos” in his essay for Harper’s magazine earlier this summer. Even (somewhat) more balanced assessments of the war, such as those by Owen Miller, tend to overemphasize American and South Korean transgressions, and don’t do justice to the long-term consequences of Washington’s decision to send troops to the peninsula in the summer of 1950. By giving short shrift to — or simply failing to mention — the communist powers’ leading role in instigating the conflict, and the violence and suffering they unleashed throughout it, these depictions of the Korean tragedy distort its legacy and do a disservice to the millions who suffered, and continue to suffer, under the North Korean regime.

Determining “who started” a military confrontation, especially an “internal” conflict that became entangled in great-power politics, can be a herculean task. Nevertheless, post-revisionist scholarship (such as John Lewis Gaddis’s The Cold War: A New History) that draws upon Soviet archives declassified in 1991 has made it clear that the communist leaders, principally Joseph Stalin and North Korean leader Kim Il-Sung, were primarily to blame for the outbreak of the war.

After Korea, a Japanese imperial holding, was jointly occupied by the United States and the Soviet Union in 1945, Washington and Moscow agreed to divide the peninsula at the 38th parallel. In the North, the Soviets worked with the Korean communist and former Red Army officer Kim Il-Sung to form a provisional “People’s Committee”, while the Americans turned to the well-known Korean nationalist and independence activist Syngman Rhee to establish a military government in the South. Neither the US nor the USSR intended the division to be permanent, and until 1947, both experimented with proposals for a united Korean government under an international trusteeship. But Kim and Rhee’s mutual rejection of any plan that didn’t leave the entire peninsula under their control hindered these efforts. When Rhee declared the Republic of Korea (ROK) in 1948, and Kim declared the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) later that year, the division was cemented. Each nation threatened to invade the other and began preparing to do so.

What initially prevented a full-scale attack by either side was Washington’s and Moscow’s refusal to provide their respective partners with support for the military reunification of the peninsula. Both superpowers had withdrawn their troops by 1949 to avoid being dragged into an unnecessary war, and the Americans deliberately withheld weapons from the ROK that could be used to launch an invasion.

However, Stalin began to have other ideas. Emboldened by Mao Zedong’s victory in the Chinese Civil War and frustrated by strategic setbacks in Europe, the Soviet premier saw an opportunity to open a “second-front” for communist expansion in East Asia with Beijing’s help. Convinced that Washington was unlikely to respond, Stalin gave Kim Il-Sung his long-sought “green-light” to reunify the Korean peninsula under communist rule in April 1950, provided that Mao agreed to support the operation. After Mao convinced his advisers (despite some initial difficulty) of the need to back their Korean counterparts, Red Army military advisers began working extensively with the Korean People’s Army (KPA) to prepare for an attack on the South. When Kim’s forces invaded on June 25th, 1950, the US and the international community were caught completely off-guard.

Commentators like Greig, who contest the communists’ culpability in starting the war, often rely on the work of revisionist historian Bruce Cumings, who highlights the perpetual state of conflict between the two Korean states before 1950. It is certainly true that there were several border skirmishes over the 38th parallel after the Soviet and American occupation governments were established in 1945. But this in no way absolves Kim and his foreign patrons for their role in unleashing an all-out assault on the South. Firstly, despite Rhee’s threats and aggressive posturing, the North clearly had the upper hand militarily, and was much better positioned than the South to launch an invasion. Whereas Washington stripped Rhee’s forces of much of their offensive capabilities, Moscow was more than happy to arm its Korean partners with heavy tanks, artillery, and aircraft. Many KPA soldiers also had prior military experience from fighting alongside the Chinese communists during the Chinese Civil War.

Moreover, as scholar William Stueck eloquently maintains, the “civil” aspect of the Korean War fails to obviate the conflict’s underlying international dimensions. Of course, Rhee’s and Kim’s stubborn desire to see the country fully “liberated” thwarted numerous efforts to establish a unified Korean government, and played a role in prolonging the war after it started. It is unlikely that Stalin would have agreed to support Pyongyang’s campaign to reunify Korea had it not been for Kim’s persistent requests and repeated assurances that the war would be won quickly. Nevertheless, the extensive economic and military assistance provided to the North Koreans by the Soviets and Chinese (the latter of which later entered the war directly), the subsequent expansion of Sino-Soviet cooperation, the Stalinist nature of the regime in Pyongyang, Kim’s role in both the CCP and the Red Army, and the close relationship between the Chinese and Korean communists all strongly suggest that without the blessing of his ideological inspirators and military supporters, Kim could not have embarked on his crusade to “liberate” the South.

Likewise, Rhee’s education in the US and desire to emulate the American capitalist model in Korea were important international components of the conflict. More to the point, all the participants saw the war as a confrontation between communism and its opponents worldwide, which led to the intensification of the Cold War in other theaters as well. The broader, global context of the buildup to the war, along with the UN’s authorization for military action, legitimized America’s intervention as a struggle against international communist expansionism, rather than an unwelcome intrusion into a civil dispute among Koreans.

December 4, 2022

Operation Overlord Confirmed at Teheran – WW2 – 223 – December 3, 1943

World War Two

Published 3 Dec 2022The Teheran Conference is in full swing and the Allied leadership and plan for a cross channel invasion of Europe is agreed upon by Stalin, Churchill, and Roosevelt. There are new Allied attacks across Italy, but at Bari a German air raid releases deadly poison gas.

(more…)

December 1, 2022

The NKVD Making Fools of German Intelligence – Spies & Ties 25

World War Two

Published 30 Nov 2022Colonel Reinhard Gehlen is head of German military intelligence in the East. He likes to think he’s a master of his craft. But all along he’s been a victim of the NKVD and a man named Max. Gehlen thinks he can hold off the Red Army. But as things go from bad to worse his thoughts will start to turn to the possibility of a new world …

(more…)

Crisis? Which crisis?

In The Line, Matt Gurney makes the case that was NATO (and western governments in general) needs is something called “deliverology”:

I couldn’t have asked for a more topical example of exactly what I’m talking about here: the lull between realization and reaction. There were no problems with “expectations” at the top of the federal government in February [during the Freedom Convoy 2022 protests]. Everyone in a position of authority was seized with the urgency of the situation and the need for rapid action. There wasn’t any denial, doubt or incomprehension, which are the usual enemies when I write about our expectations being a problem.

February was an example of a different issue: realizing there was a crisis but not really knowing what to do about it, or whose job it was to do it, and wasting a lot of precious time trying to figure it all out. When days and even hours count, governments can’t spend weeks or months figuring out what to do. But that’s what happened during the convoys, and during COVID, and other incidents I could rattle off. Does anyone think it won’t happen again next time, whatever that threat may be?

And some version of that concern came up over and over in Halifax [at the Halifax International Security Forum]. And not just among Canadians. The world is changing very quickly and even when we recognize a problem, we aren’t moving fast enough to keep up. So on top of our expectations, we’ve got another challenge: response times. They’re just too damned long.

I hope the readers will forgive me for being a little vague in this next section; some of the conversations I’m thinking of here were in off-the-record sessions. Rather than trying to splice together any specific quote or anecdote, I’ll just wrap it all up under the theme of “There are things we should be doing now that we weren’t, and things we should have been doing a long time ago that we only started on way too late.”

An obvious example? The rush to get Europe off of Russian fossil fuels and on to either locally generated renewables or energy imports from allies and friendly nations. (If only there was a “business case” for Canada doing more. Sigh.) Another fascinating example that came up was air defences. Two decades of post-Cold-War-style thinking among the allies has led to widespread neglect among the NATO countries of air-defence weapons. Why bother? The Taliban didn’t have an air force, right?

Most countries have fighter jets and inventories of air-to-air missiles suitable for their planes. However, across the alliance, there are very few ground-based air-defence systems suited to shooting down not just attacking aircraft, but incoming cruise missiles and drones.

Drones pose a particular challenge. They fly slow and low and are highly manoeuvrable, plus they are so cheap that they can be a true asymmetrical weapon: you’ll go broke real quick firing million-dollar missiles at a drone that costs your enemy $50,000 or so. And your enemy may send a few hundred at once in a swarm that simply overwhelms your defences. It’s not that drones are unbeatable. The opposite is true: drones are easily destroyed, if you have the right defences available.

We don’t, though. Oops.

The NATO powers actually had a preview of this element of the ongoing war between Ukraine and Russia during the 2020 conflict between Azerbaijan and Armenia, where drones were used to devastating effect. Every military affairs watcher I know sat up a bit straighter after watching what the Azeris did to Armenia, with shocking speed. Swarms of drones first killed Armenia’s air defences and then went to work on Armenian ground forces. The U.S. and NATO allies have been studying that conflict, and considering how to adapt our own strategies, for both offence and defence. But right now, nine months into the Ukraine war and two years after the conflict in the Caucasus, there still aren’t enough NATO systems available even for our own needs, let alone to share with Ukraine. Russia keeps hammering away at critical Ukrainian civilian infrastructure and the Ukrainians keep begging for help, but we have nothing to send. To be clear, a few systems have been sent to Ukraine, which include not just the weapons but the radars and computers necessary to detect and engage targets. But they can only be delivered as fast as they can be built. There is no real production pipeline here, and certainly no pre-stocked inventories in NATO armouries.

November 29, 2022

Near Peer: Russia

Army University Press

Published 25 Nov 2022AUP’s Near Peer film series continues with a timely discussion of Russia and its military. Subject matter experts discuss Russian history, current affairs, and military doctrine. Putin’s declarations, advances in military technology, and Russia’s remembrance of the Great Patriotic War are also addressed. “Near Peer: Russia” is the second film in a four-part series exploring America’s global competitors.

November 27, 2022

The Costliest Day in US Marine History – WW2 – 222 – November 26, 1943

World War Two

Published 26 Nov 2022The Americans attack the Gilbert Islands this week, and though they successfully take Tarawa and Makin Atolls, it is VERY costly in lives, and show that the Japanese are not going to be defeated easily. They also have a naval battle in the Solomons. Fighting continues in the Soviet Union and Italy, and an Allied conference takes place in Cairo, a prelude for a major one in Teheran next week.

(more…)

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn and One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich

In Quillette, Robin Ashenden discusses the life experiences of Aleksandr Slozhenitsyn that informed the novel that made him famous:

The book was published less than 10 years after the death of Joseph Stalin, the dictator who had frozen his country in fear for nearly three decades and subjected his people to widespread deportation, imprisonment, and death. His successor Nikita Khrushchev — a man who, by his own admission, came to the job “elbow deep in blood” — had set out on a redemptive mission to liberalise the country. The Gulags had been opened and a swathe of prisoners freed; Khrushchev had denounced his predecessor publicly as a tyrant and a criminal and, at the 22nd Party Congress in October 1961, a full programme of de-Stalinisation had been announced. As for the Arts, previously neutered by the Kremlin’s policy of “Socialist Realism” — in which the values of Communism had to be resoundingly affirmed — they too were changing. Now, a new openness and a new realism was called for by Khrushchev’s supporters: books must tell the truth, even the uncomfortable truth about Communist reality … up to a point. That this point advanced or retreated as Khrushchev’s power ebbed and flowed was something no writer or publisher could afford to miss.

Solzhenitsyn’s book told the story of a single day in the 10-year prison-camp sentence of a Gulag inmate (or zek) named Ivan Denisovich Shukhov. Following decades of silence about Stalin’s prison-camp system and the innocent citizens languishing within it, the book’s appearance seemed to make the ground shake and fissure beneath people’s feet. “My face was smothered in tears,” one woman wrote to the author after she read it. “I didn’t wipe them away or feel ashamed because all this, packed into a small number of pages … was mine, intimately mine, mine for every day of the fifteen years I spent in the camps.” Another compared his book to an “atomic bomb”. For such a slender volume — about 180 pages — the seismic wave it created was a freak event.

As was the story of its publication. By the time it came out, there was virtually no trauma its author — a 44-year-old married maths teacher working in the provincial city of Ryazan — had not survived. After a youth spent in Rostov during the High Terror of Stalin’s 1930s, Solzhenitsyn had gone on to serve eagerly in the Red Army at the East Prussian front, before disaster struck in 1945. Arrested for some ill-considered words about Stalin in a letter to a friend, he was handed an eight-year Gulag sentence. In 1953, he was sent into Central Asian exile, only to be diagnosed with cancer and given three weeks to live. After a miraculous recovery, he vowed to dedicate this “second life” to a higher purpose. His writing, honed in the camps, now took on the ruthless character of a holy mission. In this, he was fortified by the Russian Orthodox faith he’d rediscovered during his sentence, and which had replaced his once-beloved, now abandoned Marxism.

Solzhenitsyn had, since his youth, wanted to make his mark as a Russian writer. In the Gulag, he’d written cantos of poetry in his head, memorized with the help of matchsticks and rosary beads to hide it from the authorities. During his Uzbekistan exile, he’d follow a full day’s work with hours of secret nocturnal writing about the darker realities of Soviet life, burying his tightly rolled manuscripts in a champagne bottle in the garden. Later, reunited with the wife he’d married before the war, he warned her to expect no more than an hour of his company a day — “I must not swerve from my purpose.” No friendships — especially close ones — were allowed to develop with his fellow Ryazan teachers, lest they take up valuable writing time, discover his perilous obsession, or blow his cover. Subterfuge became second nature: “The pig that keeps its head down grubs up the tastiest root.” Yet throughout it all, he was sceptical that his work would ever be available to the general public: “Publication in my lifetime I must put out of my mind.”

After the 22nd Party Congress, however, Solzhenitsyn recognised that the circumstances were at last propitious, if all too fleeting. “I read and reread those speeches,” he wrote later, “and the walls of my secret world swayed like curtains in the theatre … had it arrived, then, the long-awaited moment of terrible joy, the moment when my head must break water?” It seemed that it had. He got out one of his eccentric-looking manuscripts — double-sided, typed without margins, and showing all the signs of its concealment — and sent it to the literary journal of his choice. That publication was the widely read, epoch-making Novy Mir (“New World”), a magazine whose progressive staff hoped to drag society away from Stalinism. They had kept up a steady backwards-forwards dance with the Khrushchev regime throughout the 1950s, invigorated by the thought that each new issue might be their last.

November 25, 2022

Our old, comfortable geopolitical certainties are becoming less comfortable and less certain

In The Line, Matt Gurney discusses a few of the things he heard at the recent Halifax International Security Forum:

First, though, I wanted to explore that grim feeling that swept over me as Forum president Peter Van Praagh stepped up to the lectern and opened the formal proceedings with a review of the geopolitical situation, and how we got here.

From his prepared remarks (slightly trimmed):

Last year … we marked the 20th anniversary of 9/11. It was not an auspicious anniversary. Just months earlier, the United States and its allies withdrew their troops from Afghanistan and discarded the hopes and dreams of so many Afghans … [it] was a low point for Afghanistan and indeed, for all of us. … It was the culmination of 20 years of good intentions. And bad results:

The decisions made in the immediate aftermath of 9/11, North Korea going nuclear, Russia’s invasion of Georgia, the Great Recession, Iran, the Arab Spring and the Syrian civil war, the surge of refugees — more than at any time in human history, the successful rise of populist politics, the higher than necessary death toll from coronavirus, Hong Kong losing its freedoms, January 6 and its wake, climate-change disasters, and our withdrawal from Afghanistan …

It was a tragic end to a 20-year tragic era.

That’s a pretty depressing list. Right?

As a student of history, I always strive to avoid too much recency bias. Most of the things you hear described as “unprecedented” aren’t anything remotely close to that. The general public has a memory of a few years — maybe a generation. We definitely do face some novel challenges today, but we are still better off than most generations in human history, and it’s not even close.

Still. Van Praagh offered a bleak if concise catalogue of tragedy and struggle. And there are some notable absences. The Iraq War, for instance, is probably worth noting as a specific event, not just part of the Sept. 11th fallout. Perhaps the Libyan intervention as well. Some of China’s more aggressive actions, especially at home, also come to mind.

But as I mulled over that terse version of early-21st-century history, something else jumped out at me: most of those threats were things that happened far away and to other people.

I mentioned recency bias above, so it’s only fair to note a different bias: “far away” and “other people” depends on the vantage point, doesn’t it? Every event listed above was a direct and local tragedy for the people caught in the middle of it, who don’t have the luxury of viewing these events at a comfortable remove, the way the West generally has.

The pandemic, of course, did not spare the West. Nor did the Great Recession, the toll of a changing climate and the populist upheavals roiling the democracies. Those are local problems for us all.

The military challenges, though, are getting more and more local, aren’t they? North Korea seemed far away once; today it’s using the Pacific Ocean’s vital sealanes for target practice and providing some of the munitions being used against civilians in Europe. Libya, Syria and the other migration crises posed real societal and political challenges for Europe, but nothing like what the continent has been bracing for in the event of either crippling energy shortages or an outright escalation into a military conflict, potentially nuclear conflict, with Russia. China’s growing ambitions and willingness to use force pose direct challenges to the West and its prosperity; American financier Ken Griffin recently made the headlines when he observed that if Chinese military action were to cut off or disrupt American access to Taiwanese semiconductor chips, the immediate impact on the U.S. economy would be between five and 10 per cent of GDP. That would be a Great Depression-sized bodyblow, and it could happen almost instantly and without much warning.

Pondering Van Praagh’s list later on, it occurred to me that the more remote threats to core Western security and economic interests were also more remote in time. The closer Van Praagh’s summation of crises came to the present, the more immediate and near to us they became.

November 24, 2022

Pavlov’s House, codenamed “Lighthouse” in Stalingrad

In The Critic, Jonathan Boff reviews The Lighthouse of Stalingrad: The Hidden Truth at the Centre of WWII’s Greatest Battle by Iain MacGregor:

In the summer of 1942, with the German army deep inside the Soviet Union, Adolf Hitler launched Operation Blue, an attack from around Kharkiv in south-east Ukraine across hundreds of miles of steppe towards the oil fields of the Caucasus. Part of the plan required the German Sixth Army under General Paulus to secure the flank by seizing the industrial city of Stalingrad on the banks of the Volga.

By the middle of September Paulus’s troops were fighting their way, street by street, building by building, and sometimes room by room, through a city reduced to ruins by artillery shelling and the bombs of the Luftwaffe. The fighting was ferocious. Although by November most of Stalingrad was in German hands, several pockets of resistance still held out. Meanwhile, the Red Army was secretly massing for a counter-attack in the open terrain on either side of the city.

On 19 November 1942, General Zhukov unleashed a giant pincer attack which quickly overran the Romanian, Hungarian and Italian forces protecting Paulus’s flanks. Within days the German Sixth Army found itself trapped in a giant pocket, cut off from the rest of the German army. Here, in the depths of a Russian winter, nearly 300,000 surrounded men tried to hold out as their supplies of food, fuel, ammunition and medicine dwindled away.

By the end of January 1943, all hope of relief was gone. To Hitler’s disgust, Paulus ordered the remnants of his army to lay down their weapons. Of the 91,000 German soldiers sent into captivity in Siberia, only 5,000 would survive to ever see their homes again. Immense and terrible as the battle was — we will never know exactly how many troops took part, nor how many died, but it is probable that the total of dead, wounded and captured on both sides reached two million — Stalingrad was not the biggest battle of the war, nor even the bloodiest. Nonetheless, it remains, alongside Dunkirk and D-Day, among the touchstones of the Second World War, largely because it encapsulates three linked but distinct stories. Iain MacGregor does a fine job of covering each in his rich study.

First, Stalingrad was one of the most important battles of the war. It marked the high-water mark of the Nazi invasion of the USSR and an end to Hitler’s genocidal dreams of destroying the Soviet Union. Before Stalingrad, and the other crushing defeats the Axis suffered at around the same time in Tunisia and the Solomon Islands, the initiative had always lain with Germany and Japan. Afterwards, the Allies decided where, when and how the war would be fought.

MacGregor establishes this context neatly. He explains with just the right amount of detail why Operation Blue was launched and what it hoped to achieve. He offers a clear discussion of the decisions taken, and mistakes made, on both sides; and he hints at the logistical weaknesses that probably damned the Germans to disappointment from the start.

The strongest point of this book, however, is its description of the street-fighting in the heart of the city around a building known as “Pavlov’s House” (codename Lighthouse: hence the title of the book). Here the German 71st and Soviet 13th Guards rifle divisions fought for months. By focusing on this small area and these two formations, MacGregor is able to dig deep enough into the tactical detail to give us a clear sense of the difficulty, violence and terror of urban warfare, without swamping us with repetitive detail. His descriptions of fighting have a cinematic quality, swooping smoothly from panoramic tracking shots of the initial German charge down towards the waters of the Volga into close-ups of bullet-riddled mannequins fought over in the ruins of a department store.

November 23, 2022

“What we’re witnessing is, in short, the least expensive generational kneecapping of a geopolitical rival in world history”

Stephen Green on the still ongoing Russo-Ukraine war:

Here’s a hard truth our friends in Kyiv need to remember: Lying isn’t helpful. There are limits to our tolerance.

Here’s another: You’re going to have to make some compromises to end this war because your total victory isn’t in America’s interest here; punishing aggression is. When we decide that Russia has suffered enough, you might find yourselves on your own. Come to the table and negotiate accordingly.

Here is a hard truth for conservative Americans — there are fewer of them than you’d assume from reading Twitter or internet comments sections — opposed to us aiding Ukraine for domestic reasons.

There is no doubt in my mind that much of Ukraine remains what it was: A financial playground for America’s rich elites, and that they have done nothing but increase their ill-gotten gains thanks to our part in keeping Ukraine in the fight. But that’s just one of the many prices we pay for letting our civic structures become so rotten.

The hard truth is, enriching a few corruptocrats is still cheap compared to a continent-wide war in Europe — which is exactly what we risked had we let the Russians march right through.

Here’s a hard truth for my Russian friends and their supporters: The point where Putin & Co. had hoped to aggrandize their country or themselves has long passed. It’s time to ask for a ceasefire and come to the negotiating table.

They know this already, of course, except for the most deluded of true believers. The trick is constructing Sun Tzu’s golden bridge for them to retreat across.

The hard truth I must always keep in mind is that Western leadership, particularly our own, is not up to Sun Tzu’s task.

There is another hard truth that Moscow must come to grips with: Putin threw the dice on an expansionary war but shrank his country’s standing instead.

Russia spent more than a decade modernizing its military. It is becoming increasingly de-modernized with every day of fighting in Ukraine. Destroyed T-80 and T-90 tanks — the most modern in Moscow’s inventory — are being replaced by T-62s that were obsolete 50 years ago. Soldiers in their 20s, casualties of war, are being replaced by ill-trained “mobiks” in their 30s, 40s, and even 50s.

It will take far longer than a decade to replace what Putin has wasted.

The way this war has squandered Russian resources, finances, and demographics has serious geopolitical implications. For a few tens of billions of dollars — admittedly, some of them squandered — our Number Two geopolitical rival has had the heart cut out of its conventional military forces, all without spilling the blood of a single American soldier.

November 20, 2022

A Conspiracy to kill America’s President? – WW2 – 221 – November 19, 1943

World War Two

Published 19 Nov 2022A torpedo attack against the President; a Marine invasion in the central Pacific that turns very bloody in a hurry; German counterattacks in the Soviet Union; a bombing raid in Italy against a secret weapons site — all of that this week.

(more…)

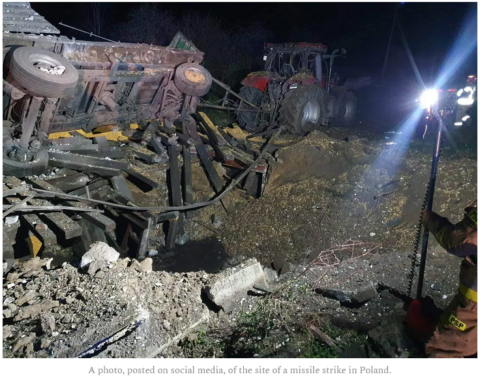

Cold War echoes on the Polish-Ukrainian border

In The Line, what Matt Gurney calls a “surprise fire drill” for a potential nuclear war:

Those with any memory of the Cold War probably got a bit of a cardio workout even if they were sitting still earlier this week when Polish news sources, which were quickly matched by American ones, reported that a Russian missile had landed in Poland, killing two civilians. An armed attack by Russia, in other words, on a NATO member state, even if a likely accidental one — Russia was bombing targets in Ukraine at the time and the site of the Polish blast was quite near the border with its embattled neighbour.

Still. Oops.

It didn’t take long before doubt emerged. At present, the official theory offered by Poland and accepted by NATO is that the missile that killed the two unfortunate Poles was actually a Ukrainian air-defence missile that was fired at incoming Russian missiles in self-defence. It somehow malfunctioned and landed in Poland. The Ukrainians themselves seem unconvinced and there are certainly those wondering if a wayward Ukrainian missile is a cover story to de-escalate a Russian mistake. Personally, I’d guess no. It probably was a Ukrainian missile. And if it is all a cover story in the cause of keeping tension between Moscow and the West at a low-sweat stage, I can live with that, for now.

The point isn’t for me to pretend I’m a munitions expert, capable of instantly solving the case with only the briefest glance at photos of a fragment of twisted missile debris. It’s more to consider what this event felt like, and what it easily could have been: one of the scarier scenarios Western officials and analysts have been worried since this war began nine months ago — accident kicking off a conflict neither side wanted but neither will back down from once it’s begun.

This isn’t a new fear. It was a fear during the Cold War. And a justified one. At several points during that long standoff, technical malfunctions or political miscalculations raised the danger of a nuclear war to horrifying levels. On a few occasions American defense commanders wrongly believed that the Soviets were launching an attack; luckily for everyone, the Americans had redundancies and were well trained and cooler heads always prevailed. In 1983, Soviet satellites reported the Americans were firing ballistic missiles at the Soviet Union. Tensions were high at the time and the Soviets had decided to launch a full strike on the West as soon as any NATO launches were detected. But Lieutenant Colonel Stanislav Petrov, a relatively low-ranked Soviet officer working the night shift, concluded that the warnings were probably a glitch — it didn’t make sense to him that America would open a surprise attack with a handful of missiles instead of the full arsenal. Rather than pass on a warning that would have triggered Soviet launches against NATO, he reported that the launch detections were a technical malfunction in the Soviet equipment. He did that again when further launches were detected. Lt. Col. Petrov then spent a few long and anxious minutes waiting to see if any NATO nuclear weapons exploded over targets in the Soviet Union. Waiting to see what happened was the only way the colonel could know if he’d made the right call, or a very, very bad one.

He was right, of course. It was a glitch. New Soviet satellites were being tricked by sunlight bouncing off clouds at high altitude. But for a few minutes, the fate of the world hung on one mid-ranked Soviet officer’s middle-of-the-night judgment call.

These real-life examples are horrifying. But learning of them never hit me quite as hard as the fictional scenario portrayed in the 1962 film Fail-Safe. Released around the same time as the more famous Doctor Strangelove, Fail-Safe, adapted from the novel Red Alert, was a grimly serious counterpart to Kubrick’s dark comedy. With an all-star cast that includes Walter Matthau and Henry Fonda, Fail-Safe depicts a series of small accidents that result in a group of American bomber pilots concluding that they have been ordered to conduct a retaliatory strike on the Soviet Union. There is no war. It’s entirely a misunderstanding, a fluke of American technological glitches and Soviet jamming. But the American pilots, trained to expect Soviet tricks and lies and to accept no order to abort (as such an order could be faked) relentlessly bore in on their targets, truly believing that they are avenging a Soviet strike on America.

November 16, 2022

The Real Reason for Hitler’s War – WW2 Specials

World War Two

Published 15 Nov 2022The murder of the Jews of Europe is not simply conducted alongside the military and political war aims of the Third Reich. For Hitler and the Nazis, the murder of the Jews of Europe is the military-political aim of the war. It confounds all logic, but in the twisted worldview of Nazi ideology, it makes perfect sense. This is a war on the Jewry.

(more…)