World War Two

Published 23 Sep 2023Monty’s Operation(s) Market Garden, to drop men deep in the German rear in the Netherlands and secure a series of bridges, begins this week, but has serious trouble. In Italy the Allies take Rimini and San Marino, but over in the south seas in Peleliu the Americans have serious problems with Japanese resistance. Finland and the USSR sign an armistice, and in Estonia the Soviets take Tallinn, and there are Soviet plans being made to enter Yugoslavia.

(more…)

September 24, 2023

Operation Market Garden Begins – WW2 – Week 265 – September 23, 1944

September 21, 2023

Iranian Railways, Red Cross Care Packages, and Tail Gunners – WW2 – OOTF 31

World War Two

Published 20 Sept 2023How did the Allies build and manage an enormous railway supplying the Soviet Union through Iran? How did the Red Cross deliver aid parcels through enemy territory to Allied POWs? And, how effective were the rear gunners in ground attack aircraft like the Stuka and Sturmovik? Find out in this episode of Out of the Foxholes.

(more…)

September 17, 2023

The Ballad of Chiang and Vinegar Joe – WW2 – Week 264 – September 16, 1944

World War Two

Published 16 Sep 2023The Japanese attacks in Guangxi worry Joe Stilwell enough that he gets FDR to issue an ultimatum to Chiang Kai-Shek, in France the Allied invasion forces that hit the north and south coasts finally link up, the Warsaw Uprising continues, and the US Marines land on Peleliu and Angaur.

(more…)

September 16, 2023

Is Canada knowingly running a massive educational swindle on poor Indian students?

If even half of what Stephen Punwasi reports here is true, then the Canadian government and higher education ministries in the provinces deserve nothing but abuse:

The thread continues:

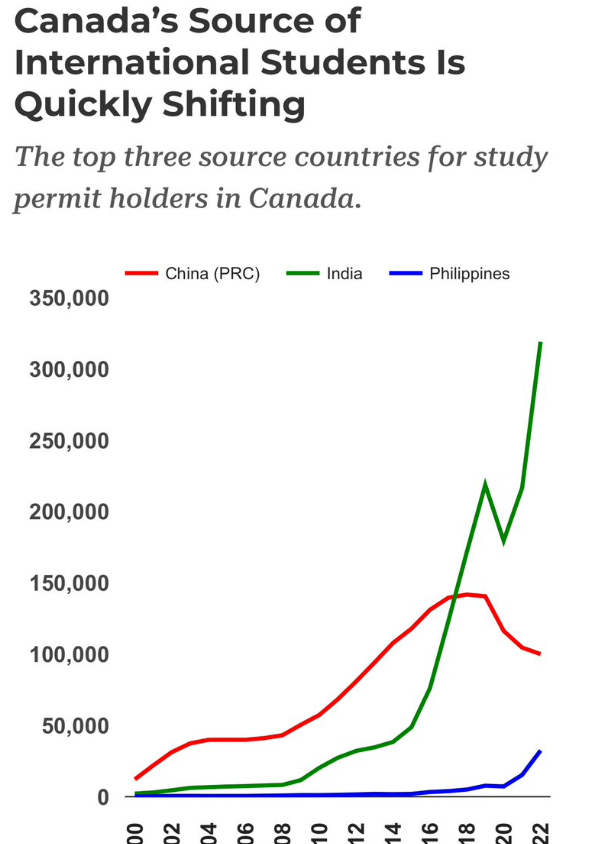

4/ 🇨🇦, addicted to the cash, cooked up a $148m plan to replace those students with new ones—primarily in developing countries.

Permits to students from India spiked fast… strangely fast. Who are these students? Get a spoon to bite, because this is where it gets f*cked.

5/ India is a FAST growing country, forecast to have the world’s largest middle class soon. It has wealthy families, but they aren’t moving here. An Indian university study found most students looking to study in 🇨🇦 are from low-income farming regions & know little about it.

6/ What they “know” is what the recruiter told them: It’s filled with opportunity, automatic PR, guaranteed gov jobs, etc. Sometimes, the recruiters “get them in” to prestigious schools they could never actually get into. All lies—they’ll say anything for the commission.

7/ Recruiters tell these families their kid is brilliant & just in the wrong country. Find a way to pay their education, & all of the parents’ hard work pays off. Bet the farm, like good parents do. So they round up their savings (& sometimes relatives). They take out loans.

8/ Heck, some literally bet the farm. Oh, some recruiters know people that specialize in high interest loans secured by your farm? Super convenient. Oh, they have a secure stream of capital, a lot of it from investors in 🇨🇦? So lucky, what are the odds‽

9/ So the kids get to 🇨🇦 & don’t arrive at UBC or U of T, but a private career college in a strip mall. Sometimes not even the school they applied to. Some schools popped up almost overnight, others don’t have classes some semesters, & some have no domestic students.

10/ Some are run by swell folks who are strangely close with alleged organized crime groups. Opportunity is everywhere! Anyway, once you’re registered—you can start vouching for visas, there’s no limit. 🇨🇦 wanted this, after all.

11/ So they:

– spent $50k to go to a diploma mill;

– don’t speak english, because of testing fraud;

– have no money;

– often rent mattresses, taking 8/hr shifts w/other students;

– if this doesn’t work, their parents lose everythingA TO funeral home sends 5 dead back per month.

12/ Don’t worry. 🇨🇦 will help, right? In 2022, it lifted the restriction of 20 hours of on-campus work, to “help” 🇨🇦 solve its low-wage labor crisis. Those viral videos of hundreds of people waiting in line for a low-wage job interview? Those are mostly international students.

13/ To reiterate, 🇨🇦 scoured the world for poor families. Promised opportunity if they risked everything. It turns out there was no opportunity, so now they’re stuck paying off debt while most of their income is consumed by shelter costs. It sounds familiar, but why evades me

14/ but here’s the kicker. Other countries where this scam was brewing signed an inter-country agreement to refuse unethical student visa brokering. Did 🇨🇦? Nope, it actively rejected it. Once again, because this is a part of its strategy.

France’s Vietnam War: Fighting Ho Chi Minh before the US

Real Time History

Published 15 Sept 2023After the Second World War multiple French colonies were pushing towards independence, among them Indochina. The Viet Minh movement under Ho Chi Minh was clashing with French aspirations to save their crumbling Empire.

(more…)

September 15, 2023

Learning to handle mules to accompany Chindit columns in WW2

Robert Lyman posted some interesting details from veteran Philip Brownless of how British troops in India had to learn how to handle mules and abandon their motor transport in order to get Chindit columns into Japanese territory in Burma:

Soon after our return from the Arakan front in the autumn of 1943, we were in central India, and had been told that the whole division was to be handed over to General Wingate and trained to operate behind the Japanese lines. All our motor transport was to be taken away and we were to be entirely dependent upon mules for our transport.

The C.O. one evening looked round the mess and then said to me “You look more like a country bumpkin than anybody else. You will go on a veterinary course on Tuesday and when you come back you will take charge of 44 Column’s mules.”

I had never met one of these creatures before. On arriving at Ambala I reported to the Area Brigade Major who wasn’t expecting me and seemed to have no clue about anything. He said “You’d better go down to the Club and book in”. I reported to the Club, a comfortable looking establishment, and they seemed to have a vague idea that a few bodies like me might turn up on a course and were apologetic that I would have to sleep in a tent but otherwise could enjoy the full facilities of the Club. I was shown the tent, an EPIP tent or minor marquee, with a coloured red lining and golden fleur de lys all over it, (very Victorian) with a small office extension with table and chair in front and another extension at the back with bath, towel rail and a fully bricked floor. Having lived either in a tent or under the stars in both the desert and the Arakan for the last 2 years, this struck me as luxury indeed. Even better, I took on a magnificent bearer, with suitable references, whom I found later was some kind of Hindu priest. I soon got used to having my trouser legs held up for me to put my feet in, and being helped into the rest of my clothes. I had a comfortable 3 weeks learning all about mules.

I discovered all sorts of things like the veterinary term “balls”, which were massive pills which were given to the mule by – first of all grabbing his tongue and pulling it out sideways so he couldn’t shut his mouth on your arm, and then gently throwing the ball at his epiglottis and making sure it went down. Then you let go of his tongue and gave him a nice pat. One of our lecturers, an Indian warrant officer, knew his stuff well and was so pleased about it that when he asked a question he would give you the answer himself. He liked being dramatic and loved to finish a description of some fatal ailment by saying “Treatment, bullet”.

Many of the men in our battalion were East Enders; others came from all over Essex. A few were countrymen, two were Irish and knew all about horses, one sergeant had been in animal transport and one invaluable soldier had been an East End horse dealer. The large majority had had nothing to do with animals: however, the saving grace was that English soldiers seem to be naturally good with animals and soon learned to handle them well. I arranged to get some instruction from the nearby unit of Madras Sappers and Miners and we borrowed a handful of trained mules from them for the men to practise handling, tying on loads and learning to talk to them.

Then came the great day when we were to draw up our main complement of animals, about 70 mules and 12 ponies. We were dumped at a small railway station. It was all open ground and there was a team of Army Veterinary Surgeons to allocate fairly between the three battalions, the Essex, the Borders and the Duke of Wellington’s. Lieut. Jimmy Watt of the Borders was a pal of mine: he and I, with a squad of men were to march them back nearly 100 miles to our camp, sleeping each of the five nights under the stars. As soon as we arrived at the disembarkation site I got all our mule lines laid out, with shackles (used to tie mules fore and aft) and nosebags ready. I had also picked up the tip that the mules would be wild, having spent three days in the train, and almost impossible to hold, so I instructed our men to tie them together in threes before they got off the train. As all three pulled in different directions, one muleteer could hold them. Not everybody had learned this trick so the result was that wild mules were careering all over the place, impossible to catch. When our first handful of mules arrived, they were quickly secured in a straight line and fed. They were familiar with lines like this and cooled down at once, long ears relaxed and tails swishing amiably. When the wild mules careering round saw this line, they said to themselves “We’ve done this before” and came and stood in our lines. We shackled them and I picked out the moth-eaten ones and sent them back to the vets who kept sending polite messages of thanks to Mr. Brownless for catching them. We finished up with a very good set of mules. Jimmy Watt and I had a bit of a conscience about the Duke of Wellington’s so we picked them out a really good pony. We felt even worse a few weeks later when it was sent back to Remounts with a weak heart! The Brigade Transport Officer visited us the second evening so Jimmy Watt and I walked him round rather quickly, chatting hard, to approve the allocation of animals, and he agreed with our arrangement.

In a highly optimistic mood early on, I decided to practise a river crossing. We marched several miles out from camp to a typical wide sandy Indian river, 300 yards across, made our preparations, i.e. assembling the two assault boats, making floating bundles of our clothes and gear by wrapping them in groundsheets, unsaddling the animals, and assembling at the water’s edge. A good sized detachment of muleteers was posted on the opposite bank ready to catch the mules. The mules waded into the shallow water but no one could get them to move off. We tried all sorts of inducements in vain and then suddenly, one sturdy little grey animal decided to swim and the whole lot immediately followed. Calamity ensued! Mules are very short sighted and could only dimly see the opposite bank but downstream was a bright yellow sandy outcrop and they all made for this. The muleteers on the other bank, when they realised what was happening, ran through the scrub and jungle as fast as they could, but the mules arrived first and bolted off into the wilds of India. I swam my pony across with my arm across his withers and directing him by holding his head harness, the gear was ferried across and the mule platoon, with one pony, began the march back to camp. Deeply depressed, I wondered how to tell the C.O. I had lost all his mules and imagined the court martial which awaited me (or, serving under General Wingate, would I be shot out of hand?) An hour and a half later we came in sight of the camp and to my utter astonishment I could see the mules in their lines. When I arrived at the mule lines, the storeman met me and said that the whole lot had arrived at the double and had gone to their places. He had merely gone along the lines, shackling them and patted their noses. Salvation! I kept quiet for a bit but it got out and I was the butt of much merrymaking.

September 13, 2023

At the end of the Axis’ Destiny – War Against Humanity 114

World War Two

Published 12 Sep 2023The imperial dreams of Germany and Japan are in tatters. But the expansionist beasts do their best to drag their enemies down with them. Across Europe the cycle of resistance and retaliation continues. Paris is free but Warsaw burns. V-1s rain down on innocent civilians in London. The Japanese cleanse West Borneo of opposition. The genocide of the Jews continues. For so many people, liberation is now so near yet so far away.

(more…)

September 12, 2023

Justin Trudeau should just stay away from India … it’s an ill-omened place for him

Paul Wells on the latest subcontinental pratfall of Prime Minister Look-At-My-Socks:

Later, word came from India that Justin Trudeau’s airplane had malfunctioned, stranding him, one hopes only briefly. It’s always a drag when a politician’s vehicle turns into a metaphor so obvious it begs to go right into the headline. As for the cause of the breakdown, I’m no mechanic, but I’m gonna bet $20 on “The gods decided to smite Trudeau for hubris”. Here’s what the PM tweeted or xeeted before things started falling off his ride home:

One can imagine the other world leaders’ glee whenever this guy shows up. “Oh, it’s Justin Trudeau, here to push for greater ambition!” Shall we peer into their briefing binders? Let’s look at Canada’s performance on every single issue Trudeau mentions, in order.

On climate change, Canada ranks 58th of 63 jurisdictions in the global Climate Change Performance Index. The country page for Canada uses the words “very low” three times in the first two sentences.

On gender equality, the World Economic Forum (!) ranks Canada 30th behind a bunch of other G-20 members.

On global health, this article in Britain’s BMJ journal calls Canada “a high income country that frames itself as a global health leader yet became one of the most prominent hoarders of the limited global covid-19 vaccine supply”.

On inclusive growth, the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development has a composite indicator called the Inclusive Growth Index. Canada’s value is 64.1, just behind the United States (!) and Australia, further behind most of Europe, stomped by Norway at 76.9%.

On support for Ukraine, the German Kiel Institute think tank ranks Canada fifth in the world, and third as a share of GDP, for financial support; and 8th in the world, or 21st as a share of GDP, for military support.

Almost all of these results are easy enough to understand. A small number are quite honourable. But none reads to me as any kind of license to wander around, administering lessons to other countries. I just finished reading John Williams’ luminous 1965 novel about university life, Stoner. A minor character in the book mocks the lectures and his fellow students, and eventually stands unmasked as a poser who hasn’t done even the basic reading in his discipline. I found the character strangely familiar. You’d think that after nearly a decade in power, after the fiascos of the UN Security Council bid, the first India trip, the collegiate attempt to impress a schoolgirl with fake trees, the prime minister would have figured out that fewer and fewer people, at home or abroad, are persuaded by his talk.

But this is part of the Liberals’ problem, isn’t it. They still think their moves work. They keep announcing stuff — Digital adoption program! Growth fund! Investment tax credits! Indo-Pacific strategy! Special rapporteur! — and telling themselves Canadians would miss this stuff if it went away. Whereas it’s closer to the truth to say we can’t miss it because its effect was imperceptible when it showed up.

In a moment I’ve mentioned before because it fascinates me, the Liberals called their play a year ago, as soon as they knew they’d be facing Pierre Poilievre. “We are going to see two competing visions,” Randy Boissonault said in reply to Poilievre’s first Question Period question as the Conservative leader. The events of the parliamentary year would spontaneously construct a massive contrast ad. It was the oldest play in the book, first articulated by Pierre Trudeau’s staff 50 years ago: Don’t compare me to the almighty, compare me to the alternative. It doesn’t work as well if people decide they prefer the alternative. It really doesn’t work if the team running the play think it means, “We’re the almighty”.

September 10, 2023

Bulgaria at War with Everyone – WW2 – Week 263 – September 9, 1944

World War Two

Published 9 Sep 2023This week the USSR invades Bulgaria … who’ve also declared war on Germany, and who are still at war with the US and Britain, so Bulgaria is briefly technically at war with all four at once. Finland signs a ceasefire, the Germans are pulling out of Greece, the Warsaw and Slovak Uprisings continue, Belgium is mostly liberated, and across the world, the Japanese enter Guangxi, and there are American plans to liberate the Philippines.

(more…)

QotD: The hill people and the valley people

There’s a clichéd history of civilization which goes something like: once upon a time all human beings lived in wandering hunter-gatherer bands where everybody was directly involved in food production. Then while sojourning through a fertile river valley, some of these groups discovered agriculture. The relative predictability and reliability of farming, coupled with the much higher caloric yield per hour of labor,1 made it possible to support a denser population, and for only a portion of it to be directly involved in food production. The rest of them could become soldiers, artisans, priests, and scribes. They could develop technology, pass on their knowledge through writing, and develop complex systems of taxation, bureaucracy, and forced labour. Along the way, they made picturesque little walled farming villages […]

This is not their story. Instead it’s the story of the people who live in the hills behind that village. Without knowing anything at all about the place that picture depicts, you can probably tell me a lot about the people in those hills. Hill people are hill people, the world over. What are the odds that they’re clannish? Xenophobic? Backwards! Unusual family structures. Economically immiserated (probably due to their own paranoia and indolence). Deviant in their religious, commercial, and sexual practices. Illiterate, or at best poorly-read. They also probably talk funny. Basically they’re barbarians, but not the impressive kind who ride out of the steppe to massacre and enslave the soft city-dwellers. No, something more like living fossils — our ancestors were once like that, but then they got with the program. Well if they could do it, why don’t those hill dwellers move down here too, like normal people?2 They’re up to no good up there.

That’s certainly been the traditional view from the valleys, and there’s some truth to it, but there’s one important detail that we valley-dwellers get wrong. Far from being aboriginal holdovers of some previous phase of humanity, it’s relatively easy to determine from genetic, linguistic, and archaeological evidence that the hill people are largely descended from … the valley people!3 But … that would mean that there are people who look around at our beautiful civilization and reject its fruits — you know, art, technology, fusion cuisine, and uh … taxation, conscription, epidemic disease, corvée labour … How dare they!

You would never know it from reading the reports of the valley-bureaucrats, but the great agricultural civilizations of classical antiquity were in a near-constant state of panic over people wandering away from their farms and becoming barbarians.4 There are estimates that over the course of the empire something like twenty-five percent of the inhabitants of Roman border provinces quietly slipped across the limes for the proud life of the savage. In Ancient China, the movement was more cyclical — in times of war, or epidemic, or famine, entire villages might give up rice agriculture and vanish into the hills. Then, when the situation had stabilized, the human tide would reverse, and the hills would disgorge barbarians eager to be Sinicized (or really re-Sinicized, as their parents and grandparents had been). In both these cases and more, the boundary between “civilized” and “savage” was a great deal more porous, and the flow a great deal more bi-directional than we might realize. Like a single substance in two phases, now boiling, now condensing, changing back and forth in response to changes in the temperature.

So why then is it that hill people5 the world over have so much in common? Scott argues pretty convincingly that something like convergent cultural evolution for ungovernability is at work — that is, the qualities we stereotypically associate with backwards and barbarous peoples are precisely the traits that make one difficult to administer and tax. Some examples of this are very obvious to see — for instance physical dispersal in difficult terrain makes it harder to be surveilled, measured, or conscripted. Scott also talks a lot about the crops that hill people like to grow, and how the world over they tend to be either crops that are amenable to swiddening and don’t require irrigation, or things like tubers that mature underground and can be harvested at irregular times. Both patterns make it easy to lie about how much food you’ve planted and where, hence difficult for others to tax or control you.

What about illiteracy? Scott finds that many hill people around the world have oral legends about how they once had writing, but no longer do. Of course this is exactly what we would expect if, contrary to the usual story, the hill people are not the ancestors of the valley people, but their descendants. Yet the question remains, why give up writing? Scott posits several benefits of illiteracy: one is just that the inability to write removes any temptation to keep written records of anything, and written records are the kind of thing that can be used against you by a tax collector or an army recruiter.

But more fundamentally, a reliance on oral history and genealogy and legend is powerful precisely because these things are mutable and can be changed according to political convenience. Anybody who’s read ancient Chinese accounts of the steppe peoples or Roman discussions of Germanic barbarians has probably recoiled from the confusing profusion of tribes, peoples, and nations; the same ethnonyms popping in and out of existence over a vast area, or referring to a band of a few hundred one year and a nation of millions a decade later. Scott argues that the reason we see this is that the very notion of stable ethnic identity is a fundamentally “valley” conceit. Out in the hills or on the far wild plains, people exist in more of a quantum superposition of identities, and the nonsensical patterns you see in the histories come from imperial ethnographers feverishly making classical measurements in a double-slit experiment and trying to jam the results into a sensible form.

John Psmith, “REVIEW: The Art of Not Being Governed by James C. Scott”, Mr. and Mrs. Psmith’s Bookshelf, 2023-01-16.

1. Scott has yet another book about how this important detail of the stock story is totally false. In Scott’s telling, early agriculture produced fewer calories per hour of work than hunting and foraging. The entire increase in social complexity associated with primitive agriculture came not from a food surplus, but from the fact that it was easier to measure how much food everybody was producing and confiscate a portion of it.

2. Maybe then one of their descendants can go to Yale Law School and write a book about it.

3. Next time you’re driving through Montana, try to count how many people are transplants from New York or California.

4. Once you know this fact, you can go back and read those classical texts esoterically, and nervous panic over people defecting from civilization is practically all you will see.

5. I’ve used “hill people” throughout this review as a synecdoche for groups that have rejected a life-pattern involving settled agriculture and tax-paying, but as Scott points out there are many kind of terrain unsuitable or difficult for state administration. Marshes have historically been another magnet for those rejecting polite society, as have deserts and open plains.

September 4, 2023

QotD: Historical rice farming versus wheat or barley farming

Because rice is such a different crop than wheat or barley, there are a lot of differences in the way that rice cultivation shapes the countryside. […] The thing to note about rice is that it is both much more productive on a per-acre basis than wheat or barley, but also much more labor intensive; it also relies on different forms of capital to be productive. Whole-grain wheat and brown rice have similar calorie and nutritional value (brown rice is somewhat better in most categories) on a unit-weight basis (so, per pound or ton), but the yield difference is fairly large: rice is typically around (very roughly) 50% more productive per acre than wheat. Moreover, rice plants have a more favorable ratio of seeds-to-plants, meaning that the demand to put away seeds for the next harvest is easier – whereas crop-to-seed ratios on pre-modern wheat range from 3:1 to 10:1, rice can achieve figures as high as 100:1. As a result, not only is the gross yield higher (that is, more tons of seed per field) but a lower percentage of that seed has to be saved for the next planting.

At the same time, the irrigation demands for effective production of wet-rice requires a lot of labor to build and maintain. Fields need to be flooded and drained; in some cases (particularly pre-modern terrace farming) this may involve moving the water manually, in buckets, from lower fields to higher ones. Irrigation canals connecting paddies can make this job somewhat easier, as can bucket-lifts, but that still demands moving quite a lot of water. In any irrigation system, the bunds need to be maintained and the water level carefully controlled, with also involves potentially quite a lot of labor.

The consequence of all of this is that while the rice farming household seems to be roughly the same size as the wheat-farming household (that is, an extended family unit of variable size, but typically around 8 or so members), the farm is much smaller, with common household farm sizes, even in the modern period, clustering around 1 hectare (2.47 acres) in comparison to the standard household wheat farms clustered around 4-6 acres (which, you may note with the yield figures above, lands us right back at around the same subsistence standard).

Moreover, rice cultivation is less soil dependent (but more water dependent) because wet-rice farming both encourages nitrogen fixation in the soil (maintaining the fertility of it generally without expensive manure use) and because rice farming leads naturally to a process known as pozdolisation, slowly converting the underlying soil over a few years to a set of characteristics which are more favorable for more rice cultivation. So whereas with wheat cultivation, where you often have clumps of marginal land (soil that is too wet, too dry, too rocky, too acidic, too uneven, too heavily forested, and so on), rice cultivation tends to be able to make use of almost any land where there is sufficient water (although terracing may be needed to level out the land). The reliance on the rice itself to “terraform” its own fields does mean that new rice fields tended to under-produce for the first few years.

The result of this, so far as I can tell, is that in well-watered areas, like much of South China, the human landscape that is created by pre-modern rice cultivation is both more dense and more uniform in its density; large zones of very dense rice cultivation rather than pockets of villages separated by sparsely inhabited forests or pasture. Indeed, pasture in particular seems in most cases almost entirely pushed out by rice cultivation. That has very significant implications for warfare and I have to admit that in reading about rice farming for this post, I had one of those “oh!” moments of sudden understanding – in this case, how armies in pre-modern China could be so large and achieve such massive local concentrations. But as we’ve discussed, the size of an army is mainly constrained by logistics and the key factor here is the ability to forage food locally, which is in turn a product of local population density. If you effectively double (or more!) the population density, the maximum size of a local army also dramatically increases (and at the same time, a society which is even more concentrated around rivers is also likelier to allow for riverine logistics, which further improves the logistical situation for mass armies).

But it also goes to the difficulty many Chinese states experienced in maintaining large and effective cavalry arms without becoming reliant on Steppe peoples for horses. Unlike Europe or the Near East, where there are spots of good horse country here and there, often less suited to intensive wheat cultivation, most horse-pasturage in the rice-farming zone could have – and was – turned over to far more productive rice cultivation. Indeed, rice cultivation seems to have been so productive and suitable to a sufficient range of lands that it could push out a lot of other kinds of land-use, somewhat flattening the “ideal city” model that assumed wheat and barley cultivation.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Bread, How Did They Make It? Addendum: Rice!”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2020-09-04.

September 3, 2023

The War is Five Years Old – WW2 – Week 262 – September 2, 1944

World War Two

Published 2 Sep 2023Five years of war and no real end in sight, though the Allies sure seem to have the upper hand at the moment. Romania is coming under the Soviet thumb and Red Army troops are at Bulgaria’s borders, the Allies enter Belgium and also take ports in the south of France. A Slovak National Uprising begins against the Germans, and the Warsaw Uprising against them continues, but in China it is plans for defense being made against the advancing Japanese.

(more…)

“This is the world of the Spring and Autumn Annals, and the Zuozhuan“

Another anonymous book review at Scott Alexander’s Astral Codex Ten considers the Zuozhuan, a commentary and elaboration of the more bare-bones historical record of the Spring and Autumn Annals:

To tell the story of the fall of a realm, it’s best to start with its rise.

More than three thousand years ago, the Shang dynasty ruled the Chinese heartland. They raised a sprawling capital out of the yellow plains, and cast magnificent ritual vessels from bronze. One of the criteria of civilization is writing, and they had the first Chinese writing, incising questions on turtle shells and ox scapulae, applying a heated rod, and reading the response of the spirits in the pattern of cracks. “This year will Shang receive good harvest?” “Is the sick stomach due to ancestral harm?” “Offer three hundred Qiang prisoners to [the deceased] Father Ding?” The kings of Shang maintained a hegemony over their neighbors through military prowess, and sacrificed war captives from their campaigns totaling in the tens of thousands for the favor of their ancestors.

But the Shang faced growing threat from the Zhou, a once-subordinate people from west beyond the mountains. Inspired by a rare conjunction of the planets in 1059 BC, the Zhou declared that there was such a thing as the Mandate of Heaven, a divine right to rule—and while the Shang had once held it, their misrule and immorality had forced the Mandate to pass to the Zhou. Thirteen years later, the Zhou and their allies defeated the Shang in battle, seized their capital, drove their king to suicide, and supplanted them as overlords of the Central Plains.

If the Shang were goth jocks, the Zhou were prep nerds. In grave goods, food-serving vessels replaced wine vessels. Mass human sacrifice disappeared, while bureaucracy expanded. The Shang lacked the state power to administer their surrounding subject peoples so much as intimidate them into line; the Zhou, galvanized by a rebellion not long after the conquest, put serious thought into consolidating their control. While the king remained in the west to rule over the original Zhou lands, he sent relatives and allies east into the conquered territories to establish colonies at strategically important locations, anchoring Zhou rule in a sprawling network of hereditary regional lords bound together by blood, marriage, custom, and ancestor worship of the Heaven-blessed founding Zhou kings.

For generations, the system worked, ensuring military successes at the borders and stability in the interior. The first reigns of the dynasty became a golden age in the cultural imagination for thousands of years. But by the dynasty’s second century, barbarian incursions were putting the state on the defensive, and surviving records hint at waning control over the regional lords and power struggles at court. 771 BC marked a breaking point, when barbarians allied with disgruntled nobles to overrun the royal domain and kill King You of Zhou.

Legend has it that the king was bewitched by his new consort, a melancholy beauty born from a virgin impregnated by the touch of a black salamander. Desperate to make her laugh, the king pranked his lords by lighting the beacon fires intended to summon them in case of invasion. When she delighted at the sight, he kept playing the same trick until the lords got sick of him and stopped coming, which doomed him when the barbarians actually invaded.

But the historical reality seems to be the usual sordid political struggle around a new consort — and heir — threatening the power of the old one. The original queen’s powerful father allied with barbarians to root out the upstart, only to get maybe more than he bargained for. Sure, he put his grandkid on the throne in the end, but the royal house had been devastated. It would never regain the ancestral lands it had lost to the barbarians, the direct holdings that filled its treasury and provided for its armies. The king retreated east into the Central Plains, playing ground of lords that were now more powerful than him. While the royal line remained symbolically important, as holder of the Mandate of Heaven from which all the states derived their legitimacy, the loss of central authority in every other sense would unleash centuries of intensifying interstate warfare and upheaval.

This is the world of the Spring and Autumn Annals, and the Zuozhuan.

The Spring

“Spring and Autumn Annals” is a bit of a redundant translation, since “spring and autumn” was just an old way of saying “year”, and thus, “annals”. And technically, there were multiple Spring and Autumn Annals — every state kept, in addition to court and administrative documents, its own laconic record of each year’s wars, diplomacy, natural phenomena, major rites, and notable deaths. But the state of Lu’s is special, because Confucius was from Lu. He’s said to have personally edited and compiled the extant version of its 242-year-long Spring and Autumn, loading each character with weighty yet subtle moral deliberation. This ensured it a place in the Confucian canon, and its survival where every other state’s annals have been lost to time. The era that it covers is named the Spring and Autumn period after the text, not the other way around.

Taken on its own, though, the Annals is little more than a list of dry facts. For example, the first year reads:

The first year, spring, the royal first month.

In the third month, our lord and Zhu Yifu swore a covenant at Mie.

In summer, in the fifth month, the Liege of Zheng overcame Duan at Yan.

In autumn, in the seventh month, the Heaven-appointed king sent his steward Xuan to us to present the funeral equipment for Lord Hui and Zhong Zi.

In the ninth month, we swore a covenant with a Song leader at Su.

In winter, in the twelfth month, the Zhai Liege came.

Gongzi Yishi died.

Who is Zhu Yifu? Who’s Duan? What’s all this about “overcoming”? Where does the moral deliberation come in? This canon badly needs meta, and the most notable of the ancient commentaries written for the Spring and Autumn Annals is the Zuozhuan. Ten times as long as the text it’s for, the Zuozhuan is the flesh on the Annals‘ bare bones, one of the foundational works of ancient Chinese literature and history-writing in its own right.

While tradition attributes the text’s authorship to Zuo Qiuming, a contemporary of Confucius, most modern historians date its compilation to the century after. In its extant form, it’s presented interleaved with the Annals, so that after the Annals’ account of each year, with entries such as …

In summer, in the sixth month, on the yiyou day (26), Gongzi Guisheng of Zheng assassinated his ruler, Yi.

… you have the Zuozhuan’s account of the year, mostly composed of elaborations upon the above entries, such as:

The leaders of Chu presented a large turtle to Lord Ling of Zheng. Gongzi Song and Gongzi Guisheng were about to have an audience with the lord. Gongzi Song’s index finger moved involuntarily. He showed it to Gongzi Guisheng and said, “On other days when my finger did this, I always without fail got to taste something extraordinary.” As they entered, the cook was about to take the turtle apart. They looked at each other and smiled. The lord asked why, and Gongzi Guisheng told him. When the lord had the high officers partake of the turtle, he called Gongzi Song forward but did not give him any. Furious, Gongzi Song dipped his finger into the cauldron, tasted the turtle, and left. The lord was so enraged that he wanted to kill Gongzi Song. Gongzi Song plotted with Gongzi Guisheng to act first. Gongzi Guisheng said, “Even with an aging domestic animal, one is reluctant to kill it. How much more so then with the ruler?” Gongzi Song turned things around and slandered Gongzi Guisheng. Gongzi Guisheng became fearful and complied with him. In the summer, they assassinated Lord Ling.

The text says, “Gongzi Guisheng of Zheng assassinated his ruler, Yi”: this is because he fell short in weighing the odds. The noble man said, “To be benevolent without martial valor is to achieve nothing.” In all cases when a ruler is assassinated, naming the ruler [with his personal name rather than his title] means that he violated the way of rulership; naming the subject means that the blame lies with him.

There’s a few too many mythological creatures and just-so stories for the Zuozhuan to be taken entirely at face value, but it’s clear that its creator(s) had access to diverse now-lost records for the era portrayed. For example, some of the events show a two-month dating discrepancy — one of the states used a different calendar, and most likely the creator(s) overlooked the difference when borrowing from sources from that state. While the overall level of historical rigor versus 4th century BC authorial invention remains under heated debate, the Zuozhuan is undeniably the most comprehensive written source on its era that we have.

And importantly, it’s enjoyable.

You can think of the Zuozhuan as the Gene Wolfe of ancient historical works. It’s not an easy read, especially in translation, where names that are visibly distinct in the original (e.g. 季, 急, 姬, etc.) all get unhelpfully collapsed into one transliteration (Ji). The work drops you into a whirl of nouns and events, some of them one-off asides, others part of long-running narrative threads that might only surface again decades of entries later. While a casual readthrough still offers plenty of rewards, putting together all the subtext, references, and connections between entries is an endeavor that’s occupied readers for millennia. Your unreliable narrator remains enigmatic on most of the events he presents, leaving interpretation as an exercise for the reader; when he does speak, either directly or in the voice of the “noble man”, he can raise more questions than he answers. For one, the rule about the naming of an assassinated ruler largely holds in the Annals, but seems to have some notable exceptions.

But if you’re willing to plunge in, the work offers an experience unlike anything else.

September 2, 2023

QotD: Ancient DNA

… you know I’m always up for the humiliation of a dominant scientific paradigm. I especially like examples where that paradigm in its heyday replaced some much older and unfashionable view that we now know to be correct. It’s important to remind people that knowledge gets lost and buried in addition to being discovered.

The wonderful thing about ancient DNA is it gives us an extreme case of this. Basically, the first serious attempt at creating a scientific field of archaeology was done by 19th century Germans, and they looked around and dug some stuff up and concluded that the prehistoric world looked like the world of Conan the Barbarian: lots of “population replacement”, which is a euphemism for genocide and/or systematic slavery and mass rape. This 19th century German theory then became popular with some 20th century Germans who … uh … made the whole thing fall out of fashion by trying to put it into practice.

After those 20th century Germans were squashed, any ideas they were even tangentially associated with them became very unfashionable, and so there was a scientific revolution in archaeology! I’m sure this was just crazy timing, and actually everybody rationally sat down and reexamined the evidence and came to the conclusion that the disgraced theory was wrong (lol, lmao). Whatever the case, the new view was that the prehistoric world was incredibly peaceful, and everybody was peacefully trading with one another, and this thing where sometimes in a geological stratum one kind of house totally disappears and is replaced by a different kind of house is just that everybody decided at once that the other kind of house was cooler. The high-water mark of this revisionist paradigm even had people saying that the Vikings were mostly peaceful traders who sailed around respecting the non-aggression principle.

And then people started sequencing ancient DNA and … it turns out the bad old 19th century Germans were correct about pretty much everything. The genetic record is one of whole peoples frequently disappearing or, even more commonly, all of the men disappearing and other men carrying off the dead men’s female relatives. There are some exceptions to this, but by and large the old theory wins.

I used to have a Bulgarian coworker, and I asked him one day how things were going in Bulgaria. He replied in that morose Slavic way with a long, sad disquisition about how the Bulgarian race was in its twilight, their land was being colonized by others, their sons and daughters flying off to strange lands and mixing their blood with that of alien peoples. I felt awkward at this point, and stammered something about that being very sad, at which point he came alive and declared: “it is not sad, it is not special, it is the Way Of The World”. He then launched into a lecture about how the Bulgarians weren’t even native to their land, but had been bribed into moving there by the Byzantines who used them as a blunt instrument to exterminate some other unruly tribes that were causing them trouble. “History is all the same,” he concluded, “we invaded and took their land, and now others invade us and take our land, it is the Way Of The World.”

Even a cursory study of history shows that my Bulgarian friend was correct about the Way Of The World. There’s a kind of guilty white liberal who believes that European colonization and enslavement of others is some unique historical horror, a view that has now graduated into official state ideology in America. But that belief is just a weird sort of inverted narcissism. I guess pretending white people are uniquely bad at least makes them feel special, but white people are not special. Mass migration, colonization, population replacement, genocide, and slavery are the Way Of The World, and ancient DNA teaches us that it’s been the Way Of The World far longer than writing or agriculture have existed. It wasn’t civilization that corrupted us, there are no noble savages, “history is all the same”, an infinite history of blood.

Land acknowledgments always struck me as especially funny and stupid: like you really think those people were the first ones there? What about acknowledging the people that they stole it from? Sure enough one of the coolest parts of Reich’s book is his recounting the discovery that there were probably unrelated peoples in the Americas before the ancestors of the American Indians arrived here, and that a tiny remnant of them might even remain deep in Amazonia. So: what does it actually mean to be “indigenous”? Is anybody anywhere actually “indigenous”?

Jane Psmith and John Psmith, “JOINT REVIEW: Who We Are and How We Got Here, by David Reich”, Mr. and Mrs. Psmith’s Bookshelf, 2023-05-29.

August 27, 2023

6 Strange Facts About the Cold War

Decades

Published 27 Jul 2022Welcome to our history channel, run by those with a real passion for history & that’s about it. In today’s video, we will be exploring 6 odd Cold War facts.

(more…)