TimeGhost History

Published 23 Mar 2025In 1947, the British divide the Raj into two nations, India and Pakistan, triggering one of the deadliest mass migrations in history. Sectarian violence between Hindus, Sikhs, and Muslims leaves at least 200,000 dead and displaces millions more. Hastily drawn borders turn neighbours into enemies. The partition’s bloody legacy will lead to decades of tension, war, and bloodshed.

(more…)

March 29, 2025

Why India and Pakistan Hate Each Other – W2W 015 – 1947 Q3

March 27, 2025

Ban the swastika? Are you some kind of racist?

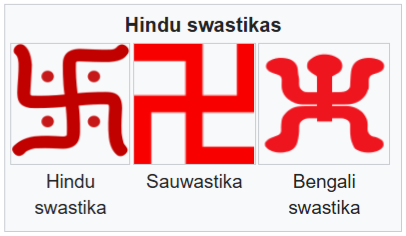

In Ontario, the elected council for the Region of Durham has been reacting to a few painted swastika graffiti around the region over the last couple of months. To, as a politician might say, “send a message”, they proposed banning the use of the swastika altogether … failing to remember that it’s not just neo-Nazi wannabes who use it:

Durham council is adjusting the wording of its calls for a national ban on the Nazi swastika, or “Hakenkreuz“.

This follows efforts by religious advocates to distance their own symbols from the genocidal German fascist regime.

Swastikas often appear in Jain, Hindu and Buddhist iconography.

“The word ‘swastika’ means ‘well-being of all’,” explained Vijay Jain, president of Vishwa Jain Sangathan Canada, at Wednesday’s regional council meeting. “It’s a very sacred word. […] We use it extensively in our prayers.”

“Many Jain and Hindi parents give their children the name ‘Swastika’,” he added. “Many Hindi and Jain people, they keep their [business’s] name as ‘Swastika’. If you go to India, you’ll find the ‘Swastika’ name prominently used.”

“We stand in solidarity with the Jewish community and fully support all of the efforts by authorities to address growing antisemitism in Canada,” he said.

Regional council made its initial call for a ban on Nazi swastikas in February, after two separate incidents of the antisemitic symbol being scrawled inside a washroom at the downtown Whitby library.

On Wednesday, councillors voted to revise that motion to replace the word “swastika” with the term “Nazi symbols of hate”.

B’nai Brith Canada has been spearheading a petition campaign to have the Nazi symbol banned across the country.

The group has increasingly opted to refer to it by the alternative names “Nazi Hooked Cross” or “Hakenkreuz“.

On March 20, B’nai Brith put out a joint statement with Vishwa Jain Sangathan and other religious advocacy groups, calling for further differentiation between the symbols.

“These faiths’ sacred symbol (the Swastika) has been wrongfully associated with the Nazi Reich,” wrote Richard Robertson, B’nai Brith Canada’s Director of Research and Advocacy. “We must not allow the continued conflation of this symbol of peace with an icon of hate.”

March 8, 2025

March 6, 2025

The Iron Curtain Descends – W2W 10 – News of 1946

TimeGhost History

Published 5 Mar 20251946 sees the world teetering on the brink of a new global conflict. George Kennan’s long telegram outlines Moscow’s fanatical drive against the capitalist West, while our panel covers escalating espionage, strategic disputes over Turkey, and the emerging ideological battle between the U.S. and the USSR. Tune in as we break down the news shaping the dawn of the Cold War.

(more…)

March 3, 2025

Europe’s Imperial Giants: On the Brink of Collapse? – W2W 09 Q4 1946

TimeGhost History

Published 2 Mar 2025In 1946, Britain, France, and the Netherlands fight to regain control over shattered colonies — from Indonesia’s revolt to Vietnam’s war with France. Meanwhile, the U.S. and USSR maneuver to shape these emerging nations for their own global interests. Will independence spark true liberation, or will it simply swap one master for another?

(more…)

February 17, 2025

The growing problem of “America’s hat”

John Carter’s latest post is excellent — but that’s his usual standard — but it’s of particular interest to inhabitants of what used to be the proud Dominion but who now live in a “post-national state” with “no core identity” as our outgoing prime minister so helpfully explained it:

Canada and the US have been frenemies for most of the last two hundred years. With the exception of some spats in the 19th century, they’ve fought on the same side in all major wars, and haven’t taken up arms against one another. At the same time, Canada has from the very beginning fiercely guarded its independence. Through the 1950s, this came from Canada’s self-conception as an outpost of sober, orderly British traditionalism, in stark contrast to the chaotic liberal revolutionaries across the border. Following the Liberal Party’s cultural revolution in the 1960s, Canada increasingly came to see itself as different from the US primarily in that it was more liberal, in the modern sense, than it’s Bible-thumping, gun-toting redneck cousins – which is to say more socialist, leftist, multicultural, gay-friendly, internationalist, feminist, and so forth. In fairness to Canada, the British government, having long-since fallen under the sway of the Labour party, had followed the same ideological trajectory, so Canada was really just taking its cue from Mother England as it always had. In further fairness to Canada, all of this has been aggressively pushed by Blue America, which has been running American culture (and therefore everyone else’s) until about five minutes ago.

Despite these differences, the US could always rely on Canada being a stable, competently run, prosperous, and happy neighbour – perhaps a bit on the prickly side, given the inferiority complex, but much less of a headache than the entropic narcostate to the south that keeps sending its masses of illiterate campesinos flooding over the banks of the Rio Grande. Canada might be annoying sometimes, but it didn’t cause problems. To the contrary, Canada and the US have maintained one the world’s most productive trading relationships for years: America gets Canadian oil, minerals, lumber, and Canada gets US dollars, technology, and culture.

Now, however, Canada has become a problem for America. Not yet, perhaps, the biggest problem – America has a very large number of extremely pressing problems – but a significant one nonetheless, with the potential to become quite acute in the near future.

The problem is that Canada has become a security threat.

[…]

The next security problem is the border, an issue which Trump has repeatedly stressed as a justification for tariffs. The 49th Parallel is famously the longest undefended border on the planet. It is much longer than the Southern border; there are no barbed wire border fences; most of the terrain is easily traversed – forest, lake, or prairie – in contrast to the punishing desert running across the US-Mexico border. Militarizing the US-Mexico border is already a huge, costly undertaking. Doing the same on the Canadian border would be vastly more challenging.

Canada’s extraordinarily lax immigration policy has, in recent years, led to a much higher encounter rate at border crossings with suspects on the terrorism watch list. These people come into Canada legally, part of the millions of immigrants Ottawa has been importing, every year, for the last few years. When you’re bringing in over one percent of your country’s population every single year, it is simply not possible to properly vet them, and it seems that Ottawa barely even bothers to try. Given that not every such person of interest will get stopped at the border, and that not every terrorist is on a watch list, one wonders how many enemies have already slipped across into the US by way of Canadian airports.

The second border problem is fentanyl. Like the US, Canada has a raging opiod epidemic. We’ve got tent cities, zombies in the streets, needles in the parks, and this is not limited to the big cities – it spills out into the small towns, as well. Like Mexico, Canada has fentanyl laboratories. Precursor chemicals are imported from China by triads, turned into chemical weapons in Canadian labs, and then distributed within Canadian and American markets by predominantly Indian truckers. The occasional busts have turned up vast quantities of the stuff, but have resulted in very few arrests. The proceeds are then laundered through casinos or fake colleges, with the laundered cash then parked in Canadian real estate. There are estimates that the volume of fentanyl money flowing through Canada’s housing markets is significant enough to be a major factor (immigration is certainly the main factor) distorting real estate prices – keeping the housing bubble inflated, propping up Canada’s sagging economy, and pricing young Canadians out of any hope of owning a home or, for that matter, even renting an apartment without a roommate or three.

It’s generally understood, though essentially never acknowledged at official levels, that poisoning North America with opiods is deliberate Chinese policy, both as revenge for the Opium Wars of the 19th century, and as one element in their strategy of unrestricted warfare i.e. the covert but systematic weaponization of every point of contact – economic, industrial, cultural, etc. – between Chinese and Western societies. By allowing the fentanyl trade to continue, the Canadian government is complicit in an act of covert war being waged by a foreign power, one whose casualties include the Canadian government’s own population.

Forgotten War Ep 9 – Kohima – Hell in the Hills

HardThrasher

Published 16 Feb 2025The Battle of Kohima.

Please consider donations of any size to the Burma Star Memorial Fund who aim to ensure remembrance of those who fought with, in and against 14th Army 1941–1945 — https://burmastarmemorial.org/

(more…)

February 6, 2025

Forgotten War Ep 8 – Imphal 44 Pt2 – Edge of Chaos

HardThrasher

Published 4 Feb 2025A video discussing the Battles of Imphal and Kohima at the start of 1944.

Please consider donations of any size to the Burma Star Memorial Fund who aim to ensure remembrance of those who fought with, in and against 14th Army 1941–1945 — https://burmastarmemorial.org/

(more…)

January 26, 2025

Imperial reparations to India are not economically or historically realistic

Apparently the idea of demanding financial reparations from Britain has once again become a talking point among India’s chattering classes. In The Critic, Tirthankar Roy explains why the basis for the demands do not meet economic or historic criteria necessary for the demands to be justified:

The State Entry into Delhi – Leading the 1903 Delhi durbar parade, on the first elephant, “Lakshman Prasad”, the Viceroy and Vicereine of India, Lord and Lady Curzon. Their elephant was lent by the Maharaja of Benares. On the second elephant, “Maula Bakhsh”, the Duke and Duchess of Connaught representing the British royal family. Their elephant lent by the Maharaja of Jaipur. There were 48 elephants of the Main Procession, shown winding its way past the north side of the Jama Masjid.

Painting by Roderick MacKenzie from the Bristol City Museum and Art Gallery via Wikimedia Commons.

Oxfam, in its report “Takers not Makers” claims that imperialist Britain “extracted” $85 trillion from India, “enough to carpet London with £50 notes” four times over. Oxfam took this number from calculations others have done before. The origin of the claim goes back to Dadabhai Naoroji writing 125 years ago, who called the outflow drain. Oxfam uses the number to support a modern movement: a case for reparations that Britain should pay India. With British public finances in a rut, the report’s timing is not ideal. But how good is the case?

[…]

Why did Chaudhuri say drain was “confused” economics? The figure of $85 trillion builds on three bases. First, in the 1760s, as the East India Company started sharing the governance of Bengal with the Nawab’s regime, a part of the taxes of Bengal was used to fund business investment (export of textiles). Second, in the nineteenth century, Indian taxes were used to fund an army that fought imperialist wars to no benefit of India. Third, India maintained an export surplus, which went to fund payments to Britain on mainly four heads: debt service, railway guarantees, pensions to expatriate officers, and repatriated profits on private investment. Naoroji said that these outflows were payment without benefit to India, a drain, and happened because India was a colony. Did he discount the benefits of these transactions?

The Company was a body of merchants who became kingmakers between 1757 and 1765, resulting in a government in Bengal where private and public interests often conflicted. No one knows how serious the conflict was since the Nawab was a partner in the rule. No matter, the case that tax was used for commerce is weak. Within a few years after the transition, the Parliament started taking control of Indian governance, which meant refusing to fund business with taxes. By 1805, the process was complete when Governor Cornwallis declared that “the duties of territorial government [would take] the place of buying and selling”. In between, public finance data are so patchy that it is impossible to find out how much of the Company’s commercial investment was funded by a budgetary grant, borrowings, and profits.

What is the big deal anyway? The Company’s investment of $60 million around 1800 was a tiny 0.06% of India’s GDP. Its textile business generated employment and externalities in India. And the real drain was not the export, but the profits upon exports. We are dealing with an almost invisible transaction, so small it was.

Consider the criticism of the army. British Indian budget, the argument went, paid for the Indian army, which fought wars beyond Indian borders, a subsidy Indian taxpayers paid to the Empire. This claim misreads what the land army really did. The reason it was very big and funded by India was that it was a deterrent to potential conflict amongst the 550 princely states. Interstate conflicts claimed enormous human and economic cost in the late-eighteenth century. The army ended that and effectively subsidised the defences of the princely states. Similarly, the British state subsidised Indian naval capability. Until World War I, the deployment of the army beyond India caused little controversy. The army protected the huge diaspora of Indian merchants and workers. Without the empire’s military might, we would not get Indians doing business in Hong Kong, Aden, Mombasa, or Natal. The War changed the benefit-cost estimates, and in the 1920s, the arrangement ended.

The third point, that export surplus was drain, is the most bizarre. India normally had a commodity export surplus, in effect payment for services purchased by India from Britain. Naoroji thought this was a waste of money. His followers insisted it was. But these claims follow no economic logic. No economics in the world will tell us that an outflow makes a country poor. That assessment depends on what value the payment creates at home. In activist history, there is no discussion of the value, because there is no acknowledgement there could be a value.

January 23, 2025

The Google of the early modern era

Ted Gioia compares the modern market power of the Google behemoth to the only commercial enterprise in human history to control half of the world’s trade — Britain’s “John Company”, or formally, the East India Company which lasted over 250 years growing from an also-ran to Dutch and Portuguese EICs to the biggest ever to sail the seas:

No business ever matched the power of the East India Company. It dominated global trade routes, and used that power to control entire nations. Yet it eventually collapsed — ruined by the consequences of its own extreme ambitions.

Anybody who wants to understand how big businesses destroy themselves through greed and overreaching needs to know this case study. And that’s especially true right now — because huge web platforms are trying to do the exact same thing in the digital economy that the East India Company did in the real world.

Google is the closest thing I’ve ever seen to the East India Company. And it will encounter the exact same problems, and perhaps meet the same fate.

The concept is simple. If you control how people connect to the economy, you have enormous power over them.

You don’t even need to run factories or set up retail stores. You don’t need to manufacture anything, or create any object with intrinsic value.

You just control the links between buyers and sellers — and then you squeeze them as hard as you can.

That’s why the East India Company focused on trade routes. They were the hyperlinks of that era.

So it needed ships the way Google needs servers.

The seeds for this rapacious business were planted when the British captured a huge Portuguese ship in 1592. The boat, called the Madre de Deus, was three times larger than anything the Brits had ever built.

But it was NOT a military vessel. The Portuguese ship was filled with cargo.

The sailors couldn’t believe what they had captured. They found chests of gold and silver coins, diamond-set jewelry, pearls as big as your thumb, all sorts of silks and tapestries, and 15 tons of ebony.

The spices alone weighed a staggering 50 tons — cinnamon, nutmeg, cloves, pepper, and other magical substances rarely seen in British kitchens.

This one cargo ship represented as much wealth as half of the entire English treasury.

And it raised an obvious question. Why should the English worry about military ships — or anything else, really — when you could make so much money trading all this stuff?

Not long after, a group of merchants and explorers started hatching plans to launch a trading company — and finally received a charter from Queen Elizabeth in 1600.

The East India Company was now a reality, but it needed to play catchup. The Dutch and the Portuguese were already established in the merchant shipping business.

By 1603, the East India Company had three ships. A decade later that had grown to eight. But the bigger it got, the more ambitious it became.

The rates of return were enormous — an average of 138% on the first dozen voyages. So the management was obsessed with expanding as rapidly as possible.

They call it scalability nowadays.

But even if they dominated and oppressed like bullies, these corporate bosses still craved a veneer of respectability and legitimacy — just like Google’s CEO at the innauguration yesterday. So the company got a Coat of Arms, playacting as if it were a royal family or noble clan.

As a royally chartered company, I believe the EIC was automatically entitled to create and use a coat of arms. Here’s the original from the reign of Queen Elizabeth I:

January 13, 2025

Forgotten War – Ep 7 – Imphal ’44 Pt1 – Planning Prevents

HardThrasher

Published 12 Jan 2025DO NOT PANIC IF YOU HAVEN’T WATCHED THE OTHER VIDEOS IN THIS SERIES YOU CAN START HERE

A video discussing the planning phase of the Battles of Imphal and Kohima at the start of 1944

Please consider donations of any size to the Burma Star Memorial Fund who aim to ensure remembrance of those who fought with, in and against 14th Army 1941–1945 — https://burmastarmemorial.org/

(more…)

January 2, 2025

Forgotten War – Ep 6 – The Battle of the Admin Box – Feb. 1944

HardThrasher

Published 1 Jan 2025A short video on the highlights of the Battle of the Admin Box, and its build up DO NOT PANIC IF YOU HAVEN’T WATCHED THE OTHER VIDEOS IN THIS SERIES

Please consider donations of any size to the Burma Star Memorial Fund who aim to ensure remembrance of those who fought with, in and against 14th Army 1941–1945 — https://burmastarmemorial.org/

(more…)

January 1, 2025

Mark Steyn – “This is not a healthy development in world affairs”

Mark comments on the ongoing political punch-up over the US government’s H1B visa program for foreign workers:

As you’ll have noticed, the world’s most uniquely unique peaceful transition of power turned suddenly violent over Christmas with various of America’s super-brainy Indians beating up on each other: Nikki Haley, the Boeing board’s token Sikh, lit up Hindu monotheist Vivek Ramaswamy’s tweet like Air Canada overhead baggage in objection to Vivek’s remarks on US “mediocrity”. The offending Ramaswamy tweet was in response to MAGA objections to Trump’s appointment of Madras techie and open-borders fanatic Sriram Krishnan as his AI advisor. This was a very 2025 brouhaha: while you knuckle-draggers down in flyover country were arguing about sub-minimum-wage Hispanics turning down the sheets at Motel Six, the Hindu billionaires have been busy taking over the country.

Is everyone in this all-American punch-up an Indian? Well, no, eventually a South African weighed in. The Boers don’t like the Hindus, do they? I think I got that from Gandhi. Ah, but in this case Elon agrees with Sriram and Vivek.

A couple of very general observations:

1) The MAGA base intuits that H1B visas are a racket. Why wouldn’t they be? Everything else the federal government touches is — from presidential pardons to West Point to Jan 6 justice. America is the third largest nation on earth — a third-of-a-billion people, officially (rather more in actual reality). Why does it need to hire entry-level workers from the first and second largest nations? Yes, yes, too many Americans graduate in non-binary studies rather than any serious academic discipline but simply because you’ve bollocksed up your entire education system is no reason to (as my former National Review colleague John Derbyshire puts it) “import an overclass“.

The MAGA objections to mass immigration (ie, not just illegal immigration) are primarily cultural. They didn’t like it eight years ago when Trump would add to his wall-building promises the line about “and that wall will have a big beautiful door”, and he should have got that by now. Besides, to address the counter-argument more seriously than it merits, a nation of a third-of-a-billion that “needs” to import entry-level accountants is so structurally dysfunctional that no amount of immigration can save it. How about entry-level lawyers? Do we need more of those?

As an aside to that, for all you Constitution fetishists, I’m increasingly sceptical that a Constitution designed for an homogeneous population of two-and-a-half million people can be applied to a third-of-a-billion with a cratering fertility rate of 1.6. The only two more populous nations — China and India — are both more or less conventional ethnostates. Which is a great advantage. America is the only large-scale polity founded on a proposition — that, simply by setting foot on US soil, one becomes American. Immigration on the present transformative scale will nullify the Constitution. So the Dance of the Constitution Fetishists will get even sadder.

The Constitution is increasingly for judges rather than citizens. May be time to import more Supreme Court justices.

2) Besides, H1B is what the government calls, correctly, a “nonimmigrant” visa. One of Rupert Murdoch’s minions offered me an H1B thirty years ago. I looked up the terms and declined to sign on to indentured servitude. You’re not importing “the best and brightest”. You’re assisting well-connected corporations in advantaging themselves at the cost of the citizenry among whom they nominally live. [NR: Emphasis mine.]

3) Have you noticed that almost everyone involved in this spat is a billionaire? Today’s rich are not just rich in the old Scott Fitzgerald they-are-different sense. They approximate more to the condition articulated by Lord Palmerston in his observation that England had no eternal friends or enemies, only eternal interests. For a billionaire, friends and enemies come and go, but, like any medium-sized nation-state, he has his interests.

To most Americans, Elon was largely unknown until he started weighing in on and then buying social media; Vivek was entirely unknown until he ran for president; Sriram is still unknown. But they are far above not just the schlubs who lost their jobs to cheaper H1B types but also to the more famous political class whose poll numbers in Iowa so obsess the hamster-wheel media but which are increasingly irrelevant to anything that matters. Among Sriram Krishnan’s minor claims to “fame” is that he’s the guy who introduced Boris Johnson (remember him?) to Elon Musk — and you can bet that was after desperate wheedling and pleading from the Shagger, not because Elon had any desire for dating tips.

This is not a healthy development in world affairs.

4) Vivek Ramaswamy’s sweeping paean to American “mediocrity” as manifested by everything from prom queens to sitcoms was probably ill-advised but it was certainly entirely sincere — and would be widely shared by his fellow members of the Hindu overclass. The Indian tycoon (and David Cameron advisor) Ratan Tata, who died in October, is best remembered in the UK for his 2011 Vivek-like attack on the natives’ “work ethic“. As Sir Ratan marvelled after buying Jaguar-Land Rover:

I feel if you have come from Bombay to have a meeting and the meeting goes till 6pm, I would expect that you won’t, at 5 o’clock, say, ‘Sorry, I have my train to catch. I have to go home.’

Friday, from 3.30pm, you can’t find anybody in the office.

That may well be true, as Vivek’s musings re Urkel and football jocks may be true. On the other hand, as a rather precocious lad, I observed to my mum that, five years after the Gambia’s independence, nothing seemed to work as well as it did under colonial rule. True, conceded my mother, then added: “But in the end people want to be themselves, as themselves. At least it’s their chaos.”

December 21, 2024

QotD: Portugal’s early expansion in the Indian Ocean

At a cursory glance, the first arrival of Portuguese ships in India must not have appeared to be a particularly fateful development. Vasco da Gama’s 1497 expedition to India, which circumnavigated Africa and arrived on the Malabar Coast near Calicut consisted of a mere four ships and 170 men — hardly the sort of force that could obviously threaten to upset the balance of power among the vast and populous states rimming the Indian ocean. The rapid proliferation of Portuguese power in India must have therefore been all the more shocking for the region’s denizens.

The collision of the Iberian and Indian worlds, which possessed diplomatic and religious norms that were mutually unintelligible, was therefore bound to devolve quickly into frustration and eventually violence. The Portuguese, who harbored hopes that India might be home to Christian populations with whom they could link up, were greatly disappointed to discover only Muslims and Hindu “idolaters”. The broader problem, however, was that the market in the Malabar coast was already heavily saturated with Arab merchants who plied the trade routes from India to Egypt — indeed, these were precisely the middle men whom the Portuguese were hoping to outflank.

The particular flashpoint which led to conflict, therefore, were the mutual efforts of the Portuguese and the Arabs to exclude each other from the market, and the devolution to violence was rapid. A second Portuguese expedition, which arrived in 1500 with 13 ships, got the action started by seizing and looting an Arab cargo ship off Calicut; Arab merchants in the city responded by whipping up a mob which massacred some 70 Portuguese in the onshore trading post in full sight of the fleet. The Portuguese, incensed and out for revenge, retaliated in turn by bombarding Calicut from the sea; their powerful cannon killed hundreds and left much of the town (which was not fortified) in ruins. They then seized the cargo of some 10 Arab vessels along the coast and hauled out for home.

The 1500 expedition unveiled an emerging pattern and basis for Portugal’s emerging India project. The voyage was marked by significant frustration: in addition to the massacre of the shore party in Calicut, there were significant losses to shipwreck and scurvy, and the expedition had failed to achieve its goal of establishing a trading post and stable relations in Calicut. Even so, the returns — mainly spices looted from Arab merchant vessels — were more than sufficient to justify the expense of more ships, more men, and more voyages. On the shore, the Portuguese felt the acute vulnerability of their tiny numbers, having been overwhelmed and massacred by a mob of civilians, but the power of their cannon fire and the superiority of their seamanship gave them a powerful kinetic tool.

Big Serge, “The Rise of Shot and Sail”, Big Serge Thought, 2024-09-13.

December 16, 2024

The academic battle over the legacy of the British Empire

In the Washington Examiner, Yuan Yi Zhu reviews The Truth About Empire: Real histories of British Colonialism edited by Alan Lester:

… the story fitted awkwardly with the new dominant historical narrative in Britain, according to which the British Empire was an unequivocally evil institution whose lingering miasma still corrupts not only its former territories but also modern-day Britain.

When Kipling lamented, “What do they know of England, who only England know?” he was not being elegiac as much as describing a statistical fact. Contrary to modern caricatures, apart from episodic busts of enthusiasm, Britons were never very interested in their empire. At its Victorian peak, the great public controversies were more likely to be liturgical than imperial. In 1948, 51% of the British public could not name a single British colony; three years later, the figure had risen to 59%. Admittedly, this was after Indian independence, but it should not have been that hard. Proponents of the “imperial miasma” theory are right in saying that British people are woefully ignorant about their imperial past; but that was the case even when much of the world was colored red.

The Truth About Empire: Real Histories of British Colonialism is a collection of essays edited by Alan Lester, an academic at the University of Sussex who has been at the forefront of the cultural conflict over British imperialism on the “miasma” side — though, like all combatants, he denies being a participant. Indeed, one of the book’s declared aims is to show that its contributors are not engaged in cultural warring.

Their nemesis, whose name appears 376 times in this book (more often than the word “Britain”) is Nigel Biggar, a retired theologian and priest at the University of Oxford. In 2017, Biggar began a project to study the ethics of empire alongside John Darwin, a distinguished imperial historian. The now-familiar academic denunciations then came along, and Darwin, on the cusp of a quiet retirement, withdrew from the project.

Lester was not part of the initial assault on Biggar but has since then emerged as his most voluble critic. He disclaims any political aims, protesting that he and his colleagues are engaged in a purely scholarly enterprise, based on facts and the study of the evidence.

Yet some of Lester’s public interventions — he recently described a poll showing that British people are less proud of their history than before as an “encouraging sign” — are hard to square with this denial. Biggar, by contrast, is refreshingly honest that his aims are both intellectual and political. I must add that both men are serious scholars, which is perhaps why neither has been able to decisively bloody the other in their jousts.

[…]

“What about slavery?” asks Dubow’s Cambridge colleague Bronwen Everill. Unfortunately, her four pages, which read like a last-minute student essay, do not enlighten us. The most she can manage is to point to an 18th-century African monarch abolishing the slave trade as evidence that the British do not deserve any plaudits for their abolitionist efforts across the world, whose cost has been estimated at 1.8% of its gross domestic product over a period of 60 years.

Meanwhile, Abd al Qadir Kane, Everill’s abolitionist monarch, only objected to the enslavement of Muslims but not to slavery generally, his progressive reputation resting mainly on the misunderstandings of Thomas Clarkson, an overenthusiastic English abolitionist. (Either cleverly or lazily, Everill quotes Clarkson’s misleading account, thus avoiding the need to engage with the historiography on Islamic slavery in Africa.)

Everill’s central argument is that abolitionism allowed Britain to rove the world as a moral policeman and to overthrow rulers who refused to abolish slavery. It is never clear, however, why this was morally bad. If anything, Britain did not go far enough: Well into the 1960s, British representatives still manumitted slaves on an ad hoc basis in its Gulf protectorates, when the moral thing would have been to force their rulers to abolish slavery, at gunpoint if necessary.