TimeGhost History

Published 16 Nov 2025Cyprus, 1950s–60s. An island divided between Greek Cypriots, Turkish Cypriots, and the British Empire becomes the battleground for one of the Cold War’s most explosive regional crises. What begins as a struggle for independence soon spirals into a three-way conflict of nationalism, colonial strategy, and clashing identities — with Archbishop Makarios III, paramilitary groups, Athens, Ankara, and London all pulling in different directions.

In this episode of War 2 War, we uncover how Cyprus became:

- A central front in the decline of the British Empire

- A stage for espionage, guerrilla warfare, and political assassinations

- A diplomatic nightmare for NATO

- A struggle where UN peacekeepers become critical to preventing total collapse

- A conflict whose consequences still shape Europe and the Eastern Mediterranean today

We’ll trace the rise of EOKA, the reaction in the Turkish Cypriot community, the impossible balancing act of Makarios III, and how superpower pressure from the USA and USSR escalated an already volatile situation.

This is the hidden story of how one island’s crisis reshaped the politics of an entire region — and marked the end of Britain as a global imperial power.

(more…)

November 17, 2025

Cyprus on Fire: The 3-Way War That Broke an Empire – W2W 053

July 2, 2025

The Korean War Week 54 – The War is One Year Old – July 1, 1951

The Korean War by Indy Neidell

Published 1 Jul 2025Over a year has passed since North Korean forces crossed the 38th Parallel and invaded South Korea, and while the war has seen the advantage switch hands time and again, one thing it has not seen is any sort of cease fire or peace negotiations. However, that might change soon, as this week both the Chinese and the Americans indicate their willingness to sit down and talk. South Korean President Syngman Rhee, however, is against any cease fire talks that do not set out to meet a big variety of his demands, demands which which the other warring parties do not see as being in their own best interests.

(more…)

April 30, 2025

The Korean War Week 45 – The Chinese Spring Offensive Begins! – April 29, 1951

The Korean War by Indy Neidell

Published 29 Apr 2025This is a week of nothing but battle action as the Chinese Spring Offensive crashes down on the UN forces like a tidal wave — literally hitting them along all of the front lines across the whole Korean Peninsula.

Chapters

00:00 Intro

00:46 Recap

01:59 The First Night

07:25 The Next Day

10:19 The Eastern Sector

13:56 The Kapyong Road

15:57 The Gloster Surrounded

19:48 Flight of the Glosters

(more…)

February 2, 2025

Hierapolis: a city encased in stone

Scenic Routes to the Past

Published 18 Oct 2024Hierapolis — modern Pamukkale, Turkey — was built over hot springs. During the Middle Ages, these encased much of the city in gleaming travertine.

See my upcoming trips to Turkey and other historical destinations: https://trovatrip.com/host/profiles/g…

December 4, 2024

The Korean War Week 024 – Marines Attacked at Chosin Reservoir – December 3, 1950

The Korean War by Indy Neidell

Published 3 Dec 2024On and around the frozen waters of the Chosin Reservoir, the US Marines and the Chinese Communist forces fight out a brutal battle. In the west, the Chinese offensive continues. For the UN forces, there is no chance of victory, but living to fight another day may yet be possible.

Chapters

00:00 Intro

00:48 Recap

01:11 Chosin Reservoir Prelude

03:58 Yudam-ni

06:32 Task Force Faith

08:25 Hagaru

12:58 The Aftermath of Chosin

14:49 The Tokyo Conference

15:56 Wawon and Kunu-ri

20:30 Summary

20:42 Conclusion

(more…)

November 27, 2024

The Korean War 023 – The Eagle Versus the Dragon – November 26, 1950

The Korean War by Indy Neidell

Published 26 Nov 2024Thanksgiving 1950 comes and goes in the snowy north of Korea, and Eighth Army’s push to the Yalu River begins the following day. It soon becomes apparent, though, that the Communist Chinese are ready and waiting for them, in numbers greater than anyone on the UN side have predicted. After weeks of preamble and preparation, the two forces finally collide in full strength.

Chapters

00:00 Intro

00:51 Recap

01:16 X Corps

03:14 Turkey Time

05:50 The US Offensive

09:05 The Second Phase Offensive

12:39 East Flank Disaster

15:27 Summary

15:47 Conclusion

(more…)

November 26, 2024

The ghost airport of Nicosia: Rare glimpse inside the abandoned 1974 battleground

Forces News

Published Jul 20, 2024Nicosia International Airport was once a busy hub full of holidaymakers but since the Cyprus conflict of 1974, it has been frozen in time.

Today, the disused airport resembles a ghost town as it sits abandoned in the 180km buffer zone dividing the Republic of Cyprus and the Turkish-occupied north.

On the 50th anniversary of the conflict, Forces News goes inside the eerie airport and learns how it became the site of a major battle.

(more…)

May 18, 2024

The plight of Greek refugees after the Greco-Turkish War

As part of a larger look at population transfers in the Middle East, Ed West briefly explains the tragic situation after the Turkish defeat of the Greek invasion into the former Ottoman homeland in Anatolia:

“Greek dialects of Asia Minor prior to the 1923 population exchange between Greece and Turkey. Evolution of Greek dialects from the late Byzantine Empire through to the early 20th century leading to Demotic in yellow, Pontic in orange, and Cappadocian in green. Green dots indicate Cappadocian Greek speaking villages in 1910.”

Map created by Ivanchay via Wikimedia Commons.

While I understand why people are upset by the Nakba, and by the conditions of Palestinians since 1948, or particular Israeli acts of violence, I find it harder to understand why people frame it as one of colonial settlement. The counter is not so much that Palestine was 2,000 years ago the historic Jewish homeland – which is, to put it mildly, a weak argument – but that the exodus of Arabs from the Holy Land was matched by a similar number of Jews from neighbouring Arab countries. This completely ignored aspect of the story complicates things in a way in which some westerners, well-trained in particular schools of thought, find almost incomprehensible.

The 20th century was a period of mass exodus, most of it non-voluntary. Across the former Austro-Hungarian, Russian and Ottoman empires the growth in national consciousness and the demands for self-determination resulted in enormous and traumatic population transfers, which in Europe reached its climax at the end of the Second World War.

Although the bulk of this was directed at Germans, the aggressors in the conflict, they were not the only victims – huge numbers of Poles were forcibly moved out of the east of the country to be resettled in what had previously been Germany. The entire Polish community in Lwów, as they called it, was moved to Wrocław, formerly Breslau.

Maps of central and eastern Europe in the 19th century would have shown a confusing array of villages speaking a variety of languages and following different religions, many of whom wouldn’t have been aware of themselves as Poles, Romanians, Serbs or whatever. These communities had uneasily co-existed under imperial rulers until the spread of newspapers and telegraph poles began to form a new national consciousness, usually driven by urban intellectuals LARPing in peasant fantasies.

This lack of national consciousness was especially true of the people who came to be known as Turks; the Balkans in the late 19th century had a huge Muslim population, most of whom were subsequently driven out by nationalists of various kinds. Many not only did not see themselves as Turks but didn’t even speak Turkish; their ancestors had simply been Greeks or Bulgarians who had adopted the religion of the ruling power, as many people do. Crete had been one-third Muslim before they were pushed out by Greek nationalists and came to settle in the Ottoman Empire, which is why there is still today a Greek-speaking Muslim town in Syria.

This population transfer went both ways, and when that long-simmering hatred reached its climax after the First World War, the Greeks came off much worse. Half a million “Turks” moved east, but one million Greek speakers were forced to settle in Greece, causing a huge humanitarian crisis at the time, with many dying of disease or hunger.

That population transfer was skewed simply because Atatürk’s army won the Greco-Turkish War, and Britain was too tired to help its traditional allies and have another crack at Johnny Turk, who – as it turned out at Gallipoli – were pretty good at fighting.

The Greeks who settled in their new country were quite distinctive to those already living there. The Pontic Greeks of eastern Anatolia, who had inhabited the region since the early first millennium BC, had a distinct culture and dialect, as did the Cappadocian Greeks. Anthropologically, one might even have seen them as distinctive ethnic groups altogether, yet they had no choice but to resettle in their new homeland and lose their identity and traditions. The largest number settled in Macedonia, where they formed a slight majority of that region, with many also moving to Athens.

The loss of their ancient homelands was a bitter blow to the Greek psyche, perhaps none more so than the permanent loss of the Queen of Cities itself, Constantinople. This great metropolis, despite four and a half centuries of Ottoman rule, still had a Greek majority until the start of the 20th century but would become ethnically cleansed in the decades following, the last exodus occurring in the 1950s with the Istanbul pogroms. Once a mightily cosmopolitan city, Istanbul today is one of the least diverse major centres in Europe, part of a pattern of growing homogeneity that has been repeated across the Middle East.

But the Greek experience is not unique. Imperial Constantinople was also home to a large Jewish community, many of whom had arrived in the Ottoman Empire following persecution in Spain and other western countries. Many spoke Ladino, or Judeo-Spanish, a Latinate language native to Iberia. Like the Greeks and Armenians, the Jews prospered under the Ottomans and became what Amy Chua called a “market-dominant minority”, the groups who often flourish within empires but who become most vulnerable with the rise of nationalism.

And with the growing Turkish national consciousness and the creation of a Turkish republic from 1923, things got worse for them. Turkish nationalists and their allies murdered vast numbers of Armenians, Greeks and Assyrian Christians in the 1910s, and the atmosphere for Jews became increasingly tense too, with more frequent outbursts of communal violence. After the First World War, many began emigrating to Palestine, now under British control and similarly spiralling towards violence caused by demographic instability.

May 8, 2024

The nonsensical “right of return” debate

George Monastiriakos explains why he should have the right of return to his ancestral homeland:

My family hails from a small Greek village in Anatolia, in modern day Turkey, but I have unfortunately never been to my ancestral homeland because I was born a “refugee” in Montreal. Living in the “liberated zone” of Chomedey, Que., one of the biggest Greek communities in Canada, is the closest I’ve ever felt to my beloved Anatolia.

The Republic of Turkey does not have a legal right to exist. It is an illegitimate and temporary colonial project built by and for Turkish settlers from Central Asia. My ancestors resided on the Aegean coast of Asia Minor for thousands of years before the first Turks arrived on horseback from the barren plains of Mongolia. I will never relinquish my right to return to my ancestral homeland.

If you think these assertions are ridiculous, it’s because they are. I copied them from the shallow, even childish, anti-Israel discourse that’s prevalent on campuses in the United States and Canada, including the University of Ottawa, where I studied and now teach. I am a proud Canadian citizen, with no legal or personal connection to Anatolia. I have no intention, or right, to return to my so-called ancestral homeland. Except, perhaps, for a much-needed vacation. Even then, my stay would be limited to the extent permitted by Turkish law.

The Second Greco-Turkish War concluded with the Treaty of Lausanne in 1923. Among other things, this agreement finalized the forced displacement of nearly one-million Ottoman Greeks to the Kingdom of Greece, and roughly 500,000 Greek Muslims to the newly formed Republic of Turkey. This ended the over 3,000 years of Greek history in Anatolia, and served as a model for the partition of British India, which saw the emergence of a Hindu majority state and a Muslim majority state some two decades later.

With their keys and property deeds in hand, my paternal grandmother’s family fled to the Greek island of Samos, on the opposite side of the Mycale Strait at a nearly swimmable distance from the Turkish coast. While they practised the Greek Orthodox religion and spoke a dialect of the Greek language, they were strangers in a foreign land with no legal or personal connection to the Kingdom of Greece.

The Great War channel produced an overview of the Greco-Turkish War of 1919-1923 that resulted in the vast human tragedy of the expulsion of ethnic Greek civilians from Anatolia and ethnic Turkish civilians from mainland Greece here.

May 4, 2023

Fierce fighting on Gallipoli … before WW1

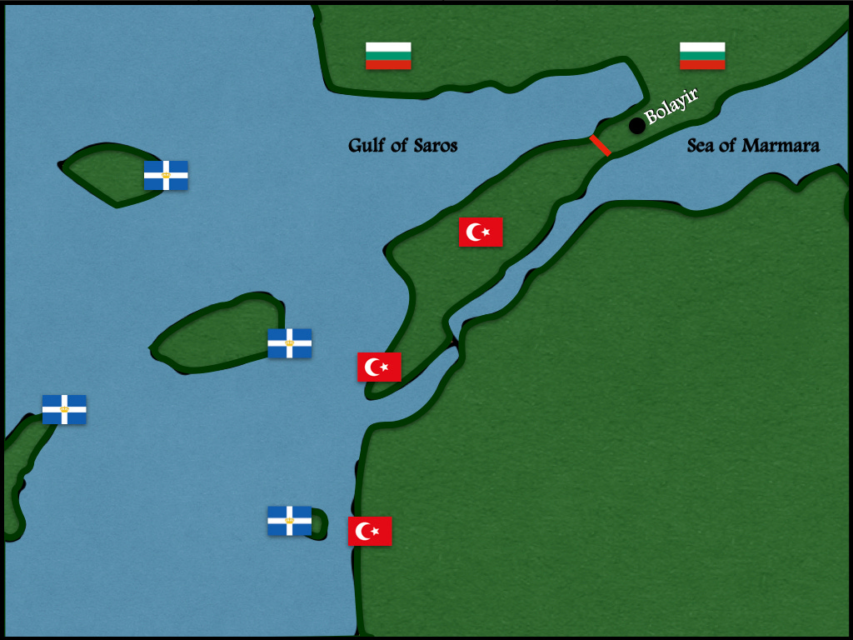

Bruce Gudmundsson outlines the operations of Ottoman Empire forces defending “Turkey in Europe” against Greek and Bulgarian invasion (in alliance with Serbia and Montenegro) in 1913:

In the English speaking world, the name Gallipoli invariably evokes memories of the great events of 1915 and 1916. A location of such strategic importance, however, rarely serves as the site of a single battles. Two years before the landings of the British, Indian, Australian, and New Zealand troops on the south-west portion of the the peninsula (and the concurrent French landings on the nearby mainland of Asia Minor near the ruins of the ancient city of Troy), Ottoman soldiers defended the Dardanelles against the forces of the Balkan League.

By the end of January of 1913, the combined efforts of Greece, Serbia, Montenegro, and Bulgaria had driven Ottoman forces from most of “Turkey in Europe”. Indeed, the only intact Ottoman formations on European soil were those trapped in the fortress of Adrianople, those holding the fortified line just west of Constantinople, and those that had recently arrived at Gallipoli.

Soon after arriving, the Ottoman forces on Gallipoli began to build a belt of field fortifications across the narrowest part of the peninsula, a line some five kilometers (three miles) west of the the town of Bolayir. At the same time, they occupied outposts some twenty kilometers east of the line, at the place where the peninsula connected to the mainland.

On 4 February 1913, the Bulgarians attacked. On the first day of this attack, they drove in the Ottoman outposts. On the second day, they broke through a hastily erected line of resistance, thereby convincing the Ottoman forces in front of them to evacuate Bolayir. However, rather than taking the town, or otherwise attempting to exploit their victory, they withdrew to positions some ten kilometers (six miles) east of the Ottoman earthworks.

While the Ottoman land forces returned to the earthworks along the neck of the Peninsula, ships of the Ottoman Navy operating in the Sea of Marmora located, and began to bombard, the Bulgarian forces near the coast. This caused the Bulgarians to move inland, where they took up, and improved, new positions on the rear slopes of nearby hills.

On 9 February, the Ottomans launched a double attack. While the main body of the Ottoman garrison of Gallipoli advanced overland, a smaller force, supported by the fire of Ottoman warships, landed on the far side of the Bulgarian position. Notwithstanding the advantages, both numerical and geometric, enjoyed by the Ottoman attackers, this pincer action failed to destroy the Bulgarian force. Indeed, in the course of two failed attacks, the Ottomans suffered some ten thousand casualties.

Though the Ottoman maneuver failed to dislodge the Bulgarians from their trenches, the two-sided attack convinced the Bulgarian commander to seek ground that was, at once, both easier to defend against terrestrial attack and less vulnerable to naval gunfire. He found this on the east bank of a river, thirteen kilometers (eight miles) northeast of Bolayir and ten kilometers (six miles) north of the place where the Ottoman landing had taken place.

April 24, 2023

Canada won’t meet its defence spending targets, and Trudeau is totally fine saying this to our allies, if not to the public

Canadian defence freeloading has been a hallmark of Canadian government policy since 1968, and as The Line confirms in their weekend dispatch, it should be no surprise that Justin Trudeau is okay continuing his father’s basic policies:

A story we’ve been watching in recent weeks was the remarkable leak of sensitive U.S. national security documents onto the dark web, and from there, widely across social media. A young member of the Air National Guard has been arrested and now faces serious charges. News reports suggest that he had access to classified material at work and began sharing it privately with a small group of online friends, apparently simply to impress and inform them, with no broader political agenda. Some of those friends, in turn, appear to have leaked the documents further afield. It took months before anyone noticed, but once picked up by several individuals with large followings — including some who are none-too-friendly to the U.S. and Western alliance — the story exploded and the full scope of the leak was finally discovered.

This is, for the U.S., a huge embarrassment and a diplomatic nightmare. For us, it was simply a fascinating story. This week, though, we suddenly had the coveted Canadian Angle: the Washington Post claims to have reviewed one of the leaked documents, apparently prepared for the American Joint Chiefs of Staff, that assesses Canada’s military serious military deficiencies, and also reports that Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has privately told fellow NATO leaders that Canada isn’t going to hit NATO’s two-per-cent-of-GDP spending target.

To wit:

“Widespread defense shortfalls hinder Canadian capabilities,” the document says, “while straining partner relationships and alliance contributions.”

The assessment, which bears the seal of the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff, says Germany is concerned about whether the Canadian Armed Forces can continue to aid Ukraine while meeting its NATO pledges. Turkey is “disappointed” by the Canadian military’s “refusal” to support the transport of humanitarian aid after February’s deadly earthquake there, the document says, and Haiti is “frustrated” by Ottawa’s reluctance to lead a multinational security mission to that crisis-racked nation.

Your Line editors just sort of sighed heavily and rubbed their temples when they read that. It was, to us, nothing we didn’t know already. It was actually almost some kind of a relief to know that the PM will at least say privately what he won’t admit publicly: we aren’t living up to our pledge, and don’t plan to.

The Post says that Trudeau told NATO that there won’t be much more military spending in this country until the political situation here changes. We aren’t sure if he meant the priorities of the voters or the composition of our parliament. It doesn’t matter — it’s true either way. We are disappointed, but again, in no way surprised, to see Trudeau seeing this as an issue that he’ll just accept as-is, as opposed to attempting the hard work of showing actual leadership. He’s always been more about the easy path of demonstrative gestures instead of working hard to achieve real change.

But hey. In this, he has a lot of company. The Tories under Harper were marginally better on defence, but not nearly good enough. We have little faith — next to none, really — that PM Poilievre would do any better on defence. What bums us out the most about this issue is that we recognize and even agree that the choice to neglect defence and shovel those dollars instead into other, more popular vote-buying files does indeed make political sense. It’s what the voters want. We wish it were otherwise. We’ve spent big chunks of our careers trying to change their minds. Our record to date is one of total, utter failure.

Still, never say die, right? So we’ll make this point: we understand and accept the criticism sometimes made by Canadian commentators, who argue that the two-per-cent-of-GDP target is arbitrary and somewhat meaningless. We don’t entirely agree — targets are useful, and two per cent seems reasonable. But we’d be open to an argument that Canada could still punch above its weight in the alliance, even while spending less, if we could deliver key capabilities.

But … we can’t. We probably could, once upon a time, but we can’t even do that now. The air force is a mess. The navy is a mess. The army is a disaster, and couldn’t even send Nova Scotia all the help it asked for after Hurricane Fiona. Sending a token plane or ship on a quick foreign jaunt is symbolism, not above-weight-punching. And the symbolism taps us out.

So we have to pick what we’re doing here, fellow Canucks. We can meet the two-per-cent target. We can find other ways to meaningfully contribute. Or we can do neither of those things, and admit it, but only in private. Right now, alas, we’ve chosen that third option. We see no sign that’ll be changing any time soon.

Pierre Trudeau discovered that Canadian voters are all too willing to accept “peace dividends” in the form of shorting defence spending to goose non-military spending, and few prime ministers since then have done much more than gesture vaguely at changing it. Worse, it’s also quite accepted practice for defence procurement to prioritize “regional economic benefits” over any actual military requirement, which often means Canada buys fewer items (ships, planes, helicopters, tanks, trucks, etc.) at significantly higher prices as long as there’s a shiny new plant in Quebec or New Brunswick that can be the backdrop for government ministers and party MPs to use as a backdrop during the next election campaign. Military capability barely scrapes into the bottom of the priority list on the few occasions that the government feels obligated to spend new money on the Canadian Armed Forces.

Worse, every penny of “new” spending on the military gets announced many times over before any actual cheques are issued, which helps to disguise the fact that it’s the same thing all over again — sometimes for periods stretching out into years. The Canadian military has a well-deserved reputation for keeping ancient equipment up and running for years (or decades) after all our peer nations have moved on to newer kit. It’s a tribute to the technical and maintenance skills of the units involved, but it probably absorbs far more resources to do it over replacing the stuff when it begins to wear out, and it reduces the number available to, and the combat effectiveness of, the front-line troops when they are needed.

April 23, 2023

The Biggest Offensive in Japanese History – WW2 – Week 243 – April 22, 1944

World War Two

Published 22 Apr 2023Japan Launches Operation Ichigo in China, their largest offensive of the war … or ever, but over in India things are not going well for the Japanese at Imphal and Kohima. The Allies also launch attacks on the Japanese at Hollandia, while over in the Crimea, the German defenses at Sevastopol are cracking under Soviet pressure.

(more…)

April 19, 2023

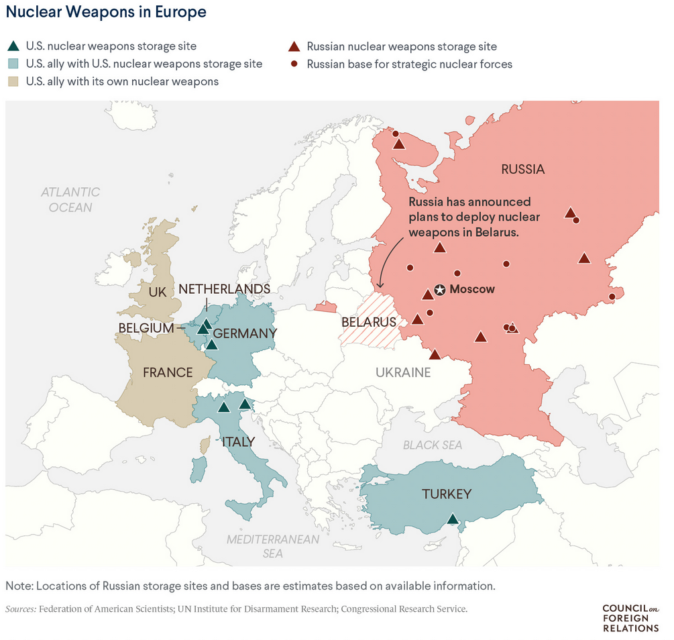

Time to remove US nuclear weapons from Europe?

CDR Salamander has long advocated getting the final few American “tactical” nuclear weapons off European soil and makes the case for doing it now:

It may seem like a strange thing to propose while there is the largest land war in Europe since 1945 going on, but as it is something I’ve been a supporter of for a few decades I might as well be consistent: we are long overdue to remove American nuclear weapons from Europe.

It is 2023. Just look at this map.

[…]

The Soviet Union stopped existing over three decades ago.

Even though we’ve decreased from 7,000 warheads down to 100 … there really is no reason to keep what remains in Europe.

- Gravity bombs on continental Europe – that require tactical aircraft to deliver them – are the least survivable, reliable, or timely way to deliver a nuclear weapon.

- There is no such thing as a tactical nuclear weapon. I don’t care what some theorist proposes to defend their pet theories, you lob one nuke an order of magnitude larger than the Hiroshima bomb and only a foolish nation would let their strategic nuclear forces stay unused and in danger.

- Gravity bombs are not a first strike weapon and are a poor second strike weapon. As such, you have to consider that the the time gap from approval to flash-boom would be so long the war would be over before your F-XX pickled their nuke over their target – even if the aircraft made it off the ground.

- If they are NATO weapons, you not only have to get NATO to approve their use, but host nation to as well … in addition to the USA. Do you really think the Russians would not leverage their influence with the useful idiots in the Euro-Green parties, former communists, and general black-block anti-nuke activists to politically of physically stop the use of the nukes, especially in BEL, NLD, DEU, and ITA? Add that to point 3 above.

- Especially with the weapons in Turkey – the risk of these bombs having a bad day due to human or natural causes is non-zero. In the days of mutually assured destruction, those non-zero odds were manageable, but there is no reasonable person in the third decade of the 21st Century who can with a straight face explain to you why any tactical, operational, or strategic use justify their presence. They deter no enemy, but puts every friend in danger.

- Look again at the map above. Exactly what target set are you going to “service” at that range (non-refueled)?

- If things go nuclear in Europe then the right weapons are either British, French, and if they must be American are sitting in a silo in CONUS, a SSBN in the Atlantic, or a B-2 in Missouri.

April 15, 2023

Do the Germans Know About Operation Overlord?

World War Two

Published 14 Apr 2023We are getting closer and closer to D-Day and the potential liberation of Nazi Europe. But how much do the Germans know about this? Is the leak inside the British Embassy in Ankara enough to thwart the efforts of Operation Bodyguard, Operation Fortitude, and everything else the Allies are doing to deceive Adolf Hitler? Let’s find out. This is the story of Cicero.

(more…)

March 14, 2023

Turkey has always been the awkward ally in NATO, but for how much longer?

In Strategika, Zafiris Rossidis examines the shift of Turkish sentiment away from its longstanding role in the NATO alliance and toward a more Russian-friendly and more independent stance in international affairs:

A poll conducted in December 2022 by the Turkish company Gezici found that 72.8% of Turkish citizens polled were in favor of good relations with Russia. By comparison, nearly 90% perceive the United States as a hostile country. It also revealed that 24.2% of citizens believe that Russia is hostile, while 62.6% believe that Russia is a friendly country. Similarly, more than 60% of respondents said that Russia contributes positively to the Turkish economy.

Turkey began to distance itself from the United States as early as 2003, when it refused the passage of American troops to Iraq. In 2010, it destroyed the U.S.–Israel–Turkey triangle, breaking up with Israel. In 2011, Turkey implemented a policy in Syria that was hardly in line with U.S. interests. The final distancing took place in 2016, with the July coup, for which Turkey blamed the United States.

Turkey considers itself very important to the United States but declares that Ankara can live without Washington. This concept has become the point of departure for Turkey in its quest to reconstitute the Ottoman Empire. Minister of the Interior Süleyman Soylu declares that the Turkish government will design the new world order with the help of Allah, and Western powers will eat the dust behind almighty Turkey (December 8, 2022).

According to a RAND Corporation volume on Turkey, there are four scenarios for the future of Turkish strategic orientation: 1) Turkey will remain a difficult partner for the United States; 2) Turkey will become democratic and unite with the West; 3) Turkey will be between East and West, but have better relations with powers such as China, Iran, and Russia, than with the U.S. and the EU; and 4) Turkey will completely abandon the West.

From the evidence in the case of the Russian–Ukrainian war, Russia, China, Turkey, and Iran justify the Russian invasion since NATO and the EU have designs on their neighborhood. Above all, they are united by a common hatred for the West. They are frenemies and they know it: on the contrary, the U.S. tends to invest in frenemies as if they were true friends.

The U.S. observed the rapprochement of Turkey and Russia without renouncing the traditional alliance with Turkey, which today has no longer such importance. Turkey was useful when it was an “enemy” of the USSR and the U.S. made far too many concessions for the sake of this useful enmity. In short, there is some inertia in the modification of the principle “the enemy of my enemy is my friend”, as of course “the friend of a friend is my friend”. Turkey’s role in NATO worries the U.S., as Ankara–Moscow relations have acquired some shared strategic characteristics.

?he attraction between the two countries lies in their equally authoritarian governance models and the fact that their strategic culture and operational codes bear similarities: Both countries are revisionist, aggressive, and assertive in their regions; both countries claim to be encircled, which they use as a pretext for their unilateral actions; and both countries have militarized their foreign policy, waging hybrid warfare, resorting to proxy warfare, and blackmailing countries that offer resistance. Russia and Turkey cooperate on natural gas and oil pipelines; Russia has sold weapons such as the S-400 missile system to Turkey; Russia has provided technical assistance in the construction of Turkey’s nuclear plants; the two nations have collaborated in Central Asia (i.e., Azerbaijan); they import and export each other’s commodities; and Turkey has illegally transported Russian fuel to China and Iran, thereby bypassing sanctions on Russia, to mention only a few.

But the big issue for U.S.–Turkey relations against the backdrop of the Russian–Ukrainian war has four strands: First, the issue of the important role Turkey plays in the grain export agreement, which if cancelled will create a food crisis in Africa. Second, Turkey’s blackmailing of the NATO candidacies of Sweden and Finland. Third, the Turkish application to purchase the F-16 and the possible conflict between Congress and the Biden administration over the administration’s request to grant Turkey the license to do so. Finally, Turkey’s non-adoption of NATO sanctions against Russia. The possibility of Erdoğan using a strategy of tensions with Greece (e.g., multiple violations of Greek airspace, aggressiveness in the Aegean, weaponization of immigration, threats of bombing Athens with the new “Tayfun” short-range ballistic missile) to rally the electorate around his party and detach it from any opposition — all recent polls have AKP trailing the opposition — prior to the June election is one explanation for Turkey’s behavior that is being considered by the U.S., which nonetheless is angered that Turkey is the only NATO country that has not adopted the sanctions against Russia.