Trying to predict specific events is of course a mug’s game, but the trend lines are easy to spot. The danger is the nearly irresistible temptation to retcon psychological events into political decisions.

Knowing full well how dumb it is to bring up World War II on the Internet, consider that a pretty reasonable case can be constructed for Operation Barbarossa. Having purged all their competent, experienced officers, the Red Army had just gotten their clocks cleaned by the Finns in the Winter War. Yeah, the Soviets “won” in the end, but with that disparity of forces, there’s pretty much no possible “win” that doesn’t look like a loss … and the Soviets, to put it mildly, were nowhere near that best-case scenario. Moreover, even if you took the show trials for exactly that — kangaroo courts — their very existence showed there was a deep rift at the very top of the Soviet leadership. Anyone, not just Hitler, could be forgiven for thinking that the Soviet Union would collapse under one big sledgehammer blow.1

It works the other way, too. If we accept the “Suvorov Thesis”, that Hitler only attacked Stalin because Stalin was gearing up to attack Hitler, then we can easily construct a similar case from The Boss’s perspective: The Wehrmacht can’t play defense. The one time they came up against anything approaching a real opponent with technological parity (the Battle of Britain), it was at best a bloody draw, more than likely a stinging defeat. And the Hitler regime was reeling, internally. No show trials for der Führer, but Rudolf Hess, who was at least the number three man in the Reich and at the time Hitler’s heir apparent, had just defected to the British. Anyone, not just Stalin, could be forgiven for thinking that the Third Reich would collapse under one big sledgehammer blow.

See what I mean? Both of those cases are quite plausible, and fit with most known historical facts … and yet, they’re retcons. “Rationalizations” might even be a better word, because the thing is, even though those arguments are “logical”, and might indeed have been convincing to important people at the time, that’s not why Hitler did what he did, or why Stalin would’ve done what he would’ve done under the Suvorov Thesis. No, the truth is simpler, and much more horrifying: They would’ve done it anyway, because that’s who they were.

That’s what the Castle Wolfenstein people got right about the Nazis. Same deal with that Amazon show (which was interesting for a season) The Man in the High Castle. In the real world, there’s no possible way the Nazis could’ve invaded the USA, no matter how it turned out on the Eastern Front …

… but in the real world they would’ve tried nonetheless, somehow, because that’s just who they were. Everything Stalin, Khrushchev, et al did during the Cold War here in the real world, Hitler, Heydrich, and the gang would’ve done in the Castle Wolfenstein world where the Battles of Stalingrad and Kursk went the other way.2 They couldn’t have done any different, without being different people, and while it’s fun to speculate on questions like “who would’ve been the Nazi Gorbachev, who self-destructed the Reich by attempting however you say ‘perestroika‘ in German”, it’s not really germane.

Severian, “The Man in the High Chair”, Rotten Chestnuts, 2021-07-05.

1. And Soviet losses were stupendous, utterly mind-boggling, in the first few months of Barbarossa. Tanks and planes destroyed in their tens of thousands, prisoners captured in millions. Even as it became clear that OKW had underestimated Red Army strength by orders of magnitude, it was still almost inconceivable that they had anything left to fight with. Just one more push …

2. This is actually the world of a fun novel, Robert Harris’s Fatherland.

October 2, 2024

September 16, 2024

Who Really Won The Korean War?

Real Time History

Published May 17, 2024Only five years after the end of WW2, the major nations of the world are once again up in arms. A global UN coalition and an emerging Chinese juggernaut are fighting it out in a war that will see both sides approach the brink of victory — and defeat.

(more…)

August 25, 2024

Soviet Victory in Manchuria – WW2 – Week 313 – August 24, 1945

World War Two

Published 24 Aug 2024The Soviet Red Army completes its conquest of Manchuria and the northern half of Korea this week, although Japanese Emperor Hirohito announced Japan’s surrender already last week. Behind the scenes are machinations going on by Josef Stalin and Mao Zedong that they hope will lead to a Communist China in future. Vietnam might well be going communist right now, though, for the August revolution continues with the Viet Minh taking ever more control.

00:00 Intro

00:34 Recap

00:49 Chiang, Mao, and Stalin

07:32 Soviet victory in Manchuria

09:08 Viet Minh taking control

11:45 Summary

12:31 Conclusion

13:20 Julius Poole memorial

(more…)

July 28, 2024

Allies Issue Potsdam Declaration – WW2 – Week 309 – July 27, 1945

World War Two

Published 27 Jul 2024China, Britain, and the US issue a Declaration demanding Japan’s unconditional surrender, and promising complete destruction if this does not happen and happen soon. The plan is to for the Americans to use their atomic bombs on Japan if she does not comply, but by the end of the week the Japanese have not replied. They still have hopes for the Soviets to mediate some sort sort of peace. What they don’t have is a navy, as its final destruction comes this week.

00:00 Intro

00:50 Recap

01:32 The Potsdam Conference

04:41 Japanese Hopes

05:56 The Potsdam Declaration

10:53 The Initial Reaction

14:48 The End Of The Japanese Navy

15:05 The War On Land

19:10 Summary

19:30 Conclusion

(more…)

April 25, 2024

Were the Waffen-SS Really Germany’s Elite Fighters? – WW2 – OOTF 35

World War Two

Published 24 Apr 2024It’s time for another thrilling installment of Out of the Foxholes, but what sort of questions does Indy answer today? Well, it’s good stuff — about Allied security and logistics at the major conferences, about what the British navy was doing once the Atlantic and Mediterranean were secure, and about the skills (or lack thereof) of the soldiers of the Waffen SS. How can you live without knowing about such things? I suppose it’s possible, but it would be a sad life indeed, so check it out!

(more…)

April 17, 2024

Soviet Berlin Offensive Begins – WW2 – Week 294B – April 16, 1945

World War Two

Published 16 Apr 2024The final Soviet assault on Berlin begins today. The Soviets have two million men supported by tens of thousands of guns, tanks, and aircraft. Opposite them stand millions of men and boys of the German Wehrmacht, Waffen SS, Volkssturm, and Hitler Youth. The forces of Nazism are weakened and disorganised but determined to fight on as long as possible.

00:41 Roosevelt’s death

03:09 Preparations for the Soviet drive on Berlin

08:49 Zhukov’s Offensive

12:48 Konev’s Offensive

14:57 Summary & Conclusion

(more…)

April 14, 2024

Soviets Take Vienna and Königsberg – WW2 – Week 294 – April 13, 1945

World War Two

Published 13 Apr 2024The prizes of Vienna and Königsberg fall to the Soviets as they continue what seems an inexorable advance. In the West the Allies advance to the Elbe River, but there they are stopped by command. The big news in their national papers this week is the death of American President Franklin Roosevelt, which provokes rejoicing in Hitler’s bunker. The Allied fighting dash for Rangoon continues in Burma, as does the American advance on Okinawa, although Japanese resistance is stiffening and they are beginning counterattacks.

Chapters

00:32 Recap

01:05 Operation Grapeshot

01:57 Roosevelt Dies

06:01 Soviet Attack Plans for Berlin

12:45 Stalin’s Suspicions

14:31 The fall of Königsberg

17:02 The fall of Vienna

18:38 Japanese Resistance on Okinawa

20:34 The War in China

21:09 Burma and the Philippines

22:38 Summary

22:57 Conclusion

25:05 Memorial

(more…)

March 17, 2024

QotD: Imperial Japan and Nazi Germany never had a “long game” … but Stalin did

Though both the Germans and the Japanese had every intention of starting major wars, as everyone knows they seemingly put zero thought into what they’d do once they won. I know, I know, [Himmler] had his sweaty wet dreams about Wehrbauern on the vast Russian steppes, but all but the most rudimentary post-victory planning seems to have been beyond the Third Reich’s capacity — the Reich Resettlement Office, for instance, was tiny even when the war looked like it would be over by Christmas. The Japanese were, if anything, even dumber — they honestly seemed to believe they could run China, all of it, and even India Manchukuo-style.

The Russians, meanwhile, never stopped playing the long game. While Goebbels made a few token gestures at rapprochement with “the West” (yeah, they called it that), and to sell Nazism to ditto, his heart wasn’t in it, any more than the Japanese’s heart was in their “Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere” hooey. Stalin, by contrast, was always pimping Communism to the West — even in the deepest, darkest days of the war, when it looked like the Wehrmacht was about to march into Moscow, the propaganda directed at the West continued full blast.

Like the German and Japanese aircraft industries, the German propaganda industry was ideologically locked into its core mission: To sell Nazism to Germans. And they were aces at it, no doubt … but then the mission changed. The smart thing for the Germans (and Japanese) to have done with their conquered territories was, in the context of the war, to ease up on the Nazi shit for the duration. The Nazis could’ve had zillions of Ukrainians fighting for them in 1941 just as the Japanese probably could’ve waltzed into India in 1941 had they not been so … well, so Japanese, in the rest of the Pacific rim. Stalin would’ve done it in a heartbeat, had the situation been reversed, and to hell with “authentic” Marxism-Leninism. Win the war first; square the ideology later.

As this is running way long, one example should suffice. Goebbels approached the task of selling Nazism to Germans in the most German way possible: He created the Reich Culture Chamber, which controlled all newspapers, radio broadcasts, film distribution, etc. And it worked, as far as it went — Goebbels deserves his “evil genius” rep — but as we’ve seen, that locked the leadership into an ideological straightjacket. Telling the Wehrmacht to ignore the Commissar Order and buddy up with the Ukrainians would’ve been the smart thing to do, militarily, but it was culturally impossible. Goebbels did his job too well … and then the mission changed.

The Soviets had a similar problem inside the USSR, but — here’s Stalin’s evil genius — they had free reign in propagandizing the West. Goebbels hardly bothered, but the Soviets poured massive resources into it. Forget, as far as you can, everything you think you know about “Nazism” […]. Even if you look at it as objectively as possible, it still seems ridiculous, and there’s a simple explanation for that — it’s not for you. Unless you were a pure blooded Aryan, actually living in Germany (or within Germany’s potential military reach), [they] couldn’t care less about you. Which made being a “Nazi” in, say, America uniquely pointless — you just look like a bigot at best, a traitorous bigot at worst.

Being a “Communist”, though? That was universal. Indeed, that made you a Smart person, a very very smart person, and morally superior to boot. Why? Because you care so much that you’ve mastered this large body of deliberately esoteric doctrine, comrade … all straight out of the NKVD playbook. And if actual life as it was lived in the Soviet Union didn’t quite measure up to the promises, well, that’s because they didn’t have the right people — people like YOU — running things. It’s fucking brilliant — a totally ideologically closed, indeed brutal, system at home, presented as the most open-minded, enlightened, tolerant one possible abroad.

Which is why Joey G. needed a huge Reich Culture Chamber that never came close to justifying its budget, and Stalin needed, effectively, nothing. Being so very, very Smart, wannabe “elites” in the West were happy to spread Commie propaganda for free. The NKVD, let alone the Gestapo, ain’t got shit on the Junior Volunteer Thought Police of Twitter and Facebook …

… which forces us to confront the question: Which model of propaganda are our rulers using? Has the one morphed into the other? Is it real, or is it just “German efficiency”?

Severian, “The Myth of German Efficiency”, Rotten Chestnuts, 2021-05-26.

February 12, 2024

Yalta, When Stalin Split the World – a WW2 Special

World War Two

Published 11 February 2024Indy and Sparty take you through the negotiations at Yalta as The Big Three thrash out the shape of the postwar world. As the splits between East and West continue to deepen, who will come out on top?

(more…)

February 10, 2024

The War Goals to End WW2 in 1945 – a WW2 Special

World War Two

Published Feb 8, 2024While World War Two looks like it is about to end, the belligerent powers have vastly different goals for that end. Differences that may or may not prolong the war, will decide the survival of tens of millions of people, and the future fate of all of Humanity.

(more…)

January 12, 2024

Eastern Front Deployments, January 11, 1945 – a WW2 Special

World War Two

Published 11 Jan 2024The Soviets are just about to kick off a series of enormous offensives all along the Eastern Front. Here’s a look at the forces who are to attack, and those who will be defending.

(more…)

December 12, 2023

August 25, 2023

The German Democratic Republic, aka East Germany

Ed West visited East Berlin as a child and came away unimpressed with the grey, impoverished half of Berlin compared to “the gigantic toy shop that was West Berlin”. The East German state was controlled by the few survivors of the pre-WW2 Communist leaders who fled to the Soviet Union:

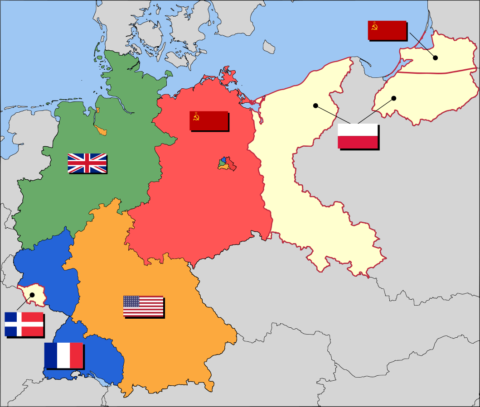

Occupation zone borders in Germany, 1947. The territories east of the Oder-Neisse line, under Polish and Soviet administration/annexation, are shown in cream as is the likewise detached Saar protectorate. Berlin is the multinational area within the Soviet zone.

Image based on map data of the IEG-Maps project (Andreas Kunz, B. Johnen and Joachim Robert Moeschl: University of Mainz) – www.ieg-maps.uni-mainz.de, via Wikimedia Commons.

In my childish mind there was perhaps a sense that East Germany, the evil side, was in some way the spiritual successor both to Prussia and the Third Reich – authoritarian, militaristic and hostile. Even the film Top Secret, one of the many Zucker, Abrahams and Zucker comedies we used to enjoy as children, deliberately confused the two, the American rock star stuck in communist East Germany then getting caught up with the French resistance. The film showed a land of Olympic female shot put winners with six o’clock shadows, crappy little cars you had to wait a decade for, and a terrifying wall to keep the prisoners in – and compared to the gigantic toy shop that was West Berlin, I was not sold.

I suppose that’s how the country is largely remembered in the British imagination, a land of border fences and spying, The Lives of Others and Goodbye Lenin. When the British aren’t comparing everything to Nazi Germany, they occasionally stray out into other historic analogies by comparing things to East Germany, not surprising in a surveillance state such as ours (these rather dubious comparisons obviously intensified under lockdown).

This is no doubt grating to East Germans themselves, but perhaps more grating is the sense of disdain often felt in the western half of Germany; for East Germans, their country simply ceased to exist in 1990 as it was gobbled up by its larger, richer, more glamorous neighbour, and has been regarded as a failure ever since. For that reason, [Katja] Hoyer’s book [Beyond the Wall] is both enjoyable holiday reading and an important historical record for an ageing cohort of people who lived under the old system. To have one’s story told, in a sense, is to avoid annihilation.

Despite the similarities between the two totalitarian systems, East Germany almost defined itself as the anti-fascist state, and its origins lie in a group of communist exiles who fled from Hitler to seek safety in the Soviet Union. Inevitably, their story was almost comically bleak; 17 senior German Marxists in Russia ended up being executed by Stalin, suspected by the paranoid dictator of secretly working for Germany. Even some Jewish communists were accused of spying for the Nazis — which seems to a rational observer unlikely. As Hoyer writes, “More members of the KPD’s executive committee died at Stalin’s hands than at Hitler’s”.

Only two of the nine-strong German politburo survived life in Russia, one of these being Walter Ulbricht, the goatee-bearded veteran of the failed 1919 German revolution and communist party chairman in Berlin in the years before the Nazis came to power.

The war had brutalised the eastern part of Germany far more than the West. It suffered the revenge of the Red Army, including the then largest mass rape in history, and the forced expulsion of millions of Germans from further east (including Hoyer’s grandfather, who had walked from East Prussia). The country was utterly shattered.

From the start the Soviet section had huge disadvantages, not just in terms of raw materials or industry – western Germany has historically always been richer — but in having a patron in Russia. While the Americans boosted their allies through the Marshall Plan, the Soviets continued to plunder Germany; when they learned of uranium in Thuringia they simply turned up and took it, using locals as forced labour.

“In total, 60 per cent of ongoing East German production was taken out of the young state’s efforts to get on its feet between 1945 and 1953,” Hoyer writes: “Yet its people battled on. As early as 1950, the production levels of 1938 had been reached again despite the fact that the GDR had paid three times as much in reparations as its Western counterpart.”

After the war, so-called “Antifa Committees” formed across the Soviet zone, “made up of a wild mix of individuals, among them socialists, communists, liberals, Christians and other opponents of Nazism”. Inevitably, a broad and eclectic left front was taken over by communists who soon crushed all opposition.

And as with many regimes, state oppression grew worse over time. “By May 1953, 66,000 people languished in East German prisons, twice as many as the year before, and a huge figure compared to West Germany’s 40,000. The General Secretary’s revival of the ‘class struggle’, officially announced in the summer of 1952 as part of the state’s ‘building socialism’ programme, had escalated into a struggle against the population, including the working classes.” The party was also becoming dominated by an educated elite, as happened in pretty much all revolutionary regimes.

Protests began at the Stalinallee in Berlin on 16 June 1953, where builders marched towards the House of Ministries and “stood there in their work boots, the dirt and sweat of their labour still on their faces; many held their tools in their hands or slung over their shoulders. There could not have been a more fitting snapshot of what had become of Ulbricht’s dictatorship of the proletariat. The angry crowd chanted, ‘Das hat alles keinen Zweck, der Spitzbart muss weg!’ – ‘No point in reform until Goatee is gone!'”

The 1953 protests were crushed, the workers smeared as fascists, but three years later came Khrushchev’s famous denunciation of Stalin, which caused huge trauma to communists everywhere. “The shaken German delegation went back to their rooms to ponder the implications of what they had just learned.” By breakfast time, “Ulbricht had pulled himself together”, and decreed the new party line. Stalin, it was announced “cannot be counted as a classic of Marxism”.

June 23, 2023

June 7, 2023

QotD: A “second front” in 1943

Which brings us to the debate about the possibility of an invasion in 1943 – Roundup. Something that a surprising number of historians, and even a few not entirely incompetent generals, have suggested might have been possible, and should have been tried.

There are some points in their favour. The invasions of North Africa definitely took resources that could have been built up in Britain, and therefore slowed things down. (And the withdrawal of the new escort carriers, escort groups, and shipping from the Battle of the Atlantic for the North African adventure, definitely did huge damage in the loss of shipping and supplies, slowing things down further.) As a result the huge buildup in North Africa was much easier to use against Italy before moving on to France. Certainly another distraction or delay … but only if you don’t think that knocking Italy out of the war would make Germany weaker!

But once Sledgehammer [the plan to invade France in 1942] was abandoned, this operation was the only possible way to get US troops into combat in Europe, short of shipping some to Russia. It was also the only possible way of coming close to keeping Roosevelt’s ridiculous promise to the Russians.

[…]

Nonetheless it is wrong to think that the British never had any intention of [mounting Operation] Roundup. Despite what Roosevelt and many other Americans convinced themselves, the British were, at the start of 1942, far more optimistic about the possibility of invading Europe through France in 1943 than they had been about Sledgehammer. Their studies seemed to show that Germany would only have to be weaker, not suddenly collapse, to make invasion in 1943 a realistic possibility. Realistic that is as long as the rest of the plans for training and shipping troops, building and concentrating invasion craft, and moving enough supplies to make it sustainable, all came together.

They didn’t.

For the British, the middle of 1942 revealed how little would be available in time for the middle of 1943. Even on the best assumptions of American training and preparation, there was no chance that the majority of forces for Roundup would not be British … assuming they could supply them either. In practice mid-1942 saw the Axis continue to advance on every front. Burma collapsed; the Allied position in New Guinea was under threat; the Japanese were still expanding to places like Guadalcanal; Rommel was advancing in Egypt; the Germans were advancing on the Caucasian oil fields and towards the Middle East; and more and more was needed just to keep Russia in the war. As a result British troops, shipping and supplies were continuing to flow away from Britain, not towards it.

Much of the Royal Navy was trying to save the dangerous losses caused by [US Chief of Naval Operations Admiral] King’s refusal to have convoys in American waters (too “defensive-minded” he thought.) These alone, the worst eight months of the war, were threatening to scupper Roundup. The rest was so busily deployed in the Indian and Pacific Oceans against the Japanese, or North Atlantic trying to fight supplies through to Russia (a high proportion of tanks and planes defending Moscow were British-supplied), that there was virtually nothing left in the Med to slow Rommel’s advance. The merchant ships surviving the fight across the oceans were actually more vitally needed to take men and equipment from the UK to other places than to bring in a buildup for the UK.

Nor was the American buildup going to plan. Less well-trained troops were becoming available too slowly, could not be shipped in adequate numbers anyway, and were in no condition to face German veterans. (The very best US units to go into action in 1942 – the Marines in Guadalcanal – and 1943 – the 1st Infantry and 1st Armored divisions which were actually professional troops not conscripts in North Africa – had very steep learning curves. Particularly at Kasserine. They were clearly not fit to face German veterans yet.

And American resource buildup was also not up to promises. King and MacArthur were milking supplies far beyond what had originally been agreed under “Germany first”. In practical terms they were doing so for the same reasons the British were: an immediate desperate situation had to be saved before a future ideal one could be pursued.

Nonetheless I have read all sorts of apparently serious suggestions that after North Africa was cleared, or at the very least after Sicily was cleared, an invasion of France should have happened.

Delusional.

Nigel Davies, “The ‘Invasion of France in 1943’ lunacy”, rethinking history, 2021-06-21.