The chaotic nature of the fragmentation of the Western Roman Empire makes a short recounting of its history difficult but a sense of chronology and how this all played out is going to be necessary so I will try to just hit the highlights.

First, its important to understand that the Roman Empire of the fourth and fifth centuries was not the Roman Empire of the first and second centuries (all AD, to be clear). From 235 to 284, Rome had suffered a seemingly endless series of civil wars, waged against the backdrop of worsening security situations on the Rhine/Danube frontier and a peer conflict in the east against the Sassanid Empire. These wars clearly caused trade and economic disruptions as well as security problems and so the Roman Empire that emerges from the crisis under the rule of Diocletian (r. 284-305), while still powerful and rich by ancient standards, was not as powerful or as rich as in the first two centuries and also had substantially more difficult security problems. And the Romans subsequently are never quite able to shake the habit of regular civil wars.

One of Diocletian’s solutions to this problem was to attempt to split the job of running the empire between multiple emperors; Diocletian wanted a four emperor system (the “tetrarchy” or “rule of four”) but what stuck among his successors, particular Constantine (r. 306-337) and his family (who ruled till 363), was an east-west administrative divide, with one emperor in the east and one in the west, both in theory cooperating with each other ruling a single coherent empire. While this was supposed to be a purely administrative divide, in practice, as time went on, the two halves increasing had to make do with their own revenues, armies and administration; this proved catastrophic for the western half, which had less of all of these things (if you are wondering why the East didn’t ride to the rescue, the answer is that great power conflict with the Sassanids). In any event, with the death of Theodosius I in 395, the division of the empire became permanent; never again would one man rule both halves.

We’re going to focus here almost entirely on the western half of the empire […]

The situation on the Rhine/Danube frontier was complex. The peoples on the other side of the frontier were not strangers to Roman power; indeed they had been trading, interacting and occasionally raiding and fighting over the borders for some time. That was actually part of the Roman security problem: familiarity had begun to erode the Roman qualitative advantage which had allowed smaller professional Roman armies to consistently win fights on the frontier. The Germanic peoples on the other side had begun to adopt large political organizations (kingdoms, not tribes) and gained familiarity with Roman tactics and weapons. At the same time, population movements (particularly by the Huns) further east in Europe and on the Eurasian Steppe began creating pressure to push these “barbarians” into the empire. This was not necessarily a bad thing: the Romans, after conflict and plague in the late second and third centuries, needed troops and they needed farmers and these “barbarians” could supply both. But […] the Romans make a catastrophic mistake here: instead of reviving the Roman tradition of incorporation, they insisted on effectively permanent apartness for the new arrivals, even when they came – as most would – with initial Roman approval.

This problem blows up in 378 in an event – the Battle of Adrianople – which marks the beginning of the “decline and fall” and thus the start of our “long fifth century”. The Goths, a Germanic-language speaking people, pressured by the Huns had sought entry into Roman territory; the emperor in the East, Valens, agreed because he needed soldiers and farmers and the Goths might well be both. Local officials, however, mistreated the arriving Goth refugees leading to clashes and then a revolt; precisely because the Goths hadn’t been incorporated into the Roman military or civil system (they were settled with their own kings as “allies” – foederati – within Roman territory), when they revolted, they revolted as a united people under arms. The army sent to fight them, under Valens, engaged foolishly before reinforcements could arrive from the West and was defeated.

In the aftermath of the defeat, the Goths moved to settle in the Balkans and it would subsequently prove impossible for the Romans to move them out. Part of the reason for that was that the Romans themselves were hardly unified. I don’t want to get too deep in the weeds here except to note that usurpers and assassinations among the Roman elite are common in this period, which generally prevented any kind of unified Roman response. In particular, it leads Roman leaders (both generals and emperors) desperate for troops, often to fight civil wars against each other, to rely heavily on Gothic (and later other “barbarian”) war leaders. Those leaders, often the kings of their own peoples, were not generally looking to burn the empire down, but were looking to create a place for themselves in it and so understandably tended to militate for their own independence and recognition.

Indeed, it was in the context of these sorts of internal squabbles that Rome is first sacked, in 410 by the Visigothic leader Alaric. Alaric was not some wild-eyed barbarian freshly piled over the frontier, but a Roman commander who had joined the Roman army in 392 and probably rose to become king of the Visigoths as well in 395. Alaric had spent much of the decade before 410 alternately feuding with and working under Stilicho, a Romanized Vandal, who had been a key officer under the emperor Theodosius I (r. 379-395) and a major power-player after his death because he controlled Honorius, the young emperor in the West. Honorius’ decision to arrest and execute Stilicho in 408 seems to have precipitated Alaric’s move against Rome. Alaric’s aim was not to destroy Rome, but to get control of Honorius, in particular to get supplies and recognition from him.

That pattern: Roman emperors, generals and foederati kings – all notionally members of the Roman Empire – feuding, was the pattern that would steadily disassemble the Roman Empire in the west. Successful efforts to reassert the direct control of the emperors on foederati territory naturally created resentment among the foederati leaders but also dangerous rivalries in the imperial court; thus Flavius Aetius, a Roman general, after stopping Attila and assembling a coalition of Visigoths, Franks, Saxons and Burgundians, was assassinated by his own emperor, Valentinian III in 454, who was in turn promptly assassinated by Aetius’ supporters, leading to another crippling succession dispute in which the foederati leaders emerged as crucial power-brokers. Majorian (r. 457-461) looked during his reign like he might be able to reverse this fragmentation, but his efforts at reform offended the senatorial aristocracy in Rome, who then supported the foederati leader Ricimer (half-Seubic, half-Visigoth but also quite Romanized) in killing Majorian and putting the weak Libius Severus (r. 461-465) on the throne. The final act of all of this comes in 476 when another of these “barbarian” leaders, Odoacer, deposed the latest and weakest Roman emperor, the boy Romulus Augustus (generally called Romulus Augustulus – the “little” Augustus) and what was left of the Roman Empire in the west ceased to exist in practice (Odoacer offered to submit to the authority of the Roman Emperor in the East, though one doubts his real sincerity). Augustulus seems to have taken it fairly well – he retired to an estate in Campania originally built by the late Republican Roman general Lucius Licinius Lucullus and lived out his life there in leisure.

The point I want to draw out in all of this is that it is not the case that the Roman Empire in the west was swept over by some destructive military tide. Instead the process here is one in which the parts of the western Roman Empire steadily fragment apart as central control weakens: the empire isn’t destroyed from outside, but comes apart from within. While many of the key actors in that are the “barbarian” foederati generals and kings, many are Romans and indeed (as we’ll see next time) there were Romans on both sides of those fissures. Guy Halsall, in Barbarian Migrations and the Roman West (2007) makes this point, that the western Empire is taken apart by actors within the empire, who are largely committed to the empire, acting to enhance their own position within a system the end of which they could not imagine.

It is perhaps too much to suggest the Roman Empire merely drifted apart peacefully – there was quite a bit of violence here and actors in the old Roman “center” clearly recognized that something was coming apart and made violent efforts to put it back together (as Halsall notes, “The West did not drift hopelessly towards its inevitable fate. It went down kicking, gouging and screaming”) – but it tore apart from the inside rather than being violently overrun from the outside by wholly alien forces.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Rome: Decline and Fall? Part I: Words”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2022-01-14.

December 18, 2023

QotD: A short history of the (long) Fifth Century

December 11, 2023

Roman glossary

As I continue to post QotD entries drawn from Bret Devereaux’s fascinating historical blog A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry (with Dr. Devereaux’s kind permission, I hasten to add), the number of specialized terms from the Roman Republic and Empire also expands. As some of these terms pop up in my shorter excerpts without immediate context, I think that a glossary for Rome is called for (similar to the Spartan glossary, as there’s a lot more Roman content coming up, it being Dr. Devereaux’s area of academic specialization) to help explain the terms that I think may need expansion in these excerpts from his longer posts. As usual, most of the information is drawn directly from ACOUP (often from more than one original post) and where I’ve felt the need to interpolate any additional information it will be enclosed in square brackets. Errors and misinterpretations of his original work are purely mine.

November 27, 2023

Elagabalus, the first queer or trans Roman emperor?

I guess it was inevitable that the urge to “queer” the museum or “queer” history would eventually dig up Elagabalus as an icon, as his brief reign certainly drew a lot of slander in the years that followed his death (similar to what historians wrote about Caligula or Nero … once they were safely dead):

Bust of Elagabalus in the Palazzo Nuovo – Capitoline Museums – Rome.

Photo by José Luiz Bernardes Ribeiro / CC BY-SA 4.0.

It’s not such a stretch as it may sound. As well as throwing wild parties, Elagabalus was also said to have openly flouted contemporary gender roles. The emperor is said to have also dressed as a female sex worker, “married” a male slave and acted as his “wife”, asked to be referred to as “lady” rather than “lord” and even, according to one account, begged to have a surgical vagina made by a physician.

The stories led Keith Hoskins, executive member for arts at North Herts council, to say in a statement: “Elagabalus most definitely preferred the she pronoun, and as such this is something we reflect when discussing her in contemporary times … It is only polite and respectful. We know that Elagabalus identified as a woman and was explicit about which pronouns to use, which shows that pronouns are not a new thing.”

But do we know that? Thanks to a growing awareness of more complex ideas of gender in history, and a desire to reject historical prejudices, Elagabalus has been reclaimed in recent decades as a genderqueer icon.

However, many historians disagree that the evidence is as unambiguous as the museum says. Mary Beard, formerly professor of classics at Cambridge University, directed followers on X to her latest book, titled Emperor of Rome, which opens with a lengthy discussion of the “tall stories” told about Elagabalus.

The accounts of sexual unconventionality (and extravagant cruelty) largely originate with hostile historians who wanted to win the favour of Elegabalus’s successor, Severus Alexander, and so portrayed the emperor in the worst light possible, she says. “How seriously should we treat them? Not very is the usual answer,” Beard writes, calling the stories “untruths and flagrant exaggerations”.

The Romans may not have shared current understandings of trans identity, but several of the contested accounts about Elagabalus feel remarkably modern, points out Zachary Herz, assistant professor of classics at the University of Colorado in Boulder, who has written about how we should approach the story of Elagabalus in the context of queer theory.

Asserting that Elagabalus requested female pronouns is an “astonishingly close translation” of a story written by the third-century historian Cassius Dio, says Herz. “Elagabalus is literally saying, ‘Don’t call me this word that ends in the masculine ending, call me this word that ends in the feminine’. So it’s unbelievably close to correcting someone’s pronouns.”

The problem, as he sees it, is that “I just don’t think it really happened”. “The quote-unquote biographies” written under Elagabalus’s successor are “hit pieces”, he says. “I would be inclined to read [them] as basically fictional.”

Martijn Icks, a lecturer in classics at the university of Amsterdam and author of a book about Elagabalus’s life and posthumous reputation, agrees that the stories about the emperor should be taken with “a large pinch of salt”. The same “effeminacy narrative” that has made Elagabalus a queer icon “was meant to character assassinate the Emperor, to show that he was completely unsuitable to occupy this position”, he says, adding that other so-called “bad emperors” including Nero and Caligula were described in very similar terms.

Racial prejudice also played a part, says Icks: before coming to Rome to rule it, Elagabalus was a priest in an obscure cult in Syria that venerated a black stone meteorite – a culture that would have been deeply strange to the Romans.

“And the stereotype that Romans had of Syrians … is that they were very effeminate and not real men like the Romans were.”

November 20, 2023

A Tour of the Excavations at Vindolanda

Scenic Routes to the Past

Published 4 Aug 2023This spring, Dr. Andrew Birley gave me a tour of the ongoing excavations at Vindolanda, a Roman fort near Hadrian’s Wall.

Chapters:

0:00 Welcome to Vindolanda

4:41 The wooden underworld

7:13 Layers of history

9:03 Becoming part of the story

November 14, 2023

“Like all Luttwak stories, this is probably false but totally believable”

In the latest book review from Mr. and Mrs. Psmith’s Bookshelf, John Psmith considers Edward Luttwak’s fascinating and controversial The Grand Strategy of the Roman Empire, a book I quite enjoyed reading although I think his much later The Grand Strategy of the Byzantine Empire one of his best books.

In one of the dozens of notorious interviews of Edward Luttwak that float around the internet, he’s asked how he chose the topic for his PhD dissertation. His answer is that one day at university he had a humiliating social encounter. Immediately afterwards, somebody pounced on him and asked what his dissertation was about anyway. He hadn’t even started thinking about what his topic would be, but he obviously couldn’t say that, and so instead he puffed himself up and made something up on the spot, and he did so by saying the most grandiloquent series of words one at a time like a large language model feverishly choosing the next token to maximize self importance: “The … GRAND … Strategy … … OF THE ROMAN EMPIRE!!” His interlocutor was sufficiently awed and impressed, but then he had to write the damn thing. Like all Luttwak stories, this is probably false but totally believable.1

But I’m very glad he wrote that thesis, because it was later turned into the wonderful book I’m reviewing. Now, one of the ways that the Psmiths subvert traditional gender roles is that it’s Jane, not I, who thinks about the Roman Empire every day. But this is only pretending to be a book about the Roman Empire. It’s really a book about “grand strategy” — how states can efficiently allocate scarce military, diplomatic, and financial resources to counter a variety of internal and external threats. It’s true that the examples are mainly drawn from four centuries of Roman history — starting with the Julio-Claudian dynasty and ending with the Empire losing control of Italy and Western Europe — but the analysis, and the lessons, are abstract enough that they transcend that particular context.

Luttwak believes that the state is a kind of machine for turning arable land into military power via taxation and conscription. A state that wants to maximize its survival odds can do so in three ways: (1) it can increase its “inputs”, by bringing a larger quantity of arable land under its control (so long as it avoids a commensurate increase in the threats it faces); (2) It can increase the efficiency of the machine, by extracting more grain and more labor from the people it rules, or by undertaking internal reforms to reduce the amount of potential that’s bled away by corruption and decadence; or (3) It can use its military as effectively as possible, doing more with less, killing many birds with one stone or setting up situations where a small allocation of force can tie down much larger opponents.

This third option is more or less what Luttwak means by “grand strategy,” and I think it may be the key that ties together all of Luttwak’s writing and thought. What do a book about the ancient world and a book about Cold War era coups have in common? They’re both about doing more with less, economizing force by wielding it with overwhelming brutality and efficiency. Luttwak’s coldly arithmetic view of the state is reminiscent of nothing so much as James C. Scott’s view of the world,2 but Luttwak is on the opposite team. Scott is an anarchist, Luttwak is a hard-boiled realist, and moreover he’s one with a deep aesthetic appreciation for power and violence, especially when used elegantly, like a scalpel, such that they have effects far out of proportion with their quantity.3

The history of Rome that Luttwak wants to tell is not the history of its cultural or civilizational achievements, but rather the history of how these people were so incredibly good at economizing on violence that they were able to waste a huge portion of their military and economic potential on civil wars, but still keep the lights on and the barbarians at bay. “Grand strategy” is how they accomplished that, but the strategy changed as the threats evolved and as the internal condition of the empire deteriorated. Luttwak delineates three distinct epochs — the founding of the empire under the Julio-Claudian dynasty, the rationalization of frontiers under the Antonine emperors, and the Crisis of the Third Century — and argues that each of the three featured a fundamentally different overall strategic posture on the part of Rome.

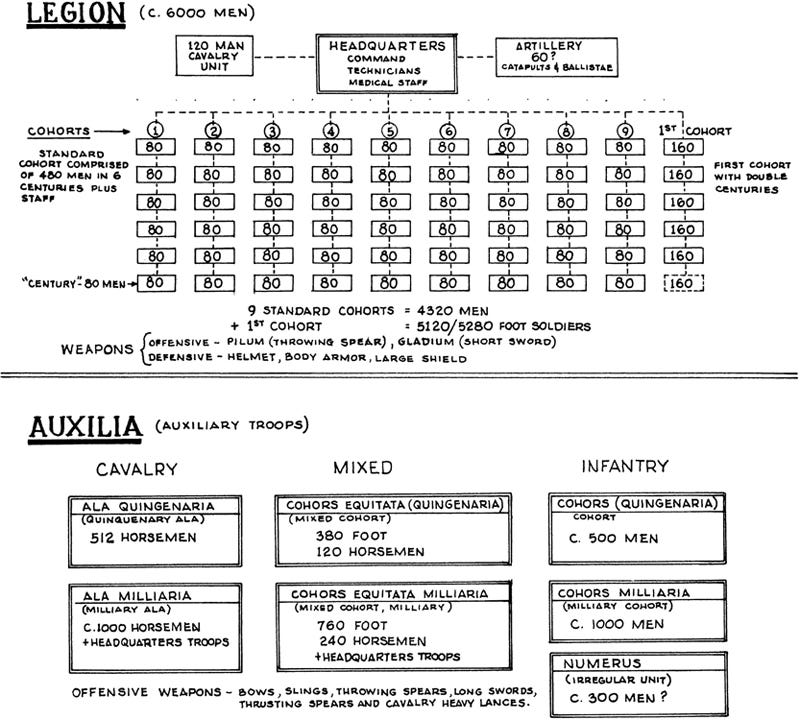

But before we get into all of that, I suppose we ought to talk about the legions. When people think of Roman military power, they usually think of the heavily-armed guys with red cloaks and horsehair plumes on their helmets. But of course they only made up a small fraction of the Roman military. We know that this has to be true because ancient armies, as much as modern armies, relied on combined-arms for their success. A legionary was a very scary kind of soldier, combining the roles of heavy infantry and combat engineer, but an army made up entirely of heavy infantry would be shredded by an opposing force of horse archers, for instance. So the Romans brought many other kinds of troops to bear: skirmishers, slingers, archers, light infantry, cavalry of their own (including mounted archers, light cavalry, and lancers with primitive barding that are a clear precursor of Medieval knights). And … almost to a man, all of these other forces were non-Roman.4 They were either mercenaries, or allied barbarians, or auxiliaries. As a kid in ancient history class I just accepted this as a fact, but reflect on it for a second and it seems very weird. This whole arrangement caused the Romans no end of trouble, so why did they do it that way?

Take the Luttwak pill and it all becomes clear: the Romans went all-in on legionaries as a way of economizing on force. The only people Rome could absolutely rely on were her citizens. The definition of a “real” Roman changed over time — at first it was only inhabitants of the city of Rome itself, later it was expanded to the surrounding countryside, and finally to all of Italy. But at every point it was a tiny fraction of the total population of the empire. Of that tiny fraction, some even smaller fraction are available to be trained as soldiers and to bear arms. What do you want those guys to be doing? The Roman answer is that you want them to be legionaries, because legionaries are not general-purpose soldiers, they’re specialists, and their specialties are: (1) besieging enemy cities, and (2) battles of attrition and annihilation.

1. Evidence that it’s false, he tells a completely different story in a different interview!

“I chose the subject because no theme in contemporary strategy was anywhere as interesting as the simple question of how Rome defended its territories (and added to them, now and then). Also, I did not want to waste my days reading the stultified & chaotically duplicative literature of ‘political science’ in which Strategy is imprisoned, when I could read instead in the often elegant, multi-lingual literature of Roman imperial studies.”

2. The zoomed-out, autistic alien robot anthropologist nature of this analysis also reminds me a bit of Vaclav Smil.

3. Wouldn’t the most elegant use of power be its deployment in such a way that it doesn’t really have to be used at all? In fact this is the main theme of Luttwak’s most recent book, The Grand Strategy of the Byzantine Empire, a sort of sequel to this one. In the same interview as in the first footnote, Luttwak summarizes the argument of that book: Byzantine strategy was based on:

“a single, paradoxical, principle: do everything possible to raise, equip and train the best possible army and navy, and then … do everything possible to use them as little as possible … every alternative was to be tried to avoid, or at least minimize the destructive ‘attrition’ combat of main forces. Instead, potential enemies were to be dissuaded, bribed, subverted, weakened by getting others to attack them, sidetracked into other ventures; if enemy forces attacked nonetheless, they were to be contained and delayed by skirmishing, feints and demonstrations while the search went on for other powers near or far willing to attack or at least threaten the enemy power; if enemy attacks persisted nonetheless, they were to be met by countering maneuvers designed to exhaust them rather than the destructive combat of main forces, the very last resort. It was not only the precious trained manpower of the empire that this strategy wanted to conserve, but also the enemy’s … because today’s enemy could become tomorrow’s ally.

4. This isn’t quite true in every period. For instance during the Punic Wars, the Romans fielded “equites“, native Roman cavalry of their own, but it fell out of fashion pretty quickly thereafter.

November 7, 2023

QotD: As we all know, medieval peasants wore ill-fitting clothes of grey and brown, exclusively

… the popular image of most ancient and medieval clothing is typically a rather drab affair, with the poor peasantry wearing mostly dirty, drab brown clothes (often ill-fitting ones) and so it might be imagined that regular folks had little need for involved textile finishing processes or dyeing; this is quite wrong. We have in essence already dispatched with the ill-fitting notion; the clothes of poor farmers, being often homespun and home-sewn could be made quite exactly for their wearers (indeed, loose fitting clothing, with lots of extra fabric, was often how one showed off wealth; lots of pleating, for instance, displayed that one could afford to waste expensive fabric on ornamentation). So it will not be a surprise that people in the past also liked to dress in pleasing colors and that this preference extended even to relatively humble peasants. Moreover, the simplest dyes and bleaching methods were often well within reach even for relatively humble people.

What we see in ancient and medieval artwork is that even the lower classes of society wore clothes that were bleached or dyed, often in bright, bold colors (in as much as dyes were available). At Rome, this extended even to enslaved persons; Seneca’s comment that legislation mandating a “uniform” for enslaved persons at Rome was abandoned for fear that they might realize their numbers, the clear implication being that it was often impossible to tell an enslaved person apart from a free person on the street in normal conditions (Sen. Clem. 1.24.1). Consequently, fulling and dyeing was not merely a process for the extremely wealthy, but an important step in the textiles that would have been worn even by every-day people.

That said, fulling and dyeing (though not bleaching) were fundamentally different from the tasks that we’ve discussed so far because they generally could not be done in the home. Instead they often required space, special tools and equipment and particular (often quite bad smelling) chemicals and specialized skills in order to practice. Consequently, these tasks tended to be done by specialist workers for whom textile production was a trade, rather than merely a household task.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Clothing, How Did They Make It? Part IVa: Dyed in the Wool”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2021-04-02.

November 2, 2023

Keeping Clean in Rome

seangabb

Published 2 Jul 2023A lecture, given in June 2023, about bathing and keeping clean in the Roman World — plus an overview of depilation and going to the toilet.

(more…)

October 17, 2023

An appropriate task for AI – reading the Herculaneum scrolls

Colby Cosh discusses the possibility of finally being able to read the carbonized scolls found in the buried remains of a wealthy Roman’s country villa in 1750:

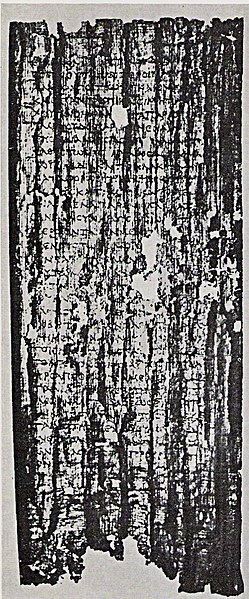

Unrolled papyrus scroll recovered from the Villa of the Papyri.

Picture published in a pamphlet called “Herculaneum and the Villa of the Papyri” by Amedeo Maiuri in 1974. (Wikimedia Commons)

From the standpoint of fragile human life, a volcanic eruption is the worst possible thing that can happen anywhere in your general vicinity, up to and probably including the detonation of a nuclear weapon.

It goes without saying that pyroclastic flows are also bad for animals or buildings or vegetation … or documents. And yet: as a consequence of the eruption of Vesuvius, there exists a near-complete library of papyrus scrolls retrieved from the buried ruins of a splendid Roman villa.

The “Villa of the Papyri” in Herculaneum was found in 1750 by farmers and was quickly subjected to archeological excavation, an art then in its infancy.

These scrolls, which today number about 1,800 in all, are often described as the only known library to have physically survived from antiquity. The problem, of course, is that they have all been burned literally to a crisp, with only a few easily readable fragments here and there.

The incinerated scrolls are so sensitive that they tend to explode into a cloud of ash at the slightest touch. Occasional attempts to unravel the scrolls — which were rolled very tightly for storage in the first place — have been made over the past 300 years; the chemist Sir Humphry Davy (1778-1829), for example, gave it a shot using newfangled stuff called chlorine. But none of these projects ever came especially close to success, and they typically involved destruction of some of the “books” in the library.

In recent years 3D imaging techniques for “reading” documents like this in a non-invasive way have been making great headway. The leader in the field is a University of Kentucky computer scientist named Brent Seales, who in 2015 led efforts to read a fragile, desiccated Hebrew Bible parchment scroll dating to the third or fourth century AD.

The text was from the book of Leviticus, and proved to be a letter-for-letter match with the Torah of today — which is a disappointment to scholars from one point of view, and a finding of awesome significance from another. (It goes without saying that this scroll came from the territory of Israel, near a kibbutz: this is a fact that would, in any other political context, be regarded as a supreme affirmation of indigeneity.)

Seales has been able to “unroll” some Herculaneum scrolls and detect the presence of inks using CT scanning, but reading the pages is a profound challenge. Roman ink was carbon-based, meaning researchers are trying to “read” traces of carbon on carbonized pages rolled up into three dimensions.

October 9, 2023

QotD: Roman views of sexual roles

There is always a temptation to emphasise the way in which the Romans are like us, a mirror held up to our own civilisation. But what is far more interesting is the way in which they are nothing like us, because it gives you a sense of how various human cultures can be. You assume that ideas of sex and gender are pretty stable, and yet the Roman understanding of these concepts was very, very different to ours. For us, I think, it does revolve around gender — the idea that there are men and there are women — and, obviously, that can be contested, as is happening at the moment. But the fundamental idea is that you are defined by your gender. Are you heterosexual or homosexual? That’s probably the great binary today.

For the Romans, this is not a binary. There’s a description in Suetonius’s imperial biography of Claudius: “He only ever slept with women.” And this is seen as an interesting foible in the way that you might say of someone, he only ever slept with blondes. I mean, it’s kind of interesting, but it doesn’t define him sexually. Similarly, he says of Galba, an upright embodiment of ancient republican values: “He only ever slept with males.” And again, this is seen as an eccentricity, but it doesn’t absolutely define him. What does define a Roman in the opinion of Roman moralists is basically whether you are — and I apologise for the language I’m now going to use — using your penis as a kind of sword, to dominate, penetrate and subdue. And the people who were there to receive your terrifying, thrusting, Roman penis were, of course, women and slaves: anyone who is not a citizen, essentially. So the binary is between Roman citizens, who are all by definition men, and everybody else.

A Roman woman, if she’s of citizen status, can’t be used willy-nilly — but pretty much anyone else can. That means that if you’re a Roman householder, your family is not just your blood relatives: it’s everybody in your household. It’s your dependents; your slaves. You can use your slaves any way you want. And if you’re not doing it, then there’s something wrong with you. The Romans had the same word for “urinate” and “ejaculate”, so the orifices of slaves — and they could be men, women, boys or girls — were seen as the equivalent of urinals for Roman men. Of course, this is very hard for us to get our heads around today.

The most humiliating thing that could happen to a Roman male citizen was to be treated like a woman — even if it was involuntary. For them, the idea that being trans is something to be celebrated would seem the most depraved, lunatic thing that you could possibly argue. Vitellius, who ended up an emperor, was known his whole life as “sphincter”, because it was said that as a young man he had been used like a girl by Tiberius on Capri. It was a mark of shame that he could never get rid of. There was an assumption that the mere rumour of being treated in this way would stain you for life; and if you enjoy it, then you are absolutely the lowest of the low.

Tom Holland, “The depravity of the Roman Peace”, UnHerd, 2023-07-07.

September 19, 2023

The end of the Western Roman Empire

Theophilus Chilton updates a review from several years ago with a few minor changes:

British archaeologist and historian Bryan Ward-Perkin’s excellent 2005 work The Fall of Rome and the End of Civilization is a text that is designed to be a corrective for the type of bad academic trends that seem to entrench themselves in even the most innocuous of subjects. In this case, Ward-Perkins, along with fellow Oxfordian Peter Heather in his book The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians, sets out to fix a glaring error which has come to dominate much of the scholarly study of the 4th and 5th centuries in the western Empire for the past few decades.

This error is the view that the western Empire did not actually “fall”. Instead, so say many latter-day historical revisionists, what happened between the Gothic victory at Adrianople in 378 AD and the abdication of Romulus Augustulus, the last western Emperor, in 476 was more of an accident, an unintended consequence of a few boisterous but well-meaning neighbors getting a bit out of hand. Challenged is the very notion that the Germanic tribes (who cannot be termed “barbarians” any longer) actually “invaded”. Certainly, these immigrants did not cause harm to the western Empire — for the western empire wasn’t actually “destroyed”, but merely “transitioned” seamlessly into the era we term the Middle Ages. Ward-Perkins cites one American scholar who goes so far as to term the resettlement of Germans onto land that formerly belonged to Italians, Hispanians, Britons, and Gallo-Romans as taking place “in a natural, organic, and generally eirenic manner”. Certainly, it is gauche among many modern academics in this field to maintain that violent barbarian invasions forcibly ended high civilization and reduced the living standards in these regions to those found a thousand years before during the Iron Age.

Ward-Perkins points out the “whys” of this historical revision. Much of it simply has to do with political correctness (which he names as such) — the notion that we cannot really say that one culture is “higher” or “better” than others. Hence, when the one replaces the other, we cannot speculate as to how this replacement made things worse for all involved. In a similar vein, many continental scholars appear to be uncomfortable with the implications that the story of mass barbarian migrations and subsequent destruction and decivilization has in the ongoing discussion about the European Union’s own immigration policy — a discussion in which many of these same academics fall on the left side of the aisle.

Yet, all of this revisionism is bosh and bunkum, as Ward-Perkins so thoroughly points out. He does this by bringing to the table a perspective that many other academics in this field of study don’t have — that of a field archaeologist who is used to digging in the dirt, finding artifacts, drawing logical conclusions from the empirical evidence, and then using that evidence to decide “what really happened”, rather than just literary sources and speculative theories. Indeed, as the author shows, across the period of the Germanic invasions, the standard of living all across Roman western Europe declined, in many cases quite precipitously, from what it had been in the 3rd century. The quality and number of manufactured goods declined. Evidence for the large-scale integrative trade network that bound the western Empire together and with the rest of the Roman world disappears. In its place we find that trade goods travelled much smaller distances to their buyers — evidence for the breakdown of the commercial world of the West. Indeed, the economic activity of the West disappeared to the point that the volume of trade in western Europe would not be matched again until the 17th century. Evidence for the decline of food production suggests that populations fell all across the region. Ward-Perkins’ discussion of the decline in the size of cattle is enlightening evidence that the degeneration of the region was not merely economic. Economic prosperity, the access of the common citizen to a high standard of living with a wide range of creature comforts, disappeared during this period.

The author, however, is not negligent in pointing out the literary and documentary evidence for the horrors of the barbarian invasions that so many contemporary scholars seem to ignore. Indeed, the picture painted by the sum total of these evidences is one of harrowing destruction caused by aggressive, ruthless invaders seeking to help themselves to more than just a piece of the Roman pie. Despite the recent scholarly reconsiderations, the Germans, instead of settling on the land given to them by various Emperors and becoming good Romans, ended up taking more and more until there was nothing left to take. As Ward-Perkins puts it,

Some of the recent literature on the Germanic settlements reads like an account of a tea party at the Roman vicarage. A shy newcomer to the village, who is a useful prospect for the cricket team, is invited in. There is a brief moment of awkwardness, while the host finds an empty chair and pours a fresh cup of tea; but the conversation, and village life, soon flow on. The accommodation that was reached between invaders and invaded in the fifth- and sixth- century West was very much more difficult, and more interesting, than this. The new arrival had not been invited, and he brought with him a large family; they ignored the bread and butter, and headed straight for the cake stand. Invader and invaded did eventually settle down together, and did adjust to each other’s ways — but the process of mutual accommodation was painful for the natives, was to take a very long time, and, as we shall see …left the vicarage in very poor shape. (pp. 82-83)

Professor Bret Devereaux discussed the long fifth century on his blog last year:

… it is not the case that the Roman Empire in the west was swept over by some destructive military tide. Instead the process here is one in which the parts of the western Roman Empire steadily fragment apart as central control weakens: the empire isn’t destroy[ed] from outside, but comes apart from within. While many of the key actors in that are the “barbarian” foederati generals and kings, many are Romans and indeed […] there were Romans on both sides of those fissures. Guy Halsall, in Barbarian Migrations and the Roman West (2007) makes this point, that the western Empire is taken apart by actors within the empire, who are largely committed to the empire, acting to enhance their own position within a system the end of which they could not imagine.

It is perhaps too much to suggest the Roman Empire merely drifted apart peacefully – there was quite a bit of violence here and actors in the old Roman “center” clearly recognized that something was coming apart and made violent efforts to put it back together (as Halsall notes, “The West did not drift hopelessly towards its inevitable fate. It went down kicking, gouging and screaming”) – but it tore apart from the inside rather than being violently overrun from the outside by wholly alien forces.

September 10, 2023

QotD: The hill people and the valley people

There’s a clichéd history of civilization which goes something like: once upon a time all human beings lived in wandering hunter-gatherer bands where everybody was directly involved in food production. Then while sojourning through a fertile river valley, some of these groups discovered agriculture. The relative predictability and reliability of farming, coupled with the much higher caloric yield per hour of labor,1 made it possible to support a denser population, and for only a portion of it to be directly involved in food production. The rest of them could become soldiers, artisans, priests, and scribes. They could develop technology, pass on their knowledge through writing, and develop complex systems of taxation, bureaucracy, and forced labour. Along the way, they made picturesque little walled farming villages […]

This is not their story. Instead it’s the story of the people who live in the hills behind that village. Without knowing anything at all about the place that picture depicts, you can probably tell me a lot about the people in those hills. Hill people are hill people, the world over. What are the odds that they’re clannish? Xenophobic? Backwards! Unusual family structures. Economically immiserated (probably due to their own paranoia and indolence). Deviant in their religious, commercial, and sexual practices. Illiterate, or at best poorly-read. They also probably talk funny. Basically they’re barbarians, but not the impressive kind who ride out of the steppe to massacre and enslave the soft city-dwellers. No, something more like living fossils — our ancestors were once like that, but then they got with the program. Well if they could do it, why don’t those hill dwellers move down here too, like normal people?2 They’re up to no good up there.

That’s certainly been the traditional view from the valleys, and there’s some truth to it, but there’s one important detail that we valley-dwellers get wrong. Far from being aboriginal holdovers of some previous phase of humanity, it’s relatively easy to determine from genetic, linguistic, and archaeological evidence that the hill people are largely descended from … the valley people!3 But … that would mean that there are people who look around at our beautiful civilization and reject its fruits — you know, art, technology, fusion cuisine, and uh … taxation, conscription, epidemic disease, corvée labour … How dare they!

You would never know it from reading the reports of the valley-bureaucrats, but the great agricultural civilizations of classical antiquity were in a near-constant state of panic over people wandering away from their farms and becoming barbarians.4 There are estimates that over the course of the empire something like twenty-five percent of the inhabitants of Roman border provinces quietly slipped across the limes for the proud life of the savage. In Ancient China, the movement was more cyclical — in times of war, or epidemic, or famine, entire villages might give up rice agriculture and vanish into the hills. Then, when the situation had stabilized, the human tide would reverse, and the hills would disgorge barbarians eager to be Sinicized (or really re-Sinicized, as their parents and grandparents had been). In both these cases and more, the boundary between “civilized” and “savage” was a great deal more porous, and the flow a great deal more bi-directional than we might realize. Like a single substance in two phases, now boiling, now condensing, changing back and forth in response to changes in the temperature.

So why then is it that hill people5 the world over have so much in common? Scott argues pretty convincingly that something like convergent cultural evolution for ungovernability is at work — that is, the qualities we stereotypically associate with backwards and barbarous peoples are precisely the traits that make one difficult to administer and tax. Some examples of this are very obvious to see — for instance physical dispersal in difficult terrain makes it harder to be surveilled, measured, or conscripted. Scott also talks a lot about the crops that hill people like to grow, and how the world over they tend to be either crops that are amenable to swiddening and don’t require irrigation, or things like tubers that mature underground and can be harvested at irregular times. Both patterns make it easy to lie about how much food you’ve planted and where, hence difficult for others to tax or control you.

What about illiteracy? Scott finds that many hill people around the world have oral legends about how they once had writing, but no longer do. Of course this is exactly what we would expect if, contrary to the usual story, the hill people are not the ancestors of the valley people, but their descendants. Yet the question remains, why give up writing? Scott posits several benefits of illiteracy: one is just that the inability to write removes any temptation to keep written records of anything, and written records are the kind of thing that can be used against you by a tax collector or an army recruiter.

But more fundamentally, a reliance on oral history and genealogy and legend is powerful precisely because these things are mutable and can be changed according to political convenience. Anybody who’s read ancient Chinese accounts of the steppe peoples or Roman discussions of Germanic barbarians has probably recoiled from the confusing profusion of tribes, peoples, and nations; the same ethnonyms popping in and out of existence over a vast area, or referring to a band of a few hundred one year and a nation of millions a decade later. Scott argues that the reason we see this is that the very notion of stable ethnic identity is a fundamentally “valley” conceit. Out in the hills or on the far wild plains, people exist in more of a quantum superposition of identities, and the nonsensical patterns you see in the histories come from imperial ethnographers feverishly making classical measurements in a double-slit experiment and trying to jam the results into a sensible form.

John Psmith, “REVIEW: The Art of Not Being Governed by James C. Scott”, Mr. and Mrs. Psmith’s Bookshelf, 2023-01-16.

1. Scott has yet another book about how this important detail of the stock story is totally false. In Scott’s telling, early agriculture produced fewer calories per hour of work than hunting and foraging. The entire increase in social complexity associated with primitive agriculture came not from a food surplus, but from the fact that it was easier to measure how much food everybody was producing and confiscate a portion of it.

2. Maybe then one of their descendants can go to Yale Law School and write a book about it.

3. Next time you’re driving through Montana, try to count how many people are transplants from New York or California.

4. Once you know this fact, you can go back and read those classical texts esoterically, and nervous panic over people defecting from civilization is practically all you will see.

5. I’ve used “hill people” throughout this review as a synecdoche for groups that have rejected a life-pattern involving settled agriculture and tax-paying, but as Scott points out there are many kind of terrain unsuitable or difficult for state administration. Marshes have historically been another magnet for those rejecting polite society, as have deserts and open plains.

September 3, 2023

The Saalburg: A Roman Fort on the German Frontier

Scenic Routes to the Past

Published 23 May 2023A brief tour of the principal buildings in the Saalburg, Germany’s most completely reconstructed Roman fort.

(more…)

August 12, 2023

The urge to compare our own culture to the declining Roman Empire

In UnHerd, Alexander Poots wants pundits to stop comparing this or that country in the West to the latter stages of the Gibbonian decline of Rome:

“The Course of Empire – Desolation” by Thomas Cole, one of a series of five paintings created between 1833 and 1836.

Wikimedia Commons.

On both sides of the Atlantic, hysterical comparisons between the collapse of the Roman Empire and the senile polities of the modern West have become the journalistic norm. Every major problem facing our society — from climate change to Covid to inflation — has received the Gibbon treatment.

There are, of course, regional variations. The British, tied by geography to Europe’s fortunes, tend to favour the definitive fall of the Western empire in AD 476. The Americans, ever fearful of an over-mighty executive, linger on the collapse of senatorial authority in 49 BC. And it is also more than a journalistic trope, with the unacknowledged legislators of our world also playing the same game. Elon Musk recently suggested that today’s baby drought is analogous to the low birth rates of Julius Caesar’s dictatorship. Marc Andreessen has compared California to Rome circa AD 250. Joe Rogan, meanwhile, is beginning to suspect that all this gender business might have a worrying ancient precedent.

Such appeals to the past are only human. The fourth word in Virgil’s Aeneid is Troiam. This is the first fact that we learn about Aeneas: he is from Troy. Virgil does not even bother to tell us his hero’s name until the 92nd line. Doubtless, the poets of Ur and Hattusha had their own Troys. And perhaps the first men who placed one mud brick upon another sang of flooded valleys, choked caves and herds that no longer ran. But Rome has been our common loss since the early Middle Ages. As Virgil looked back to Priam, so we look back to Virgil. In 1951, it was perfectly natural for W. H. Auden to compare a dying Britain with a dead Rome: “Caesar’s double-bed is warm / As an unimportant clerk / Writes I DO NOT LIKE MY WORK / On a pink official form”

But journalists and billionaires do not work in a poetic register. They deal in facts and lucre. When they say that Britain or America is following imperium Romanum down the dusty track to oblivion, they seem to be speaking literally. This is not a mistake that Virgil would have made. It is all very well to evoke Rome as an elegiac warning. But if we believe that there are concrete lessons to learn from the Roman Empire’s decline and fall, then we will have to examine the mother of cities as she really was. The results are surprising.

In AD 384, 400 years after Virgil composed his Aeneid, Quintus Aurelius Symmachus had a bridge problem. Symmachus was Urban Prefect of Rome, a role of huge responsibility. By the fourth century, the city of Rome was no longer the imperial capital of the western empire; it had been replaced in 286 by Mediolanum (modern Milan), which was a good deal closer to the empire’s febrile northern borders. But Rome remained the nation’s hearthstone. Her good governance was of the highest priority. The Urban Prefect dispensed justice, organised games, fed the mob and looked after the material fabric of the city. It was not an enviable position. One man had to keep the vast, turbulent metropolis ticking over with the minimum of rioting. Symmachus was well aware of the touchiness of the Roman pleb. His own father had been burned out of his house and chased from the city after making a catty remark of the “let them eat cake” variety during the wine shortage of 375.

The bridge problem went like this. Around 382, the emperor Gratian ordered that a new bridge be built across the Tiber. It soon became clear that construction was taking too long and costing too much. Two years later, as the project neared completion, one span collapsed. Such waste of public funds could not be ignored, and so an inquiry was launched. A specialist diver was engaged to examine the structure; he discovered that the job had been bodged. The engineers responsible for the project, Cyriades and Auxentius, were summoned to account for their failure. Each blamed the other, before Auxentius, who had been caught backfilling sections of the bridge with bales of hay, fled the city — pockets doubtless jingling with public gold.

On the face of it, this sounds like a very late Roman story: a nation once famous for its engineering prowess could no longer build a bridge across the Tiber without everything going horribly wrong. But I’m not sure that’s true. Problems arise all the time, and in themselves tell us very little about a society. What matters is the response to those problems. And Symmachus’s dispatches to the imperial court make it clear that his response was considered and comprehensive. The bridge was completed in the end, and stood for over 1,000 years until its demolition in 1484. Now think of 21st-century London: remember what happened the last time we tried to build a bridge across the Thames?

August 11, 2023

QotD: Subsistence versus market-oriented farming in pre-modern societies

Large landholders interacted with the larger number of small farmers (who make up the vast majority of the population, rural or otherwise) by looking to trade access to their capital for the small farmers’ labor. Rather than being structured by market transactions (read: wage labor), this exchange was more commonly shaped by cultural and political forces into a grossly unequal exchange whereby the small farmers gathered around the large estate were essentially the large landholder’s to exploit. Nevertheless, that exploitation and even just the existence of the large landholder served to reorient production away from subsistence and towards surplus, through several different mechanisms.

Remember: in most pre-modern societies, the small farmers are largely self-sufficient. They don’t need very many of the products of the big cities and so – at least initially – the market is a poor mechanism to induce them to produce more. There simply aren’t many things at the market worth the hours of labor necessary to get them – not no things, but just not very many (I do want to stress that; the self-sufficiency of subsistence farmers is often overstated in older scholarship; Erdkamp (2005) is a valuable corrective here). Consequently, doing anything that isn’t farming means somehow forcing subsistence farmers to work more and harder in order to generate the surplus to provide for those people who do the activities which in turn the subsistence farmers might benefit from not at all. But of course we are most often interested in exactly all of those tasks which are not farming (they include, among other things, literacy and the writing of history, along with functionally all of the events that history will commemorate until quite recently) and so the mechanisms by which that surplus is generated matter a great deal.

First, the large landholder’s farm itself existed to support the landholder’s lifestyle rather than his actual subsistence, which meant its production had to be directed towards what we might broadly call “markets” (very broadly understood). Now many ancient and even medieval agricultural writers will extol the value of a big farm that is still self-supporting, with enough basic cereal crops to subsist the labor force, enough grazing area for animals to provide manure and then the rest of the land turned over to intensive cash-cropping. But this was as much for limiting expenses to maximize profits (a sort of mercantilistic maximum-exports/minimum-imports style of thinking) as it was for developing self-sufficiency in a crisis. Note that we (particularly in the United States) tend to think of cash crops as being things other than food – poppies, cotton, tobacco especially. But in many cases, wheat might be the cash crop for a region, especially for societies with lots of urbanism; good wheat land could bring in solid returns […]. The “cash” crop might be grapes (for wine) or olives (mostly for olive oil) or any number of other necessities, depending on what the local conditions best supported (and in some cases, it could be a cash herd too, particularly in areas well-suited to wool production, like parts of medieval Britain).

Second, the exploitation by the large landholder forces the smaller farmers around him to make more intensive use of their labor. Because they are almost always in debt to the fellow with the big farm and because they need to do labor to get access to plow teams, manure, tools, or mills and because the large landholder’s land-ready-for-sharecropping is right there, the large landholder both creates the conditions that impel small farmers to work more land (and thus work more days) than their own small farms do and also creates the conditions where they can farm more intensively (both their own lands and the big farm’s lands, via plow teams, manure, etc.). Of course the large landholder then generally immediately extracts that extra production for his own purposes. […] all of the folks who aren’t small farmers looking to try to get small farmers to work harder than is in their interest in order to generate surplus. In this case, all of that activity funnels back into sustaining the large landholder’s lifestyle (which often takes place in town rather than in the countryside), which in turn supports all sorts of artisans, domestics, crafters and so on.

And so the large landholder needs the small subsistence farmers to provide flexible labor and the small subsistence farmers (to a lesser but still quite real degree) need the large landholder to provide flexibility in capital and work availability and the interaction of both of these groups serves to direct more surplus into activities which are not farming.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Bread, How Did They Make It? Part II: Big Farms”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2020-07-31.

August 4, 2023

QotD: The “knowledge base” problem in teaching history

Knowledge base. This is both over- and under-supplied in the Biz [teaching history]. If one were inclined to make efforts to remain humble, History is a good place to start, because a) it’s accessible to all, which means b) a lot of your “students” know a LOT more, about a lot more things, than you do. […]

The point is this: Even if I were an expert in that particular field (I’m not; as with Sovietology, I’m a gentleman amateur), there are zillions of people who know more of the details than I do. It seems like half the Internet can reel off, from memory, the entire command structure of the 6th Volksgrenadier regiment. Teach a “Modern Europe” class, and you’re guaranteed to have at least one of them among the studentry. Knowledge, in that sense, is over-supplied.

It’s over-supplied in another way, too. There have been tremendous recent advances in the study of, say, the Roman Empire. Computer modeling of seed-distribution patterns and asdzlsjdfjkha … sorry, my head hit the keyboard, I can’t stay awake for this stuff, but I’m sure glad someone can, because it’s important. As I understand it, there have been revolutions even in older fields like numismatics and epigraphy — you can learn a lot from coins and inscriptions, and they’re changing our understanding of some fundamental stuff (see e.g. Roman coins in Japan).

But knowledge is also under-supplied, especially from the teachers’ side. Not just “knowledge of human nature”, above, though of course that’s a biggie. Here’s a far from exhaustive list of what I was NOT taught in graduate school:

- economics

- military strategy

- ecology

- agriculture

- logistics

- Western languages

- non-Western languages

and so on. Now, some of these you’re supposed to have supplied yourself (e.g. the languages, provided you don’t need them for your specialty, and at one time I could muddle through a few), but nobody checks. Obviously nobody checks when it comes to economics, because everyone in the Biz is a Marxist, and sentence one of page one of any basic economics textbook should read “Marxism is a comprehensive crock of horseshit”, but it works that way for all the others, too. Considering that “farming” and “fighting” are two of the Three F’s that comprise “what almost all humans did, all the time, for all of recorded history”, those are some pretty goddamn big oversights … you know, if actually knowing how humans do is the point.1

Severian, “How to Teach History”, Rotten Chestnuts, 2020-12-23.

1. the third F, for the record, is “fucking”, and like the languages, you’re supposed to have acquired a working knowledge of that on your own before you arrive. Alas, that obviously didn’t work out as planned. The 40 Year Old Virgin wasn’t supposed to be a documentary, but it’s pretty much cinéma vérité in your average graduate program. Trust me: The persyn with bespoke pronouns has them because xzhey have absolutely no idea what to do with their naughty bits. When I say that a night on the town with a sailor on shore leave would cure most of these … organisms … of the majority of their problems, I mean it. Getting eggheads blued, screwed, and tattooed wouldn’t save America, but it would be a damn good start.