Michael Brendan Dougherty looks back at the UN’s intervention in Kosovo and the situation in Kosovo after more than a decade and a half:

It’s been almost 16 years since a NATO coalition banded together to defeat Serbia’s Slobodan Milošević in Kosovo. Ever since, it has been exhibit A in the case for “humanitarian intervention.” A swift short war, a thug removed from power, a series of oppressions redressed. After the hostilities ceased, Kosovo’s government was overseen by the United Nations, and declared full independence from Serbia in 2008.

In the meantime, the U.N. bungled possibly the easiest show-trial in world history, letting Milošević score a lot of points from the stand as the trial dragged on longer than it took F.D.R. to declare war on Germany, mobilize a few million men, and beat Hitler. Milošević died of a heart attack in prison before his trial finished. NATO troops are in Kosovo, a decade and a half after the “short” 78-day campaign.

What’s the political scene like in liberated Kosovo? Well, here’s a story. Last week Aleksandar Jablanovic, an ethnic Serb who served in the cabinet as minister of communities, was sacked by Prime Minister Isa Mustafa, in order to appease ethnic Albanians who were planning riotous protests against him. Kosovars threw rocks at government buildings. About 170 people were injured in the clash between protesters and police.

What did Jablanovic do to cause the unrest? He had described a group of Albanians as “savages” in January. Why? Because they had blocked (with the threat of violence) the route of Serbian Christians making a traditional pilgrimage to a monastery in Western Kosovo.

Sounds unpleasant, right? It gets worse. Unemployment in Kosovo is around 45 percent. (That’s not a typo.) The electricity is very unreliable, and Kosovars often don’t pay their electricity bills to the state. The government is considering canceling all debts that citizens owe to the government, to rebuild trust (and popularity) and start putting services on a firmer footing. About a third of Kosovars live on less than $2 a day.

[…]

But there’s also no doubt that Kosovo should serve as a permanent warning against the idea that humanitarian interventions are easy. The bombing was a perfect example of the moral hazard involved in “Responsibility to Protect” interventions. The roar of NATO jets so raised the stakes for Serbian forces and for Milošević, that Serbians killed five times as many people after the intervention became a fait accompli than they had before that time, under the theory that rubble makes less trouble.

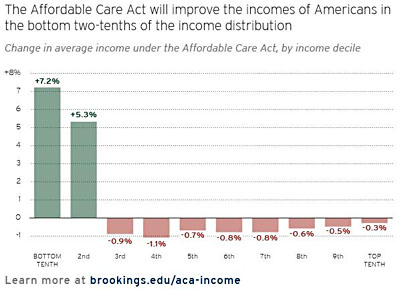

Here’s an interesting chart that follows up on

Here’s an interesting chart that follows up on