Marc Edge discusses how Canada’s legacy media joined together in a virtual suicide-pact to force Google and Facebook to give them millions in unearned revenue:

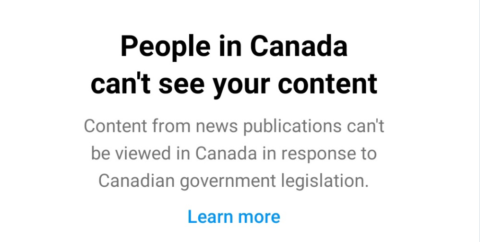

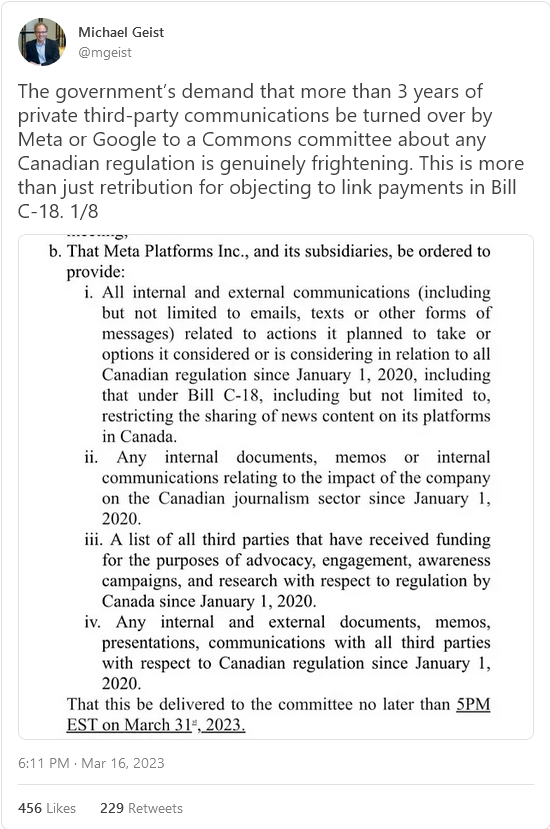

The best-laid plans of Canada’s biggest media owners went badly awry this summer, when Meta began blocking news across the country on its social media networks Facebook and Instagram in response to the Online News Act passed in June. Newspaper publishers lobbied the federal government relentlessly to force Google and Meta to compensate them for supposedly “stealing” their news stories by carrying links to them. But instead of bringing them hundreds of millions of dollars a year from the digital giants, as a similar law has in Australia, their campaign backfired badly in what has been described as “a massive policy blunder“, and “the most spectacular legislative failure in Canada’s living political memory“.

Not only will publishers not be getting any money from Meta, they likely won’t get any from Google either, as they have threatened to similarly block news in Canada when the law comes into effect in December. Ironically, publishers will instead lose millions instead, as the agreements they already have with at least Meta will be cancelled, and probably those with Google as well. The knock-on effect makes it a triple-whammy when you also consider the traffic that news media will lose to their websites from the platforms. Worst affected will be online-only publications which have depended on that traffic to build an audience. Most did not want the Online News Act and many spoke out against it, but they were drowned out by the newspaper lobby led by industry association News Media Canada. It is dominated by the country’s two largest chains, which are now owned by a private equity firm and US hedge funds.

The Online News Act is the second in a series of bills designed to regulate the Internet, which, when taken together, include many of the same elements as the UK’s omnibus Digital Markets, Competition and Consumers Bill now before Parliament. An Online Streaming Act passed in April will tax and regulate digital video services in Canada, which are mostly owned by U.S. companies such as Netflix, Disney, and Amazon. A so-called Online Harms Act designed to combat hate speech and online bullying was introduced in 2021 but died on the order paper with an election call. It was criticised by civil libertarians for potentially prohibiting otherwise lawful speech and was thus being revised, but so far it has not been re-introduced. Legislation aimed at increasing online privacy and consumer rights is also planned.

One of these things, on closer scrutiny, is not quite like the other ones, and a realisation is growing in Canada that the government may have been co-opted in its enthusiasm to regulate the Internet to participate in what has been called a “shakedown” of the digital giants. Canada’s news media have literally been on the dole for the past five years since they lobbied the government for a five-year $595-million bailout that expires next spring. This has prompted publishers to adopt Rupert Murdoch’s successful strategy in Australia of persuading the government to force the digital giants to share their advertising revenues with newspapers.

Canadian publishers lobbied for the Online News Act in part by running blank front pages for a day and also spiked several opinion articles by academics that had been accepted for publication by editors. Canada has long had one of the free world’s highest levels of media ownership concentration, along with Australia. It went to another level in 2000 with the “convergence” of newspaper and television ownership, against which Canada had no regulatory safeguards, unlike most other countries. The multimedia business model collapsed with the 2008-09 recession, when advertising revenues dropped sharply, and Canada’s news media have been lurching from bad to worse ever since. The country’s largest newspaper chain, Postmedia Network, was acquired out of bankruptcy in 2010 by a consortium of US hedge funds which had bought much of its previous owner’s high-interest debt on the bond market for pennies on the dollar. They have since taken more than $500 million out of the company in debt payments. The country’s second-largest chain, Torstar, was bought from its owning families at the outset of the pandemic in 2020 by private equity firm NordStar Capital, which has been similarly stripping the company with closures, redundancies, and asset sales.