In 1981, the social scientist Mancur Olson published his magisterial The Rise and Decline of Nations: Economic Growth, Stagflation, and Social Rigidities. Olson had already won acclaim for The Logic of Collective Action, which explained why some groups received an outsize slice of the political pie. In his new book, Olson turned to the question of why nations fail. His thesis: nations lost dynamism when insiders managed to stack the rules against disruptive outsiders.

Stable societies with unchanged boundaries, Olson observed, “tend to accumulate more collusions and organizations for collective action over time.” Instead of accepting rules that encourage overall growth, these collusive organizations — trade groups and labor unions were paradigmatic examples — fight to keep what they have, slowing down “a society’s capacity to adopt new technologies and to reallocate resources in response to changing conditions,” thus reducing economic efficiency. Decline follows.

Olson pointed to Japanese stagnation under the Tokugawa shogunate, when, “before Admiral Perry’s gunboats appeared in 1854, the Japanese were virtually closed off from the international economy.” Ruling Japanese society, he writes, “were any number of powerful za, or guilds, and the shogunate or the daimyo often strengthened them by selling them monopoly rights.” The guilds “fixed prices, restricted production and controlled entry in essentially the same way as cartelistic organization elsewhere.”

A second example: Great Britain, “the major nation with the longest immunity from dictatorship, invasion and revolution” and, consequently, Olson explained, suffering “this century a lower rate of growth than other large, developed democracies.” In Olson’s view, the weak performance resulted from limits on change established by a “powerful network of special-interest organizations,” which included labor unions, industrial groups, and aristocratic cliques. By the 1970s, after the conservative government of Edward Heath fell in a losing battle with striking miners, many deemed Britain ungovernable. Olson contrasted the British situation with that of postwar Germany and Japan, where the chaos and destruction of wartime defeat wiped away established industrial and retail groups, leaving the field open to newcomers like Soichiro Honda or the Albrecht family (creators of international supermarket giant Aldi), who could work economic magic.

The word “ungovernable” was also used to describe New York in the 1960s and 1970s, when Mike Quill’s transit union ran roughshod over Mayor John Lindsay’s attempts to control public-sector wage growth. New York was a long-established city with lots of political collusion. The old Tammany Hall could broker deals to keep Gotham going, but Lindsay’s successor, Abe Beame, proved too weak to resist any special interest that wanted more spending or government favors. New York’s spending kept rising even as public services worsened, until bankruptcy loomed and public power wound up in the hands of the unelected Municipal Assistance Corporation. Thankfully, New York reformed itself economically, at least to some extent, under Mayors Rudolph Giuliani and Michael Bloomberg, as Britain did under Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher. Sufficiently strong leaders can buck entrenched insiders.

Edward L. Glaeser, “How to Fix American Capitalism”, City Journal, 2020-12-13.

March 30, 2021

QotD: Static societies and disruptive outsiders

February 2, 2021

The History of Hollywood

The Cynical Historian

Published 3 Sep 2020This episode is about the history of Hollywood, and it’s quite a long one. This is part 9 in a long running series about California history.

————————————————————

references:

Bernard F. Dick, Engulfed: The Death of Paramount Pictures and the Birth of Corporate Hollywood (Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky, 2001). https://amzn.to/3f2Yb0SHollywood’s America: United States History Through its Films, eds. Mintz, Steven and Randy Roberts (St. James, N.York: Brandywine Press, 1993). https://amzn.to/2tZIoJT

Richard Slotkin, Gunfighter Nation: The Myth of the Frontier in Twentieth-Century America (New York: Atheneum Books, 1992). https://amzn.to/2KX0jI2

Kevin Starr, Inventing the Dream: California through the Progressive Era, (Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press, 1985). https://amzn.to/2VPTbVX

————————————————————

Support the channel through PATREON: https://www.patreon.com/CynicalHistorian

or by purchasing MERCH: teespring.com/stores/the-cynical-hist…LET’S CONNECT:

Twitch: https://www.twitch.tv/cynicalhistorian

Discord: https://discord.gg/Ukthk4U

Twitter: https://twitter.com/Cynical_History

Subreddit: https://www.reddit.com/r/CynicalHistory/————————————————————

Wiki: By 1912, major motion-picture companies had set up production near or in Los Angeles. In the early 1900s, most motion picture patents were held by Thomas Edison’s Motion Picture Patents Company in New Jersey, and filmmakers were often sued to stop their productions. To escape this, filmmakers began moving out west to Los Angeles, where attempts to enforce Edison’s patents were easier to evade. Also, the weather was ideal and there was quick access to various settings. Los Angeles became the capital of the film industry in the United States. The mountains, plains and low land prices made Hollywood a good place to establish film studios.

Director D. W. Griffith was the first to make a motion picture in Hollywood. His 17-minute short film In Old California (1910) was filmed for the Biograph Company. Although Hollywood banned movie theaters — of which it had none — before annexation that year, Los Angeles had no such restriction. The first film by a Hollywood studio, Nestor Motion Picture Company, was shot on October 26, 1911. The H. J. Whitley home was used as its set, and the unnamed movie was filmed in the middle of their groves at the corner of Whitley Avenue and Hollywood Boulevard.

The first studio in Hollywood, the Nestor Company, was established by the New Jersey–based Centaur Company in a roadhouse at 6121 Sunset Boulevard (the corner of Gower), in October 1911. Four major film companies – Paramount, Warner Bros., RKO, and Columbia – had studios in Hollywood, as did several minor companies and rental studios. In the 1920s, Hollywood was the fifth-largest industry in the nation. By the 1930s, Hollywood studios became fully vertically integrated, as production, distribution and exhibition was controlled by these companies, enabling Hollywood to produce 600 films per year.

Hollywood became known as Tinseltown and the “dream factory” because of the glittering image of the movie industry. Hollywood has since become a major center for film study in the United States.

————————————————————

Hashtags: #history #Hollywood #California

December 16, 2020

QotD: Distorting the history of America’s “Gilded Age”

We study history to learn from it. If we can discover what worked and what didn’t work, we can use this knowledge wisely to create a better future. Studying the triumph of American industry, for example, is important because it is the story of how the United States became the world’s leading economic power. The years when this happened, from 1865 to the early 1900s, saw the U.S. encourage entrepreneurs indirectly by limiting government. Slavery was abolished and so was the income tax. Federal spending was slashed and federal budgets had surpluses almost every year in the late 1800s. In other words, the federal government created more freedom and a stable marketplace in which entrepreneurs could operate.

To some extent, during the late 1800s — a period historians call the “Gilded Age” — American politicians learned from the past. They had dabbled in federal subsidies from steamships to transcontinental railroads, and those experiments dismally failed. Politicians then turned to free markets as a better strategy for economic development. The world-dominating achievements of Cornelius Vanderbilt, James J. Hill, John D. Rockefeller, and Charles Schwab validated America’s unprecedented limited government. And when politicians sometimes veered off course later with government interventions for tariffs, high income taxes, anti-trust laws, and an effort to run a steel plant to make armor for war — the results again often hindered American economic progress. Free markets worked well; government intervention usually failed.

Why is it, then, that for so many years, most historians have been teaching the opposite lesson? They have made no distinction between political entrepreneurs, who tried to succeed through federal aid, and market entrepreneurs, who avoided subsidies and sought to create better products at lower prices. Instead, most historians have preached that many, if not all, entrepreneurs were “robber barons”. They did not enrich the U.S. with their investments; instead, they bilked the public and corrupted political and economic life in America. Therefore, government intervention in the economy was needed to save the country from these greedy businessmen.

Burton W. Folsum, “How the Myth of the ‘Robber Barons’ Began — and Why It Persists”, Foundation for Economic Education, 2018-09-21.

December 12, 2020

Trains and Oil | California History [ep.8]

The Cynical Historian

Published 4 Jul 2019After a long hiatus, here is the return of the History of California series. For those who haven’t seen the previous episodes, here’s the playlist: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list…

Today we’re going over the history of transcontinental railroads, monopolistic practices, and crude oil production in California.

————————————————————

references:

eds. Richard Francaviglia and David Narrett, Essays on the Changing Images of the Southwest (Arlington: University of Texas at Arlington, 1994). https://amzn.to/2JwNiHkWilliam H. Goetzmann, Army Exploration in the American West, 1803-1863, new ed. (1959; Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 1979). https://amzn.to/2K8tslY

Paul Sabin, Crude Politics: The California Oil Market, 1900-1940 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005). https://amzn.to/2W16gtt

Jules Tygiel, The Great Los Angeles Swindle: Oil, Stocks, and Scandal During the Roaring Twenties (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996). https://amzn.to/2ASH7Z0

Richard White, Railroaded: The Transcontinentals and the Making of Modern America (New York: W.W. Norton, 2011). https://amzn.to/2zkURO3

————————————————————

Support the channel through PATREON:

https://www.patreon.com/CynicalHistorianLET’S CONNECT:

Discord: https://discord.gg/Ukthk4U

Twitter: https://twitter.com/Cynical_History

————————————————————

Wiki: The history of the Southern Pacific stretches from 1865 to 1998. For the main page, see Southern Pacific Transportation Company; for the former holding company, see Southern Pacific Rail Corporation. The Southern Pacific was represented by three railroads. The original company was called Southern Pacific Railroad, the second was called Southern Pacific Company and the third was called Southern Pacific Transportation Company. The third Southern Pacific railroad, the Southern Pacific Transportation Company, is now operating as the current incarnation of the Union Pacific Railroad.The story of oil production in California began in the late 19th century. In 1903, California became the leading oil-producing state in the US, and traded the number one position back-and forth with Oklahoma through the year 1930. As of 2012, California was the nation’s third most prolific oil-producing state, behind only Texas and North Dakota. In the past century, California’s oil industry grew to become the state’s number one GDP export and one of the most profitable industries in the region. The history of oil in the state of California, however, dates back much earlier than the 19th century. For thousands of years prior to European settlement in America, Native Americans in the California territory excavated oil seeps. By the mid-19th century, American geologists discovered the vast oil reserves in California and began mass drilling in the Western Territory. While California’s production of excavated oil increased significantly during the early 20th century, the accelerated drilling resulted in an overproduction of the commodity, and the federal government unsuccessfully made several attempts to regulate the oil market.

————————————————————

Hashtags: #history #California #trains #oil

October 29, 2020

War, Cinema, and Cheese! | BETWEEN 2 WARS: ZEITGEIST! | E.01 – Harvest 1918

TimeGhost History

Published 28 Oct 2020War, poverty, and disease continue to pummel the word in the wake of the Great War. But still, humanity carries on, not only surviving but creating a host of futuristic opportunities in the arts, the economy, and … cheese.

Join us on Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/TimeGhostHistory

Hosted by: Indy Neidell

Written by: Indy Neidell, Francis van Berkel, and Spartacus Olsson.

Director: Astrid Deinhard

Producers: Astrid Deinhard and Spartacus Olsson

Executive Producers: Astrid Deinhard, Indy Neidell, Spartacus Olsson, Bodo Rittenauer

Creative Producer: Maria Kyhle

Post-Production Director: Wieke Kapteijns

Research by: Indy Neidell, Francis van Berkel, and Spartacus Olsson.

Archive Research: Daniel Weiss

Edited by: Daniel Weiss

Sound design: Marek KamińskiColorizations:

Daniel Weiss – https://www.facebook.com/TheYankeeCol…

(BlauColorizations) – https://www.instagram.com/blaucolorizations

Dememorabilia – https://www.instagram.com/dememorabilia/Sources:

From the Noun Project:

iron cross By Souvik Maity, IN

poverty By Phạm Thanh Lộc, VN

Skull_51748Soundtracks from Epidemic Sound:

– “One More for the Road” – Golden Age Radio

– “Dark Shadow” – Etienne Roussel

– “Not Safe Yet” – Gunnar Johnsen

– “Rememberance” – Fabien Tell

– “Last Point of Safe Return” – Fabien Tell

– “Steps in Time” – Golden Age Radio

– “What Now” – Golden Age Radio

– “Sunday Worship” – Radio Night

– “Astray” – Alec Slayne

– “Break Free” – Fabien TellArchive by Screenocean/Reuters https://www.screenocean.com.

A TimeGhost chronological documentary produced by OnLion Entertainment GmbH.

From the comments:

TimeGhost History

1 day ago

Welcome back to Between Two Wars! Strap in for what is going to be an exciting ride through the massive cultural, social, economic, and technological shifts that take place after the Great War. We can’t guarantee this will always be a positive tale. These changes entail plenty of fear and suffering, and even ‘fun’ things like the Jazz Age have their darker sides.But that doesn’t alter the fact that the interwar era is a time of promise where people envision modern futures to replace old pasts. There is everything to play for in this brave new world and a vision of progress all around in politics, culture, food, and more.

September 18, 2020

From innovation to absolutism — English inventors and the Divine Right of Kings

In the latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes looks at how innovations during the late Tudor and Stuart eras sometimes bolstered the monarchy in its financial battles with Parliament (which, in turn, eventually led to actual battles during the English Civil War):

King Charles I and Prince Rupert before the Battle of Naseby 14th June 1645 during the English Civil War.

19th century artist unknown, from Wikimedia Commons.

The various schemes that innovators proposed — from finding a northeast passage to China, to starting a brass industry, to colonising Virginia, or boosting the fish industry by importing Dutch salt-making methods — all promised to benefit the public. They were to support the “common weal”, or commonwealth. And to a certain extent, many projects did. The historian Joan Thirsk did much pioneering work in the 1970s to trace the impact of various technological or commercial projects, revealing that even something as mundane as growing woad, for its blue dye, could have a dramatic impact on local economies. With woad, the income of an ordinary farm labouring household might be almost doubled, for four months in the year, by employing women and children. In the late 1580s, the 5,000 or so acres converted to woad-growing in the south of England likely employed about 20,000 people. That may seem small today, but at a time when the population of a typical market town was a paltry 800 people, even a few hundred acres of woad being cultivated here or there might draw in workers from across the whole region. In the mid-sixteenth century, even the entire population of London had only been about 50-70,000. As Thirsk discovered, innovative projectors also sometimes fulfilled their other public-spirited promises, for example by creating domestic substitutes for costly imported goods, or securing the supplies of strategic resources.

But the ideal of benefiting the commonwealth could also, all too frequently, be elided with serving the interests of the Crown. Projectors might promise the monarch a direct share of an invention’s profits, or that a stimulated industry would result in higher income from tariffs or excise taxes. Increasingly, they proposed schemes that were almost entirely focused on maximising state revenue, with little evidence of new technology. They identified “abuses” in certain industries — at this remove, it’s difficult to tell if these justifications were real — and asked for monopolies over them in order to “regulate” them, then making money by selling licences. Last week I mentioned patents over alehouses, and on playing cards. They also offered to increase the income from the Crown’s property, for example by finding so-called “concealed lands” — lands that had been seized during the Reformation, but which through local resistance or corruption had ostensibly not been paying their proper rents. The projectors would take their share of the money they identified as “missing”. And they proposed enforcing laws, especially if the punishments involved levying fines or confiscating property. The projectors offered to find the lawbreakers and prosecute them, after which they’d take their share of the financial punishments.

Projectors thus came to present themselves as state revenue-raisers and enforcers, circumventing all of the traditional constraints on the monarch’s money and power. They provided an alternative to Parliaments, as well as to city corporations and guilds, in raising money and propagating their rule. Taking it a step further, projectors offered the tantalising possibility that kings like James I and Charles I might rule through proclamation and patents alone, without having to answer to anybody. They thus experimented with absolutism for much of 1610-40, only occasionally being forced to call Parliament for as briefly as possible when the pressing financial demands of war intervened.

In the process, with the growing multitude of projects — a few bringing technological advancement, but many merely lining the pockets of courtier and king — the designation “projector” became mud. It was as if, today, the Queen were to use her prerogative to grant a few of her courtiers monopolies on collecting all traffic fines, or litter penalties, to be rewarded solely on commission. Or if she were to award an unscrupulous private company the right to award all alcohol-selling licences (perhaps on the basis that underage drinking was becoming common). The country would soon be awash with hidden speed cameras and incognito litter wardens, and the price of alcohol would go through the roof. The people responsible would not be popular. A recent book by economic historian Koji Yamamoto meticulously charts the changing public perceptions of projects, describing the ways in which innovators then struggled, for decades, to regain the public’s trust.

September 5, 2020

Beginning the transition from personal rule to the modern bureaucratic state

Anton Howes discusses some of the issues late Medieval rulers had which in some ways began the ascendency of our modern nation state with omnipresent bureaucratic oversight of everyone and everything:

… the bureaucratic state of today, with its officials involving themselves with every aspect of modern life, is a relatively recent invention. In a world without bureaucracy, when state capacity was relatively lacking, it’s difficult to see what other options monarchs would have had. Suppose yourself transported to the throne of England in 1500, and crowned monarch. Once you bored of the novelty and luxuries of being head of state, you might become concerned about the lot of the common man and woman. Yet even if you wanted to create a healthcare system, or make education free and universal to all children, or even create a police force (London didn’t get one until 1829, and the rest of the country not til much later), there is absolutely no way you could succeed.

King James I (of England) and VI (of Scotland)

Portrait by Daniel Myrtens, 1621 from the National Portrait Gallery via Wikimedia Commons.For a start, you would struggle to maintain your hold on power. Fund schools you say? Somebody will have to pay. The nobles? Well, try to tax them — in many European states they were exempt from taxation — and you might quickly lose both your throne and your head. And supposing you do manage to tax them, after miraculously stamping out an insurrection without their support, how would you even begin to go about collecting it? There was simply no central government agency capable of raising it. Working out how much people should pay, chasing up non-payers, and even the physical act of collection, not to mention protecting that treasure once collected, all takes substantial manpower. Not to mention the fact that the collecting agents will likely siphon most of it off to line their own pockets.

[…]

It was not until 1689, when there was a coup, that an incoming ruler allowed the English parliament to sit whenever it pleased. Before that, it was convened only at the whim of the ruler, and dispersed even at the slightest provocation. In 1621, for example, when James I was planning to marry his heir to a Spanish princess, Parliament sent him a petition asserting their right to debate the matter. Upon hearing of it, he called for the official record of parliamentary proceedings, personally ripped out the page with the offending vote, and promptly dissolved the Parliament. The downside, of course, was that James could not then acquire any parliamentary subsidies.

Ruling was thus an intensely personal affair, of making deals and finding ways to circumvent deals you had inherited. Increasing your capabilities as a ruler – state capacity – was thus no easy task, as the typical ruler was stuck in an essentially medieval equilibrium. Imposing a policy costs money, but raising money involves imposing policy. Breaking out of this chicken-and-egg problem took centuries of canny leadership. The rulers who achieved it most would today seem hopelessly corrupt.

To gain extra cash without interference from Parliament, successive monarchs first asserted and then abused their ancient prerogative rights to grant monopolies over trades and industries. They eventually granted them to whomever was willing to pay, establishing monopolies over industries like gambling cards or alehouses under the guise of regulating unsavoury activities. They also sold off knighthoods and titles, and in 1670 Charles II even made a secret deal with the French that he would convert to Catholicism and attack the Protestant Dutch, all in exchange for cash. Anything to not have to call a potentially pesky Parliament. At times, the most effective rulers even resembled mob bosses. Take Elizabeth I’s anger when a cloth-laden merchant fleet bound for an Antwerp fair in 1559 was allowed to depart. Her order to stop them had not arrived in time, thus preventing her from extracting “loans” from the merchants while she still had their goods within her power.

August 22, 2020

John Cabot’s patent monopoly grant and the rise of the modern corporation

In the latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes traces the line of descent of modern corporate structures from the patent granted to John Cabot to explore (and exploit) a trade route to China:

The replica of John Cabot’s ship Matthew in Bristol harbour, adjacent to the SS Great Britain.

Photo by Chris McKenna via Wikimedia Commons.

I discussed last time [linked here] how the use of patent monopolies came to England in the sixteenth century. Since then, however, I’ve developed a strong hunch that the introduction of patent monopolies may also have played a crucial role in the birth of the business corporation. I happened to be reading Ron Harris’s new book, Going the Distance, in which he stresses the unprecedented constitutions of the Dutch and English East India Companies — both of which began to emerge in the closing years of the sixteenth century. Yet the first joint-stock corporation, albeit experimental, was actually founded decades earlier, in the 1550s. Harris mentions it as a sort of obscure precursor, and it wasn’t terribly successful, but it stood out to me because its founder and first governor was also one of the key introducers of patent monopolies to England: the explorer Sebastian Cabot.

As I mentioned last time, Cabot was named on one of England’s very first patents for invention — though we’d now say it was for “discovery” — in 1496. An Italian who spent much of his career serving Spain, he was coaxed back to England in the late 1540s to pursue new voyages of exploration. Indeed, he reappeared in England at the exact time that patent monopolies for invention began to re-emerge, after a hiatus of about half a century. In 1550, Cabot obtained a certified copy of his original 1496 patent and within a couple of years English policymakers began regularly granting other patents for invention. It started as just a trickle, with one 1552 patent granted to to some enterprising merchant for introducing Norman glass-making techniques, and a 1554 patent to the German alchemist Burchard Kranich, and in the 1560s had developed into a steady stream.

Yet Cabot’s re-certification of his patent is never included in this narrative. It’s a scarcely-noted detail, perhaps because he appears not to have exploited it. Or did he? I think the fact of his re-certification — a bit of trivia that’s usually overlooked — helps explain the origins of the world’s first joint-stock corporation.

Corporations themselves, of course, were nothing new. Corporate organisations had existed for centuries in England, and indeed throughout Europe and the rest of the world: officially-recognised legal “persons” that might outlive each and any member, and which might act as a unit in terms of buying, selling, owning, and contracting. Cities, guilds, charities, universities, and various religious organisations were usually corporations. But they were not joint-stock business corporations, in the sense of their members purchasing shares and delegating commercial decision-making to a centralised management to conduct trade on their behalves. Instead, the vast majority of trade and industry was conducted by partnerships of individuals who pooled their capital without forming any legally distinct corporation. Shares might be bought in a physical ship, or even in particular trading voyages, but not in a legal entity that was both ongoing and intangible. There were many joint-stock associations, but they were not corporations.

And to the extent that some corporations in England were related to trade, such as the Company of Merchant Adventurers of London, or the Company of Merchants of the Staple, they were not joint-stock businesses at all. They were instead regulatory bodies. These corporations were granted monopolies over the trade with certain areas, or in certain commodities, to which their members then bought licenses to trade on their own account. Membership fees went towards supporting regulatory or charitable functions — resolving disputes between members, perhaps supporting members who had fallen on hard times, and representing the interests of members as a lobby group both at home and abroad — but not towards pooling capital for commercial ventures. The regulated companies were thus more akin to guilds, or to modern trade unions or professional associations, rather than firms. Members were not shareholders, but licensees who used their own capital and were subject to their own profits and losses.

Before the 1550s, then, there had been plenty of unincorporated business associations that were joint-stock, and even more unincorporated associations that were not joint-stock. There had also been a few trade-related corporations that were not joint-stock. Sebastian Cabot’s innovation was thus to fill the last quadrant of that matrix: he created a corporation that would be joint-stock, in which a wide range of shareholders could invest, entrusting their capital to managers who would conduct repeated voyages of exploration and trade on their behalves.

August 7, 2020

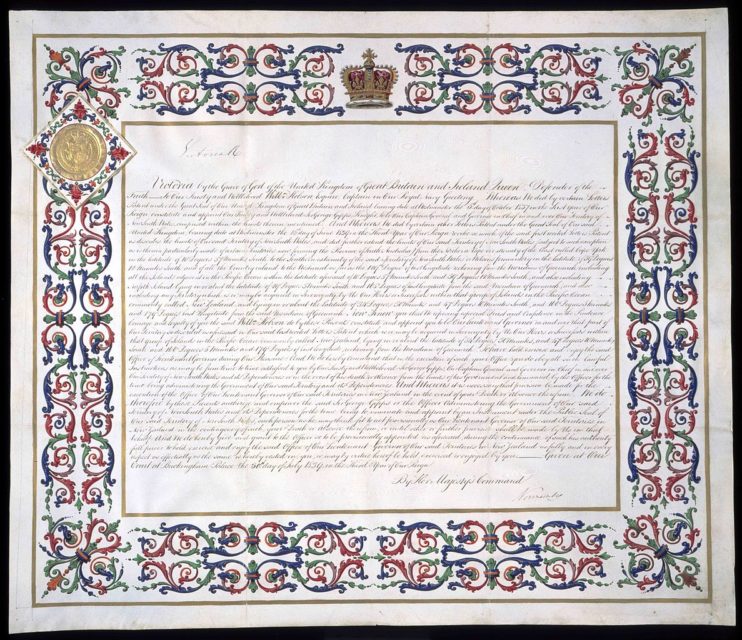

From Medieval Letters Patent to our modern patents, by way of Venice

In the latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes traces the lines of descent from the Letters patent of the Middle Ages, through Venetian legal innovations, to what began to resemble our modern patent system:

Letters Patent Issued by Queen Victoria, 1839

On 15 June 1839 Captain William Hobson was officially appointed by Queen Victoria to be Lieutenant Governor General of New Zealand. Hobson (1792 – 1842) was thus the first Governor of New Zealand. This position was renamed in 1907 as “Governor General”. Hobson arrived in New Zealand in late January 1840, and oversaw the signing of te Tiriti o Waitangi only a few days later. By the end of 1840, New Zealand became a colony in its own right and Hobson moved the capital of the colony from the Bay of Islands to Auckland. He served as Governor until his death in 1842 after he suffered a stroke at the age of 49.

Constitutional Records group of Archives NZ via Wikimedia Commons.

Patents for invention — temporary monopolies on the use of new technologies — are frequently cited as a key contributor to the British Industrial Revolution. But where did they come from? We typically talk about them as formal institutions, imposed from above by supposedly wise rulers. But their origins, or at least their introduction to England, tell a very different story.

England’s monarchs had long used their prerogative powers to grant special dispensations by letters patent — that is, orders from the monarch that were open for all the public to see (think of the word patently, from the same root, which means openly or clearly). For the most part, such public proclamations had been used to grant titles of nobility, or to appoint people to positions in various official hierarchies — legal, religious, and governmental. And, of course, letters patent could be used to promote the introduction of new technologies.

[…]

Monopolies in general, of course, over particular trades or industries had been granted for centuries, by rulers all across Europe. They granted such privileges to groups of merchants, artisans, and city-dwellers, giving them rights to organise and regulate their own activities as guilds or as city corporations. Inherent to all such charters was the ability of the in-group to restrict competition from outsiders, at least within the confines of their city. And the ruler, in exchange for granting such privileges, typically received a share of the guild’s or corporation’s revenues. But such monopolies were very rarely given to individuals. When they were, it was often so unpopular as to be almost immediately overturned. And they were rarely used to encourage innovation.

With one exception: Italy. Throughout the fifteenth century, some Italian city guilds had begun to forbid their members from copying newly-invented patterns for silk and woollen cloth, effectively granting a monopoly over those patterns to the individual inventors. In Venice, a 50-year monopoly was granted in 1416 to one Franciscus Petri, of Rhodes, to introduce superior fulling mills. In Florence, the famous architect and engineer Filippo Brunelleschi was granted a monopoly in 1421 for a vessel he designed for transporting heavy loads of marble, in exchange for revealing the secrets of his design. The printing press was also introduced to Venice using such a privilege, with a 5-year monopoly granted in 1469 to Johannes of Speyer, though he died only a few months after receiving it. And these ad hoc grants were made with increasing frequency, such that in 1474 Venice legislated to make them more systematic, declaring that 10-year monopolies could be obtained for all new technologies, either invented or imported (though it continued to also grant ad hoc patents, with the terms and durations decided on a case-by-case basis as before). Under the 1474 law, Venice was soon granting patent monopolies to the introducers of various mills, pumps, dredges, textile machines, printing techniques, and even special kinds of lasagna. It granted over a hundred patents in the first half of the sixteenth century, with many more thereafter.

From Venice, the use of patent monopolies as an instrument of policy spread abroad, with the initiative coming from the would-be introducers of novelties themselves. In the mid-fifteenth century, for example, a French inventor who had acquired patents in Venice was also successfully lobbying for similar privileges from the archbishop of Salzburg, the duke of Ferrara, and the Hapsburg Holy Roman Emperor. The use of patent monopolies thus soon diffused to the rest of Italy, to Germany, and to the various dominions of the Spanish emperor — including Spain itself, its American colonies, and the Low Countries.

And, eventually, to England. But not in the way we might expect. In 1496, the Venetian explorer Zuan Chabotto (aka John Cabot) acquired a patent monopoly from Henry VII over the trade and products of any lands he was to discover — a legal procedure unlike anything that earlier English explorers had attempted (they had merely been granted licenses). Cabot’s grant even differed from the agreements made by Christopher Columbus with the Spanish crown, or by earlier explorers for the Portuguese. Columbus, for example, was effectively granted a patent of nobility — the hereditary titles of viceroy, admiral, and governor. He and the Portuguese explorers were direct agents of the crown, with military and justice-dispensing responsibilities over any newly conquered lands — a model derived from the Christian conquests of Muslim Iberia. Columbus effectively became a marcher lord, a custodian and defender of Spain’s new borderlands.

August 2, 2020

QotD: Marx’s imperfect economic understanding

We’re at the 200th anniversary of Karl Marx’s birth – also the 201st of Ricardo’s publication, the 242nd of Smith’s Wealth of Nations. And it has to be said that the latter two were more perceptive analysts of the human condition and also contributed vastly more to human knowledge and happiness. Most of the bits that Marx got right in economics were in fact lifted from those other two. The one big thing he got wrong was not to believe them about markets.

We can find, if we look properly, Marx’s insistences of how appalling monopoly capitalism would be in Smith. They’re both right too, it would be appalling. But we do have to understand what they both mean by this. In modern terms they mean monopsony, more specifically the monopoly buyer of labour. What is it that prevents this? Competition in the market among capitalists for access to the labour they desire to exploit. That very competition decreasing the amount of grinding of faces into the dust they’re able to do. Henry Ford’s $5 a day is an excellent example of this very point.

Ford wanted access to the best manufacturing labour of his time. He also wanted to have a lower turnover of that labour, lower training costs. So, he doubled wages (actually, normal wages plus a 100% bonus if you did things the Ford Way) and got that labour. At which point all the other manufacturers had to try and compete with those higher wages in order to get that labour they wanted to expropriate the sweat of the brow from. Marx did get this, he pointed out that exactly this sort of competition, in the absence of a reserve army of the unemployed, is what would raise real wages as productivity improved.

Smith also didn’t like the setting of wages as it precluded just such competition and such wage rises.

Where Marx went wrong was in not realising this power of markets. He knew of them, obviously, understood the idea, but just didn’t understand their power to ameliorate, destroy even, that march to monopoly capitalism.

[…]

The thing we really need to know on this bicentenary about Karl Marx is that he was wrong. He just never did grasp the power of markets to disrupt, even prevent, the tendencies he saw in capitalism. Specifically, and something we all need to know today, the power of competition among capitalists as the method of improving the lives of all us wage slaves. You know, that’s why we proletariat today, exploited as we are and ground into the dust, are the best fed, longest lived and richest, in every sense of the word, human beings who have ever existed. Something which is, if we’re honest about it, not a bad recommendation for a socio-economic system really. You know, actually working? Achieving the aim of improving the human condition?

Tim Worstall, “Marx At 200 – Yes, He Was Wrong, Badly Wrong”, Continental Telegraph, 2018-05-04.

July 15, 2020

When The Dutch Ruled The World: Rise and Fall of the Dutch East India Company

Business Casual

Published 14 Sep 2018Thanks to Cheddar for sponsoring this episode! Check out their video on the iconic ad campaign that saved Old Spice here: https://chdr.tv/youtu8b4a6

⭑ Subscribe to Business Casual → http://gobc.tv/sub

⭑ Enjoyed the vid? Hit the like button!Follow us on:

► Twitter → http://gobc.tv/twtr

► Instagram → https://gobc.tv/ig

► LinkedIn → https://gobc.tv/linkedin

► Reddit → https://gobc.tv/reddit

► Medium → https://gobc.tv/medium

April 24, 2020

Prizes, patents, and the Society of the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce

In the most recent Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes explains why the Society of the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce (now the Royal Society of Arts) wasn’t a fan of the British patent system and preferred to award prizes in areas that were unlikely to generate monopoly situations:

The back of the Royal Society of Arts building in London, 25 August 2005.

Photo by C.G.P. Grey (www.CGPGrey.com) via Wikimedia Commons.

… the Society’s early members had an aversion to monopolies, and patents are, after all, temporary monopolies. But there was actually a more practical reason to not give rewards to patented inventions. In fact, quite a few active members of the Society were themselves patentees, and patents for inventions were not generally lumped together for condemnation with practices like forestalling and engrossing. The practical reason for banning patents was that there was no point giving a prize for something that people were already doing anyway. Patents were expensive in the eighteenth century — depending on how you account for inflation, it could cost about £300,000 in modern terms to obtain one — so the fact that there was a patent for a process was a clear indication that it might be profitable. The Society, by contrast, was supposed to encourage things that would not otherwise have been done.

Thus, when a patent had already been granted for a process the Society had been considering giving a premium for, it purposefully backed down — not because the prize would infringe on the patent, but because its encouragement was no longer necessary. And so the effect of the ban on patented inventions was that the Society received, even unsolicited, exactly the kinds of inventions that there was less monetary incentive to invent. Occasionally, this meant trivial improvements — minor tweaks, here and there, to existing processes. An engineer might patent one invention, but not see it worth their time patenting another — through the Society’s prizes, they might at least get a bit of cash for it, or some recognition. The improvement would also be promoted through the Society’s publications. Or, the Society received inventions that were far from trivial, like the scandiscope for cleaning chimneys [here], but which were not all that profitable: inventions that saved lives, or had other beneficial effects on the health and wellbeing of workers and consumers. And finally, the Society received innovations that could not be patented, such as agricultural practices and the opening of new import trades. In the early nineteenth century the Society awarded its prizes to a whole host of naval officers, including an admiral, who came up with flag-based signalling systems between ships — early forms of semaphore.

Another effect of the ban on patents was that the Society also attracted submissions from different demographics. Many of its submissions came from people who were too poor to afford patents, as well as from those who were too rich — wealthy aristocrats for whom commercial considerations might seem vulgar. The poor would generally go for the cash prizes, and the aristocrats for the honorary medals. And the prizes were used by people who might otherwise be socially excluded from invention. In 1758, for example, the Society instructed its members in the American colonies to accept submissions from Native Americans. It also allowed women to claim premiums (just as it allowed them to be members). My favourite example is Ann Williams, postmistress at Gravesend, in Kent, who won twenty guineas from the Society in 1778 for her observations on the feeding and rearing of silk-worms. She kept them in one of the post-office pigeon-holes, referring to them affectionately as “my little family” of “innocent reptiles”. Unlike other elements of society, the Society of Arts accepted, as she put it to them, that “curiosity is inherent to all the daughters of Eve.”

The Society thus encouraged the kinds of inventions that might not otherwise have been created, and catered to the kinds of inventors who might not otherwise have been recognised. Rather than competing with the patent system, it complemented it, filling in the gaps that it left. The Society operated at the margins, and only at the margins, to the better completion of the whole. It found its niche, to the benefit of innovation overall.

March 3, 2020

QotD: Public service and competitive private enterprise

Anyone who deals with the general UK public (coercive) sector regularly, knows it is a cesspit of laziness, incompetence, arrogance and corruption, riddled with civil servants that are neither civil nor servants.

And I’m not suggesting that the levels of corruption and incompetence are comparable to those found in third world hellholes. A local official in your county council is very unlikely to demand a bribe and then have your daughter raped by his buddies if you decline. He’s especially unlikely to get away with it, and then douse your family in petrol and burn them alive if you complain – those are the levels of corruption found elsewhere in the world, so we need to retain some perspective here.

But those countries have not benefited from a thousand years of sacrifice to earn us a culture that has learned through bitter experience how to run a country. Our civil servants should be performing at the highest standard and be the best in the world, because what they inherited was a culture that conquered that world, and brought civilisation and progress (often at great cost) to every corner of it.

That they have fallen from these heights and now occupy such low places should be a matter for great national shame. And yet they continue to lord it over those they pretend to serve – try calling your local planning department if you want instruction in how supercilious a local functionary feels able to be when speaking to those he claims to serve. If you just want them to do their job, you better be prepared to beg.

Whereas on the flip side, we might agree that the private (voluntary) sector is largely filled with honest and hardworking people and entrepreneurs, but there are crony capitalists out there too.

Your local butcher and baker (those that have survived the regulatory avalanches under which the crony capitalists have begged their pet politicians to bury them) remain staunch servants of their customers (through regard to their own interests), whereas oligoplists (supermarkets, telcos, insurance companies, banks, energy suppliers or transport companies) deliver to us just what the monopolists of government do – an icy contempt that would soon turn to withering small arms fire if the laws allowed it.

Alex Noble, “Corruption In The Coercive And Voluntary Sectors: Rotten Apples? Or The Tips of Icebergs?”, Continental Telegraph, 2019-12-02.

March 2, 2020

Downfall of the Superpower China – Ming and Qing Dynasty l HISTORY OF CHINA

IT’S HISTORY

Published 17 Aug 2015With the dynasties of the Ming and the Qing came social security and flourishing international trade. The White Lotus Movement advocated progressive thinking in the time of the conservative Ming dynasty. In 1616 the Qing dynasty came to power. Also known as the Manchu dynasty, the Qing refused to open their borders to limitless trade which led to frustrated European merchants. This caused hostility and mistrust of the “barbaric Chinese”. Shortly thereafter China’s economy lost its race against European Colonialism and would lose military influence after gunpowder reached Europe. All about the fall of the former Chinese superpower in this episode on IT’S HISTORY!

» SOURCES

Videos: British Pathé (https://www.youtube.com/user/britishp…)

Pictures: mainly Picture Alliance

Content:

Twitchett, Denis and Loewe, Michael. The Cambridge History of China. Cambridge University Press.

Wilkinson, Endymion, Chinese History: A New Manual. Harvard University, Asia Center

Loewe, Michael; Shaughnessy, Edward L. The Cambridge History of Ancient China. Cambridge University Press

John M. Roberts A Short History of the World. Oxford University Press

Xu, Pingfang The Formation of Chinese Civilization: An Archaeological Perspective. Yale University Press.

Fairbank, J. K.; Goldman, M. China: A New History. Harvard University Press. ”» ABOUT US

IT’S HISTORY is a ride through history – Join us discovering the world’s most important eras in IN TIME, BIOGRAPHIES of the GREATEST MINDS and the most important INVENTIONS.» HOW CAN I SUPPORT YOUR CHANNEL?

You can support us by sharing our videos with your friends and spreading the word about our work.» CAN I EMBED YOUR VIDEOS ON MY WEBSITE?

Of course, you can embed our videos on your website. We are happy if you show our channel to your friends, fellow students, classmates, professors, teachers or neighbors. Or just share our videos on Facebook, Twitter, Reddit etc. Subscribe to our channel and like our videos with a thumbs up.» CAN I SHOW YOUR VIDEOS IN CLASS?

Of course! Tell your teachers or professors about our channel and our videos. We’re happy if we can contribute with our videos.» CREDITS

Presented by: Guy Kiddey

Script by: Guy Kiddey

Directed by: Daniel Czepelczauer

Director of Photography: Markus Kretzschmar

Music: Markus Kretzschmar

Sound Design: Bojan Novic

Editing: Markus KretzschmarA Mediakraft Networks original channel

Based on a concept by Florian Wittig and Daniel Czepelczauer

Executive Producers: Astrid Deinhard-Olsson, Spartacus Olsson

Head of Production: Michael Wendt

Producer: Daniel Czepelczauer

Social Media Manager: Laura Pagan and Florian WittigContains material licensed from British Pathé

All rights reserved – © Mediakraft Networks GmbH, 2015

February 29, 2020

The metallic nickname of Henry VIII

In the most recent Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes outlines the rocky investment history for German mining firms in England during the Tudor period:

Cropped image of a Hans Holbein the Younger portrait of King Henry VIII at Petworth House.

Photo by Hans Bernhard via Wikimedia Commons.

It’s an especially interesting case of England’s technological backwardness, given that copper was a material of major strategic importance: a necessary ingredient for the casting of bronze cannon. And it was useful for other industries, especially when mixed with zinc to form brass. Brass was the material of choice for accurate navigational instruments, as well as for ordinary pots and kettles. Most importantly, brass wire was needed for wool cards, used to straighten the fibres ready for spinning into thread. A cheaper and more secure supply of copper might thus potentially make England’s principal export, woollen cloth, even more competitive — if only the English could also work out how to produce brass.

The opportunity to introduce a copper industry appeared in 1560, when German bankers became involved in restoring the gold and silver content of England’s currency. The expensive wars of Henry VIII and Edward VI in the 1540s had prompted debasements of the coinage, to the short-term benefit of the crown, but to the long-term cost of both crown and country. By the end of Henry VIII’s reign, the ostensibly silver coins were actually mostly made of copper (as the coins were used, Henry’s nose on the faces of the coins wore down, revealing the base metal underneath and earning him the nickname Old Coppernose). The debased money continued to circulate for over a decade, driving the good money out of circulation. People preferred to hoard the higher-value currency, to send it abroad to pay for imports, or even to melt it down for the bullion. The weakness of the pound was an especial problem for Thomas Gresham, Queen Elizabeth’s financier, in that government loans from bankers in London and Antwerp had to be repaid in currency that was assessed for its gold and silver content, rather than its face value. Ever short of cash, the government was constantly resorting to such loans, made more expensive by the lack of bullion.

Restoring the currency — calling in the debased coins, melting them down, and then re-minting them at a higher fineness — required expertise that the English did not have. From France, the mint hired Eloy Mestrelle to strike the new coins by machine rather than by hand. (He was likely available because the French authorities suspected him of counterfeiting — the first mention of him in English records is a pardon for forgery, a habit that apparently died hard as he was eventually hanged for the offence). And to do the refining, Gresham hired German metallurgists: Johannes Loner and Daniel Ulstätt got the job, taking payment in the form of the copper they extracted from the debased coinage (along with a little of the silver). It turned out to be a dangerous assignment: some of the copper may have been mixed with arsenic, which was released in fumes during the refining process, thus poisoning the workers. They were prescribed milk, to be drunk from human skulls, for which the government even gave permission to use the traitors’ heads that were displayed on spikes on London Bridge — but to little avail, unfortunately, as some of them still died.

Loner and Ulstätt’s payment in copper appears to be no accident. They were agents of the Augsburg banking firm of Haug, Langnauer and Company, who controlled the major copper mines in Tirol. Having obtained the English government as a client, they now proposed the creation of English copper mines. They saw a chance to use England as a source of cheap copper, with which they could supply the German brass industry. It turns out that the tale of the multinational firm seeking to take advantage of a developing country for its raw materials is an extremely old one: in the 1560s, the developing country was England.

Yet the investment did not quite go according to plan. Although the Germans possessed all of the metallurgical expertise, the English insisted that the endeavour be organised on their own terms: the Company of Mines Royal. Only a third of the company’s twenty-four shares were to be held by the Germans, with the rest purchased by England’s political and mercantile elite: people like William Cecil (the Secretary of State) and the Earl of Leicester, Robert Dudley (the Queen’s crush). It was an attractive investment, protected from competition by a patent monopoly for mines of gold, silver, copper, and mercury in many of the relevant counties, as well as a life-time exemption for the investors from all taxes raised by parliament (in those days, parliament was pretty much only assembled to legitimise the raising of new taxes).