In the latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes traces the lines of descent from the Letters patent of the Middle Ages, through Venetian legal innovations, to what began to resemble our modern patent system:

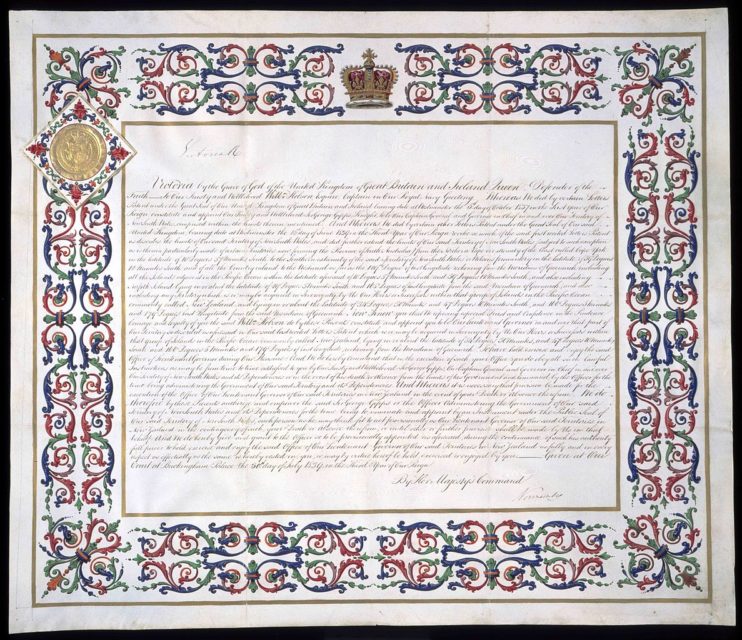

Letters Patent Issued by Queen Victoria, 1839

On 15 June 1839 Captain William Hobson was officially appointed by Queen Victoria to be Lieutenant Governor General of New Zealand. Hobson (1792 – 1842) was thus the first Governor of New Zealand. This position was renamed in 1907 as “Governor General”. Hobson arrived in New Zealand in late January 1840, and oversaw the signing of te Tiriti o Waitangi only a few days later. By the end of 1840, New Zealand became a colony in its own right and Hobson moved the capital of the colony from the Bay of Islands to Auckland. He served as Governor until his death in 1842 after he suffered a stroke at the age of 49.

Constitutional Records group of Archives NZ via Wikimedia Commons.

Patents for invention — temporary monopolies on the use of new technologies — are frequently cited as a key contributor to the British Industrial Revolution. But where did they come from? We typically talk about them as formal institutions, imposed from above by supposedly wise rulers. But their origins, or at least their introduction to England, tell a very different story.

England’s monarchs had long used their prerogative powers to grant special dispensations by letters patent — that is, orders from the monarch that were open for all the public to see (think of the word patently, from the same root, which means openly or clearly). For the most part, such public proclamations had been used to grant titles of nobility, or to appoint people to positions in various official hierarchies — legal, religious, and governmental. And, of course, letters patent could be used to promote the introduction of new technologies.

[…]

Monopolies in general, of course, over particular trades or industries had been granted for centuries, by rulers all across Europe. They granted such privileges to groups of merchants, artisans, and city-dwellers, giving them rights to organise and regulate their own activities as guilds or as city corporations. Inherent to all such charters was the ability of the in-group to restrict competition from outsiders, at least within the confines of their city. And the ruler, in exchange for granting such privileges, typically received a share of the guild’s or corporation’s revenues. But such monopolies were very rarely given to individuals. When they were, it was often so unpopular as to be almost immediately overturned. And they were rarely used to encourage innovation.

With one exception: Italy. Throughout the fifteenth century, some Italian city guilds had begun to forbid their members from copying newly-invented patterns for silk and woollen cloth, effectively granting a monopoly over those patterns to the individual inventors. In Venice, a 50-year monopoly was granted in 1416 to one Franciscus Petri, of Rhodes, to introduce superior fulling mills. In Florence, the famous architect and engineer Filippo Brunelleschi was granted a monopoly in 1421 for a vessel he designed for transporting heavy loads of marble, in exchange for revealing the secrets of his design. The printing press was also introduced to Venice using such a privilege, with a 5-year monopoly granted in 1469 to Johannes of Speyer, though he died only a few months after receiving it. And these ad hoc grants were made with increasing frequency, such that in 1474 Venice legislated to make them more systematic, declaring that 10-year monopolies could be obtained for all new technologies, either invented or imported (though it continued to also grant ad hoc patents, with the terms and durations decided on a case-by-case basis as before). Under the 1474 law, Venice was soon granting patent monopolies to the introducers of various mills, pumps, dredges, textile machines, printing techniques, and even special kinds of lasagna. It granted over a hundred patents in the first half of the sixteenth century, with many more thereafter.

From Venice, the use of patent monopolies as an instrument of policy spread abroad, with the initiative coming from the would-be introducers of novelties themselves. In the mid-fifteenth century, for example, a French inventor who had acquired patents in Venice was also successfully lobbying for similar privileges from the archbishop of Salzburg, the duke of Ferrara, and the Hapsburg Holy Roman Emperor. The use of patent monopolies thus soon diffused to the rest of Italy, to Germany, and to the various dominions of the Spanish emperor — including Spain itself, its American colonies, and the Low Countries.

And, eventually, to England. But not in the way we might expect. In 1496, the Venetian explorer Zuan Chabotto (aka John Cabot) acquired a patent monopoly from Henry VII over the trade and products of any lands he was to discover — a legal procedure unlike anything that earlier English explorers had attempted (they had merely been granted licenses). Cabot’s grant even differed from the agreements made by Christopher Columbus with the Spanish crown, or by earlier explorers for the Portuguese. Columbus, for example, was effectively granted a patent of nobility — the hereditary titles of viceroy, admiral, and governor. He and the Portuguese explorers were direct agents of the crown, with military and justice-dispensing responsibilities over any newly conquered lands — a model derived from the Christian conquests of Muslim Iberia. Columbus effectively became a marcher lord, a custodian and defender of Spain’s new borderlands.