Consider the Reformation. I’m in no way qualified to walk you through all the various doctrinal issues, but in this case a superficial analysis is not only sufficient, it’s actually better. Instead of getting lost in the theological weeds, I want to focus on the process. So let’s stipulate for the sake of argument that nothing Luther said was all that original, theologically — you can find pretty much any tenet of “Lutherism” (as it then was) somewhere in the past, often among the Church Fathers (the “double predestination” that drove Calvinists insane is straight out of St. Augustine, for example). Wyclif, Hus, Nicholas of Cusa, Marsilius of Padua, all those guys were proto-Luthers, at least in part.

The thing about Luther, then, wasn’t what he said, so much as how he said it.

Martin Luther was the world’s first spin doctor. Though he insisted for a long time that his famous 95 Theses were, and were always intended to be, a scholastic debate between clergymen, Luther mastered the use of printed propaganda. His opponents soon followed, or tried to, in an ever-increasing spiral of printed viciousness. Mutatis mutandis, the exchanges between Luther, Erasmus, Thomas More (to say nothing of a thousand lesser lights) and their opponents all sound shockingly Current Year. They’re snarky and waspish at best, grotesque ad hominem at worst. Modern flame wars have nothing on the way Thomas More and William Tyndale tore into each other, for instance, and More and Tyndale were rank amateurs compared to Luther.

As with the Current Year, where being first on social media is the only criterion that matters, so the printing press injected something very like “hot takes” into the late-Medieval intellectual atmosphere. If you tried to respond to your opponents the old-fashioned way — with closely reasoned, heavily cited arguments, on parchment, hand-copied by monks — you might win the intellectual battle … 500 years later, among historians who thank you for providing such a useful glimpse into late-Medieval mentalités, but in your own time you’d get fired at best, get burned at the stake at worst, if you didn’t respond instantly, in kind.

The printing press, in other words, represented a quantum leap in the velocity of information. Those who grasped its fundamentals prospered, while those who fell behind perished. King Henry VIII, for instance, fatally damaged his cherished intellectual reputation when he deigned to attack to Luther in person. Luther hit back with a tirade that wouldn’t be out of place on Twitter1, and Henry responded in kind, and now the king, who was hip-deep in self-inflicted shit by that point, had to drop the fight. Having been publicly abused by a mere ex-monk, he had to quit the field with his tail between his legs.

Severian, “Velocity of Information”, Rotten Chestnuts, 2021-08-10.

1. Again, mutatis mutandis. Though this sounds to modern ears like an abject apology on Luther’s part (“especially as I am the offscouring of the world, a mere worm who ought only to live in contemptuous neglect”, etc.), in context it’s a vicious attack. For one thing, what’s a great king like Henry doing responding to a “mere worm”? And Henry had to know, since Wolsey did nothing without his master’s orders … except everyone had heard the rumors that Henry was just a dimwitted playboy, and Cardinal Wolsey was really the king in all but name, so maybe he didn’t know. Either way Henry, who prided himself on being an intellectual, was a fool. That’s the kind of thing that would get you executed in the 16th century, and here’s this “mere worm” publishing it, for all the world to see, with no possibility of reprisal from a supposedly puissant monarch.

August 20, 2024

August 17, 2024

QotD: Sheep and wool in the ancient and medieval world

Our second fiber, wool, as readers may already be aware, comes from sheep (although goat and horse-hair were used rarely for some applications; we’re going to stick to sheep’s wool here). The coat of a sheep (its fleece) has three kinds of fibers in it: wool, kemp and medullated fibers. Kemp fibers are fairly weak and brittle and won’t accept dye and so are generally undesirable, although some amount of kemp may end up in wool yarn. Likewise, medullated fibers are essentially hair (rather than wool) and lack elasticity. But the wool itself, composed mostly of the protein keratin along with some lipids, is crimped (meaning the fibers are not straight but very bendy, which is very valuable for making fine yarns) and it is also elastic. There are reasons for certain applications to want to leave some of the kemp in a wool yarn that we’ll get to later, but for the most part it is the actual wool fibers that are desirable.

Sheep themselves probably descend from the wild mouflon (Ovis orientalis) native to a belt of uplands bending over the northern edge of the fertile crescent from eastern Turkey through Armenia and Azerbaijan to Iran. The fleeces of these early sheep would have been mostly hair and kemp rather than wool, but by the 4th millennium BC (as early as c. 3700 BC), we see substantial evidence that selective breeding for more wool and thicker coats has begun to produce sheep as we know them. Domestication of course will have taken place quite a bit earlier (selective breeding is slow to produce such changes), perhaps around 10,000 BC in Mesopotamia, spreading to the Indus river valley by 7,000 BC and to southern France by 6,000 BC, while the replacement of many hair breeds of sheep with woolly sheep selectively bred for wool production in Northern Mesopotamia dates to the third century BC.1 That process of selective breeding has produced a wide variety of local breeds of sheep, which can vary based on the sort of wool they produce, but also fitness for local topography and conditions.

As we’ve already seen in our discussion on Steppe logistics, sheep are incredibly useful animals to raise as a herd of sheep can produce meat, milk, wool, hides and (in places where trees are scarce) dung for fuel. They also only require grass to survive and reproduce quickly; sheep gestate for just five months and then reach sexual maturity in just six months, allowing herds of sheep to reproduce to fill a pasture quickly, which is important especially if the intent is not merely to raise the sheep for wool but also for meat and hides. Since we’ve already been over the role that sheep fill in a nomadic, Eurasian context, I am instead going to focus on how sheep are raised in the agrarian context.

While it is possible to raise sheep via ranching (that is, by keeping them on a very large farm with enough pastureland to support them in that one expansive location) and indeed sheep are raised this way today (mostly in the Americas), this isn’t the dominant model for raising sheep in the pre-modern world or even in the modern world. Pre-modern societies generally operated under conditions where good farmland was scarce, so flat expanses of fertile land were likely to already be in use for traditional agriculture and thus unavailable for expansive ranching (though there does seem to be some exception to this in Britain in the late 1300s after the Black Death; the sudden increase in the cost of labor – due to so many of the laborers dying – seems to have incentivized turning farmland over to pasture since raising sheep was more labor efficient even if it was less land efficient and there was suddenly a shortage of labor and a surplus of land). Instead, for reasons we’ve already discussed, pastoralism tends to get pushed out of the best farmland and the areas nearest to towns by more intensive uses of the land like agriculture and horticulture, leaving most of the raising and herding of sheep to be done in the rougher more marginal lands, often in upland regions too rugged for farming but with enough grass to grow. The most common subsistence strategy for using this land is called transhumance.

Transhumant pastoralists are not “true” nomads; they maintain permanent dwellings. However, as the seasons change, the transhumant pastoralists will herd their flocks seasonally between different fixed pastures (typically a summer pasture and a winter pasture). Transhumance can be either vertical (going up or down hills or mountains) or horizontal (pastures at the same altitude are shifted between, to avoid exhausting the grass and sometimes to bring the herds closer to key markets at the appropriate time). In the settled, agrarian zone, vertical transhumance seems to be the most common by far, so that’s what we’re going to focus on, though much of what we’re going to talk about here is also applicable to systems of horizontal transhumance. This strategy could be practiced both over relatively short distances (often with relatively smaller flocks) and over large areas with significant transits (see the maps in this section; often very significant transits) between pastures; my impression is that the latter tends to also involve larger flocks and more workers in the operation. It generally seems to be the case that wool production tended towards the larger scale transhumance. The great advantage of this system is that it allows for disparate marginal (for agriculture) lands to be productively used to raise livestock.

This pattern of transhumant pastoralism has been dominant for a long time – long enough to leave permanent imprints on language. For instance, the Alps got that name from the Old High German alpa, alba meaning which indicated a mountain pasturage. And I should note that the success of this model of pastoralism is clearly conveyed by its durability; transhumant pastoralism is still practiced all over the world today, often in much the same way as it was centuries or millennia ago, with a dash of modern technology to make it a bit easier. That thought may seem strange to many Americans (for whom transhumance tends to seem very odd) but probably much less strange to readers almost anywhere else (including Europe) who may well have observed the continuing cycles of transhumant pastoralism (now often accomplished by moving the flocks by rail or truck rather than on the hoof) in their own countries.

For these pastoralists, home is a permanent dwelling, typically in a village in the valley or low-land area at the foot of the higher ground. That low-land will generally be where the winter pastures are. During the summer season, some of the shepherds – it does not generally require all of them as herds can be moved and watched with relatively few people – will drive the flocks of sheep up to the higher pastures, while the bulk of the population remains in the village below. This process of moving the sheep (or any livestock) over fairly long distances is called droving and such livestock is said to be moved “on the hoof” (assuming it isn’t, as in the modern world, transported by truck or rail). Sheep are fairly docile animals which herd together naturally and so a skilled drover can keep large flock of sheep together on their own, sometimes with the assistance of dogs bred and trained for the purpose, but just as frequently not. While cattle droving, especially in the United States, is often done from horseback, sheep and goats are generally moved with the drovers on foot.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Clothing, How Did They Make It? Part I: High Fiber”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2021-03-05.

1. On this, note E. Vila and D. Helmer, “The Expansion of Sheep Herding and the Development of Wool Production in the Ancient Near East” in Wool Economy in the Ancient Near East and the Aegean, eds. C. Breniquet and C. Michel (2014), which has the archaeozoological data).

August 12, 2024

Robin Hood, But Make it ⚔️ICONIC⚔️

Jill Bearup

Published Apr 29, 2024The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938) is a classic, and I am hopefully unlikely to get in copyright trouble if I use huge chunks of it. So prepare for an exhaustive (or possibly exhausting) fight breakdown, and a few minor comments about Errol Flynn and parrying.

(more…)

August 3, 2024

The Battle of Lepanto, 7 October 1571

Big Serge looks at the decisive battle between the “Holy League” (Spain, Venice, Genoa, Savoy, Tuscany, the Papal States and the Order of St. John) against the Ottoman navy in the Ionian Sea in 1571:

“The Battle of Lepanto”

Oil painting by Juan Luna, 1887. From the Senate of Spain collection via Wikimedia Commons.

Lepanto is a very famous battle, and one which means different things to different people. To a devout Roman Catholic like Chesterton, Lepanto takes on the romanticized and chivalrous form of a crusade — a war by the Holy League against the marauding Turk. At the time it was fought, to be sure, this was the way many in the Christian faction thought of their fight. Chesterton, for his part, writes that “the Pope has cast his arms abroad for agony and loss, and called the kings of Christendom for swords about the Cross”.

For historians, Lepanto is something like a requiem for the Mediterranean. Placed firmly in the early-modern period, fought between the Catholic powers of the inland sea and the Ottomans, then on the crest of their imperial rise, Lepanto marked a climactic ending to the long period of human history where the Mediterranean was the pivot of the western world. The coasts of Italy, Greece, the Levant, and Egypt — which for millennia had been the aquatic stomping grounds of empire — were treated to one more great battle before the Mediterranean world was permanently eclipsed by the rise of the Atlantic powers like the French and English. For those particular devotees of military history, Lepanto is very famous indeed as the last major European battle in which galleys — warships powered primarily by rowers — played the pivotal role.

There is some truth in all of this. The warring navies at Lepanto fought a sort of battle that the Mediterranean had seen many times before — battle lines of rowed warships clashing at close quarters in close proximity to the coast. A Roman, Greek, or Persian admiral may not have understood the swivel guns, arquebusiers, or religious symbols of the fleets, but from a distance they would have found the long lines of vessels frothing the waters with their oars to be intimately familiar. This was the last time that such a grand scene would unfold on the blue waters of the inner sea; afterwards the waters would more and more belong to sailing ships with broadside cannon.

Lepanto was all of these things: a symbolic religious clash, a final reprise of archaic galley combat, and the denouement of the ancient Mediterranean world. Rarely, however, is it fully understood or appreciated in its most innate terms, which is to say as a military engagement which was well planned and well fought by both sides. When Lepanto is discussed for its military qualities, stripped of its religious and historiographic significance, it is often dismissed as a bloody, unimaginative, and primitive affair — a mindless slugfest (the stereotypical “land battle at sea”) using an archaic sort of ship which had been relegated to obsolescence by the rise of sail and cannon.

Here we wish to give Lepanto, and the men who fought it, their proper due. The continued use of galleys well into the 16th century did not reflect some sort of primitiveness among the Mediterranean powers, but was instead an intelligent and sensible response to the particular conditions of war on that sea. While galleys would, of course, be abandoned eventually in favor of sailing ships, at Lepanto they remained potent weapons systems which fit the needs of the combatants. Far from being a mindless orgy of violence, Lepanto was a battle characterized by intelligent battle plans in which both the Turkish and Christian command sought to maximize their own advantages, and it was a close run and well fought affair. Lepanto was indeed a swan song for a very old form of Mediterranean naval combat, but it was a well conceived and well fought one, and Turkish and Christian fleets alike did justice to this venerable and ancient form of battle.

July 9, 2024

What it was like to visit a Medieval Tavern

Tasting History with Max Miller

Published 27 Mar 2024Medieval stew with meat, spices, and verjuice, and thickened with egg yolks

City/Region: England

Time Period: 15th CenturySome medieval taverns may have had what is called a perpetual stew bubbling away. The idea is basically what it sounds like: as stew was taken out, more ingredients would be added in so that the stew kept on stewing. In southern France, there was a perpetual stew that was served from the 15th century (around when this recipe was written) all the way up until WWII, when they couldn’t get the right ingredients.

I have opted to not make this stew perpetual, but it is delicious. The medieval flavor of super tender meat with spices and saffron is so interesting, especially with the added acidity and sweetness from the verjuice.

A note on thickening with egg yolks: if you need to reheat your stew after adding the egg yolks, like I did, they may scramble a bit. The stew is still delicious, it’s just the texture that changes a little and it won’t be quite as thick.

Vele, Kede, or Henne in bokenade

Take Vele, Kyde, or Henne, an boyle hem in fayre Water, or ellys in freysshe brothe, and smyte hem in pecys, and pyke hem clene; an than draw the same brothe thorwe a straynoure, an caste there-to Percely, Swag, Ysope, Maces, Clowys, an let boyle tyl the flesshe be y-now; than sette it from the fyre, and alye it up with raw yolkys of eyroun, and caste ther-to pouder Gyngere, Veriows, Safroun, and Salt, and thanne serve it forth for a gode mete.

— Harleian Manuscript 279, 15th Century

June 30, 2024

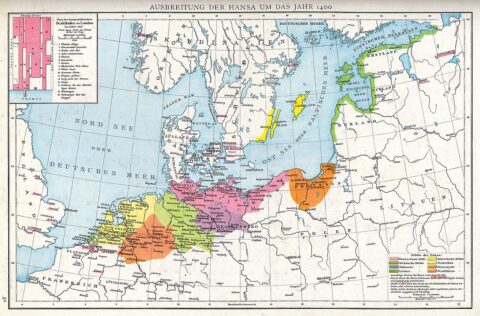

The medieval salt trade in the Baltic

In the long-awaited third part of his series on salt, Anton Howes discusses how the extremely low salt level of water in the Baltic Sea helped create a vast salt trade dominated by the merchant cities of the Hanseatic League:

The extent of the Hanseatic League in 1400.

Plate 28 of Professor G. Droysen’s Allgemeiner Historischer Handatlas, published by R. Andrée, 1886, via Wikimedia Commons.

It’s difficult to appreciate salt’s historical significance because it’s now so abundant. Societies used to worry about salt supplies — for preparing and preserving food — as a matter of basic survival. Now we use the vast majority of it for making chemicals or chucking on our roads to keep them from getting icy, while many salt-making plants don’t even operate at full capacity. Yet the story of how we came to achieve salt superabundance is a long and complicated one.

In Part I of this series we looked at salt as a kind of general-purpose technology for the improvement of food, as well as a major revenue-raiser for empires — especially when salt-producing coastal areas could dominate salt-less places inland. In Part II we then looked at a couple of places that were all the more interesting for being both coastal and remarkably salt-less: the coast of Bengal and the Baltic Sea. One was to be exploited by the English East India Company, which needlessly propped up a Bengalese salt industry at great human cost. The other, however, was to prove a more contested prize — and ultimately the place that catalysed the emergence of salt superabundance.

It’s worth a brief recap of where we left the Baltic. Whereas the ocean is on average 3.5% salt, along the Baltic coast it’s at just 0.3% or lower, which would require about twelve times as much time and fuel to produce a given quantity of salt. Although there are a few salt springs near the coast, they were nowhere near large enough to supply the whole region. So from the thirteenth century the Baltic’s salt largely came from the inland salt springs at Lüneburg, supplied via the cities of Lübeck and Hamburg downstream. These two cities had a common interest against the kingdom of Denmark, which controlled the straits between the North and Baltic seas, and created a coalition of trading cities that came to be known as the Hanseatic League. The League resoundingly defeated the Danes in the 1360s and 1430s so that their trade in salt — and the fish they preserved with it — could remain free.

But Lüneburg salt — and by extension the League itself — was soon to face competition.

Lüneburg could simply not keep up with the growth of Baltic demand, as the region’s population became larger and wealthier. And so more and more salt had to come from farther afield, from the Bay of Biscay off France’s western coast, as well as from Setúbal in Portugal and from southern Spain.1 This “bay salt” — originally referring to just the Bay of Bourgneuf, but then extended to the entire Bay of Biscay, and often to all Atlantic solar-evaporated salt — was made by the sun and the wind slowly evaporated the seawater from a series of shallow coastal pools, with the salt forming in coarse, large-grained pieces that were skimmed off the top. Bay salt, however, inevitably ended up mixed with some of the sand and dirt from the bottoms of the pools in which it was held, while the seawater was never filtered, meaning that the salt was often brown, green, grey or black depending on the skill of the person doing the skimming — only the most skilled could create a bay salt that was white. And it often still contained lots of other chemicals found in seawater, like magnesium chloride and sulphate, calcium carbonate and sulphate, potassium chloride and so on, known as bitterns.2

Bay or “black” salt, made with the heat of the sun, was thus of a lower quality than the white salt boiled and refined from inland salt springs or mined as rock. Its dirt discoloured and adulterated food. Its large grains meant it dissolved slowly and unevenly, slowing the rate at which it started to penetrate and preserve the meat and fish — an especially big problem in warmer climates where flesh spoiled quickly. And its bitterns gave it a bitter, gall taste, affecting the texture of the flesh too. Bay salt, thanks to the bitterns, would “draw forth oil and moisture, leading to dryness and hardness”, as well as consuming “the goodness or nutrimental part of the meat, as moisture, gravy, etc.”3 The resulting meat or fish was often left shrunken and tough, while bitterns also slowed the rate at which salt penetrated them too. Bay-salted meat or fish could often end up rotten inside.

But for all these downsides, bay salt required little labour and no fuel. Its main advantage was that it was extremely cheap — as little as half the price of white Lüneburg salt in the Baltic, despite having to be brought from so much farther away.4 Its taste and colour made it unsuitable for use in butter, cheese, or on the table, which was largely reserved for the more expensive white salts. But bay salt’s downsides in terms of preserving meat and fish could be partially offset by simply applying it in excessive quantities — every three barrels of herring, for example, required about a barrel of bay salt to be properly preserved.5

By 1400, Hanseatic merchants were importing bay salt to the Baltic in large and growing quantities, quickly outgrowing the traditional supplies. No other commodity was as necessary or popular: over 70% of the ships arriving to Reval (modern-day Tallinn in Estonia) in the late fifteenth century carried salt, most of it from France. But Hanseatic ships alone proved insufficient to meet the demand. The Danes, Swedes, and even the Hanseatic towns of the eastern Baltic, having so long been under the thumb of Lübeck’s monopoly over salt from Lüneburg, were increasingly happy to accept bay salt brought by ships from the Low Countries — modern-day Belgium and the Netherlands. Indeed, when these interloping Dutch ships were attacked by Lübeck in 1438, most of the rest of the Hanseatic League refused Lübeck’s call to arms. When even the Hanseatic-installed king of Denmark sided with the Dutch as well, Lübeck decided to back down and save face. The 1441 peace treaty allowed the Dutch into the Baltic on equal terms.6 Hanseatic hegemony in the Baltic was officially over.

The Dutch, by the 1440s, had thus gained a share of the carrying trade, exchanging Atlantic bay salt for the Baltic’s grain, timber, and various naval stores like hemp for rope and pitch for caulking. But this was just the beginning.

1. Philippe Dollinger, The German Hansa, trans. D. S. Ault and S. H. Steinberg, The Emergence of International Business, 1200-1800 (Macmillan and Co Ltd, 1970), pp.219-220, 253-4.

2. L. Gittins, “Salt, Salt Making, and the Rise of Cheshire”, Transactions of the Newcomen Society 75, no. 1 (January 2005), pp.139–59; L. G. M. Bass-Becking, “Historical Notes on Salt and Salt-Manufacture”, The Scientific Monthly 32, no. 5 (1931), pp.434–46; A. R. Bridbury, England and the Salt Trade in the Later Middle Ages (Clarendon Press, 1955), pp.46-52. Incidentally, some historians, like Jonathan I. Israel, Dutch Primacy in World Trade, 1585-1740 (Clarendon Press, 1989) p.223, note occasional reports of French bay salt having been worse than the Portuguese or Spanish due to its high magnesium content, “which imparted an unattractive, blackish colour”. This must be based on a misunderstanding, however, as the salts would have been identical other than in terms of the amount of dirt taken up with the salt from the pans. At certain points in the seventeenth century the French workers skimming the salt must simply have been relatively careless compared to those of Iberia.

3. John Collins, Salt and fishery a discourse thereof (1682), pp.17, 54-5, 66-8.

4. Bridbury, pp.94-7 for estimates.

5. Karl-Gustaf Hildebrand, “Salt and Cloth in Swedish Economic History”, Scandinavian Economic History Review 2, no. 2 (1 July 1954), pp.81, 86, 91.

6. For this section see: Dollinger, pp.194-5, 201, 236, 254, 300.

June 28, 2024

Ruling Medieval France

In Quillette, Charlotte Allen reviews House of Lilies: The Dynasty That Made Medieval France by Justine Firnhaber-Baker, a period of history I know mainly from the English point of view:

I’m a PhD medievalist, but the history of medieval French royalty was never my specialty, and my ignorance was vast.

I’d assumed, for example, that the French kings of the Middle Ages were mostly fainéants whose writ scarcely ran past the Île-de-France region (encompassing the city of Paris and its environs). The English monarchy across the Channel had been centralised since the days of Alfred the Great (849–899); but the French kings seemed to rule in a more symbolic capacity, being perpetually at the mercy of the powerful dukes and counts of autonomous French regions such as Normandy, Burgundy, Aquitaine, Anjou, Blois, Toulouse, and Languedoc. These regional rulers were technically royal vassals. But, in actuality, they saw themselves as absolute rulers in their own right, and so had no compunction against turning on the crown when they thought it would further their interests.

My impressions had been formed by accounts of the 17-year-old Joan of Arc’s having to personally drag the Dauphin (the future King Charles VII) to Reims for his coronation in 1429, and by Shakespeare’s historical plays, which portrayed the French as fops incapable of defending their territory against the robust and brotherly English during the Hundred Years’ War. Indeed, the whole point of that war (from the English perspective) was that, by dynastic right, large portions of France’s fractured political landscape actually belonged to England.

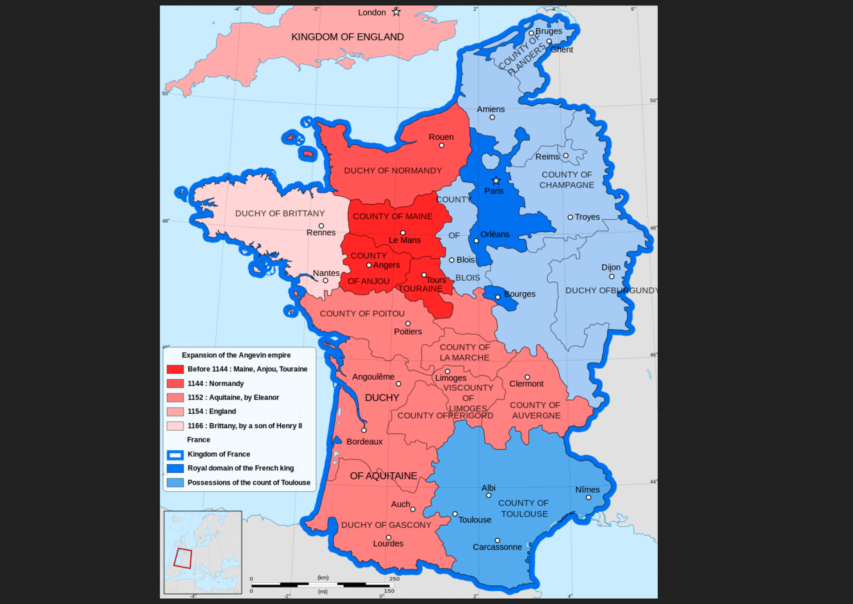

The one medieval French royal (by marriage) I did know something about, Eleanor of Aquitaine (c. 1122–1204), dumped her French husband, King Louis VII (1120–1180) after he bungled the Second Crusade, a costly and embarrassing adventure on which Eleanor had accompanied him on horseback. (“Never take your wife on a Crusade”, a medievalist friend of mine once sensibly quipped). To top off his disastrous final loss of his Crusader army in 1148 during an ill-considered attack on Damascus — which, although Muslim-ruled, was in fact an ally of Latin-Christian Jerusalem — Louis and Eleanor had failed to produce a son. No sooner was the ink dry on their divorce in 1152 (technically an annulment, since the two were Catholics), than she married Henry Plantagenet, son and heir of the duke of Anjou, who two years later became King Henry II of England. Henry quickly procreated five sons (among fourteen surviving children) with his new bride. Thus began the dynasty that would rule England for more than three centuries.

As everyone who has seen The Lion in Winter knows, Henry II’s relationship with Eleanor was far from tranquil, but two of their sons succeeded him to the English throne: Richard the Lionheart and King John (of Magna Carta fame or infamy, depending on your perspective). Henry was, besides king of England, duke of Normandy and count of Anjou, through his great-grandfather, William the Conqueror, and his mother, Matilda, who’d married Henry’s Anjevin father, Geoffrey, after her first husband, the Holy Roman Emperor Henry V, died in 1125.

Eleanor’s grounds for annulling her marriage to Louis had been that he was her fourth cousin, which violated the Catholic Church’s (selectively applied) consanguinity restrictions. But Henry was even closer kin, being her third cousin. The humiliated and (understandably) rankled Louis demanded that Henry, as his feudal vassal, explain why he’d failed to ask permission to marry (let alone marry his boss’s ex). Henry declined to reply, the feudal equivalent of declaring oneself in rebellion. Louis retaliated by invading Normandy — unsuccessfully — and trying to hold onto Eleanor’s Aquitaine on the claim that he’d become its duke by marriage (Henry II was meanwhile making the same claim) before giving up and remarrying himself in 1154.

A colour-coded political map of France during the twelfth century, indicating the early expansion of the Angevin Empire — i.e., the territorial possessions of the House of Plantagenet — from the time of Geoffrey V of Anjou (1113–1151). The Plantagenets would rule in England, and parts of France, till the demise of Richard III of England (1452–1485).

I’d assumed that French kings wouldn’t hold much in the way of real royal power until the time of King Louis XIV (1638–1715), who declared (perhaps apocryphally), L’État, c’est moi, and forced French regional nobles to reside in his over-the-top palace at Versailles (where they’d dissipate their incomes via elaborate court ceremonies instead of making trouble from their provincial power bases).

But the scales have now been knocked from my eyes, thanks to Justine Firnhaber-Baker, a professor of French medieval history at the University of St Andrews. The subtitle of her new book, House of Lilies: The Dynasty That Made Medieval France, refers to the Capetian dynasty founded by Hugh Capet (c. 940–996), who took his royal title in 987 A.D. Every French monarch, from Hugh’s reign to the French Revolution and beyond, had Capetian blood running through his veins — including the aforementioned Louis VII, who was a direct descendant of Hugh, and the bookish, dithering King Louis XVI, who was not, but who nevertheless went to the guillotine in 1793 under the derisive sobriquet “Citizen Louis Capet”.

June 1, 2024

May 13, 2024

Archaeological Publishing – the unpalatable truth

Classical and Ancient Civilization

Published May 11, 2024Some anecdotes about publishing archaeological sites

April 22, 2024

QotD: Before England could rely on the “wooden walls” of the Royal Navy

… given this general lack of geographical knowledge, try to imagine embarking on a voyage of discovery. To an extent, you might rely on the skill and experience of your mariners. For England in the mid-sixteenth century, however, these would not have been all that useful. It’s strange to think of England as not having been a nation of seafarers, but this was very much the case. Its merchants in 1550 might hop across the channel to Calais or Antwerp, or else hug the coastline down to Bordeaux or Spain. A handful had ventured further, to the eastern Mediterranean, but that was about it. Few, if any, had experience of sailing the open ocean. Even trade across the North Sea or to the Baltic was largely unknown – it was dominated by the German merchants of the Hanseatic League. Nor would England have had much to draw upon in the way of more military, naval experience. The seas for England were a traditional highway for invaders, not a defensive moat. After all, it had a land border with Scotland to the north, as well as a land border with France to the south, around the major trading port of Calais. Rather than relying on the “wooden walls” of its ships, as it would in the decades to come, the two bulwarks in 1550 were the major land forts at Calais and Berwick-upon-Tweed.

Anton Howes, “The House of Trade”, Age of Invention, 2019-11-13.

March 10, 2024

Viking longships and textiles

Virginia Postrel reposts an article she originally wrote for the New York Times in 2021, discussing the importance of textiles in history:

The Sea Stallion from Glendalough is the world’s largest reconstruction of a Viking Age longship. The original ship was built at Dublin ca. 1042. It was used as a warship in Irish waters until 1060, when it ended its days as a naval barricade to protect the harbour of Roskilde, Denmark. This image shows Sea Stallion arriving in Dublin on 14 August, 2007.

Photo by William Murphy via Wikimedia Commons.

Popular feminist retellings like the History Channel’s fictional saga Vikings emphasize the role of women as warriors and chieftains. But they barely hint at how crucial women’s work was to the ships that carried these warriors to distant shores.

One of the central characters in Vikings is an ingenious shipbuilder. But his ships apparently get their sails off the rack. The fabric is just there, like the textiles we take for granted in our 21st-century lives. The women who prepared the wool, spun it into thread, wove the fabric and sewed the sails have vanished.

In reality, from start to finish, it took longer to make a Viking sail than to build a Viking ship. So precious was a sail that one of the Icelandic sagas records how a hero wept when his was stolen. Simply spinning wool into enough thread to weave a single sail required more than a year’s work, the equivalent of about 385 eight-hour days. King Canute, who ruled a North Sea empire in the 11th century, had a fleet comprising about a million square meters of sailcloth. For the spinning alone, those sails represented the equivalent of 10,000 work years.

Ignoring textiles writes women’s work out of history. And as the British archaeologist and historian Mary Harlow has warned, it blinds scholars to some of the most important economic, political and organizational challenges facing premodern societies. Textiles are vital to both private and public life. They’re clothes and home furnishings, tents and bandages, sacks and sails. Textiles were among the earliest goods traded over long distances. The Roman Army consumed tons of cloth. To keep their soldiers clothed, Chinese emperors required textiles as taxes.

“Building a fleet required longterm planning as woven sails required large amounts of raw material and time to produce,” Dr. Harlow wrote in a 2016 article. “The raw materials needed to be bred, pastured, shorn or grown, harvested and processed before they reached the spinners. Textile production for both domestic and wider needs demanded time and planning.” Spinning and weaving the wool for a single toga, she calculates, would have taken a Roman matron 1,000 to 1,200 hours.

Picturing historical women as producers requires a change of attitude. Even today, after decades of feminist influence, we too often assume that making important things is a male domain. Women stereotypically decorate and consume. They engage with people. They don’t manufacture essential goods.

Yet from the Renaissance until the 19th century, European art represented the idea of “industry” not with smokestacks but with spinning women. Everyone understood that their never-ending labor was essential. It took at least 20 spinners to keep a single loom supplied. “The spinners never stand still for want of work; they always have it if they please; but weavers are sometimes idle for want of yarn,” the agronomist and travel writer Arthur Young, who toured northern England in 1768, wrote.

Shortly thereafter, the spinning machines of the Industrial Revolution liberated women from their spindles and distaffs, beginning the centuries-long process that raised even the world’s poorest people to living standards our ancestors could not have imagined. But that “great enrichment” had an unfortunate side effect. Textile abundance erased our memories of women’s historic contributions to one of humanity’s most important endeavors. It turned industry into entertainment. “In the West,” Dr. Harlow wrote, “the production of textiles has moved from being a fundamental, indeed essential, part of the industrial economy to a predominantly female craft activity.”

January 25, 2024

The Bathtub Hoax and debunked medieval myths

David Friedman spends a bit of time debunking some bogus but widely believed historical myths:

“Image” by Lauren Knowlton is licensed under CC BY 2.0 .

The first is a false story that teaches a true lesson — the U.S. did treat Amerinds unjustly in a variety of contexts, although the massive die off as a result of the spread of Old World diseases was a natural result of contact, not deliberate biological warfare. The second lets moderns feel superior to their ignorant ancestors; most people like feeling superior to someone.

Another example of that, deliberately created by a master, is H.L. Mencken’s bathtub hoax, an entirely fictitious history of the bathtub published in 1917:

The article claimed that the bathtub had been invented by Lord John Russell of England in 1828, and that Cincinnatian Adam Thompson became acquainted with it during business trips there in the 1830s. Thompson allegedly went back to Cincinnati and took the first bath in the United States on December 20, 1842. The invention purportedly aroused great controversy in Cincinnati, with detractors claiming that its expensive nature was undemocratic and local doctors claiming it was dangerous. This debate was said to have spread across the nation, with an ordinance banning bathing between November and March supposedly narrowly failing in Philadelphia and a similar ordinance allegedly being effective in Boston between 1845 and 1862. … Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. was claimed to have campaigned for the bathtub against remaining medical opposition in Boston; the American Medical Association supposedly granted sanction to the practice in 1850, followed by practitioners of homeopathy in 1853.

According to the article, then-Vice President Millard Fillmore visited the Thompson bathtub in March 1850 and having bathed in it became a proponent of bathtubs. Upon his accession to the presidency in July of that year, Fillmore was said to have ordered the construction of a bathtub in the White House, which allegedly refueled the controversy of providing the president with indulgences not enjoyed by George Washington or Thomas Jefferson. Nevertheless, the effect of the bathtub’s installation was said to have obliterated any remaining opposition, such that it was said that every hotel in New York had a bathtub by 1860. (Wikipedia)

Writing more than thirty years later, Mencken claimed to have been unable to kill the story despite multiple retractions. A google search for [Millard Fillmore bathtub] demonstrates that it is still alive. Among other hits:

The first bathtub placed in the White House is widely believed to have had been installed in 1851 by President Millard Fillmore (1850-53). (The White House Bathrooms & Kitchen)

Medieval

The desire of moderns to feel superior to their ancestors, helps explain a variety of false beliefs about the Middle Ages including the myth, discussed in detail in an earlier post, that medieval cooking was overspiced to hide the taste of spoiled meat.

Other examples:

Medieval witch hunts: Contrary to popular belief, large scale persecution of witches started well after the end of the Middle Ages. The medieval church viewed the belief that Satan could give magical powers to witches, on which the later prosecutions were largely based, as heretical. The Spanish Inquisition, conventionally blamed for witchcraft prosecutions, treated witchcraft accusations as a distraction from the serious business of identifying secret Jews and Muslims, dealt with such accusations by applying serious standards of evidence to them.

Chastity Belts: Supposedly worn by the ladies of knights off on crusade. The earliest known evidence of the idea of a chastity belt is well after the end of the crusades, a 15th century drawing, and while there is literary evidence for their occasional use after that no surviving examples are known to be from before the 19th century.

Ius Prima Noctae aka Droit de Seigneur was the supposed right of a medieval lord to sleep with a bride on her wedding night. Versions of the institution are asserted in a variety of sources going back to the Epic of Gilgamesh, but while it is hard to prove that it never existed in the European middle ages it was clearly never the norm.

The Divine Right of Kings: Various rulers through history have claimed divine sanction for their rule but “The Divine Right of Kings” is a doctrine that originated in the sixteenth and seventeenth century with the rise of absolute monarchy — Henry VIII in England, Louis XIV in France. Medieval rulers were absolute in neither theory or practice. The feudal relation was one of mutual obligation, in its simplest form protection by the superior in exchange for set obligations of support by the inferior. In practice the decentralized control of military power under feudalism presented difficulties for a ruler who wished to overrule the desires of his nobility, as King John discovered.

Some fictional history functions in multiple versions designed to support different causes. The destruction of the Library of Alexandria has been variously blamed on Julius Caesar, Christian mobs rioting against pagans, and the Muslim conquerors of Egypt, the Caliph Umar having supposedly said that anything in the library that was true was already in the Koran and anything not in the Koran was false. There is no good evidence for any of the stories. The library existed in classical antiquity, no longer exists today, but it is not known how it was destroyed and it may have just gradually declined.

January 3, 2024

Highlights of Diocletian’s Palace in Split

Scenic Routes to the Past

Published 6 Oct 2023A Roman historian’s tour of the Palace of Diocletian in Split, Croatia.

Chapters

0:00 Diocletian and his palace

0:59 Overview and layout

2:37 South facade

3:07 East facade

3:39 Porta Aurea

4:09 Peristyle

4:48 Temple of Jupiter

5:49 Reception rooms (vestibule and substructures)

6:23 Mausoleum of Diocletian / Cathedral

January 1, 2024

QotD: The Panto

One of the worst things my parents ever did was force me to go to the panto. It was Angela’s Ashes levels of misery memoir fodder.

What made it worse was that I was about 14; I’d almost managed to get through childhood without experiencing this strange British tradition and then, just at the age when you’re most vulnerable to cringe, I got dragged in. Anyway, I think I’m over it now.

Pantomime is one of those very British things that makes me feel a strange sense of alienation from my countrymen, like celebrating the NHS or twee. I’m glad that other people enjoy it, and that it brings a lot of work to actors and to theatres during the Christmas period. I just personally don’t get it.

For those who don’t know about the ins and outs of our island culture, panto is a sort of farcical theatre featuring lots of sexual innuendo and contemporary pop culture references; I think when I watched it there must have been one or two ex-Neighbours stars because they all finished by singing the theme tune.

A key part of this British institution is drag, with men playing the roles of Widow Twankey and the Ugly Sisters. Drag is quite an established tradition in England, such a part of popular entertainment that there is even a photograph of British soldiers in dresses fighting in the Second World War.

Pantomime is thought to have evolved from the medieval Feast of Fools, a day of the year (around the Christmas/New Year period) when social norms would be inverted; laymen would be elected bishops, lords would serve their retainers drinks, and men and women would even swap roles. Social norms could be temporarily broken, which continues today in the often risqué humour incongruously aimed at family audiences (hilariously portrayed in the Les Dennis episode of Extras.)

This kind of drag is obviously humourous, the aim being for the men to look as ridiculous as possible; think of the ungainly Bernard Bresslaw in Carry on Doctor. It is very different to the later pop culture gender fluidity pioneered by David Bowie in which males might be presented as beautifully feminine, even alluring; that was aimed at challenging and disturbing the audience, while panto is aimed at amusing and reassuring. Indeed, the whole point of spending a day inverting social norms is that, by doing so, you are implicitly accepting and defending those social norms.

This form of drag is obviously quite different to the more modern drag queen, a form of entertainment that can be far more explicit and which has in the 21st century become yet another one-of-those-talking-points, chiefly because people seem so keen on letting children watch it.

Ed West, “The last conservative moral panic”, Wrong Side of History, 2023-02-08.

December 29, 2023

The Christianization of England

Ed West‘s Christmas Day post recounted the beginnings of organized Christianity in England, thanks to the efforts of Roman missionaries sent by Pope Gregory I:

“Saint Augustine and the Saxons”

Illustration by Joseph Martin Kronheim from Pictures of English History, 1868 via Wikimedia Commons.

The story begins in sixth century Rome, once a city of a million people but now shrunk to a desolate town of a few thousand, no longer the capital of a great empire of even enjoying basic plumbing — a few decades earlier its aqueducts had been destroyed in the recent wars between the Goths and Byzantines, a final blow to the great city of antiquity. Under Pope Gregory I, the Church had effectively taken over what was left of the town, establishing it as the western headquarters of Christianity.

Rome was just one of five major Christian centres. Constantinople, the capital of the surviving eastern Roman Empire, was by this point far larger, and also claimed leadership of the Christian world — eventually the two would split in the Great Schism, but this was many centuries away. The other three great Christian centres — Jerusalem, Alexandria, and Antioch — would soon fall to Islam, a turn of events that would strengthen Rome’s spiritual position. And it was this Roman version of Christianity which came to shape the Anglo-Saxon world.

Gregory was a great reformer who is viewed by some historians as a sort of bridge between Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, the founder of a new and reborn Rome, now a spiritual rather than a military empire. He is also the subject of the one great stories of early English history.

One day during the 570s, several years before he became pontiff, Gregory was walking around the marketplace when he spotted a pair of blond-haired pagan slave boys for sale. Thinking it tragic that such innocent-looking children should be ignorant of the Lord, he asked a trader where they came from, and was told they were “Anglii”, Angles. Gregory, who was fond of a pun, replied “Non Angli, sed Angeli” (not Angles, but angels), a bit of wordplay that still works fourteen centuries later. Not content with this, he asked what region they came from and was told “Deira” (today’s Yorkshire). “No,” he said, warming to the theme and presumably laughing to himself, “de ira” — they are blessed.

Impressed with his own punning, Gregory decided that the Angles and Saxons should be shown the true way. A further embellishment has the Pope punning on the name of the king of Deira, Elle, by saying he’d sing “hallelujah” if they were converted, but it seems dubious; in fact, the Anglo-Saxons were very fond of wordplay, which features a great deal in their surviving literature and without spoiling the story, we probably need to be slightly sceptical about whether Gregory actually said any of this.

The Pope ordered an abbot called Augustine to go to Kent to convert the heathens. We can only imagine how Augustine, having enjoyed a relatively nice life at a Benedictine monastery in Rome, must have felt about his new posting to some cold, faraway island, and he initially gave up halfway through his trip, leaving his entourage in southern Gaul while he went back to Rome to beg Gregory to call the thing off.

Yet he continued, and the island must have seemed like an unimaginably grim posting for the priest. Still, in the misery-ridden squalor that was sixth-century Britain, Kent was perhaps as good as it gets, in large part due to its links to the continent.

Gaul had been overrun by the Franks in the fifth century, but had essentially maintained Roman institutions and culture; the Frankish king Clovis had converted to Catholicism a century before, following relentless pressure from his wife, and then as now people in Britain tended to ape the fashions of those across the water.

The barbarians of Britain were grouped into tribes led by chieftains, the word for their warlords, cyning, eventually evolving into its modern usage of “king”. There were initially at least twelve small kingdoms, and various smaller tribal groupings, although by Augustine’s time a series of hostile takeovers had reduced this to eight — Kent, Sussex, Essex, and Wessex (the West Country and Thames Valley), East Anglia, Mercia (the Midlands), Bernicia (the far North), and Deira (Yorkshire).

In 597, when the Italian delegation finally finished their long trip, Kent was ruled by King Ethelbert, supposedly a great-grandson of the semi-mythical Hengest. The king of Kent was married to a strong-willed Frankish princess called Bertha, and luckily for Augustine, Bertha was a Christian. She had only agreed to marry Ethelbert on condition that she was allowed to practise her religion, and to keep her own personal bishop.

Bertha persuaded her husband to talk to the missionary, but the king was perhaps paranoid that the Italian would try to bamboozle him with witchcraft, only agreeing to meet him under an oak tree, which to the early English had magical properties that could overpower the foreigner’s sorcery. (Oak trees had a strong association with religion and mysticism throughout Europe, being seen as the king of the trees and associated with Woden, Zeus, Jupiter, and all the other alpha male gods.)

Eventually, and persuaded by his wife, Ethelbert allowed Augustine to baptise 10,000 Kentish men on Christmas Day, 597, according to the chronicles. This is probably a wild exaggeration; 10,000 is often used as a figure in medieval history, and usually just means “quite a lot of people”.