We should start with a basic understanding of who we are talking about here, where they are coming from and the areas they are settling in. First we have our Greeks, who I am sure that most of our readers are generally familiar with. They don’t call themselves Greeks – it is the Romans who do (Latin: graeci); by the classical period they call themselves Hellenes (Έλληνες), a term that appears in the Iliad but once (Homer prefers Ἀχαιοί and Δαναοί, “Achaeans” and “Danaans”). That’s relevant because a lot of the apparent awareness of the Greeks (or more correctly, the Hellenes) as a distinct group, united by language and culture against other groups, belongs to late Archaic and early Classical and the phenomenon we’re going to look at begins during the Greek Dark Age (1100-800) and crests in the Archaic (800-480).

Greek settlement in the late Bronze Age (c. 1500-1100) was focused on the Greek mainland, though we have Greek (“Mycenean”) settlements on the Aegean islands (and Crete) and footholds on the west coast of Asia Minor (modern Turkey). Over the Dark Age – a period where our evidence is very poor indeed, so we cannot see very clearly – the area of Greek-speaking settlement in the Aegean expands and Greek settlements along that West coast of Asia Minor expand dramatically. Our ancient sources preserve legends about how these Greeks (particularly the Ionians, inhabiting the central part of that coastal strip) got there, having been supposedly expelled from Achaia on the northern side of the Peloponnese, but it’s unclear how seriously we should take those legends. But the key point here is that the outward motion of Greeks from mainland Greece proper begins quite early (c. 1100) and is initially local and probably not as organized as the subsequent second phase beginning in the 8th century, which is going to be our focus here.

Our other group are the Phoenicians. They did not call themselves that either; it derives from the Greeks who called them Phoinices (φοίνικες), which like the Roman Poeni may have had its roots in Egyptian fnḫw or perhaps Israelite Ponim.1 In any case, the word is old, as it appears in Linear B tablets dating to the Mycenean period (that 1500-1100 period). The Phoenicians themselves, if asked to call themselves something, would more likely have said Canaans, Kn’nm, though much like the Greeks tended to be Athenians, Spartans, Thebans and so on first, the Phoenicians tended to be Sidonians, Tyrians and so on first. They spoke a Semitic language which we call Phoenician (closely related to Biblical Hebrew) and they invented the alphabet to represent it; this alphabet was copied by the Greeks to represent their language, who were in turn copied by the Romans to represent their language, whose alphabet in turn was adopted by subsequent Europeans to represent their languages – which is the alphabet which I am writing with to you now.

Since at least the late bronze age, they lived in a series of city states on the eastern edge of the Mediterranean in Phoenicia in the Levant in what today would mostly be Lebanon. During the late bronze age, this was the great field of contested influence between the Hittite, (Middle) Assyrian and (New Kingdom) Egyptian Empires. The Late Bronze Age Collapse removed those external influences, leading to a quick recovery from the collapse and then efflorescence in the region. They had many cities, but the most important by this point are Sidon and Tyre; by the 9th century, Tyre emerged as chief over Sidon and may at times have controlled it directly, but this was short lived as the whole region came under the control of the (Neo)Assyrian Empire in 858. The Assyrians demanded heavy tribute (which may contribute to colonization, discussed below) but only vassalized rather than annexed Tyre, Byblos and Sidon, the three largest Phoenician cities.

Both the Greeks and the Phoenicians have one thing in common at the start, which is that these are societies oriented towards the sea. Their initial area of settlement is coastal and both groups were significant sea-faring societies even during the late Bronze Age and remained so by the Archaic period. Both regions, while not resource poor (Phoenicia was famous for its timber, Lebanese cedar), are not resource rich either, particularly in agricultural resources. Compared to the fertility of Mesopotamia, Egypt or even Italy, these were drier, more marginal places, which may go some distance to explaining why both societies ended up oriented towards the sea: it was there and they could use the opportunities.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Ancient Greek and Phoenician Colonization”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2023-10-13.

1. The former is what I’ve found in dictionary entries for etymologies, the latter is what Dexter Hoyos suggests, Carthaginians (2010), 1. I am not an expert on Semitic languages, linguistics or etymologies, so don’t ask me to decide between them.

May 3, 2024

QotD: Colonialism in the ancient Mediterranean

April 21, 2024

QotD: The “omni-spear” of the Mediterranean World

So I first want to suggest a set of basic characteristics for what I am going to term the “omni-spear“, the standard kind of iron-tipped one-handed thrusting spear that almost everyone fought with in the Mediterranean world.

So let us posit a spear. Its haft is made of wood – our ancient sources tend to be particular that certain kinds of wood, particularly ash and cornelian cherry (cornel wood), are best – and about 2.5 to 3m in length and roughly 2.5cm in diameter. Obviously, on one end we’ll have our iron spear head. On the other end, we probably have a smaller iron spear butt, sometimes called a ferrule.

For our spear tip, we’re going to have a hunk of iron about 250-450g in mass. It’s going to have a circular socket, about 2 to 2.5cm in diameter (to fit the haft) at its base. That socket will then proceed upwards into the tip as a “mid-ridge”, though it generally stops being entirely hollow at some point. In two directions from the mid-ridge are going to project some “blades” – if we’re French, we’ll call them flamme, “flames”, while if we’re Spanish they’ll be hoja, “blades”, and if we’re German they’re Blätter, “sheets, leaves”. These taper at the tip and widen towards the base, usually before curving gracefully inward on the socket a few inches up from its base. Often scholars have called this a “leaf shaped” spearhead, which I always find a bit awkward in phrasing (leaves can have many shapes), but the alternatives, like “tear-drop” shaped, aren’t any less awkward. If you are having a hard time conceptualizing that picture, here is an example of what I mean.

For the bottom of the spear we could just go with nothing. We could also make a simple conical socket in iron and secure it with a rivet or, if we’re being really creative, a nail hammered into the base of the shaft. If we want to be really fancy, we might make a spear-butt that combines a circular socket with a long square-sectioned projection so that it serves better as a backup point in a pinch. If you want to see the more developed version of that, here is a Greek “sauroter“, about the most elaborate this part of the spear gets.

And there we go. We have the “omni-spear”. Basic spear-butt, “leaf-shaped” spearhead with a strong mid-ridge, both generally in iron, joined by a 2.5-3m long wooden haft, about 2.5cm thick (though the haft might be thicker, as it could taper before meeting the socket) made of hardwood, with a grip at the center of balance.

That basic description describes the famous Greek dory, the spear of the hoplite. It also describes one of the more common forms of the Roman hasta, one with what I’ve termed a “Type A” Roman spearhead. And it also describes the La Tène spear, the native name of which we don’t know.1 And it also describes common thrusting spears of the Iberian Peninsula, both those used by the Iberians living in the coastal Levante and the Celtiberian peoples living on the Meseta; the names of those spears too are lost to us.2 And it also describes the common weapon of the Persian infantry, including their elite infantry which Herodotus calls “Immortals”. Almost certainly it describes spears even further afield, but we are rapidly reaching the edge of my expertise, so I’ll stop with the Persian Empire.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: The Mediterranean Iron Omni-Spear”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2023-11-10.

1. And before you jump up to tell me “oh, it was called a gaesum“, no, that’s a javelin and we do not know what sort of javelin correlates to that name preserved in our sources.

2. And before someone jumps up and tells me, “oh, it was called a soliferreum, no, that’s also a javelin and we do know exactly what sort of javelin that correlates to. They’re super cool, but they are throwing weapons, not thrusting spears. Interestingly, all over the Iberian peninsula it seems to have been standard for warriors to carry one javelin (often, but not always a soliferreum) and one thrusting spear. We find that pattern over and over again in burial deposits.

March 5, 2024

The 1st Punic War – Corvus, Rams and Drachma

Drachinifel

Published Sep 13, 2023Today we take a look at the strategy and shipping of the 1st Punic War with expert Bret Devereaux!

(more…)

February 26, 2024

Rome: Part 4 – The First Punic War 264-241 BC

seangabb

Published Feb 25, 2024This course provides an exploration of Rome’s formative years, its rise to power in the Mediterranean, and the exceptional challenges it faced during the wars with Carthage.

• Growth of Tensions between Rival Powers

• Differences of Civilisation

• The Outbreak of War

• The Course of War

• Growth of Roman Sea Power

• The End and Significance of the War

(more…)

January 20, 2024

Why Tyrian Purple Dye Is So Expensive | So Expensive | Insider Business

Insider Business

Published 21 Jan 2023Making authentic Tyrian purple dye starts with extracting a murex snail gland. After a series of painstaking steps, Tunisian dye maker Mohamed Ghassen Nouira turns as much as 45 kilograms of snails into a single gram of pure Tyrian purple extract. When he’s done, he can sell it for $2,700. Some retailers sell a gram of the pigment for over $3,000. In comparison, 5 grams of synthetic Tyrian purple costs under $4.

So, why is real Tyrian purple so hard to make? And is that why it’s so expensive?

(more…)

January 13, 2024

History RE-Summarized: The Byzantine Empire

Overly Sarcastic Productions

Published 29 Sept 2023The Byzantines (Blue’s Version) – a project that took an almost unfathomable amount of work and a catastrophic 120+ individual maps. I couldn’t be happier.

SOURCES & Further Reading:

“Byzantium” I, II, and III by John Julius Norwich, The Byzantine Republic: People and Power in New Rome by Anthony Kaldellis, The Alexiad by Anna Komnene, Osman’s Dream: The History of the Ottoman Empire by Caroline Finkel, Sicily: An Island at the Crossroads of History by John Julius Norwich, A History of Venice by John Julius Norwich. I also have a degree in classical civilization.Additionally, the most august of thanks to our the members of our discord community who kindly assisted me with so much fantastic supplemental information for the scripting and revision process: Jonny, Catia, and Chehrazad. Thank you for reading my nonsense, providing more details to add to my nonsense, and making this the best nonsense it can be.

(more…)

November 24, 2023

QotD: “Citizenship” in the ancient and classical world

… before we dive into how Roman citizenship worked, we need to have a baseline for how citizenship worked in most ancient polities so we can get a sense of the way Roman citizenship is typical and the ways that it is different. In the broader ancient Mediterranean world, citizenship was generally a feature of self-governing urban polities (“city-states”). Though I am going to use Athens as my “type model” here, citizenship was not exclusively Greek; Italic communities; Carthage seems to have had a very similar system. That said, our detailed knowledge of the laws of many of the smaller Greek poleis is very limited; we only know that the Athenian system was regarded more-or-less as “typical” (as opposed to Sparta, consistently regarded as unusual or strange, though even more closed to new entrants than Athens).

Citizenship status was clearly extremely important to the ancients whose communities had it. Greek and Roman writers, for instance, do not generally write that “Athens” or “Carthage” do something (go to war, make peace, etc), but rather that “the Athenians” or “the Carthaginians” do so – the body of citizens acts, not the state. Only citizens (or more correctly, adult citizen-males) were permitted to engage in direct political activity – voting, speaking in the assembly, or holding office – in a Greek polis; at Athens, for a non-citizen to do any of these things (or to pretend to be a citizen) carried the death penalty. This status was a jealously guarded one. It had other legal privileges; as early as Draco’s homicide law (laid down in 622/1) it is clear that there were legal advantages to Athenian citizenship. After Solon (Archon in 594), Athenian citizens became legally immune to being reduced to slavery; non-citizen foreigners who fell into debt were apparently not so protected (for more on this, see S. Lape, Race and Citizen Identity in the Classical Athenian Democracy (2010), 9ff). Citizenship, for those who had it, was likely the most important communal identity they had – certainly more so than linguistic or ethnic connections (an Athenian was an Athenian first, a Greek a distant second).

So then who got to be a citizen? At Athens, the rules changed a little over time. Solon’s reforms may mark the point at which citizenship became the controlling identity (Lape, op. cit. makes this argument). While Solon himself briefly opened up Athenian citizenship to migrants with useful skills, that door was soon slammed shut (Plut. Sol. 24.2); citizenship was largely limited to children with both a citizen father and a citizen mother (this seems to have been more flexible early on but was codified into law in 451/0 by Pericles). Bastards (the Greek term is nothoi) were barred from the citizenship at least from the reforms of Cleisthenes in 509/8. This exclusivity was not unique to Athens; recall that Spartiate status worked the same way (albeit covering an even smaller class of people). Likewise, our Latin sources on Carthage – no Carthaginian account of their government (or indeed any Carthaginian literature) survives – suggest that only Carthaginians whose descent could be traced to the founding settlers had full legal rights. Under the reforms of Cleisthenes (509/8), each Athenian, upon coming of age, had their claim to citizenship assessed by the members of their respective deme (a legally defined neighborhood) to determine if they were of Athenian citizen stock on both sides.

It is worth discussing the implication of those rules. The rules of Athenian citizenship imagine the citizen body as a collection of families, recreating itself, generation to generation, with perhaps occasional expulsions, but with minimal new entrants. Citizens only married other citizens because that was the only condition under which they could have valid citizen children. Such a policy creates a legally defined ethnic group that is – again, legally – incapable of incorporating or mixing with other groups. In this sense, Athenian citizenship, like most ancient citizenship, was radically exclusionary. Thousands of people lived permanently in Athens – resident foreigners called metics – with no hope of ever gaining Athenian citizenship, because there were no formal channels to ever do so.

(As an aside, it was possible for the Athenian citizenry to admit new members, but only by an act of the Ekklesia, the Athenian assembly. For a modern sense of what that means, imagine if it was only possible to become an American citizen by an act of Congress (good luck with the 60 votes to break a filibuster!) that names you, specifically as a new citizen. We don’t know exactly how many citizens were so admitted into the Athenian citizen body, but it was clearly very low – probably only a few hundred through the entire fourth century, for instance. In practice, this was a system where there were no formal mechanisms for naturalizing new citizens at all, that only occasionally made very specific exceptions for individuals or communities.)

In short, while there were occasional exceptions where the doorway to citizenship in a community might open briefly, in practice the citizen body in a Greek polis was a closed group of families which replaced themselves through the generations but did not admit new arrivals and instead prided themselves on the exclusive value of the status they held. The fact that the citizen body of these poleis couldn’t expand to admit new members or incorporate new communities but had become calcified and frozen would eventually doom the Greeks to lose their independence, since polities of such small size could not compete in the world of great kingdoms and empires that emerged with Philip II and Alexander.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: The Queen’s Latin or Who Were the Romans, Part II: Citizens and Allies”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2021-06-25.

November 20, 2023

QotD: Flax and linen in the ancient and medieval world

Linen fabrics are produced from the fibers of the flax plant, Linum usitatissimum. This common flax plant is the domesticated version of the wild Linum bienne, domesticated in the northern part of the fertile crescent no later than 7,000 BC, although wild flax fibers were being used to produce textiles even earlier than that. Consequently the use of linen fibers goes way back. In fact, the oldest known textiles are made from flax, including finds of fibers at Nahal Hemar (7th millennium BC), Çayönü (c. 7000 BC), and Çatalhöyük (c. 6000 BC). Evidence for the cultivation of flax goes back even further, with linseed from Tell Asward in Syria dating to the 8th millennium BC. Flax was being cultivated in Central Europe no later than the second half of the 7th millennium BC.

Flax is a productive little plant that produces two main products: flax seeds, which are used to produce linseed oil, and the bast of the flax plant which is used to make linen. The latter is our focus here so I am not going to go into linseed oil’s uses, but it should be noted that there is an alternative product. That said, my impression is that flax grown for its seeds is generally grown differently (spaced out, rather than packed together) and generally different varieties are used. That said, flax cultivated for one purpose might produce some of the other product (Pliny notes this, NH 19.16-17)

Flax was a cultivated plant (which is to say, it was farmed); fortunately we have discussed quite a bit about farming in general already and so we can really focus in on the peculiarities of the flax plant itself; if you are interested in the activities and social status of farmers, well, we have a post for that. Flax farming by and large seems to have involved mostly the same sorts of farmers as cereal farming; I get no sense in the Greco-Roman agronomists, for instance, that this was done by different folks. Flax farming changed relatively little prior to mechanization; my impression reading on it is that flax was farmed and gathered much the same in 1900 BC as it was in 1900 AD. In terms of soil, flax requires quite a lot of moisture and so grows best in either deep loam or (more commonly used in the ancient world, it seems) alluvial soils; in both cases, it should be loose, unconsolidated “sandy” (that is, small particle-sized) soil. Alluvium is loose, often sandy soil that is the product of erosion (that is to say, it is soil composed of the bits that have been eroded off of larger rocks by the action of water); the most common place to see lots of alluvial soil are in the flood-plains of rivers where it is deposited as the river floods forming what is called an alluvial plain.

Thus Pliny (NH 19.7ff) when listing the best flax-growing regions names places like Tarragona, Spain (with the seasonally flooding Francoli river) or the Po River Basin in Italy (with its large alluvial plain) and of course Egypt (with the regular flooding of the Nile). Pliny notes that linen from Sætabis in Spain was the best in Europe, followed by linens produced in the Po River Valley, though it seems clear that the rider here “made in Europe” in his text is meant to exclude Egypt, which would have otherwise dominated the list – Pliny openly admits that Egyptian flax, while making the least durable kind of linen (see below on harvesting times) was the most valuable (though he also treats Egyptian cotton which, by his time, was being cultivated in limited amounts in the Nile delta, as a form of flax, which obviously it isn’t). Flax is fairly resistant to short bursts of mild freezing temperatures, but prolonged freezes will kill the plants; it seems little accident that most flax production seems to have happened in fairly warm or at least temperate climes.

Flax is (as Pliny notes) a very fast growing plant – indeed, the fastest growing crop he knew of. Modern flax grown for fibers is generally ready for harvesting in roughly 100 days and this accords broadly with what the ancient agronomists suggest; Pliny says that flax is sown in spring and harvested in summer, while the other agronomists, likely reflecting practice further south suggest sowing in late fall and early winter and likewise harvesting relatively quickly. Flax that is going to be harvested for fibers tended to be planted in dense bunches or rows (Columella notes this method but does not endorse it, De Rust. 2.10.17). The reason for this is that when placed close together, the plants compete for sunlight by growing taller and thinner and with fewer flowers, which maximizes the amount of stalk per plant. By contrast, flax planted for linseed oil is more spaced out to maximize the number of flowers (and thus the amount of seed) per plant.

Once the flax was considered ready for harvest, it was pulled up out of the ground (including the root system) in bunches in handfuls rather than as individual plants […] and then hung to dry. Both Pliny and Columella (De Rust. 2.10.17) note that this pulling method tended to tear up the soil and regarded this as very damaging; they are on to something, since none of the flax plant is left to be plowed under, flax cultivation does seem to be fairly tough on the soil (for this reason Columella advises only growing flax in regions with ideal soil for it and where it brings a good profit). The exact time of harvest varies based on the use intended for the flax fibers; harvesting the flax later results in stronger, but rougher, fibers. Late-pulled flax is called “yellow” flax (for the same reason that blond hair is called “flaxen” – it’s yellow!) and was used for more work-a-day fabrics and ropes.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Clothing, How Did They Make It? Part I: High Fiber”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2021-03-05.

August 27, 2023

QotD: Getting food to market in pre-modern societies

The most basic kind of transport is often small-scale overland transport, either to and from the nearest city, or in small (compared to what we’ll discuss in a moment) caravans moving up and down a region […]. The Talmud, for instance, seems to suggest that much of the overland grain trade in Palestine under the Romans was performed with itinerant donkey-drivers in small caravans – and I do mean small. Egyptian tax evidence suggests that most caravans were small; Erdkamp notes that 90% of donkey caravans and 75% of camel caravans consisted of three or less animals. These sorts of small caravans don’t usually specialize in any particular good but instead function like land-based cabotage traders, buying whatever seems likely to turn a profit at each stop and stopping in each town and market along the way. Some farmers might even do this during the off season; in Spain, peasants often worked as muleteers during the slow farming season, moving rents and taxes into town or to points of export for their wealthy landlords and neighbors.

Truly long-distance bulk grain transport overland wasn’t viable for reasons we’ve actually already discussed. There is simply nothing available in the pre-modern period to carry the grain overland that doesn’t also eat it. While moving grain short distances (especially to simply fill capacity while the main profit is in other, lower-bulk, higher value goods) can be efficient enough, at long distance, all of the grain ends up eaten by the animals or people moving it.

The seaborne version of this sort of itinerant, short-distance trade is called cabotage. Now today cabotage has a particular, technical legal meaning, but when we use this word in the past, it refers not to the legal status of a ship but a style of shipping using small boats to move mixed cargo up and down the coast. In essence, cabotage works much the same as the small caravans – the merchant buys in each port whatever looks likely to turn a profit and sells whatever [is] in demand. By keeping a mixed cargo of many different sorts of things, he protects against risk – he’s always likely to be able to sell something in his boat for a profit. Such traders generally work on very short distances, often connecting smaller ports which simply cannot accommodate larger, deeper-draft long-distance traders. Such cabotage trading was the background “hum” of commerce on many pre-modern coastlines and might serve to move grain up or down the coast, although not very much of it. Remember that grain is a bulk commodity, and cabotage traders, by definition, are moving small volumes.

But when it comes to moving large volumes, the sea changes everything. The fundamental problem with transporting food on land is that the energy to transport the food must come from food, either processed into muscle power by porters or animals. But at sea, that energy can come from the wind. So while the crew of a ship eats the food, the ship can be scaled up without scaling up the food requirements of the crew or the crew itself. At the same time, sea-transit is much faster than land transit and that speed is obtained from the wind without further inputs of food. It is hard to overstate how tremendous a change in context this is. Using the figures from the Price Edict of Diocletian, we tend to estimate that river transport was five times cheaper than land transport, and sea-transport was twenty times cheaper than land transport. So while the transport of bulk goods like grain on land was limited to fairly small amounts moving over short distances – say from the farm to the nearest town or port – grain could be moved long distances en masse by sea.

Now the scale and character of long-distance transport is heavily impacted by the political realities of the local waterways. If the seas are politically divided, or full of pirates, it is going to be hard to operate big, slow vulnerable grain-freighters and still make a profit after some of them get seized, pirated or sunk. But when we have periods of political unity and relatively safe seas, we see that this sort of transport can reach quite impressive scale. For instance the port regulations of late Hellenistic and Roman Thasos – itself a decent sized, but by no means massive port – divided its harbor into two areas, one for ships carrying 80-130 tons of cargo and one for ships 130+ tons (those regulations are SEG XVII 417). A brief bit of math indicates that the distribution of free grain in the city of Rome – likely less than a third of the total grain demands of the city – required the import, by sea of some 630 tons of grain per day through the sailing season. The scale of grain shipment in the back half of the Middle Ages (post-1000 or so) was also on a vast scale, with trade-oriented Italian cities exploding in population as they imported grain (Genoa being particularly well known for this, but by no means alone in it); with that came the reemergence of truly large grain-freighters.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Bread, How Did They Make It? Part IV: Markets, Merchants and the Tax Man”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2020-08-21.

July 8, 2023

The Perfect D-Day That History Forgot

Real Time History

Published 7 Jul 2023The summer of 1944 saw the Allies land in France not once but twice. Two months after Operation Overlord, the Allies also landed in Southern France during Operation Dragoon. It was “the perfect landing” and opened up the important ports of Marseille and Toulon for Allied logistics.

(more…)

February 5, 2023

QotD: Annual cycles of plenty and scarcity in pre-modern agricultural societies

This brings us to the most fundamental fact of rural life in the pre-modern world: the grain is harvested once a year, but the family eats every day. Of course that means the grain must be stored and only slowly consumed over the entire year (with some left over to be used as seed-grain in the following planting). That creates the first cycle in agricultural life: after the harvest, food is generally plentiful and prices for it are low […] As the year goes on, food becomes scarcer and the prices for it rise as each family “eats down” their stockpile.

That has more than just economic impacts because the family unit becomes more vulnerable as that food stockpile dwindles. Malnutrition brings on a host of other threats: elevated risk of death from injury or disease most notably. Repeated malnutrition also has devastating long-term effects on young children […] Consequently, we see seasonal mortality patterns in agricultural communities which tend to follow harvest cycles; when the harvest is poor, the family starts to run low on food before the next harvest, which leads to rationing the remaining food, which leads to malnutrition. That malnutrition is not evenly distributed though: the working age adults need to be strong enough to bring in the next harvest when it comes (or to be doing additional non-farming labor to supplement the family), so the short rations are going to go to the children and the elderly. Which in turn means that “lean” years are marked by increased mortality especially among the children and the elderly, the former of which is how the rural population “regulates” to its food production in the absence of modern birth control (but, as an aside: this doesn’t lead to pure Malthusian dynamics – a lot more influences the food production ceiling than just available land. You can have low-equilibrium or high-equilibrium systems, especially when looking at the availability of certain sorts of farming capital or access to trade at distance. I cannot stress this enough: Malthus was wrong; yes, interestingly, usefully wrong – but still wrong. The big plagues sometimes pointed to as evidence of Malthusian crises have as much if not more to do with rising trade interconnectedness than declining nutritional standards). This creates yearly cycles of plenty and vulnerability […]

Next to that little cycle, we also have a “big” cycle of generations. The ratio of labor-to-food-requirements varies as generations are born, age and die; it isn’t constant. The family is at its peak labor effectiveness at the point when the youngest generation is physically mature but hasn’t yet begun having children (the exact age-range there is going to vary by nuptial patterns, see below) and at its most vulnerable when the youngest generation is immature. By way of example, let’s imagine a family (I’m going to use Roman names because they make gender very clear, but this is a completely made-up family): we have Gaius (M, 45), his wife, Cornelia (39, F), his mother Tullia (64, F) and their children Gaius (21, M), Secundus (19, M), Julia1 (16, F) and Julia2 (14, F). That family has three male laborers, three female laborers (Tullia being in her twilight years, we don’t count), all effectively adults in that sense, against 7 mouths to feed. But let’s fast-forward fifteen years. Gaius is now 60 and slowing down, Cornelia is 54; Tullia, we may assume has passed. But Gaius now 36 is married to Clodia (20, F; welcome to Roman marriage patterns), with two children Gaius (3, M) and Julia3 (1, F); Julia1 and Julia2 are married and now in different households and Secundus, recognizing that the family’s financial situation is never going to allow him to marry and set up a household has left for the Big City. So we now have the labor of two women and a man-and-a-half (since Gaius the Elder is quite old) against six mouths and the situation is likely to get worse in the following years as Gaius-the-Younger and Clodia have more children and Gaius-the-Elder gets older. The point of all of this is to note that just as risk and vulnerability peak and subside on a yearly basis in cycles, they also do this on a generational basis in cycles.

(An aside: the exact structure of these generational patterns follow on marriage patterns which differ somewhat culture to culture. In just about every subsistence farming culture I’ve seen, women marry young (by modern standards) often in their mid-to-late teens, or early twenties; that doesn’t vary much (marriage ages tend to be younger, paradoxically, for wealthier people in these societies, by the by). But marriage-ages for men vary quite a lot, from societies where men’s age at first marriage is in the early 20s to societies like Roman and Greece where it is in the late 20s to mid-thirties. At Rome during the Republic, the expectation seems to have been that a Roman man would complete the bulk of their military service – in their twenties and possibly early thirties – before starting a household; something with implications for Roman household vulnerability. Check out Rosenstein, op. cit. on this).

On top of these cycles of vulnerability, you have truly unpredictable risk. Crops can fail in so many ways. In areas without irrigated rivers, a dry spell at the wrong time is enough; for places with rivers, flooding becomes a concern because the fields have to be set close to the water-table. Pests and crop blights are also a potential risk factor, as of course is conflict.

So instead of imagining a farm with a “standard” yield, imagine a farm with a standard grain consumption. Most years, the farm’s production (bolstered by other activities like sharecropping that we’ll talk about later) exceed that consumption, with the remainder being surplus available for sale, trade or as gifts to neighbors and friends. Some years, the farm’s production falls short, creating that shortfall. Meanwhile families tend to grow to the size the farm can support, rather than to the labor needs the farm has, which tends to mean too many hands (and mouths) and not enough land. Which in turn causes the family to ride a line of fairly high risk in many cases.

All of this is to stress that these farmers are looking to manage risk through cycles of vulnerability […]

I led in with all of that risk and vulnerability because without it just about nothing these farmers do makes a lot of sense; once you understand that they are managing risk, everything falls into place.

Most modern folks think in terms of profit maximization; we take for granted that we will still be alive tomorrow and instead ask how we can maximize how much money we have then (this is, admittedly, a lot less true for the least fortunate among us). We thus tend to favor efficient systems, even if they are vulnerable. From this perspective, ancient farmers – as we’ll see – look very silly, but this is a trap, albeit one that even some very august ancient scholars have fallen into. These are not irrational, unthinking people; they are poor, not stupid – those are not the same things.

But because these households wobble on the edge of disaster continually, that changes the calculus. These small subsistence farmers generally seek to minimize risk, rather than maximize profits. After all, improving yields by 5% doesn’t mean much if everyone starves to death in the third year because of a tail-risk that wasn’t mitigated. Moreover, for most of these farmers, working harder and farming more generally doesn’t offer a route out of the small farming class – these societies typically lack that kind of mobility (and also generally lack the massive wealth-creation potential of industrial power which powers that kind of mobility). Consequently, there is little gain to taking risks and much to lose. So as we’ll see, these farmers generally sacrifice efficiency for greater margins of safety, every time.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Bread, How Did They Make It? Part I: Farmers!”, A collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2020-07-24.

December 16, 2022

Coming of the Sea Peoples: Part 1 – Prelude

seangabb

Published 1 May 2021The Late Bronze Age is a story of collapse. From New Kingdom Egypt to Hittite Anatolia, from the Assyrian Empire to Babylonia and Mycenaean Greece, the coming of the Sea Peoples is a terror that threatens the end of all things. Between April and July 2021, Sean Gabb explored this collapse with his students. Here is one of his lectures. All student contributions have been removed.

More by Sean Gabb on the Ancient World: https://www.classicstuition.co.uk/

Learn Latin or Greek or both with him: https://www.udemy.com/user/sean-gabb/

His historical novels (under the pen name “Richard Blake”): https://www.amazon.co.uk/Richard-Blak…

November 8, 2022

Look at Life — Underwater Menace (1969)

PauliosVids

Published 20 Nov 2018Dealing with the hazardous legacy of World War II.

September 19, 2022

City Minutes: Crusader States

Overly Sarcastic Productions

Published 13 May 2022Crusading is one thing, but holding your new kingdoms is a much trickier business. See how the many Christian states of “Outremer” rolled with the punches to evolve in form and function over multiple centuries.

(more…)

September 11, 2022

Are we looking at a modern equivalent to the Bronze Age Collapse?

If you’re feeling happy and optimistic, Theophilus Chilton has a bucket of cold water to douse you with:

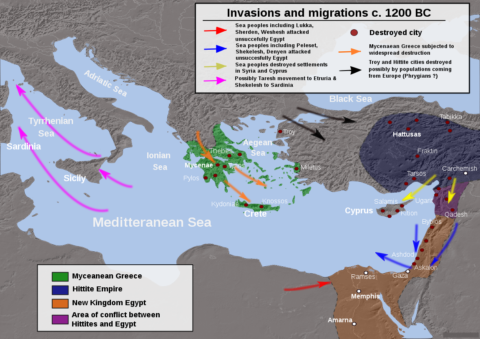

Migrations, invasions and destructions during the end of the Bronze Age (c. 1200 BC), based on public domain information from DEMIS Mapserver.

Map by Alexikoua via Wikimedia Commons.

Regular readers know that I’ve talked about collapse (as well as the implied regeneration that follows it) on here a lot. In nearly all cases, though, I’ve discussed it within a specifically American context – the collapse of the present American system and the potential for one or more post-American successor states arising in place of the present globohomo order. However, we should recognise that collapse is a general phenomenon that affects any and all large nations eventually. Just as America is not a special snowflake who is exempt from the laws of demographic-structural theory, so also is she not the only one subject to them.

Further in this vein, we should recognise that no major nation is isolated from its neighbours. No matter how self-sufficient, sooner or later everybody gets hooked up into trade networks. As trade networks expand, you develop world systems that display increased international interconnectedness and interdependency. From a demographic-structural perspective, the interconnectedness of these global systems acts to “synch up” the secular cycles of the nations involved as “information flows” increase. The upside to this is that when one part of the system prospers, everyone does. The downside, of course, is that when one part collapses, everyone does as well.

There are several historical examples of this kind of interconnected system synching up and then collapsing. Probably one of the most well-known examples would be the Bronze Age collapse which occurred in the Mediterranean world system roughly between 1225-1150 BC. Likely due to several shocks to the system working in tandem (drought, volcanic eruptions, migrations into the Balkans from the north, etc.), a series of invasions of the Sea Peoples spread out across the entire eastern end of the Mediterranean, toppling Mycenaean Greece and the Hittite Empire, and nearly did the same to Egypt. From there, the shocks moved outward throughout the rest of Anatolia and Syro-Palestine and eastward into Mesopotamia, disrupting the entire interconnected trade network. The system was apparently already primed to be toppled by these jolts, however, due to the top-heavy political structures (elite overproduction) and overspecialisation in these empires that contributed to their fragility in the face of system shocks. When the first one fell, the effects spread out like dominoes falling in a row.

There is evidence that this collapse extended beyond the Mediterranean basin and disrupted the civilisation existing in the Nordic Bronze Age around the Baltic Sea. Right around the same time that Bronze Age Mediterranean society was collapsing, serious changes to society in the Baltic basin were also taking place, primarily due to the disruption of trade routes that connected the two regions, with amber flowing south and metals and prestige goods returning north. During this period, the population in the area transitioned from a society organised primarily around scattered villages and farms into one that became more heavily militarised and centred around fortified towns, indicating that there was a change in the region’s elite organisation, or at least a strong modification of it (remember that collapse phases are characterised by struggles between competing elite groups). A large battle that dates to this era has been archaeologically uncovered in the Tollense Valley of northeastern Germany which is thought to have involved over 5000 combatants — a huge number for this area at this time, indicating more centralised state-like organisational capacities than were previously thought to have existed in the region. All in all, the evidence seems to suggest that this culture underwent some type of collapse phase at this time, likely in tandem with that occurring further south.

Other times and places have also seen such world system collapses take place. for instance, when the western Roman Empire was falling in the 3rd-5th centuries AD, the entire Mediterranean basis (again) underwent a systemwide socioeconomic collapse and decentralisation. More recently, the entire Eurasian trade system, from England to China, underwent a synchronised collapse phase in the early 17th century AD that saw revolutions, elite conflict, decentralisation, and social simplification take place across the length of the continent.

The great irony of interconnectedness is that too much of it actually works to reduce resilience within a system. Because an intensively globalised world system entails a lot of specialisation as different parts begin to focus on the production of different commodities needed within the network, this makes each part of the system more dependent upon the others. This works to reduce the resiliency of each of these individual parts, and the greater interconnectedness allows failure in one part to be communicated more widely and rapidly to other parts than might otherwise be the case in less interconnected systems.