The opening of Demons tries to fool you into thinking it’s a comedy of manners about liberal, cosmopolitan Russian aristocrats in the 1840s. The vibe is that of a Jane Austen novel, but hidden within the comforting shell of a society tale, there’s something dark and spiky. Dostoevsky pokes fun at his characters in ways that translate alarming well into 2020s America. Everybody wants to #DefundTheOkhrana and free the serfs, but is terrified that the serfs might move in next door. Characters move to Brookl … I mean to St. Petersburg to start a left-wing magazine and promptly get canceled by other leftists for it. Academics endlessly posture as the #resistance to a tyrannical sovereign (who is unaware of their existence), and try to get exiled so they can cash in on that sweet exile clout. There are polycules.1

As the book unfolds, the satire gets more and more brutal. The real Dostoevsky knew this scene well — remember he spent his early years as a St. Petersburg hipster literary magazine guy himself — and he roasts it with exquisite savagery. As a friend who read the book with me put it: the men are fatuous, deluded about their importance, lazy, their liberal politics a mere extension of their narcissism. The woman are bitchy, incurious about the world except as far as it’s relevant to their status-chasing, viewing everyone and everything instrumentally. Nobody has any actual beliefs, and everybody is motivated solely by pretension and by the desire to sneer at their country.

But this is no conservative apologia for the system these people are rebelling against either, Dostoevsky’s poison pen is omnidirectional. Many right-wing satirists are good at showing us the debased preening and backbiting, like crabs in a bucket, that surplus elites fall into when there’s a vacuum of authority. But Dostoevsky admits what too many conservatives won’t, that the libs can only do this stuff because the society they despise is actually everything that they say it is: rotting from the inside, unjust, corrupt, and worst of all ridiculous. Thus he introduces representatives of the old order, like the conceited and slow-witted general who constantly misses the point and gets offended by imagined slights. Or like the governor of the podunk town where the action takes place, who instead of addressing the various looming disasters, sublimates his anxiety over them into constructing little cardboard models.2 If there’s a vacuum of authority, it’s because men like these are undeserving of it, failing to exercise it, allowing it to slip through their fingers.

All of this is very fun,3 and yet not exactly what I expect from a Dostoevsky novel. It’s a little … frivolous? Where are the agonizingly complex psychological portraits, the weighty metaphysical debates, the surreal stroboscopic fever-dreams culminating in murder, the 3am vodka-fueled conversations about damnation? Don’t worry, it’s coming, he’s just lulling you into a false sense of security. After a few hundred pages a thunderbolt falls, the book takes a screaming swerve into darkness, and you realize that the whole first third of this novel is like the scenes at the beginning of a horror movie where everybody is walking around in the daylight, acting like stuff is normal and ignoring the ever-growing threat around them.

John Psmith, “REVIEW: Demons, by Fyodor Dostoevsky”, Mr. and Mrs. Psmith’s Bookshelf, 2023-07-17.

1. In an incredible bit of translation-enabled nominative determinism, the main cuckold is a character named Virginsky. I kept waiting for a “Chadsky” to show up, but alas he never did.

2. Look, the fact that he’s sitting there painting minis while the world burns makes the guy undeniably relatable. If you transported him to the present day he would obviously be an autistic gamer, and some of my best friends, etc., etc. Nevertheless, though, he should not be the governor.

3. For some reason, there are people who are surprised that Demons is funny. I don’t know why they’re surprised, Dostoevsky is frequently funny. The Brothers Karamazov is hilarious!

December 31, 2024

QotD: Pre-revolution Russia satirized by Dostoevsky

November 26, 2024

Orwell is more relevant now than at any time since his death

I’m delighted to find that Andrew Doyle shares my preference for Orwell the essayist over Orwell the novelist:

It is not without justification that Animal Farm (1945) and Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949) have become the keystones of George Orwell’s legacy. Personally, I’ve always favoured his essays, more often quoted than read in full. I recently wrote an article about his essays for the Washington Post, focusing on their relevance to today’s febrile political climate. You can read the article here. I would draw particular attention to the multitude of comments from left-wing readers who are apparently outraged at my argument (actually, Orwell’s argument) that authoritarianism is not specific to any one political tribe. They seem oddly determined to prove the point.

Orwell is unrivalled on the topic of the human instinct for oppressive behaviour, but his essays are far more wide-ranging than that. In these little masterworks, one senses a great thinker testing his own theses, forever fluctuating, refining his views in the very act of writing. The essays span the last two decades of his life, offering us the most direct possible insight into this unique mind.

[…]

I find Orwell’s disquisitions on literature to be among his most rewarding. “All art is propaganda”, he declares in his extended piece on Charles Dickens (1940) [link]. This conviction, flawed as is it, accounts for his determination to focus less on Dickens’s literary merits and more on his class consciousness, which is found wanting. Even better is Orwell’s rebuttal to Tolstoy’s strangely literal-minded reading of Shakespeare (1947’s “Lear, Tolstoy and the Fool” [link]), which is so rhetorically deft that it seems to settle the matter for good.

Another impressive essay, “Inside the Whale” (1940) [link], opens with a glowing assessment of Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer (1935) but soon broadens its range to cover many contemporary novelists and their approach to social commentary. The title is a reference to Miller’s remarks on the Biblical tale of Jonah, suggesting that life inside the whale has much to recommend it. Orwell puts it this way:

There you are, in the dark, cushioned space that exactly fits you, with yards of blubber between yourself and reality, able to keep up an attitude of the completest indifference, no matter what happens.

Orwell invites us to imagine that the whale is transparent, and so writers of Miller’s ilk may snuggle contentedly within, observing without interacting, recording snapshots of the world as it bounces by. This kind of inaction is anathema to Orwell, whose every written word seems to be driving towards the enactment of social change.

Orwell’s essays often serve as a cudgel to batter his detractors. He dislikes homosexuals, or those “fashionable pansies” who lack the masculine vigour to take up arms in defence of their country. He displays a similar lack of patience for the imperialistic middle-class “Blimps” and the anti-patriotic left-wing intelligentsia, or indeed anyone who adheres slavishly to any given political ideology. His work bears much of the stamp of the old left; that mix of social conservatism and economic leftism that we see most powerfully expressed in his 1941 essay “The Lion and the Unicorn” [link]. Bad writing is also a recurring bugbear; Orwell’s loathing of cliché and “ready-made metaphors” is one of the reasons his own prose style is so effervescent.

[…]

When Orwell pessimistically refers to “the remaining years of free speech”, one cannot help but be reminded of the increasingly authoritarian tendencies of today’s British government. He expresses irritation that more writers are not wielding their pens in the service of improving society. His own work, by contrast, is what he would term “constructive”, profoundly moral, and purposefully crafted in the hope of actuating real-world change. While other writers resigned themselves to a life inside the whale, Orwell was determined to cut his way out.

September 20, 2024

QotD: The Matrix, Harry Potter and “The One Pop Culture Thing”

Part of the appeal of Harry Potter must be that can somehow be intellectualized, though — at least, if the number of people incorporating it, in all apparent seriousness, into college classes can be believed. Here again, I’m not talking the English Department, which might have a legitimate reason — to study the narrative technique or whatever (for certain stretched-farther-than-Trigglypuff’s-sweatpants values of “legitimate”, anyway). I mean classes like “PHIL 101: Harry Potter and Philosophy”, which started showing up first in goofy California colleges, then all over the damn place, somewhere around 2002.

That certainly seems to be the appeal of The Matrix, and indeed The Matrix stopped being The One Pop Culture Thing very quickly, I hypothesize, because it made “intellectualizing” it too easy. The Matrix is pretty much just Jean Baudrillard: The Movie, and while that’s fun and even useful — Baudrillard did have a point, despite it all — it’s just too clever … by which I mean, The Matrix did too much of the heavy lifting, so that you don’t get too many Very Clever Persyn points for noting that we’re all, just, like, simulations in other people’s minds, dude. Descartes can go fuck himself; Keanu Reeves has solved the mind-body problem with kung fu.

Also, Baudrillard-lite is everywhere now. We’re all Postmodernists, in the same way we’re all Marxists, so even the kids who slept through most of their one required Humanities course has at least vaguely heard of this stuff. A show like True Detective, on the other hand, hearkens back to much older philosophy — as tiresome as the wannabe-Foucaults were back in the late 1980s, as a culture we’ve pretty much forgotten about them, so the brooding wannabe existentialist douchebag seems new now. I just googled up “best true detective quotes”. Here’s a small sampling:

This is a world where nothing is solved. You know, someone once told me time is a flat circle. Everything we’ve ever done or will do, we’re gonna do over and over and over again.

Also:

… to realize that all your life, all your love, all your hate, all your memory, all your pain, it was all the same thing. It was all the same dream you had inside a locked room — a dream about being a person. And like a lot of dreams, there’s a monster at the end of it.

That “flat circle” thing is a direct quote from Schopenhauer, I’m pretty sure, and the idea of “eternal recurrence” came from Vedic philosophy via him to Nietzsche. Here, for instance, the Manly Mustache Man summarizes the plot of True Detective, season 1:

What, if some day or night a demon were to steal after you into your loneliest loneliness and say to you: “This life as you now live it and have lived it, you will have to live once more and innumerable times more; and there will be nothing new in it, but every pain and every joy and every thought and sigh and everything unutterably small or great in your life will have to return to you, all in the same succession and sequence — even this spider and this moonlight between the trees, and even this moment and I myself. The eternal hourglass of existence is turned upside down again and again, and you with it, speck of dust!”

Would you not throw yourself down and gnash your teeth and curse the demon who spoke thus? Or have you once experienced a tremendous moment when you would have answered him: “You are a god and never have I heard anything more divine.” If this thought gained possession of you, it would change you as you are or perhaps crush you. The question in each and every thing, “Do you desire this once more and innumerable times more?” would lie upon your actions as the greatest weight. Or how well disposed would you have to become to yourself and to life?

Here again, I don’t blame the average HBO viewer for having their minds blown by this (or at least pretending to), but people with PhDs should damn well know better. This is existentialism for dummies, but since they spent most of their off hours in grad school reading Harry Potter …

Severian, “The One Pop Culture Thing”, Rotten Chestnuts, 2021-09-16.

July 13, 2024

“Canada has disclosure issues”

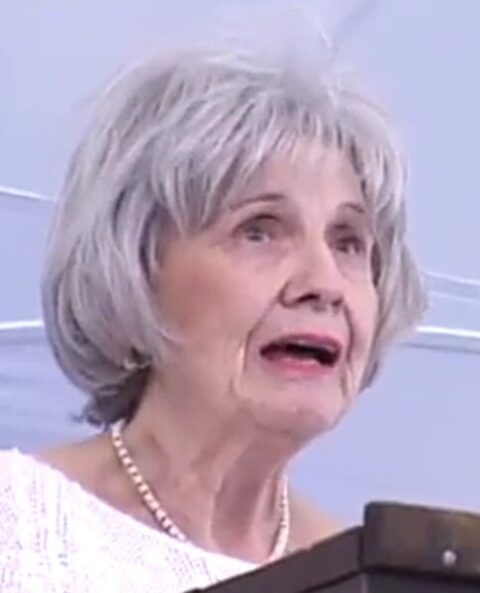

The recent revelations about Nobel Prize winner Alice Munro’s family have certainly roiled the turgid waters of Canada’s tiny literati community, but was the scandal actually all that well hidden beforehand?

Alice Munro accepting the 2006 Edward MacDowell Medal, 13 August 2006.

Screenshot from a video of the event via Wikimedia Commons.

The Toronto Star ran two articles last weekend revealing that Andrea Skinner, third and youngest daughter of Nobel-prize-winning author Alice Munro, was sexually assaulted as a nine-year-old by her stepfather, Gerald Fremlin, Alice’s second husband.

The assaults occurred in the 1970s. Alice learned of them in 1992 when Andrea, then twenty-five, wrote her a letter detailing the abuse. After briefly leaving Fremlin, Alice returned to him. Andrea, feeling her mother had chosen her abuser over her, eventually cut ties with Alice and went to the police. Fremlin was convicted of indecent assault in 2005.

I’m not going to dwell on the abuse. It’s all here, and it’s distressing to read. One can only hope that recognition of what she suffered as a child and the pain she’s carried throughout her life brings some solace to Andrea.

I wish that had been my first reaction to the stories, but I was too long a journalist. My first thought was sordid. Good on the Star for getting the scoop.

My second thought was, how was this not reported earlier? It’s obviously a big story, and it all played out in open court. It’s surprising that it didn’t make headlines.

In yesterday’s Star, the always interesting Stephen Marche put the blame on “a specifically Canadian conspiracy of silence” amounting to “a national pathology”. He recalls that CBC radio star Peter Gzowski’s dirty laundry wasn’t aired until he’d passed; that CBC radio star Jian Ghomeshi’s outrageous behavior was not immediately called out; that author Joseph Boyden and singer Buffy Sainte-Marie both passed as Indigenous for a long time (Boyden does, in fact, have Indigenous blood). “Everybody knew but nobody knew,” Marche writes of each of these cases, adding that the Canadian arts and entertainment community “has been a breeding ground for monsters”.

I think Stephen has a low bar for monstrosity, but I am susceptible to his broader argument. Part of the reason I was happy that the Star got the scoop (and sincere congratulations to editor Deborah Dundas and reporter Betsy Powell on landing it) was that we sometimes first read of our biggest scandals in the international press. Toronto mayor Rob Ford’s crack scandal was revealed by Gawker, Justin Trudeau’s blackface habit by Time. Canada has disclosure issues.

The more I think about those issues, however, the less it seems we’re alone with them. How long did it take Harvey Weinstein’s crimes to make headlines? Bill Cosby’s? The US has had its share of long-running identity hoaxes: Elizabeth Warren, Hilaria Baldwin, Rachel Dolezal, and Jessica Krug. We didn’t learn that Kerouac was a thug and Salinger a creep until after they were gone. And it’s especially hard to sustain Marche’s argument that Canada is an outlier when the White House has been playing Weekend at Bernie’s for the last couple of years.

Certain stories are just slow to break. People keep secrets. Others abet them. Not many journalists frequent courtrooms way out there in Goderich, Ontario, and Fremlin’s name on the docket would not have sent off flares. Most people I’ve spoken to this week couldn’t have named Mr. Alice Munro last week.

There was no conspiracy, or at least not a broad one. I’m confident that any newsroom I was a part of would have run with the Munro story had we caught a whiff of Fremlin’s conviction. It’s not impossible to imagine other newsrooms making different editorial choices, perhaps arguing that Fremlin’s assaults didn’t merit coverage: he was a nobody apart from his association with Alice Munro; the offence was minor in a criminal sense (he served no time); Alice was not a party to the assaults; publishing the story would only serve to smear her by association. But I’ve not seen any evidence that any news outlet had a whiff of this story.

Only a small circle of people knew of Fremlin’s crime, most of them in the Munro family, and they weren’t talking. I contacted a few of the best Canadian literary gossips I know and they had heard nothing until last weekend. It’s not true that “everybody knew”.

Two who did know were Alice’s publisher, Douglas Gibson, and her biographer, Robert Thacker.

April 3, 2024

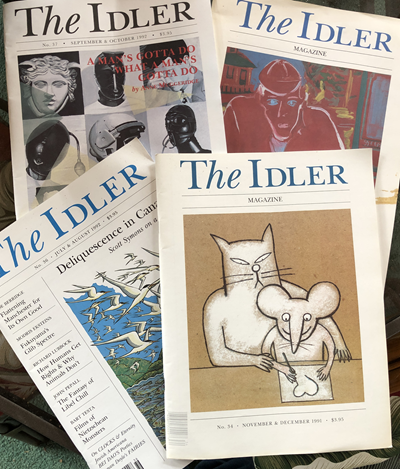

Canada’s The Idler was intended for “a sprightly, octogenarian spinster with a drinking problem, and an ability to conceal it”

David Warren had already shuttered The Idler by the time I met him, but I was an avid reader of the magazine in the late 80s and early 90s. I doubt he remembers meeting me, as I was just one of a cluster of brand-new bloggers at the occasional “VRWC pub nights” in Toronto in the early aughts, but I always felt he was one of our elder statesmen in the Canadian blogosphere. He recalls his time as the prime mover behind The Idler at The Hub:

Some late Idler covers from 1991-92. I’ve got most of the magazine’s run … somewhere. These were the ones I could lay my hands on for a quick photo.

This attitude was clinched by our motto, “For those who read.” Note that it was not for those who can read, for we were in general opposition to literacy crusades, as, instinctively, to every other “good cause”. We once described the ideal Idler reader as “a sprightly, octogenarian spinster with a drinking problem, and an ability to conceal it”.

It was to be a magazine of elevated general interest, as opposed to the despicable tabloids. We — myself and the few co-conspirators — wished to address that tiny minority of Canadians with functioning minds. These co-conspirators included people like Eric McLuhan, Paul Wilson, George Jonas, Ian Hunter, Danielle Crittenden, and artists Paul Barker and Charles Jaffe. David Frum, Andrew Coyne, Douglas Cooper, Patricia Pearson, and Barbara Amiel also graced our pages.

I was the founder and would be the first editor. I felt I had the arrogance needed for the job.

I had spent much of my life outside the country and recently returned to it from Britain and the Far East. I had left Canada when I dropped out of high school because there seemed no chance that a person of untrammelled spirit could earn a living in Canadian publishing or journalism. Canada was, as Frum wrote in an early issue of The Idler, “a country where there is one side to every question”.

But there were several young people, and possibly many, with some literary talent, kicking around in the shadows, who lacked a literary outlet. These could perhaps be co-opted. (Dr. Johnson: “Much can be made of a Scotchman, if he be caught young.”)

The notion of publishing non-Canadians also occurred to me. The idea of not publishing the A.B.C. of official CanLit (it would be invidious to name them) further appealed.

We provided elegant 18th-century design, fine but not precious typography, tastefully dangerous uncaptioned drawings, shrewd editorial judgement, and crisp wit. I hoped this would win friends and influence people over the next century or so.

We would later be described as an “elegant, brilliant and often irritating thing, proudly pretentious and nostalgic, written by philosophers, curmudgeons, pedants, intellectual dandies. … There were articles on philosophical conundrums, on opera, on unjustifiably unknown Eastern European and Chinese poets.”

We struck the pose of 18th-century gentlemen and gentlewomen and used sentences that had subordinate clauses. We reviewed heavy books, devoted long articles to subjects such as birdwatching in Kenya or the anthropic cosmological principle, and we printed mottoes in Latin or German without translating them. This left our natural ideological adversaries scratching their heads.

January 16, 2024

Mark Twain’s Huck Finn

In Quillette, Tim DeRoche re-reads Huck Finn after finally engaging with Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin, and finds the two books are not in opposition but should be read as complementing each other:

Twain scholar Laura Trombley (now the President of Southwestern University in Texas) once told me that Huck Finn isn’t about slavery. “It’s about an abused boy looking for a safe haven,” she said. It was daring for Twain to give a voice to the untutored, unwashed son of the town drunk.

You don’t know about me without you have read a book by the name of “The Adventures of Tom Sawyer”; but that ain’t no matter. That book was made by Mr. Mark Twain, and he told the truth, mainly. There was things which he stretched, but mainly he told the truth. That is nothing. I never seen anybody but lied one time or another …

Huck’s voice, often described as “realistic”, is actually a highly stylized literary device and a brilliant riff on how real boys talk. In these first few sentences, Twain inserts himself into the story and sets his protagonist up to be an unreliable narrator, as Huck admits that there will be “stretchers” of his own along the way.

Huck Finn is our national epic, much like The Odyssey is for Greece or the Nibelungenlied is for Germany. Like those older epics, Huck Finn can be read as version of a Jungian myth, in which the hero descends into the Underworld, undergoes trials and tribulations, and returns to us reborn. This story of two travelers on an epic journey is an archetype of our culture, which is why it is retold with such frequency. It’s possible to read every American road novel or movie as a reworking of Huck Finn.

Twain may not have written in verse, but Huck’s narration is beautiful and lyrical and so distinctively American that it has influenced generations of American writers, both popular and literary. That indelible voice, at once innocent and highly perceptive, is the fixed moral point from which Twain can then satirize so many different segments of his beloved country — preachers, con men, politicians, actors, and ordinary gullible Americans.

The book has been criticized as one of the first “white savior” narratives, but this gets it exactly backwards. Huck doesn’t save anyone in the novel. (One of Jane Smiley’s criticisms, in fact, is that Huck doesn’t “act” to save his friend.) It is actually Jim, the slave, who saves Huck — both literally and figuratively. It is Jim who provides Huck with a safe haven, and it is Jim who calls Huck to account when Huck treats him as less than human: “En all you wuz thinkin ’bout wuz how you could make a fool uv ole Jim wid a lie. Dat truck dah is trash, en trash is what people is dat puts dirt on de head er de fren’s en makes ’em ashamed.”

Huck eventually humbles himself before Jim and tells us, “I didn’t do him no more mean tricks, and I wouldn’t done that one if I’d a knowed it would make him feel that way.” Huck may be the protagonist of this story, but the slave Jim is its moral hero. It is Jim who reveals himself to be a fugitive slave so that Tom Sawyer can get medical attention for his gunshot wound. And after he is freed from slavery, Jim heads home to assume his responsibilities as a husband and father.

In contrast to Jim, Huck yearns for adventure and escape. Forced to live with the Widow Douglas and Miss Watson at the start of the book, he resents their attempts to “sivilize” him. He feels “all cramped up” by the clothes they make him wear, and he dismisses their Biblical teaching because he “don’t take no stock in dead people”. Instead of returning home with Jim, Huck tells us that he intends to “light out for the territory”. He represents one aspect of the American spirit — ironic, secular, individualistic.

January 7, 2024

Evelyn Waugh’s horrible family

In the latest SHuSH newsletter, Ken Whyte explains why Evelyn Waugh drank:

Happy New Year! How were your holidays? Were you as festive as undergraduate Evelyn Waugh kicking off his Christmas break in 1924?

Then I went to Oxford. Drove to 31 St Aldates where I found an enormous orgy in progress. Billy and I unearthed a strap and whipped Tony. Everyone was hideously drunk except, strangely enough, myself. After a quiet day in cinemas, I had a dinner party of Claude, Elmley, Terence, Roger Hollis and a poor drunk called MacGregor. I arrived quite blind after a great number of cocktails at the George with Claude. Eventually the dinner broke up and Claude, Rogers Hollis and I went off for a pub crawl which after sundry indecorous adventures ended up at the Hypocrites where another blind was going on. Poor Mr McGregor turned up after having lain with a woman but almost immediately fell backwards downstairs. I think he was killed. Next day I drank all morning from pub to pub and invited to lunch with me at the New Reform John Sutro, Roger Hollis, Claude and Alfred Duggan. I ate no lunch but drank solidly and was soon in the middle of a bitter quarrel with the President — a preposterous person called Cotts — who expelled me from the club. Alfred and I then drank double brandies until I could not walk. He carried me to Worcester where I fell out of the window then relapsed into unconsciousness punctuated with severe but well directed vomitings. On Wednesday I lunched with Robert Byran at the New Reform and the man Cotts tried to throw me out again. Next day I lunched with Hugh and drank with him all the afternoon and sallied out with him fighting drunk at tea time when we drank at the New Reform till dinner… Next day, feeling deathly ill, I returned to London having spent two months’ wages. I had to dine with Alex, Richard Greene, Julia Strachey … and then back to Richard’s home for a drink. …

[…]

I picked up Alexander Waugh’s Fathers and Sons: The Autobiography of a Family (2004), several weeks ago. I’ve been enjoying it so much that I’m rationing it, reading about ten pages at a time to make it last.

Alexander Waugh is a music writer and biographer, former opera critic at the Evening Standard, son of novelist and Private Eye diarist Auberon Waugh, grandson of the aforementioned Evelyn, the titan of English letters whose brother, Alec, and father, Arthur, were also reasonably famous writers. The book is about the interpersonal relations of these three generations of men who produced about 180 books among them. And it’s wild. These are hugely and incorrigibly flawed people. Often horrible to one another (also to outsiders but they save their best for kin). They are in equal parts perverse and hilarious, and often brilliant, especially Evelyn. I can’t believe people ever behaved this way.

Undergraduates have never required reasons to binge drink, but you can’t read the opening chapters of Fathers and Sons without thinking Evelyn had special motivation. He was the second son of Arthur. His older brother, Alec, was “the firstling”, the “future head of the family”, their parents’ “darling lamb”, and mom and pop didn’t care who knew it, least of all Evelyn.

Arthur and his missus, Kate, had an “unbounded fascination for Alec”, who won all his school honours and was star of the cricket team. Arthur considered the boy a literal gift from God and believed that they could communicate telepathically. He would write him notes like: “I simply go about thinking of your love for me all the time”. Their relationship, writes Alexander, was “hot, clammy and compulsive”, and to the “objective eye their behavior might have resembled a pair of star-crossed teenage lovers”. Indeed, it was romantic in all but the physical sense — Arthur saved his sexual depredations for girls of tender age with whom he played “tickling games” (he also had a fetish involving young women and bicycles).

In addition to being second born, Evelyn made the mistake of being male. His parents had wanted a daughter; they consoled themselves by giving him an effeminate name and dressing him in bonnets and frills long beyond the standard of the day. He was said to be a “warm, bright. sweet-natured and affectionate child”, at least until an awareness of the family dynamic dawned. In Edwardian terms, he was treated as a bastard child by his legitimate parents. His possessions were hand-me-downs. He attended the less expensive school. When eleven-year-old Evelyn asked for a bicycle, his parents bought a bigger and better one for Alec. When Alec asked for a billiard table, space was found for it in Evelyn’s room. Despite winning prizes and becoming head of his house in school, and president of the debating society, and editor of the school magazine, Evelyn remained an afterthought and something of a nuisance in the minds of his Alec-obsessed parents.

Evelyn responded to his circumstances in a clever and self-protective fashion, defining himself against his brother and father. By adolescence, he had an inkling that he was smarter and funnier than both. They could keep their mawkish outpourings of emotion toward one another; he would be hard of head and sharp of tongue. By his early teen years, he was confiding to his diary that Arthur was a fat and “ineffably silly” Victorian sentimentalist. He considered both Alec and Arthur philistines. “Terrible man, my father”, Evelyn said to a schoolmaster. “He likes Kipling.”

To the extent that his parents thought about Evelyn, they were disturbed by his dark moods and lassitude, and intimidated by his cynical wit. Both Alec and Arthur were threatened by Evelyn as a potential literary rival. When Evelyn, in what was becoming a typical act of rebellion, ran up an expensive restaurant tab and had it sent to an outraged Arthur, Alec said: “You know father, if Evelyn turns out to be a genius, you and I might be made to look very foolish by making a fuss over ten pounds, seventeen and ninepence.”

So you can perhaps see how young Evelyn Waugh developed an enthusiasm for drink remarkable even in an undergrad, and why the rare characters killed in gruesome fashion in his fiction tended to be fathers.

October 18, 2023

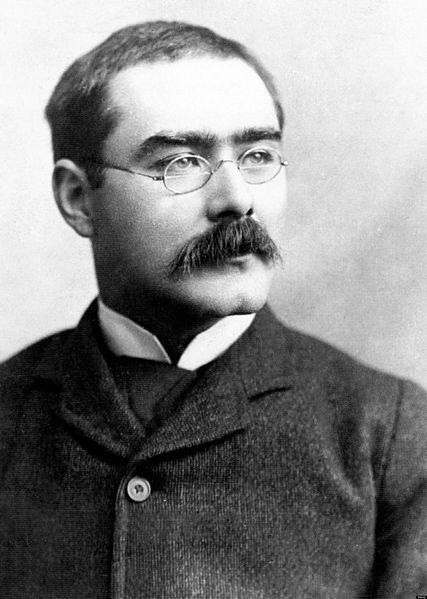

George Orwell’s views on Rudyard Kipling’s worldview

David Friedman comments on Orwell’s essay “Rudyard Kipling“, published a few years after the poet’s death in Horizon, September 1941:

Portrait of Rudyard Kipling from the biography Rudyard Kipling by John Palmer, 1895.

Photo via Wikimedia Commons.

During five literary generations every enlightened person has despised him, and at the end of that time nine-tenths of those enlightened persons are forgotten and Kipling is in some sense still there.

Orwell’s essay on Rudyard Kipling in the Letters and Essays is both more favorable and more perceptive than one would expect of a discussion of Kipling by a British left-wing intellectual c. 1940. Orwell recognizes Kipling’s intelligence and his talent as a writer, pointing out how often people, including people who loath Kipling, use his phrases, sometimes without knowing their source. And Orwell argues, I think correctly, that Kipling not only was not a fascist but was further from a fascist than almost any of Orwell’s contemporaries, left or right, since he believed that there were things that mattered beyond power, that pride comes before a fall, that there is a fundamental mistake in

heathen heart that puts her trust

In reeking tube and iron shard,

All valiant dust that builds on dust,

And guarding, calls not Thee to guard,But while there is a good deal of truth in Orwell’s discussion of Kipling it is mistaken in two different ways, one having to do with Kipling’s view of the world, one with his art.

Orwell writes:

It is no use claiming, for instance, that when Kipling describes a British soldier beating a ‘nigger’ with a cleaning rod in order to get money out of him, he is acting merely as a reporter and does not necessarily approve what he describes. There is not the slightest sign anywhere in Kipling’s work that he disapproves of that kind of conduct — on the contrary, there is a definite strain of sadism in him, over and above the brutality which a writer of that type has to have.

There are passages in Kipling, not “Loot“, the poem Orwell quotes but bits of Stalky and Company, which support the charge of a “strain of sadism”. But the central element which Orwell is misreading is not sadism but realism. Soldiers loot when given the opportunity and there is no point to pretending they don’t. School boys beat each other up. Schoolmasters puff up their own importance by abusing their authority to ridicule the boys they are supposed to be teaching. Life is not fair. And Kipling’s attitude, I think made quite clear in Stalky and Company, is that complaining about it is not only a waste of time but a confession of weakness. You should shut up and deal with it instead.

A more important error in Orwell’s essay is his underestimate of Kipling as an artist, both poet and short story writer. Responding to Elliot’s claim that Kipling wrote verse rather than poetry, Orwell claims that Kipling was actually a good bad poet:

What (Elliot) does not say, and what I think one ought to start by saying in any discussion of Kipling, is that most of Kipling’s verse is so horribly vulgar that it gives one the same sensation as one gets from watching a third-rate music-hall performer recite ‘The Pigtail of Wu Fang Fu’ with the purple limelight on his face, AND yet there is much of it that is capable of giving pleasure to people who know what poetry means. At his worst, and also his most vital, in poems like ‘Gunga Din’ or ‘Danny Deever’, Kipling is almost a shameful pleasure, like the taste for cheap sweets that some people secretly carry into middle life. But even with his best passages one has the same sense of being seduced by something spurious, and yet unquestionably seduced.

I am left with the suspicion that Orwell is basing his opinion almost entirely on Kipling’s best known poems, such as the two he cites here, both written when he was 24. He was a popular writer, hence his best known pieces are those most accessible to a wide range of readers. He did indeed use his very considerable talents to tell stories and to make simple and compelling arguments, but that is not all he did. There is no way to objectively prove that Kipling wrote quite a lot of good poetry and neither Orwell nor Elliot, unfortunately, is still alive to prove it to, but I can at least offer a few examples …

September 7, 2023

J.R.R. Tolkien was completely at odds with the literati of his day

In The Critic, Sebastian Milbank marks the 50th anniversary of the death of J.R.R. Tolkien:

A romantic Edwardian, steeped in Northern European folklore and Victorian literature, Tolkien was and is despised by large parts of the fashionable literary establishment. I have known very few neutral reactions to his work. People either love or loathe Lord of the Rings, which seems doomed to eternally inspire adoration or ire, and nothing much in between.

The often ferocious response of many critics perhaps stemmed from the apparent anachronism of the book, combined with its massive popularity. It was published in 1954, at a time when literary modernism was dominant and pervading the academy. Modernist writers were obsessed with interiority, broke with prior literary convention, and traded in irony, ambiguity and convoluted psychology. Literary critics of the time were taking up the “New Criticism”, which dispensed not only with the previous generation’s fascination with historical context in favour of close reading, but also with the traditionalist concerns for beauty and moral improvement, which were regarded as subjective and emotionally driven. Spare, complex prose, focused on the darker side of society, was in vogue. Into this context dropped 1,200 pages of dwarves, elves and hobbits in a grand battle of good and evil. They were greeted with the sort of enthusiasm one can imagine.

Edmund Wilson called the books “balderdash”, a battle between “Good people and Goblins”. The book’s morality was a sticking point even for the most sympathetic critics, with Edwin Muir lamenting that “his good people are consistently good, his evil figures immovably evil”. As his work travelled into the 60s, political problems cropped up, with one feminist critic writing a book-length attack on the series to denounce it as “irritatingly, blandly, traditionally masculine”.

The mystery of how a book can so sharply divide opinion is answered perhaps by how profoundly original and unusual The Lord of the Rings and Tolkien’s wider legendarium are. They are shamelessly moralistic, written on the basis of exhaustive literary theory, linguistics, geography and world-building, and quite devoid of social commentary or Empsonian irony. Yet they are as much a radical departure from prior literary forms as modernist literature itself is, making the book doubly at odds with prevailing style and doubly original.

The moralism of Tolkien’s work is not, as some critics seem to suppose, the product of schoolboy simplicity. It is far too rigorous for that. So morally charged and orchestrated is the novel, that it would be numbered amongst the small number of works that might have passed Plato’s test for literature. Not only is this in respect of its exacting honouring of good characters and depreciation of wicked ones within its narrative framework, but equally in Tolkien’s utter refusal of allegory, thus meeting Plato’s challenge that poets are dangerous imitators of the world.

June 25, 2023

Fifty years after The Princess Bride was published

William Goldman’s novel The Princess Bride was not a blockbuster, nor did the movie adaptation get a huge box office when it released in 1987. Yet despite apparent early mediocrity, it became a cult classic. It’s now fifty years after the book came out, and Kevin Mims has a look back at both the novel and the movie:

Even by the eccentric standards of fantasy literature, William Goldman’s 1973 novel The Princess Bride is extremely odd. The book purports to be an abridged edition of a classic adventure story written by someone named Simon Morgenstern. In a bizarre introduction (more about which in a moment), Goldman claims merely to have acted as editor. Unlike Rob Reiner’s much-loved 1987 film adaptation, the book’s full title is The Princess Bride: S. Morgenstern’s Classic Tale of True Love and High Adventure, The “Good Parts” Version. Yes, all that text actually appeared on the cover of the book’s first hardcover edition (all but the first three words have been scrubbed from the covers of most subsequent editions).

In the 1990s, I worked at a Tower Books store in Sacramento. Every few months, someone would come into the store and ask if we had an unabridged edition of S. Morgenstern’s The Princess Bride. The first time this happened, a younger colleague who had worked there longer than I had told my customer, “The Princess Bride was written by William Goldman. There is no S. Morgenstern. Goldman made him up.” The customer wasn’t convinced. “It’s metafiction,” my colleague explained. “A novel that comments on its own status as a text.” When the customer had left, my colleague told me that a lot of people still believe there is an original version of the novel available somewhere, written by Morgenstern. Having fallen in love with the story via the Hollywood film, they were now looking for the ur-text.

Although I was a big fan of William Goldman, I had never read The Princess Bride. My wife and I saw the film when it first appeared in American theaters, and we have rewatched it several times since on VHS and DVD. Only about 10 years ago did I actually get around to reading the novel. And when I did, I found myself sympathizing with all those people who still believe that, somewhere in the world, there exists an unedited edition.

In his introduction, Goldman tells us that S. Morgenstern was from the tiny European nation of Florin, located somewhere between Germany and Sweden, which is where the story’s action takes place. Such a place never existed, but it’s not surprising that many 21st-century American readers don’t know the names of every current and former European kingdom. European history is littered with microstates that rose briefly and then vanished without leaving much of a trace. Back in the 1990s, before Internet access became commonplace, confirming the existence of a small defunct European statelet would have involved a trip to the library.

But readers in the 1970s might have been more alive to Goldman’s ruse. Back then, metafiction was all the rage. John Barth became a literary superstar (among the academic set, anyway) with books like The Sot-Weed Factor (which, like The Princess Bride, is a fantastical comic adventure supposedly written by a fictional author) and Giles Goat-Boy (the text of which, Barth writes in the foreword, was said to have been written by a computer). In 1983, Goldman would publish a second novel behind the Morgenstern pseudonym, titled The Silent Gondoliers, but this time he removed all mention of himself, even from the copyright page.

May 15, 2023

QotD: How military history shapes cultures and societies

… war and conflict deeply shaped societies in the past and to the degree that we think that understanding those societies is important (a point on which, presumably, all historians may agree), it is also important to understand their conflicts. I am often puzzled by scholars who work on bodies of literature written almost entirely by combat veterans (which is a good chunk of the Greek and Latin source tradition), in societies where most free adult men probably had some experience of combat, who then studiously avoid ever studying or learning very much about that combat experience (that “war and society” lens there again). Famously, Aeschylus, the greatest Greek playwright of his generation, left no record of his achievements in writing in his epitaph. Instead he was commemorated this way:

Aeschylus, son of Euphorion, the Athenian lies beneath this marker

having perished in wheat-bearing Gela

Of his well-known prowess, the grove of Marathon can speak

And long-haired Mede knows it well.If a scholar wants to understand Aeschylus or his plays, don’t they also need to understand this side of his experience too? I know quite a number of scholars who ended up coming to military history this way, looking to answer questions that were not narrowly military, but which ended up touching on war and conflict. For that kind of research – for our potential scholar of Aeschylus – it is important that there be specialists working to understand war and conflict in the period. Of course this is particularly true in understanding historical politics and political narratives, given that most pre-modern states were primarily engines for the raising of revenues for the waging of war (with religious expenditures typically being the only ones comparable in scale).

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Why Military History?”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2020-11-13.

April 28, 2023

Legends Summarized: Journey To The West (Part X)

Overly Sarcastic Productions

Published 30 Dec 2022Journey to the West Kai, episode 7: Double Trouble

(more…)

March 24, 2023

QotD: The academic specializations of the Great Library

[Carl] Sagan’s roll call of Greek scientists who he claims worked at the Great Library makes it sound like some kind of ancient Mediterranean MIT: Eratosthenes, Hipparchus, Euclid, Dionysius of Thrace, Herophilos, Archimedes, Ptolemy and so on. Unfortunately, only one of these people – Eratosthenes – can definitely be said to be associated with the Great Library. Two others from Sagan’s list – Dionysius and Ptolemy – may have been. And once you take out all the others, that really leaves only Eratosthenes and (maybe) Conon of Samos and, much later, Ptolemy as scholars of the Great Library who did anything like what we would call “science”. We can perhaps shoehorn in Euclid and the physicians and anatomists Herophilos and Erasistratos, depending on when the Mouseion was established, but overall the evidence for the institution as some great centre of scientific research is actually rather thin.

Which means it is perhaps less surprising to learn, on examining the sources, that the Great Library was actually celebrated mainly for a specialisation which is about as far from modern science as possible: the study of poetry. This makes some sense, given that the Mouseion was dedicated to the Muses, four of whom represented forms of verse. The works of Homer, in particular, were a primary focus of study across the Greek world and his poems permeated thought, writing and everyday speech rather like the works of Shakespeare and the texts of the Bible do today. It was the scholars of the Mouseion who, on gathering and comparing copies of the Illiad and Odyssey from across the Greek-speaking world, noticed textual differences large and small and established the kind of textual analysis still used by editors to this day; working to determine the best possible text from the manuscript variants. Other works of Greek poetry, such as the odes of Pindar, were also analysed and studied in a similar way, as were the works of the great Athenian playwrights.

The importance of literary studies at the Mouseion can be seen by analysing the specialisations of the men we know were directors of the institution and therefore “librarians” of the Great Library. […] of these scholars, only Eratosthenes is known for doing anything that we would consider “science”, the others were devoted to literary and textual analysis, poetry and grammar. Of course, these scholars were polymaths and most of them would probably have ranged over many topics including areas of mathematics and natural philosophy; Eratosthenes himself was nicknamed “Beta” because he covered so many disciplines he was something of a jack of all trades and master of none, so his colleagues mocked him as “Number 2” in all subjects. That aside, the idea that the Mouseion was a major centre of scientific speculation is at best an exaggeration and largely yet another fantasy.

Tim O’Neill, “The Great Myths 5: The Destruction Of The Great Library Of Alexandria”, History for Atheists, 2017-07-02.

October 3, 2022

QotD: The foundation of Rome, as recounted by Vergil and Livy

Both Vergil and Livy begin by putting down Homeric roots and anchoring their stories in the Trojan War. That makes a good deal of sense from a mythic perspective: the Iliad and the Odyssey were the most illustrious legends of the Hellenic world and so it made sense for the Romans, looking to claim a place in the Mediterranean, to make that claim through connection to this most illustrious of tales (and of course later, when Rome was a colossus astride the Mediterranean, which the Romans by then called mare nostrum, “our sea”, it made sense they would prefer a heroic origin with grandeur to match their power at the time). And so both Vergil and Livy begin their story with Aeneas and his plucky band of Trojan refugees, fleeing the fall of Troy (though interesting, while Vergil tells the tale as a harrowing escape, Livy politely suggests that perhaps Homer’s Achaeans let Aeneas go, Liv. 1.1).

Aeneas (son of Aphrodite/Venus and a mortal man, Anchises) does appear, by the by, in the Iliad, though he isn’t a particularly notable or impressive hero (naturally Vergil will embroider Aeneas until he is presented as the equal of an Achilles or Odysseus because … well, wouldn’t you?). The Aeneid follows (with the aid of a major flashback) Aeneas as he shepherds his surviving Trojans from Troy to their prophesied new homeland in Italy (with a minor stopover in Carthage) and then covers also the war that breaks out between Aeneas’ Trojans and the local inhabitants (the Latins) when he arrives. Vergil cuts off at the climactic moment of the war (which in turn presents Aeneas as rather morally grey, a feature that is also present, as we’ll see, in Livy’s retelling of Rome’s legends), but Livy provides the denouement. After a period of conflict (Livy presents two different versions of the exact sequence), Aeneas ends up married to Lavinia, the daughter of Latinus, king of the Latins (Livy calls them the Aborigines – lit, “the native inhabitants”, Vergil the Latins; in both cases Latinus is their king) and the Trojan exiles and Latinus’ people form a single community at Lavinium, which in turn founds a colony at Alba Longa, both in Latium (the region of Italy in which Rome is, although note we haven’t founded Rome yet).

We then fast forward a few generations. Rhea Silvia, a priestess of Vesta at Alba Longa gives birth to twins, Romulus and Remus by (Livy expresses some doubt) the god Mars. The twins are exposed (for complicated royal-family-drama reasons we needn’t get into) and rescued by either a she-wolf or a woman of ill-repute (Livy isn’t sure which on account of Latin lupa having both meanings and clearly both legends existed, Liv. 1.4) and raised among shepherds in the hills of northern Latium. More politics ensues, Romulus and Remus, having grown to adulthood, right some wrongs in their home city of Alba Longa and set out to found their own city.

At which point Romulus promptly gets into a fight with and murders Remus over who is going to be in charge (this sort of intense moral ambiguity where the venerated legendary founder figures are also quick to violence and deeply flawed is also a feature of the Aeneid and can be read either as a commentary on Augustus or as some lingering Roman discomfort with their own recent history of civil wars running from 88 to 31 BC; we are not the first people in history to have very mixed feelings about how well people in our country’s past lived up to our ideals). Crucially, Romulus forms his new settlement (prior to the fratricide) out of – as Livy has it – “the excess multitudes of the Albans and Latins, to which were added the shepherds” (Liv. 1.6.3). After this, desiring to increase the population of the city, Romulus sets a place of refuge in the city so that “a crowd of people from neighboring places, altogether without distinction, free and slave, fled there eager for new things” (Liv. 1.8.6) and were incorporated into Romulus’ growing city. Livy approves of this, by the by, declaring it the first step towards rising greatness.

Romulus quickly has another problem because all of these new settlers were men, so he concocts a plot to carry off all of the unmarried women of the neighboring people, the Sabines – an Umbrian people (we’ll come back to this, for now we’ll note they are ethnically and linguistically distinct from the Latins) – who lived in the hills north of Rome under the guise of a religious ceremony (Liv. 1.9-13). At a festival where the Sabines had been lured to under false pretenses, the Romans abduct and forcibly marry the Sabine women, while using hidden weapons to chase away their families (I should note Livy goes to some length to assure the reader that the captured maidens were subsequently persuaded to marry their Roman captors, rather than forced (Liv. 1.9.14-16), though what choice he imagines the unarmed, captive women to have had is left for the reader to wonder at in vain; in any event, we need not share Livy’s judgement or his effort at patriotic euphemism and may simply note that bride-capture is a form of rape). The Sabines naturally go to war over this but (according to Livy) a peace is mediated by the captured women (according to Livy, unwilling to see their new husbands and old fathers kill each other) and the two communities instead merge on equal terms. In the midst of all of this, Livy does have Romulus set down a set of common customs for his people, which he thinks to have been mostly Etruscan (Liv. 1.8.3), the Etruscans being the people inhabiting Etruria (modern Tuscany) the region directly north of Rome (Rome sits, in essence, on the dividing line between Latium to the South and Etruria to the North).

Now we want to note two things here from this high-speed trip through the first few chapters of Livy. First is the deep ambivalence towards Roman violence here. Livy presents Rome as a city founded on fratricide, conquest, rape and sacrilege. Livy occasionally attempts to soften the impact of these legends (particular with the Sabines), but only so far. This isn’t really the place to unpack of all of that but suffice to say that I think that Livy’s willingness to open his history of Rome – practically an official history of Rome – so darkly speaks to a literary project still attempting to come to grips with the stunning civil violence which had gripped Rome for Livy’s entire adult life and had, as he wrote, only recently ended. And one day we also ought to come back and do a deeper look at how women function in Livy’s legends and histories (Livy’s account becomes much more properly historical as he gets closer to his own time); women, mostly Roman women, suffering (often sexual) violence so that in their sacrifice the Roman state might be enhanced is a repeated motif in Livy (e.g. Lucretia, Verginia).

But more directly to our topic today, I want to note at this point exactly the sort of society Livy is imagining the earliest Rome, under its first king Romulus, in particular that it consists of a lot of different peoples and heritages. We’ll come back to exactly who all of these peoples are (historically speaking) in a moment. But Livy and Vergil first create a Trojan-Latin fusion community, which produces both Romulus and Remus and their initial core of settlers (mixed in with other, apparently purely Latin communities), who then gather up shepherds from all around, and then invite literally anyone from nearby communities to join them (which must include Etruscan communities to the north as well as Umbrians and Falisci of various sorts from the hills) and then finally fuses that community with the Sabines (an Umbrian people).

So we have our very first Romans, as the first Senate is being set up (1.8.7) and the very first spolia opima – the prize for when one commander defeats his opposite number in single combat – being won (1.10.7) and the very first temple being founded in the city (1.10.7). And those very first Romans, as Livy imagines them, are not autochthonous (that is, the original inhabitants of the place they live), nor ethnically homogeneous, but rather a Trojan-Aborigines-Latin-Faliscian-Umbrian-Etruscan-Sabine fusion community. For Livy, diversity – ethnic, linguistic, religious – defines Rome, from its very first days.

But of course this is all legends – important for understanding how the Romans viewed themselves, but necessarily less valuable for understanding the actual conditions in Rome at its earliest. Unfortunately, we lack reliable written sources for this part of the world so early (most of the “regal” period, when Rome was ruled by kings, notionally from 753 – the legendary founding date for the city – to 509, is beyond historical reconstruction).

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: The Queen’s Latin or Who Were the Romans? Part I: Beginnings and Legends”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2021-06-11.

September 12, 2022

QotD: On the nature of our evidence of the ancient world

As folks are generally aware, the amount of historical evidence available to historians decreases the further back you go in history. This has a real impact on how historians are trained; my go-to metaphor in explaining this to students is that a historian of the modern world has to learn how to sip from a firehose of evidence, while the historian of the ancient world must learn how to find water in the desert. That decline in the amount of evidence as one goes backwards in history is not even or uniform; it is distorted by accidents of preservation, particularly of written records. In a real sense, we often mark the beginning of “history” (as compared to pre-history) with the invention or arrival of writing in an area, and this is no accident.

So let’s take a look at the sort of sources an ancient historian has to work with and what their limits are and what that means for what it is possible to know and what must be merely guessed.

The most important body of sources are what we term literary sources, which is to say long-form written texts. While rarely these sorts of texts survive on tablets or preserved papyrus, for most of the ancient world these texts survive because they were laboriously copied over the centuries. As an aside, it is common for students to fault this or that later society (mostly medieval Europe) for failing to copy this or that work, but given the vast labor and expense of copying and preserving ancient literature, it is better to be glad that we have any of it at all (as we’ll see, the evidence situation for societies that did not benefit from such copying and preservation is much worse!).

The big problem with literary evidence is that for the most part, for most ancient societies, it represents a closed corpus: we have about as much of it as we ever will. And what we have isn’t much. The entire corpus of Greek and Latin literature fits in just 523 small volumes. You may find various pictures of libraries and even individuals showing off, for instance, their complete set of Loebs on just a few bookshelves, which represents nearly the entire corpus of ancient Greek and Latin literature (including facing English translation!). While every so often a new papyrus find might add a couple of fragments or very rarely a significant chunk to this corpus, such additions are very rare. The last really full work (although it has gaps) to be added to the canon was Aristotle’s Athenaion Politeia (“Constitution of the Athenians”) discovered on papyrus in 1879 (other smaller but still important finds, like fragments of Sappho, have turned up as recently as the last decade, but these are often very short fragments).

In practice that means that, if you have a research question, the literary corpus is what it is. You are not likely to benefit from a new fragment or other text “turning up” to help you. The tricky thing is, for a lot of research questions, it is in essence literary evidence or bust. […] for a lot of the things people want to know, our other forms of evidence just aren’t very good at filling in the gaps. Most information about discrete events – battles, wars, individual biographies – are (with some exceptions) literary-or-bust. Likewise, charting complex political systems generally requires literary evidence, as does understanding the philosophy or social values of past societies.

Now in a lot of cases, these are topics where, if you have literary evidence, then you can supplement that evidence with other forms […], but if you do not have the literary evidence, the other kinds of evidence often become difficult or impossible to interpret. And since we’re not getting new texts generally, if it isn’t there, it isn’t there. This is why I keep stressing in posts how difficult it can be to talk about topics that our (mostly elite male) authors didn’t care about; if they didn’t write it down, for the most part, we don’t have it.

Bret Devereaux, “Fireside Friday: March 26, 2021 (On the Nature of Ancient Evidence”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2021-03-26.