At a practical level, as a professor who regularly teaches East Asian philosophies, I die a little inside every time we experience a cultural phenomenon with a veneer of “wisdom from the East” on it. Having imbibed pop culture’s mystical Orient, students will arrive to my classes craving a deeper initiation into Eastern mysteries. Teaching these seekers of wisdom then becomes deflationary.

I was once at an art fair where there was a booth selling temporary tattoos. One of the tattoos was a Chinese character that was translated on the tattoo’s plastic label as “bitch”, an appealing bit of body art for the tough girls among us, I suppose. Except a far more straightforward and accurate translation of the character would be “prostitute”, or maybe “whore”.

Teaching students who fell in love with “Eastern philosophy” via our culture’s myriad Mr Miyagis is like being the one to tell someone her tattoo says “whore”. The tattooed will be better off knowing, but she won’t thank you for telling her. Pop-culture-induced orientalism usually does wash off, but the cleanup is far less alluring than wearing the myth. At least, I console myself, Kondo’s target market is the middle-aged, so maybe my young college students won’t show up with this particular “tattoo”.

Amy Olberding, “Tidying up is not joyful but another misuse of Eastern ideas”, Aeon, 2019-02-18.

April 9, 2022

QotD: Temporary tattoos and cultural literacy

April 5, 2022

QotD: The “rules” of bad writing

Another common habit of the bad writer is to use five paragraphs when one paragraph will do the trick. One of the first rules they used to teach children about writing is the rule of women’s swimsuits. Good writing is like a woman’s swimsuit, in that it is big enough to cover the important parts, but small enough to make things interesting. This is a rule that applies to all writing and one bad writers tend to violate. They will belabor a point with unnecessary examples or unnecessary explication.

Bad writers are also prone to logical fallacies and misnomers. There’s really no excuse for this, as there are lists of common logical fallacies and, of course, searchable on-line dictionaries in every language. In casual writing, like blogging or internet commentary, this is tolerable. When it shows up in a professional publication, it suggest the writer and the editor are not good at their jobs. A brilliantly worded comparison between two unrelated things is still a false comparison. It suggests dishonesty on the part of the writer.

Certain words seem to be popular with bad writers. The word “dialectic” has become an acid test for sloppy reasoning and bad writing. The word “elide” is another one that is popular with bad writers for some reason. “Epistemology” is another example, popular with the legacy conservative writers. Bad writers seem to think cool sounding words or complex grammar will make their ideas cleverer. Orwell’s second rule is “Never use a long word where a short one will do.” It’s commonly abused by bad writers.

Finally, another common feature of bad writing is the disconnect between the seriousness of subject and how the writer approaches the subject. Bad writers, like Jonah Goldberg, write about serious topics, using pop culture references and vaudeville jokes. On the other hand, feminists write about petty nonsense as if the fate of the world hinges on their opinion. The tone should always match the subject. Bad writers never respect the subject they are addressing or their reader’s interest in the subject.

The Z Man, “How To Be A Bad Writer”, The Z Blog, 2019-03-03.

March 19, 2022

QotD: The sterility of partisan political argument

For the partisan of deadly nonsense, the person on the other side is neither right nor wrong, since rightness and wrongness are never to be discussed: the person on the other side is merely a jackass, a bigot, ignorant, uninformed, pathetically stupid, Neanderthal, reactionary, bitter, a yokel, a class-traitor, and racist, racist, racist, and racist.

If you are arguing with someone, say, who has a better education than you, a higher I.Q., with perhaps a doctorate in law and a career as a journalist and a published series of books on his resume, that does not matter. The mere fact that he comes to different conclusions than the Party line indicates that he is stupid uneducated Nazi bigot, and a stupid bigoted fascist racist moron.

This is argumentum ad cloaca —— ratiocination via offal. Whatever the loudest donkey laughs loudest at, you take to be untrue. Since that was the way (admit it!) you yourself were convinced, O ye of little mind, it is the first, usually the only means, to which you resort to convince others: the volume and clamor is what matters, not the content.

The reason for the inadequacy of these condemnations, the reason why they are so unimaginative, is because of the paucity of the moral vocabulary of the Left. They do not have words to express outrage, so they sneer and yodel. They are like creature struck dumb, and only able to act out their condemnation by means of antic pantomime.

The more closely they follow Marx, the more impoverished their moral vocabulary becomes. You cannot call someone evil once you accept the proposition that all standards of good and evil are merely genetically-determined group survival behaviors, or merely culturally determined artifacts, or merely ideological superstructures meant to promote class interests. Your concept has lost its referents: it can be used only metaphorically, or ironically.

Likewise, you cannot call someone damned if you don’t believe in damnation. There is no such thing as blasphemy if there is nothing sacred, supernatural, or divine.

Likewise again, you cannot call someone illogical if logic is no longer the standard used to separate self-consistent from self-contradictory statements: because then you would have to argue the merits of the case, and rely on reason, like Adam Smith, rather than on verbal fetishes, like Karl Marx.

Our Progressive detractors have to call the object of their scorn a racist (or a parallel word, such as sexist, lookist, homophobe, capitalist, colorist, agist, whateverist) because that is the only arrow in their quiver. That is the only thing they have to shoot, so they shoot, and do not care how short of the target the dart falls.

John C. Wright, “The Crazy Years and their Empty Moral Vocabulary”, John C. Wright, 2019-02-18.

March 16, 2022

Etruscan Cities and Civilization

Thersites the Historian

Published 9 Apr 2020The Etruscans were one of the most interesting civilizations of antiquity. In this video, I explore some of the distinctive features of Etruscan civilization and also look at some of the key urban sites in Etruria.

Patreon link: https://www.patreon.com/thersites

PayPal link: paypal.me/thersites

Twitter link: https://twitter.com/ThersitesAthens

Minds.com link: https://www.minds.com/ThersitestheHis…

Steemit/dtube link: https://steemit.com/@thersites/feed

BitChute: https://www.bitchute.com/channel/jbyg…

January 28, 2022

Spartan glossary

As part of a multi-post series at A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry on explaining (and debunking) the modern day mythology of classic-era Sparta, Bret Devereaux compiled a useful glossary of terms that will be of use as I’ll be excerpting several sections of his series for today’s and several future QotD entries. I’ve added a few entries that seem necessary and expanded some others, but these are enclosed in square brackets “[ ]” to show they’re not directly from Bret’s original post.

Acclamation. A vote held by acclamation (sometimes called a “voice vote”) is a vote where, instead of getting an exact count of yes and no votes, the outcome is judged by the volume of people calling out yes or no. Obviously it would be very hard to tell who had really won a close vote. This is used in modern democracies only for very lopsided (typically unanimous) votes; in Classical Sparta, this was the only voting system, votes were never counted.

[Agoge. The Spartan education system for boys (ἀγωγή, pronounced ah-go-GAY). “Spartan boys were, at age seven, removed from their families and grouped into herds (agelai) under the supervision of a single adult male Spartan – except for the heirs to the two hereditary kings, who were exempt. Order was kept by allowing the older boys to beat and whip the younger boys (Xen. Lac. 2.2). The boys were intentionally underfed (Plut. Lyc. 17.4; Xen. Lac. 2.5-6). They were thus encouraged to steal in order to make up the difference, but severely beaten if caught (Plut. Lyc. 17.3-4; Xen. Lac. 2.6-9). … We are not told, but it seems unavoidable that in a system that intentionally under-feeds groups of boys to force them to steal, that the weakest and smallest boys will end up in a failure spiral where the lack of food leads to further weakness and further victimization at the hands of other boys. I should note that while ancient parenting and schooling was certainly more violent than what we do now – the Spartan system was recognized as abnormally violent towards these boys, even by the standards of the time.”]

Apella. The Apella was the popular assembly of Sparta, consisting of all adult male Spartiates over the age of thirty. The Apella was presided over by the Ephors and all votes were by acclamation. The Apella did not engage in debate, but could only vote “yes” or “no”. The Gerousia had the power to ignore the decisions of the Apella. [In most other Greek poleis the equivalent body would be called the ekklesia.]

Ephor. The Ephors were a board of five officials in Sparta, elected annually by the Apella (technically plus the two kings). The Ephors oversaw the two hereditary Spartan kings and could even bring a king up on charges before the Gerousia. In practice, the Ephors – not the kings – wielded the most political power in Sparta. The Ephors were also responsible for ritually declaring war on the helots every year. The institution as a whole is sometimes collectively referred to as the Ephorate.

Gerousia. The Gerousia – literally a council of old men (the members were “Gerontes” – literally “old men”) which consisted of thirty members, 28 elected (by acclamation in the Apella) plus the two hereditary kings. The elected members all had to be over the age of 60. Gerontes were elected for life. The Gerousia decided what motions could be voted on by the Apella and had the power to cancel any decision of the Apella. It also functioned as a court, with the power to try Spartiates and even the kings. In practice, with the Ephors, the Gerousia wielded the real political power in Sparta.

Helot. The subjugated slave class of Sparta, which made up the overwhelming majority of its residents, the Helots did the agricultural labor which kept the Spartan state running. Helots can be further subdivided into the Laconian helots (those living in Sparta proper) and the Messenian helots (the populace of Messenia which had been reduced to helotry after being conquered by Sparta in the 7th century B.C.). Helots often fought in Sparta’s armies, apparently as screening light-infantry forces (and also as camp followers and servants).

Homoioi. See: Spartiates.

Hoplite. Hoplites were Greek heavy infantry soldiers who fought with a heavy round shield (sometimes called a “hoplon” but more correctly an “aspis“) and a spear, typically in armor.

Hypomeiones. One of several sub-citizen underclasses in Sparta, the Hypomeiones (literally “the inferiors”) were former Spartiates who had fallen off the bottom of the Spartan social system, either through cowardice or (more likely) being unable to pay the contribution to the Syssitia. Though free, they had no role in government.

[Kings. Sparta had two royal lines and two kings at all times. The kings were drawn from the Agaids and the Eurypontid families. In theory, both kings had the same set of powers. The kings’ wealth was derived from lands allocated from territory taken from the perioikoi, and the eldest son of the current king in each line was the presumptive heir. On this basis, the kings were almost always the two wealthiest men in Sparta.]

[Kleroi (sing. kleros). The (theoretically) equal plots of land allocated to each Spartiate, worked on his behalf by Helots to generate the contributions to the individual Spartiate‘s Syssitia. Up to half of the production of the kleros had to be paid to the Spartiate by the Helots who worked that land. At some point, the kleroi became inheritable property, which facilitated the accumulation of wealth in fewer and fewer hands, contributing to the demographic collapse of the Spartiate class.]

Lycurgus. [The name of the (almost certainly) mythical founder figure of Sparta.] Lycurgus had been the younger brother of one of Sparta’s two kings, but had left Sparta to travel when his brother died, so that he would be no threat to his young nephew. After a time, the Spartans begged Lycurgus to come back and reorganize society, and Lycurgus – with the blessing of the Oracle at Delphi – radically remade Spartan society into the form it would have for the next 400 years. He did not merely change the government, but legislated every facet of life, from child-rearing to marriage, to the structure of households, the economic structure, everything. Once he had accomplished that, Lycurgus went back to Delphi, but before he left he made all the Spartans promise not to change his laws until he returned. Once the Oracle told him his laws were good, he committed suicide, so that he would never return to Sparta, thus preventing his laws from ever being over turned. So the Spartans never changed Lycurgus’ laws, which had been declared perfect by Apollo himself. Subsequently, the Spartans accorded Lycurgus divine honors, and within Sparta he was worshiped as a god.

Mothax. One of several sub-citizen underclasses in Sparta, the Mothakes were non-citizen men, generally thought to have been the children of Spartiate fathers and helot mothers, brought up alongside their full-citizen half-siblings. Mothakes fought in the Spartan army alongside spartiates, but had no role in government. A surprising number of innovative Spartan commanders – Gylippus and Lysander in particular – came from this class.

Neodamodes. One of several sub-citizen underclasses in Sparta, the Neodamodes were freed helots, granted disputed land on the border with Elis. Though they served in the Spartan army, the Neodamodes lacked any role in government. We might consider the helots who served in Brasidas’ army, the Brasideioi as a type of the Neodamodes (they did settle in the same place).

Peers: See: Spartiates.

Perioikoi (sing. Perioikos). The perioikoi (literally the “dwellers around”) were one of several sub-citizen underclasses in Sparta. The perioikoi were residents of communities which were subjected to the Spartan state, but not reduced to helotry. They lived in their own settlements under the control of the Spartan state, but with limited internal autonomy. The perioikoi seem to have included Sparta’s artisans, producing weapons, armor and tools; they were also made to fight in Sparta’s armies as hoplites.

Polis (pl. poleis). A complicated and effectively untranslatable term, polis most nearly means “community” and is often translated as “city-state”. However, there were poleis in Greece without cities (Sparta being one – a fact often concealed by translators rendering polis as city). Instead a polis consists of a body of citizens, their state, and the territory it controls (including smaller villages but not other subjugated poleis), usually but not always centered on a single urban center. Poleis are almost by definition independent and self-governing (that is, they have eleutheria and autonomia).

Skiritai. The Skiritai were one of several sub-citizen underclasses in Sparta. Dwellers in Skiritis, the mountains between Laconia and Arcadia, they were mostly rural people who were free, but subject to the Spartan state, similar to the perioikoi. The main difference between the two was that the Skiritai – perhaps because of their mountainous homes – served not as hoplites, but as an elite corps of light infantry in the Spartan army.

Spartiates, also called peers or homoioi. The citizen class at Sparta, the Spartiates were a closed ethnic aristocracy. Membership required both a Spartiate father and a Spartiate mother, as well as successful completion of the Agoge and membership in a Syssitia. Spartiate males over thirty were the only individuals in Sparta who could participate in government, although the political power of the average Spartiate was extremely limited.

Syssitia (sing. syssition). The Syssitia were the common mess-groups into which all adult Spartiates were divided. Each member of the Syssitia contributed a portion of the mess-group’s food; the contribution was a condition of citizenship. Spartiates who could not make the contribution lost citizenship and became Hypomeiones.

January 1, 2022

QotD: Heinlein’s “Crazy Years”, Alfred Korzybski’s General Semantics, and modern times

While Heinlein (as far as I know) supplied no rationale for the advent and the recession of the craziness in the Crazy Years, A.E. van Vogt was freer with his speculations: insanity, either of individuals or of peoples, in van Vogt’s stories (and perhaps in the theories of Alfred Korzybski, who discovered or invented General Semantics) is caused by a fracture or disjunction between symbol and object. When your thoughts, and the thing about which you think, do not match up on a cognitive level, that is a falsehood, a false belief. When the emotions associated with the thought do not match to the thing about which you think, that is a false-to-facts association, which can range from merely a mistake to neurosis to psychosis, depending on the severity of the disjunction. You are crazy. If you hate your sister because she reminds you of your mother who beat you, that association is false-to-facts, neurotic. If you hate your sister because you have hallucinated that you are Cinderella, that association is falser-to-facts, more removed from reality, possibly psychotic.

The great and dire events of the early Twentieth Century no doubt confirmed Korzybski in the rightness of this theory. Nothing prevents a race of people from contracting and fomenting a false-to-facts belief: the fantasies of the Nazi Germans, pseudo-biology and pseudo-economics combined with the romance of neo-paganism, stirred the psyche of the German people for quite understandable reasons. From the point of view of General Semantics, the Germans had divorced their symbols from reality, they mistook metaphors for truth, and their emotions adapted to and reinforced the prevailing narrative. They told themselves stories about Wotan and the Blood, about being betrayed during the Great War, about needing room to live, about the wickedness of Jewish bankers and shopkeepers, about the origin of the wealth of nations — and they went crazy.

The Russians, earlier, and for equally psychological and psychopathic reasons told themselves a more coherent but more unreal story about history and destiny, taken from a Millenarian cultist named Marx, and they were, on an emotional level even if not on a cognitive level, convinced that shedding the blood of millions would bring about wealth as if from nowhere. And, because they used the word “scientific” to describe their brand of socialism, they actually thought their play-pretend neurotic story was a scientific theory that had been discovered by rigorous ratiocination — and they went crazy.

Berlin was bombed into submission during the Second World War, and the Berlin Wall collapsed along with the Soviet Empire at the end of the Cold War. But the modern methods of erecting false-to-facts dramas appealing to mass psychology, once discovered, did not fall when their practitioners fell: scientific socialism, naziism, fascism, communism, all have in common the subordination of word-association to political will. All these doctrines have a common ancestor, which is the social engineering theory of language: if you change the connotation of word, so the theory runs, you change the connotations of thoughts. General Semantics says that if an individual, or whole people en mass, adopt deliberately false beliefs, supported by deliberately manipulative word-uses, he or they will have increasingly unrealistic and maladaptive behaviors. Introduce Political Correctness, ignore factual correctness, and the people will go crazy.

The main sign of when madness has possessed a crowd, or a civilization, is when the people are fearful of imaginary or trivial dangers but nonchalant about real and deep dangers. When that happens, there is gradual deterioration of mores, orientation, and social institutions — the Crazy Years have arrived.

John C. Wright, “The Crazy Years and their Empty Moral Vocabulary”, John C. Wright, 2019-02-18.

December 16, 2021

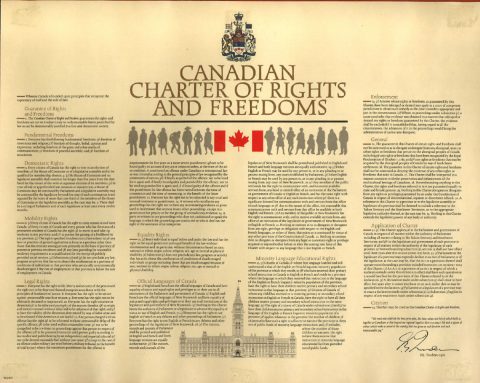

The Charter of Rights and Freedoms versus Quebec’s Bill 21 (Loi sur la laïcité de l’État)

Andrew Potter characterizes our next big constitutional bun-fight as an exploded time-bomb in the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms:

In 1982, Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau and the provincial premiers inserted a time bomb into the Canadian constitution. It finally went off last week, when an elementary school teacher in West Quebec was removed from the classroom for wearing a hijab, in violation of Bill 21, the province’s secularism law.

The case has generated no shortage of outraged commentary in Canada and abroad, with many denouncing what they see as the “bigotry” of the Quebec law. In The Line on Tuesday, Ken Boessenkool and Jamie Carroll argued that far from implementing a secular state, Quebec has simply imposed a state religion that takes precedence over private belief. In response to these criticisms, many Quebecers say that this is just another round of Quebec bashing. The rest of Canada needs to recognize that the province is different, and to mind its own business.

But it is important to realize that something like this was going to happen sooner or later. The patriation of the constitution and the adoption of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms in 1982 seriously destabilized the Canadian constitutional order, and the twin efforts of the Meech Lake and Charlottetown accords to fix that instability only made things worse. But the real ticking bomb here is s.33 of the Charter, a.k.a. the notwithstanding clause, which allows legislatures to override certain sections of the Charter for renewable five-year terms.

The basic tension is between two more or less incompatible views of the country. On the one hand there is the original concept of a federal Canada, where citizens’ political identities are shaped by and through their relationship with their provincial, and to a lesser extent, national, governments. On the other hand, the Charter created a newer understanding of Canadians as individual rights bearers with political and social identities prior to the state, underwritten by the Charter itself.

November 1, 2021

QotD: Latin

Any English speaker who calls Latin easy is either a genius or a fool. It is a synthetic Indo-European language that communicates in ways very different from English. Nouns are divided into at least five classes, each of which has five or six or seven cases – singular and plural – to express meanings that we express by adding prepositions. Pronouns have their own declensions. Except for the perfect passive tenses, verbs are generally inflected. Because the Classical grammar is a snapshot of a language in rapid and profound change, there are duplications and irregularities everywhere. The future tense, in particular, is broken, and has been reconstructed in every language I know that descends from Latin. Add to this an elaborate syntax, an indifference to what we regard as a normal order of words, and a vocabulary that is naturally poor, but expanded by allowing most common words to bear different meanings that must usually be inferred from their context.

This being said, anyone who denies the language is worth learning is a barbarian who deserves to live in the illiterate swamp that we nowadays call civilisation. Without denying the importance of the Greeks, Rome stands at the origin of our literature and law and religion. Latin was, until the late seventeenth century, the normal language of learning and international communication. Directly or indirectly, Latin has given English around sixty per cent of its words. I am not sure if anyone can write English well who is ignorant of Latin. I do not believe anyone can appreciate or notice the full register of our own classical literature without some knowledge of Latin. A further point is that, even today, a qualification in Latin is taken as proof of general intelligence. In short, Latin is a struggle, but a struggle worth undertaking.

Sean Gabb, “A Review of Latin Stories (2018)”, Sean Gabb, 2018-12-23.

October 10, 2021

First the Bloc Québécois, then “Wexit”, now Bloc Montréal?

Barbara Kay makes the case for Montreal to re-evaluate its position within Quebec as the Quebec government pushes toward even more legal efforts to reduce the English-speaking community to a second- or even third-class citizenship:

Oct. 7 brought an end to consultations on Quebec’s Bill 96, which amends the 1977 Charter of the French Language (Bill 101) and — unilaterally, never before attempted by a province — the Constitution Act of 1867. A few anglophone institutions were invited to the hearings, but their inclusion was pro forma. Bill 96 will pass through use of the notwithstanding clause.

The bill affirms Quebec is a nation, with French as its “common” as well as its only official language, adding several new “fundamental language rights” for French. It effectively creates both a Canadian and Quebec Charter-free zone in a wide range of interactions between individuals and the state. Even before passage, use of the P-word (“province”) has become politically charged, and quietly redacted from public usage by Bill 96 dissidents.

The impact of Bill 96 on anglophones could be momentous. One amendment, which restricts access to English health and social services to those with education-eligibility certificates, could negatively affect upwards of 500,000 anglophone Quebecers. It speaks volumes that the Minister of the French Language will take responsibility for outcomes delivery in that sector away from the Minister of Health and Social Services. Bill 96 will also negatively affect young francophones by capping their numbers at English cegeps [Collège d’enseignement général et professionnel or “General and Vocational College”].

The previous expansions of French language rights in Quebec — and corresponding contractions of English language rights in the province — drove waves of emigration to other provinces, helping Toronto surpass Montreal as Canada’s largest city and economic powerhouse. In the middle of a pandemic, it’s much harder for those who are feeling oppressed to leave Quebec, but there may be another possibility:

Montreal as a city-state, or at least a special autonomous region — a status the Cree nation of northern Quebec has enjoyed for decades — was first raised as a serious idea eight years ago. In 2013 the Parti Québécois proposed language Bill 14, as draconian as Bill 96, which died when premier Pauline Marois’s minority government couldn’t enlist enough collegial support for its passage. Nevertheless, the attempt galvanized alarm sufficient to inspire a transiently influential city-state movement.

A 2014 Ipsos poll on the subject commissioned by that group elicited these key takeaways from Montrealers: Montreal is a distinct society within Quebec (90 per cent); to stop its decline, Montreal needs to take drastic steps to improve its performance (91 per cent); and Montreal deserves special status within Quebec because it is a world-class, cosmopolitan city (74 per cent). Those numbers would likely be as high or higher today.

[…]

We need a Bloc Montréal to represent Montreal/Greater Montreal’s “distinct society” at the Quebec National Assembly in Quebec City. The pivotal moment of the 1995 referendum campaign was the revelation — one that had never before occurred to the separatists — that “if Canada is divisible, then Quebec is divisible”. That was a sobering and clarifying moment. And Montreal has a greater need for augmented representation in Quebec City than Quebec has in Ottawa. After all, Quebec profits handsomely from its affiliation with Canada, while the opposite is true of Montreal and Quebec City.

September 26, 2021

QotD: Euphemism

Throughout the Globe piece, neither Robinson nor his interviewer is able to say the words “mentally ill,” let alone crazy. Rather, it is said that he “suffers from a mental illness,” or in Svendspeak, that he is “living with mental illness,” rather like a room-mate. This is a euphemism, a kind of linguistic prophylactic intended to shield the speaker, no less than the listener, from the harsh reality to which it refers. Like all euphemisms and some prophylactics, it will eventually wear out, requiring the substitution of some new euphemism in its place. In time, “living with mental illness” will be seen as a grievous insult, much as “coloured people” is to people of colour. (Except, of course, for those working at the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.)

Andrew Coyne, “False Sensitivity”, andrewcoyne.com, 2005-05-07.

September 6, 2021

QotD: Torturing the English language for “antiracist” ends

I caught a glimpse of Ibram X. Kendi’s recent appearance at the Aspen Ideas Festival, the annual woke, oxygen-deprived hajj for the left-media elites. He was asked to define racism — something you’d think he’d have thought a bit about. This was his response: “Racism is a collection of racist policies that lead to racial inequity that are substantiated by racist ideas.” He does this a lot. He repeats Yoda-stye formulae: “There is no such thing as a nonracist or race-neutral policy … If discrimination is creating equity, then it is antiracist. If discrimination is creating inequity, then it is racist.” These maxims pepper his tomes like deep thoughts in a self-help book. When he proposes specific action to counter racism, for example, he suggests: “Deploy antiracist power to compel or drive from power the unsympathetic racist policymakers in order to institute the antiracist policy.” “Always vote for the leftist” is a bit blunter.

Orwell had Kendi’s number: “The appropriate noises are coming out of his larynx, but his brain is not involved as it would be if he were choosing his words for himself. If the speech he is making is one that he is accustomed to make over and over again, he may be almost unconscious of what he is saying, as one is when one utters the responses in church. And this reduced state of consciousness, if not indispensable, is at any rate favourable to political conformity.” And that conformity is proven by the gawking, moneyed, largely white, Atlantic subscribers hanging on every one of this lightweight’s meaningless words — as if they really were in church.

The most dedicated abusers of the English language, of course, are the alphabet people. They have long since abandoned any pretense at speaking English and instead bombard us with new words: “cisheteropatriarchy”, “homonormativity”, “fraysexuality”, “neutrois”, “transmasculine”, “transmisogynoir”, and on and on. To give you a sense of the completely abstract bullshit involved here, take a style guide given out to journalists by trans activists, instructing them on how to cover transgender questions. (I’m wondering how Orwell would respond if given such a sheet of words he can and cannot use. Let’s just say: not like reporters for the Washington Post.) Here’s the guide’s definition of “gender nonconforming”: “[it] refers to gender presentations outside typical gendered expectations. Note that gender nonconforming is not a synonym for non-binary. While many non-binary people are gender nonconforming, many gender nonconforming people are also cisgender.”

This is a kind of bewildering, private language. But the whole point of the guide is to make it our public language, to force other people to use these invented words, to make the entire society learn and repeat the equivalent of their own post-modern sanskrit. This is our contemporary version of what Orwell went on to describe as “newspeak” in Nineteen Eighty-Four: a vocabulary designed to make certain ideas literally unthinkable because woke language has banished them from use. Repeat the words “structural racism” and “white supremacy” and “cisheteropatriarchy” often enough, and people come to believe these things exist unquestioningly. Talk about the LGBTQIA2S+ community and eventually, people will believe it exists (spoiler alert: it doesn’t).

Andrew Sullivan, “Our Politics and the English Language”, The Weekly Dish, 2021-06-04.

July 24, 2021

A new history of Anglo-Saxon England

At First Things, Francis Young reviews The Anglo-Saxons: A History of the Beginnings of England by Marc Morris:

The art of telling stories will always be closely associated with the Anglo-Saxons. Beowulf, the era’s best-known epic poem, begins with a word that is difficult to translate, summoning an audience to attention: “Hwæt!” The same word opens another great poem of early medieval England, The Dream of the Rood, in which the wood of the Cross speaks and narrates a uniquely Anglo-Saxon Passion — a reminder that it was the Anglo-Saxons who built Christian England.

These people, as Marc Morris observes, were tellers of tales; and yet, until now, there has been no modern narrative history that weaves together the insights of archaeologists, historians, and literary scholars. Morris has risen to the task, tracing the journey of the English-speaking inhabitants of the island of Britain from tribal warbands to a highly sophisticated medieval kingdom on the eve of the Norman Conquest.

This is a triumph of historical storytelling, woven together from the scattered evidence of archaeology, numismatics, chronicles, charters, and many other sources. The narrative that emerges from these difficult sources is, of course, contentious; after all, even the use of the term “Anglo-Saxon” is now debated by scholars. But the narrative is also compelling, rooted in the primary sources, iconoclastic of received interpretations, and — most importantly — the product of a commanding historical imagination. This is an account of the Anglo-Saxons that will inform our perception of them for years to come.

It would be perfectly possible to challenge virtually every one of the author’s interpretations: As Morris notes, “The less evidence, the more contention,” especially when it comes to the chaotic documentary void of the fifth and sixth centuries. (By comparison, by the mid-eleventh century there is a comparative richness of documentary sources.) The first question is about the nature of Germanic immigration after the departure of the Roman legions at the beginning of the fifth century. Morris leans toward a more traditional “replacement” model in which Germanic settlers took the place of the Britons in the landscape. Morris places a great deal of weight on the linguistic evidence, which shows that Brittonic (the language of the Britons) had little influence on Old English. If the Anglo-Saxons had largely assimilated the Britons, rather than replacing them, we might expect many more Brittonic loanwords.

According to Morris, “The broken Britain that the Saxons found … had no allure.” Post-Roman Britain was “in every sense a degraded society, sifting through the detritus of an earlier civilisation.” Morris follows in the tradition of Bede by viewing the Britons as decadent, but this is by no means the only possible view of post-Roman society. Recent scholarship by Miles Russell and Stuart Laycock has drawn attention to Britain’s failure to become Romanized in the first place, raising the question of whether the abandonment of urban life in the early fifth century should be seen as a sign of decline, and Susan Oosthuizen has argued that rural Britain continued to prosper in the absence of urban settlement; it simply thrived on its own terms as a non-urban society.

July 21, 2021

QotD: The expansion of the English vocabulary (through plundering French)

Because French was at that time the international language of trade, it acted as a conduit, sometimes via Latin, for words from the markets of the East. Arabic words that it then gave to English include: “saffron” (safran), “mattress” (materas), “hazard” (hasard), “camphor” (camphre), “alchemy” (alquimie), “lute” (lut), “amber” (ambre), “syrup” (sirop). The word “checkmate” comes through the French “eschec mat” from the Arabic “Sh h m t“, meaning the king is dead. Again, as with virtue and as with hundreds of the words already mentioned, a word, at its simplest, is a window. In that case, English was perhaps as much threatened by light as by darkness, as much in danger of being blinded by these new revelations as buried under their weight.

Yet the best of English somehow managed to avoid both these fates. It retained its grammar, it held on to its basic words, it kept its nerve, but what it did most remarkably was to accept and absorb French as a layering, not as a replacement but as an enricher. It had begun to do that when Old English met Old Norse: hide/skin; craft/skill. Now it exercised all its powers before a far mightier opponent. The acceptance of the Norse had been limited in terms of vocabulary. Here English was Tom Thumb. But it worked in the same way.

So, a young English hare came to be named by the French word “leveret“, but “hare” was not displaced. Similarly with English “swan”, French “cygnet“. A small English “axe” is a French “hatchet“. “Axe” remained. There are hundreds of examples of this, of English as it were taking a punch but not giving ground.

More subtle distinctions were set in train. “Ask” – English – and “demand” – from French – were initially used for the same purpose but even in the Middle Ages their finer meanings might have differed and now, though close, we use them for markedly different purposes. “I ask you for ten pounds”; “I demand ten pounds”: two wholly different stories. But both words remained. So do “bit” and “morsel”, “wish” and “desire”, “room” and “chamber”. At the time the French might have expected to displace the English. It did not and perhaps the chief reason for that is that people saw the possibilities of increasing clarity of thought, accuracy of expression by refining meaning between two words supposed to be the same. On the surface some of these appear to be interchangeable and sometimes they are. But much more interesting are these fine differences, whose subtleties increase as time carries them first a hair’s breadth apart and then widens the gap, multiplies the distinctions: just as “ask” has evolved far away from “demand”.

Not only did they drift apart but something else happened which demonstrates how deeply not only history but class is buried in language. You can take an (English) “bit” of cheese and most people do. If you want to use a more elegant word you take a (French) “morsel” of cheese. It is undoubtedly thought to be a better class of word and yet “bit”, I think, might prove to have more stamina. You can “start” a meeting or you can “commence” a meeting. Again, “commence” carries a touch more cultural clout though “start” has the better sound and meaning to it for my ear. But it was the embrace which was the triumph, the coupling which was never quite one.

That’s the beauty of it. That was the sweet revenge which English took on French: it not only anglicised it, it used the invasion to increase its own strength; it looted the looters, plundered those who had plundered, out of weakness brought forth strength. For “answer” is not quite “respond”; now they have almost independent lives. “Liberty” isn’t always “freedom”. Shades of meaning, representing shades of thought, were massively absorbed into our language and our imagination at that time. It was new lamps and old; both. The extensive range of what I would call “almost synonyms” became one of the glories of the English language, giving it astonishing precision and flexibility, allowing its speakers and writers over the centuries to discover what seemed to be exactly the right word.

Rather than replace English, French was being brought into service to help enrich and equip it for the role it was on its way to reassuming.

Melvyn Bragg, The Adventure of English, as quoted by Brian Micklethwait, “Melvyn Bragg on England’s verbal twins”, Samizdata, 2018-12-23.

July 18, 2021

A different kind of “tone policing”

John McWhorter on a recent study on interactions between the police and the general population:

“Police stop” by San Diego Shooter is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

A fascinating, and depressing, new study will be celebrated as revealing the subtle but powerful operations of racism. It also reveals, however, the pitfalls in the way we are taught to address that racism these days.

The study shows that police officers tend to talk in a less friendly way to black people they stop than white ones. People were played slivers of body-cam audio of the officers talking to citizens, with the content of the exchange disguised. People could tell with dismaying regularity what color person the officer was speaking to simply by the tone of voice. It wasn’t that officers outright sneer at black people. Rather, their tone with whites tends to be more pleasant, to have a hint of cheer, whereas with black people it is more impersonal, flat, unwarm.

The study also shows how these things fashion a vicious cycle. People tested who had negative experiences with cops and/or less trust in them processed even the exchanges the cops had with white citizens as less positive than other people tested did. That is, their life experience has implanted in them a distrust of the cops, that can anticipate actual interactions with them – and certainly, of course, unintentionally pollute them.

* * *

This study reminds me of something else that goes in the other direction. To whites, subtle things about black communication, including vocal tone, can come off as threatening when no threat is intended.

I once happened to hear two 30-something black men talking about a misunderstanding one of them had had at work. They were just unwinding, but there was what many might process as a tinge of impending battle in their voices, inflections and gestures. “Man, I wanted to ‘Mmmph!’ [jab of the arm, click of the tongue] Gimme a break! An’ I was like … [putting on a challenging glare] don’t even start.”

No black listener would assume these guys actually meant the hints at violence literally. However, outside listeners can hear this way of talking as edgy. Kelefa Sanneh’s term for this twenty years ago, writing about rap and its lyrics, was perfect: a certain “confrontational cadence”.

Yes, all people trash-talk. But this particular way of talking has a special place in black American culture. No, that’s not stereotyping: sympathetic black academics have documented it. CUNY’s Arthur Spears, today one of the deans of the academic study of black American speech, has written about what he calls “directness”. Speech “that may appear to outsiders to be abusive or insulting is not necessarily intended to be nor is it taken that way by audiences and addressees,” Spears noted. He then quoted a father-child exchange: Father: “Go to bed!” Little boy: “Aw, Daddy, we’re playing dominoes.” Father: “I’m gonna domino your ass if you don’t go to bed now.” Notice how awkwardly this, or Eddie Murphy’s routine about the mother throwing the shoe in Delirious, would translate into the world of Modern Family.

This “confrontational cadence” can inflect even casual exchanges between black and white people. Aspects of black intonation, steeped in a lifetime’s experience in a language culture that values performative aggression as a kind of communal élan, can sound cranky, disrepectful, and even aggressive to a white person. It is all but impossible that this does not color encounters between black people and white cops; I highly suspect a study like the first one I mentioned would reveal it.

July 7, 2021

QotD: Bad language from Down Under

Barry McKenzie, Australian at Large, made his debut in the 10 July 1964 issue of Private Eye. He was the creation of the comedian Barry Humphries, then, like a number of other creative Aussie expats, resident in London. Hero of a new strip cartoon, illustrations by Nicholas Garland, Bazza, as he would become known, was identified in this first outing as “a strapping young specimen of Australian manhood” and self-described as “an ordinary honest working-class bloke”. His first words “Excuse I, what’s gone flaming wrong?” informed readers that they were in the presence of an antipodean Candide, the classic hick, come to the big city and ready to surf on a tide of Foster’s lager into what within a year would be apostrophised as “Swinging London”.

Naive he surely was — and while over his nine-year career at the Eye he might increasingly turn the tables on the Brits, that innocence never wholly disappeared — in one respect he was omnipotent. His slang-laden, all-Australian language burst into the Eye reader’s consciousness fully-formed and quite astounding. By 1968 Bazza was offering freckle puncher, smell like an Abo’s armpit, bang like a shithouse door, dry as a nun’s nasty, point Percy at the porcelain, siphon the python and perhaps the most celebrated, the Technicolour yawn (aka the liquid laugh or the big spit).

[…]

It was also resolutely carnal: in its concentration on defecation and urination, drinking (and the seemingly inevitable vomiting it induced) and copulation (even if Bazza remains the eternal virgin), Humphries either created or collated a vocabulary that would not be rivalled until Viz magazine’s “swearing dictionary” Roger’s Profanisaurus began appearing in 1997.

Rooted, from Amanda Laugesen, director of the Australian National Dictionary Centre at the Australian National University and chief editor of the Australian National Dictionary, focuses on this side of the Australian vocabulary. Rooted comes from root, a euphemism for fuck, both literally, in the context of sex, and figuratively, as in harm, destroy, and so on. It falls into what Laugesen is happy to term “bad language”, even if one might suspect that with her formidable knowledge it is a term she knows perfectly well is a construct of tabloid moralising and empty religiosity. (Perhaps I am hardened by proximity, but I find it sad she feels the need to warn readers they will encounter the language that is the subject of her work.)

Jonathon Green, “Fair dinkum dictionary”, The Critic, 2021-04-08.