The thing is, you don’t have to be an expert on everything. Simply knowing the basics and the relevance is enough in many cases. You have the entirety of human knowledge at your fingertips so knowing how to look things up is more important than memorization. Einstein allegedly said he had no reason to memorize how many feet were in a mile because he could find in any book. Today, you can find the details off your phone or laptop in seconds. What you need is an understanding of how to find it.

That’s the first thing a modern person needs to know. How to look things up on-line is an essential skill in the modern age. Working with young interns years ago, I was surprised to discover that none of them knew how to be curious. I had to teach them how to find things on-line. They had no idea how to discover the world by inference. What I ended up telling them is always ask what a thing is, not where a thing is. What is its nature, what does it do. Who thinks it is important. Enter those things in a search engine and you will get close to what you seek.

This is probably obvious to most reading this, but there is a reason browsers have bookmarks and there are services that let you synchronize your bookmarks on all of your devices. Most people store knowledge and then remember where they left it. That has its place, but when searching for things on-line, you may, whether you realize it or not, be looking for unknown unknowns. By thinking about what a thing or event is, you will find things like it or related to it that you never considered or simply did not know existed.

This will no doubt strike some as pedantic, but in the modern age, the ability to quickly acquire necessary information is probably the most valuable skill and therefore, the most essential of knowledge. All of us have at our fingertips the totality of human understanding. Knowing how to quickly dig through it to find what it is you need is vastly more useful and important than the ability to remember how many feet are in a mile or where the book you learned it is on your book shelf.

The Z Man, “Essential Knowledge Part I”, The Z Blog, 2017-01-13.

February 14, 2019

QotD: Knowing how to find out is an essential skill

January 31, 2019

Coming soon for Canadians – mandatory maple-flavoured search results

Michael Geist relates the ongoing efforts of ACTRA to get the federal government to mandate high visibility for Canadian content in search engines:

The escalating battle being waged for new Internet taxes to fund Canadian content does not stop with proposals for new fees on Internet access and online video services. Cultural groups also want to increase the “discoverability” of Canadian content by mandating its inclusion in search results. According to the ACTRA submission to the broadcast and telecom legislative review panel, it has been calling for search engine regulation for the past 20 years:

ACTRA stated during the 1999 CRTC process that Internet search engines would become the gateway for consumers to access the vast array of entertainment and information now available from around the world. We argued then the CRTC should regulate them.

It now argues for mandated inclusion of Canadian content in search results for cultural content under threat of economic sanction:

Regulating search engines would be difficult, but ACTRA recommends the government approach search engines like Google, Bing and others, and request they ensure Canadians are offered some Canadian choices in their search results. While it is neither possible nor appropriate to interfere in the final selection made by individuals, Canadian consumers should have a real choice, including Canadian films, television programs and music. We expect companies would concur with the government’s reasonable request to be seen as good corporate citizens. If a particular search engine does not agree to this request, the government should impose an appropriate regulatory constraint or burden, such as amending the Income Tax Act to discourage Canadians from advertising on search engines that fail to comply.

June 30, 2018

Adventures in Sicilian non-verbal communication

At El Reg, Alistair Dabbs recounts some tales from a recent trip to Italy:

This isn’t the first time I have strayed into a Twilight Zone of cross-lingual and intercultural bafflement during this vacation. Throwing caution to the wind a few days earlier, I’d rashly allowed Google Maps to plot a walking route from the centre of Palermo to La Zisa. Why I did this, I cannot say, especially given my poor experience of Google Maps’ walking routes in the past. This is, after all, the app that once directed me to walk through the centre of an unlit Hyde Park at 2am and whose audio inexplicably but routinely barks “Turn left!” when you’re supposed to turn right.

On this occasion, Google Maps decided to take me on a scenic tour of the city’s most impoverished slums. Given that what few pavements existed along the way were knee high in refuse and canine excretia, it was less of a walking route than a wading route. The final 100 metres appeared to be some kind of theme park attraction along the lines of Disney World’s “Pirates of the Caribbean”, except this was “Dope-addled Inbreds of the Mediterranean”.

To access this den of iniquità, I had to pass through one of those pedestrian gates design to stop cyclists from riding through it. It was blocked by a tweenager who’d been trying to ride his bicycle through it and got stuck. The unlikely resolution of such an attempt was emphasised by two obvious challenges: it was an adult bike and the boy was so fat that he looked like an inflatable sofa. Both the bicycle and his body were at least two sizes too big for him.

By waving his arms around, he indicated that I was welcome to pass through the gate. By waving my arms back at him, I indicated that I would certainly do so after he had extricated himself. This attracted some shifty onlookers who helpfully grunted and waved their arms around at both of us until eventually we were all gesticulating like delegates at a semaphore convention.

Fearing an unfortunate outcome from this clash of cultures in unfamiliar territory, I coaxed the fat kid and his bike out of the gate and taught him to play the banjo he was carrying, ending with a spontaneous duet between the two of us. It was only by sheer luck that I’d remembered to pack my bagpipes.

Enriching the public in ways that do not show up in the GDP calculations

Tim Worstall looks at the calls to regulate the big tech firms and points out that we already get a very good deal on “free stuff” that isn’t reflected in standard economic statistics:

It won’t have escaped your attention that rather large numbers of people are calling for the regulation of the tech companies. The Amazon, Google, Facebook (Apple and Microsoft often added, just because they’re large) nexus have lots of power over markets and thus therefore – well, therefore something. My own prejudice here is that certain people just cannot look at centres of power and or money without insisting that they, the complainers, should be the ones exercising that power and determining the disposition of that money. Thus much of the drive for “democratic” regulation of the economy more generally, the self proclaimed democrats being the ones who would end up with the power. The advantage of this analysis being that it does describe reality, the same people do end up making the same arguments about different companies over time. Mere prominence brings the demand for control.

The economist on this subject is Jean Tirole. His Nobel was for exploring this very subject, tech companies and the two sided market. Google, for example, sells the search engine to us and us to the advertisers. The tech here is different, obviously, but the underlying economics is the same as that of the free newspaper.

Tirole’s a new book out and there are a number of interesting points to be had from it:

Yes, on the whole consumers tend to get a good deal, because we use wonderful services — like Google’s search engine, Gmail, YouTube, and Waze — for free. To be certain, we are not paid for the valuable data we provide to the platforms, as for example Eric Posner and Glen Weyl remind us in their recent book Radical Markets. But on the whole, our living standards have substantially improved thanks to the digital revolution.

From which we can extract a few points. We’re richer, we really are. Substantially richer and yet in a manner that normal economic statistics entirely fail to capture. As Hal Varian has pointed out, GDP doesn’t deal well with free. Near all of those benefits of the digital revolution are coming to us for free and so aren’t recorded in that GDP. So, we’re richer yet the numbers say we’re not. In that is much of the explanation of slow economic growth these days, even of slow real wage growth. We’re just not counting what is happening to our living standards.

But we can and should go further than that. If the above is true then we’re very much less unequal than we’re recording. Stuff that’s free is, obviously enough, distributed rather more evenly among the population than extant monetary incomes. You, me and Bill Gates all have access to exactly the same amount of Facebook at the same price. We’re entirely equal in that sense. Bill’s actually poorer concerning search engines, stuck for emotional reasons with Bing as he is while we get to use Google or DuckDuckGo. Our standard measures of inequality are wrong both because of the undermeasurement of new wealth and also the extremely equitable pattern of the distribution of that new wealth.

May 6, 2018

March 29, 2018

February 19, 2018

Google disappears the “View Image” button from their image search page

At Ars Technica, Ron Amadeo explains what happened:

This week, Google Image Search is getting a lot less useful, with the removal of the “View Image” button. Before, users could search for an image and click the “View Image” button to download it directly without leaving Google or visiting the website. Now, Google Images is removing that button, hoping to encourage users to click through to the hosting website if they want to download an image.

Google’s Search Liaison, Danny Sullivan, announced the change on Twitter yesterday, saying it would “help connect users and useful websites.” Later Sullivan admitted that “these changes came about in part due to our settlement with Getty Images this week” and that “they are designed to strike a balance between serving user needs and publisher concerns, both stakeholders we value.”

[…] Adhering to copyright law is still the user’s responsibility, and a whole lot of images on the Web aren’t locked down under copyright law. There are tons of public domain and creative commons images out there (like everything on Wikipedia, for instance), and lots of organizations are free to use many copyrighted images under fair use. There are also many times when content on a page will change, and the “visit site” button will go to a webpage that doesn’t have the image Google told you it had.

For users who want to stick with Google, the image previews you see are actually hot-linked images, so right clicking and choosing “open image in new tab” (or whatever your equivalent browser option is) will still get you a direct image link. There is also already an open source browser extension called “Make Google Image Search Great Again” that will restore the “View Image” button. But if you’re looking to dump Google over this change, Bing and DuckDuckGo continue to offer “View Image” buttons.

Concerns about copyright are a big reason I tend to use Wikimedia or other clearly public domain images when I want to add one to a blog post.

January 31, 2018

QotD: “Enhancing the user experience”

Once upon a time, computers weren’t all constantly connected to the intertubes. What we call “air-gapped” these days was the normal state of machines back in the desktop beige box days.

Back then, when you bought a program it came in a cardboard box on physical media. You would install it on your computer and it would work the same way from the day you installed it to the day you stopped using it. Nobody could rearrange the menus on WordPerfect or change the buttons in Secret Weapons of the Lufwaffe … Good times.

Nowadays, half the software you interact with doesn’t even reside on your PC. Further, there are whole departments at, say, Facebook or Blizzard or Google whose entire job is to “enhance the user experience”. If they’re not constantly dicking around, adding and removing features, changing what buttons do, moving things around … then they’re not doing their jobs.

We have incentivized instability.

Tamara Keel, “Tinkering for tinkering’s sake…”, View From The Porch, 2018-01-10.

January 18, 2018

Weird lawsuit filed against Waymo engineer

In The Register, Kieren McCarthy reports on the case:

The engineer at the center of a massive self-driving car lawsuit – brought by Google-stablemate Waymo against Uber – neglects his kids, is wildly disorganized, and has a large selection of bondage gear, his former nanny has sensationally alleged.

Anthony Levandowski may also be paying a Tesla techie for trade secrets, may have secretly helped set up several self-driving car startups, and at one point planned to flee across the border to Canada in an effort to avoid the legal repercussions of his actions at both Waymo and Uber, it is further claimed.

Those extraordinary allegations come in a highly unusual lawsuit [PDF] filed earlier this month by his ex-nanny Erika Wong, who worked for Waymo’s former star engineer for six months, from December 2016 to June 2017.

Wong’s lawsuit identifies no less than 41 causes of action – ranging from alleged health and safety code violations to emotional distress – and asks for a mind-bogglingly $6m in recompense. Levandowski’s lawyer said the lawsuit is a “work of fiction.”

Not safe for work bits below the fold:

January 14, 2018

Google’s unhealthy political monoculture

Megan McArdle doesn’t think that the lawsuit that James Damore is pursuing against Google has a lot of legal merit, but despite that she’s confident that the outcome won’t be happy for the corporation:

The lawsuit, just filed in a California court, certainly offers evidence that things were uncomfortable for conservatives at Google. And especially, that they were uncomfortable for James Damore after he wrote a memo suggesting that before Google went all-out trying to achieve gender parity in its teams, it needed to be open to the possibility that the reason there were fewer women at the firm is that fewer women were interested in coding. (Or at least, in coding with the single-minded, nay, obsessive, fervor necessary to become an engineer at one of the top tech companies in the world.)

That much seems quite clear. But it’s less clear that Damore has a strong legal claim.

I understand why conservative employees were aggrieved. Internal communications cited in the lawsuit paint a picture of an unhealthy political monoculture in which many employees seem unable to handle any challenge to their political views. I personally would find it extremely unsettling to work in such a place, and I am a right-leaning libertarian who has spent most of my working life in an industry that skews left by about 90 percent.

But these internal communications have been stripped of context. Were they part of a larger conversation in which these comments seem more reasonable? What percentage did these constitute of internal communications about politics? At a huge company, there will be, at any given moment, some number of idiots suggesting things that are illegal, immoral or merely egregiously dumb. That doesn’t mean that those things were corporate policy, or even that they were particularly problematic for conservatives. When Google presents its side of the case, the abuses suggested by the lawsuit may turn out to be considerably less exciting — or a court may find that however unhappy conservatives were made by them, they do not rise to a legally actionable level.

Google, for its part, says that it is eager to defend the lawsuit. But lawyers always announce that they have a sterling case that is certain to prevail, even if they know they are doomed. And unless they can present strong evidence that there were legions of conservatives happily frolicking away on their internal message boards while enjoying the esteem of their colleagues and the adulation of their managers, there is no way that this suit ends well for Google. If the company and its lawyers think otherwise, they are guilty of a sin known to the media as “reading your own press releases,” and to drug policy experts as being “high on your own supply.”

There are expensive, time-consuming, exasperating lawsuits, and then there are radioactive lawsuits that poison everyone who comes within a mile of them. And this lawsuit almost certainly falls into the latter category.

December 1, 2017

Censorship on the web

At City Journal, Aaron Renn explains why some of the concerns about censorship on the Internet are not so much wrong as misdirected:

The basic idea of net neutrality makes sense. When I get a phone, the phone company can’t decide whom I can call, or how good the call quality should be depending on who is on the other end of the line. Similarly, when I pay for my cable modem, I should be able to use the bandwidth I paid for to surf any website, not get a better or worse connection depending on whether my cable company cut some side deal to make Netflix perform better than Hulu.

The problem for net neutrality advocates is that the ISPs aren’t actually doing any of this; they really are providing an open Internet, as promised. The same is not true of the companies pushing net neutrality, however. As Pai suggests, the real threat to an open Internet doesn’t come from your cable company but from Google/YouTube, Twitter, Facebook, and others. All these firms have aggressively censored.

For example, Google recently kicked would-be Twitter competitor Gab out of its app store, not for anything Gab did but for what it refused to do — censor content. Twitter is famous for censoring, as Pai observes. “I love Twitter, and I use it all the time,” he said. “But let’s not kid ourselves; when it comes to an open Internet, Twitter is part of the problem. The company has a viewpoint and uses that viewpoint to discriminate.” (Twitter’s censors have not gotten around to removing the abuse, some of it racist, being hurled at Pai, including messages like “Die faggot die” and “Hey go fuck yourself you Taliban-looking fuck.”)

Google’s YouTube unit also censors, setting the channel for Prager University to restricted mode, which limits access; Prager U. is suing Google and YouTube. YouTube has also “demonetized” videos from independent content creators, making these videos ineligible for advertising, their main source of revenue. Much of the complaining about censorship has come from political conservatives, but they’re not the only victims. The problem is broad-based.

Yet sometimes Silicon Valley giants have adopted a see-no-evil approach to certain kinds of content. Facebook, for instance, has banned legitimate content but failed to stop Russian bots from going wild during last year’s presidential election, planting voluminous fake news stories. Advertisers recently started fleeing YouTube when reports surfaced that large numbers of child-exploitation videos were showing up on supposedly kid-friendly channels. One account, ToyFreaks, had 8 million subscribers — making it the 68th most-viewed YouTube channel — before the company shut it down. It’s not credible that YouTube didn’t know what was happening on a channel with millions of viewers. Other channels and videos featured content from pedophiles. More problems turned up within the last week. A search for “How do I …” on YouTube returned numerous auto-complete suggestions involving sex with children. Others have found a whole genre of “guess her age” videos, with preview images, printed in giant fonts, saying things like, “She’s only 9!” The videos may or may not have involved minors — I didn’t watch them—but at minimum, they trade on pedophilic language to generate views.

September 15, 2017

Will Google’s quasi-monopoly last as long as AOL’s did?

In the big picture, I’m concerned with Google’s current market power and their ability to quash online freedom of speech almost at will (if not directly, through pressure on other companies to co-operate, or else: “Nice little business you’ve got here, Mr. Forbes. It’d be a shame if something happened to its Google search results…”). Google is huge and has fingers in an unimaginable number of pies, but it is still subject to market forces, as was an earlier behemoth of the online world:

The film [You’ve Got Mail] was released in 1998. Amazon was founded in 1994 and had its IPO in 1997. It was about to crush big discount bookstores — does anyone still remember the other big chain, Borders? — and nobody had a clue. There isn’t a single mention in the film of Amazon or online sales.

But the Internet is mentioned. It’s right there in the title of the movie. You’ve Got Mail, for those who are old enough to remember, was a tagline for America Online, the largest Internet service provider in the dial-up era of the 1990s. For millennials, let me explain: we had to connect our computers to a phone line, and an internal modem would place a phone call to a local data center from which it could download information at impossibly slow speeds. […]

AOL is there in the film’s title, because that’s how our protagonists are communicating: by trading e-mails on their dial-up AOL connections.

AOL’s high point was its merger with Time Warner in 2000. It was all downhill, rapidly, from there. Dial-up was quickly surpassed by broadband, and as the Web developed, nobody needed a “Web portal” any more. Again, for younger readers, let me explain. When you managed to get to this exciting new thing called the World Wide Web, how did you know what sites to go to or how to access information? Before the Google search, before Facebook, before Twitter, you went to a Web portal, a launching off point that gathered links and directed you to various sources for news, entertainment, shopping, etc. These Web portals had a huge amount of influence — until they didn’t.

Now here’s the fun part. At the same time nobody was paying much attention to Amazon because Barnes and Noble was going to crush all competitors and control the book business, there was widespread panic about the unstoppable monopoly power of AOL.

AOL was going to gain a monopoly because of its death grip on instant messaging. The “computer editor” for The Guardian worried that this was putting AOL “on its way to world domination.” The AOL-Time Warner deal raised “concerns that its merger would create a media powerhouse that would level competitors, dominate the Internet, and control consumer choice.”

A Wired podcast talked about fears of a Sun-AOL monopoly, but they didn’t call that sort of thing a “podcast” yet because the iPod hadn’t been invented. The audio clip was an MP3 file, and they suggested you listen to it on a Sonique MP3 player from Lycos. The Sonique stopped being produced about a year later. Lycos was a major Web portal, and according to Wikipedia, it was “the most visited online destination in the world in 1999.” It was bought by a multinational conglomerate for $12.5 billion at the peak of the dot-com bubble.

Whatever is left of Lycos was last sold for $36 million in 2010, though that deal seems to have collapsed in acrimony later on. Sic transit gloria mundi.

September 12, 2017

Google doesn’t mind flexing its muscles now and again

Yet another instance of Google proving that someone erased the word “Don’t” from their company motto*:

Dear Editors,

You might be interested to learn, that your websites have been almost blacklisted by Google. “Almost blacklisted” means that Google search artificially downranks results from your websites to such extent that you lose 55% – 75% of possible visitors traffic from Google. This sitution [sic] is probably aggravated by secondary effects, because many users and webmasters see Google ranking as a signal of trust.

This result is reported in my paper published in WUWT. The findings are consistent with multiple prior results, showing Google left/liberal bias, and pro-Hillary skew of Google search in the elections.

I write to all of them to give you opportunity to discuss this matter among yourselves. Even if Google owes nothing to your publications, it certainly owes good faith to the users of its search.

* For all I know, Google’s original motto may already have gone down the memory hole: “Don’t be evil“.

September 8, 2017

Google’s unbridled market power and ability to quash critics and competitors

In Wired, Rowland Manthorpe reports on another case of Google roughing up someone for being critical of their current “be evil” business philosophy:

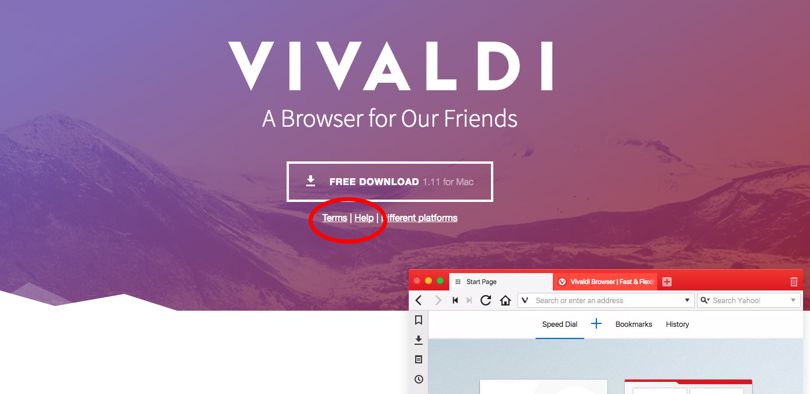

The latest allegation against Google? Jon von Tetzchner, creator of the web browser Opera, says the search giant deliberately undermined his new browser, Vivaldi.

In a blogpost titled, “My friends at Google: it is time to return to not being evil,” von Tetzchner accuses the US firm of blocking Vivaldi’s access to Google AdWords, the advertisements that run alongside search results, without warning or proper explanation.

According to Von Tetzchner, the problem started in late May. Speaking at the Oslo Freedom Forum, the Icelandic programmer criticised big tech companies’ attitude toward personal data, calling for a ban on location tracking on Facebook and Google. Two days later, he suddenly found Vivaldi’s Google AdWords campaigns had been suspended. “Was this just a coincidence?” he writes. “Or was it deliberate, a way of sending us a message?” He concludes: “Timing spoke volumes.”

Von Tetzchner got in touch with Google to try and resolve the issue. The result? What he calls “a clarification masqueraded in the form of vague terms and conditions.” The particular issue was the end-user license agreement (EULA), the legal contract between a software manufacturer and a user. Google wanted Vivaldi to add one to its website. So it did. But Google had further complaints.

According to emails shown to WIRED, Google wanted Vivaldi to add an EULA “within the frame of every download button”. The addition was small – a link below the button directing people to “terms” – but on the web, where every pixel matters, this was a potential competitive disadvantage. Most gallingly, Chrome, Google’s own web browser, didn’t display a EULA on its landing pages. Google also asked Vivaldi to add detailed information to help people uninstall it, with another link, also under the button.