Some critics do not fault [Nineteen Eighty-Four] on artistic grounds, but rather judge its vision of the future as wildly off-base. For them, Orwell is a naïve prophet. Treating Orwell as a failed forecaster of futuristic trends, some professional “futurologists” have catalogued no fewer than 160 “predictions” that they claim are identifiable in Orwell’s allegedly poorly imagined novel, pertaining to the technical gadgetry, the geopolitical alignments, and the historical timetable.

Admittedly, if Orwell was aiming to prophesy, he misfired. Oceania is a world in which the ruling elite espouses no ideology except the brutal insistence that “might makes right”. Tyrannical regimes today still promote ideological orthodoxy — and punish public protest, organized dissidence, and conspicuous deviation. (Just ask broad swaths of the citizenry in places such as North Korea, Venezuela, Cuba, and mainland China.) Moreover, the Party in Oceania mostly ignores “the proles”. Barely able to subsist, they are regarded by the regime as harmless. The Party does not bother to monitor or indoctrinate them, which is not at all the case with the “Little Brothers” that have succeeded Hitler and Stalin on the world stage.

Rather than promulgate ideological doctrines and dogmas, the Party of Oceania exalts power, promotes leader worship, and builds cults of personality. In Room 101, O’Brien douses Winston’s vestigial hope to resist the brainwashing or at least to leave some scrap of a legacy that might give other rebels hope. “Imagine,” declares O’Brien, “a boot stamping on a human face — forever.” That is the future, he says, and nothing else. Hatred in Oceania is fomented by periodic “Hate Week” rallies where the Outer Party members bleat “Two Minutes Hate” chants, threatening death to the ever-changing enemy. (Critics of the Trump rallies during and since the presidential campaign compare the chants of his supporters — such as “Lock Her Up” about “Crooked Hillary” Clinton and her alleged crimes — to the Hate Week rallies in Nineteen Eighty-Four.)

Yet all of these complaints about the purported shortcomings of Nineteen Eighty-Four miss the central point. If Orwell “erred” in his predictions about the future, that was predictable — because he wasn’t aiming to “predict” or “forecast” the future. His book was not a prophecy; it was — and remains — a warning. Furthermore, the warning expressed by Orwell was so potent that this work of fiction helped prevent such a dire future from being realized. So effective were the sirens of the sentinel that the predictions of the “prophet” never were fulfilled.

Nineteen Eighty-Four voices Orwell’s still-relevant warning of what might have happened if certain global trends of the early postwar era had continued. And these trends — privacy invasion, corruption of language, cultural drivel and mental debris (prolefeed), bowdlerization (or “rectification”) of history, vanquishing of objective truth — persist in our own time. Orwell was right to warn his readers in the immediate aftermath of the defeat of Hitler and the still regnant Stalin in 1949. And his alarms still resound in the 21st century. Setting aside arguments about forecasting, it is indisputable that surveillance in certain locales, including in the “free” world of the West, resembles Big Brother’s “telescreens” everywhere in Oceania, which undermine all possibility of personal privacy. For instance, in 2013, it was estimated that England had 5.9 million CCTV cameras in operation. The case is comparable in many European and American places, especially in urban centers. (Ironically, it was revealed not long ago that the George Orwell Square in downtown Barcelona — christened to honor him for his fighting against the fascists in the Spanish Civil War — boasts several hidden security cameras.)

Cameras are just one, almost old-fashioned technology that violates our privacy, and our freedoms of speech and association. The power of Amazon, Google, Facebook, and other web systems to track our everyday activities is far beyond anything that Orwell imagined. What would he think of present-day mobile phones?

John Rodden and John Rossi, “George Orwell Warned Us, But Was Anyone Listening?”, The American Conservative, 2019-10-02.

December 31, 2023

QotD: Orwell as a “failed prophet”

December 16, 2023

QotD: British meals – potatoes

It is necessary here to say something about the specifically British ways of cooking potatoes. Roast meat is always served with potatoes “cooked under the joint”, which is probably the best of all ways of cooking them. The potatoes are peeled and placed in the pan all round the roasting meat, so that they absorb its juices and then become delightfully browned and crisp all over. Another method is to bake them whole in their jackets, after which they are cut open and a dab of butter is placed in the middle. In the North of England delicious potato cakes are made of mashed potatoes and flour: these are rolled out into small round pancakes which are baked on a griddle and then spread with butter. New potatoes are generally boiled in water containing a few leaves of mint and served with melted butter poured over them.

George Orwell, “British Cookery”, 1946. (Originally commissioned by the British Council, but refused by them and later published in abbreviated form.)

December 5, 2023

QotD: British meals – the midday meal

Before one can discuss the midday meal […] it is necessary to explain away the mysteries of “lunch”, “dinner” and “high tea”. The actual diet of the richer and poorer classes in Britain does not vary very greatly, but they use a different nomenclature and time their meals differently, because certain habits adopted from France during the past hundred years have not yet reached the great masses.

The richer classes have their midday meal at one-thirty in the afternoon and call it “luncheon”. At about half-past four in the afternoon they have a cup of tea and perhaps a piece of bread-and-butter or a slice of cake, which they call “afternoon tea” and they have their evening meal at half-past seven or eight, and call it “dinner”. The others, perhaps ninety percent of the population, have their midday meal somewhat earlier – usually about half-past twelve – and call it “dinner”. They have their main evening meal at about half-past six and call it “tea” and before going to bed they have a light snack – for instance cocoa and bread-and-jam – which they call “supper”. The distinction is regional as well as social. In the North of England, Scotland and Ireland many well-to-do people prefer to follow the working-class time scheme, partly because it fits in better with the working day, and partly, perhaps, from motives of conservation: for our ancestors of a century ago also had their meals at approximately these hours.

But though the name and the hour may differ, every British person’s idea of midday meal is approximately the same. We are not here concerned with the quasi-French meals that are served in hotels, but solely with British cookery, and therefore we can leave both soups and hors d’oeuvres out of account. Most British people are inclined to despise both, and do not care for them in the middle of the day. British soups are seldom good, and there is hardly a single one that is peculiar to the British Isles, while even the word “hors d’oeuvre” has no equivalent in the British language. The British midday meal consists essentially of meat, preferably roast meat, a heavy pudding, and cheese. And here one comes upon the central institution of British life, the “joint”: that is, a large piece of meat – round of beef or leg of pork or mutton – roasted whole with its potatoes round it, and preserving a flavour and a juiciness which meat cooked in smaller quantities never seems to attain.

Most characteristic of all is roast beef, and of all the cuts of beef, the sirloin is the best. It is always roasted lightly enough to be red in the middle: pork and mutton are roasted more thoroughly. Beef is carved in wafer-thin slices, mutton in thick slices. With beef there nearly always goes Yorkshire pudding, which is a sort of crisp pancake made of milk, flour and eggs and which is delicious when sodden with gravy. In some parts of the country suet pudding is eaten with roast beef instead of Yorkshire pudding. Sometimes instead of roasted fresh beef there is boiled salt beef, which is always eaten with suet dumplings and carrots or turnips.

[…]

In the second half of the midday meal we come upon one of the greatest glories of British cookery – its puddings. The number of these is so enormous that it would be impossible to give an exhaustive list, but, putting aside stewed fruits, British puddings can be classified under three main heads: suet puddings, pies and tarts, and milk puddings.

[…]

If the midday meal ends with cheese, that cheese will probably be foreign. Some of the cheeses native to Britain are very good, but they are not produced in large quantities and are mostly consumed locally. The best of them is Stilton, a cheese rather the same kind as Roquefort or Gorgonzola, but stronger-tasting and closer in the grain. Wensleydale, a similar but milder cheese, is also very good.

George Orwell, “British Cookery”, 1946. (Originally commissioned by the British Council, but refused by them and later published in abbreviated form.)

October 31, 2023

QotD: Orwell’s “hero” in Nineteen Eighty-Four

Like virtually all utopian or anti-utopian satires, Nineteen Eighty-Four presents drab, flat characters living in a grim world. Their journeys are predictable because their freedoms are narrow, often nonexistent and merely imagined. You cannot judge this book by the conventional criteria signaling a “good” novel. Even the main characters are not three-dimensional figures.

That is how it should be. What would you expect? In a world like this, it would be inconsistent, if not contradictory, to portray human beings who are not stunted and who live exciting lives with unexpected plot twists and turns.

Yet there is a hero in this anti-utopia, and Orwell’s magnificent portrait exemplifies its consummate artistry. The multidimensional, richly drawn “hero” is none other than the setting — that is, the empire of Oceania itself. Its history, its corrupt and tyrannical ruling Party, its oppressive and terrifying technology, its ingenious propagandistic language (“Newspeak”), its hatred of the body and sexuality (Julia belongs to — and pretends to support — the Junior Anti-Sex League): all this makes it a rounded, fascinating, creatively elaborated “character”. And there is no room for any other. Because Oceania is omnipotent and omniscient, it determines that its citizenry — whether prole or Party leader — is a cipher. The setting is, as it were, the (pseudo-Marxist) substructure; the superstructure of character and plot are determined by and beholden to it, utterly secondary and “superfluous” by comparison.

Orwell created an unforgettable, terrifying character — Oceania — and showed its “development” (in the spheres of technology, language, warfare, geopolitics, state torture, social relations, and family and sexuality) with astonishing inventive prowess. That development is manifested above all in Oceania’s range of technological gadgets, Newspeak neologisms, and Party slogans and catchwords.

And that is why Nineteen Eighty-Four is a gripping “novel”. That is, moreover, why it not only became a runaway bestseller in the early Cold War era, but also why it has exerted a cultural impact greater than any work of fiction in the 20th century.

John Rodden and John Rossi, “George Orwell Warned Us, But Was Anyone Listening?”, The American Conservative, 2019-10-02.

October 20, 2023

Orwell on “Boys’ Weeklies” (aka “penny dreadfuls”)

David Friedman is enjoying re-reading some of George Orwell’s collected essays and has some comments on one that I’m quite fond of as well — Orwell’s survey of “Boy’s weeklies” first published in Horizon March of 1940:

The Weeklies, of which Orwell identifies ten, produced by two different publishers and including two older series somewhat different from the others, were very popular reading, targeted at boys up to about fourteen or fifteen. All of the stories in the two older ones and many in the others were set in British public schools; Orwell suggests, plausibly enough, that much of the inspiration for the setting was Kipling’s Stalky and Company.

Orwell focuses mostly on the two older ones, each of which had a stock cast of characters and a setting that showed no sign of changing for the thirty years over which they had been coming out and recognizably stylized plots and dialog. He comments that although each claims to be written by a single named author — “Frank Richards” for one series and “Martin Clifford” for the other — it is obvious that a single author could not have done thirty years of weekly stories and that the stylized writing is in part a way of maintaining the illusion of a single author.

The essay is interesting both for the detailed, and to some extent sympathetic, description of the weeklies

In the Gem and Magnet there is a model for very nearly everybody. There is the normal athletic, high-spirited boy (Tom Merry, Jack Blake, Frank Nugent), a slightly rowdier version of this type (Bob Cherry), a more aristocratic version (Talbot, Manners), a quieter, more serious version (Harry Wharton), and a stolid, “bulldog” version (Johnny Bull). Then there is the reckless, dare-devil type of boy (Vernon-Smith), the definitely “clever”, studious boy (Mark Linley, Dick Penfold), and the eccentric boy who is not good at games but possesses some special talent (Skinner Wibley). And there is the scholarship-boy (Tom Redwing), an important figure in this class of story because he makes it possible for boys from very poor homes to project themselves into the public-school atmosphere. In addition there are Australian, Irish, Welsh, Manx, Yorkshire and Lancashire boys to play upon local patriotism. But the subtlety of characterization goes deeper than this. If one studies the correspondence columns one sees that there is probably no character in the Gem and Magnet whom some or other reader does not identify with, except the out-and-out comics, Coker, Billy Bunter, Fisher T. Fish (the money-grabbing American boy) and, of course, the masters.

and for Orwell’s analysis of their political implications. He thinks they are designed, probably deliberately by the owners of the firms that publish them, to indoctrinate boys with conservative views — respectful towards the upper classes, ignorantly patriotic, contemptuous of foreigners, blind to the real problems of British society.

Here is the stuff that is read somewhere between the ages of twelve and eighteen by a very large proportion, perhaps an actual majority, of English boys, including many who will never read anything else except newspapers; and along with it they are absorbing a set of beliefs which would be regarded as hopelessly out of date in the Central Office of the Conservative Party. All the better because it is done indirectly, there is being pumped into them the conviction that the major problems of our time do not exist, that there is nothing wrong with laissez-faire capitalism, that foreigners are un-important comics and that the British Empire is a sort of charity-concern which will last for ever. Considering who owns these papers, it is difficult to believe that this is un-intentional. Of the twelve papers I have been discussing (i.e. twelve including the Thriller and Detective Weekly) seven are the property of the Amalgamated Press, which is one of the biggest press-combines in the world and controls more than a hundred different papers. The Gem and Magnet, therefore, are closely linked up with the Daily Telegraph and the Financial Times. This in itself would be enough to rouse certain suspicions, even if it were not obvious that the stories in the boys’ weeklies are politically vetted. So it appears that if you feel the need of a fantasy-life in which you travel to Mars and fight lions bare-handed (and what boy doesn’t?), you can only have it by delivering yourself over, mentally, to people like Lord Camrose.

The essay ends with a somewhat tentative suggestion that someone ought to produce a left-wing equivalent and a discussion of some problems in doing so.

It is an interesting essay on its own merits. Still more interesting is the response, an article by Frank Richards rebutting Orwell and defending his own work. It turns out that, contrary to Orwell’s confident claim, most of thirty years of weekly stories by “Frank Richards” were produced by the same person, with occasional stories by other authors when he was for some reason not available. Further, as Orwell comments in a later footnote to his essay, Frank Richards was also Martin Clifford, so the same person produced, for thirty years, most of the contents of two different weekly magazines for boys.

His response shows him to be an intelligent and articulate writer. His views are conservative in a general sense; he makes it clear that the setting of the stories is an unchanging 1910 England because he does not think much of the changes since. But he also makes it clear that the reason his stories do not include strikes, unemployment, labor unions, and a variety of other features of the real world is that he believes that providing boys an imaginative foundation in a secure world helps equip them to face future difficulties in a world much less secure.

Of strikes, slumps, unemployment, etc., complains Mr Orwell, there is no mention. But are these really subjects for young people to meditate upon ? It is true that we live in an insecure world: but why should not youth feel as secure as possible? It is true that burglars break into houses: but what parent in his senses would tell a child that a masked face may look in at the nursery window ! A boy of fifteen or sixteen is on the threshold of life: and life is a tough proposition; but will he be better prepared for it by telling him how tough it may possibly be? I am sure that the reverse is the case. Gray — another obsolete poet, Mr Orwell! — tells us that sorrows never come too late, and happiness too swiftly flies. Let youth be happy, or as happy as possible. Happiness is the best preparation for misery, if misery must come. At least, the poor kid will have had something! He may, at twenty, be hunting for a job and not finding it — why should his fifteenth year be clouded by worrying about that in advance? He may, at thirty, get the sack — why tell him so at twelve? He may, at forty, be a wreck on Labour’s scrap-heap — but how will it benefit him to know that at fourteen? Even if making miserable children would make happy adults, it would not be justifiable. But the truth is that the adult will be all the more miserable if he was miserable as a child. Every day of happiness, illusory or otherwise — and most happiness is illusory — is so much to the good. It will help to give the boy confidence and hope. Frank Richards tells him that there are some splendid fellows in a world that is, after all, a decent sort of place. He likes to think himself like one of these fellows, and is happy in his daydreams. Mr Orwell would have him told that he is a shabby little blighter, his father an ill-used serf, his world a dirty, muddled, rotten sort of show. I don’t think it would be fair play to take his twopence for telling him that!

As a child in England in the early 1960s, I didn’t encounter any of the stories by Frank Richards (at least, I strongly doubt it), but many of the storylines and tropes of his work were still echoed by later authors, especially in the British comics (Lion, Tiger, Valiant, Rover, and The Hotspur among the many offerings). Alongside the heroic adventure stories, the war stories, science fiction, and the (omnipresent) football stories, there were still some that might well have been comic versions of Mr. Richards’ originals.

I missed them after we emigrated, but I was delighted find that the W.H. Smith bookshop at Sherway Gardens carried a few of them (at a significant mark-up, of course) so I was still getting my occasional comic fix until about 1974.

October 18, 2023

George Orwell’s views on Rudyard Kipling’s worldview

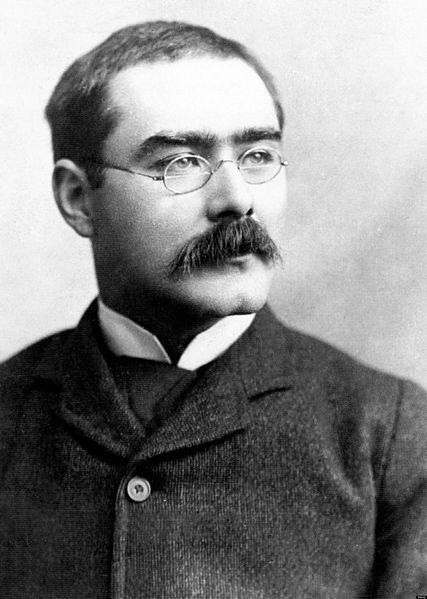

David Friedman comments on Orwell’s essay “Rudyard Kipling“, published a few years after the poet’s death in Horizon, September 1941:

Portrait of Rudyard Kipling from the biography Rudyard Kipling by John Palmer, 1895.

Photo via Wikimedia Commons.

During five literary generations every enlightened person has despised him, and at the end of that time nine-tenths of those enlightened persons are forgotten and Kipling is in some sense still there.

Orwell’s essay on Rudyard Kipling in the Letters and Essays is both more favorable and more perceptive than one would expect of a discussion of Kipling by a British left-wing intellectual c. 1940. Orwell recognizes Kipling’s intelligence and his talent as a writer, pointing out how often people, including people who loath Kipling, use his phrases, sometimes without knowing their source. And Orwell argues, I think correctly, that Kipling not only was not a fascist but was further from a fascist than almost any of Orwell’s contemporaries, left or right, since he believed that there were things that mattered beyond power, that pride comes before a fall, that there is a fundamental mistake in

heathen heart that puts her trust

In reeking tube and iron shard,

All valiant dust that builds on dust,

And guarding, calls not Thee to guard,But while there is a good deal of truth in Orwell’s discussion of Kipling it is mistaken in two different ways, one having to do with Kipling’s view of the world, one with his art.

Orwell writes:

It is no use claiming, for instance, that when Kipling describes a British soldier beating a ‘nigger’ with a cleaning rod in order to get money out of him, he is acting merely as a reporter and does not necessarily approve what he describes. There is not the slightest sign anywhere in Kipling’s work that he disapproves of that kind of conduct — on the contrary, there is a definite strain of sadism in him, over and above the brutality which a writer of that type has to have.

There are passages in Kipling, not “Loot“, the poem Orwell quotes but bits of Stalky and Company, which support the charge of a “strain of sadism”. But the central element which Orwell is misreading is not sadism but realism. Soldiers loot when given the opportunity and there is no point to pretending they don’t. School boys beat each other up. Schoolmasters puff up their own importance by abusing their authority to ridicule the boys they are supposed to be teaching. Life is not fair. And Kipling’s attitude, I think made quite clear in Stalky and Company, is that complaining about it is not only a waste of time but a confession of weakness. You should shut up and deal with it instead.

A more important error in Orwell’s essay is his underestimate of Kipling as an artist, both poet and short story writer. Responding to Elliot’s claim that Kipling wrote verse rather than poetry, Orwell claims that Kipling was actually a good bad poet:

What (Elliot) does not say, and what I think one ought to start by saying in any discussion of Kipling, is that most of Kipling’s verse is so horribly vulgar that it gives one the same sensation as one gets from watching a third-rate music-hall performer recite ‘The Pigtail of Wu Fang Fu’ with the purple limelight on his face, AND yet there is much of it that is capable of giving pleasure to people who know what poetry means. At his worst, and also his most vital, in poems like ‘Gunga Din’ or ‘Danny Deever’, Kipling is almost a shameful pleasure, like the taste for cheap sweets that some people secretly carry into middle life. But even with his best passages one has the same sense of being seduced by something spurious, and yet unquestionably seduced.

I am left with the suspicion that Orwell is basing his opinion almost entirely on Kipling’s best known poems, such as the two he cites here, both written when he was 24. He was a popular writer, hence his best known pieces are those most accessible to a wide range of readers. He did indeed use his very considerable talents to tell stories and to make simple and compelling arguments, but that is not all he did. There is no way to objectively prove that Kipling wrote quite a lot of good poetry and neither Orwell nor Elliot, unfortunately, is still alive to prove it to, but I can at least offer a few examples …

October 13, 2023

QotD: Sales of George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four

Nineteen Eighty-Four remains widely read today — and ubiquitously quoted and cited. In fact, during the spring of 2017, in the wake of the inauguration of President Donald Trump — and controversies about the “alternative facts” that his aides marshaled as evidence of record attendance figures at the event — the book achieved the remarkable, unprecedented feat of skyrocketing to number one on fiction bestseller lists. This occurred an astonishing 67 years after its original date of release. Nothing of this kind had ever happened to another book in publishing history. And, in the case of Nineteen Eighty-Four, it was the fourth time that it had topped the bestseller lists: first in 1954, in the U.K., after a BBC-TV adaptation sent sales soaring; second, throughout the English-speaking world during the so-called countdown to 1984 between October 1983 and April 1984; and third, in 2003, as the centennial commemorations of Orwell’s birth dominated the headlines and airwaves on both sides of the Atlantic.

In fact, it is fair to say that Nineteen Eighty-Four has never not been a bestseller and a publishing phenomenon. According to the website Ranker.com, the work has sold more than 25 million copies since 1949. More than a half century later, Manchester Guardian readers voted Nineteen Eighty-Four the most influential book of the 20th century. Waterstone’s, a British bookstore chain, has ranked Orwell’s dystopia as the second most popular book of the 20th century (behind J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings). That is an amazing feat in its own right, given that most people understandably do not particularly enjoy reading (let alone rereading) nightmarish stories of torture, betrayal, and brainwashing. The book’s ascent to the top of fiction bestseller lists in 2016 and 2017, along with the ceaseless invocation of Orwell’s catchwords to characterize the Trump administration, induced Signet, Orwell’s American publisher, to rush out a new print run of 500,000 copies. Expectations are that total sales will pass 30 million by the time of the 2020 election in the United States.

John Rodden and John Rossi, “George Orwell Warned Us, But Was Anyone Listening?”, The American Conservative, 2019-10-02.

October 8, 2023

Richard Blair’s memories of his father, George Orwell

Jonathon Van Maren contacted Richard Horatio Blair, the adopted son of George Orwell to discuss his memories of his famous father:

“My story starts on the 14th of May, 1944, when I was adopted by Eric Arthur Blair and his wife Eileen,” he told me. “This was during the Second World War. He’d been wanting a child for several years because he felt, rightly or wrongly, that he was unable to have children himself. I think this was compounded slightly by the fact that Eileen — my mother — was not very well herself, and in fact when I was ten months old, in March of 1945, she went to the hospital in Newcastle, which was the area where she was born and had gone to school. She went into a nursing home and died very soon after being anesthetized to have a hysterectomy. She probably had cancer, was very anemic, and simply had a heart attack on the operating table and died.”

The adoption had come about when Eileen was told by her sister-in-law, Dr. Gwen Shaughnessy, that she knew of a pregnant woman whose husband was off fighting. Orwell and Eileen adopted Richard when he was only three weeks old, and Orwell ensured that he alone would be known as Richard’s father by burning the names of the birth parents from the birth certificate with a cigarette. Richard would never know Eileen, as she died a mere nine months after the adoption took place, leaving the little boy and Orwell to fend for themselves. Some of Orwell’s friends suggested that perhaps he turn Richard over to someone else, but Orwell was having none of it. “I’ve got my son now, I’m not going to give him over,” Blair recalled. Blair even remembers Orwell “changing my nappy and feeding me after my mother died.”

“Meanwhile, my father had been asked to go to Germany at the end of the war by his friend, a gentleman by the name of David Astor of the Astor family,” Blair told me.

He was the proprietor of a newspaper called The Observer, and he asked my father — they had met during the war and become friends — to go to Germany after the war to observe what was happening, and it was while he was in Paris that he got a telegram telling him that Eileen, my mother, had died. He had to rush back and attend to the funeral and funeral arrangements. He decided the best thing he could do would be to go back to Germany and continue his war report, so that’s what he did. I was placed in the hands of relatives and friends to be looked after. I was cared for from that period onward by a nanny.

In 1946, he had decided to give up his reviews and extra work, because by now he had published his first major book, Animal Farm, which gave him enough resources to think about what to do next. And he had in his mind by then that he wanted to write what turned out to be 1984, and he decided to take the invitation of his friend David Astor to go to a remote island off the west coast of Scotland called Jura. He went up for a holiday and spent a couple of weeks there in the early part of 1946, came back, and announced that he would like to move out of London to this island of Jura and rent a farmhouse called Barnhill. A few weeks later I joined him with my nanny at the farmhouse, a place he had indicated to a friend was a very ‘un-get-at-able’ place.

Indeed it was. To reach the remote Hebridean island from London, “you had to take a train and several ferries, and then a taxi from the top part of the island, and then for the last five miles you had to walk,” Blair recalled. At first, it was Richard, Orwell, and his nanny, Susie Watson. This didn’t last long: Watson clashed with Orwell’s younger sister Avril and returned to London. “From that point on,” Blair told me, “I was cared for by my father’s sister Avril, and that continued well past when he died in 1950.” In the meantime, Blair still had a few precious years with his ailing father, who was trying to balance his fear of passing on his tuberculosis to his son with wanting to be an involved father. “He was really hands-on in a way that was really unusual for that era,” Blair told one interviewer.

In fact, he was so hands-on that he even worried about Richard’s television consumption, which is perhaps not surprising from someone who was so concerned about how people absorbed information — but Richard was, at this point, a very small child. “As a father he was completely devoted to me,” Blair told me. “He was terribly worried about my emotional development simply because he had TV, and he was very concerned that the views [on TV] might be passed on to me.” Blair still bears a scar on his temple from balancing on a chair while “watching him make a wooden toy for me”. He fell off the chair, cracked his head, and was bustled down to the village for a few stitches in the enormous gash on his forehead. “There’s a groove in the bone,” he ruefully told one interviewer. But there were no tests in those days, and so his head was sewn shut and he was sent back home again.

August 17, 2023

QotD: The decline of the British aristocracy

Probably the battle of Waterloo was won on the playing-fields of Eton, but the opening battles of all subsequent wars have been lost there. One of the dominant facts in English life during the past three quarters of a century has been the decay of ability in the ruling class.

In the years between 1920 and 1940 it was happening with the speed of a chemical reaction. Yet at the moment of writing it is still possible to speak of a ruling class. Like the knife which has had two new blades and three new handles, the upper fringe of English society is still almost what it was in the mid-nineteenth century. After 1832 the old landowning aristocracy steadily lost power, but instead of disappearing or becoming a fossil they simply intermarried with the merchants, manufacturers and financiers who had replaced them, and soon turned them into accurate copies of themselves. The wealthy ship-owner or cotton-miller set up for himself an alibi as a country gentleman, while his sons learned the right mannerisms at public schools which had been designed for just that purpose. England was ruled by an aristocracy constantly recruited from parvenus. And considering what energy the self-made men possessed, and considering that they were buying their way into a class which at any rate had a tradition of public service, one might have expected that able rulers could be produced in some such way.

And yet somehow the ruling class decayed, lost its ability, its daring, finally even its ruthlessness, until a time came when stuffed shirts like Eden or Halifax could stand out as men of exceptional talent. As for Baldwin, one could not even dignify him with the name of stuffed shirt. He was simply a hole in the air. The mishandling of England’s domestic problems during the nineteen-twenties had been bad enough, but British foreign policy between 1931 and 1939 is one of the wonders of the world. Why? What had happened? What was it that at every decisive moment made every British statesman do the wrong thing with so unerring an instinct?

The underlying fact was that the whole position of the monied class had long ceased to be justifiable. There they sat, at the centre of a vast empire and a world-wide financial network, drawing interest and profits and spending them – on what? It was fair to say that life within the British Empire was in many ways better than life outside it. Still, the Empire was underdeveloped, India slept in the Middle Ages, the Dominions lay empty, with foreigners jealously barred out, and even England was full of slums and unemployment. Only half a million people, the people in the country houses, definitely benefited from the existing system. Moreover, the tendency of small businesses to merge together into large ones robbed more and more of the monied class of their function and turned them into mere owners, their work being done for them by salaried managers and technicians. For long past there had been in England an entirely functionless class, living on money that was invested they hardly knew where, the “idle rich”, the people whose photographs you can look at in the Tatler and the Bystander, always supposing that you want to. The existence of these people was by any standard unjustifiable. They were simply parasites, less useful to society than his fleas are to a dog.

George Orwell, “The Lion And The Unicorn: Socialism and the English Genius”, 1941-02-19.

July 8, 2023

QotD: The amputation of the soul

Reading Mr Malcolm Muggeridge’s brilliant and depressing book, The Thirties, I thought of a rather cruel trick I once played on a wasp. He was sucking jam on my plate, and I cut him in half. He paid no attention, merely went on with his meal, while a tiny stream of jam trickled out of his severed œsophagus. Only when he tried to fly away did he grasp the dreadful thing that had happened to him. It is the same with modern man. The thing that has been cut away is his soul, and there was a period — twenty years, perhaps — during which he did not notice it.

It was absolutely necessary that the soul should be cut away. Religious belief, in the form in which we had known it, had to be abandoned. By the nineteenth century it was already in essence a lie, a semi-conscious device for keeping the rich rich and the poor poor. The poor were to be contented with their poverty, because it would all be made up to them in the world beyound the grave, usually pictured as something mid-way between Kew Gardens and a jeweller’s shop. Ten thousand a year for me, two pounds a week for you, but we are all the children of God. And through the whole fabric of capitalist society there ran a similar lie, which it was absolutely necessary to rip out.

Consequently there was a long period during which nearly every thinking man was in some sense a rebel, and usually a quite irresponsible rebel. Literature was largely the literature of revolt or of disintegration. Gibbon, Voltaire, Rousseau, Shelley, Byron, Dickens, Stendhal, Samuel Butler, Ibsen, Zola, Flaubert, Shaw, Joyce — in one way or another they are all of them destroyers, wreckers, saboteurs. For two hundred years we had sawed and sawed and sawed at the branch we were sitting on. And in the end, much more suddenly than anyone had foreseen, our efforts were rewarded, and down we came. But unfortunately there had been a little mistake. The thing at the bottom was not a bed of roses after all, it was a cesspool full of barbed wire.

It is as though in the space of ten years we had slid back into the Stone Age. Human types supposedly extinct for centuries, the dancing dervish, the robber chieftain, the Grand Inquisitor, have suddenly reappeared, not as inmates of lunatic asylums, but as the masters of the world. Mechanization and a collective economy seemingly aren’t enough. By themselves they lead merely to the nightmare we are now enduring: endless war and endless underfeeding for the sake of war, slave populations toiling behind barbed wire, women dragged shrieking to the block, cork-lined cellars where the executioner blows your brains out from behind. So it appears that amputation of the soul isn’t just a simple surgical job, like having your appendix out. The wound has a tendency to go septic.

The gist of Mr Muggeridge’s book is contained in two texts from Ecclesiastes: “Vanity of vanities, saith the preacher; all is vanity” and “Fear God, and keep His comandments: for this is the whole duty of man”. It is a viewpoint that has gained a lot of ground lately, among people who would have laughed at it only a few years ago. We are living in a nightmare precisely because we have tried to set up an earthly paradise. We have believed in “progress”. Trusted to human leadership, rendered unto Caesar the things that are God’s — that approximately is the line of thought.

Unfortunately Mr Muggeridge shows no sign of believing in God himself. Or at least he seems to take it for granted that this belief is vanishing from the human mind. There is not much doubt that he is right there, and if one assumes that no sanction can ever be effective except the supernatural one, it is clear what follows. There is no wisdom except in the fear of God; but nobody fears God; there fore there is no wisdom. Man’s history reduces itself to the rise and fall of material civilizations, one Tower of Babal after another. In that case we can be pretty certain what is ahead of us. Wars and yet more wars, revolutions and counter-revolutions, Hitlers and super-Hitlers — and so downwards into abysses which are horrible to contemplate, though I rather suspect Mr Muggeridge of enjoying the prospect.

George Orwell, “Notes on the Way”, Time and Tide, 1940-03-30.

July 4, 2023

Shock! Horror! Apparently you can’t trust that Abraham Lincoln quote about not believing what you read on the internet!

As a long-time collector of quotations, I almost had to take to my fainting couch when it became clear that President Lincoln never said anything about the internet being a tissue of lies. My original quotations collection (webbed here, but no longer actively maintained) was not particularly well-policed in the sense of ensuring that the quotations were both accurate and properly attributed. This is because I began collecting them before the internet was a thing for most people. When I began the blog, I tried to ensure that anything I quoted could at least be traced back to the site I found it on (which isn’t a particularly rigorous chain of evidence, but at the least it ensured I couldn’t be accused of making shit up).

In James Delingpole’s article on this topic, I was sorry to find that the very first fake quote he listed is indeed one that I had included in my original collection:

Only the dead have seen the end of war – Plato

I became aware of this marvellous quotation – so wise, pithy and dark – on one of my frequent trips to the Imperial War Museum. It’s one of a series inscribed on the wall beside the ramp leading down to the World War I/trench section. Another of my favourites is attributed to Thucydides: “There were great numbers of young men who had never been in a war and were consequently far from unwilling to join in this one.”

The Plato quote is so good it has been used many times since, inter alia by General Douglas MacArthur in a speech at West Point in 1962, as an aphorism apparently oft-cited by grunts in the ‘Nam, and by Ridley Scott in Black Hawk Down. But the quote is fake. Or at least its attribution is.

In fact it derives not from the Classical Age but from the early 20th century. It was invented by the Madrid-born philosopher, poet and later Harvard professor George Santayana. He clearly had a gift for this sort of thing for he also coined another of those phrases which you’ve always thought was devised by someone much more famous: “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” Usually this is attributed, in various forms, to Edmund Burke or Winston Churchill. But the former didn’t say it and the latter – as I suspect he quite often did – plagiarised it.

Fake quotes, whether genuine sayings that have been misattributed or fabrications which have been lent authenticity by putting them in the mouths of someone famous, have been a bugbear of mine for a while. I can probably date this to the time someone called me out on my favourite George Orwell quote: “In times of universal deceit, truth-telling becomes a revolutionary act”.

Annoyingly, I had used it a good half dozen times in articles and in internet chats before I learned that Orwell had never said it. I felt cheated and also foolish: surely as an English literature graduate I ought to have known such a thing, in the way that film buffs know that Ingrid Bergman never said “Play it again, Sam”.

But these are easy mistakes to make now that fake quotes are everywhere. Probably, this has always been the case but they have definitely proliferated with the advent of the internet, the shortening of attention spans (which make us more susceptible to gnomic verities that appear to sum everything up and obviate the need for further thought) and the corresponding appetite for meme-friendly aphorisms.

Many of these fake quotes, I’ve noticed, are printed over photographs or images of the alleged author. It’s a cheap trick but an effective one. No one ever is going to be fooled by a joke quote like: “Don’t believe everything you read on the internet. Abraham Lincoln, 1865.” But shove it on top of a picture of the 16th president with those familiar features – the wart, the chin beard, the lined skin and sunken eyes – and for a fraction of a second, the subconscious is taken in.

He finishes off the article thusly:

I’m reminded here, somewhat, of the introductory talk that Mark Crispin Miller used to give his students when he was still allowed by New York University to conduct his course on Propaganda. I paraphrase – you really should listen to this podcast interview for the full account – but essentially Miller warned his audience: “Be prepared to be very upset. You may be shocked to discover how many of the ideas you imagined to be your own are in fact the result of propaganda.”

It would definitely have come as a shock to the younger me. When you’ve had what you consider to be a superb education, steeped in classical literature, you tend to kid yourself that you are just too damn clever, too well-read, to fall for the kind of cheap confidence tricks that fool the unwashed masses.

Which, when you think about it, is what makes the faking of those classical quotes so cunning. They deviously exploit one of one of the cultural assumptions most deeply embedded in both the “educated” and “uneducated” classes alike: this idea that if one of the Ancient Greeks or Romans said it, it must be true because there’s almost nothing about the world that they didn’t know. Another thing they exploit is that the “educated” are rarely as clever as we pretend to be. For example, presented with a vaguely plausible quote with a fancy classical name attached, passing few of us are going to go: “Hang on a second. Did he really say that? Let me check …” Instead, we’ll go “Ah. The great Thucydides. He was the Greek general who wrote Anabasis. The sea! The sea!” and congratulate ourselves on what marvellously well-informed people we are.

Did you catch that palmed card there? Thucydides didn’t write Anabasis because he was far too busy writing the Commentarii de Bello Gallico!

June 14, 2023

“‘Misogyny’ is overtaking ‘fascist’ in the ‘I Don’t Own a Dictionary’ championships”

Christopher Gage suspects that George Orwell lived in vain:

In his essay, “Politics and the English Language”, George Orwell lamented the decline in the standards of his mother tongue.

For Orwell, all around him lay the evidence of decay. Orwell argued sloppy language came from and led to sloppy thinking:

A man may take to drink because he feels himself to be a failure, and then fail all the more completely because he drinks. It is rather the same thing that is happening to the English language […] It becomes ugly and inaccurate because our thoughts are foolish, but the slovenliness of our language makes it easier for us to have foolish thoughts.

With his effortless knack for saying in plain English the resonant and enduring, Orwell’s dictum is obvious as soon as uttered.

Orwell wrote that back in 1946. What would the author of Animal Farm and 1984 make of today’s standards?

“Misogyny” is overtaking “fascist” in the “I Don’t Own a Dictionary” championships.

Spend five minutes online, and you’ll encounter words defined in their starkest definitions. Words like “misogyny”, “misandry”, and “narcissist”, once possessed specific meanings. Now they mean whatever the speaker claims they mean.

The beauty of the English language lies in its precision. Sadly, those who populate the land which spawned the English language wield the language with all the grace and precision of a meat hook.

According to The Guardian, the recent Finnish election was suppurated with misogyny and fascism.

In that election, the one debased in misogyny and fascism, the losing incumbent Sanna Marin, a woman, won more seats in parliament than in 2019. The three candidates with the most votes — Riikka Purra, Sanna Marin and Elina Valtonen — were all women. Women lead seven of the nine parties returned to parliament — including the “far-right” Finns Party.

The Guardian didn’t permit reality to spoil a good headline.

As Orwell had it, “Fascism” is a hollow word. In the essay mentioned above, he said: “The word Fascism has now no meaning except in so far as it signifies ‘something not desirable’.” In modern parlance, the same applies to “misogyny”. “misandry”, “narcissism”, “gaslighting”, and just about every other buzzword shoehorned into a HuffPost headline.

June 10, 2023

QotD: The word “objectively”

For years past I have been an industrious collector of pamphlets, and a fairly steady reader of political literature of all kinds. […] When I look through my collection of pamphlets — Conservative, Communist, Catholic, Trotskyist, Pacifist, Anarchist or what-have-you — it seems to me that almost all of them have the same mental atmosphere, though the points of emphasis vary. Nobody is searching for the truth, everybody is putting forward a “case” with complete disregard for fairness or accuracy, and the most plainly obvious facts can be ignored by those who don’t want to see them. The same propaganda tricks are to be found almost everywhere. It would take many pages of this paper merely to classify them, but here I draw attention to one very widespread controversial habit — disregard of an opponent’s motives. The key-word here is “objectively”.

We are told that it is only people’s objective actions that matter, and their subjective feelings are of no importance. Thus pacifists, by obstructing the war effort, are “objectively” aiding the Nazis; and therefore the fact that they may be personally hostile to Fascism is irrelevant. I have been guilty of saying this myself more than once. The same argument is applied to Trotskyism. Trotskyists are often credited, at any rate by Communists, with being active and conscious agents of Hitler; but when you point out the many and obvious reasons why this is unlikely to be true, the “objectively” line of talk is brought forward again. To criticize the Soviet Union helps Hitler: therefore “Trotskyism is Fascism”. And when this has been established, the accusation of conscious treachery is usually repeated.

This is not only dishonest; it also carries a severe penalty with it. If you disregard people’s motives, it becomes much harder to foresee their actions. For there are occasions when even the most misguided person can see the results of what he is doing. Here is a crude but quite possible illustration. A pacifist is working in some job which gives him access to important military information, and is approached by a German secret agent. In those circumstances his subjective feelings do make a difference. If he is subjectively pro-Nazi he will sell his country, and if he isn’t, he won’t. And situations essentially similar though less dramatic are constantly arising.

In my opinion a few pacifists are inwardly pro-Nazi, and extremist left-wing parties will inevitably contain Fascist spies. The important thing is to discover which individuals are honest and which are not, and the usual blanket accusation merely makes this more difficult. The atmosphere of hatred in which controversy is conducted blinds people to considerations of this kind. To admit that an opponent might be both honest and intelligent is felt to be intolerable. It is more immediately satisfying to shout that he is a fool or a scoundrel, or both, than to find out what he is really like. It is this habit of mind, among other things, that has made political prediction in our time so remarkably unsuccessful.

George Orwell, “As I Please”, Tribune, 1944-12-08.

May 28, 2023

QotD: Karl Marx and the “excess labour” problem

In short: If you want to know what kind of society you’re going to have, look at labor mobility.

This is not to say that slavery is the only answer. There are lots of ways to absorb excess labor. Ever gone shopping in the Third World? There’s one guy who greets you at the door. Another guy follows you around the store, helpfully suggesting items to buy. A third guy rings up your purchases, which are packed up by a fourth guy, and a fifth guy carries them out (or arranges delivery by a sixth guy). And none of those guys are actually the shopkeeper. They’re all his cousins and whatnot, fresh from the sticks, and all of them are working four jobs with four other uncles at different places in the city.

Nor is it just a Third World thing. Basic College Girls love that Downton Abbey show, so I’d use that to illustrate the point if BCGs were capable of comprehending metaphors. George Orwell wrote eloquently about growing up on the very ragged edge of “respectability” at the turn of the century. He knew all about servants, he said, and the elaborate codes of conduct in dealing with them, even though his family could afford only one part-time helper. Your real toffs, of course, had battalions of servants to do every conceivable job for them. What else is that, old bean, but an elegant solution to labor oversupply?

Note also, since I’m giving you very basic Marxist history here, that we’ve just discovered the foundations of Feminism. Though Karl Marx was — of course — a total asshole to both his wife and his domestic help (of course he had “help”; the tradition of using and abusing servants while bemoaning the plight of the proletariat comes straight from the Master himself), he realized that his theories had a hard time accounting for the very real economic effects of domestic labor. Hence Engels’s The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State, which proves that even lemon-faced termagants with three degrees and six cats pulling down $100K per year shrieking about Feminism are MOPEs. You can cut the labor supply in half by shackling single gals to the Kinder, Küche, Kirche treadmill.

Severian, “Excess Labor”, Rotten Chestnuts<, 2020-07-28.